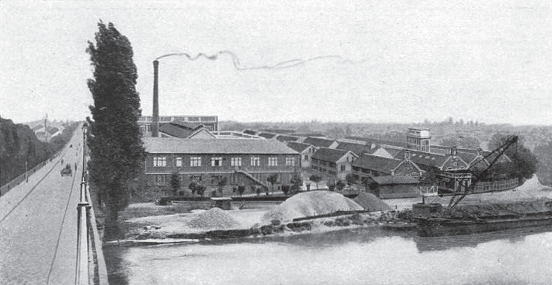

IN EARLY 1923, critic Louis Delluc traveled to northeast Paris to tour the studios at Gaumont’s Cité Elgé (fig. 4.1).1 Writing in the Magasin Pittoresque, he emphasized the modernity and fortitude of what he described as a “véritable cité . . . a great factory, [composed] of buildings made of brick, glass, and metal.”2 Delluc’s description must have been welcome news for an industry struggling to find its footing in the face of Hollywood’s postwar ascendance. Indeed, his visit may have been prompted by the mounting praise for Allan Dwan’s Robin Hood (United Artists, 1922), the spectacular sets of which dazzled critics and filled the pages of advertisements and press releases in French film journals. In his own review of the film, Delluc underscored the importance of these sets—which he compared to those in Cecil B. DeMille’s Joan the Woman (1916) and D. W. Griffith’s Intolerance (1916)—while also emphasizing Dwan’s skillful incorporation of their “splendor” into the film’s larger “rhythm.”3

Published on the two pages preceding his review, Delluc’s report about Gaumont reads as a kind of preemptive consolation—an effort to assure readers that Hollywood was not the only place with facilities like the Pickfair studios where Dwan re-created Nottingham. Marveling at the studio’s size and remarkable efficiency, Delluc holds up the Cité Elgé as an emblem of France’s filmmaking infrastructure and grounds for optimism about the industry’s future. He illustrates the studio’s plenitude by leading readers on a virtual tour of everything from supply closets and electrically lit stages to projection rooms and processing facilities, which he describes as “a great factory in the factory-center of cinema [une grande usine dans la cité-usine de cinéma].” For Delluc, these features made the Cité Elgé nothing less than an equal of “les studios américains d’Hollywood.”4 With such a grand “ville-cinéma,” he implies, how could France possibly fail to regain its once dominant position in the global film trade?

Delluc had reason to be confident. In the decade before the disruption caused by World War I, Gaumont’s Cité had become one of the largest and most active film sites in the world. When measured not solely by film receipts but also its output of machines, patents, and publicity materials, few companies could rival Gaumont’s productivity. While others had their stages and processing rooms, only the largest studios—including Gaumont’s Paris neighbor, Pathé Frères—could match the Cité Elgé’s manufacturing capacity, printing facilities, research labs, design workshops, and artists’ studios. The prewar strength of Paris’s film titans was built, in no small part, on the considerable infrastructural resources of these “studio cities” and their factory centers.

Delluc’s 1923 account well describes the achievements of the studio designers and architects who, in the previous two decades, had shaped Gaumont and Pathé’s studio expansion. In the early years of the French film industry’s postwar struggle against Hollywood, these buildings offered visible evidence of the industrial development that many, like Delluc, hoped might still put the brakes on the American invasion. The studios represented the outward manifestation of the industry’s capitalization and systematization from around 1903 to 1912. During this period, as historian Georges Sadoul argued, cinema broke free from its artisanal roots to become a huge industry.5 But what, precisely, did becoming an industry involve? What allowed companies like Gaumont and Pathé to trade artisanal practices for industrial ones? And how did those changes fit in the broader industrialization of Paris that had already been in the works for half a century (and was still shaping urban infrastructure)?

This chapter answers such questions by examining the processes and products of French cinema’s early industrial growth. It focuses on the too often overlooked buildings that supported industry expansion, the new technologies they produced, and the films and filmmaking practices they engendered. Studio modernization involved an array of operations and facilities that grew up around—and went well beyond—the filming completed in studios’ often-remarked-upon production stages. At large companies these included power stations to support studio lighting and factory machines; factory floors for manufacturing both film apparatuses and non-film devices; facilities for processing and storing film stock; ateliers where artists churned out painted backdrops, set pieces, and broadsheet poster art; printing workshops for catalogs, journals, and advertisements; and storehouses that stocked vast collections of sets, costumes, and props. The spatial proximity of these diverse activities contributed not only to the emergence of efficient production practices but also to the invention of new machines and techniques for pre- and postproduction work in new studio factories. As the studios became large centers of film production and manufacturing that looked and operated like industrial complexes, film companies adopted the same policies and practices—such as economies of scale and vertical integration—that guided other French industries.

Studio expansion and diversification paralleled the growth seen in New York at Edison, Biograph, and especially Vitagraph. But while Paris was marked by the introduction of similar new technologies, building materials, and infrastructural systems, their implementation and the regulatory frameworks that governed their early use had distinct and important consequences for the film industry. Like New York, Paris was shaped by a mix of creation and destruction. The renovation project known as Haussmannization that began in the 1850s continued to transform the city well into the twentieth century. Thanks, in part, to growing private real estate speculation and new zoning ordinances, Haussmann’s legacy included the expansion of private industry on the city’s outskirts, where new factories encircled the periphery. It also included the introduction of new municipal infrastructure, especially the Métro system (first opened in 1900) and the city’s first electrical grid (implemented from 1888).6

As in Manhattan, these infrastructural developments helped engender modern forms of movement, light, entertainment, and consumption. While others have examined how such hallmarks of modernity and modern life created a favorable context for cinema’s emergence and early development, this chapter emphasizes the material consequences of their inverse qualities: the chaotic, inconsistent side of industrial modernity that threatened to interrupt the film industry’s efforts to systematize and rationalize its production methods and helped pushed those efforts in new directions.7 From the inconsistent implementation of the electrical system to the risks and regulations associated with new industrial materials such as celluloid, this chapter highlights how Paris and its film industry struggled, at times, to cope with modernity’s underbelly, or what historian of technology Peter Soppelsa has termed its “fragility.”8

Traces of Paris’s “fragile” modernity could be found in the physical makeup and practices of the large studio centers—those cités du cinéma—where smokestacks betrayed the early and literal iteration of studio “dream factory systems.” Gaumont’s Cité Elgé and Pathé’s facilities in Vincennes and Joinville, on Paris’s southeastern periphery, became emblematic sites of the tangible links between cinematic, architectural, and technological development that marked silent cinema.9 From the electrical stations needed to provide power for buildings left unserved by the city’s fledgling electrical networks to the experimental machines designed in studio labs to interface with its unstandardized nodes and the storage depots mandated for safely housing celluloid film stock, cinema’s industrialized studios took shape according to their city’s evolving form.

That form left its mark no less on the films produced on the studios’ ever-larger stages. If, as Giuliana Bruno has argued, the first filmmakers made cinema “an art form of the street, an agent in the building of city views,” they often did so by rebuilding those streets on studio sets.10 Shifting our focus from film historians’ attention to cinema’s relationship to the urban environment in actualities, city symphonies, and location shooting, this chapter continues the last chapter’s focus on other significant ways that early filmmakers interacted with and physically affected urban space through both films and studios.11 From their new studio headquarters, Gaumont’s and Pathé’s film units continued in the tradition of the Lumière operators and other early filmmakers who found ready film subjects in the metropolis. Unlike their predecessors, however, directors such as Alice Guy and Louis Feuillade for Gaumont and Ferdinand Zecca for Pathé also followed Méliès’s model, rejecting the contingencies of modern urban life in favor of safely staged interiors.

The first studios had offered a retreat from gawking crowds and meddling authorities, creating a new version of city filmmaking—just off the trottoir—that existed alongside street actualities in the early 1900s. As film companies grew, both physically and financially, and strove to broaden their markets by making “art” films targeted at the bourgeoisie, they continued to use subjects culled from beyond the studio gates. Series such as Gaumont’s “Scènes de la vie telle qu’elle est” (“Scenes from life as it is”), for instance, made modernity’s inconsistency and fragility regular features of the silent screen. But such films did not involve an extensive turn to shooting on location in the city itself. Rather, they tended to use only fragments of city imagery to reproduce the city “as it was,” relying upon studio-constructed realism to tell stories about life behind closed doors.

This emphasis on the city’s interior spaces is hardly surprising given the utility of studio filmmaking made possible by the efficiently organized, systematized filmmaking centers that Gaumont and Pathé had put in place by 1910. To historians looking back at them with Hollywood in mind, these cités du cinéma bear all the trappings of the “dream factory system” that would emerge in Southern California only a few years later. But these similarities should not overshadow the numerous other industrial activities that took form within studio walls and facilitated French cinema’s modernization. Put another way, early cinema’s real factories were no less important to the industry’s development and success than the “dream factories” next door. To be sure, the industry’s economic triumphs in the early 1900s made cinema’s prewar expansion possible, but that tells us only so much about what economic success meant. By considering the infrastructure that subtended and developed thanks to those profits, this chapter demonstrates the studio’s critical role in shaping the techniques, machines, and practices that propelled the industry into and through the First World War.

INFRASTRUCTURE, INDUSTRY, AND THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF EARLY FRENCH CINEMA

For all of cinema’s importance as product and producer of modern urban life—from the Grand Café to the grands boulevards—like most French industries at the fin-de-siècle, early film manufacturing was more of a suburban affair. Méliès’s films had to travel six miles from his studio in Montreuil-sous-bois to reach their first screenings at the Théâtre Robert-Houdin. The competing companies that came and went in cinema’s first two decades littered the Parisian periphery with studios in places like Neuilly-sur-Seine (two miles west of the Champs Elysées), Boulogne-sur-Seine (three miles southwest of the Eiffel Tower), Courbevoie (two miles northwest of Paris’s western periphery), Epinay-sur-Seine (six miles north of the city’s northern edge), and Gentilly (just outside the city to the south). Pathé made its initial home a few miles south of Méliès’s in Vincennes, and even Gaumont, the closest of the group, laid the groundwork for the eventual Cité Elgé on the far side of the Parc des Buttes Chaumont on Paris’s northeastern edge, two and a half miles from the grand boulevards, the heart of redesigned Paris.

A remarkable 1902 painting by Pathé set designer Henri Ménessier offers one image of what the early days of film production looked like in these Parisian border zones (fig. 4.2). Set in Vincennes—Pathé’s first home and still its primary headquarters in 1902—the painting provides a rare behind-the-scenes glimpse of a film shoot: four actors in period costume perform in front of a wooden shed, goaded on by a gesturing director flanked by his cloaked camera operator. Alongside the shoot, three costumed actors wait for the next scene while an assistant stacks props and set pieces against the shed. Of greater interest than the filming itself is the striking image of the suburban context that would condition Pathé’s development over the next decade. Beyond the small garden and open fields immediately surrounding the stage, a nearby factory and distant smokestacks foretell the company’s (and French cinema’s) not-so-distant future. Read from foreground to background, the image offers a brief history of early filmmaking in Paris, from nearly rural production under cloudy skies to suburban industrial cinema in studio factories.

The painting neatly illustrates the broader context of suburban industrial development in which French cinema emerged.12 From Ménessier’s vantage point—perched above and five years removed from Pathé’s origins—the conspicuous traces of industrial modernity on the horizon betray the painter’s canny awareness that cinema’s own artisanal days were soon to end. While images of nature, as art historian T. J. Clark argues, had previously offered painters like Monet one last refuge of consistency in the immediate environs of a city being reconstructed in the image of capital, Ménessier’s view of Paris’s border landscape seems to suggest that nature’s “presence and unity” would have to be sought elsewhere.13 In contrast to the way that Monet could, in paintings such as Le Voilier au Petit-Gennevilliers (1874), include images of industry that “hardly register as different from signs of nature or recreation [such that] a chimney is not so different from a tree or a mast,” in Ménessier’s painting industry looms large as the silhouette seen just beyond the stage performers and, just to the right, in the clear form of a nearby factory.

While Ménessier’s single painting hardly represents a general approach to representing nature and technology, one is nonetheless left with the sense that it captures something important about the interrelationship between Paris, cinema, and capital. Ménessier’s horizon forms a horizon of expectation that links the late-nineteenth-century remaking of Paris in the image of capital with cinema’s own remaking—beginning precisely at the moment of the painting’s production—to fit the rational demands of capitalization. It also begins to suggest cinema’s increasingly important role in remaking Paris in capital’s more literal image—torn from reality, framed, and reshaped in 24 frames per second. If the medium of painting was proper to nature, as Clark argues—that painting was “like landscape, like the look of sky and water en plein air”—cinema, Ménessier’s prise de vues en plein air, was soon to become more like the city—like the look of the skyline and the ordered spaces beneath it.

That ordering would appear in the massive studios and studio factories that took form according to and in the image of the industrial developments that Ménessier’s painting juxtaposes with Pathé’s first staged productions. But more than simply the context for French cinema’s early development, industrialization played a significant role in shaping the industry’s growth. Money bound the two together. Gaumont and Pathé built their film businesses using large capital investments from industrialists who hoped either to shift their investments from older industries such as textiles manufacturing or to build on concurrent profits in new industries, especially electricity. Film’s first investors used their expertise in other industries to influence cinema’s strategic planning and define cinema’s own industrialization. And those other industries formed the backbone of the modernizing Parisian infrastructure to which film’s industrializing studios and new technologies would be forced to conform.14

In 1897, the Pathés incorporated their cinema and phonograph businesses with investors in the Compagnie Général des Phonographes, Cinématographes, et Appareils de Précision (hereafter, Compagnie), a group that hoped to exploit the growing phonograph industry and take advantage of Pathé’s film camera patent.15 One principal Compagnie investor, Jean Neyret, a former paper mill director with links to the bank Crédit Lyonnais, had interests in the growing electrical, steel, and coal industries. He was president of firms including Aciéries et Forges de Firminy, a company specializing in railroad materials, and vice president of Houillères de Saint-Etienne, a mining company headquartered in Lyon. Another, Claude Agricole-Grivolas, had been involved in manufacturing machines for the electricity industry since 1875, including Les Etablissements Grivolas et Sage et Grillet, which built apparatuses for electrical stations, and the Compagnie française d’appareillage électrique.16 He had also recently acquired the Manufacture Française d’Appareils de Précision, a company directed by Victor Continsouza and Henri René Bünzli that maintained a factory in Chatou, one of Paris’s important industrial suburbs. The factory—where Pathé’s film cameras would soon roll off the same assembly lines used to produce a variety of other precision machines—represents a concrete example of the importance that broader industrial developments had for cinema’s own industrialization. Pathé needed factories like Continsouza’s to mass produce its film equipment, much as it would soon need the city’s emerging electrical and transport systems—the infrastructures built by and/or using the materials produced by companies owned by the likes of Neyret and Grivolas—to produce and supply its machines and films.17

Gaumont developed according to similar circumstances. Company founder Léon Gaumont built the business by focusing on photographic instruments with funding from scientists and engineers interested in optics. He began his career as an assistant in the workshop of Jules Carpentier, the technician and inventor who built the first Lumière Cinématographe, and at Max Richard’s Comptoir général de photographie. In 1892 Gaumont bought Richard out using capital from Gustave Eiffel (who was interested in experimental optical devices) and Joseph Vallot (head of an observatory at Mont-Blanc).18 In 1895 he renamed the company the Société Léon Gaumont et Cie. The following year, with more funding from Eiffel, he initiated the Société’s first step toward industrialization by building a large machine workshop on a plot of land owned by his wife on Paris’s northeastern periphery, just adjacent to the Parc des Buttes Chaumont.

With the new workshop in place, Gaumont focused on designing and manufacturing precision photographic instruments such as lenses, binoculars, and photographic cameras to support the existing photography market. Meanwhile, he worked with Georges Demenÿ to develop what would become the company’s film camera. In the summer of 1896 the workshop produced the company’s first film projector, Demenÿ’s Chrono. The following year its products also included Demenÿ’s camera, the Chronophotographe.19 Gaumont promoted his new devices by producing films to go with them. He organized a small film production unit that, from May 1897, devoted its efforts to filming actualities in Paris in the fashion of the Lumière operators and Méliès, who had yet to complete his first studio.

Over five years later, Gaumont followed Pathé’s lead in modernizing and expanding both his filmmaking and manufacturing facilities. To do so, he needed a new injection of capital. He opted to incorporate the company and cede leadership to a new president, an industry magnate named Pierre Azaria. Like Neyret and Grivolas at Pathé, Azaria brought the company into contact with France’s booming electricity business. Alongside his duties as Gaumont’s president, Azaria served as president of the Compagnie générale d’électricité and was the supervisor for Continental Edison and General Electric’s French affiliates.20 Azaria’s interindustry duties would be mirrored in the research labs and on the factory floors that soon defined Gaumont’s studio compound.

These repeated links between cinema and the electrical industry signal more than simply the emergence of the tangled political economies that continue to underpin global cinema today. Rather, they represent only one aspect of an intertwined history that significantly affected film’s infrastructural and formal developments. For Pathé, the specific patterns of industrial development that shaped Paris’s eastern suburbs would help condition the company’s infrastructural foundation. Meanwhile, the creation of Paris’s electrical networks would help condition Gaumont’s continuing emphasis on technology by framing cinema within a context that necessitated technological intervention beyond the invention of cameras, projectors, and other film-specific machines. In each case, although rationalization and efficiency remained the prevailing ideals of cinema’s industrialization, the inconsistency of Paris’s modernization and its consequent inefficiency helped determine the form of rationality that Pathé and Gaumont’s respective industrial developments would take.

FROM ARTISAN TO INDUSTRY: EARLY INDUSTRIALIZATION AT PATHÉ

How, from its early years shooting on an exterior stage like the one painted by Ménessier, did Pathé become a massive company with studios and factories spread across Paris’s southeastern periphery? What guided its development from artisanal production to the economies of scale that made cinema akin to other modern industries? Pathé’s development and rise to industry dominance should be attributed in no small part to the industrial experience of its investors.21 Indeed, although Charles Pathé played a significant role in the Compagnie’s cinema business, his eager demands for expansion and repeated calls for new studio space often failed to win the support of the Board.22

Instead, under the watchful eye of its cautious backers, Pathé’s industrialization and investment in physical infrastructure advanced slowly, especially for the film business. In 1898, with one million francs of capital, the company built a single factory in Chatou for producing phonographs and added another only in 1899 when capital reached two million francs.23 On the strength of the phonograph profits, it also bought the Vincennes café that housed Charles’s film productions that same year. Here, they continued to make films en plein air (and possibly in a glass-enclosed room), turning out prints, according to Pathé, at a rate of forty kilometers per day by 1901.24 In 1902, recognizing the rapid expansion of the cinema market and bolstered by the booming phonograph business, Neyret, Grivolas, and new board member Albert Ivatts approved a series of projects to expand Pathé’s cinema production units.25

These initial projects focused on expanding production space and sheltering Pathé’s filmmakers, much as Méliès had done five years earlier. During late summer and early fall of 1902, Charles Pathé and Albert Ivatts oversaw the construction of a glass-and-iron-roofed “hangar” near the company’s courtyard production stage. Perhaps due to its initially cautious and frugal approach to infrastructural development, as well as the small scale of this initial studio, the Compagnie did not hire an industrial architect for the project.26 Instead, the directors elected to engage a series of Vincennes-based contractors to build the new studio, located at 43, rue du Bois.27

The structure offered Pathé director Ferdinand Zecca many of the same advantages already seen in Méliès and R. W. Paul’s similar glass-enclosed studios. In this new glass house, Zecca produced films that helped make techniques such as matte inserts and dissolving transitions common industry practices.28 The studio’s increased film output also contributed to the industry’s growth. At the Compagnie, cinema profits rose by 32 percent from 1902 to 1903, approaching the formerly dominant phonograph figures.29

Despite this success, Pathé and Zecca quickly found the studio lacking, first in light quality, then in size. While historians have tended to date the introduction of electrical lighting in French studios to 1903 or later, the minutes from the Compagnie’s Board of Directors meetings suggest that Pathé outfitted its first studio with electrical lights in 1902 after deeming its natural lighting insufficient.30 In November, Pathé sent word to the Board that the studio’s cost had risen by 14,000 francs in order to augment the power available for stage lighting. His report noted: “the current lighting, which is sufficient for small scenes with few actors, is not sufficient for large scenes with many actors on stage.”31 To complement the studio’s natural lighting, Pathé added enough power for ten arc lamps that were used with reflectors to redirect light toward the stage in order to create softer, more diffuse illumination. The results, he reported, put the company “in an exceptional position, allowing us rapidly to produce new cinema projects.”32

Soon, however, it became clear that the studio still lacked sufficient facilities to support the industry’s growing demand for films. Pathé sought greater efficiency, and he moved to modernize the company’s artisanal methods by transforming its physical spaces. Although he would continue to use the former café on the rue du Polygone as a workshop for processing film and producing machines, sets, and props, by December Pathé called for a new atelier devoted to set design. After visiting the existing workshop, the Board authorized up to 5,000 francs to build a glass-enclosed hangar on a rented property next to the studio. When negotiations with the neighboring owner fell through, the Board elected to follow a new proposal from Pathé, who suggested adding a glass roof to the rue du Polygone building at a cost of 20,000 francs.33

The new project, completed by late February 1903, allowed Pathé to take several important steps toward rationalizing its film output. First and foremost, the new facilities increased production of positive film stock to twelve thousand meters per day.34 Second, the new architectural space offers evidence of Pathé and Zecca’s growing attention to the importance of specialized workspaces and the division of labor among increasingly specialized workers. As Stéphanie Salmon describes, “The project [to build a set design atelier] reveals the need to multiply the spaces to assure the efficiency of tasks as well as the augmentation of numbers.”35 As would be the case for Alice Guy’s productions at Gaumont and for Méliès’s studio films, such changes helped attract set designers from Paris’s theater community.36 Their insertion into film production helped solidify the industry’s connection to the French theater, even as the expansion and modernization of film studios contributed to these professionals’ further incorporation into the film community and away from their stage work.

Despite the increased efficiency initially generated by its new workspaces, by early 1904 the new studio and design atelier proved, once again, insufficient for the Compagnie’s production needs. The lack of sufficient workspace produced new forms of inefficiency and waste. Pathé reported to the Board that the set design workshop was running at full capacity but limited storage meant that any décors not used for multiple films (a practice often necessitated by the demand for rapid production) had to be destroyed after each shoot. To make matters worse, several property owners surrounding the production studio had built new large buildings that blocked sunlight and thereby shortened the available working hours. Pathé proposed to solve these problems in one fell swoop by demolishing the existing studio in favor of a new, larger building to house set design workshops, storage facilities, and production stages. The new building would be high enough to avoid shadows from neighboring structures, and Pathé also reached an agreement with the proposed studio’s neighbors to restrict the height of their buildings.37 At the same time, he began plans for another facility in nearby Montreuil that would help maintain production during the construction in Vincennes.

EXPANSION AND DISPERSAL: THE “PROVISIONAL STUDIO” IN MONTREUIL

Pathé’s decision to build the studio in Montreuil rather than closer to the Compagnie’s current production facilities on the rue du Bois previewed the future dispersal of its facilities across Paris’s southeastern suburbs. Montreuil was a sensible location for this initial expansion: the provisional satellite studio would remain close to Vincennes, and Montreuil’s patterns of industrialization were favorable for a filmmaking facility. Owing to resistance from its agricultural producers, the community had industrialized slowly and on a small scale. As a result, small factories and ateliers greatly outnumbered the heavy industries seen northwest of Paris in places like Chatou, and as horticulture gave way to manufacturing, small agricultural plots increasingly became available for industry.38 Pathé thus faced little risk of seeing its studio overshadowed by a large, smoke-spewing factory or, given the small size of the adjacent plots, the kinds of neighboring construction projects that necessitated a new studio in Vincennes.

In early 1904, as preparations for the new Vincennes studio slowly progressed, the Compagnie purchased a lot at 52, rue du Sergent-Bobillot in Montreuil, only a stone’s throw from Méliès’s studio. Here, Pathé initially proposed a 3,000-franc “glass-and-iron hangar for equestrian and other exterior films.”39 Pathé later altered the plans, calling instead for a large glass house studio. Although often referred to by Pathé and others as the “provisional studio,” the resulting building continued to house film production through the 1920s and still stands on the same site today, making it the oldest remaining studio in France.40

A number of factors likely influenced Pathé’s decision to establish something more permanent in Montreuil. Most importantly, Pathé must have taken the rising demand for films as a signal (and perhaps a selling point for the previously cautious Board) to invest in future film production. Part of this investment would have gone into adding electrical lighting to studio infrastructure. Here, Montreuil proved a good setting for industries of all sorts, for it had access to one of the city’s private electrical networks, by no means a given, even in 1904. It also benefited from access to Paris’s growing transport infrastructure. From 1899, Montreuil had housed a tramway station facilitating access to and from Paris.41 Finally, Montreuil had, since at least 1870, been home to significant celluloid production. These patterns in Paris’s broader industrialization made Montreuil an ideal setting in which to build a full-fledged studio.

At its completion, the studio’s main glass hall covered 22 × 12 meters and, much like Méliès’s original studio, initially housed both film production and set design in the same central hall (fig. 4.3).42 One of the few existing images of the studio’s interior offers a sense of the studio’s hybrid working conditions. Much as in the earliest studios, set design, construction, staging, and filmmaking in Montreuil often involved the same spaces and workers. While this image, like many others of the time, may have been produced for publicity, there should be little doubt that work in such studios involved the kinds of concurrent activities depicted. Three workers rig a backdrop of a city scene painted in depth, which sits alongside another, angled backdrop for an interior scene. Meanwhile, operators prepare three cameras for shooting, and stagehands, including a worker sawing a board in the foreground, arrange set pieces. Much like the system Zecca and Pathé had begun to institute in Vincennes, these tasks would increasingly be spatially divided in newer and larger studios.

Such would be the case for the new Vincennes studio, a project for which the Compagnie spared little expense. The three-story structure’s cost, not including painting and glass, would rise to 95,000 francs, plus another 11,500 for the heating system.43 The studio marked a notable step in the industrialization of the Compagnie’s film division: it would be a modern industrial space designed and built by an industry professional. Pathé entrusted the studio to Eugène Laubeuf, a Chatou-based architect whose firm, Les Etablissements Laubeuf, had completed projects for companies including the Chemin de fer de l’ouest.44 This turn to professional architects—taken at approximately the same moment by the New York–based companies discussed in chapter 3—marks a decisive shift in which film companies made schematized spaces the basis for increasingly systematized production methods.

Laubeuf’s design for Pathé makes such systematization clear. Materially, it resembled French factory architecture of the day, with brick walls and windows on the rear and one side, while the remainder, including the roof, was glazed in iron-and-glass. Its layout points both to the division of tasks that had come to define the industry’s working practices and to the ways that architectural demands shaped the organization of those tasks.

Read from the ground up and back down, the three-story structure defined a circular film production process that moved from the arrival of workers and materials to set design, film shooting, and the departure of completed films. The ground floor consisted of four rooms plus a concierge’s office. In two ateliers—one for woodwork, the other for iron—workers processed raw materials into the backings and prototypes for sets and props. An adjacent closet provided storage space for these materials and previously used sets. This floor also housed the film developing laboratory, the placement of which was likely guided not only by the efficiency of being able to send completed films out the door, but also because it would allow workers to escape and fire fighters to enter in the case of an accident.

On the floor above, the set design workshop stood at the midpoint between the raw wood and metal that arrived at the studio door and the artificial worlds assembled on the stages above. Here, the set and prop materials built and stored below took final form alongside the formation of ideas for films. Spatially, the set designers needed to be on an upper floor to ensure sufficient lighting, a fact that would push later studio designers to include design ateliers on the topmost floors, providing access to the same light available for shooting. Alongside the workshop, the floor housed offices for the filmmakers and the studio director as well as Charles Pathé’s office, where he held regular meetings with set designers and filmmakers.45

Finally, the top floor, with its glass roof, let sunlight in and sheltered production. A system of black and white shades allowed Pathé’s directors to control the brightness and diffusion of light to the stage, just as Méliès had done in his first studio.46 The production space was divided in two, with stages on either side to allow for simultaneous productions. A specialty stage-building company, Wessbecher, designed the two stages, the larger of which included a subsection and trapdoors for trick effects, much like Méliès’s studio after its enlargement in 1899.47

In addition to promoting production efficiency, the new studios in Montreuil and Vincennes created new aesthetic possibilities.48 As Noël Burch has noted, their increased size, in particular, led Zecca and Pathé’s other directors to explore increasing camera movement in studio films. Shot against the large painted backdrops that came out of the new set design studios, the horizontal panning sequences that distinguish films such as Au pays noir (1905) demonstrate the films’ new degrees of dynamism.49 As with Méliès, the shift to new glass-and-iron studios brought increasing spatial fluidity—including not only these horizontal and vertical pans but also spatial tricks such as appearing and disappearing objects, multiple exposures in the same frame, and the movement of characters and objects across the frame.

These features helped Pathé’s popular films dominate the French and American markets, leading to unprecedented growth that necessitated further infrastructural expansion to keep up with demand.50 Before Pathé could extend its operations in Vincennes, however, its growth took an unexpected turn in the face of Paris’s fragile modernization. In the wake of a scandal caused by a celluloid-related fire, new laws governing film storage drove the creation of Pathé’s next cinema “city” in the nearby Parisian suburb of Joinville-le-Pont. This shift would change the geographic face of film production and mark French studio cinema for years to come.

“L’AFFAIRE DES FILMS” AND EXPANSION TO JOINVILLE

Just as Laubeuf was putting the finishing touches on the new Vincennes studio in September 1904 and Pathé began to look ahead to further infrastructural development, the cinema industry came under unexpected new pressure from municipal authorities. On Saturday, February 20, 1904, an explosion at a celluloid comb manufacturing workshop in central Paris left fourteen workers dead and numerous others injured. The resulting attention to celluloid storage created what Pathé’s Board of Directors referred to as “l’affaire des films” (the film affair). As the company sought to expand its growing film production and manufacturing units, it faced the suddenly difficult task of finding an acceptable location for its facilities.

The celluloid exploded early one afternoon, just after workers returned from lunch. The workshop was located in a multiuse building at the corner of the boulevard de Sébastopol and the rue Etienne-Marcel, a densely populated area in the center of Paris. Onlookers described a horrifying scene. As the fire grew, workers and residents on the upper floors leapt to escape the flames. Descriptions of the “catastrophe” filled the popular press, and in the following days many Parisians gathered outside the Paris morgue, hoping to catch a glimpse of the victims, who were not, much to the crowd’s dismay, put on display.51 News of the disaster continued to occupy the press for more than a week as investigators sought the origins of the explosion and families mourned the victims. The investigation revealed that the fire most likely came as the result of a misplaced cigarette that ignited a stockpile of celluloid.52

City officials responded to the tragedy by reinforcing existing laws regulating the storage and use of hazardous materials in the city limits. For the cinema industry, the new policies brought celluloid production, processing, and storage facilities under county regulations as “dangerous, unhealthy or uncomfortable establishments [établissements dangereux, insalubres ou incommodes].”53 Surprisingly, despite the often-described attention to the dangers of film fires in theaters after the Bazar de la Charité disaster of 1897, spaces of film production and storage had remained largely out of regulatory view. Pathé’s Board of Directors was thus surprised to receive word in September that the company’s positive film stock would be reclassified to conform to the new code. To meet the limitations on celluloid storage, the Board initially intended simply to spread its supply across a series of small rented locations.54 Two months later, however, the matter remained unresolved.

At first, Pathé divided its stock between four storage sites in order to conform to the new code. It allocated 300 kilos to the studio on the rue du Bois, 1,200 to its nearby processing facilities on the rue du Polygone, 800 to another neighboring site on the rue des Vignerons, and 300 more to the company’s headquarters on the rue St. Augustin. City inspectors, however, rejected the rue du Polygone facility (where Pathé stored its original film prints), despite the fact, Pathé noted, that it was built “below ground, with iron cabinets that could be easily flooded, and that the film strips were themselves in iron boxes, sheltered from any exterior contact.”55 The following month, inspectors also rejected the rue des Vignerons storage site, leaving Pathé in dire need of new facilities.56

By January the company was becoming desperate. Even if it were able to convince municipal authorities to allow the maximum storage rates at the company headquarters, the Montreuil studio, and the rue du Polygone facilities, it would still run short by more than 3,000 kilograms per day. To make up for the lack of storage space, Pathé resorted to an inconvenient and inefficient system of moving celluloid from facility to facility throughout the day.57

These restrictions threatened to slow the company’s stunning growth. In February 1905, Pathé reported that the Vincennes factory, which was already producing 8,000 meters of film per day, could not meet the potential market demand. Eager to reduce its reliance on film imports from George Eastman, the Compagnie also sought new facilities for producing its own film stock.58 While the best course of action would be to enlarge the Vincennes factory, the “film affair” left the company little choice but to retreat to a more remote location. Perforating negative film and processing, developing, printing, and storing positive prints would thus be divided from storing negative film stock and producing films, which would continue at the Vincennes and Montreuil studios. This planned division of the production process anticipated the company’s later decision to divest its production arm and instead rent out its production facilities and contract with smaller companies to produce films for distribution.59

The Board quickly approved the purchase of a new, two-acre site on the south bank of the river Marne in the neighboring community of Joinville-le-Pont.60 The site’s cost of 80,000 francs satisfied the Compagnie’s directors, who also noted that it offered important access to major roads and a railroad station that would facilitate film distribution.61 After several months of negotiations with the Municipal Council of Joinville and the Public Health and Safety Council of the Department of the Seine, Pathé received authorization in August 1905 to build a storage depot capable of holding up to 10,000 kilograms of celluloid and a series of workshops for celluloid production.62

The Public Health Council outlined four specific regulations for the new facilities that would put Pathé in accordance with departmental regulations. First, all celluloid had to be enclosed in metal boxes and placed in a storehouse built of noncombustible materials and surrounded by a masonry wall two meters from the building, all located at least thirty meters from the street and fifteen meters from the other factory buildings. Second, Pathé had to build an “intermediary depot” for the factory’s daily output, located in proximity to the workshops. Third, the workshops themselves had to be 20 × 12 meters in size, limited to a single ground level, and built entirely from noncombustible materials. Each had to be equipped with six emergency doors opening onto the exterior. The workshops’ steam heating systems had to have effective ventilation shafts, and all lighting had to be electrical, with switches and fuses placed on the building’s exterior. Finally, the individual workshops (each of which had to be limited to a single task) were required to be separated by alleys of at least 5 × 8 meters.63

As was the case with Edison’s studio in the Bronx and numerous other studios, the building codes designed to regulate modern urban development thus had an important effect on the organization of film production practices. Especially as studios became large industrial centers, they simply could not escape the notice of the city inspectors charged with governing urban modernization. In addition to these requirements, Joinville’s Municipal Council negotiated seven further stipulations that focused largely on the aesthetics and environmental effects of the new facility. The Council’s regulations required that Pathé design its factory to have “an elegant architectural silhouette,” avoid large chimneys, be encircled with gardens, have walls lined with trees, not emit dark or noxious smoke, and deposit waste water into a designated sewer. These provisions reflected the community’s reluctance to become part of the growing industrialization of Paris’s suburbs—to avoid, that is, the kind of factory encroachment displayed in Ménessier’s painting of the first Pathé studio.64

Pathé initially met these requirements. Much like Edison, who had hired Hugo Kafka to design the Bronx studio to ensure it would meet Manhattan’s building codes, Pathé entrusted the Joinville facilities to a similarly experienced architect. He hired a Vincennes-based architectural firm, Moisson et fils, led by Théodore-Léon Moisson, who specialized in hotels and rental properties, and his son, Georges, a recent graduate of the École des Beaux-Arts.65 The firm completed the first atelier in early December and work continued at a rapid pace. Despite its agreements with the Municipal Council, Pathé also eyed opportunities to expand. In April 1906, as the original construction neared completion, Pathé reported that the facilities were already four times larger than originally projected (and complained that it had again become necessary to add two more ateliers for developing and tinting films).66

A fawning article in Phono-Ciné-Gazette, a monthly industry magazine with ties to Pathé, celebrated the new factory’s grandiosity by taking readers on a behind-the-scenes tour of the five original ateliers, which housed, respectively: (1) machine supplies, projection rooms, shipping and handling offices, and tinting; (2) perforation, printing, developing, and drying; (3) film cleaning and the heating systems; (4) electricity, and (5) storage. Such articles contributed to the emerging identity of film studios by offering readers a journey into what it described as the “midst of the labyrinths of this city—for it is truly a city.”67

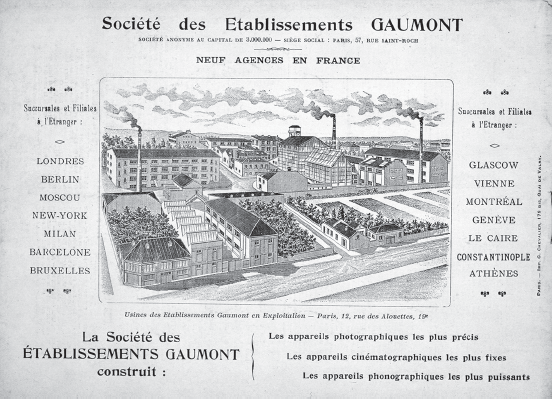

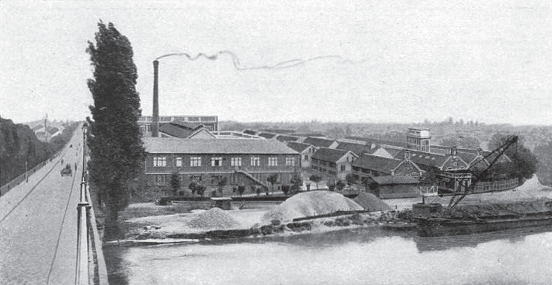

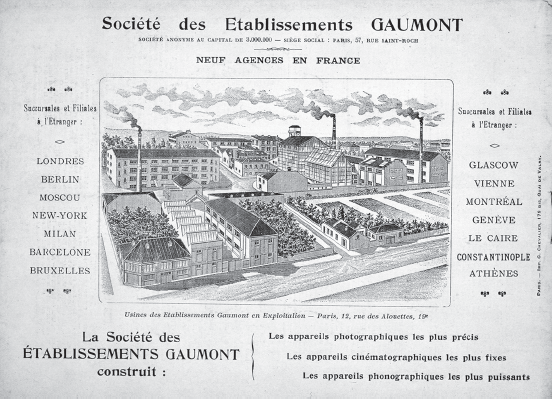

For the remainder of 1906 and into 1907, Pathé continued to press for further extensions of the new Joinville facilities, even as the existing construction dragged on. These efforts were complicated by Pathé’s other ongoing efforts, which included purchasing and enlarging a facility in the northeastern Parisian neighborhood of Belleville to manufacture cameras and projectors, building (and then enlarging) a new factory in Vincennes for coloring film prints, enlarging the film processing facilities in Vincennes, and, for the first time, expanding its operations to America.68 At the end of 1907, however, Pathé finally approached the Department of the Seine with a new proposal to expand its celluloid storage depot in Joinville to accommodate 30,000 kilograms of film stock. The Préfecture authorized construction of two new depots with capacities of 20,000 and 10,000 kilograms. The Compagnie hired a new architect, Charles Pathé’s Vincennes neighbor, Georges Malo, to build these depots as well as an additional series of ateliers and a large smokestack to serve its now enormous printing and processing factory (fig. 4.4).69

As images of the resulting facilities demonstrate, Pathé had far exceeded the original provisions of its agreement with Joinville and county authorities. Aside from the trees that line the near factory wall and the proper spacing that separates the line of ateliers to the right, the new construction blatantly ignored the original agreement, including its interdictions against multistory ateliers and, most obviously, large smokestacks and dark fumes. Although these flagrant violations infuriated the Municipal Council, the county ultimately dismissed the city’s complaints. Much to its chagrin, Joinville had become a city forever marked by the industrialization of cinema.70

Over the next two years, as it led the shift to renting rather than selling films, Pathé continued to expand operations in Joinville and especially in Vincennes. On the rue des Vignerons, the Compagnie further developed its printing and processing facilities while adding more studios. Two new glass-and-iron structures housed, respectively, the studios of the Société cinématographique des auteurs et gens de lettres (SCAGL) and Jean Comandon’s “studio scientifique.” The studios reflected Pathé’s new orientation toward subjects targeting middle-class audiences and its focus on renting studios and distributing affiliate companies’ films.71

A photograph of the rue des Vignerons with these additions reveals a sprawling complex that recedes almost beyond view. In Vincennes, as in Joinville, Pathé controlled a cité du cinéma carefully crafted for efficient production and distribution of the machines and films that powered French cinema and made Pathé its most dominant company. Such photographs represented film industry power as a form of spatial dominance created by studios and factories reaching out in every direction and poised to overtake what little remains of the surrounding landscape.

Pathé’s chief French competitor, Gaumont, would make such images of industrial strength the familiar iconography of its own studio “city,” the Cité Elgé. Like Pathé, Gaumont would produce a model of industrial rationalization, but it would focus its efforts on a single site on Paris’s northeastern periphery. Much as Pathé’s dispersed development took form according to Paris’s industrialization in the southeast and municipal regulation of industrial materials like celluloid, so Gaumont’s concentrated expansion was shaped by the vicissitudes of Paris’s modernization. In particular, Gaumont would face a problem that Pathé had largely managed to escape: finding a way to power its new studio city.

GAUMONT’S CITÉ ELGÉ AND THE INCONSISTENCY OF ELECTRICITY IN FIN-DE-SIÈCLE PARIS

The specifics of Gaumont’s early development have often been overshadowed both by scholars’ attention to Pathé and by the tendency to focus only on Gaumont’s central production studio, the largest in the world before World War I. While this studio was no doubt the most visually impressive of Gaumont’s facilities, the other buildings that formed the Cité Elgé offer a more complete image of French cinema’s industrial growth in the early 1900s. From its origins in photographic technology workshops, Gaumont grew into a company with diverse interests in technological research and development that overlapped and intertwined with its film productions. Those interests came, in no small part, from the necessities created by the company’s urban industrial context.

During its industrialization between 1897 and World War I, the Cité Elgé responded and played host to a number of important technological developments in cinema and in the broader processes of modernization that were transforming the city of Paris. In particular, the city’s emerging electrical infrastructure and its inconsistent form and patterns of development pushed Gaumont in directions that cannot be accounted for if the company is understood only as a film producer and its studio only as a single, if enormous, production stage. From its studio expansion plans to its research and product development strategies, the broad intermedial scope of technological and artistic production that Gaumont would foster during the 1910s and into the 1920s came as a direct result of the material and financial conditions created by the city’s turn-of-the-century infrastructural developments.

Cinema—and France’s first studios—would arrive in a city with radically uneven electrical infrastructure and little standardization. Gaumont recognized its need for machines such as electrical transformers to interface with new urban technologies. This need meant that even as Gaumont devoted more and more resources to film production, the company never shed its roots in technological research and development. The results of urban technological change ensured that at companies like Gaumont, film studio production remained closely aligned with film factory manufacturing.

That the electrical industry, in particular, came to play such a large role in early French cinema should come as no surprise. From as early as 1875, inventors and purveyors of electricity and electrical lighting had begun building an industry in France through the slow but steady process of illuminating cities and transforming industrial power. In Paris, electrical lighting became a viable and desirable alternative to gas systems first in major public spaces: department stores (the Magasin du Louvre and the Bon Marché), spaces of entertainment (the Hippodrome, the Opéra, and the Musée Grévin, each of which installed arc lights in 1878), as well as industrial spaces such as railroad stations and construction sites.72 The 1881 Exposition internationale d’électricité in Paris sparked new industry growth by facilitating an international exchange of ideas, technologies, and enthusiasm, especially for the public debut of Edison’s new carbon filament lamp.73 By the mid-1880s electrical lighting was becoming common in Parisian stores and theaters, and in 1886 the Municipal Council installed electric lights in its administrative headquarters—the Hôtel de Ville—and began considering plans for a municipal lighting system.74

The city met strong resistance from France’s gas industry, which managed to protract the transition to electricity—with much more success than its American and German counterparts—into the early twentieth century.75 The 1889 Exposition Universelle, however, went a long way toward convincing the Municipal Council to electrify the city. In addition to constructing buildings and monuments such as the Eiffel Tower, preparations for the Exposition included other efforts to modernize Paris’s physical appearance. Municipal authorities were particularly concerned with implementing public electrical installations, lest the Exposition, in historian Alain Beltran’s words, “show the whole world that the ‘City of Light’ scarcely merited its name.”76 Concurrent developments in the private sector underscored the value of transforming the city’s illuminating infrastructure.

A series of gas-related accidents at Parisian theaters led to both new city regulations and a more general shift by private owners to electric lighting. On May 27, 1887, a fire at the popular Opéra-Comique killed eighty-four performers and patrons and destroyed the theater. Investigators linked the fire to the theater’s gas lighting system, triggering widespread renovations of Parisian theater lighting.77 The media spectacle and government intervention that followed bear striking resemblance to the aftermath of the infamous film fire at the Bazar de la Charité ten years later, which killed 121 spectators, mostly wealthy noble women whose full skirts provided ready tinder.78 In response to the Opéra-Comique fire, commercial venues such as the Odéon, Olympia, and Moulin Rouge joined the Palais Royal, Nouveau Cirque, Musée Grevin, and Paris’s large hotels in installing new incandescent lighting systems.79

Thus even as the Municipal Council began debating plans for building the city’s electrical system in 1888, investors and developers had already started the slow process themselves. This existing infrastructure contributed to council debates that focused largely on whether the city’s electrical networks would be public or private. The city elected to implement a hybrid form consisting of one municipal system (with an electrical works serving the central markets at Les Halles and the surrounding neighborhoods) and six sectors granted to private suppliers for eighteen years (up to 1907).80 The introduction of these private electrical providers expanded the market for electrical machines as factories arose in and around the capital, creating ample profits for the electricity investors who later funded the young film industry. Such investments would be only one of the important effects that the city’s decision would have on early film development.

As the Municipal Council quickly recognized, the private system was rife with problems that limited its coverage and consistency, problems that would continue into the 1910s. The six private concessions offered widely varying degrees of service and used competing and often incompatible electrical technologies. Four of the six companies employed direct current systems, but only two of those four used compatible technologies.81 Moreover, much to the Municipal Council’s chagrin, the concessions showed little interest in expanding their networks beyond already inhabited areas and the sites of heavy consumption. And why would they? When the city made it clear in 1899 that it would not renew the concession system past 1907, there was no incentive to develop. In 1904, the city created a commission charged with finding a solution for centralizing electrical production, standardizing the city’s networks, and expanding service to areas with little to no electrical infrastructure.82 Still, by the end of the concession in 1907, northeastern Paris—home to the Cité Elgé—remained almost entirely unserved. The twentieth arrondissement did not possess even the most basic electrical network, and the network in the nineteenth remained untenably sparse.

The lack of network coverage in these areas left an indelible mark on Gaumont. In contrast to Pathé, which was served by the Compagnie Parisienne de l’air comprimé, Gaumont’s facilities remained stranded in an electrical no-man’s-land that would not receive municipal power until after World War I.83 Gaumont responded by mimicking the strategies used at other large industrial and commercial establishments with high levels of electrical consumption. These companies simply produced their own electricity. In 1889 the six concessions provided only about 30 percent of the city’s overall consumption from twelve electrical stations (versus twenty-four nonconcession stations), a figure that rose to only 54 percent in 1896.84 At large Parisian hotels, theaters, and stores such as the Bon Marché, in-house generators remained more practical than linking up with the city’s fledgling networks. The basements of sites such as the Opéra and the Grand Café—future site of the first Lumière screening—housed, in Beltran’s words, “veritable electrical factories.”85 These private generators at times served multiple buildings or small neighborhoods, creating “islands” of autonomous electrical production that remained legal throughout the concessionary period.86

Gaumont’s Cité Elgé would become one such electrical island. Not surprisingly, the studio would also become a site of experimentation in electrical technologies and a key node in the circulation of ideas and technologies that helped the growing film industry and its dispersed and shifting networks of distribution and exhibition interface with the city’s new electrical networks. The scientists and technicians charged with developing the technologies with which to do so also contributed to cinema’s industrialization by redesigning machines and processes from the earliest days of cinema. The Cité Elgé would thus house important industrial developments not only in its impressive studios, which represent the height of prewar cinema’s industrial rationalization, but also in the diverse workshops and manufacturing facilities that made the company much more than just a film concern. Indeed, for all of Louis Delluc’s rhetoric about studio production at the Cité Elgé in 1923, the studio’s postwar strength would ultimately rest as much on the capacity of its research labs and factory floors as its studio stages.

RATIONALIZATION AND INDUSTRIALIZATION AT THE CITÉ ELGÉ

From its first steps toward industrialization, Gaumont took form according to Paris’s infrastructural context. In 1904, the company began expanding the Cité Elgé from a single machine workshop and the partially enclosed stage on which Alice Guy had been producing films since 1898 by replacing the latter with the world’s largest film studio—a glass-and-iron cathedral more than six times the size of Méliès’s original studio in Montreuil. The structure marked a monumental step in the film industry’s growth, not simply for its size but also due to its efficient layout and modern equipment. In particular, the studio was designed to account for the Cité Elgé’s need for electricity, both for the studio’s lighting and heating systems as well as for the laboratories and workshops that quickly appeared around it. In short, the world’s largest film studio would also have to be a power plant.

Contemporary architecture critics did not overlook the studio’s importance. Even Les Nouvelles Annales de la Construction took a rare detour from its coverage of the development of the Parisian Métro system to devote an article to the studio, accompanied by a photo of the completed glass house (fig. 4.5).87 The journal’s March 1906 article highlights architect Auguste Bahrmann’s unique blend of building technologies and the technological systems needed to produce an appropriate climate for film production.

Like studio designers before him, Bahrmann’s principal concern remained maximizing the direction and quantity of light to accommodate filmmakers’ continuing reliance on daytime shooting for the majority of their productions. He positioned the two-story building on a north-south axis and aligned the main stage along the eastern side of the wider northern wing’s top floor. The studio’s thin iron skeleton permitted maximum natural sunlight to reach the stage from midday through the afternoon, and stair access to the ceiling allowed the possibility of suspending diffusing fabrics to distribute light more precisely. On the southern wing’s glass-covered top floor, Bahrmann created a large, well-lit atelier for set design.

The ground level’s layout focused on cinema’s need for darkness, especially in postproduction. Below the set design ateliers on the southern wing, the studio would support, in the Nouvelles Annales reporter’s words, “the greatest convenience of photographic manipulation.”88 Here, Bahrmann created a system of small dark rooms linked by hatches (guichets) for efficient movement of film through the successive stages of processing.

Alongside these processing facilities, the ground floor housed the studio’s electrical substation. A steam generator provided the electricity necessary to heat the large building and provide power for electrical lighting setups used, at least initially, only to accentuate natural illumination. The Nouvelles Annales article devotes particular attention to the heating system, a special air-circulating machine designed by Frédéric Fouché and exhibited two years earlier at the International Exposition in St. Louis. Fouché’s Aérocondenseur, which could heat the entire studio in around one and a half hours, underscores the importance of climate control in modern industrial spaces in general and film studios in particular.89

The article also underscores the systematization of the production process that the studio design facilitated. Bahrmann’s arrangement of the processing rooms to match the successive stages of postproduction might be expected, but he also designed the studio to enable efficient preproduction and shooting. His design promoted fluid access to the shooting stage to facilitate rapid scene changes. An empty space on the ground level below the stage provided temporary storage and space for staging sets, props, and performers between takes. Two adjacent stairwells connected the ground level and the dressing rooms adjoining the stage above. And a system of pulleys linking the two levels allowed set pieces to be quickly transported to and from the set. Set pieces could also be moved directly from the adjacent design atelier to the stage, then dropped immediately to the floor below for storage.

These pathways did not close off variations in filmmaking practice and film form, including a range of focal lengths, camera angles, and set arrangements. To supplement the possibilities created by the already large size of the stage, Bahrmann’s design used large wheeled partitions to allow the annex on the studio’s northern end to be used, alternately, as dressing rooms or to extend the stage. In this way, the design would help determine both the content and form of the studio’s films. As the Nouvelles Annales article noted, the variability of Bahrmann’s design would make it possible to stage “historical events” on a grand scale.90

With newly hired assistant Louis Feuillade, Alice Guy made just such a confluence of new film subjects and forms the studio’s product. Capitalizing on the new set design ateliers, Guy used larger, more elaborate backdrops to accentuate the stage’s expanded space. In films such as Le Statue (1905), Guy created seemingly boundless views that marked a striking departure from the comparatively enclosed spaces of her earlier studio films. In other cases, the films playfully revel in the studio’s lavish size, reflexively celebrating and exploring its expanded frame. In Clown, chien, ballon (1905), for instance, the addition of a plaza scene painted in depth creates the illusion of open exterior space for balloon-chasing chaos (fig. 4.6). The act’s canine performer and floating prop probe the boundaries of the new studio set, bounding from foreground to background, side to side, and to the backdrop’s highest reaches, prefiguring Albert Lamorisse’s exploration of Paris in Le Ballon rouge (1956).

The studio’s large size and set design facilities also allowed Guy to explore complex arrangements of sets, props, and characters. In films such as her celebrated 1906 version of the Passion Play, La Vie du Christ, she staged fluid movements of characters into and out of the frame through elaborate wooden sets with multiple levels and large openings painted to appear as stone arches. Her new complex staging stood in marked contrast to her pre-studio films, which feel claustrophobic by comparison. Using these new architectural arrangements, Guy still tended to focus on a single primary action in the center of the frame, but the increased space allowed for more action on the periphery, where the pantomimed gestures of early actors and actresses often give the films striking new degrees of dynamism.

In the new studio and under Guy’s tutelage, Feuillade also mastered this use of depth, a formal strategy that would later earn him accolades in the Fantômas and Les Vampires series. As David Bordwell has described, Feuillade used sophisticated approaches to staging characters and directing audience attention within the single-tableau format. These strategies responded in part to Gaumont’s later demands for rapid filmmaking, often on reused sets, but Feuillade first developed his multilayered staging techniques on the studio’s deep stage and its more architecturally sophisticated set pieces, as seen in films such as La possession de l’enfant (1909) and later in the “Scènes de la vie telle qu’elle est” series.91

In addition to these formal developments, the studio’s technological systems also facilitated other shifts in film technique. The electrical substation allowed Guy and Feuillade to control studio light more precisely by supplementing the sun with a growing repertoire of artificial lights. A behind-the-scenes film from 1905—Alice Guy tourne une phonoscène sur la théâtre de pose des Buttes-Chaumont—shows the new studio and its lights in action, with Guy directing one of the company’s early sound films. Two slow pans reveal large banks of lights to the left and right of the stage (set before the same painted backdrop that appeared in Le Statue). After signaling for the lights to be illuminated, Guy sets the Chronophotographe system in motion and begins the scene, a dance sequence featuring a troupe of performers equal to the stage’s grand size. The film highlights the sophistication of studio film production that Guy put in place within less than a year in the new studio. Using multiple banks of artificial lights aided by reflectors, Guy developed techniques for creating even lighting across the stage. Such measures were necessary to satisfy audiences who had grown accustomed to well-lit studio productions without the harsh shadows that came to mark films as poorly made and unrealistic.

For all of the transformations to film production that the studio enabled, its initial setup remained consistent with many norms for the period. In particular, the close proximity of pre- and postproduction in a single building continued the practice seen at smaller studios such as Méliès’s and Pathé’s studios in Montreuil. Although the new studio streamlined these activities by organizing adjacent work, storage, and improvisational spaces to allow for continuous shooting and rapid processing, soon the increasing demand for films encouraged Gaumont to expand the studio’s production capacity.

The company quickly began to surround the giant glass cathedral with workshops to support film production and its continuing production of machines. The Cité Elgé grew to include celluloid storage depots designed to meet municipal requirements for safe storage of film stock and prints for distribution, and adjoining buildings soon housed ateliers devoted to editing films and manufacturing small parts for cameras and projectors. By 1907, the studio had also grown to include workshops for tinting and painting films, laboratories for testing new coloring technologies, and additional facilities for perforating, developing, and printing film stock. Rising electrical usage in these new facilities also forced the company to add additional electrical generators.

In addition to facilities devoted to film production and postproduction, Gaumont made the Cité Elgé an important site for technical research and manufacturing. Encircling the main production studio, a campus of small factories and workshops included separate ateliers for work in metal, brass, and nickel; milling, metal turning, and smelting; and carpentry, cabinet making, and varnishing. These were supported by research and development facilities, including laboratories for research in optics, chemistry, and electricity. Gaumont filled its labs with scientists, especially chemists trained in photography, who came to play an important role at large film manufacturers. One such scientist, Léopold Lobel, a chemist who came to Pathé from the chemical corporation Bayer in 1905 and would go on to be technical director for Lux, later explained that for cinema to industrialize it had needed “a teacher [who was] ready to make it benefit from its science and experience.”92

These scientists worked with technicians to replace machines and techniques from film’s earliest days with new systems capable of supporting the industry’s growth. Most importantly, Gaumont’s laboratories produced automated processing and printing technologies—including continuous developing machines and systems for washing and drying film prints—necessary for the production and distribution of films on a mass scale.93 Gaumont also used these laboratories and workshops to continue developing and manufacturing its line of cameras and projectors.

Other innovations directly addressed problems related to Paris’s inconsistent modernization. Several focused on the dangers of celluloid. As they worked to develop safety stock, Gaumont’s scientists produced technologies designed to protect projectionists and spectators and meet municipal regulations. These included special boxes for safely transporting celluloid and protective housings for projectors. Gaumont’s engineers also developed devices such as electrical transformers to deal with the lack of a reliable municipal electrical grid. Its machines competed with those in development at Pathé as well as non-film companies such as Westinghouse.

As these activities suggest, filmmaking was only one piece of cinema’s capitalization and modernization, and studios came to house much more than just film production. The modernization of studio facilities nonetheless made these other technological developments possible. Modern studios provided laboratory space for their development and ready testing sites for new prototypes. And in the case of technologies such as new automatic film processing systems, they profited from the new precise regulation of light and temperature in the studio. In sum, the systematization of studio production, the industry’s technological development, and the industrialization of studio infrastructure all developed together.

As new technologies and techniques made celluloid preparation and film processing more efficient, Gaumont added further structures to support all phases of production. In 1908, the company added two large buildings alongside the original glass cathedral: one to house a large new set design department and a second to serve as a printing factory for publicity materials. The new buildings again reveal Bahrmann’s attention to how architectural design could contribute to rationalized efficiency. Bahrmann linked the new décor building with the existing studio, creating a direct passage between the stages, the large design shops, and the storage facilities (fig. 4.7). In addition to raising and lowering set pieces to the floor below the stage, assistants could now quickly move them from the adjacent building, which grew to house large collections of props and furniture. These storage houses again contributed to the films’ growing realism and expanded storytelling possibilities by putting an expanded repertoire of tools for visual world-building at the filmmaking team’s disposal. Any materials that could not be found in the prop storage rooms could be built or painted in the set design and construction shops housed in the new building beside the studio. Beneath a glass-and-iron rooftop, teams of painters, sculptors, and woodworkers fashioned the company’s film worlds in large-scale artists’ studios—the historical forebears of the film studio now brought into its purview.

The new printing facility that Bahrmann built alongside the set design building allowed Gaumont to accommodate industry changes brought about by film companies’ adoption of the new system of renting rather selling film prints to distributors. This shift in industry practice transferred the burden of producing publicity to the film manufacturers, who needed to create audiences for their films, both among exhibitors and audiences. From its artists’ studios and printing facilities, the Cité Elgé produced diverse forms of visual culture—especially its Feuilles de la Marguerite posters—that helped construct the meaning of Gaumont’s central film texts in ways that prefigure today’s “convergent” new media landscape.94

Supported by these new facilities, Gaumont’s filmmakers grew into a large production team. After Guy’s departure to America in 1907, Feuillade took over as studio director and was joined by Léonce Perret and a band of both well-known and now forgotten filmmakers including Roméo Bosetti, animator Émile Cohl, Étienne Arnaud, Gaston Revel, Henri Fescourt, Jacques Feyder, and numerous others who churned out Gaumont productions by the hundreds. In 1911 and 1912, Gaumont again expanded the studio’s shooting space, extending the existing glass house and connecting it to a new sound stage to support advancing sound-on-disc research and sound film productions. Here, Gaumont’s young filmmakers honed their formal techniques, working side-by-side in the midst of the studio’s ever-changing row of sets (fig. 4.8), which Bahrmann again connected directly to a new set design atelier and storage area.

By 1913, the Cité Elgé had grown into a campus of more than two dozen buildings. Publicity materials emphasized the company’s range of services, including the studio and sound film studio as well as the factories that produced film machines. Depictions of the Cité gracing Gaumont’s catalog covers offered potential buyers an image of industrial rationality, stability, and strength. Ordered rows of industrial buildings frame the central glass cathedral, while smokestacks like those dotting the horizon of Ménessier’s 1902 painting now dominate the smoky skyline (fig. 4.9). Such images gave visual form to the studio’s fundamental place in cinema’s industrialization and capitalization in the century’s first decade. Often flanked by financial figures made to match, they project a cinema remade in and defined by the image of capital. That image—built on the shifting infrastructure of a city that was, itself, being remade in capital’s image—must be understood in its direct relationship to the broader infrastructural context that helped determine its form.

Not surprisingly, the context that shaped the Cité Elgé’s growth would also become one focus of the studio’s film subjects. Municipal infrastructure and its inconsistencies produced favored cinematic tropes, whether shot on location or remade in the studio. In this way, much as, in T. J. Clark’s view, painting was like nature, so cinema would be like the city. Put another way, if, as Clark argues, “no other subject [than nature] . . . offered painting the right kind of resistance, the kind which had the medium seem more real the harder it was pressed in the service of illusion,” something similar might be said for cinema’s relationship to the city.95 Rebuilt on studio sets and combined with “real” footage shot in the streets, the Paris of Gaumont’s city cinema of the early 1910s helped make cinematic illusion the height of urban realism.

CINEMA, THE CITY, AND STUDIO-PRODUCED REALISM