4. Sound

Ask yourself which sense is the most important when it comes to determining your experience of food and drink. Most people will mention taste first. Smell will rank pretty highly too, of course. Some might talk about what a food looks like, and maybe even the mouthfeel and oral texture. But virtually no one, be they sensory scientist, chef or regular consumer, talks about sound. However, as you will see in this chapter, what we hear when we eat and drink—even the noises of food preparation, the rattling sounds of product packaging or loud background music—plays a much more important role than any of us realize. Sound, in other words, is the forgotten flavor sense.

The sounds of preparation

What would go through your mind if you were sitting in a fancy restaurant and you suddenly heard the unmistakable “ding” of the microwave? It would be pretty disconcerting! I would argue that the sounds of food and beverage preparation are important precisely because they help set our expectations. No wonder, then, that so many people deliberately try to disable the microwave’s distinctive sound because of the negative impression that it conveys to all who hear it (especially in a restaurant setting). Go online and you’ll be amazed how many blogs and discussion groups there are complaining about this sound and requesting help to turn it off. Large electronics manufacturers such as GE have, in recent years, been working on redesigning it. (Perhaps, though, attitudes are changing, at least in the home environment; according to the results of a recent survey, a third of those questioned said that they wouldn’t mind if served a microwaved meal at a dinner party.) Of course, the sounds of food cooking can also capture our attention. Just think about all of the desirable food preparation sounds that may have you salivating before you can say “dinnertime.” In fact, one of the classic observations in the field of psychology made by the Russian scientist Ivan Pavlov, way back in the 1920s, was that the dogs he was studying started salivating in response to the sound of the bell used to alert them to the arrival of food. The dogs had soon come to associate the sound of the bell with the delivery of food.

Just take the grinding, gurgling, spluttering and sizzling noises emanating from a coffee machine. These sounds are diagnostic, i.e., they are rich in clues about the probable tasting experience that is to follow. Even the screeching and squealing of the hot-air bubbles that make the milk froth provide information, at least for those who know how to listen. It’s the change in pitch that tells the barista when the milk in the jug has reached the right temperature. And if you think that’s impressive, what about the guy who says that he can distinguish a hundred different brands of beer based simply on the sound of the bubbles when a drink is poured into a glass!

Klemens Knöferle, a former post-doc in my Oxford lab, conducted a study in which he systematically influenced what people said about a cup of Nespresso coffee simply by filtering the sounds made by the machine as it turned those colorful pods into cups of coffee. As he enhanced the harsher, higher-pitched noises, people said that the coffee didn’t taste so good. When he cut them, suddenly taste ratings went up. So it’s no wonder that so many manufacturers are now trying to engineer the “right” noises into their machines. They are, in other words, slowly catching up with all the car companies out there who, for decades, have been modifying the design of everything from the sound the car door makes when it closes through to the noise made by the engine as heard by the driver inside the vehicle. Do you remember the iconic Volkswagen “Sounds just like a Golf” adverts?

Some innovative chefs have started to work creatively with the sounds of preparation. This is what you would have experienced had you been lucky enough to score a table at Mugaritz in San Sebastián in 2015: at one point during the meal, mortars and pestles were brought out from the kitchen, and diners were encouraged to grind their own spices prior to a hot broth being poured into each and every mortar. Just imagine a roomful of diners sitting in a prestigious two-Michelin-starred restaurant, all grinding their spices in synchrony, creating a resonant sound that fills the room. All of the guests sitting at their separate tables united, at least for a moment, by the playful sounds of food preparation.

One Swedish composer, Per Samuelsson, has made something of a career composing with these sorts of food preparation sounds. He is often to be found recording the peeling, chopping, slicing, dicing, grinding, shaking and stirring noises in a busy kitchen. The young Swede then turns those kitchen sounds into a musical composition that is played back to diners while they eat the fruits of the chefs’ labor. These compositions are intended to highlight the often unacknowledged effort involved in creating the food that we consume, while at the same time delivering an immersive multisensory environment, one that is designed to enhance the meal experience. Meanwhile, Massimo Bottura, voted the world’s top chef in 2016, was recently recorded in an anechoic chamber. The aim? To capture all of the sounds of him making lasagne, the favourite comfort food of his childhood.

It started with a crisp

Back in 2008, Max Zampini and I were awarded the Ig Nobel Prize for Nutrition for our groundbreaking work on the “sonic chip” (see Figure 4.1). Yes, I know what you are thinking: completely preposterous. Ten of these prizes are awarded every year to a select bunch of international scientists for research that, on the face of it, sounds crazy, ridiculous or preferably both. But the point is that this work, which hopefully makes you laugh first, is actually serious. And getting the prize garners a huge amount of publicity for the winning researchers. Believe it or not, a decade after receiving the award, I am still fielding inquiries on a monthly basis. (This despite my family’s incredulity—“Not the crisps again,” they moan whenever they see the story resurface in the press.) Film crews from around the world periodically descend on the lab, wanting to recreate the magic moment when, simply by changing the sound of the crunch, we were able to change people’s perception of the crunchiness and freshness of the crisps (or potato chips, if you are reading this in North America). Truly, my life has not been the same since.

Figure 4.1. My former student Max Zampini (now the esteemed Prof. Zampini) demonstrating the “sonic chip” experiment on the front cover of Annals of Improbable Research.

When we first published our results in what, even by academic standards, was a fairly obscure outlet, we thought that they were important, certainly, but nothing out of the ordinary. While Unilever, who funded the study, were interested in our findings, it was hard to see who else might get excited by them. And, if you are wondering why exactly Unilever would fund a project using one of their competitor’s products (at the time, Pringles were owned by P&G), well, the answer is that Pringles are ideal for gastrophysics research. Why so? Because they are all exactly the same size and shape. So you can be sure that any change in people’s responses must be attributable to the sound manipulation that you have introduced, not to any individual differences in the crisps themselves. And Pringles have another practical advantage: they are large enough that people don’t normally put them in their mouths in one go. (You don’t, do you?) Hence the relative contribution of air-conducted to bone-conducted sounds in the overall multisensory tasting experience is enhanced.

Basically, we discovered that, solely by boosting the high-frequency sounds that people hear when they bite into a Pringle, we could make them seem around 15% crunchier and fresher than when we cut those sounds. Of course, you might reasonably expect that chefs would be less influenced by such superficial sound modifications of the food they eat. But that turns out not to be the case, at least not if the trainee chefs at the Leith cookery school in London were anything to go by. When we tested them for a BBC TV show a few years ago, they were so busy concentrating on the texture of the crisps that they were just as easily fooled as the Oxford undergraduates who provided the subject matter for our original study.

You can play exactly the same sonic tricks with apples, celery, carrots or, in fact, with any other noisy food, be it dry, like crisps and crackers, or moist, like fruit and vegetables. In one recent study, this time conducted in northern Italy, ratings of the crispness and hardness of three varieties of apple were systematically modified by changing people’s biting sounds. This crossmodal illusion is important for a couple of reasons. For one thing, it provides one of the most robust demonstrations that what we hear really does influence what we taste. And it turns out that this particular crossmodal effect works just as well even when you know exactly what is going on. It continues to work no matter how many sonically enhanced chips you’ve bitten into too. I should know, having crunched more than most—all in the name of science. In other words, the sonic chip illusion is an automatic multisensory effect, as my colleagues in the cognitive neurosciences would say.

Can the sonic chip change product innovation?

But perhaps the more important consequence of our “ground-breaking” research is that this kind of neuroscience-inspired testing protocol has now been adopted by many of the world’s largest food companies. The virtual prototyping approach developed here in Oxford, where we assess how consumers respond to augmented reality products (rather than real product prototypes), allows these companies to figure out how people would respond if their products were to have added crunch or crackle, say. Importantly, the food and beverage companies can do this without having to go into the development kitchens and make a whole host of new products that actually do sound noticeably different from each other. This, the traditional approach, tends to make for a much slower and more effortful development process, especially when the feedback from the tasting panel, as is often the case, is that they didn’t like any of the new variants that the researchers worked so hard to create. On hearing such news, they have to go back to the kitchens, shoulders slumped and heads drooping, and prepare a whole new set of samples. This is product innovation, yes. But it can be painfully slow!

By contrast, having the testing panel evaluate virtual product sounds first allows one to assess a whole range of alternatives, and find out what, if anything, really makes a difference. So the process is inverted: first, you try to figure out what sounds people like their products to make, and only then do you go into the kitchens to determine whether the chefs and culinary scientists can actually create foods with the requisite sonic properties. Sometimes, those working in the kitchens will shake their heads and laugh, replying that what they are being asked to do is physically impossible. Other times, though, they will know just what is required. But whatever they say, at least everyone knows in which direction they should be heading, sonically speaking. And as a result, product innovation occurs much more rapidly.

The sound of food

Many of the food properties that we all find highly desirable—think crispy, crackly, crunchy, carbonated, creamy* and, of course, squeaky (like halloumi cheese)—depend, at least in part, on what we hear. Most of us are convinced subjectively that we “feel” the crunch of the crisp. However, this is simply not the case. Introspection, after all, often leads us astray and, based on the results of the gastrophysics research, I can assure you nowhere is this more true than in the world of flavor. (Take, for instance, the experience of carbonation. Most people, if you ask them, will swear blind that they enjoy the “feel” of the bubbles bursting or exploding in their mouths. It turns out, though, that the sensation is actually mediated largely by the sour receptors on the tongue; i.e., by the sense of taste, not by the sense of touch at all.)

Given that we don’t have touch receptors on our teeth, any feeling we get as we bite into or chew (masticate) a food is largely mediated by what is felt by the sensors located in the jaw and the rest of the mouth. The latter, removed as they are from the action, do not provide any especially precise information about the texture of a food. By contrast, the sounds that we hear when a food fractures or is crushed between our teeth generally provide a much more accurate sense of what is going on in our mouths. So it makes sense that we have come to rely on this rich array of auditory cues whenever we evaluate the textural properties of food.

Some of these sounds are conducted via the jawbones to the inner ear, while others are transmitted through the air. Our brains integrate all of these sounds with what we feel and in the case of the sonic chip this happens both immediately and automatically. And so if you change the sound, the perceived alteration in food texture that follows is experienced as originating from the mouth itself, not as a funny sound coming from your ears. This means that most of us are oblivious to just how important the sound of the crunch is to our overall enjoyment of food! And this isn’t just about the crunch: the same goes for crispy, crackly, creamy and carbonated, though the relative importance of sonic cues to our perception of texture and mouthfeel probably varies for each particular attribute. My suspicion is that what we hear is probably more relevant, and hence influential, in the case of crackly, crunchy and crispy foods than in the case of carbonation and creaminess perception. Nevertheless, research points to the conclusion that what we hear plays at least some role in delivering all of these desirable mouth sensations, and more.

Crispy and crunchy

One of the major problems associated with working in this area stems from the fact that despite all of the research that has been conducted over the years, it is still not altogether clear just how distinctive “crisp” and “crunchy” are as concepts to many food scientists, not to mention to the consumers whom they spend their life studying. Certainly, judgments of the crispness, crunchiness and hardness of food turn out to be highly correlated, thus suggesting that they are indeed very similar concepts to most of us. But matters start to get more complicated when it comes to languages other than English. Some use different terms; others simply don’t have any relevant descriptors with which to capture these textural distinctions, if such there be. The French, for example, describe the texture of lettuce as “craquante” (“crackly”) or “croquante” (“crunchy”) but not as “croustillant,” which would be the direct translation of “crispy.” Meanwhile, the Italians use just a single word, “croccante,” to describe both crisp and crunchy sensations.

Things become really confusing when it comes to Spanish. For Spanish-speakers don’t really have words for “crispy” and “crunchy” or, if they do, they certainly don’t use them. Colombians, for instance (and, I imagine, the Spanish-speakers from many other South American countries), describe lettuce in terms of its freshness (“frescura”) rather than as crispy. And when a Spanish-speaking Colombian wants to describe the texture of a dry food product, they will either borrow the English word “crispy” or else use “crocante” (the equivalent of the French word “croquante”). This confusion apparently extends to mainland Spain, for when questioned 38% of consumers there did not even know that the term for “crunchy” was “crocante.” What is more, 17% of the consumers in one study thought that “crispy” and “crunchy” meant the same thing. This is kind of bizarre when you think how important noisy foods are to our experience and enjoyment of eating. Given that we still can’t seem to agree on the definitions and differences between the various textural attributes of food, it is perhaps little wonder that research on the sound of food hasn’t progressed quite as rapidly as one might have hoped. This is unfortunate for, as top chef Mario Batali has noted: “The single word ‘crispy’ sells more food than a barrage of adjectives describing the ingredients or cooking techniques.”

“Why is a soggy potato chip unappetizing?” This was the title of a commentary in a top science journal called (you guessed it) Science a few years ago. The nutrient content doesn’t change as a crisp becomes stale but, for whatever reason, none of us seems to like the soggy variant. And yet, no one was, I suspect, born liking noisy food. It is on this point that I have to disagree with Mario Batali when he says: “There is something innately appealing about crispy food.” No, there isn’t. Indeed, most of what we think of as innate is, in fact, learned. In other words, we all learn to like specific food sensory cues, in large part because of what they signal to our brains about what we are consuming (and what physiological rewards are to come). Crisp and crunchy—well, they signal fresh, new and maybe seasonal too.

Perhaps the more fundamental question that we should concern ourselves with is why exactly crispy, crunchy and crackly have come to constitute such universally desirable food attributes. These sounds don’t directly signal the nutritional properties of a food—or do they? Let’s examine crunchiness, which undeniably provides a pretty good (i.e., reliable) cue to freshness in many fruits and vegetables. This information would have been important for our ancestors, since fresher foods preserve more of their nutrient content and hence are better to eat.

Cooking induces the Maillard reaction, the non-enzymic browning that results from strong heat being applied to nitrogen- and carbohydrate-containing compounds. In his book The Omnivorous Mind, John S. Allen points to the fact that cooking by fire simultaneously makes foods both more nutritious (or, more accurately, easier to digest) and crispier. Think, for instance, of the delicious crustiness of freshly baked bread. Hence this may be why, in evolutionary terms, the sounds of crispy, crackly, crusty and crunchy are so important. Part of the answer to the question of why soggy foods are so unappealing may also relate to the latest research showing that as the crunchiness of a food increases, so too does its perceived flavor. No surprise then that we all want more crunch. In fact, consumers the world over demand it!

Our strong attraction to fat may also be relevant here. The latter, after all, is a highly nutritive substance, perhaps explaining why we have taste receptors in the oral cavity sensitive to the presence of fatty acids. However, it can still be a challenge for our brains to detect fat directly in food and drink. Why so? Well, often its presence is masked by other tastants like sweet and salt. While cream, oil, butter and cheese are all associated with a distinctively pleasing and desirable mouthfeel, my suspicion, at least as far as dry snack foods are concerned, is that our brains may have learned, as a result of prior experience (i.e., exposure), that these sonic cues are suggestive of the presence of fat. That is, the louder the crunch, crackle, etc., the higher the fat content of the food we are biting into is likely to be. So we all come to enjoy those foods that make more noise because they probably have more of the rewarding stuff in them than other, quieter foods. Now you know why you find it so hard to resist the sound of crunch!

How do you feel about eating insects?

I’m sure I know the answer to that question without you having to say a word. But, knowing what we now know about sound, we should all find the idea rather more desirable than, in fact, we do. Many insects are, after all, pretty crunchy, at least those with a hard carapace or exoskeleton (see Figure 4.2). What’s more, they provide an excellent source of protein and fat. It would be good for the planet, too, if we all ate more of these little critters (and less red meat). And yet, no matter what you or I say, most Western consumers are yet to be convinced. Marketing insects so that people—by which I mean us in the West—find them desirable is, I feel sure, going to be one of the ultimate challenges for gastrophysics in the coming years. How exactly do we take everything we know about the mind of the consumer and make this currently most undesirable food source truly delicious? Or, at the very least, make sure that insect matter constitutes a larger proportion of our diets. Playing on the sound of crunch might offer one way in to the popularization of entomophagy (that’s the fancy term for eating insects).

Figure 4.2. A crunchy and protein-rich snack. Deep-fried crickets should tick all the right boxes as a highly desirable and moreish treat.

So what gastrophysics insights might help here? Well, one option is simply to surreptitiously increase the amount of insect matter that people already eat. (If you are a peanut butter fan, you might want to skip the rest of this paragraph!) I bet you didn’t know that there can be as many as 100 insect parts, for example, in every jar of peanut butter before the producer has to declare this on the label. The same must presumably also be true for jam (due to the difficulty of keeping tiny creatures out), and who knows what else is in your ground coffee. So why not slowly increase that number (while at the same time reducing other ingredients that are in short supply, or are unhealthy)? I bet that in the future insect-based matter will become a more substantial part of our diets without the consumer ever noticing. This is like the health-by-stealth strategy that worked so well for the cereal companies when they decreased the amount of salt in their breakfast cereals. They reduced the salt content by as much as 25% by doing it gradually. Consequently, each successive reduction was essentially imperceptible to the consumer; and over the long term, levels of unhealthy ingredients have dropped substantially.

Alternatively, we might work on distinguishing between more and less disgusting critters. For, if you think about it, we already eat lots of bee-based products, everything from honey (sometimes mistakenly called “bee vomit”) through to royal jelly and propolis. So eating bee brood (i.e., baby bee) ice cream shouldn’t be too much of a leap, should it? We don’t seem to find ladybirds so disgusting either—certainly if one lands in my beer, I will happily flick it out and keep on drinking.

It may be, though, that the sensory strategy that works best in the long term is one that builds on the sound of crunch—something, after all, that we know most consumers really like. All the gastrophysicists have to figure out now is which insects, and which method of preparation, would make the loudest crunch of all. Then away we all go, to a crispier, crunchier and more sustainable future.

Why do crisps come in such noisy packets?

As well as the sounds of preparation and the noises associated with our consumption of food and drink, the sounds of product packaging also have a pronounced impact on our tasting experiences. Do you think that it is an accident that crisps come in such noisy packets? Of course it isn’t! From the very beginning, marketers intuited that it would make sense to have the sound of the packaging be congruent with the sensory properties of the contents. This is as true today as it was back in the 1920s when crisps were first packaged for fresh, portion-controlled delivery direct to the consumer. Even Pringles, whose packets typically make less noise than most other snacks, have done something to enhance the sound of their foil seal. You don’t have to take my word for it—try running your fingers over it next time you come across a tube and just listen to the difference.

But just how much influence does the sound of the packaging really have on our judgments of the product within? Well, a few years ago, we tackled this very question. Together with Oxford undergraduate Amanda Wong, we conducted a study showing that the louder the rattling packaging sound that people heard as they ate, the crunchier-seeming were the crisps they had been asked to rate. While the effects were nothing like as dramatic as those we saw when we modified the sound of the crunch itself, they were still significant. In other words, in terms of perception, our brains appear to have a remarkably hard time distinguishing the product from the packaging.

Frito-Lay may have taken these findings a little too seriously when they came out with their all-new biodegradable packaging for SunChips. This, let me tell you, is probably the loudest packaging ever created (see Figure 4.3). When my colleague Barb Stuckey sent me a couple of packs from California, we got the sound meter out to determine in the lab how much noise they gave off when gently agitated in the hands. The answer: in excess of 100 dB! To put that number into perspective, this is the background noise level that you will find in the very loudest of restaurants. Moreover, it is the sort of noise level that, if one is exposed to it for long periods of time, can lead to permanent hearing damage!

The packaging was so loud that many consumers wrote in to complain. It was so loud that the company was forced to offer ear plugs to try and quell the growing consumer backlash. The idea, I suppose, was that you would buy a packet of SunChips, get them home, then insert the ear plugs and enjoy your snack in peace. You’d have to feel sorry for anyone who was sitting nearby. Even worse if they suffered from misophonia (sufferers find the sound of other people masticating unbearable). Eventually, of course, this damage-limitation exercise failed miserably, and the company withdrew their sonically supercharged packaging from the shelves altogether, never, I suspect, to be seen nor, more importantly, heard again.

Figure 4.3. Sonic warfare? Quite possibly the noisiest packaging on earth, creating in excess of 100 dB of rattling noise when the packaging is gently agitated in the hands. Who thought that was a good idea?

You can almost hear the marketing executives rubbing their hands together with glee, though, at the ingeniousness of their original idea. We had shown at the Crossmodal Research Laboratory that noisy packaging helps bring out the crunch of the crisp, so surely selling your noisy product in even noisier packaging ought to make your product seem crunchier still. (Assuming, that is, that people eat direct from the pack, rather than pouring the contents out into a bowl or plate. This, though, is a reasonable assumption, given claims that a third of all food is eaten direct from the packaging; if anything, I would imagine that this figure is likely to be much higher in the case of crisps.) The noisy packaging also had the advantage of being extremely effective at capturing the attention of consumers. For as soon as anyone picked a pack off the shelf in the supermarket, you could guarantee that everyone else in the aisle would be looking around to see what the hell was going on. While I doubt there will be anything as noisy ever again, you may be sure that many other companies are thinking about or even actually subtly modifying the sounds that their packaging makes. But the real moral of the SunChips story is “everything in moderation.” Just because more sound is good, that doesn’t mean that even more sound will necessarily be better!

“Snap, crackle and pop”

Product sounds can help set our expectations regarding the product category, or even the specific brand. Some years ago, Kellogg’s even tried to patent their crunch. They wanted to trademark the distinctive sound that their breakfast cereals made when the milk was added. They hired a Danish music lab to create “a highly distinctive crunch uniquely designed for Kellogg’s, with only one very important difference from traditional music in commercials. The particular sound and feel of the crunch was identifiably Kellogg’s, and anyone who happened to help himself to some cornflakes from a glass bowl at a breakfast buffet would be able to recognize those anonymous cornflakes as Kellogg’s.”

Packaging sounds can help set our expectations too. According to Snapple (the beverage company owned by Dr. Pepper Snapple Group, Inc.), the distinctive (or signature) sound that the consumer hears on unscrewing the cap from an unopened bottle provides a cue to freshness. “The company calls it the ‘Snapple Pop’ and says it builds anticipation and offers a sense of security, because the consumer knows the drink hasn’t been opened before or tampered with. Snapple was so confident about the pop’s safety message that in 2009 it eliminated the plastic wrapping used to encircle the lid. It saved on packaging costs and eliminated an estimated 180 million linear feet of plastic waste, the company says. ‘We were a lot more comfortable making that decision because we knew there was this iconic pop,’ says Andrew Springate, senior vice-president of marketing.”

Given how much money the food and beverage companies spend on developing and protecting their visual identity, it is surprising how few of them seem to give much thought to their sonic identity. Interestingly, though, as far as I am aware, Snapple hasn’t protected the “Snapple Pop.” This may be because it has proved hard to trademark specific product sounds (as Harley-Davidson found to their cost when they tried to protect the rich, low-pitched “potato-potato-potato” sound of their motorcycle exhausts).

Many advertisers have picked up on the potential of sound—not much escapes the ears of marketers. Often they attempt to draw attention to the noises that products make when opened, poured and/or consumed on screen. The JWT ad agency, for example, worked on a campaign in Brazil to emphasize the sound that Coca-Cola makes when poured into an ice-filled glass. Or think of the loud crack you hear on the Magnum ice cream ads, or the iconic sound of someone running their fingers along the foil seal of the old-fashioned Kit-Kat.* What other distinctive food packaging sounds can you think of?

What does your food sound like at home?

All right, I hear you say, I can see why big companies or chefs might be interested in sound or in sonically mediated food textures, but how does this affect us mere mortals? Well, the latest findings from gastrophysics highlighting the importance of sound also provide insights that you can take advantage of at home. For instance, the next time you throw a dinner party, be sure to ask yourself where the sonic interest lies in the dishes you serve. If it isn’t crunchy, crackly, crispy or creamy, are you stimulating your guests’ senses as effectively as you might? The solution can be quite simple: just sprinkling some toasted seeds over your salad, or adding some crispy croutons to your soups at the last minute. This presumably explains the ubiquitous presence of the gherkin and Batavia lettuce (also known as French crisp lettuce) in your burger bun too—they add a sonic element that makes you enjoy the experience of eating the burger that much more.

Those of you who are a little more adventurous might want to try sprinkling some popping candy into your chocolate mousse, or even into the potato topping of your shepherd’s pie. These are both approaches that top chefs have incorporated into their dishes over the years. And if you want to make the sonic surprise all the more memorable, “hide” it. Your guests will be taken aback when, several mouthfuls into that mostly silent chocolate mousse, say, they suddenly experience an explosion of sound in their mouths. Something that they won’t soon forget, I can assure you! This is a good thing, as we will see in the “Meal Remembered” chapter.

Have you ever wondered why the pairing of Melba toast with pâté works so well? Is this not a classic example of taking a great-tasting but silent food (that’s the pâté), and adding to it a burst of noise (when biting into the crisp toast)? Sure, there is texture contrast here (and that is important too). But fundamentally, is it not really about injecting some sonic interest into the dish? More often than not, in fact, our perception of flavor in a meal is enhanced when sound is introduced. Indeed, as we saw earlier, some of the most interesting recent research has shown that as the crunchiness of a food increases, so too does its flavor. In The Omnivorous Mind, John S. Allen also suggests that loud foods might be more resistant to habituation than silent ones. This, he believes, might be part of their universal appeal. So there you have it. Whatever you do, make sure you add some sonic excitement to mealtimes. Better just first check that there aren’t any misophones at the table . . .

If sound is as important to the perception of crunchiness and crispness as we think, then maybe there is a solution here if you find that you only have stale crisps in the cupboard next time you throw a party. According to research, your guests probably won’t realize just as long as you turn the background music up loud enough to mask the missing sound of the crunch. For as soon as you introduce some loud background noise, your guests’ brains will fill in the missing sound of the crunch that they can no longer hear properly. Be warned, though: all that loud noise is also likely to impair your guests’ ability to determine how alcoholic your punch is. And if any of them should be impertinent enough to ask you why the music is so loud, just tell them that all the best chefs do it nowadays (about which more below).

“Pardon?” Taking the din out of dinnertime

When was the last time you went out to eat, only to find it difficult to hear the conversation of your companions? My guess is that it probably wasn’t long ago. The problem of overly loud restaurants (not to mention bars) has become far more widespread in recent years. Public spaces can be so noisy that many of us can no longer hear ourselves think, never mind get our orders across. Noise is currently the second most common complaint among restaurant-goers, behind poor service. In fact, over the last decade or two, many restaurants have become so loud that some critics now report on the noise levels alongside the quality of the food in the venues they judge.

The blame for this growing cacophony has been laid, in part, at the doors of the New York chefs, famous for listening to very loud music while preparing for service. No one knows quite when it started, but at some point one of them had the “bright” idea that maybe the diners would like it as well. Bad move! For as one journalist astutely notes: “No matter how elegant the food at a restaurant, the music that plays as it’s prepared is likely to be less refined. No one is listening to Vivaldi as he buffs baby vegetables and dismembers ducks.” Charles Michel, the former chef-in-residence at the lab, told me that when he worked at the Louis XV restaurant in Monaco’s Hôtel de Paris, the chef de cuisine, Frank Cerutti, would put on some heavy metal during the mise en place in order to make the kitchen staff go faster!

Part of the responsibility must lie with those designers who have insisted on the restaurants they advise ditching their soft furnishings, leaving spaces filled with hard reflective surfaces. The new Nordic look—you know, all that bare wood, and with carpets, upholstered chairs and tablecloths removed—has a lot to answer for, sonically speaking! There is nothing left to absorb all the noise. That said, though, the chefs might not be entirely blameless. After all, part of the reason for removing the tablecloths in Grant Achatz’s Michelin-starred restaurant Alinea, in Chicago, was to give the dishes a little more sonic interest when first placed on the table.

The backlash against restaurants and bars that are overly noisy has been growing steadily. According to a recent press report: “[A] group of Michelin-starred chefs have started a campaign to reduce noise levels in Spanish restaurants amid concerns that it is spoiling the gastronomic experience for some guests.” Others have gone further. Ramón Freixa, chef at the two-Michelin-starred Hotel Único in Madrid had this to say recently: “Gastronomy is a sensual experience and noise prejudices this pleasure. A good conversation with the people you are dining with should be the only sound in a restaurant.” So how is the din to be taken out of dinnertime? While a successful restaurant full of customers can do without music, it is obviously going to be a much harder trick to pull off in a lightly populated venue. Furthermore, it is also worth remembering here that background music serves to insulate one table’s conversation from the prying ears of those seated nearby. A better aim, then, might be to set the volume level so that the music is “very present but it’s never overpowering.”

A number of chefs and culinary artists have spotted a gap in the market and have been arranging silent dining events. If you eat in silence, then you can really concentrate on the food (and no, texting isn’t allowed either, before you ask). This should enhance the sensory pleasure of the experience. Much the same logic underpins all those dine-in-the-dark restaurants out there. Such mindful dining might even lead to reduced consumption. That said, these events have not been a commercial success, I suspect because while this strategy can help to build anticipation by emphasizing the sounds of preparation coming from the kitchen (at least if managed appropriately), insisting on silence also precludes the main activity when eating and drinking, namely the social aspect of communicating with those who you are with.

Across a number of studies we, and a growing number of other researchers, have been able to demonstrate that what we listen to (and how much we like what we hear) influences the taste, texture and aroma of a diverse range of foods. People’s hedonic ratings (i.e., how much they like the food or drink) are also affected. Often—but, interestingly, not always—the more we like the music, the more we enjoy the taste of the food or drink consumed while listening to that music. For instance, one recent study revealed that liked music brought out sweetness in gelati, whereas disliked music tended to bring out bitterness in a group of trained panelists. While some have wanted to dismiss such results as little more than a party trick, I would argue that this research may actually have some profound implications for the way in which we think about the senses and food. Furthermore, such results will, I believe, affect the future design of multisensory tasting experiences, no matter where you may happen to find yourself. In fact, we will come across a number of examples in the chapters that follow. So my prediction is that you are going to hear a lot more about sonic seasoning in the years to come.

Sonically enhanced food and drink

When it comes to consumption, many of the food attributes that we find most pleasurable—think here of the crispy, crunchy, crackly, creamy and carbonated—are all influenced, to a greater or lesser extent, by the sounds we hear during consumption. While this is undoubtedly important for younger consumers, in the future, I suspect, boosting the sonic interest of one’s dishes is going to become even more important for the rapidly growing aging population. After all, the number of us living past seventy is steadily increasing, and this is the age at which one starts to see some really dramatic decline in the ability to taste and smell (much though my octogenarian parents deny it!). Now, for any of you out there feeling relieved that this doesn’t apply to you, I’m afraid that I’ve got some bad news.

According to the sensory scientists, if you are out of your teens, the chances are that the decline has already started. Not feeling quite so smug? I didn’t think so. Research clearly shows that the majority of older adults are pretty much anosmic: i.e., they can no longer smell anything much at all. Unfortunately, there is currently absolutely nothing that can be done to bring back the sense of taste or smell once they have begun their inevitable decline (unlike the boost we can give failing vision or hearing with spectacles or hearing aids). But one thing that can be done is to make sure that dishes served to the elderly have lots of crunch and crackle—more sonic interest, in other words. This should help to stimulate the mind and palate of whoever is eating.

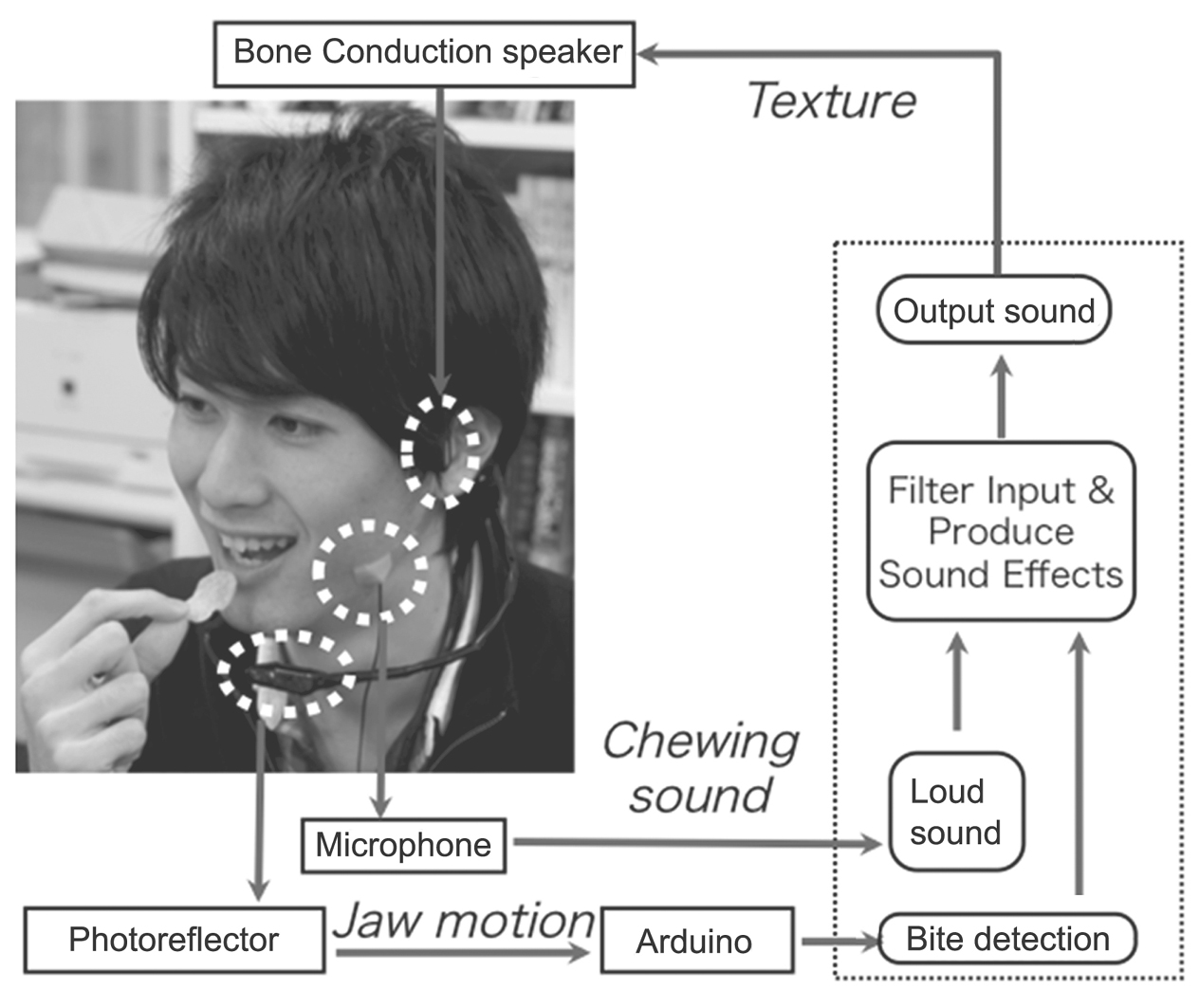

Figure 4.4. The playful “Mouth Jockey” detects the user’s jaw movements and then plays back a specific pre-recorded sound.

So what have younger people, whose taste buds and, more importantly, noses are still in good working order, got to look forward to? Researchers in Japan have developed a playful headset called the “Mouth Jockey” (see Figure 4.4), which detects the user’s jaw movements and plays back pre-recorded sounds while the user eats. Just imagine hearing the sound of screaming as you bite into a gummy bear, say. Others have been working on augmented straws that can recreate the sounds and feeling associated with sucking liquidized food through a straw: place the straw over a mat showing a picture of the desired food and then suck. It is amazing how realistic and how much fun the experience can be.

The EverCrisp sonic app allowed you to “freshen up” your stale crisps by using your mobile device to add a little more crunch. While it is tempting to imagine that technology will come to play an increasingly important role in augmenting our experience of food in the years to come (see the “Digital Dining” chapter), I believe that there will also be a crucial role for design. I want to leave you, therefore, with the Krug Shell (see Figure 4.5) as an example of what is possible here. This Bernardaud Limoges porcelain listening device, which was released as a limited edition offering back in 2014, sits snugly on top of a custom Riedel “Joseph” champagne glass. If you can somehow get your hands on one, I’d encourage you to try it. You will hear how the sounds of all those bubbles popping in your glass have been pleasantly amplified. Then sit back and contemplate whether you are really happy to let sound remain “the forgotten flavor sense.”

Figure 4.5. The Krug shell, designed by French artist Ionna Vautrin to amplify the sound of the bubbles popping in a glass of champagne.