Percht from Barmstoana Perchten, Hallein, Austria. Photo ©Roland Käfer.

While benevolent Schönperchten may be the focus of Gastein’s celebration, the appearance of these figures in the parade dates only to the middle of the 19th century. Even though early folklore may have sometime associated Perchten with good fortune, the name and probably concept of Schönperchten first appears contemporaneously with the emergence of 19th-century Tafelperchten, so we are hardly encountering pre-Christian mysteries here.

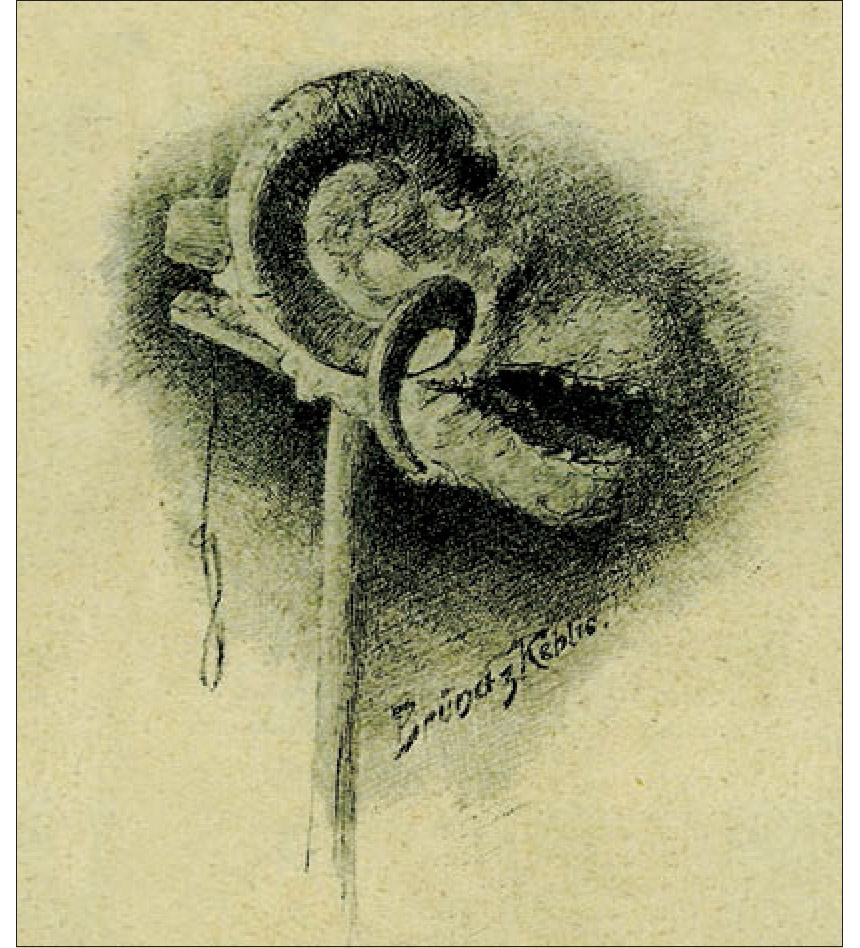

“Das Perchtenlaufen im Salzburgischen” by Oskar Gräf for Die Gartenlaube (1892).

If we return to the figure first mentioned in this chapter, the Habergeiß, we gain a better foothold in the Perchten’s mythology. Though the word Perchten tends to refer rather loosely to an undifferentiated group of Alpine winter demons, this Percht offers a uniquely well-defined body of folklore.

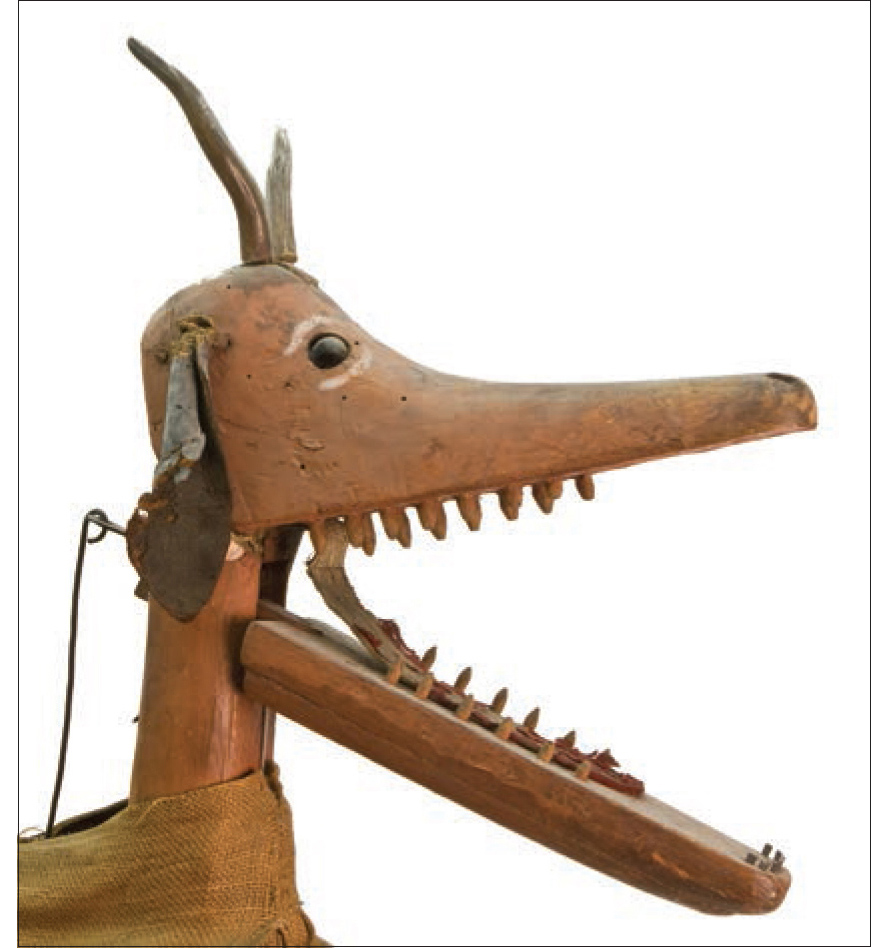

The two-legged Gastein embodiment of the creature is only one of many ways the Habergeiß is represented. He often appears as an immense four-legged beast impersonated by two performers hidden under hides or blankets. Sometimes there are four men, with the foremost operating the head (carved from wood or crafted out of other materials, sometimes even an animal skull). Occasionally it’s just one man hunching forward, clutching wooden canes, sticks, or brooms to simulate legs. Sometimes the long neck is even done away with, and the performer wears an outfit similar to the Krampus but with a mask carved to look like a goat.

Along with appearing as a Percht in Perchten events, the creature is associated with the Wild Hunt, and would show up in Nicholas plays or processions. Less frequently it’s a figure in Carnival parades, and in earlier times, it would even make appearances at weddings to convey a blessing upon the couple.

As with any creature of the imagination, the Habergeiß, before it came to be embodied as a costumed figure, was of more ambiguous form. Though most often described as a sort of goat, it sometimes possessed only three legs, two hind and one foreleg, or it might be imagined as a goat with ponderous horse hooves, or a goat with wings. This birdlike nature is often mentioned. Sometimes it’s a great and loathsome bird with three legs. Or is half-bird, half-goat. In Tyrol it could be a bird that somehow looked like a man. In Styria and Carinthia, it could even be a winged dragon, or the embodiment of the Devil, or the Dark One’s mount. Sometimes it was said to visit sleeping victims at night and press its weight upon them like the Drude, causing what we now call sleep paralysis.

Habergeiß mask from a NIcholas play. Pustertal, South Tyrol. ca 1900. Photo: Christa Knott ©Volkskundemuseum, Vienna.

In Styria, one legend identified the Habergeiß as the ghost of goat that plunged from a cliff with its master during a flight from a creditor eager to seize the animal. Other stories describe it as a departed soul in the shape of a goat haunting the fields around a home in which someone lies dying.

While it was not easily seen, it was often heard. Its voice was sometimes like the bleating of a goat, at others, the cackling of a goblin, the shriek of an owl, or the croaking of a toad. Woe to any who would dare to imitate its hideous call; the Habergeiß would come by night and attack him. The cry of the Habergeiß usually heralded misfortune, particularly if it followed the ringing of the Ave Maria. Should its call precede the bells, however, good fortune might follow. Hearing its call in the autumn foretold a long and grueling winter, though sometimes its call, like the cuckoo’s, could announce the coming of spring.

The Habergeiß particularly bedeviled farmers. Its appearance caused cows to go dry or grow thin and turned milk sour. It was particularly destructive to crops. It would come amidst hailstorms that battered the plants, trample or cut the grain, or scatter ordered piles of cut grain into neighbors’ fields. Sometimes it appeared in the company of, or was ridden by, the Pilwiz, an evil spirit that walked or rode through fields with sickles at its feet, leaving swathes of destruction.

The Habergeiß has often been said to essentially represent a spirit of the fields, one identified with grain. The word Haber, after all, is an Austrian word for “oats” and “Geiß” a dialect word for “female goat.” However, this etymology has been widely disputed by those deriving “Haber” instead from the Proto-Germanic “Hafr” used for male goats, making the creature a sort of male-female enigma. Others have suggested that “Geiß” is in fact a corruption of “Geist” (spirit).

Habergeiß from German-settled German Bohemia. Drawing by Karel Rozum for Den se krátí, noc se dlouží (“The Day is Short, the Night Lengthens”), 1910.

Habergeiß, Buchbach, Lower Austria (ca. 1900). Photo ©Volkskundemuseum, Vienna.

Habergeiß at Nicholas play in Tauplitz, Austria. Photo ©Wolfgang Böhm.

Whatever the source of this mysterious name, there is an association between the name and folk customs associated with grain harvest. In a 1905 volume on “forest and field cults” by Wilhelm Mannhardt and Walter Heuschkel, many of these are detailed. In Straubing in Lower Bavaria, the last grain to be cut was called “the Korngeiß, Weizengeiß, or Habergeiß.” (corn-, wheat-, or oat-goat), and on the gathered sheaves, two horns were placed. In Upper Austria, “Habergeiß” could be a name for the last bit of stubble cut. In Swabian Germany, reapers created from wood and oat sheaves the figure of a goat, which was decorated with flowers and set out to honor the field, and they called this a Habergeiß. Or it could be a straw goat left as a taunt to the neighbor slow to finish his harvest, or as mockery for any competition lost.

The often-questionable tendency to interpret folk practice in terms of ancient and forgotten fertility rites was in vogue at the time of the above-mentioned volume’s publication. Many peasant customs were assumed to be of much older provenance than researchers believe today. Near Bad Griesbach in Bavaria, there is even a boulder that is said to bear a carving of a Habergeiß dating to the Stone Age. The carving, whatever it truly represents, can be viewed in a small cave formed by two curiously placed boulders leaning together. The area is long assumed to be haunted, and the boulders are said to have been deposited there by the Devil, who was startled by church bells while on his way to drop the stones on the nearby Tettenweis monastery. The carving is believed to depict a meter-high Habergeiß (also simply identified as the Devil). It appears to be dancing with small horses and other characters. The style of the carving, and stone-age artifacts recovered around the site, have suggested to locals a prehistoric origin.

The cave and its reputation have even served as inspiration for a contemporary Perchten group in nearby Rottal, the Brauchtumsverein Rottaler Habergoaß, Hexn und Rauwuggl, whose members costume themselves as the Habergeiß as well as witches and Rauwuggl, an obscure monster resembling a Krampus without horns. Beginning in the 1700s, the cave also served as the headquarters or “church” of a secret society known as the Haberfeld movement. The Haberfelder were a masked vigilante group expressing community outrage at certain transgressions (especially adultery and extramarital pregnancies) through intimidating nocturnal visits to the homes of those accused. Similar to the charivari in France, the Haberfelder used guns, firecrackers, whips, drums, horns, and other noisemakers to frighten the victim and possibly force them from hiding to offer a confession. The society’s name comes from the word for “field” (Feld), and “Haber,” which can be taken here to mean “fellow” or, some say, “goat,” as goat skins were often part of the Haberfelder’s disguise, along with masks, dark clothes, and blackened faces.

We’ve defined the Perchten as winter spirits of the Austrian and Bavarian Alps somehow associated with Frau Perchta or with the eve of Epiphany, “the shining night,” “giberahta naht.” Along with the manlike Percht known in Gastein as the Kramperl, the goat-like Habergeiß is the only well-articulated representative of the genus.

What is surprising about the creature is the number of similar figures that appear in Christmas and New Year’s traditions far removed from the Perchten’s home. In the introduction to this book, I’ve already mentioned the Welsh Mari Lywd represented during the Twelve Nights as a horse skull paraded on a pole by draped performers. While this might be dismissed as chance resemblance, there are other geographically closer instances where a direct borrowing or common lineage seems more possible.

Though once more widespread, the Swiss Schnabelgeiß (“beak-goat”) still can be found around Christmas in the area around Zürich. Like the Habergeiß, this creature is represented by a draped performer holding a goat-head with a hinged jaw. It was one of the Spräggelen, frightening spirits who visited homes to ensure good behavior among children and young women working as spinners. In the Italian South Tyrolean town of Termeno, the Egetmann Carnival parade features similarly contrived but particularly large creatures known as Schnappvieh (“snapbeasts”) or Wuddelen.

Oddly enough, most of these Habergeiß lookalikes are found far to the North, nearer the North Sea and especially the Baltic coastal regions that were once part of the German Empire. In old Pomerania, now divided between northeast Germany and Poland, the Klapperbock (“snapping buck”) also consisted of a hidden performer and snapping head on a stick. It would appear at Christmas to frighten children who had neglected prayers and other duties, and was usually accompanied by someone costumed in straw as a “bear,” and another costumed as a stork, though exactly how a stork costume was realized is not clear.

A fourth traditional companion in this troupe might be the Schimmel (a gray, white, or ghostly horse). While the figure might be represented by a crouched, draped performer with puppet head, the phantom horse might also appear as a hobby-horse ridden by a ghost rider, the Schimmelreiter. The folklore of the Schimmelreiter is also found west of Pomerania in the northern lowlands of the German state of Schleswig-Holstein. The Schimmelreiter is probably best known to most Germans through Theodor Storm’s 1888 novella of that name, in which tales of the phantom rider frame hard-edged depictions of life on the windswept heaths and shorelines of Northern Frisia.

In the Prussian Empire’s more Polish regions, where the goat was often known as the Turoń, similar animal mumming customs thrived. In Silesia a larger version of the Schimmelreiter might consist of three or even four youths hidden under draped sheets, and a rider, who might also be veiled. Sometimes the rider would wear atop his head a pot filled with burning coals cut like a jack-o-lantern with glowing eyes and mouth. In Lithuanian East Prussia, the Schimmel’s head was sometimes a horse skull with lights installed in the eye sockets. Here too, the horse was accompanied by traditional straw bear, stork, and a goat with snapping jaw.

Across the Baltic Sea in Finland, there is the Joulupukki or “Yule buck,” also once represented by a draped performer holding or wearing what looked like a goat head. This sometimes frightening gift-bringer over the years became strangely intermingled and finally more or less replaced by a figure mostly identical with the more benevolent American Santa Claus. A sort of fanciful hybrid of the monstrous character and the modern St. Nick was amusingly depicted in the 2010 Finnish movie Rare Exports. A similar figure, Nuuttipukki, also once visited homes in Sweden and Finland on January 13, St. Knut’s Day. From the 11th century, we also have reports of Holy Innocents’ Day celebrations involving a man costumed as a goat led by St. Nicholas. Related mumming customs continued throughout the 19th century and into the early years of the 20th. Sometimes the Krampus is compared to these figures.

There is also a Scandinavian harvest tradition similar to that mentioned above. The last sheaf of grain was sometimes described as a goat or as a “Yule buck” (Julbock) and kept through Christmas as a magical token. As a seasonal prank, straw or wooden effigies of a goat were likewise secretly hidden on neighbors’ property with tradition demanding the object be returned in like manner.

My reasons for so thoroughly enumerating these figures is that their geographic dispersion might be taken to indicate historical diffusion of the Habergeiß figure, and by extension, the whole Perchten mythology.

Having preserved pagan beliefs and practice long after Christianity had been assimilated into the rest of Europe, Scandinavian tradition has always represented an enticing model of pre-Christian Germanic custom in regions to the south. If we are searching for ancient and unadulterated pagan elements within the Perchten folklore, this connection between the Alpine Habergeiß and Nordic traditions seems particularly interesting. The presence of the Klapperbock and similar figures near the Baltic and North Sea coasts of the old German empire hints at a southward diffusion from Scandinavia, one which parallels that first wave of migration that brought Germanic peoples south into the region between Germany’s Oder and Elbe rivers around 1000 BC.

However, there are immense gaps—both chronological and geographic—between the appearance of the Habergeiß and its fellow Perchten in the Alps during the Christian era and what little is known of the beliefs and practices of pre-Christian Germanic tribes. While there are similarities between the folklore of the Alpine regions and Germanic beliefs further north (e.g., those between Perchta and Holda), there is a geographic missing link when it comes to the Habergeiß. Figures resembling the Habergeiß are difficult or impossible to find in those central regions between the Alps and the remote northernmost edge of the old German Empire.

Ultimately, the possible diffusion of folkloric influences from Nordic sources requires an examination of tribal migrations supported by archeological and linguistic evidence far beyond the scope of this book. While this topic would seem fruitful for investigation, any theories connecting southern German traditions with Nordic beliefs are now subject to particularly skeptical scrutiny thanks to the wildly speculative scholarship of Third Reich scholars bent on discovering “pure” Nordic roots for any and all folkways present in German-speaking lands.

Roman influence or Romanized Celtic influence on the Perchten can also not be ruled out when considering figures, which—like the Habergeiß—appear in far-flung locations once under Roman control. In Chapter Two, we have already encountered a possible common thread in the similarly widespread processions of men costumed as “horned beasts” during the Roman January Kalends.

Traditions of the Late Roman Empire tended to be particularly well-preserved by the Eastern Church and its associated folk culture. Not surprisingly, traditions of New Year’s and Christmas animal masking (similar to that of the Roman Kalends) is quite prevalent in lands dominated by or experiencing significant contact with the Orthodox Church. The word “Kalends” itself is preserved in the names for these customs in these regions, i.e., “koliada” in Russian and Ukrainian, “kolęda” in Polish, and “koleda” in Czech, Slovak, and Croatian. In most of these traditions, figures similar to the Habergeiß have been or are represented.

The function of the Habergeiß in Alpine culture is to enforce the social order. A visit from a costumed Habergeiß blessed those who perpetuated that order through marriage, and at the same time represented, according to Mannhardt and Heuschkel, “a hand of justice by pursuing, for example, sinners,” and frightening the disobedient including “children who torture animals and lazy maids.” It attacked troublemakers who dare to wander into the grain fields or forests where they do not belong. This association with reward and punishment is most prevalent in the many instances of the Habergeiß appearing alongside Nicholas.

The authors even cite a practice from Bavaria’s Bohemian Forest in which the Habergeiß is made to explicitly play a role like that of the dark St. Lucy, describing a creature represented “as a goat with a spread-over sheet and horns poking through but with the name ‘Luzia’ as it personifies that saint’s day.” Like Perchta, the figure “exhorts the children to pray, bestows upon them tasty fruit, and threatens the wicked with the prospect of having their bellies slit and stuffed with straw and pebbles.”

Magic Rite or Playful Celebration?

Though we often discuss folkloric entities in terms of peasant superstition, as beings greatly feared and respected by rural populations, it should be recognized that more often than not, when the Perchten appeared as costumed figures, it was understood as a distracting entertainment for adults or edifying game for children. The same must be said of the Krampus. Too much can easily be made of a possible magic function in driving off evil, awakening the spring, or blessing field. Though magical thinking might have been more at home in remote Alpine villages of the 18th and 19th century than our world today, looking for magical intent every time a farmer dons a pair of goat horns can be as ridiculous as regarding the appearance of a costumed Uncle Sam parading on July 4th as a ritual to ensure American military victory.

One of the earliest records of a procession in which the Holda-Perchta folklore is represented describes something closer to a civic festivity than magical ritual. Though it is Eckhart rather than Holda herself mentioned, it seems to be the same horde of wandering souls referenced. In 1688, Lutheran minister P.C. Hilscher describes the custom then extant in Frankfurt:

Every year a number of youths were paid to take a large cart covered with leaves from door to door, to the accompaniment of songs and predictions which, to prevent errors, they had been taught by experienced people. The populace asserts that in this way the memory of Eckhart’s army is celebrated.

Witchcraft scholar Carlo Ginzburg, in his Ecstasies: Deciphering the Witches’ Sabbath, points out that in this case, the performers were paid actors rather than earnest petitioners of the spirits. While perhaps the more superstitious might believe that secrets of the future could be discovered within Holda’s Venusberg, here the prognostications would have been mostly offered in the spirit of fun, or as a commemoration of a time when such things were widely believed (before the relatively early date of 1688, it should be noted). If anything, the description seems to hint at something a bit cynical, with “experienced people” teaching the youths how to “prevent errors” in their fortunetelling, perhaps by keeping pronouncements extremely general, ambiguous, and hard to verify.

Aside from the handful of events in Austria’s Pongau region (where Gastein is located), the oldest Perchten events date only to the years after World War II. The Wild Hunt of Untersberg, held annually in the shadow of the Untersberg Mountain on the southern outskirts of metropolitan Salzburg, is one of these. While the Perchten are most strongly associated the Rauhnächte, the Untersberg event brings them out earlier in December, on the second Thursday of Advent. Likely the date is borrowed from local “knocking” customs (Anklöpfeln) occurring on Thursdays in Advent. Though it was only organized in current form in 1949, thanks to its incorporation of older elements of local customs like Anklöpfeln, it’s sometimes said to have roots in the 1880s. The event is rather meticulously anchored in regional folklore, particularly tales of phantoms said to pass over the swamplands of the now-dried Leopoldskron Moor or spirits associated with the Untersberg Mountain.

Accompanied by torchbearers, the maskers, all hung with jangling bells, march to the beat of a drummer costumed as Death. The troupe is limited to twelve performers, a number often traditional for Perchten, and also includes the Moss-wife often mentioned as prey pursued by the Wild Hunter, a Baumpercht (a tree spirit covered in bark and fir branches), a costumed bear and his wrangler, a witch, the boar Saurüssel, the two-man, four-legged Habergeiß, the rooster Hahnengickerl symbolizing vigilance and fertility, the benevolent giant of Salzburg lore Abfaltersbach, and the Raven, a bird said to eternally circle the Untersberg mountain and tasked with awakening on the last day the king and his armies slumbering within (usually Charlemagne, but sometimes Frederick I or Charles V).

As each house is reached, the Perchten begin a circle dance accompanied by fife and drum. The monsters bob, crouch, twirl, and change direction. Every third step is a hop and clatter of cowbells. At the sound of Death’s drumroll, all freeze in their circle. All bells fall silent. With the next drumbeat, the ring bursts, and the dancers charge the crowd. At the crow of the Hahnengickerl, the melee stops, and all Perchten drop to their knees. The witch steps to the center. With her broom she sweeps out a large cross upon the ground. The Chief Percht then declares:

“Glück hinein, Unglück hinaus,

es ziagt des wilde Gjoad ums Haus”

(“Fortune in, misfortune out,

The Wild Hunt goes round your house.”)

Again the Hahnengickerl crows. The dancers, accompanied by fife and drum, again perform the Perchtentanz. As the song concludes, the Raven crows, and all figures kneel one last time, prostrating themselves as if to transfer energies accumulated in their dance into the earth. This concludes the visit, and they depart.

The Bavarian town of Kirchseeon, about 30 minutes east of Munich, also hosts a well-known Perchtenlauf created in the winter of 1953-4 under the direction of Dr. Heinrich Kastner, a cultural preservationist who also headed the town’s local Trachtenverein (a club devoted to traditionalist culture and folkloric costume specific to the region).

The event reflects a meticulous, if idiosyncratic, attention to detail in its costumes and choreography, all intended to reinforce an interpretation of the folklore internally consistent if slightly out of step with recent scholarship. The Perchtenlauf is visually rich with roughly two-dozen Perchten featuring unique, richly ornamented masks, and colorful costumes. It incorporates traditional songs, complex dances, and music on a variety of instruments including a wheeled Glockenspiel with tuned bells arranged on a decorative tree-like structure.

Death as drummer at The Wild Hunt of Untersberg, Salzburg. Photo ©Jung Alpenland.

At dusk on Saturdays and Sundays, between the last weekend of November and Epiphany, performers gather at a different spot each day. Their torchlight procession begins with three crashing, jangling thumps produced by a strange instrument held by the Chief Percht, his Teufelsgeige (“devil’s violin”), a staff cluttered with cymbals, bells, and topped by a grotesque, carved head. As the assembly moves out, masked drummers set a beat and others crack whips.

The drummers and musicians manning the Glockenspiel are Kirchseeon’s version of the Schönperchten, one of the five classes of Perchten here called “Passen.” Their masks represent human faces crowned by decorative helmets adorned with magical talismans, mirrors, musical symbols, heraldic devices, and shellfish representing fertility. The figures go by strange names including Harp, Bard, Hexagram, and Pentagram, Indian, and Firebird.

Frau Perchta assumes a central position in the Perchtentanz performed by Kirchseeon’s Schiachperchten. These consist of two Passen with the names Klaubauf and Holzmandln (“Wood Folk”). Perchta carries a staff topped by a pentagram and wears a peculiar mask with a male devil facing forward and a backward female visage set in a burst of sunbeams.

Interestingly, the design of the feminine face is believed to have been influenced by a mask created for the 1934 film, The Prodigal Son, by South Tyrolean director Luis Trenker. In the film, the protagonist encounters folk rituals featuring the Perchten along with an interestingly staged scene emphasizing a relationship between the awakening of natural forces and the Perchten (who appear rising from under the winter snows). The film’s Sonnenpercht (“sun Percht”) mask with its sunbeam halo, a design unprecedented in actual folk traditions, reflects the mythology embraced in the Kirchseeon festivities, identifying Perchta as an all-powerful goddess of “an old sun cult.” Her peculiar male visage is explained by her dominion over all dualities, “male and female, life and death, past and future.”

A number of dances are performed over the course of the Perchtenlauf, usually accompanied by drums, Glockenspiel and traditional lyrics chanted or sung. There are round dances executed in patterns—circle, square, and star formations—said to have magical significance. Most striking is the Drudenhax (“Pentagram”), a dance in which the Wood Folk circle, chant, and form complex patterns with the long hazelwood staffs they carry. At the close, they interlock these, forming the shape of the pentagram, which is raised skyward.

The names and masks of these dancers are noteworthy. The Klaubauf faces are carved in a grotesque rounded style resembling those of East Tyrol, the region most associated with that name. They represent the malevolent Luz, Boar, Bat, Werewolf, Dragon, Devil, a froglike Wasserman (“Water Man”), an evil-looking Hare, and a raptor-like Bird. The masks of the Wood Folk incorporate forest elements: a pinecone for a nose, a fern branch for an ear, a snail shell for a wart, and a hat modeled on a mushroom cap. One named Snapdragon is modeled on the dried seedpod of that flower, which itself resembles a human skull. While some traditional animal fur is incorporated into the clothing, most of the Perchten instead wear coveralls decorated with layers of colorful yarn strands suggestive of fur.

At each stop along the route, these dances, songs, and chants are performed, and the visit concludes with the Habergeiß symbolically offering a rhymed blessing. He is then repaid with coins deposited into his hinged jaw and “swallowed” into a hidden bag. While the Kirchseeon Habergeiß is surprisingly atypical and utterly lacking in goat-like ears, horns, or other traits of the animal, there are figures closer to the traditional Habergeiß in the final Pass. These are the Schlenzer, consisting of the familiar draped performer holding a rod topped by a puppet head with flapping jaw. The Schlenzer are known for sneaking up on spectators otherwise absorbed in the performance. Their most notorious prank involves scooping up mouthfuls of snow and dropping them down the collars of the unwary.

Tresterer, Zell am See, Austria. Photo by Johannes Schwaninger ©Steinerwirt, Zell am See.

Krapfenshnapper from Tresterer group, Zell am See, Austria. Photo by Johannes Schwaninger ©Steinerwirt, Zell am See.

The Kirchseeon Perchtenlauf has received extensive coverage: local, national, and throughout the EU via print, TV, radio, and online media. Unlike the secretive modus operandi of organizers of the Wild Hunt of Untersberg, Kirchseeon event producers post routes, festival information, and advertising throughout the city, drawing spectators to line the streets hours in advance. Though eschewing appearances at “some of the more commercial Christmas Markets,” the desire to expand the audience is clear and seems fueled by a sense of righteous duty coloring Kirchseeon’s Perchten mythology—as in this quote by H. Reupold, Jr., son of the event’s founder:

“Perchten, in the broader sense, are those who, with their entire thought and actions, set an example in both private and public life. They are committed to social needs as much as the cultural. Finally, as the translation of Percht is ‘bright, shining,’ we must, as the saying goes, “be a shining example.”

A Perchten tradition with genuinely old roots is that of the Tresterer dancers found in the Pinzgau region of the state of Salzburg. The practice has been preserved in five municipalities (Bruck, Stuhlfelden, Unken, Zell am See, and the city of Salzburg) and takes place only during the twelve days of Christmas, except in Zell, where it also occurs on St. Thomas Day.

Classed as benevolent Schönperchten, the dancers’ elaborate costumes are unlike those worn by Perchten in any other region but may represent a style more typical in the past. Particularly striking is the crown surmounted by white rooster feathers and hung with several dozen colored ribbons dangling to the dancer’s hips. Partially obscuring the face, the ribbons are thought to have functioned perhaps as a disguise during the years when Perchten events were banned and carried out in secret.

The cut and rich brocade of the clothing recalls costume of the 18th century and is restricted to a symbolic color scheme: red for defensive power and white for purity. An embroidered belt and handmade shoes with hobnailed wooden soles complete the outfit. In the right hand, the dancers also carry and occasionally wave a handkerchief, as do the Morris Dancers of England. The dance is executed in a combination of light jumps, grinding spins, and heavy stomps, commonly said to awaken the earth’s dormant energies. It is intermittently accompanied by music performed by pipers, dressed in folkloric costume.

The Tresterer, like other traditional Perchten, roam from home to home giving their performances and are accompanied by other figures including Schiachperchten and a Habergeiß. The master of the procession, whose duty it is to offer rhymed blessings to the host and symbolically sweep open the spot where the Tresterer will perform, is a figure called Hanswurst, the name for a traditional Carnival fool throughout German-speaking lands. Here he wears a tall feathered, berib-boned hat and white suit adorned with jingling bells. He carries a leather club or “sausage” (Wurst) used to clear the performance space and to threaten any misbehaving Schiachperchten.

Also accompanying the troupe are the bufoonish husband and wife Lapp and Lappin, both played by men. Carrying a rag-doll “baby,” Lappin is a figure of low comedy, one constantly and indiscriminately pregnant. Her antic attempts to hand off the doll to spectators are said to convey to them the gift of fertility (whether desired or not!) A Zapfenmandl (“pinecone man”) and the lichen-covered Werchmandl also appear with the Tresterer. Their presence is intended to bestow symbolic protection upon woodcutters and forest workers, and guard their trees from fire, wind, disease, and infestations.

Finally come two Perchten in animal form. The Hühnerpercht (chicken Percht) is outfitted in feathers and mask more reminiscent of a hawk than chicken, and is said to bless the family poultry, protecting them against birds of prey. At the end of the Perchten’s performance, she lays an egg symbolizing renewal. Guarding the henhouse against other predators is the Krapfenschnapper with foxlike mask and suit crafted from roughly two-dozen fox pelts. The Percht’s name comes from its secondary function of collecting gifts from the householders. Traditional tokens of appreciation are brandy, bacon, or donuts (Krapfen). The last is represented in the creature’s name, which has nothing to do with foxes, but instead means “donut snapper.”

Contemporary Tresterer groups are the result of revival of the practice in the decades after World War II, but the tradition’s origin is undoubtedly much older. The name, at least, appears in ethnographic surveys as early as 1841, but the form may have existed under another name before this as similar dances and elements of the costume can be found in much older records. Since the word “trestern” means “to mash,” a time-honored explanation for the custom derives the dancer’s stomping movements from the rhythms of the threshing floor, and connects this with the spirit of fertility the ritual is supposed to awaken. But modern scholars point to the Italian style of costume, seeing in it the highly decorative dress of the Venice Carnival. As the verb trestern is more commonly applied to the crushing of grapes in wine-making, it seems likely that not only the Tresterer’s costume is of Italian origin, but that the movements of the dance itself are originally inspired not by milling in Austria but wine-making in Italy.