6. The Atmospheric Meal

When we imagine an eating experience, we can’t ignore the setting. If you are far from home, in some foreign city, deciding where to eat, don’t you always end up gravitating toward the restaurant that has a buzz, a vibe, in other words, the one that has “atmosphere”? And don’t we all mostly stay away from those places where there aren’t any diners—you know, restaurants that look stone dead—no matter how highly they come recommended?

Can the atmosphere in a restaurant determine how much we eat, not to mention how much we spend? Many restaurateurs certainly believe so. As the owner of Pier Four in Boston said, back in 1965 when it was one of North America’s most successful restaurants: “If it weren’t for the atmosphere, I couldn’t do nearly the business I do.” But beyond its effect on table turnover, not to mention maximizing the bottom line, can you really enhance the perceived taste and/or enjoyment of a meal just by picking out the right sort of background music? Does the same food actually taste different when the atmosphere, or environment, in which it is served changes? As I will show you in this chapter, emerging gastrophysics research shows that the answer to these questions is very often yes.

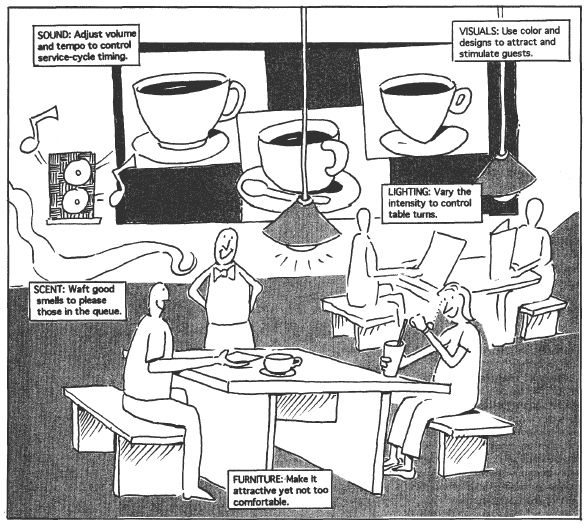

Environmental attributes, from the music through to the lighting, and from the ambient scent through to the feel of the chair you are sitting on, can—and in many cases do—influence the dining experience. Marketers have long been aware of the profound influence of the environment. The famous North American marketer Philip Kotler, for instance, in his seminal early paper on “atmospherics,” emphasized how a key part of the total product offering is the atmosphere in which a product or service is presented, which is itself multisensory. He drew a distinction between the tangible product and the total product. He is, I think, worth quoting at length given how influential this work has been: “The tangible product—a pair of shoes, a refrigerator, a haircut, or a meal—is only a small part of the total consumption package. Buyers respond to the total product. [. . .] One of the more significant features of the total product is the place where it is bought or consumed. In some cases, the place, more specifically, the atmosphere of the place, is more influential than the product itself in the purchase decision. In some cases, the atmosphere is the primary product.”

To date, the majority of the research on atmospherics has tended to focus on music—the easiest aspect of the environment to change. So, to begin with, let’s take a look at the evidence concerning the effect of background music on our dining behavior.

Moving to the beat

Do you think that you would eat and drink more rapidly if the tempo or loudness of the music in a restaurant increased? Would you end up spending more if they were to play classical rather than top-forty music, say? And would you be more likely to choose something French if accordion music was playing in the background? Sounds unlikely, right? Yet in one of the most impressive demonstrations of background music’s impact on consumer purchasing behavior, this is exactly what was found. In particular, researchers alternated the type of music in the wine section of a British supermarket. When French music was played, the majority of people bought French wine; however, when distinctively German (Bierkeller) music was played instead, the majority of wines sold were German. The numbers have to be seen to be believed (see Figure 6.1).

Most people, when told about such results, are convinced that they wouldn’t be so easily influenced. So too, in fact, were the customers who were questioned on leaving the tills in the study itself, the majority of whom resolutely denied that the music playing in the background had swayed their purchasing decisions that day. They confidently asserted that they had always intended to buy French wine, as the accordion music played in the background. However, the sales figures tell a very different story. Given results like these, you can probably better understand why gastrophysicists are often so skeptical of people’s subjective reports. Better to look at what people do, rather than merely relying on what they say.

Figure 6.1. Number (and percentage in parentheses) of bottles of French versus German wine sold as a function of the background music in one of the most oft-cited marketing studies on the impact of ambient music on people’s behavior.

Do you think that your food preferences would be affected by a restaurant deciding to change its decor? Well, one study that went some way toward answering this question was conducted at the Grill Room at Bournemouth University, in the U.K., back in the early 1990s. Researchers wanted to know whether they could alter the perceived ethnicity of a range of Italian dishes without changing the food offering. To that end, a selection of Italian and British foods was offered up over four days. On the first two days, the restaurant was decorated as normal (e.g., with white tablecloths and the walls and ceiling unadorned). For the other two days, the restaurant was given an Italian feel: Italian flags and posters were mounted on the walls and ceiling, the tables were covered with red and white checkered tablecloths. Oh, and a wine bottle was placed on each table for good measure.

The diners (138 of them, to be precise) were invited to complete a questionnaire once they had finished their meal. They were asked how ethnic their meal had been, as well as how acceptable they found the food overall. Giving the restaurant an Italian theme resulted in diners choosing more pasta and Italian desserts such as ice cream and zabaglione, and significantly fewer fish dishes. Adding an Italian feel also resulted in the pasta items being rated as more authentic. The perceived ethnicity of the meal as a whole went up too, with 76% of the diners describing the meal as Italian, as compared to only 37% in the baseline condition. Such results illustrate how what people think about a meal can be influenced by changing nothing more than the visual attributes of the environment in which that dish happens to be served. And given what we have already seen, had Italian music been played too, who knows how much more pronounced the multisensory atmospheric effects would have been?

So at home, you could perhaps make your pizza and pasta taste more authentic by playing a bit of Italian opera. The film director Francis Ford Coppola, for one, insisted on “musical accompaniments matched to menus—accordion players for an Italian pranzo, mariachi for Mexican comida” whenever he was filming.

The question remains, what might work best, practically speaking, in terms of music to accompany your takeaway pizza? Well, you’ll be glad to hear that here at the Crossmodal Research Laboratory we have done the relevant study in order to determine just that (even if Italian music might make Italian food seem more authentic, it still might not give rise to the best experience for the diner). In a recent project conducted on behalf of Just Eat (an online food-ordering company, like Seamless in the U.S.), we asked more than 700 consumers which of 20 musical tracks worked best with the 5 most common types of takeaway food in the U.K.: Italian, Indian, Thai, Chinese and sushi. The music spanned several genres, from R’n’B and hip-hop, pop and rock, through to classical and jazz. Pavarotti’s “Nessun Dorma” came out as the top match for takeaway Italian food. Across the board, Nina Simone’s “Feeling Good” and Frank Sinatra’s “One for My Baby” were always ranked in the top three tracks, regardless of the type of takeaway that our participants were evaluating. So they too would seem to be a safe bet for anyone without a compendious music collection. But the really big surprise was that Justin Bieber’s “Baby” came pretty much bottom. So that one is a big no-no—you have been warned. (Sorry, all you Beliebers out there . . . but you can’t argue with the data!) As to why the results turned out this way, well, that is a question that we are still working to answer.

Playing classical music in the background tends to result in people splashing out more. This turns out to be true no matter whether one is looking at diners’ willingness to pay for the food served in a student cafeteria or customers’ actual spending behavior in a restaurant setting. In fact, a 10% increase in the average bill is not unheard of. For instance, in one study conducted by Professor Adrian North, at Softley’s restaurant in Market Bosworth, Leicestershire, the diners spent £2 a head more, on average, when classical music was playing in the background rather than pop. In another study, the customers in a wine store were shown to spend more when classical music rather than top-forty music was played.

Background music can impact how pleasant we rate the food itself. No prize for guessing that the more discomfiting the music, the less time people spend in a given environment, while the more they like the music, the longer they stay. And, generally speaking, the more you like the music, or the environment, the more you like the food and drink. That said, I always suggest to clients that they should conduct their own research in order to know what kind of musical backdrop will work best for them. There may well be some significant cross-cultural differences here in terms of the appropriateness of music (and/or conversation) at mealtimes too. In Korea and Japan, for instance, it is far more common to eat a restaurant meal in silence without people talking much to one another, and with no music in the background.

That said, it is important to bear in mind the congruency between the restaurant concept, the clientele and the type of music that is played. It is hard to believe that classical music would necessarily be the right choice in one of those grungy burger bars that are popping up all over the place these days. It just wouldn’t seem appropriate, would it? But for a high-end hotel restaurant, where the mark-up on the French wine is much higher than for any of the other stuff that they have in the cellars, the implications are clear. What we can infer here is that classical music is more likely to prime notions of class, and/or that those who are drawn to classical music may, on average, be a little more affluent.

Next, let’s take a look at tempo, i.e., the number of beats per minute (bpm), and loudness. Is the speed at which you eat or drink influenced by the speed of the music playing in the background? By now, I am sure you can guess what the answer to this question will be. And indeed, playing faster music has been shown, across a number of studies, to result in people eating and drinking more rapidly. In what is perhaps the classic study in this area, this time conducted by R. E. Milliman, a North American professor of marketing, back in 1986, the tempo of the music playing in a medium-sized restaurant was manipulated. The 1,400 North American diners whose behavior was assessed ate much more quickly when fast (as compared to slow) instrumental music was played. When slow music was played, diners spent more than 10 minutes longer eating, bringing the total duration of their restaurant stay up to almost an hour. Although the musical tempo had no effect on how much money people spent on their food, there was a marked difference on the final bar tab, with those exposed to the slow music spending around a third more! Slowing the music down increased the restaurant’s gross margin by almost 15%, no doubt a sensible idea at quiet times. However, when the customers are queuing out of the door, the restaurateur might be better off playing some fast-paced music instead.

But would a restaurant chain really go to such lengths to control the flow of customers? Absolutely! Just listen to Chris Golub, the man responsible for selecting the music that plays in all 1,500 Chipotle restaurants in the U.S.: “The lunch and dinner rush have songs with higher bpms because they need to keep the customers moving.” In fact, Golub is often to be found sitting in his local New York branch of Chipotle, observing people’s behavior in response to the different music that he is thinking of adding to the playlist. Then, depending on the customers’ responses, he will fine-tune it both for tempo and style before it is beamed out to branches across the land. All that is missing here is the statistical analysis and this would be fully-fledged gastrophysics research!

Ultimately, of course, restaurateurs and bar managers are primarily interested in increasing their profits. The Hard Rock Café chain, for instance, plays loud music in its venues because of the positive effect on sales. Just take the following, from a piece that appeared in The New York Times: “[T]he Hard Rock Café had the practice down to a science, ever since its founders realized that by playing loud, fast music, patrons talked less, consumed more and left quickly, a technique documented in the International Directory of Company Histories.” And according to another report: “When music in a bar gets 22 percent louder, patrons drink 26 percent faster.” This shines a whole new light on why so many restaurants and bars are getting louder than ever before. Put simply, it makes us spend more!

That said, much of the underpinning research was conducted years ago, in a different time and place; the results may no longer apply. My recommendation to the restaurateur is just to be aware of the importance of the atmosphere to the food offering you provide. This should at the very least help you to avoid the situation whereby the chef who obviously cares passionately about their food allows the front-of-house manager to put their iPod on random shuffle. You know the sort of thing: you suddenly find yourself listening to Frank Sinatra singing “Jingle Bells” in the middle of July when eating in a Thai restaurant, say! This really shouldn’t happen. But I think we all know that it does, and more often than it ought to. If you have the opportunity to experiment, why not try French music this week and American Rock next, or classical music today and the top-forty tomorrow, and see for yourself the impact on what people say (or, more importantly, on sales). Gastrophysics research provides a number of suggestions as to what might happen, but you will have to check for yourself to be sure of getting the effect you want. Broadly speaking, though, when the atmosphere matches (or is congruent with) the food offering, people will tend to enjoy the experience more.

Do you care about being comfortable?

Have you ever wondered why most trendy coffee shops have such hard and uncomfortable seating? Well, put simply, they just don’t want you to linger. I know of a number of baristas who deliberately chose hard, uncomfortable furniture in order to discourage their customers from loitering and hogging the tables all day long. You don’t need a gastrophysicist to tell you that the less comfortable the chair, the shorter your stay will be. McDonald’s has been doing this for years; as one commentator put it: “The rule written into the design of the seats [in McDonald’s] is that 10 minutes is the appropriate length of one’s stay before they become uncomfortable.” At the high end, though, where the duration of the customer’s stay isn’t an issue, restaurants are increasingly thinking about how to augment the feel of the space in which their food is served. A few innovative chefs, such as Joshua Skenes, chef-owner of Saison in San Francisco, have started to play with giving their restaurants a distinctive feel. According to the chef: “You need great food, great service, great wine, great comfort. And comfort means everything. It means the materials you touch, the plates, the whole idea that the silverware was the right weight. We put throws on the back of the chairs.” Take a look at Figure 6.2; it seems Noma in Copenhagen are doing much the same thing.

Would you rather sit at a round or a square table? Generally speaking, people prefer round (or curvilinear) to angular forms, a preference that extends all the way from everyday objects through to architectural spaces and even furniture. Some evolutionary psychologists put this seemingly ubiquitous preference down to angular forms being associated with danger (think sharp and dangerous weapons). Of course, due to practical constraints, the majority of traditional restaurant floor plans are angular. But a square space can be the frame for much rounder forms, in the decoration or the furniture.

Figure 6.2. A chair with texture at Noma in Copenhagen.

In one recent study, a group of North American university students was shown pictures of interior environments containing either angular or rounded furniture. The results highlighted a preference for rounder furniture, with the latter tending to elicit greater feelings of pleasure as well. Interestingly, in this case, the participants reported a greater desire to approach the curvilinear rather than the rectilinear furniture. As one of the participants said: “[R]ounded furniture seems to give off that calming feeling.” Round tables can be used to help make the interior of a restaurant appear more welcoming. But they also reduce capacity—presumably why many restaurant consultants recommend a mixture of round and angular tables, aiming for a balance between approachability and profitability.

How would you like to dine in a white cube?

There are some traditional establishments where no attempt has been made to augment the atmosphere whatsoever: Just think of those temples to haute cuisine with their unadorned white walls, diners sitting before a starched white tablecloth (or, as is currently fashionable, just a starched napkin), eating in hushed and respectful silence. No one could claim that such venues were trying to distract their diners from the food, right? The idea of releasing ambient fragrance or changing the temperature of the space to match the dishes being served would, one imagines, be complete anathema to such traditional restaurateurs. I guess that there will always be a place for such austere dining rooms. But my sense is that it is hard to make this kind of approach seem contemporary or exciting, at least in the current climate. More often than not, such venues are being replaced (in the San Pellegrino listing of the world’s fifty best restaurants, say) by the more experiential dining concepts.

What is more, bear in mind that by removing atmospheric cues one is still making a statement. Here, I am reminded of a quote from one commentator: “The modern restaurant is an experience in codes. The architecture, the foods served, and even the customers are codes built up to the total consumable image. Restaurants then do not just serve food. They serve an experience.” So while the decor may be minimalist, the atmosphere is very definitely never “neutral.” Make no mistake, the dishes served in the “white cube” environment will be rated differently by diners than in any other environment that one might care to choose. Based on the evidence, the food would probably be rated as better in quality and more expensive, though perhaps less memorable. The key point is that there is always an atmosphere wherever food is served and consumed.

The same also goes for those healthy, natural, organic stores and restaurants, the places with the baskets of fresh produce on display as you walk in (many of Jamie Oliver’s restaurants fall into this category). Make no mistake about it, this kind of atmosphere is itself priming notions of healthy and natural in the mind of the diner. It may look casual, but it most certainly isn’t—the creation of the display is itself artifice. Often, a great deal of thought has gone into constructing that “natural” environment to be just so. That is part of the conceit; in fact, I bet it affects the experience just as much as in other restaurants where the atmosphere changes on a course-by-course basis. They are still creating an impression, an expectation that will color the whole encounter between the diner and their food and drink.

Over the years, some restaurants have really gone overboard in terms of delivering a multisensory atmosphere. One of the most famous early examples here is The Tonga Room & Hurricane Bar, which opened down in the basement of the Fairmont hotel in San Francisco back in 1945. I still remember visiting as a young graduate student, long before my current interest in multisensory dining had taken root. A spectacular tropical thunderstorm, with simulated thunder and lightning, would unfold every thirty minutes or so during opening hours. Good idea though this was, presenting the same old sound and light show for so many years had taken its toll on the place—it was looking a little tired. Furthermore, it is easy to imagine how the customers might well habituate to the repeating multisensory scene that unfolds.

A little over five decades after The Tonga Room first opened its doors to the public, and on the other side of the pond, as it were, one finds The Rainforest Café. This well-known London restaurant also delivers an experience that tries to stimulate all of the customers’ senses. Every half an hour or so, the restaurant goes dark while the guests are “treated” to all the rumbling and flashing of a thunderstorm in the tropics. While The Tonga Room targets a more mature clientele, the latter venue obviously has its sights set on a much younger market (or rather, on the pockets of those who have been charged with looking after them). As the self-styled engineers of the experience economy (see “The Experiential Meal”), B. J. Pine, II, and J. H. Gilmore, say: “The mist at the Rainforest Café appeals serially to all five senses. It is first apparent as a sound: Sss-sss-zzz. Then you see the mist rising from the rocks and feel it soft and cool against your skin. Finally, you smell its tropical essence, and you taste (or imagine that you do) its freshness. What you can’t be is unaffected by the mist.”

No matter whether the grown-ups like it or not, there can be no doubting how incredibly successful the experience has been among the target audience, namely children. For a few years, my nieces were huge fans, though I suspect that they have rather grown out of it now. And what is absolutely clear is just how successful the venture has been, commercially speaking. In other words, atmospherics sells, or at least it does when done well.

There has sometimes been, it has to be said, a lingering suspicion that restaurateurs are interested in the atmosphere only insofar as it differentiates them from the competition and increases their bottom line. Of course, it is all too easy to get a little sniffy about the grubby financial side of things, but who isn’t ultimately interested in at least breaking even? As the influential British chef Marco Pierre White once put it: “Any chef who says he does it for love is a liar. At the end of the day it’s all about money. I never thought I would ever think like that but I do now. I don’t enjoy it. I don’t enjoy having to kill myself six days a week to pay the bank . . . If you’ve got no money you can’t do anything; you’re a prisoner of society. At the end of the day it’s just another job. It’s all sweat and toil and dirt: it’s misery.”

One could also mention the popular dine-in-the-dark restaurants here (e.g., Dark Restaurant Nocti Vagus in Berlin)—they clearly fit into the atmospherics framework, with a sensory input removed, rather than added. Nevertheless, going to one of these restaurants is very definitely an experience, but not necessarily one that is centered on great-tasting food.

To summarize, then, the atmosphere affects our food behaviors in a number of ways: everything from influencing where and what we “choose” to eat, through how long we stay, not to mention what we think of the overall experience (see Figure 6.3). But it is worth noting that we haven’t so far addressed the more fundamental question of whether changing the environment really does modify what people perceive on the plate or in their glass. This is the kind of question that is of most interest to the gastrophysicist.

Figure 6.3. All of the senses play a role in controlling our behavior while drinking and dining. The intelligent restaurateur knows how to work with the senses to create the right environment. The scientific approach to multisensory atmosphere design has led to a number of restaurant chains increasing their profitability.

Atmospheric tasting

Listen to the chefs and you’ll hear conflicting views. When interviewed a couple of years ago, French chef Paul Pairet was quoted as saying that he didn’t believe that all the multisensory atmospherics in his restaurant Ultraviolet in Shanghai made any of his dishes taste better. Rather, he thought simply that “the memory of the dish is stronger.” A worthy enough aim, but is that all there is to it? Ironically, the press report in which Pairet is quoted itself seems to come to a different conclusion. For according to the journalist: “each dish is accompanied by a carefully choreographed set of sounds, visuals and even scents, all intended to create a specific ambience to enhance the flavors of the meal.” Pairet is not alone in his views, though. Others include French chef Alain Senderens, who once complained about the Michelin man’s penchant for fancy fittings. “I was spending hundreds of thousands of euros a year on the dining room—on flowers, on glasses,” he said, “but it didn’t make the food taste any better.”

In the other camp there are those, like Heston Blumenthal, who have latched on to the fact that the atmospherics really can modify the tasting experience. We first demonstrated this with Heston at the “Art and the Senses” conference held in Oxford back in 2007. The lucky participants at this event got to eat oysters while listening to the sounds of the sea and to taste bacon-and-egg ice cream to either the sound of sizzling bacon or the clucking of farmyard chickens. We demonstrated that people rate bacon-and-egg ice cream as tasting significantly eggier when listening to the sound of farmyard chickens clucking in the yard, but when we played the sounds of sizzling bacon instead, suddenly the bacon flavor became rather more intense. Changing the atmospheric sounds altered people’s perception of the test foods. Playing the sounds of the sea also made the oysters more pleasurable (but no saltier).

In the years since, I have been lucky enough to team up with some of the world’s leading drinks brands to conduct various large-scale multisensory tasting events with members of the public. Typically, these events have built on the belief that changing the atmosphere will influence the tasting experience. And rather than manipulating just the sonic environment, we have been working to modify the visual and olfactory aspects of the environment too. Let me share a couple of these experiences with you.

“The Singleton Sensorium”

Typical of this gastrophysics approach was “The Singleton Sensorium,” which took place over three evenings, in the heart of Soho, London, in 2013. My colleagues from Condiment Junkie, a U.K.-based sound agency, decorated three rooms in an old gun-maker’s studio in very different styles. One room aimed to recreate an English summer afternoon, another was designed to prime notions of sweetness, while the third room had a distinctly woody theme. The Condie boys also generated some atmospheric soundscapes to play in the background in each room. Take the sweet room. It was decorated in a pinky-red hue, chosen because that is the color that most people generally associate with sweetness. There was nothing angular in the room; everything was round—the pouf, the table, even the floor plan and the window frames. Why? Well, because our research had shown that people associate rounder shapes with sweetness. There was also the sweet-smelling but non-food-related fragrance and the high-pitched tinkling of what sounded like wind chimes coming from a ceiling-mounted loudspeaker. The latter choice was again based on our laboratory research showing that people associate such sounds with sweetness. So every sensory cue had been chosen on the basis of the latest gastrophysics research to help prime, consciously or otherwise, notions of sweetness on the palate. The first room, by contrast, had been designed to prime grassiness on the nose. The final “woody” room was meant to prime a textured finish, or aftertaste, in the mouth.

Over three evenings, nearly 500 people were escorted in groups of 10 to 15 through an experience lasting no more than 15 minutes. At the outset, everyone was given a glass of whisky, a scorecard and a pencil. They filled in one section of the scorecard while standing in each room. The punters were asked about the grassiness of the whisky on the nose, the sweetness of its taste, and the woody aftertaste. They indicated how much they liked the whisky, and what they thought of the decoration in the room that they were standing in. I was one of the tour guides, and let me tell you, it was an exhausting experience. It was the first time that anything like this had been tried on this scale. Would the experiment work as planned, or would people simply walk away saying that the whisky obviously tasted the same in all three rooms because it was, after all, the same whisky?

It was a huge relief to find, once the results were analyzed, that, as a group, people rated the grassiness of the nose of the whisky as significantly more intense in the grassy room. Meanwhile, the second room brought out the sweetness on the palate (as expected), and the final (woody) room really did accentuate the textured finish of the whisky. As a psychologist, one always worries about so-called “experimenter expectancy effects,” i.e., that your subjects may say what they think you want to hear, rather than tell you what they actually experienced or thought. In fact, at the end of the “Sensorium,” one or two people did approach me and say something of this sort: “We knew what you were up to. You wanted us to say the whisky tasted grassier in the green room, right? So we did the opposite!”

Note, though, that even these truculent individuals were not unaffected by the multisensory environment (at least in a manner of speaking). And crucially, the group analysis revealed that such individuals were clearly in the minority. What is more, people enjoyed the whisky most in the woody environment. So, manipulating the multisensory atmosphere in this scientifically inspired manner really did affect what people had to say about the drink in their hand. Depending on the room, the change in people’s ratings of the nose, taste and finish of the whisky were in the order of 10 to 20%.

Would whisky experts have been equally affected by “The Singleton Sensorium”? It is difficult to say for sure. However, it is worth noting that neither the whisky expert nor, for that matter, the wine aficionado can necessarily do all of the things that they think (or say) that they can when it comes to blind-tasting. What is perhaps more relevant is that the experience was powerful enough for a number of chefs, restaurateurs and designers to go away and change the way in which they delivered some of their food and beverage offerings. For example, staff at one famous restaurant in the Lake District, in northwest England, started serving guests whisky from a wooden tray, matching the environment in which they themselves had most enjoyed the drink while taking part in the event.

“The Colour Lab”

What do you think would be the best colors to bring out the fruitiness and freshness of a wine? And could you achieve the same effect by playing sweet or sour music (sour music tends to be dissonant, high-pitched, rough, sharp and staccato)? We set out to answer these questions in what may well have been the biggest ever tasting event of its kind, known as “The Colour Lab.” More than 3,000 people were tested over an unseasonally warm May Bank Holiday weekend on the banks of the River Thames in London, as part of “The Streets of Spain” festival. Each person was given a glass of Spanish Rioja in a black glass. They had to rate the wine first under regular white lighting (to get a baseline measure), then under red illumination, then again in a green environment with “sour” music. Finally, they tasted the wine under red lighting again, but this time accompanied by “sweet” music. Once again, a 15 to 20% change in people’s ratings was observed on switching from one audiovisual atmospheric combination to another. The red lights and sweeter music (consonant, high-pitched, neither rough nor sharp but smooth and flowing) were found to accentuate the fruitiness in the wine, while the green color and sourer music brought out its fresher notes instead.

While previous gastrophysics research had already demonstrated (albeit on a much smaller scale) that changing the color of the lightbulbs or the music playing in the background can change what people say about the wine they are tasting, we were the first to combine the senses in a multisensorially congruent manner. We were looking for what some have termed a “superadditive” effect. Put simply, this is the idea that the various atmospheric cues might combine to deliver a multisensory effect that was bigger than the sum of its parts (i.e., greater than what you might expect merely from adding the effect of light and sound when presented individually). And as we had hoped, the sonic seasoning—sweet music with red lighting and sour music with the green lighting—did indeed enhance the effect of the lighting on the taste of the wine.

One of the results (or deliverables) of such multisensory events is the statistical evidence that the environment influences people’s perception. On occasion, the results may also reveal the relative importance of the senses to that experience. Often, though, what is much more powerful, at least in terms of convincing people, is the change in what they themselves felt. In fact, when we trialed “The Colour Lab” on the wine makers from Campo Viejo, they were so impressed that they left saying that they would be redesigning their own cellar-door experience as soon as they got back to Spain. Furthermore, one of the wine writers with whom I work, who was, by his own admission, initially skeptical, now uses changes in the ambient lighting as a party trick when leading informal wine tastings. So next time you open a bottle of wine at home and find that it is not quite to your taste, why not just try changing the music and/or the lighting first before you reach for a different bottle? Sometimes, it really is that simple (assuming that the wine doesn’t have any obvious flaws). Nowadays you can buy remote-control color-changing lightbulbs for virtually nothing online. So there really is no excuse, is there?

If you are wondering what counts as sour music, you could try Nils Økland’s “Horisont.” For something sweet, look for tracks with lots of tinkling, high-pitched piano notes. I often use something like “Poules et Coqs” from Camille Saint-Saëns’s Carnival of the Animals or tracks 6 and 7 from Mike Oldfield’s Tubular Bells (1973). Choose something like Carmina Burana by Carl Orff or “Nessun Dorma” from the third act of Puccini’s Turandot if you want to bring out the depth in a red wine, say a Malbec.

These lighting manipulations work well enough when the wine is served in a black tasting glass (as in “The Colour Lab”). I could well imagine that the effects would be even more pronounced if the wine were to be served in a clear glass, where the color of the wine itself may also change as a function of the ambient lighting. You do need to be a little careful here, though, because if too dramatic a change in the lighting is introduced at mealtimes, it may actually change the visual appearance of the food itself. As one commentator put it: “A red light makes everything look red; a green light makes meat look gray and spoiled.”

Of course, different people have different objectives as far as the use of ambient lighting is concerned. While some may wish to bring out the freshness in their wine, others may be wondering whether there are certain colors or, for that matter, types of music that may help to promote healthy eating, for instance, use of red lighting to bring out sweetness (without the calories). Research shows that the color of the ambient lighting can influence a diner’s appetite. For example, yellow lighting was found to increase people’s appetite, whereas red and blue lighting decreased people’s motivation to eat. When the color of the food and of the ambient lighting match, it seems to stimulate appetite, whereas complementary colors suppress it. Also relevant here are the results of a recent study conducted in Sweden, in which it was found that dieting Swedish males eating their breakfasts under blue lighting felt fuller with less food.

Controlling the restaurant environment

So we know what happens in experiential events. But do you think that you would eat less if the lighting and music in a restaurant were softened to create a more relaxed atmosphere? Well, researchers tested the combined impact of changing the lighting and music on the behavior of diners in Hardee’s, a fast food restaurant in Champaign, Illinois. The restaurant in question had two dining areas (ideal for gastrophysics research). In one, the lighting was set at its normal bright level, the color scheme was also bright and the music playing in the background was loud. The other “fine dining” environment had a much more relaxed atmosphere: there were pot plants and paintings, window blinds and indirect lighting. Oh, and did I mention the white-tablecloth-covered tables with candles on top, and soft jazz instrumental ballads in the background? Those who ate in the more relaxed side of the restaurant rated their meal as significantly more enjoyable, while at the same time consuming less (their calorie intake was reduced by an average of more than 150 calories, or 18%).

The fact that the environment has such an effect on us could obviously have implications for the restaurateur. In fact, it has been suggested that this is precisely why the Hard Rock Café and Planet Hollywood chains have no windows, which gives them (just like the casinos) greater control over the environmental stimulation their customers are exposed to.

The future of atmospherics

So, how might the atmospheric aspects of dining change, moving forward? As one designer put it recently: “In the short time I have been in the business of designing restaurants, design has definitely become a major element of the dining experience. The environment and its uniqueness are becoming as important as the food, and designers and owners are becoming more sophisticated in how they use light, color and materials.” And if you want to see what the future may hold in terms of restaurant design, why not take a look at the Goji Kitchen & Bar at the Marriott Bund hotel in Shanghai. The decor in this futuristic dining space actually changes to give the restaurant one of two different feels, depending on the time of day. This is undoubtedly an expensive solution, but it is also an acknowledgment that decor and atmosphere really do matter. It stands as testament to the importance of the atmospheric component of “the everything else” to mealtimes. And while it is always difficult to figure out how much to spend on the decor, as soon as you are aware of just how much it influences the dining experience, then there really is no looking back. However, while getting the atmosphere “right” is undoubtedly a challenge, it is also important to remember that there is no way to avoid its influence, much though one may wish to.

There is an interesting challenge here in terms of how to customize the atmospherics to individual diners, or tables. Currently, most high-end multisensory dining experiences involve either a single-sitting restaurant (think Ultraviolet in Shanghai or Sublimotion in Ibiza) or headphones being brought to the table to accompany a particular dish (the “Sound of the Sea” at The Fat Duck, for instance). However, I know of restaurateurs out there who are already thinking about whether they can use hyper-directional loudspeakers positioned over the tables in order to deliver a soundscape personalized to whatever the diners happen to be eating and drinking. Crucially, none of the diners would be able to hear what was going on at any of the other tables. This kind of solution is currently prohibitively expensive for all but the most affluent of restaurateurs. Nevertheless, looking ahead, I can well imagine that it will become more common, given the growing emphasis on personalization and customization, together with the falling cost of technology.

In this light (if you’ll excuse the pun), there are now multi-colored LEDs installed over each of the tables at The Fat Duck restaurant, following its recent refurbishment. These bulbs subtly change color as the diners at a given table progress on a journey from night to day and on to the next evening during the course of their meal. The lighting changes take place at different times on each table. Is this really the future of personalized atmospherics? I suspect that it might be a start.