What Costovation Is and Why It Matters

Aside from its electrifying bright purple and yellow decor, Planet Fitness looks like any other gym: There are rows and rows of elliptical machines and treadmills. There’s a basic locker room. The current top-40 hits are pumping over the speakers.

But on closer inspection, you’ll notice that there is actually a lot missing from this gym. There are no studios for yoga or spinning. There isn’t a heavy-free-weight section. There aren’t even any personal trainers. In fact, Planet Fitness forgoes many common gym features, such as:

• Towels

• A pool

• A basketball court

• Childcare

• Steam rooms, hot tubs, and saunas

• Free Wi-Fi

Even the typical gym-membership price tag is missing: while the average gym charges $52 a month, a basic Planet Fitness membership costs just $10.1

But Planet Fitness is not simply a story of a company trying to make a quick buck by slashing services and lowering prices. To understand the secret of Planet Fitness’s success, we need to look at how lowering costs and simplifying services can be a deliberate innovation strategy—one whose aim is to make the fitness experience more satisfying to its customers, not less.

Planet Fitness members don’t feel shortchanged by their barebones gym. They love that there are rows and rows of cardio machines, which means that they never have to wait to start their workout. And they don’t miss the heavy weights: Planet Fitness’s target customers don’t care for those anyway. Lunchtime workouts are stress free without personal trainers trying to sell them services. The Planet Fitness model is cheaper to run than anything else on the market, but it still ranks first in customer satisfaction—even ahead of luxury giants like Equinox.2 And the company keeps growing; at last count, Planet Fitness boasted over 7.3 million members working out in over 1,100 North American locations.

This is a company that has made careful, and sometimes difficult, choices to have a simple, low-cost offering. Along the way, it sacrificed temptations that lure other gym chains—such as personal trainers, a highly profitable add-on service that for most gyms brings in close to 10% of total revenue, or passive sources of income like rent from massage and physical therapists.3

Planet Fitness’s success highlights an underappreciated approach to innovation: purposefully offering less as a way to satisfy more. Rather than trying to compete in the overcrowded luxury fitness field, with its lavish services and hefty price tags, Planet Fitness found opportunity with a customer segment that most gyms rule out as unprofitable—casual and first-time exercisers. It then focused on a handful of things that these customers most prize, such as offering reliable workout equipment, with 24/7 access, at consistently low rates. That’s all. The company chops out the usual profit-making mechanisms adored by the industry. It seeks customers most gyms avoid, because its low operating costs make those customers far more attractive to it than to rival chains. While the rest of the fitness industry continues to plow upmarket, Planet Fitness forges its own very successful path with a no-nonsense business model that delights its boardroom as much as its customers.

This is low-cost innovation, or costovation, hard at work.

What Is Costovation?

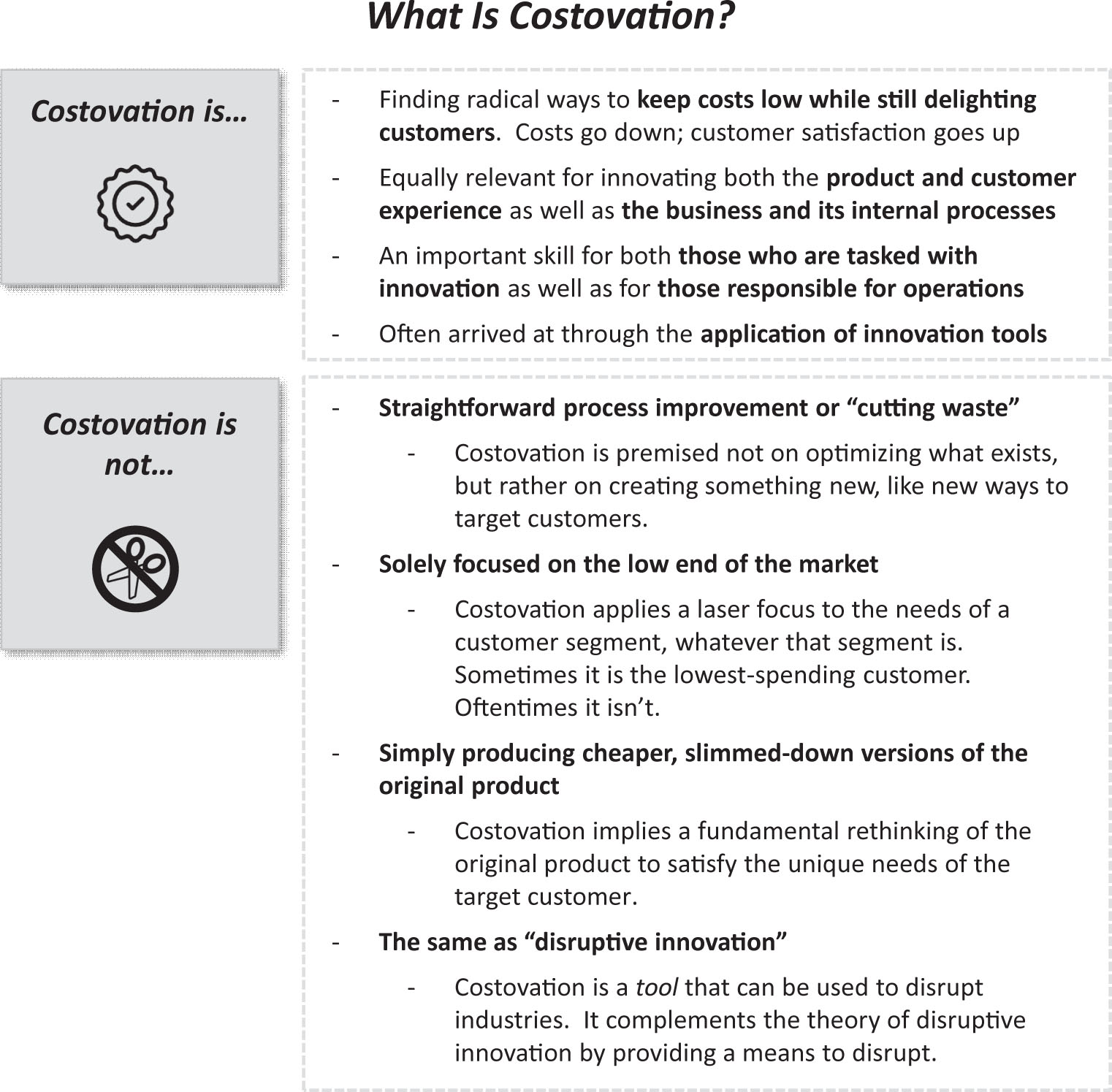

Costovation is a type of innovation that significantly compresses costs while still wowing customers. It’s about meeting or exceeding customer expectations with less. Planet Fitness with its low costs and slim offerings—but ecstatic customers—is an example of costovation. Ryanair, an ultra-budget European airline which at one time tried to charge customers for drinking water and bathroom use, is not. The difference is in customer experience. Ryanair tickets can be a grudge purchase, and purchases made with gritted teeth don’t often lead to ever-thriving companies.

To get a better sense of costovation, let’s look at an example from the hospitality industry. If you’ve ever been stuck on a six-hour layover, you know your options for comfort are bare: you can get in line for a shuttle to a local airport hotel (and plunk down your credit card for an entire night’s stay), or you can cozy up to a worn-out chair in the airport terminal. Both of those options are depressingly unappealing, especially for the frequent traveler. Enter Yotel.

Yotel is a hotel chain found in international airports like London’s Heathrow and New York’s JFK. Accommodations are often directly on-site within airport terminals, and rooms are extraordinarily small, fitting just a bed and an airplane-like bathroom. But for time-conscious travelers, Yotel offers exactly what they crave—a comfortable bed, an excellent shower, strong Wi-Fi, proximity to their next flight, and fast check-in.

Yotel doesn’t really offer much more than that, yet it’s become quite popular with experienced travelers. This travel segment is not looking for extra amenities such as a tub, a gym, or a pool. And by keeping things simple, Yotel’s back-end operations can be exceptionally lean. It uses automated kiosks for check-in and food vending, and it makes the most of its prime real estate by shrinking room sizes to tiny pod-like cabins. These cost savings enable Yotel to offer rooms that are much cheaper than a typical hotel—cheap enough that travelers use it during long layovers. At the same time, Yotel exceeds competitive offerings in critical ways, such as by providing monsoon showers for customers looking to de-grime after a long flight. Yotel runs a low-cost model, but it still nails the core needs of long-haul travelers looking for a quick place to rest and freshen up.

Many industries need a Yotel—a company that excels at offering something at a radically lower price, for a well-defined customer set. We’ve seen an increasing number of costovations in recent years, and as we’ll soon see, they are often enviably simple in nature.

Innovation and Simplicity

Innovation is typically thought to mean more: more flavors, more options, more features. What makes costovation so radical is that it flips this understanding on its head and says that sometimes the winning approach is to do less.

McDonald’s is a great example of how a less-is-more approach might have worked better. In 2004, the fast-food giant had 69 permanent items on its menu. A decade later, it had 145.4 This 110% increase was rooted in a genuine desire to keep up with trends and give customers the variety they seemed to want. Diversifying its menu was an important part of McDonald’s strategy to stay fresh, relevant, and exciting.

But expanding the menu so quickly added tremendous complexity to McDonald’s operations. To accommodate the McWrap, for instance, supply-chain managers had to source a steady annual supply of 6 million pounds of English cucumbers (not an easy feat!). Staff that were used to assembling burgers had to be trained to make a McWrap and maneuver it into its specially designed container in under 60 seconds, with just the right amount of lettuce and chicken peeking out from the top.5 Kitchen bottlenecks were further caused by limited-time-offerings items like Fish McBites, Steak & Egg Burritos, and White Chocolate Mochas. In 2013, Chief Operating Officer Tim Fenton told analysts that the chain had “overcomplicated” its menu by adding “too many new products, too fast. . . . We didn’t give the restaurants a chance to breathe.”6 Two years later, McDonald’s ran into the same problem again when it rolled out all-day breakfast, which cramped kitchen quarters as staff jostled to put an increasing number of food items onto limited grill space.7

Contrast that with Chipotle, a popular Mexican restaurant that McDonald’s partially owned until 2006. Chipotle has offered virtually the same 25-ingredient menu since the company was founded over two decades ago. Customers mix and match these 25 ingredients to create custom meals, allowing Chipotle to win on freshness and personalization while also reducing complexity in its kitchens and in its supply chain.

Chipotle’s strategy countered industry wisdom. The restaurant chain rejected limited-time offerings to boost sales and passed up low-risk/high-profit items such as coffee and cookies. They determinedly stuck to their modest menu and found a way to make it fresh and interesting to the everyday consumer. Despite its streamlined offerings, Chipotle is actually priced higher than McDonald’s—showing that you can be upmarket, low-cost, and simple all at the same time.

Companies don’t deliberately set out to make things complicated. But more often than not, they find themselves grappling with convoluted solutions to pressing problems that don’t quite get them where they want to go. The mindset that “success is a function of doing more” so dominates how companies do business that going simple is rarely treated as a viable option. And, if paring things down does happen, it’s typically through a cost-cutting campaign that has no innovation remit whatsoever.

Costovation defies this established thinking and suggests that big innovations can come from decluttering how you think, the way you do things, and what you offer. This book takes you through the nuts and bolts of how to costovate, and helps you decide when costovation is the right strategy for your organization.

Why Consider Costovation?

There are a lot of reasons why companies would want to costovate. Some are trying to surprise their competition or open up markets in industries that seem stale. Others use costovation to insulate themselves from the threat of disruptive innovation, or to build resilience against macroeconomic headwinds. Taking a birds-eye view of the field of costovation, here are three main reasons for why costovation repeatedly appears:

Cost-cutting is never easy, and there’s no more fat to trim. Costovation is a different approach to cost-cutting. Here, cost-cutting is not the overall mandate, but rather a happy byproduct in the journey toward being truly customer-centric.

Why is this important? Companies have become extraordinarily adept at squeezing blood from stone, eliminating costs large and small whenever the mandate is given—often from areas such as administrative and operating budgets. But cost-cutting can only go so far. After years of this, there’s likely little left to cut. In a 2016 study of 210 senior executives at U.S.-based Fortune 1000 companies, nearly half reported that they failed to meet their cost-reduction targets—a number that has climbed sharply from 27% in 2010 and 15% in 2008.8

The never-ending focus on cost-cutting and beating the industry cost curve—even when business is going well—has led to fatigue. We’ve heard again and again that companies need new ways to pursue transformative innovations in their operations. Costovation is one such solution.

Even in markets that feel saturated, there are still unmet needs everywhere. Although it can feel as though the world is cluttered with endless services and products, the reality is that many customers and businesses actually struggle with the products and solutions they use today. They complain about price, customer service, and the product itself; they MacGyver the products into more useful formulations. These customers will jump at opportunities to spend less if they can be well satisfied too. Costovation is a great tool for delivering on those needs.

Think of Airbnb. No one said the world needed another hotel company; there’s a hotel out there for every kind of budget and taste. But Airbnb brought a different kind of lodging proposition—one that catered to unsatisfied desires for unique living experiences and for making easy money. Thousands of people who ordinarily would have stayed at hotels were delighted with the option to stay in a cozy, unique home. And thousands of people who would ordinarily have just let their spare bedrooms lie vacant were pleased to discover that they could generate income from them.

But even with Airbnb’s meteoric rise to success, there are still countless unmet needs in hospitality that are yet to be satisfied— perhaps by the next great costovation.

There’s a large swath of customers seeking low prices. Even during the long economic expansion of the past decade, many customers—both businesses and consumers—have struggled. For instance, despite a low unemployment rate of 4%, the average hourly earnings in the U.S. grew just 2.5% in 2017—which is hardly anything at all after accounting for inflation.9 Many people are under constant pressure to make ends meet, and they need innovation relevant to them.

Moreover, we all know it is wise to be prepared for the worst, and recessions have not been abolished forever. Being prepared for macroeconomic downturns doesn’t have to mean that you can’t innovate and push forward. With costovation, you can do both.

Economies and industries can shift quickly, turning winners into losers seemingly overnight. Healthcare, for instance, used to pay high amounts for treating people when they were sick. Now, due to regulatory and economic pressures, the focus is increasingly on the opposite: paying low sums for keeping people healthy. The reversal has sent much of the industry scrambling, even while some early pioneers of this model like Kaiser Permanente are thriving in the new context.

While customer difficulties, economic downturns, and industry disruption may not be predictable, they are inevitable. Costovation enables nimble response.

What’s Next?

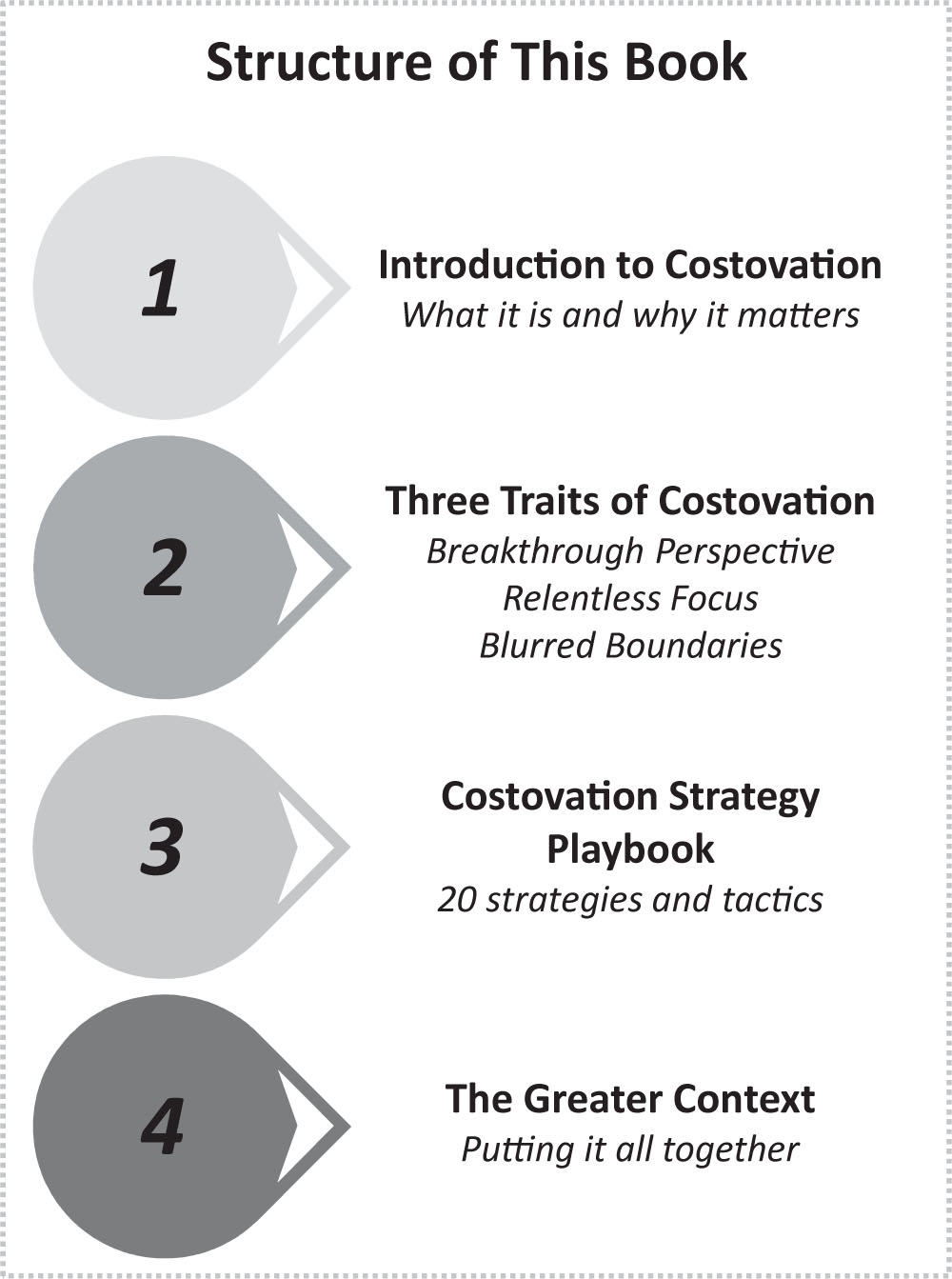

The thesis of this book is that innovation and cost-cutting—so often considered magnetic opposites—can be a powerful duo, capable of reshaping markets and creating long-term competitive advantages. The backbone of our work comes from six years of research and analysis by ourselves and our colleagues at New Markets Advisors. We carefully investigated: Are there patterns in costovation? How did these companies pull it off? And how can others do the same?

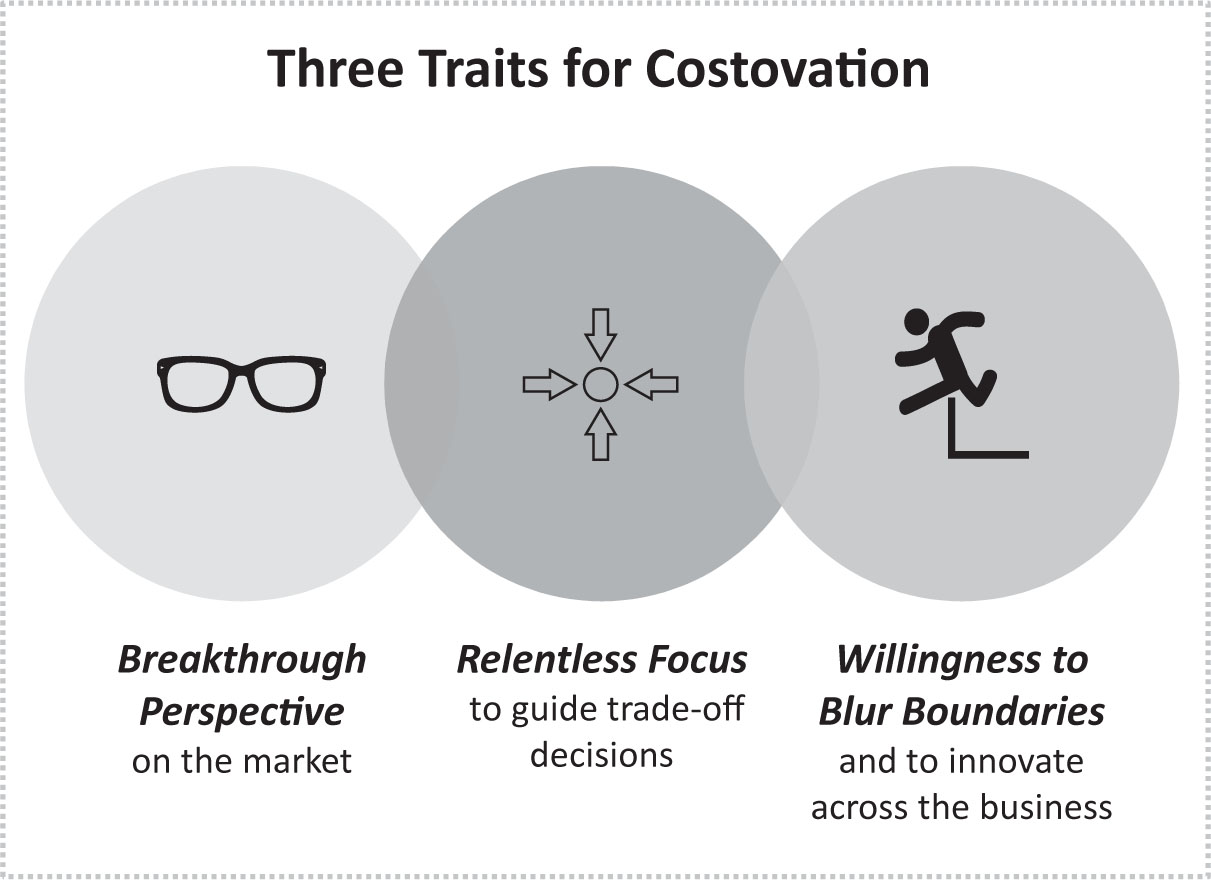

We found that companies that excel at costovation share three traits, which form the core of Part II of this book:

TRAIT 1: Breakthrough perspective. These companies had a fresh perspective on the market. They threw out assumptions and long-standing industry beliefs and viewed their market and customers in a way that no one else had. The idea behind this is straightforward: the more unique your perspective on the market, the more you can differentiate yourself.

TRAIT 2: Relentless focus. The costovation winners have relentless focus. What they concentrated on could vary; for some it was a market segment, for others it was a customer’s job to be done, and for still others it was a particular part of the business. But there was always a steadfast focus, just as in Planet Fitness’s case. The focal points were critical for guiding the companies through the many decisions and trade-offs they had to make.

TRAIT 3: Willingness to blur boundaries. The most obvious place to innovate is on the product. But companies which excel at costovation—that is, the companies using costovation to shake up their markets—also took magnifying lenses to how their offerings were made, delivered, and sold. These companies innovated across different areas of the business.

![]()

In Part III, we look at the mechanics of different costovation approaches. We delve into twenty costovation strategies—identifying what they are, when to use them, how they have been used in different contexts, and how you can get started.

Part IV is about the bigger picture. It provides a diagnostic for determining when costovation makes sense for an industry, examines how costovation fits into your broader business strategy, and finishes with a detailed checklist of how to begin.

Costovation is not a new thing, even if the business literature has largely ignored the phenomenon. Companies have been costovating for decades, and they have used established innovation techniques to help them get there. Our role has been to capture their learnings and show how to apply innovation methods toward a new goal: to wow customers with business processes and products that cost less.