Though it’s hardly a feature of the modern horror film, up until at least 1860, according to German Folk Superstitions of the Present, Christmas and werewolves went hand in hand. The seasonal fear of these beasts was so great that simply to utter the word “wolf” between Christmas and Epiphany (or even during the entire month of December) was to put oneself at risk. To avoid being “torn apart by werewolves,” so goes the superstition, one should replace the word “wolf” with “enemy,” “pest,” or some other circumlocution less likely to summon the beast. Not only was this (along with the summer solstice) one of the primary times for werewolf transformations, but in German-speaking lands (as well as in Italy, Romania, and Russia), to be born on Christmas Day could be considered an affront to Christ and thereby result in one being cursed to life as a werewolf.

It was not just the werewolf that haunted the snowy forests and mountains this time of year. Along with witches and spirits of the dead led by Perchta or Holda, the season brought encounters with the Drud, a sort of night hag that smothered and sickened sleepers and could only be repelled by the Drudenfuß, or pentagram. In Alpine regions, families listened for the eerie cry of the demonic goat-like Habergeiß. In marshes, travelers feared the Nebelfrau (“mist woman”) who seduced travelers from the safety of their paths. Impending death might be announced by the arrival of the Seelvogel (“soul bird”), whose claws transported the doomed to the other side. The nocturnal forests and moors swarmed with spirits: the Moosweiberl (“moss woman”), Holzleute (“Wood Folk”), and the Schratzln (forest goblins). Even places of industry were endangered by malevolent beings this time of year. The Melhweibl (“flour woman”) could drag the miller into the grinding gears of his mill, and the Durandl, a sort of goblin haunting the glowing depths of the glass furnace, could emerge to destroy the day’s work or even set the foundry ablaze.

Historical and semi-historical figures too joined the season’s ranks of threatening ghosts. Frightening travelers in the Lower Bavarian Forest was Woidhaus-Mich, a monstrously large and powerful cowherd said to occasionally devour the raw flesh of his own animals, dispatching them with a club made of a dried bear claw. And in the same region, chatelaine Maria Freiin of Castle Rammelsberg lived on as the witch Wecklin, condemned to dance in burning slippers during the Twelve Nights of Christmas because she once used her own slipper to beat to death a child who’d spilled some milk. Even the “Forest Prophet” Mühlhiasl of Apoig, after his death in 1805, became a sort of seasonal phantom, thanks to his eerie prophecies of human extermination that caused him to be refused burial on consecrated ground.

Even the saints themselves twisted into sinister forms during the month of December. On St. Lucy’s Day, the shrouded Lutz or Lutzelfrau once threatened children with evisceration or drowning, and on St. Thomas Day, “Bloody Thomas” stalked the forest with a gore-drenched hammer. We’ll examine these characters further in a bit as they represent the same sort of monstrous inversions of a Catholic saint we find on St. Nicholas Day with the Krampus.

Of all the terrors unleashed during the nights around Christmas, the most widespread in German-speaking lands were those ghostly processions previously mentioned—both the solemn train of souls led by Holda or Perchta as well as the stormier apparition of the Wild Hunt or Furious Army.

Broadly amalgamating and sometimes blurring together elements of hunting and diabolic hunters, lost souls, and slain warriors, stories of ghost hordes are widely dispersed across Central Europe, Scandinavia, the British Isles, and even North America, where the spirits appear in cowboy legends, and made their way into the 1940s country-western ballad “Ghost Riders in the Sky.”

The terms “hunt” and “army” can sometimes be misleading. The prey hunted by the Wild Hunt, if one is actually hunted, is rarely seen or specified. “Hunt” may be understood as merely describing the quality of the apparition’s movement—a racing stampede of figures chasing one after the other. Likewise, the word “Heer” (army) can also simply mean “a great number,” as in “horde,” and needn’t always designate a specifically military assembly. This usage is evident in a 1508 sermon by the German preacher Johann Geiler von Kaiserberg in which he characterizes this army or horde not as fallen soldiers, but otherwise:

You ask, what shall you tell us about the Wild Army? But I cannot tell you very much, for you know much more of it than I. This is what the common man says: those who die before the time God has fixed for them, those who leave on a journey and are stabbed, hanged, or drowned, must wander after death until there arrives the date that God has set for them … Those who wander are especially active during the Lenten days, and first and foremost during the lean times before Christmas, which is a sacred time.

Those who have died before their time could also describe the spirits led by Holda, and in a more limited way Perchta’s Heimchen who did not live to be baptized. Slightly more martial, and specifically mentioning dead soldiers, is this account from 1516 by Strasbourg historian Jacques Trausch:

At night, the Army hastens through the fields, playing drums and fifes, and also it travels through the towns, its members carrying lights and making loud cries. Such ghosts number sometimes fifty or eighty and even one hundred or two hundred. One carries his head in his hands, another carries a cross or sometimes an arm or a leg, depending on the manner in which each found his death in battle. They carry candles that cast enough light so that it is possible to recognize who they are and if they died in war or elsewhere. A man always preceded them, ceaselessly shouting, “Make way, make way, lest you suffer!”

The unnamed forerunner is clearly comparable to Loyal Eckhart, and it should be noted that the ghostly horde here is not exclusively made of soldiers, but those who “died in war or elsewhere.” The warriors among them are not in the throes of that battle fury evoked by the term “Furious Army.” All of this points to the difficulty of conceptually sorting such apparitions. Names like “Wild Hunt” or “Furious Army” rarely represent clear-cut categories, so for the sake of simplicity, I will occasionally refer to the collective spectrum of ghostly processions as “The Wild Hunt.”

To understand these apparitions, we must examine sets of intermittently overlapping traits. One of these is the perceived function or mission of the phantoms. This might include hunting or making war, heralding a dire event, bestowing blessings, or participating in ghostly revels. Christianity often reshaped this essentially pagan phenomenon, and displaced and departed souls began to be portrayed either as damned souls condemned to wander, or as demons. Or demons might be mingled with the damned as their torturers driving them onward.

Lo Stregozzo (the Witches) by Marcantonio Raimondi and Agostino Veneziano (ca. 1520). Some historians have seen this engraving as a depiction of the Wild Hunt.

The location of the sightings may also be a differentiating factor. Perchta’s company, or the Swiss säligen Lüt, for instance, are said to move through towns and visit homes, while the Wild Hunters naturally appear in wilderness areas. The Furious Army may appear either in areas populated or wild. Most apparitions appear at night, but there are occasional daytime exceptions to the rule.

Where there is no direct interaction with mortals, the company passes through at some elevation, either high above in the clouds, or quite typically, floating several feet above the ground. As these ghosts frequently remain invisible, eerie sounds may be all that characterizes the experience. Witnesses may find themselves enveloped by the sound of sweet otherworldly music, the clamor of a passing army, or the barking of invisible hunting dogs. Unsurprisingly, the sound of wind howling through Alpine peaks and ravines is often mentioned and said to assume a supernatural quality betraying the passage of spirits.

The Norse Wuotan (Wotan/Odin) is particularly associated with these winter apparitions. As a deity concerning himself with death and warfare, he is naturally connected with the Furious Army, and serves as its most frequently named leader. His traditional wolf companions, Geri and Freki, might be associated with the ghostly hunting dogs found elsewhere. As the phantoms usually appear amid the clouds, Odin’s role as god of the storms and winds further associates him with these apparitions.

Throughout that region, particularly in the German state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, east of Hamburg, the apparitions were reported with particular frequency. Around the town of Rostock, it was called the “Wohl,” a name equated with “the Wild Hunt, also called the Furious Army” (italics mine) in an article by one Professor Flörke, writing for his local paper in 1832. He writes:

Our agrarian laborers, who seek to profit from the cool of the evening air to bind the rye, were so terrified by the Wild Hunt they would barely dare go into the fields, shivering all the while. First, they heard the baying of hounds, which then mingled with the fairly harsh voices of men and others that were fairly sweet. They saw fires that passed rapidly through the air, then, if they did not flee, the entire army paraded before them in a terrifying din made up of barking, instruments that sounded like hunting horns, and panting.

Detail of Åsgårdsreien (Asgard riders) by Peter Nicolai Arbo (1872). A Scandinavian depiction of the Wild Hunt.

Professor Flörke equates the Wohl with Wuotan, he says, thanks to the example of “a pious preacher,” who’d convinced him, “that this was nothing other than the devil himself accompanied by several fallen angels, who took pleasure in frightening people. The devil, he said, took the form of Wuotan, the old pagan idol.” Though most common in the north, Wuotan also plays the role of Wild Hunter in Germany’s Alemannic regions further south, in Swabia, and in Switzerland, where the apparition is know as Wuotis Heer (“Wuotan’s Army”).

While Wuotan’s association with the Furious Army or Wild Hunt is undeniable in the areas mentioned, there has been a historical tendency among German writers to universalize his importance and interpret any folkloric motifs in terms of the Nordic pantheon. In the case of those Alpine regions where the Perchten and Krampus mythology evolved, though, connections with Odin are not explicitly present, and historians seeking these may overlook the obvious possibility of influence from non-German-speaking but geographically closer regions. The myth of nocturnal sightings of phantom hosts, are, after all, present not only in countries surrounding the Alps but also extend geographically and chronologically to the classical world, where stories of ghost armies are mentioned by Greek and Roman writers such as Herodotus, Tacitus, or Ovid, who writes of an omen heralding Caesar’s death, describing “the rattling of weapons in the black clouds, the sound of terrifying trumpets and horns in the sky.”

This emphasis on the Nordic stems, in part, from Jacob Grimm, German Romanticism, and the desire to forge a language-based cultural identity prior to the 1871 formation of the German state, a tendency further cultivated by late 19th-century völkisch (from the German word for “folk”) movement searching for ancient pagan roots of a pan-Germanic culture. All of this reached fever pitch in the Third Reich, with Wuotan’s association with war providing a mythic grounding for Himmler’s fantastical worldview. His occult initiatory order, the SS, drew inspiration from an ancient Germanic tribal model, namely blood bonds between warriors and a leader embodying Wuotan. The fury (Wut) of the Furious Army (Wütende Heer) was etymologically linked to Wuotan and celebrated as the ecstatic state in which Viking Berserkers went to war. While not consciously referencing Third Reich ideology, this tendency occasionally surfaces today on websites and in articles proposing specious connections between the costumes of the Perchten and the wolf and bear pelts or animal masks worn by the Berserker.

In Scandinavian countries, Wuotan is even more prominent. The Wild Hunt in Norway, for instance, is called “Oskoreia,” a corruption of “Åsgårdsreia” (“riders of Åsgård”). Witches and trolls might join these Julereia (“Christmas riders”) as well as the spirits of the dead. Departed ancestors might be envisioned as part of this company, and to insure their comfortable passage during these nights, a meal and ale might be set out, a fire might be left burning for their warmth, candles to light their way, or even sometimes a warm bath might be drawn.

The figure of Wuotan in the Scandinavian Wild Hunt does not inevitably represent some sort of archaic survival of pagan belief. In an explicitly Christian tale from Swedish, for instance, the Wild Hunter Wuotan is identified as a nobleman who defied Church law by hunting on the Sabbath and is therefore doomed to hunt throughout eternity. An even later incorporation into the myth occurs in Denmark, where Odin does not show up as the wild huntsman until the 18th century.

Less aggressive than the hunters or warriors associated with Wuotan are the Night Folk (Nachtvolk) and Night Throng (Nachtschar) who appear especially around Christmas in the Alpine area where southern Germany, western Austria, and northern Switzerland meet. These two names designate similar groups, and some regional sources do not differentiate, also using the terms “Death Folk” (Totenvolk) or “Death Throng” (Totenschar) interchangeably. As these specters are not hunters or warriors, they distinguish themselves by moving in a slower procession, and on foot. Despite this, they are inescapable, and they may inexorably follow given paths. Obstructing their progress over these routes is dangerous. Doors on opposite sides of a house must sometimes be left open to create a ghostly throughway, and tales are told of havoc wrecked if houses are not thus readied, or of houses blown down if constructed on a route the spirits follow. The same is also often said of obstructing the Wild Hunt.

A few tales of the Night Folk from a volume of Austrian legends collected in 1911 illustrate more of their characteristics. The first is told of a wanderer in Eastern Austria’s Vorarlberg region:

On a moonlit night, a farmer from Montafon arrived in a nearby ravine and sat down upon a stone to rest, and drawing out his mouth harp, he played to pass the time.

Then all at once, the Night Folk appeared in a long procession moving through the ravine. A shadowy figure stepped up to the farmer and said, “Hear now, if you choose, I can instruct you to play so beautifully, the pine cones will rise and dance round about us.”

“That would please me,” replied the musician.

Scarcely had the lessons begun, when from the throng emerged a woman who drew the shadowy figure back into the crowd, whispering to him: “Come, this one is not worth your time. Only this morning, he has taken holy water.”

The lonely wanderer crossed himself, realizing with horror the danger he had so narrowly escaped.

Bestowing supernatural musical ability is a particularly distinctive trait of the Night Folk. As with the shadowy figure in our tale, they are usually described as black silhouettes, or may be dressed in black like priests or monks. They produce striking music, sometimes described as “heavenly,” or “as if the angels were playing,” but often as a tool of seduction for those they would abduct from among the living. They may hold nocturnal revels similar to those of the witches, usually in isolated wilderness areas, but occasionally closer to areas of human habitation, or even during the day, as in this tale from the above-mentioned volume:

Once, however, the Night Folk appeared in the tiny hamlet of Walsertale during daylight hours to hold a merry feast. While mass was being said in a nearby church, they snatched a farmer’s finest cow from the stable and hurriedly slaughtered and consumed it amid dancing, shouting, and the sweet sounds of stringed instruments. To the children who had remained in the house, the Night Folk kindly gave some of their meal, but warned them not to break or discard the leg bones. After the meal, all the bones were collected but one, which despite all the searching could not be found. Then they wrapped the remains in the skin of the slaughtered animal and declared that because of this, the cow will limp home. When the Night Folk had withdrawn, the living cow again stood in its stall as before, but thereafter dragged one of its feet.

This sort of slaughter, consumption, and restoration of a living creature, dubbed the “Miracle of the Bones” by historian Wolfgang Behringer, is a common feature in accounts of the Night Folk. As we’ve seen, it is also figured into tales of witchcraft revels in Tyrol, usually in reference to butchered livestock but also to human children who are eaten. Behringer regards this re-animating “Miracle of the Bones” as symbolizing “the most extreme form of benevolence,” providing “the best thing in the world: life itself.”

The benevolence of the Night Folk, however, was not so evident in the Swiss cantons of Glarus, St. Gallen, and Graubünden, where the ghosts behaved in a less civilized manner, did not play music, tended to blind or abduct witnesses, and often through their appearances heralded death or epidemics. Seeing those still alive amid the throng of departed souls never bade well, as in this tale collected by the folklorist Theodor Vernaleken in the canton of Graubünden in 1858:

Midnight is the hour when the Death Folk move about, at their front, the bony figure of Death leading with his violin all who will die within the year. At the time of the plague known as the Black Death, a man in the Churwalder Valley heard by night a soft music passing close. He leapt up, and throwing one leg into his pants, rushed to the window, flung back the curtains, and saw the Death Folk. Among them were many of his acquaintances, and there at the end of their train, with pants pulled over one leg only—he himself! Pale and rigid with terror, he sank back, knowing that he would be the last of all to die of the plague. And that was how it happened.

Because it was advisable not to look upon any class of these wandering specters, and because—from an empirical perspective—sound divorced from vision left more room for the play of imagination, what was heard of these apparitions was often featured more prominently than what was seen. A peculiar sound almost always anticipated the troupe, which itself might remain invisible. It is often described as musical. At times it was the martial sounds of drums and pipes, at others, more ethereal. Or it may have come as “a droning murmur,” “a strange hum like the buzzing of bees,” a “song sounding like a Psalm,” or “the rattling of bones and many voices in prayer.” It could build to a crescendo described by one storyteller as “the music of a thousand instruments, followed by the crash of a storm breaking through the oaks of the forest,” building finally to the noise of “a great rolling black coach, in which hundreds of spirits sit joined in wondrous song.” The sounds accompanying the host could also predict the future. Should the ghosts’ “appearance signify a good year, it brings music,” and “if war or sickness await, a discordant noise accompanies it.”

In the case of ghosts recognizable as soldiers, the leader can be Wuotan or also a historical warrior, as is the case with Charlemagne, who rises from within Austria’s Untersberg mountain to lead his ghostly army at the time around Christmas. In the case of a phantom hunting party, particularly in Thuringia, the leader can be Holda, as we’ve seen, thanks to her association with the huntress Diana. Further north toward Scandinavia, the rider can be the tragic and vengeful Gudrun (Kriemhild) of the Germanic Nibelungen legends.

Local legends may also position a cursed nobleman as the Hunter. In the former northeastern German province of Pomerania, it was Count von Ebernburg who was doomed to hunt forever. Riding out one Sunday morning rather than attending church, legend says the count found two strangers in his hunting party, one angelic and the other devilish. While the angelic rider counseled Ebernburg to return to church services, the wicked one mocked this and was soon joined by Ebebernburg in his ridicule. Eventually the strangers vanished, and soon enough, the riders found their horses running not on the ground but with hooves in midair as the whole party was swept into the sky where they still ride today.

More commonly, particularly in Westphalia and Lower Saxony, the hunter named is Hackelberg (sometimes Hackelbärend, Hackelblock, etc.). Like Count Ebernburg, he is often cursed to wander thanks to his disregard for the Church. During the Twelve Nights of Christmas, or during thunderstorms, the sound of his hunting horn may be heard, and amid a pack of hellhounds, the figure may be seen upon a black steed with smoke trailing from glowing nostrils. Sometimes the party is preceded by Tutosel, an owl, inhabited by soul of a nun, whose dreadful singing in life approximated the hooting of that bird.

Legends often mention female forest spirits as the prey of the Wild Hunter, either the Holzweibl (“wood woman”) or Moosweibl (“moss woman”), both of whom are said to be diminutive, dressed in moss, leaves, or other vegetation, and generally friendly to man. Some scholars have suggested that the image of this hunt is suggested by the wind (associated with the Wild Hunter) chasing leaves or woodland debris across the forest floor. Woodcutters, sympathetic to the plight of these kindly forest beings, would sometimes protect them from the Wild Hunter by marking trunks of felled trees with three crosses, thereby rendering the stumps safe havens from the phantom huntsmen.

Odin as the Wild Hunter, from Die Götterwelt der deutschen und nordischen Völker (1860).

Stories of these forest folk pursued by the Hunter are particularly prevalent in the Thuringian Forest. In Germany’s Vogtland, a region straddling Thuringia, Bavaria, and Saxony, on the Czech Border, the Moosweibl and Moosmännel (“moss man”), are important in Christmas tradition. During the Twelve Nights, they are said to flee the inhospitable frozen forest and seek the warmth of human habitation. Handmade representations of the figures covered in moss and holding candles are still traditional in Vogtland homes during the holiday. These mossy figures, which have become popular beyond the Vogtland, originated in the second half of the 19th-century as an inexpensive handicraft item poorer rural folk could create and sell in bustling Christmas markets.

The suffering of those who fail to treat the Wild Hunter with due respect is another popular theme in the folklore. One tale tells of a woodsman who hears the Wild Hunter pass and impudently imitates him, crying “Ho, ho, ho.” Another has the woodsman calling out after the Hunter asking to join his hunt. In both cases, their disrespect is rewarded the following morning as they find a grisly gift—a portion of a slain Moosweibl nailed to his stable door. In another tale related by Grimm, an overbold carpenter is startled when “a black mass came tumbling down the chimney on the fire, scattering sparks and brands about the people’s ears: a huge horse’s thigh lay on the hearth, and the said carpenter was dead.” Another legend warns that the impertinent will be devoured by the Hunter’s dogs.

Riding the winds during the nights around Christmas, the Wild Hunter in Switzerland goes by the name Türst. Legend most famously associates him with Mount Pilatus near Lucerne, but he also appears elsewhere and in regional variations. The specter is known by the sound of his hunting horn and the eerie barking of his three-legged hunting hounds led by a one-eyed canine. In some regions, this pack is a monstrous hybrid of dog and swine. In other regions, Türst himself transforms into a dog for the hunt, or turns those who impede his path into dogs compelled to join his ghostly party. Livestock whom the phantoms passed by would scramble, go mad in their stalls, or cease giving milk.

As a spirit of the mountains and wilderness, Türst functions as a sort of gamekeeper, and his hunting horn has the power to summon any wild creature. In some tales, Türst is also master of the goblins who reside on Santenberg mountain near Lucerne, and together they were said to protect a unicorn living amid the crags. As spirit of the wind, Türst, like other embodiments of the Wild Hunter, would blow down structures not left open to his passage. As spirit of the storm, however, his power was especially feared and gave rise to the erection of Wetterkreuze (weather crosses) to calm or repel his destructive force. One such cross once stood on the Santenberg with the inscription, “Here hunts Türst.”

Sometimes the hideous witch Sträggele accompanies Türst as his wife. Said to abduct or eat children, she was used as a bogey to frighten misbehaving children. Like Perchta, she could also have a kindly side, and was likewise associated with spinning and the Twelve Nights. Sträggele and Türst were also sometimes joined by the Pfaffengälern, a mysterious wild phantom with flaming eyes.

The Twelve Nights, the Rauhnächte

Apparitions that have thus far been mentioned as occurring “around Christmas” specifically tend to fall within those twelve days between Christmas and Epiphany. For most Americans, these Twelve Days have little significance beyond partridges, pear trees, and a vague notion of extended merriment in picturesque old England. But in the folklore of German-speaking lands, when “the Twelves” (die Zwölfte”) are counted, it’s not a matter of days but uneasy nights. The period is regarded as a sort of calendric limbo in which one year dissolves into the other, and the otherworldly leaks into the mundane. In Germany’s Vogtland, it’s referred to as the “between-nights,” the “inter-nights” or “under-nights.” In other regions it’s the Losnächte (“oracle nights”) because fortunetelling is practiced then. Glöckelnächte (“knocking nights”), is yet another expression arising from the custom of groups of young people going out by night and mischievously thumping doors and windows and demanding treats.

The most common name, however, is the Rauhnächte (singular: Rauhnacht). The etymology of the term is much debated. Some scholars suggest it originates with the Middle High German word rûch for “hairy,” referring presumably to fur-wearing performers, like the Perchten, who roamed these nights. Others believe the term related to the word for smoke, “Rauch,” thanks to the practice of censing homes, stables, and barns during these nights to drive off evil influence. In some regions, the name Rauchnacht (“smoke night”) rather than Rauhnacht is used, but this may be a more modern development. The most significant nights within the twelve are Christmas Eve, New Year’s Eve, and Epiphany’s Twelfth Night. In other regions, however, the twelve-day period is shifted to end on the New Year, and begins instead on the eve of St. Thomas Day (December 21) instead of Christmas. While not technically a Rauhnacht or within the twelve, St. Lucy’s Day (December 13) is also often associated with similar beliefs and practices.

Exactly when these nights acquired their significance is unclear, but the notion of this as a time of supernatural possibility seems to consolidate at some point during the Early Modern Period. Some scholars have suggested that the 12-day difference between lunar and solar years point to much older origin in attempts to synchronize ancient Germanic or Celtic lunar calendars with the Roman solar year, but there is no clear evidence for this in the historical record.

While the Rauhnacht traditions are historically strongest in German-speaking lands, related beliefs and practices are scattered throughout Europe and Russia with Epiphany fortunetelling being the most common.

A surprisingly large number of regionally diverse and sometimes contradictory superstitions cluster around the Rauhnächte. Along with the notion of opening doors or windows to facilitate passage of the Wild Hunt, clotheslines or hanging laundry were not to be left out at night for fear of entangling flying ghosts. On New Year’s Eve, it was specifically the back door that was to be opened, because only through this door could good luck arrive; all others were to remain shut. Doors were to be closed quietly as slamming doors on New Year’s Eve caused lightning strikes in the coming year. Washing, baking, and other chores were at least partially restricted during the period, but clean homes were to be maintained as dirt and disorder attracted malevolent spirits. Garments missing buttons needed to be mended before the Rauhnächte, lest financial hardships result. Neither hair nor nails were to be trimmed as doing so could cause headaches and inflammation in the fingers. Spinning wheels, wagon wheels, or geared machines were to be stopped as only the Wheel of Fortune was to turn on these portentous days.

Women and children would not to go unescorted after sunset for fear of the Wild Hunter, roving spirits, witches, and werewolves. But those who did venture out might be rewarded with wondrous sights. At midnight on Christmas Eve, running brooks turned to wine, bees buzzed and swarmed in the frigid air, and standing under an apple tree, one might look up and see the heavens open. At that same hour, animals spoke in their pens, stalls, and stables. Their utterances could reveal the future, but none could share these secrets, as death would quickly overtake any who witnessed the miracle. During the Rauhnächte dog barks heard in the distance acquired special meaning; those you heard following a private thought confirmed the truth of that thought; those heard after midnight presaged a coming death. Domestic animals might also use the gift of speech to speak to the Hausgeist, the protective spirit or fairy resident in each home. Should the animal complain of ill treatment by its master, the Hausgeist would ensure retribution. These domestic spirits were particularly active during this time, and families did well to placate them with small gifts set out overnight.

A number of Christmas Eve customs surviving into the 19th and 20th century recall seasonal food offerings left for Frau Perchta centuries before. On Christmas Eve in Lower Bavaria, sausages would sometimes be prepared to break the fast after midnight mass, with a portion of these set aside for the departed. When on Christmas morning the food appeared untouched by specters, it was donated to a needy person promising to pray for the dead and thereby offer sustenance in another form. Elsewhere, the spirit visitors were said to be the Holy Family. In Tyrol, milk was set out for the Christ Child and his mother after midnight mass, and elsewhere in Austria, candles were set out to light their way. In Northern Germany too, lights were left burning and food was left on tables for the Virgin and the angels.

The period of the Twelve Nights lends itself to prognostication as events of each day can be correlated with each of the coming twelve months. One method of prognostication used an onion split into twelve bowl-shaped parts. Each was marked with the name of month and sprinkled with salt. In the morning, the amount of moisture found in the hollow of each slice showed how wet or dry each month would be. Generalized predictions for the entire year could also be inferred from weather observed on New Year’s Day. High winds announced a troubled year; clear skies, pleasant times; frosted windowpanes or heavy snow, a year of healthy profits. Vintners hoped for clear skies, anticipating a robust harvest and superior grapes. Epiphany’s sunny skies heralded a peaceful year for all.

For unmarried women, the identity of one’s future lover or bridegroom was best discovered during the Rauhnächte. Swabian women drew sticks at random from a woodpile; long, short, straight, or crooked, they foretold similar qualities in future mates. Women in Baden-Württemberg sometimes formed a circle around a blindfolded gander, waiting to see who would be approached first by the animal and therefore next to marry. Tyrolean women put an ear against the side of a warming oven, straining to make out prophetic sounds; music foretold a coming wedding, while the sound of bells represented a death knell for the listener. A young woman who waited at the crossroads during a Rauhnacht might encounter an apparition of her future bridegroom, but she must resist the temptation to address him for this would mean her death. Death or exile in the coming year could be predicted by a curious ritual involving a slipper thrown against a door; however it landed, its toe pointed to the individual who would depart within the coming year.

While most all of these superstitions have long been forgotten or fallen into disuse, one method of fortune-telling long associated with the Rauhnächte is still practiced, though usually in a more skeptically playful spirit. This is Bleigießen (lead-pouring), divination from shapes formed by molten lead cooled in water. One of the many tools of prognostication employed by Roman augurs, this technique, known as Molybdomancy, spread via imperial expansion throughout Europe. While otherwise unused today, it has been retained as a New Year’s Eve recreation in Germany, Austria, Switzerland, and Scandinavian countries. As originally practiced (on any of the Rauhnächte, not just New Year’s Eve), leftover bits of lead used in farm repairs would be melted and dropped into water. Not only the shape of the solidified metal but the shadow it cast could be scrutinized for clues.

Of typical concern might be the trade practiced by a future bridegroom, so blobs would be scrutinized for resemblances to a tailor’s shears, a miner’s pick, or blacksmith’s hammer. Later, Christmas tree tinsel, in the days it was still made of lead, was melted down. Today commercially produced kits are seasonally available, and include, along with spoon and lead pellets, a prepared guide to aid interpretation. Though still quite common, lately the substitution of wax for lead has been promoted due to certain degrees of toxicity associated with the use of lead.

As mentioned, censing the property to provide protection from evil is one possible source of the name Rauhnacht/Rauchnacht. Though far more rare than the practice of Bleigießen, this custom has not completely died out in rural Alpine areas, though is now conducted more as a matter of family tradition than for spiritual safekeeping. This was not the case, however, in the 19th century, when even in urban areas such as Munich, censing of commercial sites and office buildings was regularly carried out. In its current survival, Ausräuchern only exists as a Twelfth Night custom, but formerly the practice was also associated with Christmas Eve, and or on Thursdays throughout Advent.

Even outside rural areas where Ausräuchern is practiced, the custom of burning incense at Christmas survives in the contemporary popularity of figurative wooden incense burners (Räuchermännchen or “smokers”) sold at German Christmas markets alongside nutcrackers and other ornaments. Usually carved in the Erzgebirge Mountains, a region famous for its handcrafted wooden toys and Christmas decorations, the Räuchermännchen typically take the shape of rustic lederhosen-wearing peasants, night watchmen, hunters, or other traditionalist figures. To some small extent, the practice of Ausräuchern has also been rediscovered in certain New Age quarters, where it is naturally reframed in terms far removed from the folk Catholicism of its origins.

Traditional Ausräuchern is carried out with a small pan or pot filled with burning charcoal and frankincense. In earlier times, a mix of juniper berries and herbs selected for their magical properties might also be used. The head of the household carries this through the home, barn, and animal pens accompanied by the eldest child, wife, or servant who sprinkles holy water along the way. Ideally this would be Dreikönigswasser (Three Kings’ water) blessed during the Epiphany mass of the previous year. As the party moves about the property, smoke is blown from the censer to the four directions, and prayers are offered. Each cow is individually censed and sprinkled with holy water, and specific prayers are offered for their protection from disease and epidemics. After their normal feeding, the cattle might also receive consecrated bread, cabbage, salt, and water. Before fumigations are complete, any headgear in the house is set over the pot to collect the smoke, thus making its wearer immune to headaches. Feet or shoes may be similarly smoked for safe travel. After all this has been done, the censer is left overnight in the herb garden to provide a final blessing there as it cools.

The initials of the Three Kings (Kaspar, Melchior, Balthasar) chalked over a door on Epiphany, 2012

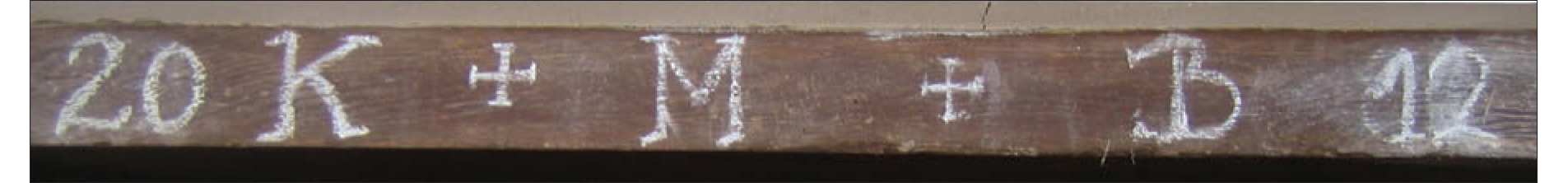

As well as fumigating all corners, above all doors, and even the pigsty, an inscription is traditionally chalked for further protection over all who enter. Usually, this took the form of the letters K, M, and B joined with crosses and sandwiched within numerals representing the years, so for 2016: “20 + K + M + B + 16.” The letters are said to represent the Magi’s traditional names: Melchior, Caspar (German: “Kaspar”), and Balthasar. Sometimes the letters may be altered as C + M + B, more recently said instead to represent the Latin “Christus mansionem benedicat” (Christ bless this house) or K + M + B, inserting the Greek Kyrios (“Lord”) into the formula. The inscription is to remain over all doors until the following Twelfth Night. Sometimes, a pentagram may also be drawn over animal pens as additional insurance against the Drude and other evils.

Historically, the practice seems to have been borrowed by the laity from monasteries, as monks were the earliest settlers in many Alpine regions. Already in the 14th century, incense was a traditional feature of Nicholas plays and parades organized by the monasteries, and clerics were often called upon to cense non-ecclesiastic property in times of need. For example, in Bobingen, Bavaria, it’s recorded that a sacristan was recruited during the plague of 1635 to cense and bless homes after Christmas, New Year, and Epiphany services. In the 16th and 17th century, church incense was often sought by the laity, not only for such protective purposes but also for use in love-spells and other magic. After unsuccessful attempts to ban this sort of private use, the Church eventually conceded informally to such use when associated with particular feast days such as Epiphany.

The Rauhnächte are an ideal time for the fabrication of charms and the casting of spells. Magical herbs collected during this period are said to be particularly potent, and a broom made during these nights is able to sweep away evil spirits and disease. On Twelfth Night, water dipped from a spring or well at midnight possesses the power to heal, and divining rods cut on this night are infallible. Those blessed in the name of Caspar find gold, Melchior locates silver, and Balthasar yields water. The names of the Three Kings, written on slips of parchment and attached to the traveler’s leg, bless his journey and protect him from predators, robbers, and accidents. Water, salt, incense, and the chalk consecrated in a church on Epiphany have special power, and if windows are opened at midnight, the wind that passes through expels all evils. Midnight of the New Year offers similar potential. A glass from which all family members drink at this hour wards off ill fortune. Jumping from a table or chair at the stroke of midnight does likewise, and four stakes pounded into the earth at the cardinal points around a home safeguards the property from fire. Lentils, peas, and beans eaten on that night bring a fruitful year.

The “Knocking Nights” (Klöpfelnächte, Anglöckelnächte, or Glöckelnächte—all from the German for “knock”) were celebrated in Austria, southern Germany, and Switzerland, usually on the three Thursdays preceding Christmas. One of the earliest mentions of knocking customs comes from German scholar and writer Thomas Naogeorgus, who in the mid-1500s describes the practice in this poem translated from the Latin:

Three weeks before the day whereon was borne the Lord of Grace,

And on the Thursday boys and girls do run in every place,

And bounce and beat at every door, with blows and lusty smacks,

And cry, the Advent of the Lord not borne as yet perhaps.

And wishing to the neighbors all, that in the houses dwell,

A happy year, and every thing to spring and prosper well:

Here have they pears, and plums, and pence, each man gives willingly,

For these three nights are always thought, unfortunate to be;

Wherein they are afraid of sprites and cankered witches’ spite,

And dreadful devils black and grim, that then have chiefest might.

The Knocking Nights, like the Twelve Nights, were a time of ghosts and supernatural happenings, including the gift of speech endowed upon animals on these nights. The name comes from the custom of knocking on the walls of barns where livestock slept, thereby provoking the beasts to vocalize. In those sounds, one might discern the names of anyone in the village who would die within the coming year. Assuming Tyrolean kids of the 16th century were not so different from those today, it’s easy to imagine this custom propagating as groups of young people ran from barn to barn in search of spooky thrills.

At some point the emphasis of the practice shifted, and the nocturnally roaming youths themselves came to represent wandering ghosts, and their mischievous knocking would resemble the “poltern” (“noisemaking”) of the poltergeist. Some accounts make this clear, mentioning visiting youths knocking on doors and windows, and then quickly hiding themselves so that invisible spirits would be blamed. The prankish “ghosts” justified the game as one that brought otherworldly good luck to the homes visited. Eventually the practice was formalized to also include the performance of lucky songs or recited rhymes offered in exchange for treats. Some groups carried pronged poles used to rap on windows, with the prong used to extract the reward, usually a bit of cake, doughnut, sausages, or cheese impaled by the homeowner on the barb. Knocks with padded hammers and broomsticks, or even handfuls of dried peas thrown against windows, were all used in efforts to startle homeowners.

At times the aggressive nocturnal visits and noisemaking led to confrontations, and a 1616 account from Nuremberg, where the custom was known as “Bergnacht,” recounts that a girl was seriously injured by a tavern keeper who accused her of hammering on his establishment’s door with particular violence. By the 17th century, after unsuccessful bans, the Church pushed to reform the tradition as a religious one. The house-to-house visits were now said to imitate the journey of Mary and Joseph seeking lodgings on the way to Bethlehem, or participants were dressed as shepherds associated with the shepherds of the Nativity story. Songs that had previously reflected the rustic humor of the tradition’s pagan roots became Christmas carols. Possibly, at this point, the dates were shifted from the Rauhnächte to those before the Nativity to synchronize with Mary and Joseph’s travels.

Knocking Nights in Tyrol once included figures borrowed from the Nicholas parades or costumed witches and devils, who engaged in rowdy antics. In South Tyrol, Klöckeln groups still raise a ruckus with clanging cowbells and discordant trumpets made of goat horns. The masked troupe is accompanied by two particularly rowdy figures—the Zuslmandle who bickers and fights with his wife, Zuslweibl, played by a male in drag.

Disguised Berigln in Styria’s Ausseerland-Salzkammergut region go door to door during the “Knocking Nights.” Photo ©Salzkammergut Presseagentur.

In the Austrian state of Salzburg, and here and there in Styria and Upper Austria, the practice developed into something altogether different, the running of the Glöcklern, again from a Middle High German word for “knock.” Here knocking itself became strictly incidental, as the event is much better known for the lighted “caps” worn by participants. These are actually colorful paper lanterns braced on performers’ shoulders to support their large girth (sometimes measuring up to nine feet in diameter). Lanterns are decorated with intricate stained glass patterns created from colored tissue paper and punched cardboard covering light frames in the shapes of pyramids, crowns, crescents, suns, or stars. (During the Third Reich, there was an unfortunate one-off custom job sent to Berlin designed in the red, brown, and black color scheme of Nazi uniforms and decorated with swastikas.)

The lanterns did not become part of this Knocking Night tradition until the mid-1800s, competing with the region’s traditional masked performers until winning out around 1900. Though the careful craftsmanship of the lanterns may suggest more elevated intent, the new Glöcklern—as with other masked processions described in this book—at times encountered bans and confrontations with civil authorities. It’s said the all-white clothing the lantern-carriers wear was initially intended to help them disappear into snowy landscapes should trouble arise.

Glöckler from Ebensee, Upper Austria, first half 20th century. Photo: Volkskundemuseum, Vienna.

Now only remotely resembling other Knocking Night customs, the Glöcklern make their appearance exclusively on Twelfth Night. Given the date and their proximity to the Perchten tradition so strong in the state of Salzburg, their annual run is understood to represent the passage of benevolent Schönperchten. The bells they wear, like the patterns they follow in their run (circles, loops and figure eights—all signs for infinity), are said to repel evil and sustain and strengthen vital forces slumbering beneath the snow.

Pelzmärtel, the St. Martin Monster

The Rauhnächte or Twelve Nights could not contain all the sinister folkloric beings and malevolent spirits that roamed the Austrian and German winters. Appearing already in the first week of December, the Krampus himself demonstrates this. But even before this devil could swing his first switch or rattle his first chain, November had already seen the entrance of similar spooks.

Appearing on the eve of St. Martin’s Day (November 11), the “Pelzmärtel” (also “Belzmärtel,” “Belzmärde,” “Bulzermärtl,” etc.) combined the gift-giving function of St. Nicholas with the frightening antics of the Krampus. Wearing furs or ragged clothes, he roamed the villages of western Bavaria (Swabia and Franconia) scattering treats as bait for children, whom he would playfully strike with switches as they dove to retrieve them. The name is a compound of “Martin” (its diminutive “Märtel”) and “Pelz,” from “pelzen” meaning “to beat.” (Some etymologies relate it less reliably to the word “Pelz” for “pelts,” as in the fur costuming.) While this practice largely died out in the 19th and 20th century, in the Bavarian town of Wassertrüdingen, it persisted up through World War II, and since 1972 has been taken up again as an annual tradition. Like the Krampus, the Wassertrüdingen characters rove about in groups, wearing bells and brandishing switches. Their costumes replicate those worn before the war, namely, long fur coats and caps, along with waist-length false beards half covering their blackened faces. The treats they toss to children have traditionally been nuts, hence the regional variation on the name: Nußmärtel, or “Nut Martin.”

The similarity of all this to the Nicholas-Krampus customs is not coincidental. Along with the Nicholas play traditions, and those of the Perchten, St. Martin’s Day customs represent another likely influence on the development of the Krampus. Of particular interest is the matter of the switches and why the Pelzmärtel applies them. Though the Nußmärtel in Wassertrüdingen follows somewhat closer to the Nicholas tradition in pairing moral admonishments with the playful blows, this may be a modern accommodation as the traditional Pelzmärtel beatings are not described this way. In most cases, his beatings were disbursed quite without regard to good or bad behavior. They were just administered as part of the seasonal sport and as “good luck.”

Especially in their luck-transferring function, the switches wielded by the Pelzmärtel are generally understood to be identical to the Martinsgerte (“Martin’s switches”) presented on this day by cowherds or other herdsmen to their employers. As St. Martin’s Day was the traditional day in Austria and Bavaria to bring livestock in from the fields for the winter, it was on this day herdsmen collected their earnings from those whose animals they tended. As a token of gratitude for the payment and good luck talisman, they presented their employer’s family with the Martinsgerte. The bundled branches were said to bring good fortune if left hanging through the winter. In Bavaria, the Gerte protected the cow-stalls and stables, and in Lower Austria, it was hung indoors to bless the home. Usually cut from oak, birch, and juniper, the number of twigs and juniper berries were said to predict the number of cattle or loads of hay the farmer might expect in the following year. In some cases, the switches were presented to children. In the spring, the switches would be used to drive the livestock back out to pasture, instilling health and fertility in the animals as each was struck upon departure.

Wolfauslassen in Rinchnach, Bavaria. Photo by Dengler Günther ©Tourismusverband Ostbayern e.V.

Processions of herdsmen returning on St. Martin’s Day from the fields in some areas of Austria and Germany evolved into particularly festive rituals. To provide a bit more fanfare for their seasonal march, the bells no longer required by the animals were worn by members of their procession. The clamor raised could simply celebrate completion of a season’s work but might also serve as intimidating warning to any employer not ready and fair with his pay. Because a primary duty of the herdsman was to protect his animals from predators, and because it was the wolf feared above all, this procession with its noisy bells came to be called the Wolfauslassen or Wolfablassen, meaning “letting out the wolves,” or, occasionally, the Wolfausläuten (“ringing out the wolves”). Whatever the name, the meaning was the same: wolves may now leave their forest hiding places and traverse the pasturelands.

The Wolfauslassen tradition began sometime in the 18th century, and was particularly associated with the easternmost Bavarian Forest. Its evolution is sometimes described as beginning with shepherds themselves wearing the bells, but as the tradition gathered momentum, tagalong village youths were recruited, either to wear the bells, or—it’s sometimes said—to dress and act the role of wild wolves. Even today where the tradition lives on but is no longer enacted by actual shepherds seeking payments, groups of bell-wearing men called the “Wolf” still follow an appointed “Shepherd” door to door begging for food, drink, or money (now usually for charity). The Shepherd carries as a staff a version of the Martinsgerte, in this case, a large branch stripped of smaller branches at the bottom, gathered at the top into a sort of bush.

Since the years following World War II, the Wolfauslassen has experienced a rebirth, particularly in the Bavarian towns of Rinchnach and Bodenmais, where the event has become popular with tourists. In the process, Wolfauslassen groups competing for attention have abandoned the normal cowbells once used and adopted enormous custom bells, sometimes measuring nearly 3 feet wide and weighing as much as 80 pounds. It’s no longer youths carrying these massive bells but hearty adult males, who each wear a single bell strapped to the waist and positioned like an enormous fig leaf. Stopping in front of each house visited, the Wolves form a tight, inward-facing circle, and ring their bells in a frenzy of hyper-masculine pelvic thrusting, a movement delicately described by local historian Jose Dengler as having “a certain aura.”

The peculiar Wolfauslassen ritual did not develop in all areas. In most, the young tagalong participants came to play a more prominent role than herdsmen in the door-to-door processions. Especially further north in Germany, participating youths began carrying candles in hollowed turnips or pumpkins, and this practice, in turn, gave way to parades of paper lanterns and St. Martin bonfires still seen today. As with the Pelzmärtel customs, St. Martin’s Day became a rather child-centered holiday (similar to St. Nicholas Day).

This emphasis on children and the domestic sphere may have had something to do with the season’s agricultural labors coming to a close. For centuries, this day was regarded as the traditional beginning of winter. St. Martin’s Day marked the beginning of the indoor life, one lit by those lanterns and fires that came to symbolize the holiday. It was a day for settling business and settling in. Leases and other annual contracts ended on November 11. It was a day of slaughter and preparation of the St. Martin’s Day goose, and St. Martin’s Day beef. The first wine of the year was also drunk on this day, and it was generally a time set aside to enjoy the fruits of one’s labors, domestic warmth, and conviviality.

Feasting on St. Martin’s Day also made sense as it once marked the last day before the Church’s 40-day Advent fast anticipating Christmas (formerly called the “St. Martin’s Lent”). But the feasting customs associated with this date are clearly older than the Church’s 5th-century creation of Advent. The custom of slaughtering (and feasting on) livestock at a time when seasonal changes no longer allowed grazing would be as old as any form of animal husbandry in that climate. In the case of the ancient Germanic peoples, it’s assumed that at some point between mid-October and mid-November, near the date later settled upon by the Church as St. Martin’s, this slaughter and feast occurred. It marked not only the start of winter, but for the Germans (like the Gaelic Celts), the New Year. Most historians agree that the significant body of customs accumulated around the feast of St. Martin in German-speaking lands point to an important pre-existing Germanic New Year celebration rather than any native fascination with the Church’s otherwise relatively inconspicuous saint.

Halloween Leans toward Christmas

As St. Martin’s Day jack-o-lanterns and the Celtic New Year we call Halloween have been mentioned, it’s time to address something many readers might’ve been wondering since I first mentioned costumed Austrian youth begging for treats on nights the dead wander the earth, namely: Aren’t all these winter-spook customs just a version of Halloween? Similarly, readers may have found themselves nagged by another: Why do St. Nicholas Day customs duplicate Christmas?

While bigger answers can certainly be found for these big questions, a shorter answer would simply be: “Hay.” More specifically, it was advances in the agricultural technology during the Carolingian era that allowed meadows to produce more fodder for the winter, thus allowing animals to be kept longer and butchered later. This caused the major winter feast (and a portion of its customs) originally celebrated on St. Martin’s (11/11), to be later moved to St. Andrew’s (11/30), then to St. Nicholas’ Day (12/6), and finally, St. Thomas’ Day (12/21) during the week of Christmas. Similarly, it’s possible that thanks to improvements in agricultural technology, Germanic year-end customs like those associated with the visiting dead were nudged forward from November later into the Rauhnächte. This would account not only for parallels between various Rauhnacht traditions and those of the Celtic Halloween, but also for Nicholas customs edging their way into Christmas, and a general blurring of customs of the late fall and early winter.

While all this is general and speculative, we have more definitive detail suggesting that old St. Martin’s Day customs were transferred to St. Nicholas Day. The Pelzmärtel and his switches, and the child-focused emphasis of St. Martin’s Day offer obvious parallels with St. Nicholas Day customs. Even the Krampus tradition, with its pairing of a pastoral bishop leading a wolfish pack of bell-ringing beasts, might be compared to the visiting shepherds and wolves of the Wolfauslassen. Some even project the matter further, seeing in the bundled branches of the Martinsgerte a precedent for the Christmas Tree.

The slide of St. Nicholas customs into Christmas can partly be explained in terms of Protestant efforts to preserve those customs apart from any association with the Catholic saint. However, the influence of the agricultural shift cannot be discounted. Not only would the traditional slaughter of swine only four days prior to Christmas on St. Thomas Day encourage lavish Christmas Day feasting and merriment, but a generalized cascade effect caused by moving the first day of winter from November to December would inevitably tend to push any number of interconnected traditions later into the month.

Even after Advent was shortened to eventually begin the fourth Sunday before Christmas (instead of St. Martin’s Day), Martin’s association with Christmas and winter remained fixed in the German mind. As personified by the folksy Pelzmärtel, a figure with no pretense at representing an actual Catholic saint, Martin made a better Protestant gift-giver than the robed and mitered Nicholas. In Franconia, a Protestant-leaning region straddling Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg, the figure became associated with Christmas gift-giving. Horned and wearing a suit of pleated straw with bells woven to the chest, a peculiar version of the Pelzmärtel appears on Christmas Eve and Day in the town of Bad Herrenalb and around the Gais Valley. Imported by Tyrolean immigrants in the 17th or 18th century, this figure accompanies a Christkind (a costumed angel representing the newborn Christ), who offers small gifts to children in exchange for pious recitations. This Pelzmärtel’s straw suit, which takes roughly 100 hours to create, has been woven by the same family for decades, and the identity of its wearer is a “secret of the Gais Valley.”

Wild Barbaras

Around nightfall on St. Barbara’s Day (December 4) in the town of Sonthofen, and a few other communities in the Upper Allgäu region of the Bavarian Alps, there appear groups of strange figures known as Bärbele (“Barbaras”), or sometimes “Wild Barbaras.”

Dressed in old-fashioned peasant skirts, aprons, and kerchiefs, they each carry switches and wear a cowbell or two belted to the waist. Their most distinctive trait, however, are their masks, each handcrafted and covered in weird mosaics of lichen, moss, bits of acorns, pine cone, or other forest materials. Behind the masks are young women, who are ideally over the age of 16 and still unmarried—traditional parameters for participation as they approximate the virgin martyr Barbara at the time of her death.

In Sonthofen, roughly 80 Barbaras annually sweep through the town’s central pedestrian areas, administering light blows to those approaching too close and awarding apples, cookies, or nuts to well behaved children and their mothers. In a reversal of the macho Krampus tradition, the all-female Bärbele tend to target young men with sharper and more frequent blows to the lower leg, though these, like the blows of the Pelzmärtel, are not punitive and generally said to convey good luck or vitality. Blows often may continue until the victim begins to hop or dance to the satisfaction of the attacking Bärbele. In some other areas, the Barbaras may visit homes, using brooms to symbolically sweep evil from the home, into the yard, and out to the street. It is said that the more troubling evil spirits that can’t be removed by the Bärbele must wait two days to be exorcised by the visits of St. Nicholas and his accompanying devils, regionally named Klausen.

The Barbara run or Bärbeletreiben (“Barbara drive” or “bustle”) is of indeterminate origin, but is understood to be very old. The practice had lapsed and nearly fallen into obscurity when efforts to resurrect it began in the late 1970s. Since 1985, the event occurs annually in a growing number of communities. The area’s special relationship to St. Barbara is further indicated by the fact that her day, rather than St. Nicholas Day, was formerly the local day for children to receive gifts.

The Allgäu Bärbeletreiben is not to be confused with the Bärbelilaufen of Upper Franconia, in which boys dressed in ragged disguises went out after dark with switches, striking any young woman who dared to show her face, calling her shameful names. The actions of the boys, called “Torture Fathers” (Folterväter), are said to allude to the martyrdom of the saint. Unsurprisingly, this less than charming custom has not survived into the 21st century.

A final bit of fortunetelling attached to St. Barbara’s Day reminiscent of the Rauhnacht customs is that of Barbarazweige (“Barbara branches”). These are cut from a blooming tree brought inside on this day and placed in water. A flowering fruit tree, like cherry, plum, or apple, is traditional, but birch, hazel, or others may be used. Once indoors, the warmth causes buds or blooms to appear. These are regarded as bringing luck for the coming year. Their number can indicate the size of the year’s crop; branches can be assigned by female hopefuls to various suitors to indicate a future groom, and systems have even been contrived whereby the buds might predict lottery numbers. References to Barbarazweige appear as early as the 13th century, and the tradition is supposed to be based on an incident during which the saint’s robe caught on a branch as she was being dragged off to prison. She is said to have preserved the broken branch in her cell, standing it in a cup of water where it thrived, and at the hour of her execution, bloomed.