7 Constructivism, computational social-relational methods, and multiple correspondence analysis

David M. McCourt

Introduction

Computational social science is increasingly prominent in top tier journals, skills training, and hiring decisions – especially, though not exclusively, in the US academy. In this chapter, I urge constructivists not to give in to an impulse to reject computational social science as something constructivists don’t do, and to consider what such techniques might have to offer. While much computational social science does not mesh with the constructivist concern with the intersubjective meanings and social facts that make up the socially constructed world, constructivists should be wary of the common misconception that they cannot and should not adopt computational techniques (see Jackson 2011, 201–7; Barkin and Sjoberg forthcoming).

In the spirit of the volume, I illustrate with my own engagements with a method known as Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA). MCA is a subset of Geometric Data Analysis (GDA), an approach gaining popularity in political sociology (Buhlmann, Davis and Mach 2012; Denord et. al. 2011; Flemmen 2012; Laurison 2011; Lebaron 2001; Prieur et al. 2008). MCA’s principal value is its ability to analyze and graphically represent the sorts of social spaces IR constructivists see as central to political life (e.g. Pouliot 2016, 227–33). While I focus on MCA, the argument extends to other computational methods, like text and content analysis using NVivo and other such applications.

Like the other contributions, I begin with a reflection on Constructivism’s typical relationship to methods, which might prevent engagement with new computational techniques, which forms part of a broader reflection on what Constructivism is and could be in IR (McCourt 2016a, 2016b; see also Steele 2017; Subotic 2017; Hayes 2017). The bulk of the chapter is spent on expression – introducing MCA, illustrating its potential, and addressing some practical questions of research design. Finally, I discuss MCA as tactic – who might benefit from engaging MCA? To be clear, MCA will not be for everyone, nor even the majority. It should be especially attractive, however, to junior scholars who want to converse with the mainstream of US political science. The chapter is primarily targeted at them.

Reflection: becoming a Constructivism user

Unlike sociologist Howard Becker (1953), who famously became a marijuana user for research, I was a constructivist from IR ‘birth’. My doctoral supervisor was an early constructivist, Friedrich Kratochwil, so I was unlikely to become a realist or rationalist. Other constructivists likely feel similarly – either because they are on the constructivist ‘family tree’ or because Constructivism had become by the early 2000s an attractive theoretical approach to adopt.

Being born a constructivist came with rather opaque instructions when it came to methods, however – about how to do Constructivism. Methods training varies widely and generalizing is difficult. But my suspicion is that other constructivists might have had a similar experience to mine: a combination of some exposure to ‘interpretive’ political science methods and some Ludwig Wittgenstein and J.L. Austin. The result has been an ongoing reflection about how to do Constructivism properly, a search which spans both methods writing in IR and political science, but also philosophy and social theory on the nature of knowledge, action, and science itself. Again, I would be surprised if my experience is unique; in simple terms, while many political scientists read the Stata manual, many constructivists read philosophy.

Following Patrick Jackson (2011, 201–7), much of the reason is that Constructivism entails no specific methodological commitments. Constructivism is a claim about the nature of reality: that it is made up of individuals creating the meaning of their shared world(s) through their associations. The upshot is that Constructivism is a meaningless category in terms of methods. The method/methodology distinction made by Jackson (2011) helpfully distinguishes between specific techniques, like statistical analysis, and the broader accounts we hold about how knowledge is made. Again, Constructivism is a claim about reality, not the general or specific ways in which it should be studied. It follows that there is no good philosophical reason that Constructivism should be understood as requiring a ‘qualitative’ or ‘interpretive’ approach at the level of method – even though we may have been taught it that way.

Why then is Constructivism seen as a qualitative/interpretive approach? The typical answer is that because meaning is principally conveyed through language, constructivist research tends to focus on interpreting meanings through things like speeches, interviews, strategy documents, oral histories and memoirs. Consequently, constructivist research tends to be in the form of prose where such meanings are quoted to back up assertions that some particular actor understood a situation in a postulated way and acted accordingly, thus explaining (or allowing us to understand, if the term explanation is rejected) that action.

However, there is more to the equation of Constructivism with so-called interpretive methods than this. Part of the issue is that constructivist scholars who want to engage with other mainstream approaches are forced to speak the language of science. The rise of terms like process-tracing and discourse analysis can in this sense be explained by the anxiety around naming what constructivist scholars do to give it some legitimacy in the eyes of proponents of more naturalistic methods.

Less commonly discussed is the extent to which the choice to become a constructivist is a reflection of the position of researchers in the field of IR, such that scholars with less social capital, and those at lower ranked institutions, are (self-) selected into Constructivism. Sociologist Andrew Abbott (2001, 69) argues that Constructivism is a weapon of the weak, “often employed by those who lack certain kinds of knowledge resources: young people who lack senior positions, researchers lacking money to do expensive kinds of work, outsiders attacking culturally authoritative definitions of social phenomena, amateurs who lack certain kinds of technical skills.”

Abbott’s is an unpleasant assertion, and would need to be proven rather than asserted. But the point is that there may well be social forces that lead some junior scholars to adopt Constructivism and others to reject it. One of these, certainly, is that new researchers interested in specializing in IR often choose quickly whether to do quantitative work or react strongly against it, becoming de facto constructivists. (Beyond the US, the choice is different, but since the term emerged and still makes more sense in the US, I need not elaborate further here (see McCourt 2016a)).

Constructivism, then, is by nature less a coherent theoretical approach than a space for doing IR that is different to the mainstream within US political science in that it is more sensitive to social, cultural and historical context (McCourt 2016a, 481–2). Both theoretically and methodologically, therefore, constructivists in the US academy fight on the terrain of others. Yet rather than decry this state of affairs, constructivists should to embrace it. To see why, we should turn to sociologist C. Wright Mills.

Constructivism as classic social analysis

Mills’ The Sociological Imagination (2000 [1959]) is foundational for any trainee sociologist, but given the affinities between Constructivism and sociology, Mills has much to offer IR constructivists too. The main take homes are these: if we accept that (1) IR Constructivism is a form of what Mills terms classic social analysis, then (2) we can also accept that each scholar should be their own methodologist, designing methods to fit problems rather than restricting themselves to standard methods. Constructivists can and should look far and wide for techniques and methods that help them analyze the social construction of world politics.

By classic social analysis, Mills means a tradition that includes such thinkers as Herbert Spencer, August Comte, Emile Durkheim, Karl Mannheim, Karl Marx and Max Weber. As Ruggie (1998, 857–62) has shown, Constructivism had its antecedents primarily in Durkheim and Weber. Tellingly, bringing Mills’ list up to date would have to include Michel Foucault and Anthony Giddens (both influences on early constructivists, e.g. Onuf 1989; Wendt 1992) and Pierre Bourdieu and Charles Tilly (each influential in recent Constructivism, e.g. Pouliot 2011; Nexon 2009). I am not then the first to point out the affinities between Constructivism and classic social analysis (see also Justin Rosenberg (1994) on the “international imagination”).

The case for viewing Constructivism as classic-social-analysis-in-IR need not be pressed. Its usefulness is to set up the argument that Constructivism understood as a space within US IR and political science for doing something different from the mainstream, is a positive condition (see also Rosenberg 2016). As heirs to classic social analysis, the type of knowledge aimed at by constructivists is different from the timeless, general, abstract and context-free knowledge aimed at by the scientistic mainstream. As Friedrich Kratochwil (2006) in particular has stressed, Constructivism is problem-driven and attuned to the practical and not merely theoretical nature of political knowledge. The consequence is that questions of method – of what counts as data or evidence – cannot be determined before research is designed. Indeed, deciding of what something is a case and therefore what counts as evidence is always part of the challenge.

As such, a second important implication follows. As Mills noted (2000 [1959]: 121), “every working social scientist has to be his [sic] own methodologist and his own theorist, which means only that he must be an intellectual craftsman.” The constructivist should resist, therefore, adopting wholesale available methodologies or methods, and must craft their own depending on the question at hand. The rise of interpretivism in political science, although a welcome development in many respects, should not then be seen to exhaust the types of methods a constructivist can deploy.

Where, it might be asked, does this leave methods training? For Mills (2000 [1959], 121), the type of course graduate students take in regression analysis, for example, has value: “Every craftsman can of course learn something from over-all attempts to codify methods.” But he cautions that what such courses convey is “often not much more than a general kind of awareness. That is why ‘crash programs’ are not likely to help social science develop.” Mills further warns “The Methodologist” to “[a]void the fetishism of method and technique” (2000 [1959], 224). In the rest of the chapter, therefore, I offer an overview of – rather than a crash course in, and still less a fetishization of – one technique constructivists might find useful in their research: Multiple Correspondence Analysis.

Expression: multiple correspondence analysis

The foregoing reflection suggests that constructivists are not limited to a narrow form of research design centered on interpretive methods; this is not to say that interpretive methods are inappropriate, only that Constructivism is a broader tent than commonly recognized. To give an illustration from my own work, my previous research on UK foreign policy since 1945 aimed to shift Constructivism away from the notion of identity toward the more relational and processual concept of social role (McCourt 2014). I showed how in repeated interactions between Britain and the US and France, Britain was constructed as a residual great power. While I believe the account is persuasive, I came to realize it lacks a sense of the wider world of UK foreign policy – the people who have done the constructing of Britain’s role in the world: diplomats, policymakers, think tank analysts, even IR scholars (see McCourt 2011). Who are they? How do they come to speak authoritatively in the struggle over UK foreign policy? In the wake of Brexit, these questions have become even more pertinent, as a domestic discourse of national sovereignty pushed aside a long-standing and powerful discourse of great power politics. In designing a new study, I am exploring ways to pose and answer these questions. Multiple Correspondence Analysis is one way.

The following introduction does not aim to show the reader how to use MCA, but rather to introduce MCA’s logic, show how it meshes with a constructivist perspective, and ideally convince readers to investigate further. For further technical instruction, the reader should see Greenacre and Blasius 1994; Grenfell and Lebaron 2014; Le Roux and Rouanet 2004.

Multiple correspondence analysis: the basics

MCA is a form of geometric data analysis (GDA) that can be used to construct a graphical representation of a social space – like the worlds of foreign policy-making noted above, or the social space of diplomats at the UN recently analyzed by Pouliot (2016). A statistical technique, MCA takes a dataset of information about a set of actors, whether individuals or groups, and uncovers the latent relationships between them. A dataset analyzed might include biographical data such as age, race, gender, nationality, education level, earnings and level of experience, if the actor is an individual, to organizational data on the size and makeup of organizations. Data might also cover subjective information, such as personal tastes, habits, opinions, or policy preferences, again both for individuals and groups. Using either R or a software package called SPAD, MCA then measures the degree of social distance between the actors in the dataset on the basis of their information. Two female individuals aged 30 with the same level of education and earnings have a social distance of 0 from one another; two individuals of varying characteristics on these variables move further toward a social distance of 1. By measuring such distance across multiple variables, MCA identifies the principal axes of difference and thus uncovers the structure of a social space. MCA then displays that structure graphically as an aide to interpretation.

There are two tendencies when it comes to the use of graphical and mathematical techniques we need to be wary of if we are to understand what is distinct and therefore powerful about MCA, and its affinities with Constructivism. The first tendency is to assume that statistics covers only methods that search for probability – in other words, that the aim in statistical social science is to sample from a population to find the probability that two variables (the independent and the dependent) are sufficiently correlated to make causal claims about the relationship. For the creators of GDA, the equation of statistics with probability is incorrect, as statistics is not in the first instance about the discovery of probable relationships in a dataset but actual ones. The conflation of statistics and probability still characterizes much of the academic study of statistics, but proponents of a geometric approach, which originated in France (on the historical development of MCA, see van Meter et al. 1994.), have developed a set of approaches that have a different – geometric – conception of statistics that now occupy a clear niche within the broader statistics field.

Here long-standing debates in the philosophy of social science raise their heads: disagreements about the nature of explanation and causal inference, and the difference between explanation and interpretation. These debates need not be rehashed here. What must be highlighted is the distinction between regression analysis and geometric analysis. Whereas standard regression analysis is quantitative (i.e. the data analyzed is in numerical form), driven by standard matrix procedures (e.g. multiplication, division), and sampling oriented, the logic underpinning MCA is geometric or spatial, formal (i.e. mathematical procedures are guided by the geometric structures uncovered, not the other way around), and description-oriented (Le Roux and Rouanet 2004, 6). These distinctions underpin the affinities between geometric data analysis and Constructivism.

First, like Constructivism, MCA is inductive rather than deductive. Is it the case, for example, that the social space of foreign policy-making is split into two, between insiders with certain characteristics, and outsiders with other characteristics? Or is it divided in different ways? Which views and dispositions of foreign policymakers actually go together? Whereas standard statistics tries to uncover the likelihood of, say, social class, age, or party affiliation correlating with hawkishness, from a sample to a population – which is always tricky in the small-N world of international politics, leading to often meaningless inferences – MCA describes the actual relations between individuals in a population, in terms of what makes them similar and different.

The second, related, tendency to be wary of is to read graphs as a mode of data presentation, rather than as an aide to the interpretation of data. In simple terms, we tend to assume that information presented in a graph can be read off by looking at where points fall along the graph’s axes, where axes measure certain things (age, GDP, percentage of a given measure, etc.). By contrast, the graphs produced by MCA are a guide to interpretation, and the points’ location on an axis does not correspond to absolute values of anything. The axes on MCA graphs represent the amount of the overall variance in a dataset that is captured by two axes of differentiation. What the axes represent, then, is precisely what has to be interpreted.

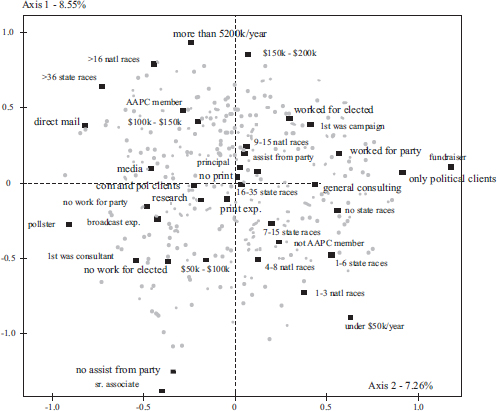

An MCA has two principal graphical outputs: a so-called ‘cloud of individuals’, which plots on a series of 2D spaces each individual in a dataset in terms of their relations to every other individual; and a ‘cloud of categories’, which plots the variables put into the dataset, such as education level – e.g. Ph.D. – or age. The axes on Figure 7.1 thus do not do what axes on graphs typically do – display known characteristics, such as age, wealth, sex, plotted against the individuals with those characteristics. Rather, the axes represent the amount of difference captured by the social distinction the MCA has uncovered (the content of Figure 7.1 does not concern us for now). The aim, when reading an MCA graph, then, is to begin the interpretive process by which social divisions can be understood. In simple terms, how is a given social universe structured? (See Figure 7.1)

Figure 7.1 A standard cloud of individuals and categories (Laurison, 2011)

A further advantage of MCA is the recovery of individuals. A common criticism of variable-based methods is that the individuals in the data are replaced by numbers (Abbott 1992). Again, the logic of regression analysis is quantitative (“Numbers are the basic ingredients and end products of procedures”, Le Roux and Rouanet 2004, 6). In MCA, the dots represent real individuals in the dataset. While not reducing the power of regression analysis, it provides further evidence of the potential of MCA and its elective affinity with meaning-centered approaches like Constructivism.

Through the use of computing power, MCA can handle larger amounts of data than the historically minded social scientist. Each datum of information provided in a dataset represents a dimension of difference among the individuals. The 2D images an MCA produces then are representations of n-dimensional space. Again, far more complex than the historically minded social scientist can handle.

Using MCA: an illustration from the field of political consultants

Figure 7.1 comes from a study conducted by political sociologist Daniel Laurison (2011) on the field of political consultants in the United States. Typically graphed separately, Laurison combines the clouds of individuals and categories. The small dots represent the actual individuals in Laurison’s dataset. The squares represent the average position in a social space of the individuals with characteristics covered by that category (job type, position, level of experience). The space is constructed using the measures of positions or capitals, not tastes or dispositions.

While the MCA plots a potentially large n-dimensional space, when it comes to interpreting an MCA the task is to analyze only those axes of difference identified that capture the most variance in the dataset. The amount of the total variance or ‘inertia’ is captured by the percentage figure next to each axis. Laurison retains two principal axes of division within this group of individuals for his analysis of what social divides structure political consulting in the US. The operative question, then, is what the axes mean.

As Laurison notes, the “first axis [the vertical axis, DM] describes an opposition between the dominant and the dominated or aspiring political consultants.” (2011, 260) Those at the top of Figure 7.1 are the dominant members of the field. They “earn the most money, work on the most races, and possess key field-specific capitals in the form of experience working for elected officials, having started out working on campaigns, and membership in the American Association of Political Consultants (AAPC)” (Laurison 2011, 260) The bottom of the graph is essentially the negative position: consultants located there earn less money, have participated in fewer races, and hold lower positions within consulting firms. This axis is thus a combination of economic and social capital in the world of US political consultants. The second, horizontal, axis “describes an opposition between the more politically-oriented consultants, on the right, and more commercially-oriented ones on the left” (Laurison 2011, 260).

Recall that the main aim of GDA is to explore the locations of individuals in social space – what traits they share, and crucially also what differentiates them. Here Laurison’s finding that there are broadly two groups: the experienced, wealthy, and primarily politically oriented, on the one hand, and the less experienced, lower earners and corporate-focused on the other, is interesting in and of itself. But the construction of the space also facilitates investigation of other aspects of the field, in particular the identification of what differences structure that social space (see Figure 7.2).

Figure 7.2 Structuring factors and the field of US political consultants (Laurison, 2011)

In Figure 7.2, Laurison highlights the average position of all the people who answered certain questions in a particular way: how old were you when you went into consulting? Do you have a Ph.D.? What is your age and gender? Inclusion of these so-called ‘structuring factors’ – which were not used in the MCA to construct the social space of political consultants – is both an aide to interpretation, and represents a move in MCA toward more familiar understandings of causal analysis, as the method uncovers statistically significant relationships between these attributes and the way the social space is structured.

From Laurison’s analysis, it is clear that there are relationships between the age at which an individual enters the social sphere of political consulting and where they end up, and that women and people of color are generally located in the dominated (i.e. less powerful segments) of the field. By further ‘projecting’ into the social space constructed by the MCA the responses of political consultants on questions of the ethics of consulting, Laurison also shows that the most powerful members of the field are most likely to view as acceptable some of the more morally circumspect polling techniques.

Some of Laurison’s other findings are less expected, however. Laurison shows for example that education does not ensure success in the world of political consulting. In fact, having a Ph.D. is a marker of dilettantism: real commitment to the cause means having been in the game since college – of course, easier for those of independent means and pre-existing political connections. This finding highlights the power of MCA: common sense might suggest that in a technical field like political consulting holding a high credential like a Ph.D. would translate into higher earnings, which turns out not to be the case.

Like standard statistics, MCA – and GDA generally – is advancing in sophistication and analytical power. It is an ever-moving target. To name one example, MCA can be profitably combined with cluster analysis (Aldenderfer and Blashfield 1984). This allows for the further analysis of sub-clouds produced by the MCA, which can address questions of the degree of separation between sub-clouds and the homogeneity or heterogeneity of parts of social spheres, again with the aim of aiding inductive interpretation.

Practical matters

The final task is to give a sense of the steps involved in using MCA and the challenges it poses. Best known outside of statistics as “Pierre Bourdieu’s method” – the French sociologist saw the affinities between MCA and his own theoretical perspective, deploying it in his Distinction (Bourdieu 1984; see Robson and Sanders 2009) – MCA brings with it a set of biases about the value of Bourdieu’s corpus, as well as the implication that MCA means adopting a Bourdieusian approach. Only a minimum theoretical commitment is required for using MCA, however: namely agreement with Bourdieu and other classical social analysts, notably Weber, who see society as separated into relatively autonomous social spheres in which the construction of reality occurs.

For Bourdieu and Weber, spheres like the cultural and economic are conceptualized as social fields and value spheres respectively. Other examples include sociologists Neil Fligstein and Doug McAdam’s own field theory (2012), or Andrew Abbott’s (2005) employment of the concept of social ecologies. In other words, using MCA implies only a willingness to move beyond the traditional state-centric approach in order to identify the social spheres that drive foreign policy behavior. These spheres might be limited to the government, as with the bureaucratic politics model of foreign-policy making (Allison and Zelikow 1999), but often an issue area extends beyond the state, into civil society and transnational relations.

MCA is thus useful if a deeper account of the social construction of policy is the aim, which brings into the foreground the institutions, organizations and individuals involved. (Note: If no struggle is taking place, MCA is not needed – the analyst can simply read off from the participants their rationales, interests or motivations, as fits with the analyst’s theoretical commitments. In most settings of interest to a social constructivist, however, social struggle will be taking place.) From the outset of the research design process, then, there is an assumption that certain social realms have separated themselves off sufficiently to be understood as something like a field. Beyond that, however, the scholar should make as few assumptions as possible about how a given space is constructed: its size, who is or is not a participant, the forms of power that decide who wins and who loses, the perspectives of any participants, and the relationship between the site of struggle and other institutionalized settings – such as the governmental bureaucracy. The aim of MCA is to answer these questions inductively.

An MCA could be run on institutional- and individual-level data. The collection of data follows a simple rule of thumb which separates information on the positions of the participants and their dispositions. The reason for this, in field theory terms, is that the structure of social space should be constructed either out of the forms of social capital participants hold, or information on the types of individuals that are involved and their dispositions or tastes. Constructing the social space out of both types of data would not only mix up different forms of information, it would also make it difficult to use the structure to uncover relationships between positions and dispositions. The orthodox approach is to let MCA construct the space from disposition variables by designating them ‘active variables’. This allows for the analysis of positions as supplementary variables.

Much work using MCA uses survey data from individuals. IR scholars have a traditional handicap in this regard, however, as interviewing elites is often difficult and costly, and few pre-existing datasets exist. One solution is to engage in what is termed ‘prosopographic research’, which focuses on the biographical characteristics of individuals. Prosopography can be done either by interviewing or by accessing varied sources such as memoirs, biographies, obituaries and résumés contained on personal and organizational websites. As much information – both positional and dispositional – is collected as possible, with the aim of enabling the MCA to uncover the latent relationships in the dataset.

Tactic and strategy: what does MCA get us?

The startup costs to using methods like MCA are considerable. There are few shortcuts to in-depth training, ongoing self-education, and significant time spent in trial and error. Since it is unlikely that any time soon doctoral methods training will automatically include methods like MCA, like they do regression analysis using Stata, interested students will have to attend one of a few specialized courses – which are far from free. Such practical issues are in addition to the standard problems of data collection.

Another set of obstacles will be persuading interlocutors from both sides of the methods divide. Constructivists can be the harshest critics of other constructivists’ work. They may misrecognize MCA and similar techniques as incompatible with Constructivism, perhaps deploying the problematic terms ‘quantitative’ and ‘positivist’, despite the arguments above. On the other side, the typical and often wrong-headed objections raised against constructivist work by non-constructivists – generalizability, unclear causation, etc. – will continue to be raised against work using MCA.

The reader persuaded to take on the task of engaging computational social science methods has their work cut out for them. Why then should students convinced of Constructivism’s value bother? MCA, I argue, represents a particular tactic for younger scholars who hope to work within the American academy as constructivists – whether they self-consciously adopt that label or not. To that extent, it should be supported by all constructivists – whatever their career stage – because it represents a viable strategy for continuing the constructivist research program in US IR by getting jobs for young constructivists.

The tactic of MCA responds to an important element of hiring decisions in US social science departments, namely the issue of whether an applicant has developed some methodological prowess through their graduate studies, as evidenced by having engaged in a significant new data collection exercise. Colloquially, this is the answer to the question, what did the applicant do? Reading books, newspapers, memoirs, and speeches, when faced with that question, look less impressive than developing a new dataset with the universe of cases of X, Y or Z.

Readers will bristle at this statement, and they are right to do so. Why is large-N or formalized rational choice work so respected when it may be a very problematic way of understanding international politics, as decades of constructivist and critical research has shown (see e.g. Kratochwil 2006). Why should constructivists have to be the ones to change?

The answer is that the norms and incentive structures of US political science cannot be ignored and for younger scholars have to be negotiated (see Subotic 2017). The alternative is to leave the academy, leave the US in search of work, or move on to lower prestige tracks. MCA, I suggest, is one way for high prestige-oriented younger scholars to try to have their critical/constructivist cake and eat the US political science department job too.

Adopting the tactic of MCA is not a concession to the quantitative side, however; it is not a cynical move. Using MCA means taking a wager that traditional constructivist methods of discursive analysis might – in fact – be missing some of the crucial unobservable social structures affecting international politics. A best case scenario of the use of MCA is that axes of social opposition common-sense would not suggest will be identified, meaning less intuitive accounts can be developed. In the worst case, MCA merely confirms divisions that might be expected from the outset.

Conclusion

If this chapter has been successful, it has done two things: first, if it has persuaded the reader that Constructivism is the IR heir to what C. Wright Mills terms classic social analysis, a core feature of which is to design methods that fit research problems, rather than vice versa. Constructivists are not only free but in some sense required to look far and wide for the most appropriate methods in their work from this perspective. Constructivists certainly should not adopt a method because it is what constructivists are ‘supposed’ to do.

Second, the chapter will have achieved its purpose if it has piqued some readers’ interest in the potential of new computational methods consistent with Constructivism’s core philosophical premises. The chapter has outlined Multiple Correspondence Analysis as one such method, but it will have been just as successful if the reader decides to investigate other methods like Network Analysis, Latent Class Analysis or Qualitative Data Analysis. Again, for many constructivists, it may not be deemed feasible or necessary to learn such methods. But it is appropriate on philosophical grounds and should not be prevented by the norms of disciplinary political science.

References

Abbott, Andrew (1992) “What Do Cases Do? Some Notes on Activity in Sociological Analysis” in What Is A Case? Exploring the Foundations of Social Inquiry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 53–82.

Abbott, Andrew (2001) Chaos of Disciplines. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Abbott, Andrew (2005) Linked Ecologies: States and Universities as Environments for Professions. Sociological Theory 23 (3): 246–274.

Aldenderfer, Mark S. and Roger K. Blashfield (1984) Cluster Analysis. London: Sage.

Allison, Graham and Philip Zelikow (1999) The Essence of Decision: Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis, 2nd edition. New York, N.Y.: Pearson.

Barkin, J. Samuel and Laura Sjoberg (eds.) Forthcoming. Interpretive Quantification: Methodological Explorations for Critical and Constructivist IR. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Becker, Howard (1953) Becoming a Marihuana User. American Journal of Sociology 59 (3): 235–242.

Bourdieu, Pierre (1984) Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Bühlmann, Felix, André Mach and Thomas David (2012) The Swiss Business Elite (1980–2000): How the Changing Composition of the Elite Explains the Decline of the Swiss Company Network. Economy and Society 41 (2): 199–216.

Denord, François, Johs Hjellbrekke, Olav Korsnes, Frédéric Lebaron and Brigitte Le Roux (2011) Social Capital in the Field of Power: The Case of Norway. The Sociological Review 59 (1): 86–108.

Flemmen, Magne (2012) The Structure of the Upper Class: A Social Space Approach. Sociology 46 (6): 1039–1058.

Fligstein, Neil and Doug McAdam (2012) A Theory of Fields. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Grenfell, Michael and Frédéric Lebaron (eds.) (2014) Bourdieu and Data Analysis: Methodological Principles and Practice. Bern: Peter Lang.

Hayes, Jarrod (2017) Reclaiming Constructivism: Identity and the Practice of the Study of International Relations. PS: Political Science and Politics 50 (1): 89–92.

Jackson, Patrick Thaddeus (2011) The Conduct of Inquiry in International Relations: Philosophy of Science and Its Implications for the Study of World Politics. London: Routledge.

Kratochwil, Friedrich V. (2006) History, Action, and Identity: Revisiting the ‘Second’ Great Debate and Assessing Its Importance for Social Theory. European Journal of International Relations 12 (1): 5–29.

Laurison, Daniel (2011) “Positions and Position-Takings Among Political Producers: The Field of American Political Consultants” in Michael Grenfell and Frédéric Lebaron (eds.) Bourdieu and Data Analysis: Methodological Principles and Practice. Bern: Peter Lang.

Lebaron, Frédéric (2001) Economists and the Economic Order: The Field of Economists and the Field of Power in France. European Societies 3 (1): 91–110.

Le Roux, Brigitte, and Henry Rouanet (2004) Geometric Data Analysis: From Correspondence Analysis to Structured Data Analysis. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

McCourt, David M. (2011) Rethinking Britain’s Role in the World for a New Decade: The Limits of Discursive Therapy and the Promise of Field Theory. British Journal of Politics and International Relations 13 (2): 145–164.

McCourt, David M. (2014) Britain and World Power: Constructing a Nation’s Role in International Politics. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press.

McCourt, David M. (2016a) Practice Theory and Relationalism as the New Constructivism. International Studies Quarterly 60 (3): 475–485.

McCourt, David M. (2016b) Constructivism’s Contemporary Crisis and the Challenge of Reflexivity. European Review of International Studies 3 (3): 40–51.

Mills, C. Wright (2000 [1959]) The Sociological Imagination. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nexon, Daniel (2009) The Struggle for Power in Early Modern Europe: Religious Conflict, Dynastic Empires, and International Change. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Onuf, Nicholas (1989) World of Our Making: Rules and Rule in Social Theory and International Relations. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press.

Pouliot, Vincent (2011) International Security in Practice: The Politics of NATO-Russia Diplomacy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pouliot, Vincent (2016) International Pecking Orders: The Politics and Practice of Multilateral Diplomacy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Prieur, Annick, Lennert Rosenlund and Jakob Skjott-Larsen (2008) Cultural Capital Today: A Study from Denmark. Poetics 36: 45–71.

Robson, Karen, and Chris Sanders (2009) Quantifying Theory: Pierre Bourdieu. Dordrecht: Springer.

Rosenberg, Justin (1994) The International Imagination: IR Theory and ‘Classic Social Analysis’. Millennium: Journal of International Studies 23 (1): 85–108.

Rosenberg, Justin (2016) IR in the Prison of Political Science. International Relations 30 (2): 127–153.

Ruggie, John Gerard (1998) What Makes the World Hang Together? Neo-Utilitarianism and the Social Constructivist Challenge? International Organization 52 (4): 855–885.

Steele, Brent J. (2017) Introduction: The Politics of Constructivist International Relations in the US Academy. PS: Political Science and Politics 50 (1): 71–73.

Subotic, Jelena (2017) Constructivism as Professional Practice in the US Academy. PS: Political Science and Politics 50 (1): 75–78.

van Meter, Karl M., Marie-Ange Schlitz, Philipp Cibois and Lise Mounier (1994) “Correspondence Analysis: A History and French Sociological Perspective” in Michael J. Greenacre and Jörg Blasius (eds.) Correspondence Analysis in the Social Sciences: Recent Developments and Applications, 128–138. San Diego, Calif.: Academic Press.

Wendt, Alexander (1992) Anarchy is What States Make of It: The Social Construction of Power Politics. International Organization 46 (2): 391–425.