![]()

Wall Street’s Addiction to Forecasting

MAYBE YOU REMEMBER when American folk songs were prominent, or you discovered them on your own and just liked what you heard. You are likely, then, to have heard the name of Woody Guthrie. (And everyone knows his anthem, “This Land Is Your Land.”) He came out of hard times in Oklahoma during the Great Depression, and his songs celebrated the nation’s down and out. His 1939 song “The Ballad of Pretty Boy Floyd” included the line “Some will rob you with a six-gun, and some with a fountain pen,”1 a biting reference to the millions of people who were losing their farms and homes to the foreclosing banks of the time. Now substitute computer spreadsheets for a fountain pen, perhaps with an added stanza or two for some contemporary wrinkles such as collateralized debt obligations, credit default swaps, toxic assets, and exotics, and the lyrics ring true today.

The national debate on whether there should be more or less regulation and government spending rolls on, with no consensus in sight. It seems that lately, economists can’t agree about much. (See page 155 for more on this.) At any rate, it’s pretty obvious what we’re all wondering: how did the experts ever get us into such a mess?

By this time you might feel a little as though you’ve just come off basic training on Parris Island or running the New York Marathon. We’ve moved at a brisk pace through some of the important details of why an understanding of investors’ psychology and the intellectual clash over efficient markets is essential to give you the edge when you go into the market wars.

We’ve detailed the formidable conceptional obstacle course that each presents but that you can come through with flying colors: investor psychology, because it can give you an understanding of how to protect and enhance your savings; efficient-market theory, because, though a failing hypothesis, it can provide deadly results if you’re not aware of the ways it can strike. I hope that the two opening sections have provided you with at least a bare-bones understanding of their importance for what comes next in our psychological investor program.

In this chapter we will begin to lay out why contemporary investment theory has proved so disappointing over time. It’s not because, as the EMH theorists assume, we are rational automatons, but quite the opposite, because we are human and succumb to human errors—errors that standard investment theory does not take account of.

Over the last fifty years or so, cognitive psychology has moved in a strikingly different direction from economics theorizing. While economists were embracing a conceptually useful reduction—rational man—psychologists were out to establish an increasingly complex picture of how humans processed information. Spurred by rapid advances in cognitive psychology, sociology, and related fields from the 1980s on, psychologists looked more and more at what differentiated the human mind from machine-based computer logic.

Even as computers seemed to become capable of mimicking aspects of human cogitation, the fact remains that no computer can rival the human mind for its overall capabilities. However, our mental processes, as we have seen, do not work with the flawless logic of computers, so psychologists have investigated the limits of expert knowledge and information handling. What they found was the often subliminal reasons why even experts fail—and why the rest of us aren’t going to do much better.

Scores of studies have made it clear that experts’ failure extends far beyond the investment scene. It’s a basic problem in human information-processing capabilities. Current work indicates that our brains are serial or sequential processors of data that can handle information reliably in a linear manner—that is, we can move from one point to the next in a logical sequence. In building a model ship or a space shuttle, there is a defined sequence of procedures. Each step, no matter how complex the technology, advances from the preceding step to the next step until completion.

The type of problem that proved so difficult to professionals is quite different, however; here configural (or interactive) reasoning, rather than linear thinking, is required. In a configural reasoning problem, the decision maker’s interpretation of a piece of information changes depending on how he or she evaluates other inputs. Take the case of a security analyst: when two companies have the same trend of earnings, the emphasis placed on growth rates will be weighed quite differently depending on the outlooks for their industries, revenue growth, profit margins, and returns on capital, and the host of analytical criteria we looked at previously. The analyst’s evaluation will also be tempered by changes in the state of the economy, the interest rate level, and the companies’ competitive environment. Thus, to be successful, analysts must be adept at configural processing; they must integrate and weigh scores of diverse factors, and, if one factor changes, they must reweigh the whole assessment.

As with juggling, each factor is another ball in the air, increasing the difficulty of the process. Are professionals, in or out of the investment field, capable of the intricate analysis their methods demand? We have seen how difficult this task is and why so many people unconsciously turn to experiential reasoning instead of the rational-analytical methods that are prescribed.

A special technique was designed, using a statistical test called analysis of variance, or ANOVA, to evaluate experts’ configural capabilities. In one such study, nine radiologists were given a highly configural problem: deciding whether a gastric ulcer was malignant.2 To make a proper diagnosis, a radiologist must work from seven major cues either present or absent in an X-ray. These can combine to form fifty-seven possible combinations. Experienced gastroenterologists indicated that a completely accurate diagnosis can be made only by configurally examining the combinations formed by the seven original cues.3

Although the diagnosis requires a high level of configural processing, the researchers found that in actual practice, it accounted for a small part of all decisions, some 3 percent. More than 90 percent came from serially adding up the individual symptoms.

A similar problem is deciding whether a psychiatric inpatient is to be allowed to leave the hospital for short periods. The hospital staff has to consider six primary cues that can be present or absent (for example, does the patient have a drinking problem?) and sixty-four possible interactions. In another study, nurses, social workers, and psychologists showed little evidence of configural thinking, although it was essential to reaching the optimum solution.4 In a third study, thirteen clinical psychologists and sixteen advanced graduate students attempted to determine whether the symptoms of 861 patients were neurotic or psychotic, a highly configural task. The results were in line with the first two examples.5

Curious as to what he would find in the stock market, Paul Slovic tested the importance of configural (or interactive) reasoning in the decisions of market professionals. In one study he provided thirteen stockbrokers and five graduate students in finance with eight important financial inputs—the trend of earnings per share, profit margins, outlook for near-term profits, and so on—that they considered significant in analyzing companies. They had to think configurally to find the optimum solution. As it turned out, however, configural reasoning, on average, accounted for only 4 percent of the decisions made—results roughly equivalent to those of the radiologists and psychologists.

Moreover, what the brokers said about how they analyzed the various inputs differed significantly from what they did.6 For example, a broker who said that the most important trend was earnings per share might actually have placed greater emphasis on near-term prospects. Finally, the more experienced the brokers, the less accurate their assessment of their own scales of weighting appeared to be. All in all, the evidence indicates that most people are weak configural processors, in or out of the marketplace. So it turns out that human minds—as I’m sure you’ve suspected—are not hardwired anything like the way computers are.

As we saw in our first look at information processing in chapter 3, Herbert Simon more than fifty years ago wrote extensively on information overload. Under certain conditions, experts err predictably and often; in fields as far apart as psychology, engineering, publishing, and even soil sampling, all of them make the same kinds of mistakes. The conditions for such errors are as fertile in the stock market as anywhere.

I briefly mentioned that the vast storehouse of data about companies, industries, and the economy mandated by current investment methods may not give the professional investor an extra “edge.” When information-processing requirements are large and complex analysis is necessary to integrate it, the rational system, which is deliberative and analytical, is often subtly overridden without the professional’s knowledge by the experiential system. Inferential processing delicately bypasses our rational data banks. As we’ve seen, ingesting large amounts of investment information can lead to worse rather than better decisions because the Affect working with other cognitive heuristics, such as representativeness and availability, takes over.

In the next chapter, you’ll see that forecasting, the heart of security analysis, which selects stocks precisely by the methods we are questioning, misses the mark time and again. We’ll also see that the favorite stocks and industries of large groups of professional investors have fared worse than the averages for many decades. This is the primary reason for the subpar performance of professionals over time that was witnessed by the efficient-market researchers in Part II, rather than the EMH myth of rational automatons who make flawless decisions that keep markets efficient.

To outdo the market, then, we must first have a good idea of the forces that victimize even the pros. Once those forces are understood, investors can build defenses and find routes to skirt the pitfalls.

Under conditions of complexity and uncertainty, experts demand as much information as possible to assist them in their decision making. Seems logical. Naturally, there is tremendous demand for such incremental information on the Street because investors believe that the increased dosage gives them a shot at the big money. But, as I have indicated earlier, that information “edge” may not help you. A large number of studies show rather conclusively that giving an expert more information doesn’t do much to improve his judgment.7

In a study of what appears to be a favored class of human guinea pigs, clinical psychologists were given background information on a large number of cases and asked what they thought their chances were of being right on each one. As the amount of information increased, the diagnosticians’ confidence rose dramatically, but their accuracy continued to be low. At a low level of information, they estimated that they would be correct 33 percent of the time; their accuracy was actually 26 percent. When the information was increased fourfold, they expected to be correct in 53 percent of the cases; in fact, they were right 28 percent of the time, an increase of only 2 percentage points.

Interestingly, the finding seems universal: only a marginal improvement in accuracy occurs as increasing amounts of new information are heaped on. The same results were obtained using racetrack handicappers. Eight veteran handicappers were progressively given five to forty pieces of the information they considered important in picking winners. One study showed that their confidence rose directly with the amount of information received, but the number of winners, alas, did not.8

As the studies demonstrate, people in situations of uncertainty are generally overconfident on the basis of the information available to them, believing they are right much more often than they are. One of the earliest demonstrations of overconfidence involved the predictive power of interviews. Many people think a short interview is sufficient for making reasonable predictions about a person’s behavior. Analysts, for example, frequently gauge company managers through meetings lasting less than an hour. Extensive research indicates that such judgments are often wrong. One interesting example took place at the Harvard Business School. The school thought that by interviewing candidates beforehand, it could recruit students who would earn higher grades. In fact, the candidates selected that way did worse than students accepted on their academic credentials alone. Nevertheless, superficial impressions are hard to shake and often dominate behavior.

Overconfidence, according to cognitive psychologists, has many implications. A number of studies indicate that when a problem is relatively simple to diagnose, experts are realistic about their ability to solve it. When the problem becomes more complex, however, and the solution depends on a number of hard-to-quantify factors, they became overconfident of their ability to reach a solution (accuracy 61 percent). If the task is impossible—for example, distinguishing European from American handwriting—they became “superoverconfident” (accuracy 51 percent).9

A large number of other studies demonstrate that people are consistently overconfident when forming strong impressions from limited knowledge. Lawyers, for example, tend to overestimate their chances of winning in court. If both sides in a court case are asked who will win, each will say its chances of winning are greater than 50 percent.10 Studies of clinical psychologists,11 physicians,12 engineers,13 negotiators,14 and security analysts15 have all shown they are far too confident in the accuracy of their predictions. Clinical psychologists, for instance, believed their diagnosis was accurate 90 percent of the time, when in fact it was correct in only 50 percent of cases. As one observer said of expert prediction, “[It] is often wrong but rarely in doubt.”

The same overconfidence occurs when experienced writers or academics working on books or research papers estimate the time of completion. The estimates are invariably overconfident; the books and papers are completed months or years behind schedule, and sometimes they are not completed at all.

Studies in cognitive psychology also indicate that people are overconfident that their forecasts will be correct. The typical result is that respondents are correct in only 80 percent of the cases when they describe themselves as 99 percent sure16—not what you’d exactly want in a stress test or another health-critical test result.

The question becomes even more interesting when experts are compared with laypeople. A number of studies show that when the predictability of a problem is reasonably high, the experts are generally more accurate than laypeople. Expert bridge players, for example, proved much more capable of assessing the odds of winning a particular hand than average players.17 When predictability is very low, however, experts are more prone to overconfidence than novices. When experts predict highly complex situations—for example, the future of troubled European Union countries such as Portugal and Greece, the impact of religious fundamentalists on foreign policy in the Middle East, or the movement of the stock market—they usually demonstrate overconfidence. Because of the richness of information available to them, they believe they have the advantage in their area of expertise. Laypeople with a very limited understanding of the subject, on the other hand, are normally more conservative in their judgments.18

Overconfident experts are legion on the investment scene. Wall Street places immense faith in detailed analysis by its experts. In-depth research houses turn out thousands upon thousands of reports, each running to a hundred pages or more and sprinkled with dozens of tables and charts. They set up Washington and international listening posts to catch the slightest whiff of change in government policies or economic conditions abroad. The latest turn here, now being investigated by the SEC, is to hire former corporate executives from major companies they follow to give them “the real scoop” on “what’s going on” inside. Scores of conferences are naturally called to provide money managers with this penetrating understanding. All too often they have proved to be “wrong in depth,” as one skeptic put it.

The more detailed the level of knowledge, the more effective the expert is considered to be. Despite widespread concerns from 2005 through 2007, major bankers and investment bankers, including Citigroup, Lehman Brothers, and Goldman Sachs, stated emphatically that there was no sign of a bubble in the housing market. They continued to sell subprime toxic waste, including part of their own inventory, by the tens of billions of dollars to their own clients, until the subprime markets completely dried up in mid-2007. To survive, many were forced to ask for a bailout, which was organized by Hank Paulson, the Treasury secretary and ex-CEO of Goldman Sachs. As with the clinical psychologists and the handicappers, the information available had little to do with accurately predicting the outcome.

The inferior investment performance we’ve seen, as well as more that we will look at next, was based on just such detailed research. To quote a disillusioned money manager of the early 1970s, “You pick the top [research] house on the Street and the second top house on the Street—they all built tremendous reputation, research-in-depth, but they killed their clients.”19 Nothing much has changed.

I offer a Psychological Guideline for investing that is applicable in almost any other field of endeavor:

PSYCHOLOGICAL GUIDELINE 7: Respect the difficulty of working with a mass of information. Few of us can use it successfully. In-depth information does not translate into in-depth profits.

I hope it is becoming apparent that configural relationships are extremely complex. Stock market investors are dealing not with twenty-four or forty-eight relevant interactions but with an astronomical number. As we have already seen, far fewer inputs can overtax the configural or interactive judgment of experts. Because most Wall Street experts, like those elsewhere, are unaware of these psychological findings, they remain convinced that their problems can be handled if only those few extra facts are available. They overload with information, which doesn’t help their thinking but makes them more confident and therefore more vulnerable to making serious errors. The difficulty of configural reasoning is unfortunately almost unknown by both investors and EMH theorists.

As we saw earlier, the phenomenon of overconfidence seems to be both an Affect and a cognitive bias. In other words, the mind is probably designed to extract as much information as possible from whatever is available. The filtering process, as we saw in chapter 3, is anything but a passive process that provides a good representation of the real world. Rather, we actively exclude information “that is not in the scope of our attention.”20 It thus provides only a small part of the total necessary to build an accurate forecast in uncertain conditions.

Evaluating stocks is no different. Under conditions of anxiety and uncertainty, with a vast interacting web of partial information, it becomes a giant Rorschach test. The investor sees any pattern he or she wishes. In fact, according to recent research in configural processing, investors can find patterns that aren’t there—a phenomenon called illusory correlation.

Trained psychologists, for example, were given background information on psychotics and were also given drawings allegedly made by them but actually prepared by the researchers. With remarkable consistency, the psychologists saw in the drawings the cues that they expected to see: muscular figures drawn by men worried about their masculinity or big eyes by suspicious people. But not only were those characteristics not stressed in the drawings; in many cases they were less pronounced than usual.21 Because the psychologists focused on the anticipated aberrations, they missed important correlations that were actually present.22

Investors attempt to simplify and rationalize complexity that seems at times impenetrable. Often they notice facts that are simply coincidental and think they have found correlations. If they buy the stock in the “correlation” and it goes up, they will continue to invest in it through many a loss. The market thus provides an excellent field for illusory correlation. The head-and-shoulders formation on a chart cuts through thousands of disparate facts that the chartist believes no one can analyze; buying growth stocks simplifies an otherwise bewildering range of investment alternatives. Such methods, which seemed to work in the past, are pervasive on Wall Street. The EMH theorists’ search for the correlation between volatility and returns that the theory demands seems to be another example. The problem is that some of the correlations are illusory and others are chance. Trusting in them begets error. A chartist may have summed it up most appropriately: “If I hadn’t made money some of the time, I would have acquired market wisdom quicker.”

Which brings us to the next Psychological Guideline, one that may at first glance appear simple but is important and will prove harder to follow than you may think!

PSYCHOLOGICAL GUIDELINE 8: Don’t make an investment decision based on correlations. All correlations in the market, whether real or illusory, will shift and soon disappear.

This is important for the investor: if analysts are generally optimistic, there will be a large number of disappointments created not by events but by initially seeing the company or industry through rose-colored glasses.

The late Amos Tversky, a pioneer in cognitive psychology, researched expert overoptimism and overconfidence in the stock market. According to Tversky, “In one study, analysts were asked such questions as what is the probability that the price of a given stock will exceed $X by a given date. On average, analysts were 80% confident but only 60% accurate in their assessments.”23 The study was repeated numerous times.

In other studies, analysts were asked for their high and low estimates of the price of a stock. The high estimate was to be a number they were 95 percent sure the actual price would fall below; the low estimate was the price they were 95 percent sure the stock would remain above. Thus, the high and low estimates should have included 90 percent of the cases, which is to say that if the analysts were realistic and unbiased, the number of price movements above and below this range would be 10 percent. In fact, the estimates missed the range 35 percent of the time, or three and a half times as often as estimated.

Tversky went on to note that “rather than operating on rational expectations”—with total logic, unaffected by behavior, as efficient-market theory assumes investors do—“people are commonly biased in several directions: they are optimistic; they overestimate the chances that they will succeed, and they overestimate their degree of knowledge, in the sense that their confidence far exceeds their ‘hit rate.’”24

Tversky was queried about overconfidence at an investment behavioral conference in 1995 that I attended and also spoke at. The questioner asked what he thought of the fact that analysts were not very good at forecasting future earnings. He responded, in part, “From the standpoint of the behavioral phenomena . . . analysts should be more skeptical of their ability to predict [earnings] than they usually are. Time and time again, we learn that our confidence is misplaced, and our overconfidence leads to bad decisions, so recognizing our limited ability to predict the future is an important lesson to learn” (italics mine).25

He was asked at the same conference if analysts and other professional investors learn from their experiences. He replied that “unfortunately cognitive illusions are not easily unlearned. . . . The fact that in the real world people have not learned to eliminate . . . overconfidence speaks for itself.”26

I’m afraid we’re overconfident that we can overcome our tendency to be overconfident by simply recognizing that we tend to be overconfident. It’s just not that simple, alas.

Given what we just saw, how optimistic do you think analysts’ earnings estimates are? Jennifer Francis and Donna Philbrick studied analysts’ estimates for some 918 stocks from the Value Line Investment Survey for the 1987–1989 period.27 Value Line is well known on the Street for near-consensus forecasts. The researchers found that analysts were optimistic in their forecasts by 9 percent annually, on average. Again, remembering the devastating effect of even a small miss on high-octane stocks, these are very large odds against investors looking for ultraprecise earnings estimates.

The overoptimism of analysts is brought out even more clearly by I/B/E/S, the largest earnings-forecasting service, which monitors quarterly consensus forecasts on more than seven thousand domestic companies. Despite these allowable quarterly estimate changes, analysts tend to be optimistic, according to I/B/E/S. What seems apparent is that analysts do not sufficiently revise their optimistically biased forecasts in the first half of the year and then almost triple the size of their revisions, usually downward, in the second half. Even so, their forecasts of earnings are still too high at year-end.

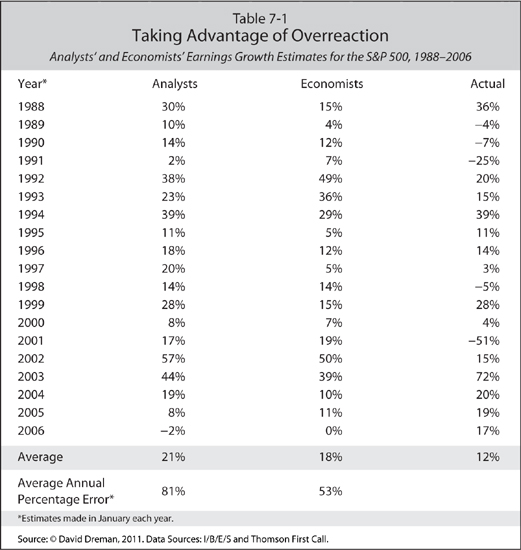

A study that Eric Lufkin28 of Morgan Stanley and I collaborated on for my Forbes column some years back (January 26, 1998) provided further evidence of analysts’ overoptimism. I updated the study to the end of 2006 in Table 7-1. The study measures analysts’ and economists’ estimates against the actual S&P reported earnings from 1988 to 2006, a nineteen-year period, which saw more than its share of bubbles and crashes, as well as economic booms and recessions. Analysts make “bottom-up” estimates; that is, they look at all the important fundamentals of a company and then make their estimate for a stock. They forecast company by company and then the companies are added up, with the proper weighting in the S&P 500 index for each, to arrive at a forecast. Economists, on the other hand, make “top-down forecasts”; that is, they look at the economy and then decide how their overall forecasts will trickle down to individual company estimates. A glance across each year shows the percentage increase or decrease in earnings the analysts forecast in column 2, those the economists forecast in column 3, and the actual increase or decrease in earnings that the S&P 500 showed for the year in column 4.

What is striking is how overly optimistic the estimates by both analysts and economists actually are. To be fair, let’s look at analysts’ and economists’ estimates over the entire nineteen years of the study and then compare them with the actual earnings of the S&P 500. As Table 7-1 shows, the average estimate for analysts was a 21 percent increase in earnings, the average for economists was 18 percent, and the actual earnings increase for the S&P was 12 percent. As column 3 demonstrates, economists—supposedly charter members of the “dismal science”—made earnings forecasts that were overoptimistic by an astounding 53 percent (over S&P reported earnings) annually on average over the nineteen-year period. Could anything be worse? Why, yes: analysts were overoptimistic by 81 percent annually on average over that time, an enormously high miss. The study evidence: earnings forecasting is neither an art nor a science but a lethal financial virus.

What makes analysts so optimistic? The subject is anything but academic because it is precisely this undue optimism that induces many people, including large numbers of pros, to buy stocks they recommend. As we have seen in the recent examples and will see more thoroughly in the chapters ahead, unwarranted optimism exacts a fearful price. A Psychological Guideline is again in order:

PSYCHOLOGICAL GUIDELINE 9: Analysts’ forecasts are usually overly optimistic. Make the appropriate downward adjustment to your earnings estimate.

Now, there are people with outstanding gifts for abstract reasoning who can cut through enormously complex situations. Every field has its William Miller or Bill Gross. But such people are rare. It seems, then, that the information-processing capabilities and the standards of abstract reasoning required by current investment methods are too complicated for the majority of us, professional or amateur, to use accurately.

At this point, you might be wondering if I’m exaggerating the problems of decision making and forecasting in the stock market. The answer, I think, can be found by considering the favorite investments of market professionals over time.

Consider a large international conference of institutional investors held at the New York Hilton in February 1968. Hundreds of delegates were polled about the stock that would show outstanding appreciation that year. The favorite was University Computing, the highest-octane performer of the day. From a price of $443, it dropped 88 percent in less than twelve months. At an Institutional Investor conference in the winter of 1972, the airlines were expected to perform the best for the balance of the year. Then, within 1 percent of their highs, their stocks fell 50 percent that year in the face of a sharply rising market. The conference the following year voted them a group to avoid. In another conference, in 1999, a large group of professionals polled picked Enron as the outstanding performer for the next twelve months. We all know what happened to that hot stock.

Are those results simply chance? In an earlier book, The New Contrarian Investment Strategy (1982), I included fifty-two surveys of how the favorite stocks of large numbers of professional investors had fared over the fifty-one-year period between 1929 and 1980. The number of professionals participating ranged from twenty-five to several thousand. The median was well over a hundred. Wherever possible, the professionals’ choices were measured against the S&P 500 for the next twelve months.*43

Eighteen of the studies measured the performance of five or more stocks the experts picked as their favorites.29 Diversifying into a number of stocks, instead of one or two, will reduce the element of chance. Yet the eighteen portfolios chosen underperformed the market on sixteen occasions! This meant, in effect, that when a client received professional advice about those stocks, they would underperform the market almost nine times out of ten. Flipping a coin would give you a fifty-fifty chance of beating the market.

The other thirty-four samples did little better. Overall, the favorite stocks and industries of large groups of money managers and analysts did worse than the market on forty of fifty-two occasions, or 77 percent of the time.

But those surveys, although extending over fifty years, ended in 1980. Has expert stock picking improved since then? The Wall Street Journal conducted a poll on whether the choices of four well-known professionals could outperform the market each year between 1986 and 1993. At the end of the year, four pros gave their five favorite picks for the next year to John Dorfman, the editor of the financial section, who reviewed them twelve months later, eliminating the two lowest performers and adding two fresh experts. In sixteen of thirty-two cases, the portfolios underperformed the market—a somewhat better result than in the past, but no better than the toss of a coin.30*44

Table 7-2 gives the results of all such surveys that I found through 1993. As the table shows, only 25 percent of the surveys of the experts’ “best” stocks outperformed the market. The findings startled me. Though I knew that experts make mistakes, I didn’t know that the magnitude of the errors was as striking or as consistent as the results make evident.

But some of the studies go back to the 1920s, and the last one ends in 1993. Has stock picking improved since then? After all, in the past fifteen years, the performance of professional investors has been more carefully scrutinized than ever before. As we saw in chapters 1 and 2, money managers as a group have not outperformed the market. Another study done by Advisor Perspectives for the ten years ending December 31, 2007, analyzed how stocks in the S&P domestic indices performed against the S&P benchmark index. As Table 7-3 shows, using one of the S&P indices as a benchmark, the S&P indices outperformed the stocks in six of the nine sectors and tied once.

In only one case, the S&P 500/Citigroup Growth, did the mutual funds significantly outperform the S&P index. In brief, the averages beat the money managers two-thirds of the time over the ten-year period.

Finally, for the five years ending in 2009, the S&P 500 Index outperformed 60.8 percent of actively managed large-cap U.S. equity funds, the S&P MidCap 400 index outperformed 77.2 percent of midcap funds, and the S&P Small-Cap 600 index outperformed 66.6 percent of small-cap funds.

The studies now in place as a group for more than seventy-five years clearly demonstrate just how badly money managers and analysts underperformed the market. They also clearly demonstrate that professional investors, in the large majority of cases, were tugged toward the popular stocks of the day, usually near their peaks, and, like most investors, steered away from unpopular, underpriced issues, as the subsequent year’s market action indicated. Also interesting is that one industry—technology—was favored over the years, although there were dozens to choose from. And it was favored so unsuccessfully! Experts’ advice, in these surveys at least, clearly led investors to overpriced issues and away from the better values.

What can we make of these results? The number of samples seems far too large for the outcome to be simply chance. The evidence indicates a surprisingly high level of error among professionals in choosing stocks and portfolios over six and a half decades.

The failure rate among financial professionals, at times approaching 90 percent, indicates not only that errors are made but that under uncertain conditions there must be systematic and predictable forces working against unwary investors.

Yet again, such evidence is obviously incompatible with the central assumption of the efficient-market hypothesis.31 Far more important is the practical implication of what we have just seen, another plausible explanation of why fundamental methods often don’t work. Investment theory demands too much from people as configural and information processors. Under conditions of information overload, both within and outside markets, our mental tachometers surge far above the red line. When this happens, we no longer process information reliably. Our confidence rises as our input of information increases, but our decisions do not improve. This leads to another Psychological Guideline.

PSYCHOLOGICAL GUIDELINE 10: Tread carefully with current investment methods. Our limitations in processing complex information prevent their successful use by most of us.

Though it is probably true that experts do as poorly under other complex circumstances, market professionals unfortunately work in a goldfish bowl. In no other profession I am aware of is the outcome of decisions so easily measurable.

In examining the stock-picking record of money managers and other market pros, a critical question is: how accurate are analysts’ earnings estimates? Those are the key elements underlying stock selections and the heart of investing as it is practiced today. That’s the question to be examined next. The results of some very thorough studies on the accuracy of the top security analysts, the cream of the crop, will surprise you.