FRAU PERCHTA, WITCHES, AND GHOSTS

Witch and Goddess, Benevolent Monster

Opening this book, you knew you would read about the devils, but now we’ll see how witches too figure into our dark holiday.

The witch in question—though she’s also called a goddess—is a figure known primarily in Austria and Bavaria as Frau Perchta. Her name, as you might have guessed, associates her with the Perchten, Alpine spirits already mentioned as prototype for the Krampus. She goes by Pehrta, Berchte, Berta, and a myriad of other related or regional names. In Germany, north of Bavaria, her counterpart is Holda (also Holle, Hulda), identified from the 11th century onward by concerned churchmen like Burchard of Worms as the leader of an infernal horde. Martin Luther seemed to know her as a grotesque mumming figure, referencing in one of his sermons a weird “fraw Hulda,” characterized by a long snout, rags and “straw armor.” To this day, Alpine folklore paints Perchta as a monstrous being, eating, tearing asunder, or disemboweling those who displease her.

She is also a beautiful otherworldly matron whose name evokes purity and light.

Like the Perchten, Perchta is a creature of dualities, and makes her rounds on appointed winter nights to both reward and punish according to deed. The customs associated with her are largely those reimagined by the Church in the traditions of the Krampus and Nicholas. She is, in this sense, the egg from which it all hatches.

Before discussing witches, I should briefly explain these Perchten you’ve been hearing about. This class of spirits is divided into two species, the good or “beautiful” Schönperchten, and the bad or “ugly” Shiachpercht, the latter being the model, naturally, for the Krampus. Just as the Krampus has experienced a modern revival, the Perchten too are very much alive in contemporary Austria and southern Germany. There are probably hundreds of Perchten groups and dozens of dedicated Perchten runs. With increasing frequency, Perchten swell the ranks of events promoted as Krampus-runs.

The modern Perchten group or Perchten run is almost exclusively the domain of the Schiachperchten. The beneficent Schönpercht usually today only receives attention as a historical footnote, so when I speak of Perchten without identifying them as either “schön” or “schiach” readers may assume the latter. This duplicates typical usage in German literature and media. While there is a handful of towns with more traditionalist events at which costumed Schönperchten do appear, most of these only date to the 1930s or ’40s. One exception to this is Gastein, where a continuous Perchten tradition can be traced to the early 1800s.

Visually, however, the modern Percht is mostly indistinguishable from the Krampus, wearing the same furs, horned mask, and bells. He caries an instrument with which to strike passersby, sometimes switches but more commonly the horse-tail whip. As a pagan figure, the blows he administers are not regarded as punishments for un-Christian behavior, but more loosely interpreted as “bringing luck,” “driving out evil,” and the like. While it’s questionable, many sources insist horse-tail whips are the preferred instrument of the Percht. Even more often, the number of horns on the mask will be cited as a defining feature, with two signifying Krampus and four or more indicating Percht.

This matter with the horns is a preoccupation of instant experts, a beloved factoid in popular media introductions to the Perchten, and within the participant community, the stick with which to beat rivals supposedly ignorant of or betraying the tradition. However, for an anthropologist like Rest, who has grown up in traditionalist Gastein, “it is a totally a nonsensical discussion—who is Percht and who is Krampus.” As detailed, Gastein’s history with the Krampus is one of fluid and organic evolution, and even the Perchten and Krampus were actually undifferentiated.

“Here, the mask does not make a difference,” Rest says. “Those masks used for the Perchten parades are the same used for the Krampus. Only people who are not schooled in the old tradition have this idea of a material difference between the two things. But to us it’s totally contextual.”

The context to which Rest refers is specifically calendric. While the Krampus is strictly associated with St. Nicholas Day, the Perchten are most strongly associated with Epiphany, on January 6. In fact, Perchta’s name, in its many variations, is usually understood as a corruption of the Old High German term for Epiphany, “giberahta naht,” meaning, the “night of shining forth or manifestation.” Here the reference is to Christ’s manifestation to the world as represented in his “discovery” by the Magi or the disclosure of His divine nature during baptism in the Jordan. It is also possible the word “Giberahta” alone may be the source, making Perchta something like “the Shining One.” Lovely as this sounds, it is unfortunately speculative, as none of the early texts otherwise identify Perchta specifically as “shining” but do specifically portray her as tied to the days around Epiphany.

Perchta and Holda are also sometimes associated with the Ember Days. Like the seasonal Quarter Days celebrated by modern Neopagans, the Ember Days are four sets of fast-days marked by the Church. Of these, Perchta is almost exclusively associated with the Winter Ember Days falling on the Wednesday, Friday, and Saturday after the December 13 Feast of Saint Lucy. In the Austrian state of Carinthia and in adjacent Slovenia, once part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Perchta was sometimes called Quatemberca (a Germanicized contraction of quattuor temporum, “quarter time”). She was also called Frau Faste (Lady of the Fast).

Because of Perchta’s strong textual connection to Church holidays, some have therefore suggested that the figure—at least originally—was simply a personification of a Christian feast, similar to Father Christmas embodying that holiday, making her the equivalent of “Lady Epiphany.” Some go even further, speculating that she may simply be an aspect of the Blessed Virgin as “Our Lady of Epiphany.” But practices associated with Perchta have a long history of attracting the outrage of Catholic clerics. Even if corrupted in practice by peasant superstition, it seems unlikely that the figure central to these practices would have provoked such harsh criticism.

The calendric personification theory did not satisfy Jacob Grimm, and in his impressively exhaustive Deutsche Mythologie, he rejects the notion, pointing to Perchta’s virtual identity to the more clearly pagan figure Holda. Perchta, for Grimm, therefore would simply be regarded as a localized name for Holda. While not identical on all points, the confluence between these two mythical figures is strong enough that modern scholars often treat the two beings as a single entity, hyphenating “Holda-Perchta” for ease of discussion.

In brief, those common traits describe a supernatural being primarily associated with the end of the year (Perchta exclusively so). Both are particularly involved with females and children, with spinning, weaving, and domestic order. Both are also known for nocturnal travels with hosts of unquiet spirits the Church regarded as damned souls or demons. Both figures can bestow blessings or invoke terror, with Perchta being more known for a frightening aspect and punitive acts. As further evidence of Holda and Perchta’s identity, Grimm points to similar, lesser known, folkloric figures in whom the names combine, such as Berchthold and Hildaberta.

Perchta and Holda are often assumed to be ancient goddesses worshiped by early Germanic or Celtic tribes, but it should be kept in mind that Romanization of Celtic settlements in the Alps had already begun at the dawning of the Common Era, with Christian missionaries arriving and beginning conversion of the area by the 2nd century. Germanic tribes entering the areas had already converted by the 5th century. With the first mention of Holda-Perchta in the written record not occurring till around the year 1200, we’re left with approximately seven centuries of Christianizing influence and intermingling of beliefs, making any precise equations with older, more pristine forms of Celtic or Germanic paganism questionable. Grimm’s efforts to connect the medieval Holda (and consequently Perchta) to the ancient Germanic goddess Frigg/Freya are today viewed with skepticism.

Even the term “goddess” Grimm and countless others have used to describe the figures might be questioned. Particularly in the case of Perchta, it seems a little misleading. Depending on context, both Perchta and Holda might just as well be regarded as beings from the fairy realm, guardian spirits associated with a particular place (a mountain or spring) or with protected persons (children, women). In malevolent guise, they may be no more than bugaboos invoked by parents to frighten misbehaving children. This is especially the case with Perchta. These figures were indeed objects of cult veneration and ritual practices ultimately persecuted by the Church as witchcraft, but identifying cults like this only first described in the Early Modern Era with a paganism in its pre-Christian heyday remains a dubious affair.

This notion of Holda as a goddess of primordial provenance has its counterpart in romantic mythologies created by those involved with contemporary Perchten events. The webpage of the Steyrtaler Perchten from Steinbach, Austria, for instance, implausibly describes the Perchtenlauf as a “monument to a long-vanished nature religion, whose roots date back to the Stone Age.” Perchta or Holda also show up in New Age circles as names for an impossibly old and multicultural “Divine Mother.” As such, they are also celebrated in the relatively recent phenomenon of “Alpine Shamanism” in which drumming and crystal workshops (even Reiki) are jumbled up with hikes to various mountain destinations inevitably revered by local Celtic or Germanic tribes as “sacred sites.” To compensate for the grandiosity of claims like this, I avoid the term “goddess” in discussing these figures when possible.

The first mention of Perchta appears around 1200, but the word “Perchten” is not employed until centuries later. In 1468, there appears a reference to her retinue, but its members are not called Perchten, nor do they explicitly resemble Perchten as we think of them today. At this stage in Perchta’s mythology, the company she leads is most often understood as spirits of the departed. With time, and frequent attacks from the pulpit, Perchta’s pagan company came to be commonly feared not as ghosts but as demons, something presumably closer to the horned figures we now know. It’s here, via Frau Perchta’s horde, that we find a connection between the Krampus and the souls of the dead. This is the connection hinted etymologically by the Bavarian “Krampn” (“lifeless” or “shriveled”) some believe to be the source of the devil’s name.

In the same era we see the myth of Perchta’s eerie night-traveling horde spreading, we also begin hearing of masqueraders impersonating this frightful host. Here the proper name “Perchta” seems to transform into the collective species, “Perchten.” We have already seen how the name of a singular individual like “St. Nicholas” could unexpectedly pluralize in reports of rough “Nicholases” troubling towns. Likely the process with Perchta was analogous. Quite possibly, the early masker in a Perchten processions saw himself not as representing a demonic male follower of Perchta, but as Perchta herself, or more accurately, as one of a multiplicity of female Perchtas. The tradition of men costuming as female characters was, after all, part of folk-theater and Carnival traditions.

The very first illustration we have of Perchta seems to show not the figure herself, but in fact a masker. In South Tyrolean poet Hans Vintler’s 1411 Die Pluemen der Tugent (“The Flowers of Virtue”), various superstitions are derided, including a belief in women like “Percht with the iron nose.” Perchta’s long or beaklike nose is a characteristic feature, and is often described as being of iron (as are, sometimes, her hands, teeth, and warts.) The illustration shows a figure with a face not only grotesque but seemingly artificial, with eyes peering out of what appear to be holes in a mask, and hands notably bulky and claw-like, as if gloved. Also occurring very early is the previously mentioned image of a Holda-Perchta costume from a 1522 sermon by Martin Luther, that of “fraw Hulda” wearing “straw armor,” something we can imagine, perhaps, as being similar to the Schabmann of the Bad Mitterndorf Nicholas play.

Frau Perchta (right) from Hans Vintler’s Die Pluemen der Tugent (“The Flowers of Virtue”) (1411). Redrawn from manuscript by Lauren Church.

In the 17th century, we have the first reports of Perchten runs from the Pongau (the area around Gastein), and by the 18th similar accounts are appearing elsewhere. Perchten events in these days would begin around St. Nicholas Day and peak around Epiphany. This range of dates once more reminds us how the Krampus and Perchten traditions were earlier undifferentiated. The dates also tend to reinforce Grimm’s notion that Holda-Perchta’s connection with Epiphany is not intrinsic to the tradition, rather a matter of later ecclesiastical syncretization.

A creature we would today recognize as a Percht (or Krampus for that matter) has took shape by the 18th century. From the Tyrolean town of Kitzbühel, we have a 1736 report complaining of a late night disturbance by “most repulsive spirits, in devil masks” running about the town with noisy bells.” By the early 19th century, documentation of Perchten events is not uncommon. Many of these clearly demonstrate an overlap with Nicholas-Krampus customs as well as deviation from the fixed date of Epiphany. In 1857, a J.V. von Zingerle reports on a Tyrolean Perchtenlauf held not on January 5 but weeks later on the last day of Carnival, and mentions not only frightening maskers, but also Perchten figures who distribute gifts in the manner of Nicholas.

The 1848 book Bavarian Legends and Customs describes the custom of youths impersonating “Iron Bertha” (Bertha being another derivation of Berchta or Perchta). Disguised in cowhides and horns, she goes about frightening some children and rewarding others with apples, pears, and nuts. In the same volume, we hear from Oberhausen, Germany, where a Nicholas (“Kläs”) and a Percht were paired. The Percht here appears with wild hair, soot-blackened face, and black rags. She is known as “Buzabercht,” combining the name Bercht (or Berchta) with “Buz” (“bugaboo”), as we’ve seen in the 1750 woodcut, Die Butzen-Bercht, featuring the crone and her basket of children. While Nicholas performed his usual duties, the Buzabercht attacked the ill-behaved, not only with switches but also by smearing them with starch from a pot she carried for the purpose. In another account from Göttingen, Perchta arrives on New Year’s Eve rewarding good children with undershirts, of all things.

Domestic Oversight and Female Perchten

Perchta’s visits were primarily oriented toward ensuring compliance in certain household duties. Of particular interest was the spinning of flax, which was to be completed by Epiphany Eve. Should she find any unspun flax still on the distaff or about the house, it would be cut, tangled, or otherwise ruined by Perchta. Grimm mentions her burning the hands of lazy spinners. Austrian mythologist Lotte Motz goes further, stating that Perchta was said to wipe unspun flax with her excrement.

She was also interested generally in tidy housekeeping, and homes were to be thoroughly swept and scrubbed by the time she made her rounds. According to some scholars, this broader attention to tasks beyond spinning was a later development, appearing once the centrality of spinning as a cottage industry waned. Menial housekeeping in those days would naturally fall to young girls and unmarried women working as servants, making Perchta a creature of the female sphere.

While this may seem a long way away from the male dominated world of the modern Perchtenlauf, certain masked Perchten activities do directly reference Frau Perchta’s role as enforcer of household order. In the small town of Rauris, about 30 miles west of Gastein, you’ll find birdlike Schnabelperchten (“beaked Perchten”), who visit homes to inspect room for tidiness, while quietly and mischievously causing “accidental” messes in the process. Although played by males, performers cross-dress as old women, preferring grandmotherly kerchiefs, patched skirts, sweaters, and archaic straw slippers sometimes called “witches’ slippers.” Unlike the raucous bell-ringing Perchten, they move about with eerie stealth, slipping into homes in groups of four or five, softly clucking “Ga, Ga, Ga,” in droning chorus. Their elongated beaks, probably inspired by Perchta’s prominent nose mentioned by Vintler and others, are made of old linen and sticks, and are intricately rigged to clap with each chirped syllable. The Schnabelperchten bring brooms with which to sweep and large wooden scissors hinting at Perchta’s tendency to cut open bellies. On their backs, they wear wicker baskets, sometimes fixed with large protruding doll legs, lest children forget that Schnabelperchten, like the Krampus, may abduct any who fail their obligations. Schnabelperchten of this sort are also found in the large, traditionalist Perchtenlauf held in Altenmarkt, Austria.

The Belly Slitter and Her Dreadful Ways

Rhymed text accompanying the previously mentioned woodcut depicting the “Butzen-Bercht,” with her dripping, warty nose and basket of screaming children, clearly demonstrates that by 1750, when the depiction was created, Perchta’s appetite for punishing wayward children was neatly suited to evolve into the figure of Krampus.

Here is my unrhymed translation of a portion of the Butzen-Bercht boast:

… So you shall not escape

My old broomstick, the whips, and the rod

With which I’ll beat you till you’re red with blood.

You hands and feet I’ll bind

And throw you into the mire,

Set fire to your braids and hair,

Scratch your face, and cut your nose,

And rough you up quite well.

All your dolls I’ll toss and burn,

And shred your finest Sunday dress.

The distaff I will fill so full of snot

That it drips and runs.

When I find you snoring late in bed,

I’ll reel your intestines out from your belly

And fill the hole with wood shavings and tow …

(“tow” = waste fibers combed from flax before spinning)

Perchta was particularly notorious for slitting open and gutting her victims. She might carry a sickle, knife, or scissors for this frequently required job. Sometimes, she would even perform this operation in order to remove foods consumed on her holy day not matching her dietary prescriptions. Straw, snow, dirt, pebbles, and assorted garbage as well as the above mentioned tow and shavings were then used to fill the cavity. She then finished up this bit of makeshift taxidermy by sewing the victim shut with a needle made of iron. Or in more hyperbolic stories, a ploughshare.

Frau Perchta with butcher assistant. Drawing by Karel Rozum for Den se krátí, noc se dlouží (“The Day is Short, the Night Lengthens”) (1910).

Another punishment associated with Perchta was her tendency to stamp on those who offend her. In certain regions, it is the Stempe, or the Trempe (from the German words for “stamp” or “trample”) who appears to frighten the disobedient on Twelfth Night.

In a medieval poem, quoted in Grimm’s Deutsche Mythologie, a child is threatened with the Stempe should he fail to eat the dinner served him. The manuscript from which Grimm worked featured an addendum re-titling the poem “Of Perchta with the Long Nose” confirming the identity of the two characters. Although undated, the poem was composed in Middle High German, spoken from approximately 1050 to 1350, making this one of our earliest references to a Perchta-like figure.

The unrhymed verse here is a translation from the English version of Deutsche Mythologie.

Now mark aright what I you tell:

After Christmas the twelfth day,

After the holy New-year’s day

(God grant we prosper in it),

When they had to table brought

All that they should eat,

Whatso the master would give,

Then spake he to his men

And to his own child:

‘Eat fast (hard) to night, I pray,

That the Stempe tread you not.’

The child then ate from fear,

He said: ‘Father, what is this

That thou the Stempe callest?

Tell me, if thou it knowest.’

The father said: ‘this tell I thee,

Thou mayest well believe me,

There is a thing so gruesome done,

That I cannot tell it thee:

For whoso forgets this,

So that he eats not

On him it comes, and treads him.

Perchta’s vengeful foot has also led to her being described as having large feet, or more often, a single large foot, i.e., Berhte mit dem fuoze (“Perchta with the foot”) or Berhta cum magno pede (“with the big foot“). Grimm suggests this may recall Perchta’s relationship to spinning and the heavy foot of a spinner constantly upon the treadle. He also explains the mismatched foot as an archetypal signifier of a supernatural being, as with the Devil’s cloven hooves, or hoof. This physical marker seems to have been transferred to the Krampus as well, and is particularly prevalent in Krampuskarten showing the creature with one human foot and one hoof. Grimm also points to a conflation with the 8th century Frankish queen Bertrada of Laon, the mother of Charlemagne, known as Bertha Broadfoot thanks to Adenes Le Roi’s 13th-century poem Berte aus grands pies. Le Roi does not make clear the significance of the large foot, which he also refers to as a “goose foot.” From this evolved a French fairy figure Queen Pèdauca (from pied d’oie or “goosefoot”), who like Perchta is associated with spinning. Pèdauca is often presented as telling stories while she spins, thereby also relating her to the English Mother Goose.

As mentioned, Frau Perchta can be quite particular about food. On the nights she appeared, there were specific foods to be eaten by those she visited as well as foods to be left as offerings to her. Omissions again resulted in gutting, but compliance at least ensured blessings in the coming year. From place to place, her requirements varied, but included fried dumpling dishes (Semmede), herring, eggs, and especially a milk porridge called Perchtenmilch, alternatively Sampermilch (boiled milk with bread slices) or Bachlkoch, a porridge drizzled with honey.

Families would be expected to eat their fill of these designated foods and reserve some uneaten for Perchta and company. Saved portions of this ritual meal would either be left on a specially prepared Perchtentisch (Perchten table) or fed to the farm animals to bless them with good health and fertility. For the convenience of her retinue, the offering might be left outside under a tree, or in the branches, or on a rooftop where night-flying spirits might most easily receive it.

Costumed Perchten visiting homes would also expect food in exchange for “bringing good luck.” Their requests could mix threats and begging, as did trick-or-treaters in Halloween’s wilder past. Perchta was, like the Krampus, sometimes said to abduct and/or eat children, and one rhyme used to shake down householders playfully threatened:

Kinder oder Speck,

Derweil gehe ich nicht weg.

(“Children or bacon,

Or I won’t go away!)

Feeding Perchta greasy foods could also save you from her iron grip, as it was said she must remove her iron gloves in order to eat such things. Alternatively, eating fried dumplings could save you from her knife, as greasy foods made the belly “too slippery” for her to slash. Milk porridge left overnight for Perchta and her entourage, even if apparently untouched, was said to be drained and mysteriously restored. How the bowl was found the next day could also serve as oracle for the coming year, as in this account from Hofstetten-Grünau, Austria, published in 1900:

One should leave half of {the milk porridge} and leave the spoon stuck in it or lying on the edge of the bowl so that both ends hang free. Then around midnight, Perchta, with her host of children who have died unbaptized, will come to eat the porridge, and if you hear their slurping, you know the house is blessed for the entire year. The following morning … if the spoon you left is moved, you have misfortunes to fear in the coming year. If your spoon has fallen into the bowl, the next year will bring your death. If your spoon has fallen out, you will depart from your house. Unmarried people whose spoon has much milk skim on it, will soon be married.

Those invisible infants slurping Perchtenmilch in the night are called the Heimchen. This word also can translate as “cricket” and is used to describe a shy or retiring individual, especially a young female. Whether the evocation of diminutive, nocturnal, or evasive beings is etymologically related or intended is uncertain. The relationship of the unbaptized babies to the old lady Perchta Grimm describes rather neatly: “As the Christian god has not made them His, they fall to the old heathen one.”

The Heimchen figure into many stories told about Frau Perchta, some identical to those told of Holda, also given charge over the unbaptized dead. In one of the best known, a peasant out late one Epiphany Eve encounters Perchta’s entourage and notices a particularly small child repeatedly tripping on the tails of an overlarge shirt. The kind peasant cries out, “Oh, you poor ragamuffin!” and binds up the troublesome shirt. The Heimchen thanks the peasant for addressing him by name. In calling the child “ragamuffin,” the stranger has christened the child with a sort of name, a de facto baptism that frees his soul from nocturnal wandering.

A final example has Perchta and the Heimchen blessing the farmers of a certain region with nocturnal attention to their crops. The story begins with Perchta wishing to leave the locality, arriving with her host of ghost children at the edge of a river, where she bids a ferryman take them across. The ferryman hesitates, seeing the massive throng she intends to board as well as the plough she wishes to transport. Nonetheless, he agrees to carry Perchta, her plough, and a portion of the children. As they drift over the water, Perchta tends to the plough, which needs mending, chipping away at the instrument, and leaving a pile of debris. When the ferryman hesitates to make additional trips for the rest of the Heimchen, Perchta offers a reward—the wood chips that lay around the mended plow. Angered by the gesture, the ferryman nonetheless returns to transport the rest of the Heimchen, grabbing three of the chips in disgust. After finishing his work, he returns home from the river. On waking the next morning, he finds the chips magically transformed into three gold coins.

Other folklore of the Heimchen has them visibly manifested as will-o’-the-wisps, the ghost lights, or ignis fatuus appearing particularly over swamps and said to lure from known footpaths unwary travelers mistaking them for village lights or helpful beings.

Usually consisting of unbaptized innocents, the company of Perchta (and perhaps even more Holda) may include others somehow misplaced by fate, in particular, those who have died before their time. Destined to wander until their appointed hour, these wards of Perchta, who failed to attain their allotted days, were later joined by others the Church found somehow worthy of neither heaven nor hell. These lost souls included suicides, those slain by arms, and later, witches and wizards. The ghostly followers of Perchta over time thereby came to be regarded as no longer merely eerie, but increasingly malevolent.

As mentioned, Holda’s (or Holle’s) domain is mostly identical to Perchta’s. She is particularly associated with the twelve days between Christmas and Epiphany. During that period, she is said to travel about, sometimes riding a wagon or on horseback. While she’s also given charge over spirits of the unbaptized or those not ready to enter heaven, her entourage may at times also resemble a ghostly hunting party, and as such merges with the mythologem of the Wild Hunt, a theme explored in greater detail later. Like the classical Goddess Diana, with whom Latin-trained clerics often compared her, Holda might appear as a huntress, blowing a hunting horn, or be followed by a train of dogs. Perchta too, as in Tyrol’s Eisack Valley and elsewhere, was sometimes accompanied by the souls of children taking the shape of dogs.

Holda-Holle also oversees spinning and domestic order, and rewards and punishes those who fulfill these responsibilities. In Hesse, where her tradition remained strong, children until recently would set out bowls on New Year’s Eve, which would be filled by morning with sweets if merited. For the poorly behaved, she would leave switches.

Domestic duties figure prominently in the best-known tale associated with Holda, one published in 1812 in Grimm’s Children’s and Household Tales. Rendered in English as “Mother Hulda,” in German it’s known as “Frau Holle,” using the more common name for the figure in Grimm’s native Hesse, where the story was collected.

In the tale, the stepdaughter of a rich widow is treated cruelly by her stepmother and lazy stepsister. One day while spinning by the family well, the stepdaughter pricks her finger on her spindle. As she washes the blood at the well’s edge, she accidentally drops the spindle into its depths. Fearing her stepmother’s wrath, she leaps in to retrieve the item, falling into darkness and awakening in a magical landscape. There she encounters an apple tree begging her to pluck the heavy fruit from its limbs and baking bread asking to be removed from the oven. After successfully performing these tasks, she meets old Mother Hulda, whom she dutifully helps with household chores. One of these is to help Hulda shake out her feather bed, which scatters down that falls as feathery snowflakes into the mortal world. As the stepdaughter grows homesick, Mother Hulda sends her back to her world, but not before rewarding her with a shower of gold, that transforms her into the glittering “Gold-Marie.” Her envious stepsister plunges into the well in hopes of obtaining the same, but is too lazy to complete her tasks, and returns from Hulda’s magic realm showered with pitch and known as “Pitch Marie.”

Along with her association with spinning, the story reflects the figure’s connection to winter, incorporating an old superstition about Holle bringing snow. Additional stories depict Holle doling out rewards and punishments according to behavior. Incognito as an elderly “Aunt Mählen” she begs for food and shelter, magically rewarding those who show generosity. Asking such charity of a bee keeper, Holle/Mählen is fed by his daughter, provoking an angry blow from the girl’s stingy father. In retribution, Holle sets the apiary and estate ablaze, killing the father, but miraculously preserving the daughter even within the flames.

Frau Holle and the Heimchen, from Das festliche jahr: in sitten, gebräuchen und festen der germanischen Völker by O. Spamer (1863).

Just as Perchta’s association with agriculture is represented by her plough in the tale of the ferryman, even more stories emphasize Holda’s connection to nature and the fertility of crops, animals, and humans. Her passage over a farmer’s land was said to ensure a bountiful harvest. She is also strongly associated with the life-giving waters of springs, ponds, and streams, and is sometimes spotted in the noonday sun near bodies of water, dressed in shining white and only visible for an instant before vanishing.

Particularly powerful is her connection to the Frau Holle Pond on the Hohen Meißner mountain complex in Hesse. Since at least 1641, the landmark has been identified with her name, but the association may have begun much earlier, possibly even as a site of sacrifices as suggested by the discovery of medieval potsherds and 1st-century Roman coins in its depths. Legend describes the pond as deep beyond measure, and somewhere within is Holda’s silver palace amid a luxuriant world of fruit and flowers.

The waters have long been sought out by female bathers seeking health and fertility. Up into the 1930s, women gazing into the pond were said to be able to discern their unborn children sleeping below, and would see the tips of the hairs on these children’s heads in the reeds protruding from the surface.

Since 2004, a sculpture of Holle has stood on the banks of the pond, which has been incorporated into a 115-mile Frau Holle Path, a route connecting various sites associated with the figure and marked by informational displays. Among the local sites where Holle’s blessings are sought and flowers may be left are a rock formation on the south side of the Meißner, known as the “Frau Holle Chair,” two dolomite crags (known as the Holle Stones). The subterranean waters of the Holle Cave and the Witches’ Pond, are said to be particularly salubrious, particularly for bathers who visit on Christmas or May Eve. Nearby, the town of Hessisch Lichtenau bills itself as “The Gateway to Holle-Land.” In 2011 the municipality reopened its old cross-timbered courthouse as the Frau Holle Museum or “Holleum.”

While the ugly, large-toothed character Grimm describes as “Mother Hulda” is now mostly remembered as a charming grandmotherly type, the Holda of folk tales and legends also possessed a darker side more reminiscent of Perchta. Like Perchta, who is said to reside in certain Tyrolean caves with the spirits of the unbaptized and unborn, Holda sometimes eerily merges cradle and grave and makes clear her identity as matron of both death and regeneration.

A geographical focus of this darker aspect is the Hörselberg, a mountain near Eisenach, Germany, where Holda and her host are said to reside in underground caverns. The mountain has a long history associating it with the otherworldly. Legend credits medieval monks for naming the mountain “Hear-Souls Mountain” (“Hör-Seel Berg”) after perceiving the wailing of lost souls from within. Local tradition, for centuries, has described Holda emerging from the mountain with her horde either on Christmas Eve, New Year’s Eve, or the Winter Ember Days. Though not as common, a similar legend attached itself to Kyffhäuser, a mountain in Central Germany where a 12th-century Holy Roman Emperor Friedrich Barbarossa and his armies are said to repose, waiting to be called forth in Germany’s hour of greatest need.

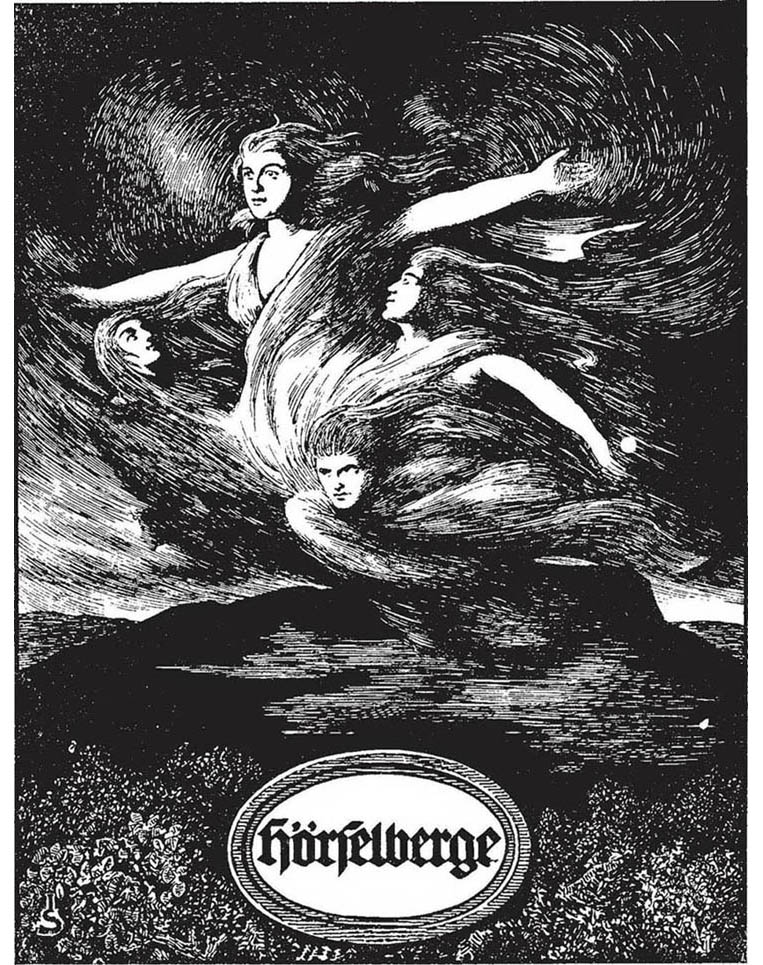

“Frau Hulla and the Wild Host” by Joseph Sattler for Hörselberg Monthly, vol. 1. (1927).

First mentioned in the late 1400s, the notion of the Hörselberg as home to Holda and her phantoms may have been influenced by earlier Italian tales of a witch queen, Siballa. Named after the oracular Sibyl of Cumae, Siballa was said to reside under the mountains near the Umbrian town of Norcia, an area for centuries associated with witchcraft. Roughly a century before Holda’s residence in the Hörselberg is mentioned, tales of the Italian Siballa’s subterranean existence around Norcia began to circulate. In 1442 French courtier Antoine de la Sale visited the areas, claiming to discover the entrance to the witches’ caverns. Finding inscribed on the portal names of knights and sorcerers who had entered but never returned, La Sale turned away, content with his discovery and the local legends he had collected telling of bacchanalian orgies enjoyed within the mountain.

By the early 1400s, German balladeers were telling a similar tale of Tannhauser, a 13th-century Minnesinger, recast as poet and knight who enters the Venusberg, a magical realm where he devotes himself to Venus, endless revels, and erotic adventures. Goaded by Christian conscience, Tannhauser attempts to revisit the mortal world, but is condemned to return to the Venusberg. Tannhauser’s tale, with characteristic reworking and the addition of an umlaut, was recast as Wagner’s 1845 opera Tannhäuser, one notorious in its day for its lurid opening scene depicting the erotic indulgences of Venus’ court.

In 1501, Wolfgang Heider, a professor at the University of Jena, placed the Venusberg in the forests of Thuringia, where both the Hörselberg and Kyffhäuser are found. He also marked Christmas as the time at which the supernatural horde emerges, describing ghostly troops of men on horse and on foot, as well as “lemurs, larvae, and empusae,” the first two being malignant ghosts that haunted the Romans, and the latter monstrous servants of the goddess Hecate.

Heider’s use of classical terms to describe the superstitions of German peasants is typical of clerics trained in Latin. The writings of the 15th-century Bavarian Dominican Johannes Herholt are illustrative here. In this Sermones, Herholt expands upon Burchard’s comments about a “Diana” called “Holda” by the peasants. To Burchard’s equation of Diana with Holda, Herholt adds “Fraw Berthe” (Frau Perchta) as yet another equivalent name. He also changes Burchard’s “Holda,” to “Unholde.” We already understand the identity of Holda with Perchta, but where does this “Unholde” come from?

In modern German, “unhold(e)” means unholy or monstrous, while the word “hold(e),” if not the exact opposite, means graceful, charming, or dear. In providing an etymology for Holda’s name, Grimm has pointed out that in the Middle High German current when these documents appeared, “unhold(e)” was used to describe a “dark, malign, yet mighty being.” The “mightiness” attached to the word is not shared in modern German, but Grimm seems to associate it with dread or a sense of the supernatural. He suggests that by extension, the then-less-common “hold(e)” might also be “commonly used for ghostly beings.” Both words, then, would have a supernatural aura to them and differ primarily in moral valences.

Philologist and folklorist Claude Lecouteux, from his studies of the word in Early and Middle High German contexts, concludes similarly that the word “hold(e)” is related to the realm of the fairies, a world where both benevolent and malevolent beings can be found. Perhaps this reflects the dual aspect Holda shares with Perchta. Or it may reflect the opposing perspective of those revering and opposing her.

In various rewordings of the original Canon Episcopi, we find not only Holda and Unholde, but also “striga holda” and “striga unholda,” with the Latin “striga” used of witches and other evil spirits. These changes seem to document a gradual process of demonization of a Lady Holda whom followers saw as graceful and benevolent. The records of Early Modern Alpine witch-trials, which we’ll examine shortly, not only give us a clearer picture of beliefs common to the cult of Holda, but also have influenced centuries of Perchten tradition as well as contemporary customs associated with Krampus and St. Nicholas.

Herodias, Perchta, and a Hissing Head

Herodias is another ancient figure equated to Diana and Holda by Burchard of Worms and many other medieval clerics. From the 11th century onward she is frequently portrayed as a queen of witches. This biblical villain was the mother of Salome and wife of King Herod Antipas (son of the Herod responsible for the Massacre of the Innocents). She is known primarily for encouraging Salome to demand the head of John the Baptist after performing an erotic dance, a performance Herod had offered to reward with any price she asked. Not only the wickedness of this deed, but also a legend that represents Herodias doomed to forever fly in the nocturnal winds, associated her with witchcraft.

The latter is most prominently articulated in Ysengrimus, a Latin collection of fantastic tales (including fables of Reynard the Fox) probably written by the poet Nivardus around 1148. In an English version of the work, translator Jill Mann relates Nivardus’ story of Herodias, who during the Middle Ages was often conflated with Salome. Here understood as the one who had performed the dance, and smitten with John the Baptist even after his decapitation, Herodias attempts to kiss the head with unforeseen results: “The head miraculously moved away, and hissed at her with such force that she was blown up into the air and out through the skylight. Ever since then, the story concludes, she has been driven through the skies by John’s implacable anger; at night she perches on oaks and hazel-trees, and a third part of mankind is subjected to her sway.”

The legend gained lasting traction in German-speaking lands. Commenting on the medieval equation of Herodias, Diana, Holda, and Perchta, Grimm presents the myth as very much alive in his 1835 Deutsche Mythologie, remarking that winds in Lower Saxony were still said to be stirred by the whirling of Herodias’ tormented dance. In the region around the towns of Virgen and Prägraten in Tyrol, Herod’s daughter is traditionally feared as a child-stealing demon. In the Austrian state of Carinthia, she was especially dreaded, and in the town of Mölltaler, legend has it that Herodias continued her erotic dance teasingly on the ice-covered Lake Eisten. Breaking through the ice, she died and was condemned to return every year as the night-flying Perchta.

Loyal Eckhart, Ghosts, a Jug of Beer

By the mid 17th century, most of the elements of the Holda myth were in place. She was firmly connected to Diana, Herodias, and (in legends of the Venusberg) Venus. In 1663, Leipzig historian and polymath Johannes Praetorius-related a story that adds one further element. He writes of “the Loyal Eckhart” who “goes before her troop to warn any folk they encounter, asking them to remove themselves from its path so that no misfortune befalls them.”

Eckhart is a figure from earlier Germanic knightly legends grafted into the Venusberg story. In the appendix to the Heldenbuch (a 15th–16th century collection of epic poems), he is stationed eternally before the opening to Holda’s underground realm to warn away those who would enter. In the folklore of Holda’s Christmas entourage, he functions as a sort of chamberlain to the queen, a stern but helpful intercessor between mortal and immortal realms, whom Grimm compares to a psychopomp, a leader of souls. When described, he is usually a hoary figure with long beard and white staff.

Praetorius’ story of the encounter with Holda’s train continues: “Several lads of this village claimed to have seen it when they were on the way to the tavern in search of beer to bring back home. Because the ghosts were taking up almost the entire width of the road, they were pushed a little to the side with their jugs. Some of the women of this troop supposedly took the jugs and drank their contents. Struck with fear, the lads kept their peace about this, overlooking how they would be greeted back home with their empty jugs. Finally, Loyal Eckhart allegedly told them, ‘God inspired you to say nothing—otherwise they would have wrung your necks. Quick, return home and say nothing to anyone about what happened. Do this and your jugs will ever be full and you shall never want for beer.’”

Faithful Eckart, from Das festliche jahr: in sitten, gebräuchen und festen der germanischen Völker by O. Spamer (1863).

As promised, the beer remains inexhaustible until the lads give up their secret. After this, the jugs run dry.

An interesting element in Praetorius’ narrative is the motif of the jugs as cornucopia. Here the beer drunk and replenished by the phantoms should remind us of the Perchtenmilch set out on Twelfth Night. In the mythic view, the notion that the porridge was simply never touched does not enter the picture. Instead, it is a sacrifice offered the spirits, which like the beer offered Holda’s troupe, is magically replenished. Such instances may seem like minor details easily dismissed as a beer-drinker’s fantasy or an entertaining tale for children, but these are not isolated cases. In fact, they are part of a golden thread that connects Holda and Perchta to a widespread complex of myths and rituals central to the earliest trials of the witch persecutions.

Already in the 1200s, Bertold of Regensburg warns his flock against an array of pagan superstitions, referencing a number of beings resembling Holda and her horde as well as food offerings left for them. He writes: “You should not believe at all in the people who wander at night (Nahtwaren) and their fellows, no more than the Benevolent Ones (Holden) and the Malevolent Ones (Unholden), in fairies (Pilwitzen), in nightmares (Maren, Truten) of both sexes, in the Night Ladies (Nahtvrouwen), in nocturnal spirits, or those who travel by riding this or that: they are all demons. Nor should you prepare the table anymore for the Blessed Ladies (felices dominae).” The table here, of course, refers to food offerings.

The very earliest explicit mention of Perchta occurs in a 1350 tract entitled Mirror of Conscience, mentioning such a table and condemning those “who, on the night of Epiphany, leave food and drink upon their table so that all shall smile upon them over the coming year and good luck will grace them in all things … Therefore also sinning are they who offer food to Percht …” And again in 1468, in the Bavarian Thesaurus Pauperum, we find a condemnation of the “idolatrous superstition of those who left food and drink at night in open view for Abundia and Satia, or, as the people said, Fraw Percht and her retinue, hoping thereby to gain abundance and riches.”

The idea of ghostly beings at once consuming and replenishing food during nocturnal visits is also found further west in Switzerland. There the folkloric cousins to Perchta’s train were known as the “Blessed Ones” (sälïgen Lütt). In an account written around 1600 by Renward Cysat, a city clerk of Lucerne, they are described as the “souls of people who died violent or premature deaths, who must wander the earth until the day that fate has fixed for their passing; these folk are friendly and kind, and enter the homes of those who speak well of them at night, cook, eat, and then leave again, but the amount of food does not diminish.” Elsewhere Cysat quotes a peasant woman speaking of the Blessed Ones who makes clear that these spirits share Perchta’s concern with domestic order. “Among other idiocies,” Cysat writes, “she said that these folk that roam the night become irritated when the kitchen has been left untidy. “

Witch from Gruabtoifi Saalfelden, Austria. Photo ©Günther Golliner.

Another element worth examining in Praetorius’ story has to do with the secrecy surrounding the magical filling of the jugs. Sharing the secret of this boundless source, of course, could lead the greedy to seek out encounters with Holda and her host. Preventing this danger is precisely why Eckhart had been added to the myth, why he goes before the horde to warn away onlookers, and why he guards the gate to the Venusberg.

Even to look upon the phantoms was regarded as a great danger, and in some regions, those caught unawares by Holda’s passing were advised to throw themselves face to the ground with arms outstretched in the shape of the cross. Even where Eckhart is not named, there is often an anonymous forerunner posted before the horde to offer similar warnings. Likewise Perchta, according to one tale, blinded for a year an overly curious peasant who dared to peek at her through a keyhole. Already imperiled for having glimpsed the specters, the boys in Praetorius’s story, as Eckhart tells them, would have surely lost their lives had they dared to speak to the ghosts. The jugs’ magic can only work if hidden, not if made manifest.

The terror of contact with the dead, and the notion that interaction might somehow be mortally contagious seems intuitive. Yet there is also something confusing in these Holda narratives—namely the restyling of the Hörselberg, a grim abode of lost souls, as the Venusberg, with its endless feasting and erotic pleasures.

Some of this may be due to the early modern era’s idealized fascination with classical paganism as a playground outside purview of the Church. As an already ambivalent figure both hold and unhold, as a mother of both cradle and grave, perhaps Holda’s identification with such diverse and contradictory figures as Venus, Sibyl, Herodias, and Diana becomes more understandable. Also entering into the Venusberg legends may be a bit of Christian myopia and envy, blurring diverse and contradictory pagan figures into a single enticingly unchristian fantasy figure associated with erotic indulgence.

As a realm of pleasure from which there is no return or escape, the Venusberg has many parallels in folk tales and legends. Whether the gold-filled subterranean halls of dwarves, enchanted fairylands, or a kingdom under sea, these lands of no return have been understood by many folklorists as representative of death and eternal reward. Entering this realm, the soul may never again participate in mortal life, but instead partakes of immortality and the immortals’ power to know and control man’s fate.

This is the sort of contact sought by the necromancer, who by calling on the dead obtains hidden knowledge, boons, or control over destiny. The food offering left for Perchta’s company, like the necromancer’s invocation, is a magical summons. It draws in and feeds the dead so that the dead may feed the living. The impoverished mortal, through this small offering, can connect with immortal abundance. The magically replenished beer and Perchtenmilch, in their small way, illustrate this ritual transaction with the dead.

Despite the danger implicit in mortal contact with the immortals, there have been many who hoped to gain magical powers by seeking out Holda in her realm. One account of this is provided in records from a 1497 trial of the witch Zuanne (Giovanni) delle Piatte in the Italian town of Val di Fie Fiemme in German-settled South Tyrol. Previously accused of possessing magical crystals and “many signs and diabolical formulas in the German language,” delle Piatte claimed to have been allowed to visit Herodias’s home in the Venusberg (“el monte de Venus ubi habitat la donna Herodiades”) where he encountered “a white bearded old man called ‘loyal Eckhart.’” Adopted into the supernatural society within the mountain, delle Piatte, along with select mortals, feasted and drank, and enjoyed the ability to undertake magical flights around the world during the Christmas Ember Days.

Similarly, in a trial held in Hesse in 1630, the accused, Diel Breull, claimed to have woken from sleep within the Venusberg where he encountered “Fraw Holt,” enjoyed feasting and drinking, and was granted visions of the dead seated in purgatorial fire. Like delle Piatte, he was adopted into Holda’s troupe and subsequently transported to the Venusberg four times each year during the Ember Days.

Renward Cysat’s informants from 17th-century Lucerne offered similar stories of adoption by and travels with the “Blessed Ones.” The wife of an acquaintance of Cysat’s claimed these trips into immortal realms granted her visions of things “that no one in our fatherland knows of yet.” When asked if her husband knew of these fantastic flights, “she answered no, because her body remained lying in bed.” As these visionary trips repeated on set calendric dates, they were understood to be more than randomly occurring dreams, rather they were purposeful excursions of the soul, which, according to medieval belief, travels out from the body in sleep.

At the beginning of Chapter One, I mentioned traveling on my way to Gastein through Italy’s Friuli region, where important 16th and 17th-century witchcraft trials related to our story had taken place. The accused, in this case, were members of the benandanti (“good walkers”), a visionary cult whose members saw themselves as the benevolent opponents of malevolent witches (malandanti) and claimed to do battle with these witches in spirit form. At stake in these battles was said to be the fertility of the fields and welfare of their community. Like Diel Breull arriving at the Venusberg in sleep or Cysat’s acquaintance traveling with the Blessed Ones in dreams, the benandanti claimed to conduct their excursions against the witches on the Ember Nights while their bodies lay in a state of trance.

The female benandanti also claimed that in their nocturnal travels they celebrated feasts and dances like those within the Venusberg. In trial records one of the benandanti reported “bowing her head to a certain woman called the Abbess, seated in majesty on the edge of a well.” Given that the Friuli region had been settled by Germanic tribes, the Abbess and her well might remind us of Holda and her sacred pond. Those who followed that Abbess did so in spirit, like certain travelers to the Venusberg.

Historian Carlo Ginzburg, in The Night Battles: Witchcraft and Agrarian Cults in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries, regards the benandanti’s Abbess, like Holda, as belonging to a family of nearly identical cult figures found throughout the Alps, northern Italy, and beyond. Typical of spirit travelers following these figures, the benandanti visited homes by night, slipping in to drink wine from casks in the wine-cellars, leaving these, like the jugs of beer, magically replenished. Even more significantly, Ginzburg regards the spiritual opposition of the benandanti vs. malandanti as a likely reflection of the Schönperchten-Schiachperchten duality, a notion I’ll later discuss.