CHAPTER ONE

BOURBON

POLITICS

When I interviewed Tom Bulleit in 2008, the Bulleit Bourbon founder told me something that forever changed the way I taste and write about bourbon. Bulleit sank into his Victorian chair and said, “Bourbon is a lot less about what’s inside the bottle and a lot more about what you tell people.” He called this the art of suggestion, pointing toward his ear, and continued by saying that marketing essentially commands the bourbon industry. Bulleit’s assessment was correct. The labels, stories, and even books about bourbon are greatly influenced by the publicists and marketers who represent the brands. They are the keepers of the history—and with so few of us trying to offer something other than these brand stories, the marketer’s narrative tends to own the marketplace of bourbon thought.

Bulleit’s art of suggestion, as he calls it, really begins as folklore in the 1700s. It grows to legendary status in the 1800s, becomes reported fact in the 1900s, and comes to irritate consumers in the 2000s.

The proof, age, and whiskey type are about the only things you can trust on an American whiskey label. Bourbon labels rival political ads for the most bullshit per square inch.

Michter’s is a historic brand with deep roots in bourbon legend. The original distillery owners claimed the site once served George Washington’s troops. The brand went bankrupt in the late 1980s; it’s now owned by Chatham Imports and is operating in Kentucky with the similar label.

Michter’s Distillery tells its consumers that George Washington once served its whiskey to his troops—an impossibility, as Michter’s didn’t exist in the late 1700s. But the original Michter’s Distillery was in Schaefferstown, Pennsylvania, owned by distiller John Shenk in 1753. The property boasted two of Lebanon County’s twenty stills and was just a farm distillery, like every other one in the area. General Washington was known to purchase whiskey from this area for his soldiers. In the 1970s, Michter’s owner Louis Forman exploited this faint connection, calling the newly named Michter’s “America’s Oldest Distillery” and craftily marketing it as George Washington’s beverage of choice for the health of his men—and by extension, the American nation. Fast-forward to the 1990s, after Forman’s company went out of business and Chatham Imports acquired Michter’s abandoned trademarks. Michter’s new website contained the same Washington story, only this time, the whiskey came from Kentucky instead of Pennsylvania. Michter’s became one of the many whiskey brands that purchased whiskey from other distilleries and bottled it themselves. However, some drinkers questioned the ethical practice of using the Washington story, since the whiskey was no longer coming from the same distillery. “The Washington story is a part of the brand’s history,” says Joe Magglioco, Michter’s president. And so, despite heavy criticism from a minority group of consumers (who frequently bombard Michter’s social media feeds with derogatory comments, calling Michter’s “scum” and “frauds”), the brand keeps its founding legend alive.

Another legendary marketing loophole lies with Elijah Craig, a brand named after a Baptist minister who was originally credited for inventing bourbon. The real-life minister is commonly referred to as the Father of Bourbon, but a 1970s whiskey scholar disputed this.1 We can all appreciate the fact that records proving Craig’s distilling capabilities might be lost—damn Google for not existing then!—but the legend actually revolves around his discovering the charred-barrel technique after a barn fire magically charred the insides of his barrels. Let’s think about this one for a second. How the hell is a fire burning the inside of a barrel but leaving the outside untouched? Perhaps Craig survived the only fire in history that selected what it burned. “Immaculate charception.”

Heaven Hill, the owners of Elijah Craig bourbons, admit they use this story tongue-in-cheek, and former Maker’s Mark CEO Bill Samuels told me that the industry needed to crown an “inventor” to help its marketing in the early days. Long before Heaven Hill established the Elijah Craig brand in 1986, the bourbon industry was carrying on the minister’s legend, likely to stick it to the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, which influenced Prohibition. You can’t help but chuckle about a Baptist preacher making bourbon, when several Protestant Christian denominations, including his own, frowned upon drinking.

Despite Heaven Hill removing the legend from its label, the Elijah Craig story still appears from time to time in legitimate magazines and newspapers. At the end of the day, it’s only whiskey, and the New York Times lifestyle editor isn’t hiring a freelance fact checker to verify bourbon’s origins.

Do people really care about legends influencing the historic truths?

Some do, and some don’t.

There’s a faction of whiskey drinkers known as whiskey geeks. These people belong to a few secret bourbon societies. (Yes, there are actual secret bourbon societies in the cyber webs of Facebook and the dusty basements of bars.) Bourbon is their love, their hobby and, for many, the reason why they wake up in the morning. They are lawyers, doctors, pilots, janitors, and people from many other walks of life. They take bourbon so seriously that they report distillers to the federal government for mislabeling products. These people heckle companies for any advertisement that misrepresents the whiskey truth, and they live to correct the Mr. Bourbon Know-Nothing who breathes fumes at you at the bar and tries to force his ignorance cloaked as knowledge on the public. I am a whiskey geek, and we are a passionate people who’ve become the de facto Whiskey Police, keeping brands in check in social media. We have become so powerful that some American whiskey brands pursue the geeks’ opinions in public forums. But we still represent a minority of the whiskey consumer base, and some brands just don’t care what we think.

MGP Ingredients is a conglomerate food and agricultural company that owns and operates a former Seagram’s distillery in Lawrenceburg, Indiana. It contract distills or provides sourced whiskey to many distilleries and bottlers. Many of its clients have failed to disclose their whiskey source and endured public scrutiny or lawsuits.

Members of the larger audience walk into a liquor store, pick up a bottle, and are intrigued with the label. They buy the product, drink it, and either like the whiskey or don’t. This audience is becoming affluent with its bourbon knowledge and is eager to learn more, but they do not immediately accept the aforementioned whiskey geeks’ policy of truth in labeling. In the beginning, these new consumers just want good whiskey. Then, they really start falling in love with particular brands and their backstories, and when they sometimes learn that a backstory is hyperbole, they either accept the half truths or blanket lies or they feel outright deceived.

Whiskey geeks frequently target Michter’s for their belief that the Pennsylvania legacy is a misrepresentation of the whiskey inside the bottle. But the parent company of Michter’s purchased the brand’s namesake when nobody else wanted it. That means they own the rights to the Michter’s name; should they not be allowed to market the original brand’s legacy? Another example is Templeton Rye Whiskey. Templeton, Iowa, is a small town that made a ton of illicit whiskey during Prohibition, even supplying Al Capone for his bootlegging operation. In the mid-2000s, a tan tin-sided building appeared on the main drag of Templeton with a few barrels out front and a tiny still inside. Shortly after this building was erected, Templeton aged rye whiskey started appearing on the store shelf. How was this possible? They’d just opened their doors and already had a well-aged whiskey? Was it magic? Nope. They purchased bulk whiskey from a former Seagram’s distillery in Lawrenceburg, Indiana, that was selling all of its whiskey to anybody and everybody just to keep the lights on. The Indiana distillery changed owners a few times, and the plant was nearly shut down, until its former parent company, CL Financial, developed the business model of selling aged whiskey to start-up companies like Templeton.

Templeton slapped the town’s true Prohibition story on its back label, and people fell in love with the whiskey. But when the truth was revealed—that the whiskey hadn’t really been made in Iowa—people were pissed off, and Templeton faced three class-action lawsuits under consumer protection laws.

This sort of thing is hardly new. Since whiskey companies have been in business, distillers have worked with other distillers or independent bottlers to provide whiskey for another company’s product. Today, these independent bottlers are called non-distiller producers (NDPs), a term coined by Bourbon Hall of Famer and whiskey writer Chuck Cowdery. NDPs are companies that do not own their own distilleries and instead purchase whiskey from somebody else. The whiskey geeks don’t mind the so-called NDPs; they just seem to get irritated with the backstories. Back in the 1940s and 1960s, the Stitzel-Weller Distillery was providing whiskey to the Old Medley Distillery and contract distilling for Austin, Nichols, and Company, while Glenmore Distillery sold hundreds of barrels to bottlers needing supply. The bottlers slapped their pretty labels on somebody else’s whiskey, they sold it to consumers who were happy to drink it, and nobody felt deceived. That was the business.

Back then, however, the Internet didn’t exist. Special bourbon forums, such as StraightBourbon.com, and other social media sites have given enthusiasts platforms to share information about recipes, water, distillation techniques, and history. Back in the old days, consumers didn’t have access to much of this information, and distillers could get away with changing a recipe. It’s more difficult for bourbon makers to get away with stretching the truth today.

When Maker’s Mark watered down its bourbon whiskey to “meet demand” in February 2013, for example, the general American public called the iconic whiskey brand greedy, and international social media blew up with pure rage. Core fans reminded Maker’s Mark that they once promised that they would never change their product. But they did change it, lowering the alcohol proof from 90 to 84, and fans spoke. “You BASTARDS!!!! I love Maker’s! But I’m going to switch! Hope you’re happy!! Because I’m pissed,” wrote fan Tony Aguilar on the Facebook announcement.

The online outrage pushed the Maker’s Mark proof-lowering story to front-page news, prime-time TV’s lead, and the butt of jokes on late-night talk shows. All the while, brand fans felt betrayed and simply wanted to know why. Within eight days of lowering its proof, Maker’s Mark reversed its decision and enjoyed another week of prime-time coverage. Had the original move been a publicity stunt or just bad management?

We’ll likely never know, because Maker’s Mark and its parent company, Beam Suntory, treat the “proof debacle” (as they call it) like a hardened combat veteran treats the war: they just don’t talk about it. But it’s important to note that lowering proof helps stretch the product into more bottles, and fictitious backstories intrigue new consumers. Both have been going on since American whiskey became profit minded.

The whiskey business is not an altruistic industry run by choirboys. Distillers don’t take oaths of purity or do what’s in the best interest of their consumers. They do what they do to make money, and hyperbole and today’s marketing liberties are a part of this industry’s history. Bourbon folklore draws us in like Greek mythology, hooking us and making us interested in learning more. The fact that much of the spirit’s history is based on legends just makes for a better story, and it spices up the truth for a drinking culture that passionately wants information now—right or wrong.

There is no greater example of this than the Craig legend, which credits the minister with inventing bourbon around 1794.

The fact is, the term bourbon first appeared in print in 1821 in Bourbon County’s Western Citizen newspaper, where the Stout and Adams advertising firm promoted “bourbon whiskey by the barrel or keg.” Five years later, a Lexington, Kentucky, grocer wrote to distiller John Corlis to order more whiskey from “barrels burnt upon the inside, say only a 16th of an inch.”3 This is the earliest known reference of charring the insides of barrels in reference to whiskey.

But in all likelihood, distillers were charring barrels and using bourbon mashbills long before those references. In 1809’s The Practical Distiller, author Samuel M’Harry of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, suggests burning the inside of barrels to clean them and offers a whiskey grain recipe of two-thirds corn and one-third rye. M’Harry was quite fond of corn. “That corn has as much and as good whiskey as rye or any other grain. … Corn is always from one to two shillings per bushel cheaper than rye, and in many places much plentier.” If he had suggested this recipe be placed in a new charred oak barrel, he would have published a bourbon whiskey recipe.

Early Americans distilled whatever they could. In areas where grapes and other fruits were plentiful, they made brandy. In the New England area, they distilled molasses to create rum. Corn and rye were far cheaper and more plentiful than molasses and fruits, so that’s why these grains became the cornerstone for early American distillations. People love giving romantic stories about corn waving in the breeze and rye brushing against the distiller’s cheek, claiming that’s why corn became bourbon’s backbone, but that’s just a bunch of baloney. Much as the barrel-charring legend of Elijah Craig originated somewhere, the common legend about why distillers came to prefer corn is usually linked to the Corn Patch and Cabin Rights Act of 1776.

When Kentucky was still a part of Virginia, Virginians migrated there to raise the population in the soon-to-be state, as well as for land speculation. The Virginia legislature attempted to “regularize” Western lands and came up with the Corn Patch and Cabin Rights law, which allowed settlers to claim land if they built a cabin and planted corn in sections of Kentucky prior to January 1, 1778. But in their infinite wisdom, Virginia lawmakers failed to specify the cabin or corn patch size. Settlers planted three or four seeds of corn and built a small cabin with a few pieces of lumber, expecting to receive land. Thus, while it’s possible the Corn Patch and Cabin Rights Act helped a few distilling families establish themselves, the law was so “clumsy” and “unworkable”4 that it is likely to have had little impact at all on bourbon.

People distilled what they could to survive, trade, and get drunk. It’s really that simple. If settlers had found nothing but pinecones, there’s a good chance “America’s spirit” would be pinecone liquor, an ode to a summer breeze wafting through the towering pine trees.

Fortunately, corn, rye, and barley were harvested for whiskey, and distillers never toyed around with pinecone liquor. Or it never took off, anyway.

In times of corn overproduction, distilling the grain became a profitable venture for farmers and an eventual necessary savior to sagging grain prices. Although corn prices have fluctuated throughout American history, farmers know it’s a tried-and-true fact that people drink in good and bad economies. And that’s the real reason corn became the base of bourbon’s recipe: it grew.

WHO MADE THE FIRST BOURBON?

I believe some early Americans actually made what would qualify as bourbon but called it “corn brandy.” My friend and bourbon historian Mike Veach maintains an incredible bourbon collection for the Filson Historical Society, and in the diaries of two Frenchmen, brothers John and Louis Tarascon, Veach learned the brothers rectified white whiskey and sold it as corn brandy. It’s likely the Tarascons, who grew up near the Cognac region, brought the French brandy technique of charring barrels to whiskey aging. It’s certainly possible that they were also referring to the Swedish production of “corn brandy,” which was a spirit of mashed grain intentionally not completely rectified and diluted with water. Nineteenth-century connoisseurs said Swedish corn brandy was the “nearest approach” to making whiskey but was inferior.5 But given the fact that the Swedes’ version was largely isolated to their own region, it’s more plausible that the Frenchmen applied their country’s barrel-charring techniques and called the distilled spirit aged in barrels corn brandy. Brandy was what the French made, so they just aptly named the distilled corn spirit such. During the time, booze names were not as defined as they are today. There’s a good chance distilled potatoes were called whiskey, and people who thought they were drinking whiskey were really drinking vodka. Besides, most early American spirits were rectified to enhance the color. Rectifying meant adding prune juice, tobacco spit, rattlesnake heads and turpentine—you know, stuff that’s gross and will kill you—to make a clear spirit look more like aged whiskey.

Adding to the argument that the barrel-charring technique was created by the French, I’ve found bourbon’s aromatics to be similar to cognac’s nose, whereas bourbon and Scotch offer little to no taste or smell similarities. And bourbon whiskey is almost certainly named after a Frenchman. Well, kind of.

The two going theories about bourbon’s namesake are that it’s either named after Bourbon County in Kentucky or Bourbon Street in New Orleans. Both places were named after the Bourbons, the longtime ruling family of France. If you buy the Bourbon County theory, then you believe that early New Orleans merchants enjoyed the whiskey from barrels stamped “Limestone, Bourbon County, Kentucky.” Like the Craig legend, however, this one falls apart when you really analyze it: shipments from Kentucky to New Orleans took a year, and Veach writes, it is “therefore unlikely that there were enough whiskey shipments invoiced to Limestone to catch the attention of New Orleanians.”6 He suggests river travelers may have drunk aged whiskey on New Orleans’ Bourbon Street, and that’s where bourbon earned its name.

But the sad truth is we’ll likely never definitively know who truly invented bourbon or why he or she named it so.

Bourbon does not enjoy the centuries’ worth of historical research that beer and wine have commanded. Universities are only now taking bourbon history seriously, and the distilleries closely guard their true histories. Distillers owned slaves, ran whiskey during Prohibition, and used prostitutes for their marketing, and many of these connections still haunt bourbon’s ruling families. The Pogue family, for example, sold barrels to Cincinnati bootlegger George Remus during Prohibition. “Not a proud moment in our history, but some really neat history nonetheless,” Paul Pogue told me. That’s why legends and misnomers have permeated bourbon culture; the truth isn’t always pretty, and it certainly won’t sell whiskey. In fact, I surmise that early bourbon marketers promoted Elijah Craig and other legends to hide the unscrupulous truth.

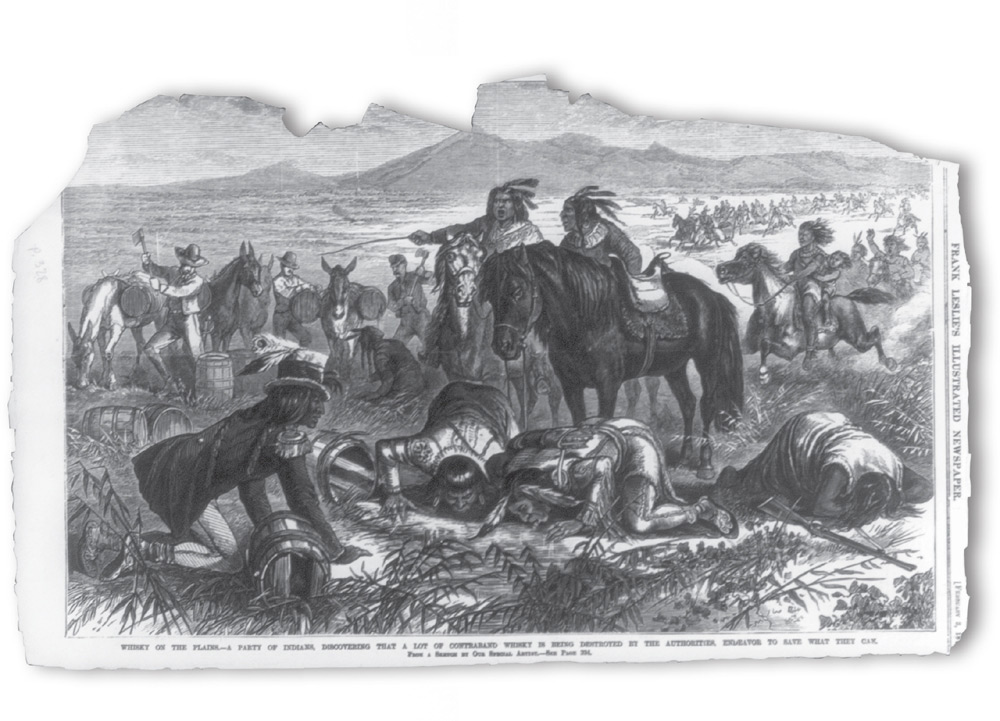

Many believe whiskey started the war between Native American tribes and the United States government. Whiskey traders took advantage of the tribes. In this drawing, published by Frank Leslie’s illustrated newspaper on February 3, 1872, Indians try to drink contraband whiskey destroyed by authorities. Library of Congress

For as long as traders have hitched their whiskey-filled wagons and tried to outsell the other guy, whiskey has been smack in the middle of unethical practices. Today’s folklore labels pale in comparison to the 1800s-era whiskey salesmen, who showed absolutely no signs of decency.

EARLY WHISKEY SALESMEN

When the United States was founded, settlers built relationships with Native American tribes, trading goods for fur pelts. You’ll find no shortage of literature condemning how this country acquired land from Indians. And right smack in the middle of this land grab was whiskey.

Settlers treasured furs, using them for shelter, wagons, clothing, and containers. Moreover, the huge international demand for beaver hats meant that furs were big business in the early modern global economy. Indians were at the center of this trade, as they essentially cornered the market on pelts by being the experts in their harvest. They, like all other peoples, developed a taste for whiskey. Traders took advantage of this desire for distilled spirits, getting their Native partners drunk and either trading for pelts far below their value or outright stealing them while the Indian traders were intoxicated. These whiskey traders often became the first white men that tribal leaders dealt with, and the traders sought to secure their influence with individual leaders as well as whole villages. “Each trader endeavors to impress the Indians with a belief that all other traders have no object but to cheat and deceive them, and that government intends taking away their lands by sending troops into their country,” wrote Colonel H. Atkinson, the commanding officer of the 6th Infantry Regiment, in 1819. “Hence the jealousy and distrust of the Indians towards government, and the bad opinion they have of whites for truth and honesty.”7

Whiskey crippled Indian nations, rendering them useless for hunts. It increased violence and often brought forth an unquenchable addiction that destroyed many lives.

Many agreed with Atkinson’s sentiment, arguing that early American whiskey traders destroyed potential peace talks with tribes. Colonel Clark W. Thompson, onetime superintendent of Indian Affairs in Saint Paul, Minnesota, believed the bloody war between the Sioux and United States began over whiskey. “I have made many and varied efforts to stop the sale of whiskey to the Indians. … The whiskey traffic is a great drawback to the welfare of Indians,” Thompson testified before Congress in 1862. “In my opinion, the whole Sioux nation was suddenly precipitated into a war with us through the influence of a little whiskey upon the brains of four Indians, for there is no evidence to show that it was a premeditated move.”8

By the 1880s, whiskey was both a tribal and a national epidemic, arguably started by unsavory traders looking to cheat Native Americans. The US government publicly blamed the whiskey trader as much as possible, perhaps to shield its own whiskey-distribution efforts and its removal and massacring of Native groups. Nonetheless, unethical white men were among the country’s first whiskey marketers. “These whiskey traffickers … seem to be void of all conscience, rob and murder many of the Indians,” wrote Richard W. Cummins, an Indian agent. “They will get them drunk, and then take their horses, guns or blankets off their backs, regardless of how quick they may freeze to death.” Cummins also called the trader “a dishonest man—a man that will condescend to the meanest of acts.”

They didn’t even have the decency to give Indians the good stuff. So-called Indian whiskey was defined as “Whiskey adulterated for sale to the Indians.”9 Traders added foul ingredients to whiskey sold to the tribes—in the Ozark Mountains of Arkansas, they made a special whiskey for Natives called the Redskin White Mule because of its destructive powers.

The shameful history of the whiskey traders illustrates why legends, not truth, became important in the marketing of bourbon. A historically accurate Indian whiskey-trader bourbon brand would be considered both racist and distasteful, and it would probably face boycotts, poor sales, and perhaps even failure.

Moreover, whiskey makers were often slave owners, which would also be problematic on a marketing label. Even President Thomas Jefferson worked with a contract distiller to make whiskey for his slaves, and President George Washington used seven slave distillers at his distillery. If a slave had “distiller” listed as one of his skills, plantation owners would spend top dollar to acquire him. In the despicable 1826–1827 slave catalogue Slave Trade: Slaves Imported, Exported, the author describes an unnamed slave as “a very well behaved man; a good distiller and a generally useful sort of person.” He then describes another man, who “was beaten by the driver” and “work[ed] as a distiller half the year.”10

Slavery is a conversation we tend to avoid as a nation; in whiskey, it’s a conversation distillers pray never comes up. At the Catherine Spears Frye Carpenter Distillery, whose 1818 recipe book contains the first known sour-mash whiskey recipe, the family owned several slaves, ranging in value and listed in the family’s account books as “taxable property.”

The fact is, bourbon is mostly made in Kentucky, and prior to the Civil War the Bluegrass State was a major slave state. The famous distiller E. H. Taylor was the son of a major slave trader. When Kentucky became a state in 1792, 23 percent of the state’s households kept slaves.11

Slavery is this country’s burden to bear, and early whiskey makers took part in this shameful act. Just like an Indian-trader whiskey label, you will not find slave whiskey labels anytime soon, but like Indians, slaves are very much a part of early American whiskey. Slaves’ full contributions to American whiskey may never be known, but I surmise they created many of this country’s first whiskeys. The fact that slave-selling guides placed a premium on distillation as a skill shows that slave distillers were obviously highly sought after; it’s a shame we’ll never know their true part in the development of bourbon. Yet in every bourbon legend, the mention of slavery is conspicuously absent.

You will, however, find modern whiskey labels celebrating a felony sport. American whiskey and cockfighting, the bloody death match between two roosters, have long had a strong connection. Both grew in popularity in the 1800s. Watching two roosters disembowel one another was considered one heckuva a good time, and this led to early American whiskey companies both depicting cockfighting in their advertisements and naming brands after famous cocks. The use of cocks in a whiskey brand was so popular that start-up brands tried to imitate successful ones. In the late 1800s, US courts determined that the name of Miller’s Game Cock Whiskey infringed upon the trademark of a separately owned Miller’s Chicken Cock Whiskey. The landmark case said the use of “Chicken” instead of “Game” created confusion.

Today, cock labels confuse nobody and incite chuckles for their innuendo. When contemporary labels Chicken Cock Whiskey and One Foot Cock Whiskey were launched in recent years, frat boys everywhere ran to the liquor stores and purchased them for gag gifts and laughs. But those two whiskeys are barely worthy of a fraternity’s toilet bowl. On the other hand, Fighting Cock Kentucky Straight Bourbon Whiskey is one of the greatest values in all of whiskey. The six-year-old bourbon label depicts a rooster in full attack mode, its razor-sharp talons prepared to slice open its unlucky foe.

Cockfighting holds a strong tradition in whiskey-making areas, and I imagine there are still quite a few illegal cockfighting rings in illicit moonshine country. But this particular label likely appeals to old-school farmers. I certainly cannot see an animal rights activist buying Fighting Cock. No group has made a large-scale attack about its label or meaning, but bourbon is generally trying to move away from this hillbilly and farmer look in an effort to appeal to younger, city-dwelling folk. Cock labels will remain a novelty.

What will never go away in American whiskey is the rectifier, a dirty word in many circles, who mixes distillations or aged whiskey with various compounds. Many famous whiskey names operated under rectifier licenses: George Garvin Brown, founder of Brown-Forman, and brand namesake W. L. Weller were both rectifiers. In the 1800s, rectifier companies largely owned the bourbon market and operated in downtown Louisville, Kentucky, on a strip called “Whiskey Row.” They purchased bourbon whiskey from distillers and blended the bourbon with clear grain spirits and added coloring. In 1896, a congressional committee concluded that distillers sold the majority of straight bourbon to rectifiers instead of consumers.12 In turn, the rectifiers diluted the straight whiskey and sold it.

All the while, in the 1800s, taverns and saloons purchased barrels of whiskey direct from the wholesaler. Much like the rectifiers, the tavern owners wanted to earn a lofty profit, so they added a few choice ingredients to the barrel of whiskey to make it last longer. For some reason, tobacco juice was a prime additive. Perhaps it added decent coloring, but can you imagine ordering a shot of whiskey and half it being tobacco spit? Suffice it to say, many consumers were getting sick from bad whiskey, and the country had a serious issue on its hands—consumers needed protection.

In 1897, Congress passed the Bottled-in-Bond Act to ensure consumers received a good product. At the time, whiskey distillers typically did not bottle their own products. They sold barrels of whiskey to wholesalers, who bottled it. This act became the first piece of consumer protection legislation in American history and gave the power to the distillery companies versus the rectifiers.

The Bottled-in-Bond Act of 1897 not only gave consumers confidence in the country’s bourbon, it also gave women career opportunities. Women became the chief bottling-line operators because they were considered to be more coordinated than men and to break fewer bottles. Oscar Getz Museum of Whiskey

These days, rectifiers are another bane of American whiskey history. The sheer thought of adding grain spirits to bourbon is enough to make aficionados like myself want to gag. But rectifier licenses still exist. Kentucky’s Alcoholic Beverage Control Laws define a modern rectifier thusly: “The license authorizes the licensee to purify or refine distilled spirits and wine. The holder of a rectifier’s license may purchase from distillers.” Many major brands operate under rectifier licenses, including Jefferson’s and Old Rip Van Winkle, because they don’t own distilleries. Instead of adding caramel coloring, however, today’s bourbon rectifiers mingle barrels of bourbon from the same or different distilleries. They don’t place the word rectifier on the label, though, because nobody would buy their products.

On the other hand, a large chunk of consumers would probably purchase sexually suggestive labels that pay homage to another set of whiskey salesmen, or rather saleswomen—prostitutes. US brothels were major whiskey retailers in the 1800s. In my book Whiskey Women: The Untold Story of How Women Saved Bourbon, Scotch, and Irish Whiskey, I argue that prostitutes were as important as fur traders in introducing whiskey to new markets. In an 1857 physician-led survey in New York City, brothels reported selling $2.08 million in wine and liquor and $3.1 million in sex. This brothel tie to whiskey was so strong that Old Crow bourbon created ads in the 1870s depicting one prostitute dancing while another watched from a seductive chair pose.

This connection to prostitution, however, made bourbon vulnerable to the leaders of the temperance movement, who called whiskey a societal problem. Men left their families for drink and sex. Temperance crusaders used the Old Crow advertisements as a recruitment tool. Around the same time, they also began questioning the medicinal uses of whiskey.

Major medical journals, including the New England Journal of Medicine, studied whiskey’s efficacy. On treating scarlet fever, Dr. Samuel George Baker wrote in 1839, “I have been greatly pleased to see the delightful effects of the whiskey ablution. Immediately after it is used, [the patient] falls into a sweet sleep.” For treating pneumonia, The Present Treatment of Disease instructed in 1891, “If the case passes into the stage of general exhaustion, give whiskey freely.”

Despite legitimate medical support, a handful of whiskey makers overstepped their bounds, making unsubstantiated claims. Duffy’s Pure Malt Whiskey claimed to cure just about every imaginable disease, including consumption and cancer. Temperance leaders exploited these false claims in their quest to stop the flow of alcohol. In her memoir, the axe-wielding Woman’s Christian Temperance Union personality Carrie Nation wrote: “Any physician that will prescribe whiskey or alcohol as a medicine is either a fool or a knave. A fool because he does not understand his business, for even saying that alcohol does arouse the action of the heart, there are medicines that will do that and will not produce the fatal results of alcoholism, which is the worst of all diseases. He is a knave because his practice is a matter of getting a case, and a fee at the same time, like a machine agent who breaks the machine to get the job of mending it. Alcohol destroys the normal condition of all the functions of the body.”

By the time Nation published her book in 1908, the government had taken steps to stop false claims. The Bottled-in-Bond Act of 1897 gave consumers confidence that a bottle bearing the “bottled-in-bond” label was safe to drink and not diluted with unwanted contaminants, and the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 put an end to snake-oil salesmen’s false claims of curing diseases. Meanwhile, the American Medical Association instructed its membership to be more cautious of medicinal whiskey claims and to boycott medical journals carrying Duffy’s Pure Malt Whiskey advertisements.

As politicians debated Prohibition in the 1910s, temperance-minded lawmakers could choose from any number of whiskey-related reasons why alcohol should be banned. Going into Prohibition, American whiskey had already had its share of nasty history; it was made by slaves and sold by unsavory traders and prostitutes, it had caused presidential scandals, and it had likely led to thousands of deaths through false advertising and rectifying. Maybe legends are not such a bad idea for selling bourbon, after all.

GOVERNMENT AND BUSINESS INTERFERENCE

When Prohibition was ratified January 16, 1919, the bourbon industry was decimated, but it survived thanks to the medicinal market. Nearly a decade before the discovery of penicillin, doctors still prescribed whiskey despite the so-called disease of “whiskey liver” and the medical community’s overall mood change toward whiskey prescriptions. Nonetheless, people were sick a lot during Prohibition and doctors happily prescribed whiskey … for medicinal usage only, of course.

Six companies received medicinal licenses to sell 100-proof bonded spirits: the American Medicinal Spirits Company (later named National Distillers), James Thompson and Brother (renamed Glenmore Distillery), Brown-Forman Distillery, Frankfort Distilleries, A. Ph. Stitzel Distillery, and Schenley Distillers Corporation (part of which is now Buffalo Trace). These six medicinal license holders went through their whiskey stocks rather quickly. In 1928, in what’s known as the “Distillers Holiday,” the government allowed one hundred days of distilling to create more than three million gallons of medicinal whiskey. Distilling permits were also granted in 1930, 1931, 1932, and 1933.

When Congress ratified the Twenty-First Amendment on December 5, 1933, bourbon distillers were back in business. Companies made large investments, knowing the country wanted a stiff drink of fine bourbon. Family businesses were staking their life’s work and heritage to the late 1930s Bourbon Boom.

Among these were the Blairs, an important Kentucky whiskey family. In 1876, Thomas C. Blair founded the Blair Distilling Company, built in the limestone hills of Chicago, Kentucky, near the Louisville and Nashville Railroad line. The Blairs were highly reputable straight bourbon whiskey distillers, producing about 1,200 barrels a year. After Prohibition, Thomas’ son, Nicholas O. Blair, pushed all the family money to the middle of the table and went all in. He learned how to distill from his father and designed a large copper still; then he built two unique gable warehouses that optimized airflow. Blair said his warehouses made ideal bonded whiskey. He made Thixton-Millett, Old Boone, Thixton’s Club Special, Thixton’s V.O., and Mel Millett. In addition to making his own bourbons, Blair contract-distilled the Old Saxon bourbon for D. Sachs & Sons of Louisville.

In the late 1930s, small to midsize distilleries like Blair’s were popping up all over Kentucky. There was a Churchill Downs Distillery at Smith’s Switch near Boston, Hoffman Distillery and Old Joe Distillery in Lawrenceburg, the General Distillers Corporation in Louisville, and Cummins Distilleries in Athertonville. Large distilleries had offices all over the country, while the smaller ones looked to bolster capacity.

Because Kentucky bourbon meant jobs, everything about the industry was newsworthy. The Kentucky Standard, February 17, 1938, wrote, “The first whiskey made in Nelson County since the repeal of Prohibition, will be bottled in bond by the Bardstown Distillery about March 1. … The whiskey will reach its four-year-age Monday, February 21.”

The Blair Distilling Company was a victim of World War II. Grain sanctions kept the Blairs from receiving corn for whiskey, and they went out of business. Old Boone was one of its labels. Like many distilleries, Blair had high hopes coming out of Prohibition.

Then, Germany invaded Poland in 1939, and bourbon producers once again found themselves at the mercy of US lawmakers. This time, instead of an outright booze ban, the government sought the assistance of distillers. President Franklin D. Roosevelt formed a whiskey council made up of industry executives to help the government create a distillery plan for the war effort. The Kentucky bourbon distilleries made industrialized alcohol at roughly 190 proof. Since bourbon stills could not reach this high a proof, the stills had to be modified. Distillers added collar columns, applied greater pressure, and reached higher temperatures during distillation. The alcohol never touched oak and would have been shipped immediately to a facility for eventual use in creating grenades, jeeps, parachutes, and other essential war materials.

The distillery community frequently requested distilling holidays, but the government steadfastly denied such requests, wanting instead to stockpile industrial alcohol and reserve grain usage for the war effort. According to a September 1943 Associated Press wire report: “The question of permitting resumption of whiskey output long has been a ‘hot potato,’ with no official anxious to risk the criticism, which might result from the diversion of grain into whiskey-making at a time of a possible food shortage.”14

The whiskey brands with corporate backing survived World War II, but many family-owned businesses closed their doors, and many others barely stumbled out of the 1940s. The Blair Distilling Company was one of the casualties. Schenley purchased many smaller distilleries for their equipment and whiskey stocks. The 1950s and 1960s would be a time of corporate growth, making stellar whiskey, and buying up the small producers.

The big names of the era were the Seagram Company, Glencoe, Brown-Forman, Glenmore, Schenley, and National Distillers—conglomerates that were publicly traded or had interests outside of bourbon. These six would buy and sell brands for the next forty years, yet only Brown-Forman still exists as a company. The other five companies sealed their fates with bad business decisions, some of which circled around investing too much in bourbon when it was going out of fashion.

For example, in 1961, the Barton Distillery in Bardstown, Kentucky, expanded its plant at a cost of $750,000 and added state-of-the-art filtration systems, fire protection equipment, and new warehouses, giving the distillery a total of twenty-eight aging warehouses. This made it the largest distillery at the time. They picked up a $12 million loan, registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to become publicly traded with 360,000 common stock shares and filled more than 1 million barrels following Prohibition. But the younger crowd didn’t drink bourbon—that’s what their parents drank. They wanted vodka.

Five years after Barton’s significant risk, its bourbons, especially Barton Reserve and Kentucky Gentleman, were hemorrhaging money. According to the company’s 1966 corporate report, Kentucky Gentleman was down fifty-four thousand case sales after spending $124,000 in advertising on the brand. A diverse portfolio kept Barton in the black, but the sagging bourbon economy led to less enthusiasm toward production and deteriorated outside investment interests.

I consider this twenty-year stretch a dark time in bourbon history. We saw the closure of the Old Taylor Distillery and the selling of Stitzel-Weller Distillery to Norton-Simon in 1972. The conglomerate companies executed strategies that still leave spirits business execs scratching their heads, such as Seagram’s taking Four Roses bourbon off American shelves and only making it available in foreign markets.

Fortunately, the bourbon makers of the time were producing some of the best whiskey ever made. Today, 1950s- to 1970s-era bourbons are highly coveted by collectors. (In the next chapter, I explain why this era’s whiskey is different from today’s.) There were a few bright spots during the down times, as well: Maker’s Mark, a relatively new brand, established itself as the first ultrapremium bourbon, while Jim Beam created a cult following with its decanter series. In 1984, George T. Stagg Distillery’s master distiller, Elmer T. Lee, launched the first single barrel commercially available to consumers. Called “Blanton’s,” after Lee’s former boss, the bourbon changed the industry and was followed by others. Four years later, Jim Beam’s Booker Noe popularized the small-batch method, in which he mingled honey barrels together and created bourbon perfection.

When Woodford Reserve launched in 1996, the distillery, once home to James C. Crow and Oscar Pepper, gave bourbon a much-needed tourism spark. The distillery became a picturesque vacation spot for tourists from around the world.

The 1990s was a single-barrel and small-batch race for companies that had strong bourbon intentions, while some Scotch- and clear spirits–leaning companies downsized their bourbon operations. Brown-Forman opened the Woodford Reserve Distillery in 1996, while United Distillers, which acquired Norton-Simon (now Diageo), closed Stitzel-Weller in 1992. If United Distiller executives had known that the Stitzel-Weller stills churned out whiskey used in the legendary Pappy Van Winkle line, I wonder whether they’d have stopped making whiskey there. The Kentucky Bourbon Festival, Kentucky Bourbon Trail, Whisky Advocate, Whisky magazine, bourbon blogs, bourbon forums, and hundreds of bourbon-improving experimentations launched in the 1990s, leading to a new millennium that would become bourbon’s greatest fifteen-year stretch in history.

Today, you can find limited-edition bourbons that are as close to perfect as possible, as well as value bourbons under thirty dollars that don’t break the bank and are every bit as good—for one or two seconds—as the limited editions. But as a consumer, all this bounty can make it hard to select bourbons for your unique palate.

Unlike wine, for which grape percentages are disclosed and terroir implied through the industry’s Area of Control designations, bourbon uses its label space for backstories and falsehoods. Although I concur that bourbon legends grew out of necessity, these traditional marketing methods put consumers at a disadvantage for selecting bourbons they like. As Ed Foote, the former master distiller of Stitzel-Weller, once told me, “Whiskey distillers are full of shit.” Foote especially takes issue with backstories related to yeast: “You mean to tell me that somebody’s grandpappy carried the family yeast recipe from Cromwell to America?” Foote’s career started in the early 1960s and ended in the late 1990s, and he’s heard a lot of stories about yeast. Take a look at this 1957 Old Charter bourbon advertisement:

How do you maintain the integrity of a bourbon’s flavor … keep it unvarying through the years. The man behind Old Charter’s answer is to hold fast to the traditions of making fine bourbon. The yeast he uses, for example, is a pedigree strain. It was developed away back in 1898. Every batch of Old Charter is made with cells from this master strain. And every bottle bears its imprint—a uniquely mellow bourbon flavor. He’s gone to a lot of trouble to coddle this strain of yeast for 59 years. He went to even more trouble to preserve it in Canada for 14 prohibition years. But the man behind Old Charter tolerates no short cuts. No short cuts in the aging, either. This bourbon isn’t hurriedly dripped through charcoal beds. Nor is it double-timed through a barrel. It is charcoal-mellowed the slow way—or seven long years in charred barrels of oak. And so it goes through every step in making Old Charter. It is by any test a costly way to make bourbon. But then, what is the price of perfection? When you drink Old Charter, you mark yourself as a man who appreciates the finest Kentucky has to offer in bourbon. When you serve it to your guests, you offer them a compliment on the esteem in which you hold them.

However, prior to 1920, no dry yeast of suitable stability and with a fermentation rate comparable to that of fresh yeast “had been established.”15 The commercial development of active dry yeast did not occur until World War II, and industrial refrigeration likely was not applied to yeast in Old Charter’s 1898 development. Distillers would keep their wet yeast in cool places, but it’s impossible to know if the yeast remained pure and without mutation. So the original Old Charter’s yeast story that was sold to consumers in 1957 was a long stretch. While this company certainly handled its yeast with absolute care, it’s doubtful they maintained the exact same yeast from the 1800s.

Much like Old Charter’s yeast story, non-distillery-owning bottlers have been playing it loose with the truth since bottling bourbon became mainstream. Another example is Chapin & Gore bourbon, which was owned by McKesson & Robbins. The company purchased bulk whiskey from the Fairfield Distillery in Bardstown, Kentucky. Like many NDPs today, McKesson & Robbins, which sold the brand to Schenley distillers in the 1940s, offered a lot of BS on its labels and in its advertising:

In the west of the 1850s, Jim Gore’s adventurous life early taught him the importance of being careful in any undertaking. His horse, his gun, his friends—all had to be best in the world. Small wonder, then, that the famous Kentucky bourbon he originated in later years was called “Old Jim Gore—Best in the World.” Old Jim Gore Bourbon Whiskey is again available after years of careful preparation to exactly duplicate the three point formula that Old Jim, him self set down: Must be genuine Kentucky Sour Mash; Must be made with “aplenty of costly, small grain—for richer flavor; and must be slowly distilled carefully to make it extra light.”

In other advertisements, McKesson & Robbins marketing team later said Jim Gore invented the term sour mash.

If McKesson attempted such a claim today, whiskey geeks would tear the company to pieces on Facebook, Twitter, and blogs. Heck, the New York Times might even take a stab at it, because it hasn’t exactly been a reputable company. In 1938, the SEC determined its books were cooked, missing $20 million of the $87 million of the company’s assets. The SEC created new regulations based on the McKesson & Robbins scandal, but from a whiskey perspective, they were no different than any other company.

They stretched Chapin & Gore’s truth as much as they could, and they were likely buying whiskey from several distilleries. In fact, selling bulk whiskey has always been a profitable venture for bourbon distillers. In 1966, the Barton Distillery sold $2.45 million in bulk whiskey to undisclosed companies, earning a $653,740 profit. These could have been other distillers needing additional whiskey to meet demand or bottlers selling a phony backstory, but offering whiskey stocks to competitors and bottlers is a storied business practice in American whiskey. It still happens today and is how many companies made it through lean times.

The interesting difference between the NDPs of yesterday and today is that the contemporary companies hold back on marketing the grains and distilling methods. In fact, many modern bourbon producers avoid marketing on these and their aging techniques, while many distilleries refuse to share mashbills.

Just take a look at all the bourbons on shelves today. You see stories on the back labels and clever marketing words like smoothest, best, and award-winning. What you don’t see are mashbills, char levels, grain origins, true water sources, distillation techniques, entry proof into the barrel, or other production information. In recent years, there’s been a small whiskey geek movement to out distillers’ recipes and demand transparency. But just as bourbon folklore was born, bourbon secrecy stems from protective measures to thwart lawsuits and copycats. When Diageo launched the fourth release of its Orphan Barrel Project, it disclosed that the whiskey originated from the George T. Stagg Distillery in the early 1990s. Sazerac, the trademark holders of Stagg and owners of the actual distillery, questioned this use of the Stagg name, saying, “Diageo is attempting to trade on our reputation.” After this shot across the bow, hardcore bourbon consumers knew the cold truth: genuine transparency may never happen in their beloved spirit category. If NDP Johnny Distiller buys five hundred barrels of bourbon at Distillery X, which doesn’t want this fact known, why would Johnny risk litigation to disclose where their whiskey came from?

By today’s standards, the popular bourbon Chapin & Gore would be considered a non-distiller producer, meaning one that buys and bottles whiskey somebody else has made. Back in the 1950s, however, consumers didn’t seem to care where the whiskey was produced. What changed? Visitor centers and the Internet didn’t exist then.

Bourbon’s only true chance with transparency lies with the big distillers—1792 Barton, Brown-Forman (Old Forester and Woodford Reserve), Buffalo Trace, Four Roses, Heaven Hill, Jim Beam, Maker’s Mark and Wild Turkey. They make the bulk of this country’s bourbon and choose to hide or share ingredient information.

There are a few brands that are transparent about their whiskey’s origins. For the most part, though, bourbon brands are selling the name on the bottle first and what’s inside second. Bourbon’s brand names are the tapestry of legends, truth, and contemporary characters that enticed me to become a bourbon writer. Yes, I love every taste profile of bourbon, but I fell in love with the folksy stories and the real histories on the labels. The true brand stories are as interesting as the myths.

It’s time to break out of the bourbon history and regulation mold and get to what’s really important—what’s inside the bottle. After all, if bourbon didn’t win over palates, nobody would care about the history.