Some day, no doubt, when Time shall have granted a past to the motion picture industry . . . a suitable tablet will be imbedded in a certain spot on the grounds of a certain studio in Edendale, a suburb of Los Angeles. The testimony of the tablet will be to this effect: “Here was Born the Great Photoplay Producing Industry of California, June, 1909.”

—Los Angeles Times (1916)1

BY THE 1910S, the relationship between the film studio and nature that had defined film production for almost two decades had come full circle. Dickson and Méliès had made an idealized climate—at once sheltered from and modeled upon the natural environment—the initial measure of studio success. The filmmakers who established the industry in California reversed the formula, making the studio archetype the standard against which natural settings would be judged. As one article put it, some producers thought of California itself as “a natural studio.”2 Their success would depend on both.

The tendency to evaluate natural settings according to studio ideals reflected the latter’s persistent importance for western filmmakers. Indeed, within only a few short years, they had re-created the studio’s architectural history, which could be found in physical form nestled between Southern California’s rolling hills. Between 1909, when the Selig Polyscope Company established Los Angeles’s first studio, and 1915, when Universal City opened a few miles north as the world’s largest, the region witnessed a curious reinvention of studio form. Following Selig’s lead, competitors dotted the Southern California landscape with open-air stages like those seen in cinema’s first half decade. Soon, companies such as Selig and Pathé, prompted by the same concerns about climate control that drove earlier filmmakers, enclosed their stages in glass. As investment in the region increased, glass-enclosed studios equipped with electrical lighting became de rigeur for California producers who could afford them. By 1914, no fewer than seventy companies had built or refurbished studios in the Los Angeles region, and their various forms would coexist there, often on the same properties, into the 1920s.

This massive investment in studio infrastructure would seem to contradict two of the most commonly assumed reasons for the film industry’s western migration—namely, California’s picturesque settings and dependable sunlight. Industry boosters touted the region as a filmmaking utopia of sunny days for winter-weary directors and seductively cinematic landscapes for audiences clamoring for realistic scenes. Film historians have tended to reproduce this rhetoric, in more guarded terms, in their broader accounts of early filmmaking there.3 But why, if the region’s fabled natural lighting was so desirable, did the same types of light-regulating glass and electrical alternatives to sunlight used back East so quickly reappear in the West? Moreover, if one of their principal goals was realism, why did filmmakers so readily reproduce the studio artifice they already knew so well (and that audiences had supposedly come to loathe)?

The answers to these questions lie, in part, in Southern California’s imperfect climate and the unrealistic expectations produced by local boosters and enthusiastic reporters who willfully ignored its at times cloudy reality. Indeed, faced with weeks of spring rain and periods in which morning clouds might obscure the sun into the afternoon, filmmakers relied upon studios for shelter and alternative shooting locations. Even on clear days, western studios allowed filmmakers to manipulate and regulate sunlight in order to produce ideal shooting conditions, much as they had learned back East. What’s more, the deceptive idea that one should, despite the region’s variable weather, be able to film there 365 days a year meant that studios became necessary to achieve companies’ goals for film output. In short, booster rhetoric and industry competition produced high expectations, and studios offered one way to meet them.4

More generally, by 1910 industry norms had made the studio an essential and assumed component of most companies’ models of film production and most filmmakers’ working practices. At a moment when audiences’ and exhibitors’ demands for film—spurred by the expansion of exhibition venues during the Nickelodeon boom—had created a growing market for their products, film corporations needed consistent, efficient output to assure reliable profits. Given the success of the industry leaders—especially Edison, Biograph, Vitagraph, and Pathé—that had made significant studio investments central to their businesses, the first companies in California had good reason to copy their chief competitors’ studio models.

This chapter reexamines cinema’s westward expansion as a history of the studio’s reproduction and the material, practical, and conceptual continuities between early studio history and the emergence of studio cinema in Southern California. While we tend to think of early western filmmaking in terms of location shoots and natural light, the studio was always close at hand, both as a physical site for all phases of production (from set construction to film processing) and as part of the conceptual framework for filmmaking practice, whether in the studio or beyond its walls. That framework rested on the studio-born assumption that film space could be created, manipulated, and transformed. Thus even when western-bound filmmakers traded studio sets for landscapes bathed in natural light, they continued to apply this idea of studio plasticity to non-studio settings.

Much as studio production had helped shape filmmakers’ approaches to city filming in the 1890s, so the persistence of studio norms influenced location shooting practices in the early 1910s. Indeed, this chapter will argue that the very idea of “location” that developed in the work and discourses of this period’s filmmakers, film companies, and industry observers was inextricably tied to studios and to the notions of space and spatial production developed in them. Building on the knowledge that a single studio stage could be adapted to fit a wide range of subjects, filmmakers conceptualized “location” as what I will term the “studio beyond the studio.” Put simply, just as they knew that with the right scenery, the film studio could appear to be any place in the world, so filmmakers hoped that, with enough land and the right props and backdrops, so could California.

The idea that the best location was an ideal studio would lead to the development of the most significant studio innovation of the “transitional era”: the studio backlot. As filming locations became more contested—at once more fervently desired by competing film units and more strictly controlled by their owners—film companies sought to ensure not simply access to locations but also control over them. They did so by buying up large swaths of land on which to build more and larger studio stages and to construct semipermanent location sets. On these backlots, filmmakers again confronted the persistent tension between their need, on the one hand, for sunlit, natural-looking scenes and, on the other, for technologically mediated working environments.

Unable to escape that tension, they concretized a tenuous but lasting solution: a flexible pro-filmic space comprised of interior studio stages lit by electrical lights, sun-lit backlots built on the principles of studio interiors, and “natural” locations that, like manufactured sets, could serve as repeated shooting sites. In the mid-1910s, that solution came to define the working environment of Southern California filmmaking, and it would characterize Hollywood production in the decade to come. Ultimately, the quests for light and authenticity that had driven filmmakers away from their studio homes led them right back to the studio and to a spatial model for filmmaking with an inescapable name: the “studio system.”

QUESTING FOR LIGHT, NATURE, AND AUTHENTICITY OUTSIDE THE STUDIO

The same search for light that shaped the initial development of film studio architecture from the Edison laboratory to the outskirts of Paris also drove cinema’s western expansion in the United States. As film historians have often described, in 1907 filmmakers in New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago began leaving their dark, cloudy homes during winter months in search of longer and brighter daylight hours. Made more easily accessible by the increasing mobility of the nation’s expanding railroads, warmer and sunnier locales from Florida and Texas to Colorado and California became alternative film production centers—veritable filmmaking “hotspots”—for several months of the year.

This seasonal migration signaled not so much filmmakers’ desire for alternatives to studio artifice as their recognition of that artifice’s periodic inadequacy. Despite the technological developments that had greatly improved studio lighting in the century’s first five years, filmmakers, exhibitors, and critics still preferred the look of films shot in natural light (see chapter 3). That, combined with the high cost of electricity, meant that few companies could rely exclusively on electrical lighting. The annual arrival of winter’s short, cloudy days and the resulting decline in productivity thus left filmmakers in need of better lighting conditions, whether naturally sourced or otherwise. Their search for bright sunlight went hand-in-hand with scientists’ simultaneous search for better ways of artificially reproducing it. Indeed, the two practices represented two sides of the same coin. Film companies demanded efficient solutions for mass-producing films, and, in the absence of cost-effective artificial means in the studio, they would simply manufacture their scenes elsewhere.

Filmmakers from Chicago led the way in exploring the possibility of off-season production. In the fall of 1907, the Selig Polyscope Company sent stage director Francis Boggs to Los Angeles, where he shot exterior scenes for Selig’s one-reel production of The Count of Monte Cristo (1908).5 The next summer, Gilbert M. Anderson (aka “Broncho Billy”) led a troupe from another Chicago company, Essanay, on a trip to Golden, Colorado, where he recruited cowboys and began producing what would come to be known as “westerns.”

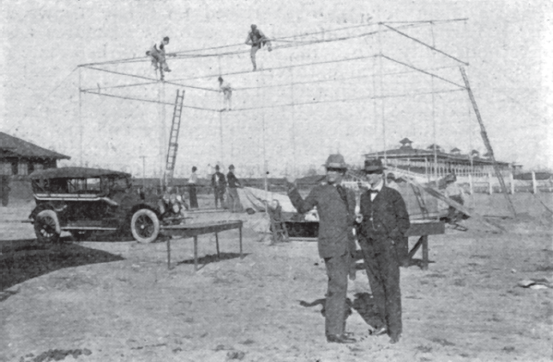

New York–based companies followed suit. The New York Motion Picture Company sent a unit to Los Angeles in late 1909. Soon Vitagraph, working from notes taken by owner Albert Smith during a vacation to Santa Barbara earlier in the year, announced its own plans to send a troupe across Nevada and Southern California that December. And in early 1910, D. W. Griffith’s Biograph company arrived in Los Angeles for the first of what would become an annual winter trip.6

At the same time, Chicago, Philadelphia, and other New York and New Jersey–based companies sought other suitable filming locations in the South. Florida, in particular, attracted so many film companies that it became, in one historian’s estimation, “the first Hollywood.”7 During the winter of 1908–1909, the studio-less Kalem company sent a first group of filmmakers to Florida. The crew set up shop in Jacksonville, which they chose, in large part, because the city was home to a large station serving the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad.8 Sigmund Lubin sent filmmakers along the same route from Philadelphia to Jacksonville the following year and later made it the home of Lubin’s comedy company. Selig filmmakers from Chicago also arrived in 1910, and between 1912 and 1914 a litany of companies including Essanay, Vitagraph, Edison, and Thanhouser spent at least brief periods in the Jacksonville area.9

Other companies took their operations to more far-flung locations. In 1910, Gaston Méliès, responding to the success of film companies in the West, moved from New York to San Antonio, Texas, to produce westerns. Méliès remained there until 1911, when he moved the company to Santa Paula, California, where it worked briefly before setting off on a filmmaking voyage to the South Pacific and East Asia.10 The IMP company, which included Mary Pickford and later the director Thomas Ince, went to Cuba in 1910, and filmmakers for the Yankee Film Company, Essanay, and Vitagraph ventured as far as Bermuda, Panama, Jamaica, and Mexico.11

Their willingness to go where the light required coincided with—and may have contributed to—calls for new film subjects. Jaded by the kinds of studio films that had filled screens during the Nickelodeon boom, at least some audiences and exhibitors demanded new subjects and settings. Taking advantage of their new locations, filmmakers produced new subjects that complemented the more common fare shot in studio interiors and city streets. Like earlier travelogues and fiction films shot on location, the resulting scenes elicited enthusiastic responses from audiences and critics, who reserved particular praise for their depictions of natural landscapes. As one 1911 review described, “It is this element of the big out-of-doors with its sweep and freedom, that makes Western subjects so attractive to the city shut-ins. Melodrama has no thrill to compare with the thrill of big old nature.”12 Such praise was common in contemporary criticism, which often compared these settings with what came to be seen as dull studio-produced interiors. As the same reviewer exclaimed, “How much finer is this than a narrow room with painted settings and Jack making love to Gladys on the sofa!”

Such criticisms of studio films suggest that these voyages out of the studio fulfilled more than simply a need for light or longer working hours. The primacy of mass-produced studio fictions had created a context in which something different from banal narratives and dull, repetitive visual aesthetics might find success. Nature scenes offered aesthetic alternatives to painted sets and provided an experience of nature for urban dwellers—the “city shut-ins”—who remained embedded within the artificial environments of the modern metropolis.

Audiences’ attraction to images of nature in motion was consistent with early responses to natural settings and similar views available in nonfiction films. One has only to think of Georges Méliès’s reported fascination at the sight of leaves fluttering in the wind in Louis Lumière’s Repas de bébé (1895)13 or spectators’ delight at such films as Rough Sea at Dover (Robert W. Paul, 1895) and its numerous remakes to grasp the early power of film’s technological reproductions of the natural environment.14 Early filmmakers traveled the globe to capture such scenes, which included the southern and western locales seen in such films as Royal Gorge (Edison, 1898), Old Faithful Geyser (Edison, 1901), and Devil’s Slide (Bitzer, Biograph, 1902).15 Even as film production became largely studio-based, these widely popular films of the natural environment—known variously as “nature studies,” “natural scenic films,” and, most commonly, “scenics”—remained an important component of travelogue and other nonfiction programs.16 Their “dream world[s] of cinematic geography,” as Jennifer Peterson rightly argues, “simulate[d] the real world in order to allow the spectator to leave [it].”17

This simulated escape from urban modernity helped attract eastern city dwellers to western film subjects. As Nana Verhoeff argues, early westerns succeeded, in part, by spicing up the scenery. To the travelogue’s vicarious form of travel, westerns simply added adventure, offering “nature as a thrilling and exotic site for escapism for the urban population.”18 As audiences warmed to these western settings, film companies sought to capitalize on their interest by increasing western and southern productions.

They also recognized the utility of producing versions of the West closer to home. During longer and brighter seasons, eastern producers took advantage of undeveloped local landscapes to produce “Easterns” (historical films set and produced in eastern locations) and “Eastern Westerns” (western subjects produced on eastern terrain).19 Whether produced in California, Colorado, or New York, westerns banked on the perceived authenticity of their natural locations.20 As an American Film Manufacturing Company advertisement proclaimed, these were “Real Western Pictures—Real Western Settings.”21

The success of Eastern Westerns came precisely, however, from viewers’ relative disregard for authenticity. As historians of the early western have argued, to urban dwellers the “western” landscape amounted, quite simply, to anything that was not the city.22 The success of simulations of the West attest to the fact that it wasn’t the western landscape per se that attracted audiences so much as any natural setting that could pass for it.23 Filmmakers met these desires by using film technology to bring the natural environment to the spectator’s doorstep—another version of the cinematic “enframing” by which studio filmmakers captured urban environments and international expositions.

Representations of nature, in other words, were no less technologically mediated than their studio-produced counterparts and were shaped by many of the same aesthetic and technological considerations. Indeed, even as they addressed their needs for light and authenticity by exiting their studios, filmmakers remained reliant upon studio norms, both for film style and filmmaking practice. The first westerns shot in New York and New Jersey beginning around 1907, for instance, worked consistently, in Scott Simmon’s words, to “reinforce the landscape’s theatricality.” Filmmakers used standard setups in which “the camera [was] generally fixed in place, actors’ bodies filmed full length, and each shot held for a relatively long duration.”24 While this style, as Simmon notes, often reproduced conventions developed in picturesque landscape paintings by the likes of Claude Lorraine—“natural theatrical spaces open to the light and usually framed on the sides by overhanging trees”—it also reproduced the basic strategy of the studio tableau.25 Much as they did in the studio, filmmakers relied on their ability to frame scenes quickly in suitable lighting conditions, a necessity that encouraged formal repetition and the emergence of standard conventions for recording nature. In short, tight shooting schedules privileged reproduction over improvisation, no matter the shooting location.

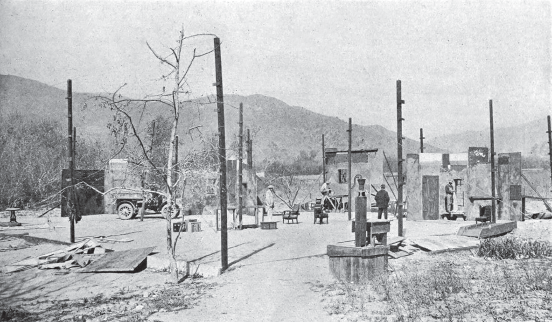

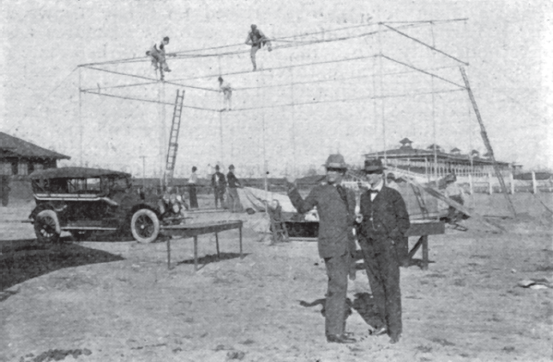

Even the era’s most transitory company, Kalem, which was known for operating without a studio, reproduced studio-like settings around the world. The company’s “Airdome studio”—more a standardized model for set construction than a studio proper—consisted of a series of vertical beams on which crew members could mount varying configurations of set pieces and sun screens to generate film sets.26 Designed with Kalem’s ambulatory film units in mind, the Airdome offered mobility, adaptability, and a way to make any location a studio set (fig 5.1). A photo in a July 1912 edition of Moving Picture World ’s “Studio Saunterings” series, for instance, claims to document the construction of an Airdome studio in Jerusalem.

Such efforts to make the studio transportable would reach their pinnacle in 1915 with director Romaine Fielding’s “Collapsible Studio” and an auxiliary mobile lighting system designed to bring studio-quality illumination to remote locations (fig. 5.2).27 Developed during Fielding’s employment with Lubin, the studio consisted of a numbered series of wrought iron pipes and joints, much like the nineteenth-century modular greenhouses developed by Crystal Palace designer Joseph Paxton. Ranging from twenty-six to thirty feet in height, the studio covered 1,200 square feet of working space, all covered in a double layer of canvas sections mounted on the iron skeleton to make the studio waterproof. When packed up, it would fit in a 60-foot baggage car for transport to a new site where a trained crew of ten could reportedly rebuild it in six hours. The mobile lighting unit, also developed by Lubin, was transported by a Mitchell automobile and designed, as Motography put it, “for field work where it is impracticable to run wires for miles in order to get night photography.”28

To be sure, even with these elaborate efforts to maintain studio norms outside studio walls, shooting conventions did change as migrating filmmakers encountered new kinds of landscapes. Film technologies and studio techniques were by no means immutable. In their early struggle to find a suitable form for western scenes, D. W. Griffith and Billy Bitzer, for instance, initially responded to unfamiliar western settings by relying on techniques used for eastern shooting and in the studio. As Simmon describes, they used “iris lens effects to limit the surrounding white space” of barren landscapes or simply steered away from the most distinctive of western terrain, instead seeking “woodsy landscapes that could be molded to eastern framing.”29 But they also combined these approaches with new methods, including higher camera angles that brought more of the ground into the frame (to reduce the emptiness of the sky), long shots from high vantage points (again to emphasize varied terrains over open skies), and the use of rock outcroppings and posed figures to anchor otherwise empty settings.30 In short, Griffith and Bitzer had to adapt studio techniques to unfamiliar, non-studio spaces. Put another way, just as much as filmmakers sought to capitalize on the West’s uniqueness and authenticity, they also worked to overcome or tame new landscapes using both familiar studio techniques and new adaptations of them.

On a more practical level, filming the natural landscape could never be divorced entirely from studio practice. For traveling filmmakers, the studio remained essential for processing and printing film as well as for filming the interior scenes with which they assembled narratives. For filmmakers who went west or south, the initial seasonal travel schedule meant studio scenes simply had to wait for the return home. But in the east, filmmakers developed a rhythm of moving between interior and exterior shoots. Nearby towns such as Coytesville and Shadybranch, New Jersey, became common destinations for location filming commutes from Manhattan. Before Griffith began leading Biograph filmmaking trips to California, for example, the company regularly alternated between its Fourteenth Street studio and location shoots in nearby Fort Lee, New Jersey.31

Soon, however, even these short trips seemed superfluous. Instead, filmmakers simply moved closer to their favored shooting locations by taking advantage of cheaper land to establish studios in New Jersey. Fort Lee, in particular, made a desirable alternative for New York City filmmakers in search of natural settings and/or shelter from the Motion Picture Patents Company. In 1910, the Champion film company became the first to establish permanent facilities in Fort Lee when its owner, Mark M. Dintenfass, moved there to escape the MPPC.32 Dintenfass’s initial studio, which Moving Picture World described as “unattractive” but “effective,” housed the usual necessities that filmmakers setting up shop away from their studio homes demanded. It included prop, set design, and storage rooms, developing and printing facilities, and a machine repair shop.33 In 1911, emboldened by the company’s early success, Dintenfass added a glass-and-iron extension.

Over the next three years, the town that one writer had called an “indefinite place” became a small studio center.34 New glass studios, notably including the Willat Film Company’s large vaulted studios, which would later be home to the Triangle Film Corporation and William Fox’s East Coast productions, made it clear that the industry was there to stay. Fort Lee also emerged as an outpost for a growing contingent of French film companies seeking to avoid import taxes by producing films in America.35 Eclair arrived first, building a glass studio there in 1911, and Alice Guy brought her Solax company to its own glass studio the following year. In 1914, Eclair’s president, Charles Jourjon, started a second company in Fort Lee, the Peerless Feature Producing Company, and built another large glass studio for it.36

As the construction of such studios suggests, even as filmmakers made compelling vistas the basis for film aesthetics and emerging genres outside the studio, they continued to fall back on staged productions. Interior scenes and environmental control remained desirable, whether in the rural East, Florida, Texas, or under Southern California’s (usually) sunny skies. The quest for light, authenticity, and nature never entirely detached filmmakers from studio techniques; rather, the further incorporation of technologically reproduced natural scenes into longer narrative films contributed to cinema’s increasingly holistic production of artificial film worlds.

The seasonal exit from urban studios thus ultimately found filmmakers in new studios, especially as it became clear that southern and western locations would be more than winter destinations. For their new infrastructure, companies like those based in Fort Lee imported studio designs from New York and Chicago. In Southern California, in particular, this return to the studio achieved a scale that would make Los Angeles the preeminent filmmaking capital of America.

REMAKING THE STUDIO IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA

In 1911 the Nestor Company opened its western studio at the corner of Sunset Boulevard and Vine Street. As the first in Hollywood proper, Nestor’s studio represents the spatial and symbolic origins of the industry that would come to define and dominate the medium’s modern narrative form under the name of the “studio system.” Taken as an architectural space, however, it was far from modern. In fact, the studio bore closer resemblance to the first exterior production stages from cinema’s first half decade than to the large Gaumont, Pathé, and Vitagraph studio factories discussed in the previous two chapters.

Indeed, studios in Southern California did not progress steadily toward the buildings that defined modern Hollywood. Rather, due to a number of factors—including the ephemeral nature of early filmmaking in the West, filmmakers’ initial focus on location shooting, and the generally good weather conditions that made exterior stages more viable than back East—the studio would go through an uneven process of development, reinvention, and adaptation before arriving at its more “modern” form in the second half of the 1910s. This process helped shape the future of filmmaking (and Hollywood) by making a blend of interior and exterior filmmaking spaces and shooting practices common at studio complexes, where filmmakers split time between open-air stages, glass house studios, and backlot sets.

Los Angeles’s first production spaces were emblematic of the return to studio origins witnessed across Southern California. As in so many places before it, studio production in the city began, quite literally, on a back lot.37 Located behind a downtown laundry, it was rented in 1909 by Selig director Francis Boggs and would be Selig’s Los Angeles home for a brief spring season in which Boggs oversaw the productions of The Heart of a Race Tout and In the Power of the Sultan, the first staged fictional films made entirely in California. In addition to this backlot space, Boggs also set up an open-air rooftop stage next door, where he directed a one-reel version of Carmen.38 As spring arrived, however, the company abandoned each of these stages and traveled north to film westerns on location while its business manager scouted sites for more permanent studio facilities.39

When they returned in August, the Selig troupe moved a few miles north of downtown to Edendale (today located between Echo Park and Silverlake). There, Selig had acquired a small lot of less than an acre containing a house that Boggs used for offices and dressing rooms. Alongside it, he laid a 16 × 20 foot cement pad to serve as a stage.40 Much as filmmakers had done in the mid-1890s, Boggs and his crew built painted backdrops on the ground and filmed scenes on this open-air set.

Selig’s open-air productions remained the norm during the first years of Los Angeles–area filmmaking. Even as companies moved away from the seasonal model that made ephemeral stages a sensible option, they did not immediately seek to establish glass-enclosed studios equipped with electrical lighting like those in their eastern headquarters. Favorable weather conditions and filmmakers’ initial focus on location shooting meant that producers did not need to devote substantial resources to what might ultimately prove to be only a passing trend.

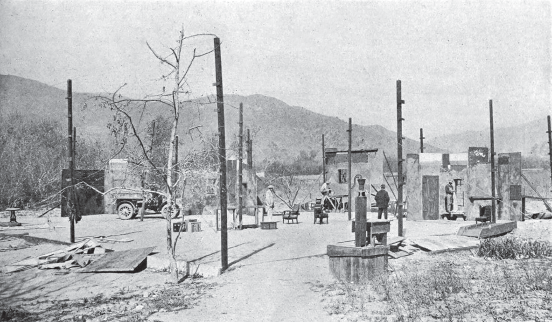

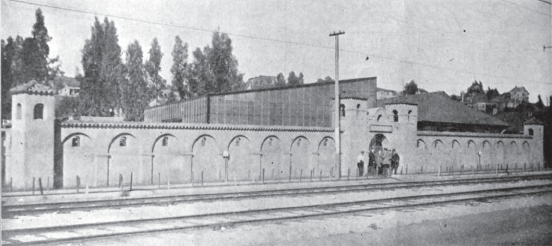

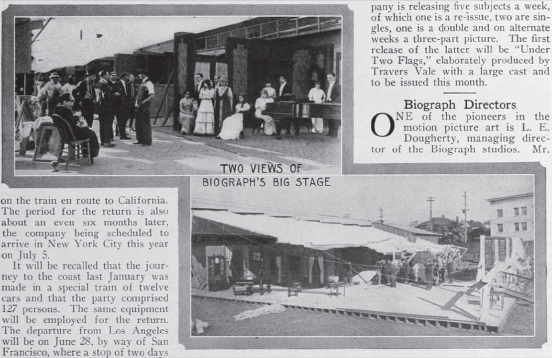

Instead, studio spaces and systems of environmental control more akin to cinema’s first decade reappeared in Southern California. Following Selig’s lead, in late 1909 the Bison company set up shop only a few blocks away in Edendale. There, Adam Kessel and Fred Balshofer oversaw the transformation of the lot’s unused wheat storehouse, barn, and several small shacks into a laboratory, offices, dressing rooms, and an open-air stage. The latter included a system of muslin cloth shades for regulating the sun that echoed those used by Méliès in his first glass studio.41 Similar versions of Bison’s light-regulating system became the norm at competing studios. D. W. Griffith’s Biograph troupe, for instance, used just such a shading system at its first facilities in downtown Los Angeles (fig. 5.3). Built at Washington Boulevard and Grand Avenue in 1910, the studio included an approximately 2,000-square-foot exterior stage equipped with a system of vellum cloths on wires.42 In Hollywood, Nestor’s studio included a 40-square-foot raised wooden platform with a comparable configuration of muslin cloths controlled by a network of wires.43 And in nearby Glendale, the Kalem company established a version of its Airdome studio in 1911.

As these light-regulating techniques suggest, filmmakers still demanded control over the filming environment, even in the most favorable weather conditions. Indeed, no climate was beyond reproach. Filmmakers soon discovered that even Edendale was not always the filmmaking “Eden” that many had come to expect. Weather statistics cited in the film trade press advertised “320 days for good photography” each year, but even among those days, more than half included some clouds, often including morning fog.44 To be sure, these conditions trumped those found back East, but filmmakers hoping for a favorable climate year-round were in for an unpleasant surprise.

Reports from Moving Picture World’s western correspondent attest to the delays that plagued film companies, often for days and even weeks at a time. In February and March 1911, for instance, nearly a month of rainy weather halted film production. While Selig and Bison were able to rely on their reserves of finished films, other companies, including Biograph and Pathé, could not meet the usual release dates.45 In June 1913, more than a week of clouds—what today’s Angelenos refer to as “June gloom”—“[cut] down the light to such an extent that most of the companies feared to risk photographing lest they get flat and undertimed pictures.”46

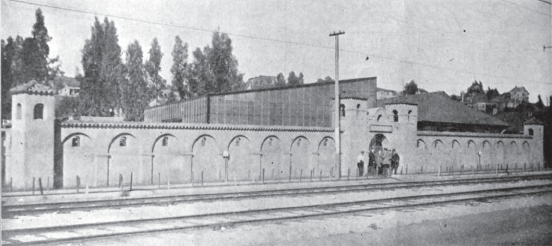

Such bouts of bad weather must have convinced the owners of the region’s larger producers to devote greater resources to studio infrastructure, a process already under way. Given the large demand for films in the nation’s expanding theater chains and the success of films produced in California in its first years, companies could justify expanding their land holdings and improving their facilities. Among their first concerns, producers sought to protect studio resources and their players from the weather and curious passers-by. Selig, for instance, wasted no time surrounding its Edendale studio with an ornamental wall that provided privacy, protection, and prestige (fig. 5.4).47 Designed in the Mission Revival style, Selig’s wall would become a model for companies in the region seeking to boost their corporate image and appease local residents’ concerns about the new industry by projecting prestige and matching local aesthetics through ornamental architecture.48

Inside the walls, more banal structures provided the functionality that made studios run smoothly. The earliest studio building permit applications filed during this period call for an endless array of “sheds” designed to house props, painted backdrops, tools, and automobiles. At Selig, for instance, construction plans approved during 1910 included a 3,300-square-foot shed at a cost of $800, alterations to a 1,100-square-foot building with dressing rooms, an office, a darkroom, and a cellar ($500), 500 square feet of additional dressing rooms ($150), and a 250-square-foot auto shed ($50).49 While Selig was the earliest company to devote such resources to its western infrastructure, similar patterns would be found at nearby studios over the next two years.

Early studio development was also not limited to companies with film units working in the region year round. Even Biograph, which remained only a seasonal presence, quickly established its own facilities. After their first season at the Washington and Grand studio in 1910, Griffith arranged for a more permanent site nearby at Girard and Georgia Streets (see fig. 5.3). The new studio, which Griffith opened in early 1911, again featured an open-air stage, now surrounded by offices, storerooms, and a developing plant.50 The studio sat unused during the first few summers, but each fall a studio employee would reopen it in preparation for Griffith’s seasonal arrival.

These early developments were only the prelude to the massive expansion of studio infrastructure that began in 1911. As more companies arrived and existing ones stayed beyond the winter season, permanent studios sprang up across the region. Alongside their open-air stages, companies began to add glass studios, some equipped with electrical lighting. Selig reportedly invested $75,000 in its glass studio in 1911, a plan mimicked at neighboring Pathé.51 At the nearby Bison compound, New York Motion Picture Company owner Frank Kessel put $30,000 into a glass studio equipped with Cooper Hewitt lamps.52 In April of that year, Moving Picture World ’s western correspondent Richard Spencer, citing eight companies with regional studios, first anointed Los Angeles “a producing center.”53

The expansion had only just begun. During 1912, the number of producers rose to at least thirty-five, and studio infrastructure blossomed thanks to what one report described as “a wave of prosperity” among local motion picture manufacturers.54 Vitagraph opened a western branch in Santa Monica, where it produced films on a “canvas covered studio.”55 Kinemacolor revamped the former Revier laboratories and added six new buildings at 4500 Sunset Blvd.56 Keystone took over and renovated the Bison studio in Edendale.57 Kalem added an additional studio in Santa Monica, where it refurbished a former Pacific Electric Company rail terminal.58 Gaston Méliès briefly made a studio in Santa Paula his company’s headquarters.59 And finally, IMP, Rex, Powers, and Bison, all operating under the Universal banner, began producing films at studios in Hollywood, Brooklyn Heights, and at the Oak Crest ranch, future home of Universal City.60

By the year’s end, one estimate put the film industry’s investment in the region at more than $1,500,000.61 That estimate deserves some skepticism given the industry’s and local boosters’ stake in crowning Los Angeles the center of American cinema. But there can be little doubt that studio infrastructure expanded dramatically and played a critical role, not only in booster rhetoric but also in the industry’s development.

The seemingly incessant arrival of new film companies and large-scale expansion by existing ones came with growing pains. By 1914 no fewer than fifty companies had built studios, with plans for new buildings or studio improvements reported almost weekly. Moving Picture World ’s correspondent Clark Irvine marveled in one 1914 report, “And they still come!”62 The increasingly saturated market pushed some new companies out of business.63 Others faced heretofore unseen problems, including a lack of extras in early 1913 that some attributed to the number of companies now offering regular work.64 Most significantly, the industry’s physical expansion and the number of companies vying for and exploiting local settings created tensions around access to and treatment of filming locations. Those tensions and the further expansion of studio infrastructure by the largest companies would help define the emerging idea of “location” and eventually make the studio backlot a critical new feature of California film production.

“PROSPECTING FOR LOCATIONS”

So pervasive was the studio ideal in the early 1910s that even those calling for more non-studio production could do little to avoid its rhetorical pull. A telling case appears in Moving Picutre World ’s 1911 series “Letters of an Old Exhibitor to a New Film Maker.” In the third installment, the wizened industry veteran warns young filmmakers not to “stick too close to your indoor studio or outdoor annex studio.” Proclaiming that “we exhibitors . . . become as familiar with film makers’ studios as with our own backyards,” he cautions that audiences, too, “feel the repetition” of studio settings, and even outdoor annexes “of generous size” will do little to cure the monotony. The solution, he counsels, is to “Go out into Nature just as often as you can.” But his reasoning for this shift makes clear that to do so was not so much to sever ties with the studio as to reproduce its logic in a better place. Indeed, “the best of all studios,” he declares, “is Nature.”65 This tendency to evaluate nature according to studio ideals—and not, importantly, the other way around—would soon shape the development of location shooting and the studio backlot.66

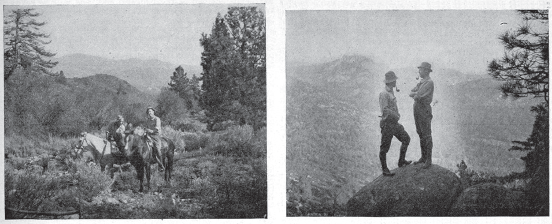

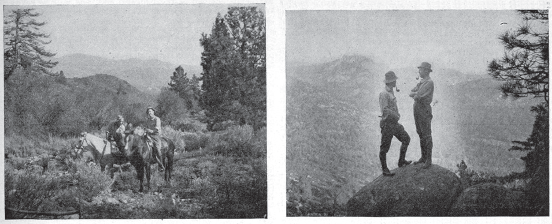

Studio designers had been perfecting “Nature” for almost two decades, and as filmmakers returned to the great outdoors, they brought those studio principles to their search for natural settings. A 1914 photograph of Jesse Lasky and Cecil B. DeMille at the newly acquired Lasky ranch in the San Fernando Valley suggests the logic they used to do so. Out on horseback, Lasky and DeMille are, as the caption describes, “prospecting for locations” (fig. 5.5).67 And prospects must have seemed good. The photograph neatly encapsulates the rhetoric that dominated popular discourse about California locations in the early 1910s. Framed perfectly in the midst of verdant undergrowth, plentiful evergreens, rolling hills, and distant peaks, all bathed in plentiful sunlight, these film “prospectors” have already struck gold. An accompanying photograph makes the argument complete—Lasky and DeMille, on location, on top of the world, at the top of the motion picture industry. But, what, we might ask, were they looking for at 5,000 feet? What was a “location” for a filmmaker in 1914? What did it mean to “prospect” for one? And how would they even know when they found one that was suitable? The idea of Lasky and DeMille “prospecting” for locations points to a set of answers that lies in the importance of the studio.

The term “prospect” neatly encapsulates both the emerging idea of “location”—as a resource that needed to be secured, controlled, and efficiently accessed—and the means by which California filmmakers did so. As it appeared in the caption accompanying Lasky and DeMille’s photo, prospecting points to the similarity between prospectors’ pursuit of mineral deposits—especially with reference to the California gold rush and Los Angeles’s growing oil industry—and filmmakers’ search for suitable backdrops. Indeed, the idea that a location, like a limited resource, might be depleted or overused appears repeatedly in this period, as in a 1913 account of a production company organized to tour the globe, “stay[ing] in each location until it is pumped dry of interesting pictorial matter.”68 As a metaphor for how enterprising film companies might strike it rich by “mining” the California landscape for suitable backgrounds, prospecting points to the real value that locations would have as resources for companies in need of raw materials for filming.

The term also suggests the ways that filmmakers approached locations with established ideas about what a suitable filming site might look like. In its early use, “prospect”—from the Latin prōspicere, “to look forward”—could refer both to a view of landscape and the formation of “mental pictures” and “anticipated events.”69 This idea of forming a mental picture and anticipating views well describes what Lasky, DeMille, and filmmakers like them were doing. Prospecting for locations began from an existing idea of what a location would look like. And that idea was in no small part related to how locations were anticipated in film studios. There, location meant painted backdrops—including western landscapes—stored in scenery rooms and called upon when a film idea anticipated a particular setting.

In many filmmakers’ minds, location must have become much the same as studio scenery—a resource that could be prepared, stored up, and saved for future use. By the 1920s, maps of studio backlots prepared by professional studio prospectors (aka “location men”) packaged this system in easy-to-read formats.70 But already in the early 1910s, such ideas were a common feature of discourse about California in the popular and trade press and in studio publicity. In his 1911 report about the rise of Los Angeles as a producing center, Richard Spencer noted that, in addition to finding “exteriors from a tropic to a frigid background, and from desert to jungle,” one could just as well film scenes requiring an “Atlantic City or Coney Island Background” in California rather than New York.71 A 1916 Los Angeles Times article would similarly note that the California-based director could easily drive from Malibu “to the (apparent) Sahara of Africa, the desperate desolation of Central Asia or the storied wilderness of our own pioneer West.”72 Put another way, California was like a well-stocked scenery supply closet; one need only call up the right background and start filming.73

Such ideas were commonplace in film studios back East, where the ability to fake a location was a point of pride. In 1911, for instance, a Moving Picture World reviewer created an ideal publicity item for the Selig Polyscope Company when he mistook a film made on location in Japan for a studio set.74 Selig took this mistake as an unwitting complement about the quality of its studio fakery and responded by proudly proclaiming,

when such authorities cannot distinguish between actual scenes from life . . . and scenes built and photographed in the Selig studios—when they believe that these actual ‘scenics’ are only Selig studio productions, and on the other hand mistake Selig studio productions for actual taken-from-life ‘scenics’—then it is an assured and conceded fact that Selig nature reproductions have reached the height of perfection.75

It should come as no surprise, then, that many filmmakers in Southern California believed they could make local settings stand in for any place in the world. They had, after all, already made a business and an art out of imagining that the interiors of empty buildings could be made to do the same.76

Thus, even if the first filmmakers in Southern California were enticed by variety, diversity, and all that was new about western landscapes, for many film companies locations quickly became new places in which to extend the old, reliable working practices of studio filmmaking. Put another way, they became “studios beyond the studio.” This extension of the studio to locations far and wide would come full circle not only on Hollywood studio location maps in the 1920s, but especially on the studio backlots where this way of thinking about location as a resource would be systematized. Ultimately, “prospecting for locations” meant finding filming sites defined by three prosaic qualities: accessibility, control, and efficiency.

DEFINING LOCATION

In August 1913, Moving Picture World ’s western correspondent P. M. Powell reported that two problems threatened the film industry’s future in Southern California. One was price gouging by local merchants seeking to profit on filmmakers’ apparent willingness to pay anything to get props and supplies.77 The second problem—again involving locals’ efforts to profit from the growing industry—centered on filmmakers’ ability to shoot on non-studio property. As Powell described, “directors find it harder and harder to obtain backgrounds or ‘locations’ without submitting to a ‘holdup.’ ” This “holdup,” he specified, involved a cash payment—“$5 or $10, or even $25”—demanded by property owners who had come to learn that directors who had “decided on a certain background for a scene” were willing to pay to secure it.78 This practice and the more general recognition among film companies that quality shooting space was a limited, valuable, and increasingly contested resource would help shape the emerging definition of location.

As Powell’s use of scare quotes suggests, “location”—as something to be distinguished from backgrounds or sets—had only begun to enter the industry’s vocabulary in 1913. Although the term was common in the industry in its general sense as a particular place (e.g., to build a theater or studio, to position a projector, etc.), it did not begin to acquire its industry-specific connotation until 1913.79 Even then, location was only one of the terms with which writers tenuously signified the specificity of film spaces. In his July 1913 guide to “Motion Picture Making and Exhibition,” for instance, John B. Rathbun instructs scenario writers to “remember that every time that the surroundings or ‘locales’ are changed you must have a new scene and a new subtitle.”80

More significantly, as examples such as Rathbun’s instruction indicate, “locales” or “locations” did not initially signify non-studio spaces. Rather, “location” also became a common way of describing the shooting sites on film company properties that blurred the line between studio and non-studio filming. A 1913 article about the “Lubinville” studio outside Philadelphia, for instance, notes that its 500-acre Betzwood estate included “almost any location needed in the taking of pictures.”81 Similarly, in his 1914 account of the motion picture industry, Robert Grau emphasizes the filming spaces at Selig’s new Los Angeles zoo: “here will be found sets and locations for all classes of plays, from the primeval to the last word in modern presentations. Jungles, morasses, forest effects, battle fields—all will be at hand for the busy producers.”82

In contrast, by the 1920s studio and location had acquired their commonly understood distinction. David Boughey’s 1921 study of the film industry, for instance, makes clear that a “location” designates a non-studio site found by “the poor location man,” who “must find some spot, not too far removed from the studio, or at least from civilization, which, with artificial aid, will resemble as near as may be the glowing description of an earthly paradise.”83 Austin Lescarboura similarly differentiates between studio “interiors” and shooting “on location” and notes that “the advent of new efficiency methods” have made finding locations the domain of studio specialists.84

Before Hollywood systematized it, however, “prospecting for locations” remained the domain of producers and directors like Lasky and DeMille. As more and more filmmakers went out in search of suitable settings—often looking ahead to the same studio-inflected ideals—producers (and property owners) recognized that locations were neither endless nor equal. In this context, the idea of “location” emerged as an issue of access. A location was something to be obtained and controlled, and it also became a commodity to be traded.

Indeed, while we might doubt that film companies really contemplated leaving the region over the local “holdup game,” we can be sure that they were taking steps to ensure access to locations. Selig, for example, treated at least one kind of location—the Spanish mission—as a prized commodity. In 1912, recognizing, one might surmise, their iconic value for evoking western and historical settings, Selig secured exclusive filming rights with all of the local missions. As a result, when Pathé producer James Young Deer wanted to make a film about the early days of Los Angeles, he paid the company’s scenery artist to use photographs of a local mission to reproduce a faithful replica of it on a “big open space” (not yet referred to as a backlot) behind the company’s studio in Edendale.85

This problem of accessibility was not limited to specific places or building types, but also extended to the region’s supposedly limitless natural settings. Griffith Park, in particular, became a highly contested site that again brought film companies into conflict with the local community and threatened to limit the industry’s access to local scenes. Later immortalized in the telling, if apocryphal quote “a tree’s a tree, a rock’s a rock, film it in Griffith Park,” it was already described during this period as one of the most photographed places in the world.86 But the park had also been a source of conflict between local residents, park officials, and film companies from the earliest days of filming in Los Angeles. As Eileen Bowser notes, Angelenos often reported stumbling upon deserted temporary sets.87And by 1911, their complaints about filmmakers’ uses of the park included the charge that crews tried to control access by harassing motorists and pedestrians who interrupted scenes; that they scared animals by firing blank cartridges; that they left litter and damaged trees and shrubs; and even that one company had intentionally set fire to a ranger’s cabin in order to get a realistic scene.88

These charges led to calls for a ban on filming in the park, and an ensuing hearing in January 1911 resulted in stricter regulations governing its use. In addition to the blanket provision that a company’s filming permit could be revoked at any time, the new rules included two notable requirements. First, that “the scene to be used must be subject to the approval of the park foreman and superintendent.” And second, that film companies “must permit no waste, must not cut, mutilate, damage, or destroy any flowers, trees, plants, or other growing things in the park.”89 The requirement for scene-by-scene approval and the potential to have one’s permit revoked at a moment’s notice threatened access to one of the most sought-after locations in the region. What’s more, the edict against transforming the park in any way meant that filmmakers no longer had the kind of control over locations that previously allowed them to manipulate settings to match anticipated ideals.

At least some filmmakers may have responded by cleaning up their act. The following month, Richard Spencer reported that one Griffith Park ranger had praised Fred Balshofer for the Bison Company’s “orderliness and cleanliness . . . in leaving the scenes in as good condition as they found them before taking pictures.”90 Even accepting the verity of such reports, which may have been little more than public relations ploys facilitated by the trade press, the park continued to be a contested filming location where filmmakers were subject to further rules and regulations.91 Not surprisingly, companies thus also sought new places to make films, including nearby locations such as the mountains near Malibu and further afield in areas like Bear Valley, which became a favorite filming location for Bison and Selig in 1912 and later for Vitagraph and Lasky.92

More significantly, they also took steps to secure access to desirable locations by buying up tracts of land, in some cases by the hundreds and thousands of acres. In this period of rapid and massive studio expansion, new studio buildings went up constantly, and company land holdings exploded from small lots to ranches covering 20,000 acres. On the small end of the scale, Pathé acquired thirty-five acres above Edendale in 1912, and the same year the Brand Motion Picture Company established its studio on forty acres near Burbank.93 Such figures were soon dwarfed by the acquisitions undertaken by Universal, Ince, and Lasky. In 1912, Universal reportedly purchased 20,000 acres at the Oak Crest ranch in the San Fernando Valley and added another 230 acres two years later.94 By 1914, the New York Motion Picture Company had leased 18,000 acres for “Inceville” in the Santa Monica Canyon, while Lasky and DeMille were out prospecting on 20,000 leased acres of their own.95

These corporate land grabs further reduced the distinctions between location and studio filming. Privatization meant that filmmakers no longer needed to fear losing their favorite filming sites or having to obtain permission before executing a scene. By assuring exclusive access for their own filmmakers, the largest companies also limited their competitors’ prospects—underscoring location’s status and value as a key filmmaking resource. Studio buildings could now be physically closer to shooting locations, a proximity that contributed to even greater continuity between the practices undertaken on each. This combination of the new legal boundaries that governed exterior shooting sites and those spaces’ physical convergence with studio buildings and the filming practices used in them would define the Hollywood backlot—a hybrid space, both studio and location; neither studio nor location.

THE STUDIO BEYOND THE STUDIO

The backlot would represent the culmination of filmmakers’ competing desires for authenticity and reproducibility; spatial freedom and predictability; and the natural environment and its controllable facsimile. These studio-like exteriors—outside spaces where filmmakers could either build sets like those in the studio or return, again and again, to landscapes that became set-like in their consistency—typify the ways that cinema enframed the natural environment, transforming nature into a standing reserve for technological reproduction. Responding to the same kind of impulse that saw filmmakers flock to the artificial environments of international expositions, backlot filmmaking made natural environments cinematic showcases. Put another way, they systematized the emergent idea that nature was a studio.

In a sense, filming on studio ranches merely brought the practices being utilized away from studios back into their legal domains, where location would come to be structured, industrialized, and named. The backlot’s physical extension of corporate control reduced the already small practical difference between the studio and non-studio techniques being used. On their own ranches, where they could build sets and modify landscapes at their leisure, companies wouldn’t need elaborate mobile studio systems such as Kalem’s Airdome and Fielding’s collapsible studio.96

Control of the filmmaking space—which could no longer be assured on public land like Griffith Park or on non-studio private lots where owners might demand a shooting fee—allowed for more systematic and efficient methods of cultivating the landscape according to filmmakers’ needs. As Lasky put it, the studio ranch offered the great advantage “of making use at some subsequent time of properties . . . which we have [already] gone to great expense [to build].”97 Thus, whereas Bison was forced to prepare, in Richard Spencer’s words, “crate after crate of scenery and ‘props’ ” when it went to Bear Valley in July 1911, now they could rely upon preexisting sets and supplies stored nearby.98 And they could shape and manipulate the land as much as they liked without the need to repair it or repeat the process when a future shoot called for the same setting. In short, they could manufacture locations.

At the Bison 101 ranch in Santa Ynez Canyon, for instance, filmmakers complained that during the summer the land often failed to deliver the views that they had anticipated. In response, the New York Motion Picture Company built a waterworks to refresh lake and river beds that needed to be “brought to life again.”99 At Inceville, infrastructural upgrades—including an aqueduct, electrical plant, and the construction and maintenance of roads—facilitated efficient access to a diverse repertoire of locations and semipermanent set pieces. As one reporter described, “[Ince’s] shops construct everything from uniforms and furniture to houses. . . . His range of locations travels in leaps and bounds from . . . the broad Pacific to the wild West, mountain life, Ireland and the Orient and in fact to every country save the extremely tropic.”100

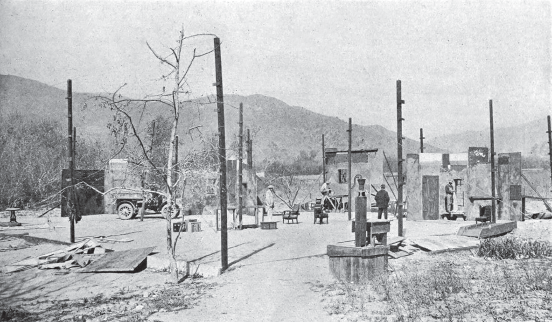

On the other hand, greater control often meant more waste, as when companies chose to destroy those sets and scenes without fear of reprisal. Indeed, by providing space for the massive sets that would define Hollywood’s earliest versions of the silent epic, the development of the backlot not only shaped film content and form in the mid-1910s; it also encouraged that spectacular genre’s attendant material excess. This tendency would seem to confirm the fears of those invested in saving Griffith Park from film companies bent on destroying it. As Lasky described in 1914, “when the property is ours we can do as much damage as the interests of the picture may require.”101 At Inceville, Thomas Ince reportedly instituted the practice of burning at least one building each month, both as a tool for visual spectacle and as a way of training the studio’s fire department.102 And at Universal’s grand opening in 1915, featured events included the destruction of an entire frontier village set by an artificial flood.103

This cycle of construction and destruction defined huge backlot cities such as Ince’s Irish Village and Dutch city or Universal’s version of Cairo, which was destroyed in a 1915 rainstorm along with neighboring versions of New York City and “little Bombay.”104 Contemporary observers marveled at the unlikely juxtapositions that, although nothing new to studio practice, became newly visible on large exterior sets. On these “great ranches,” as a 1915 Los Angeles Times article described them:

you are likely to chance upon big armies of cowboys riding madly to the exigencies of a frontier tale . . . or glimpse a crowd of actors in quaint costume and make-up for a tale of bygone Spanish days . . . [or] you may happen upon an oriental village . . . or it may be ancient Greece . . . or you may find yourself on the battlefield of the Civil War.105

As another article describing Los Angles as a “Great Backdrop for the World” suggests, this celebration of the backlot’s malleability also included a temporal dimension. These landscapes offered a space “where may be enacted . . . almost any other land or time.”106 By extending the studio’s juxtaposition of real, unreal, and often-incompatible times and spaces, the backlot became both a new tool in and an outward manifestation of film’s role in the modernity-defining collapse of traditional notions of time and space.

Studio backlots provided filmmakers with the predictability needed for rapid productions that were possible with painted backdrops, all while also offering audiences seemingly authentic natural spaces. These studio-owned spaces became preserved forms of nature—ordered natural settings framed and stored for technological reproduction. Indeed, the backlot’s transformation of “authentic” landscapes into studio technologies exemplifies the ways that cinema contributed to nature’s changing status as something to be technologically reproduced or replaced by its artificial likeness. In their treatment as objects for reproduction, the backlot’s seemingly natural settings became technological spaces. Here, film companies could store and preserve various versions of nature with which to create artificial film worlds.

In their treatment as controllable facsimiles of natural landscapes, backlot locations represented a cinematic version of what Martin Heidegger describes as nature placed on reserve.107 Just as, in Heidegger’s theory of “modern technics,” technology transforms nature into a standing reserve for exploitation, so, on the studio backlot, nature became a reserve for cinematic representation. Rather than seek out natural scenes, filmmakers had only to return to preserved, predictable settings that functioned as studio set pieces. Here, they used the camera to retrieve nature, as if from storage, for the screen. Extracted from their surroundings, these slices of backlot reality served as ready signifiers, both for real locations—Greece, Spain, or an “oriental village”—and for the natural environment. Like film itself, the backlot acted as a medium for storing natural scenes—a kind of stock footage not unlike the hours upon hours of snow scene recordings that companies collected in the mountains around Los Angeles during the winter for use later in the year.108

This treatment of the natural environment as a resource to be stored for mechanical reproduction fulfilled the same ambitions inaugurated more than two decades earlier in the Black Maria. Dickson’s recognition of the technological utility of capturing the sun for producing moving images helped establish a relationship between cinema and nature that continued in studios throughout the early 1900s and to backlots in the 1910s. Cinema’s contribution to the human-built world’s artificial reproduction of nature operated precisely on this dynamic of capturing natural resources, processing them through film technologies, and reproducing them for welcoming audiences.

The backlot thus represented the logical extension of cinema’s transformation of nature into another efficient studio setting. The expansion of the studio out of doors pushed its productions to ever-larger scales and more robust (if still ephemeral) architectural forms that were celebrated in films with lifelike sets such as Griffith’s Intolerance (1916).109 Here, cinema reached the pinnacle of studio realism through the utmost artificiality—architectural façades without interiors. These building-less buildings represented the same effort to reproduce features of the natural environment seen in the first studios, adding only a new focus on representational realism. More importantly, they mark the clearest expression of studio cinema’s place in the production of the human-built world of industrial modernity. On the studio backlot, the artificial environments created in the first studios became seemingly inhabitable cities that, when processed from film to screen, bore virtually no distinguishing features from real built space.

These studio-built locations helped satisfy the need for consistency and efficiency that gave rise to massive exterior stages such as Universal’s row of sixteen sets, the epitome of the mass-produced studio efficiency inaugurated a decade earlier back East and in Europe. By 1915, these same needs for access, control, and efficiency had driven most companies in Southern California to build glass-enclosed studios, usually with electrical lighting, ensuring that location and studio filmmaking would remain closely tied in the early days of Hollywood.110

During this period of studio expansion, the idea of location that had been shaped by conceptions of space developed in earlier studios also circled back around to shape the new studios themselves. As larger companies such as Universal put more and more time and money into planning and designing their studios, they recognized that new studio buildings could satisfy their need for consistent, efficient access to a variety of locations, and they built those locations into studio architecture. When the American Film Manufacturing Company built its Santa Barbara studio in 1913, for instance, it designed the exterior in the popular Spanish mission style, but the interior was designed so that, as one article described, “every foot of building and grounds [will be] of a style that will lend themselves to the taking of moving pictures.” Its features included two “set” gardens (one for a “tropical scene”), an 18 × 36 foot reservoir with a “pond effect,” and a grape ramada, all designed as potential film sets. The interior buildings would be “as handsome as any Montecito estate,” and the exterior wall and smaller interior ones could be used to “add a rustic effect.”111 In its drive for filmmaking efficiency, American imagined that every space was potentially a studio set.

The best examples would be found at Universal’s aptly self-described “Chameleon City.”112 As one advertisement enthused, “Universal City is so cleverly constructed that at a moment’s notice its entire architecture can be changed from a replica of ancient Greece or Rome to a modern villa—from the laborer’s hovel to the King’s Palace.”113 Its bridges could be “altered from a Roman arch to an American trestle—from an English causeway to a Japanese pontoon,” and its artificial lake and “Universal River” could “float any craft from an Indian Canoe to a full-rigged ship.” It included a stadium designed “to stage every kind of play calling for out-of-door sports—from the county fair trotting meet to the Indian Durbar” and a tennis court available for filming and amusement. And it included “every sort of dwelling from the modest bungalow to the twenty-room mansion.”114 In short, the studio itself became a studio set.

In its combination of manufactured locations, reusable backlot cities, and studio buildings designed to mimic any imaginable setting, Universal City marked the height of the efficiency, accessibility, and control that came to define filmmakers’ approach to Southern California. Far from creating “Nothing Like It,” as one advertisement claimed, Universal City was the epitome of filmmakers’ search for spaces in which everything could be made alike.115 Few companies could afford to produce these conditions on so large a scale, but in the latter half of the 1910s, they would become the industry ideal that defined Hollywood production in the “studio system.” Here, filmmakers systematized a method for reproducing any imaginable world by mimicking and re-creating real spaces on screen using functional facsimiles built on studio stages or managed on backlot sets. To be sure, filmmakers still left their studios in search of “natural” locations, but many opted for the efficiency and environmental control offered inside the studio walls. For even if, as one 1912 article had described, it seemed “that Nature had planned this locality with foreknowledge of the advent of the motion picture industry,” places like Universal City betrayed the enduring belief that the industry and its studios could still do it better.116

CONCLUSION: STUDIO ARTIFICE, STUDIO SPECTACLE

The often overlooked but far from unlikely return to studio stages that characterized the film industry’s shift to Southern California in the 1910s underscores the important role in industry practice that studios had achieved during the previous two decades. Even though natural light remained the ideal for quality-conscious filmmakers, and even as natural settings increasingly appealed to film audiences, studio infrastructure offered the efficiency, economy, and control that filmmakers needed to meet the demands of the transitional era. Studios met those demands by achieving new degrees of artifice that made sunlight and natural settings useful but often either inessential or reproducible. Backlots offered accessible, groomed, and adaptable sites for “location” shooting. And new studios came equipped, as one 1916 Los Angeles Times article so fittingly put it, “with ‘artificial sun.’ ”117

In a sense, film production had come full circle—from the studio to the “studio beyond the studio” and back again. The common ideas that, on the one hand, studios could reproduce features of the natural environment—even the sun—and, on the other, that nature itself was just another studio, suggest just how highly filmmakers had come to think of their ability to produce artificial film environments by reproducing real ones. It should come as little surprise, then, that they so quickly imported architectural designs and studio technologies from back East to support their new filmmaking operations out West. No matter how good the light was and no matter how diverse the scenery, the studio remained at the heart of the industry to which it would soon give a name.

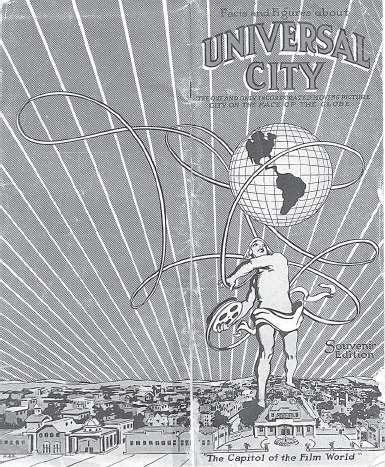

The departure from East Coast and Midwestern studios at the beginning of the transitional era would end with another somewhat ironic twist. The quest for natural light and “authentic” scenes that helped bring filmmakers to Los Angeles culminated in the behind-the-scenes tours that made the studio’s illusionary quality cause for celebration. In 1915, Universal City opened its doors to tourists and curious local residents who were beckoned into “the world’s only movie city.” At this “strangest place on earth,” as one poster described it, visitors were invited to experience the unique reality of studio production.

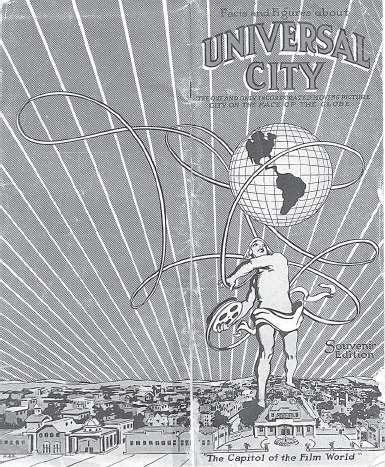

The cover of a 1915 souvenir tour guidebook neatly encapsulates the vision of filmmaking that had guided the industry’s development in California over the previous half decade (fig. 5.6). Towering over “The Capitol of the Film World,” Mercury or Hermes—gods of commerce and communication, travel, and movement between worlds—lassoes the globe with a filmstrip. What better metaphor for studio cinema’s power to transport viewers round and round a re-created world? The tour showed visitors how this re-creation worked by presenting a mélange of sensational and ordinary scenes—from cavalry teams, rough riding cowboys, and wild animal trainers to a U.S. Post Office, an ice plant, and a blacksmith shop. Through this combination of the spectacular and the banal, the tours revealed that Hollywood’s fantastic film spaces were built on the backbone of functional places.118

The Universal City tour’s blending of the spectacular and the banal reproduced the basic dynamic that studios and studio architecture had settled into by 1915. In their glass houses and on open-air stages and backlot sets, filmmakers strove for an operative balance between spectacle, illusion, and realism that they achieved by reproducing natural settings and realistic situations and creating real-enough imaginary worlds. Studio tours offered visitors a glimpse of the authenticity behind the illusion—the real techniques and even more banal day-to-day studio activities that structured their silver-screen fantasies. The studio tour worked through transparency—exposing the machinery behind the illusionary effects of cinema’s studio-produced artificiality. But rather than shattering the illusion, the tours promised to ensconce visitors even further in the spectacle of cinema’s built environments, physical and virtual alike. For even in unveiling the reality behind the dream, studio tours promised to enhance the spectacle by making the studio itself—cinema’s “dream factory”—just as worthy of celebration as the performances and performers hidden behind its walls.