9. The Meal Remembered

Humor me for a moment—what would you say was your perfect meal? What exactly can you remember of the experience? What you ate? Who you were with? Perhaps even more interesting: what do you know that you have forgotten? If that is all a bit too much, why not take a more recent dinner instead, the last time you went out to a restaurant, say, and answer the same questions. My guess is that, while you can probably remember where you were and who you were with, the details of the meal itself, the specific flavors and foods you ate, will be much hazier.* Unless, that is, you always order exactly the same dishes in your favourite restaurants, as I do.

No matter how good or bad a meal, it will never last more than a few hours. The mediocre ones we forget, the marvelous occasions hopefully stay burnished into our memories, bringing pleasure whenever we think about them. The really bad ones—well, all too often they stay etched in our minds as well, much though we might wish to forget them! For my brother, the sous vide licorice salmon that he really didn’t like is the dish that he wants to forget but has been unable to, even though he was served it more than a decade ago.

Our memory of a meal, at least of an enjoyable one, is where so much of the pleasure of the experience resides. It can last for days, weeks or even years. From the perspective of anyone trying to sell us a restaurant meal, this is important because it is a major factor in our decision whether or not to return to a particular venue or chain. Our flavor memories also play a crucial role in our decision to stick with one brand or switch to another while browsing the supermarket aisle; once again, such a decision is often based on our recollection of the taste of the product, or what we thought about the experience the last time we encountered it.

What is a food memory?

The simplistic view here would be that our recollection of a meal is merely a weaker version of what happened at the time—“devoid of the pungency and tang,” as William James, one of the godfathers of experimental psychology (and brother of novelist Henry), once so evocatively put it. However, the gastrophysicist knows only too well that our minds play tricks on us. Not only do we forget altogether certain of the things that we experienced so vividly even just a short time ago but we also misremember and confabulate others. More often than you might imagine, we recollect things that probably didn’t occur at all, or at least not in the way we remember them. Our recollections of meals, both good and bad, are no different in this regard.

Storing every detail of an experience (be it a meal or anything else for that matter) in memory would simply be too effortful. So our brains use a number of cognitive shortcuts to help. For instance, we tend to keep track of the high and low points (the peaks and troughs), and how meals start and end (termed “primacy and recency effects”). As a result of another shortcut, we also tend to neglect the duration of events that don’t change much over time. The latter (known, unsurprisingly, as “duration neglect”) has been demonstrated to apply to meals. Such mental heuristics are efficient in that they help us to recall the gist without necessarily having to remember every detail of our lives. However, which elements of a meal will stick (i.e., the end, the peak, etc.) appears to depend on the specifics of the situation.

I would argue that knowing about such “tricks of the mind” is absolutely crucial for anyone wanting to deliver more memorable food and beverage encounters. So, bearing these factors in mind, it’s time to call in the “experience engineers,” the researchers who have made it their life’s work to study what exactly sticks in our memory, and why. The main aim here, in the gastrophysics context, is to get those you serve, whoever they might be, to remember more of the good stuff about your interaction with them. Do you, for instance, still remember the lime gelée incident from the start of the book? One chef in Washington, D.C., Byron Brown, even created a theatrical dining experience in 2011* with the specific intention of enhancing his diners’ memory of the event.

Common sense suggests that the best food and beverage designers—and here I am thinking of the world’s top chefs, molecular mixologists and culinary artists—should be trying to create the ultimate tasting experiences for their customers. However, what those at the top of their game really ought to be focusing on is the creation of the most robust memories possible. Until you get that distinction clear, that our perceptions of food and drink while eating and drinking and our recollections of those consumption episodes differ, both quantitatively and qualitatively, you really can’t hope to deliver the best long-term memories. The meal itself and our recollection of it are linked, obviously, but they diverge from one another in systematic ways that the gastrophysicists and experience engineers know just how to capitalize on.

One of the chefs with whom I work closely, and who has obviously been hanging around me too much, has been running his own experiment (just like a proper psychologist). What he wanted to know was just what his diners remembered of the fabulous meals he served. The chef e-mailed a questionnaire out to his guests a couple of weeks after they had visited his restaurant. He was in for quite a shock! For while those who chose to respond could certainly recall that they had very much enjoyed the experience, what they turned out to be very bad at was remembering precisely what it was that they had eaten. Funnily enough, the kind of thing that made the biggest impression in his diners’ minds was, say, that time when the waitress sprayed some aroma or other over their dish while they were seated at the table. In other words, it was the more theatrical, surprising and/or unusual aspects of service that stuck in people’s minds, far more than the taste of the food itself. This failure to remember the food wasn’t any comment on the quality of the chef’s cuisine. The dishes themselves were delightful. Most were, one would have said at the time, quite memorable. However, it turned out that they weren’t actually remembered that well after all, or at least not the specific ingredients and flavor combinations.

As I am sure you can imagine, this chef really had the wind knocked out of his sails when the results came in. Why, he kept muttering darkly, did he bother putting so much effort into the creation of his dishes if his diners simply couldn’t recall what they had eaten, nor the unusual flavor combinations that he had created? I told the chef not to be too hard on himself, that there was a psychological explanation for all of this and that it wasn’t any reflection on his culinary skills. That the main thing to concentrate on was that people remembered their hedonic response, that they had really liked “the experience.” And, if they also happened to engineer a memory of some confabulated meal, a construction of their overactive imaginations, well, so be it. It was especially surprising to hear from those diners who were convinced that their memories were so vivid they could almost taste the dish again. They were, as likely as not, imagining the flavor of something that they hadn’t tasted, at least not at this chef’s table! (All of this ought to make one wonder about the value of those online reviews.)

Using my most consoling tone, I told the chef that it was no use to try to fight the foibles of recollection. What he needed to do instead was to better understand the many ways in which memories fade and our minds deceive us. We mostly do not pay attention to what we taste. Rather, our brains just do a quality check first, to ensure that there is nothing wrong with the food or drink and that it tastes pretty much as we expected (or predicted) that it should. After that, once we know that we are safe, we devote our cognitive resources (what the psychologists call “attention”) to other, more interesting matters, like our dining companions, or what’s on the TV or who has just sent us a text. That is, we no longer feel any need to concentrate on what we are consuming. And, as psychologists know only too well, unless you pay attention (e.g., to what you eat), you have little chance of remembering, even a few moments later, never mind after a few weeks or months. Emotion may also play a role here.

In fact, if you change the flavor of a food while eating (and yes, the experiment has been done), people often don’t notice. It is as if we are all in a constant state of “olfactory change blindness.” Intriguingly, this is something that the food companies have been trying to exploit to their, and hopefully our, advantage for a few years now. The basic idea is that you load all the tasty but unhealthy ingredients into the first and possibly last bite of a food, and reduce their concentration in the middle of the product, when the consumers are not paying so much attention to the tasting experience. Just think about a loaf of bread with the salt asymmetrically distributed toward the crust. The consumer will have a great-tasting first bite, and then their brain will “fill in” the rest by assuming that it tastes exactly like the first mouthful did. This strategy will probably work just as long as the meal isn’t high tea and the taster eating cucumber sandwiches with the crusts cut off! Or imagine something like a bar of chocolate, which most people will presumably start and finish at the ends, not in the middle. In fact, Unilever has a number of patents in just this space.

This innovative product development strategy is based, on the one hand, on the phenomenon of “change blindness” and, on the other, on the assumption our brains make that things that appear the same probably taste the same too. The promise of the latest gastrophysics research is that by understanding such “tricks of the mind,” food and beverage companies, or at least the more innovative among them, will be able to deliver the same great taste that the consumer has come to expect without as much of those ingredients that we should all be consuming less of, like sugar, salt and fat.

Choice blindness

Do you think that you would notice the difference between two jams with a similar color and texture, or two different flavors of tea? Most people will answer these questions in the affirmative. After all, isn’t the very reason we buy one kind of jam rather than another, or keep multiple types of tea in our homes, precisely because we can differentiate their flavor? And yet gastrophysics research has highlighted some pretty worrying limitations concerning our perceptual abilities. It turns out that we actually have surprisingly little recollection (or awareness) of even that which we tasted only a few moments ago. In one classic demonstration of this phenomenon, known as “choice blindness,” shoppers (nearly 200 of them) in a Swedish supermarket were asked whether they would like to take part in a taste test. Those who agreed were then given two jams to evaluate. They were similar in terms of their color and texture (e.g., blackcurrant versus blueberry). Once the shoppers had picked their favorite, they sampled it once again and said why they had chosen it, and what exactly made it so much nicer than the other jam. The shoppers were more than happy to oblige, regaling the experimenter with tales of how it was their favorite, or that it tasted especially good spread on toast, etc.

What many of the shoppers failed to notice, though, was that the jams had been switched before they tasted their “preferred” spread the second time around. The experimenter was using double-ended jam jars in order to effect this switch unnoticed. In other words, the unsuspecting customers were justifying why they liked the spread that they had just rejected. Exactly the same thing happened in another experiment with fruit teas. Overall, the deception was noted by less than a third of shoppers. Even when the jams tasted very different—think cinnamon-apple and bitter grapefruit jam, or the sweet smell of mango versus the pungent aroma of aniseed-flavored tea—only half of the switches were detected. What these findings imply is that many of the people tested actually did not have a clear memory of the flavor of the food that they had tasted only a moment or two earlier.

Such results, surprising though they undoubtedly are, nevertheless fit well with the research on blind taste tests. Consumers are convinced that they can pick out their preferred brand when given a range of alternatives to taste blind (i.e., without being able to see the labels). Time after time, they select one product and confidently assert that it is most definitely their preferred brand (presumably by comparing the taste to their memory of the taste). Why else, after all, would they be paying more for a branded product than for a cheaper unbranded or home-brand alternative? Only the thing is, in most cases the brand that they so confidently pick out happens to be something other than the brand that they normally choose. It is not that all of the products taste the same; more often than not they don’t. It is just that our flavor memories aren’t quite what we take them to be.

But surely this is not applicable to every product? Some of my colleagues always pipe up at this point that things are very different in the world of wine. They protest that I shouldn’t believe the results of all those blind wine tasting studies in which people perform so badly, even the experts. And, truth be told, there certainly are some remarkable feats of blind wine tasting out there; that I don’t doubt. But it is important here to distinguish between two alternative scenarios. On the one hand, there is the case of the expert who tries a wine blind and suddenly has a flashback to some long-ago vineyard where s/he first tasted it, remembering also who they were with and even what shoes they were wearing. In the alternative scenario, on the other hand, a more measured and rational assessment of a wine’s sensory properties is undertaken by the taster. In the latter case, a careful process of elimination helps the expert to determine what the likely provenance of the wine is. Both can, of course, be most impressive, but only the former can really be said to demonstrate an outstanding feat of sensory flavor memory. It is interesting in this regard to see how guides to blind wine tasting tend to focus on the second approach. I suspect that, more often than not, the amazing feats of blind wine recognition are a matter of inference and cool calculation, rather than taste/flavor memory.

Have you heard of “Sticktion”?

“In the context of experience management, [Sticktion] refers to a limited number of special clues that are sufficiently remarkable to be registered and remembered for some time, without being abrasive. Sticktion stands out in the experience, but does not overpower it; well-designed, it is both memorable and related to the ‘motif’ of the experience.” For all of you out there who are interested in knowing how to manage your customers’ (or, for that matter, your friends’) food and drink experiences, the good news is that there are various strategies that can be used to create “stickier” memories, positive recollections that will hopefully form the basis of a decision to return to a given restaurant (or for those cooking at home, that will have your friends reminiscing about what a great cook you are). One suggestion is to deliver an unexpected gift, such as an amuse bouche, a little taster from the kitchen that the diners (or your guests) hadn’t been anticipating, and certainly hadn’t ordered. This is just the kind of positive surprise that is likely to stick in their memories long after they leave.

Similarly, the rise of the multi-course tasting menu also provides the opportunity to create stickier interactions, with the first taste of each and every dish providing a potential moment of “flavor discovery.” Serving a large plate of the same food is, from the point of view of engineering great food memories, absolute madness. You know that people will remember the first few mouthfuls and that is it. This is the “duration neglect” that we heard about earlier. The rest of the food will be lost to recollection no sooner than the plate has been cleared from the table. A wasted opportunity if ever there was one!

Anyone who is trying to design “great-tasting memories” should probably also be thinking about primacy (and recency) effects here. Let me explain: if I were to give you a list of items to remember, like, say, the names of the dishes on a tasting menu, then you would be more likely to retain the first few courses and the last. The middle items will have to do more to stand out. No wonder, then, that so many chefs seem to really excel in their starters (not to mention their amuse bouche). Perhaps one can think of this as an intuitive example of experience engineering. If you know which dishes are most likely to end up sticking in people’s memory, then working on really perfecting them can be time well spent, in terms of leaving your guests with the best impression (or memory) possible. Looking forward, it ought to be possible to figure out an ideal balance in terms of the number of courses that diners will have a reasonable chance of remembering while at the same time offering the chef enough scope to show what they are made of.

Just take the following as illustrative of the problems associated with trying to create more memorable food experiences. In one study, conducted in a restaurant, one-third of the diners questioned had no recollection whatsoever that they had eaten any bread, even minutes after having done so. This ought to make you think differently about how much effort you should put into that particular aspect of your dining experience. Indeed, it does seem like a growing number of restaurants in cities like New York no longer offer their diners bread. Intriguingly, it would also seem to argue against a primacy effect. But perhaps it is just that people simply don’t think of the bread as a meaningful part of the meal. Perhaps it is treated as background, like the tablecloth, rather than the foreground experience of the dishes themselves.

Those experience engineers who have studied people’s memories of mainstream restaurants find that our recollections rarely revolve around food. Just take the following as a case in point: when more than 120 customers who had eaten at a branch of the U.K. chain Pizza Hut were questioned a week after their visit, it turned out that the enthusiasm of the opening exchange with the restaurant staff—the warmth and energy with which the employees introduced themselves—was the single most salient memory for most of them. What was also important was how long it took to be acknowledged by a member of staff. Ultimately, if you know what your customers are most likely to remember, you are going to be in a better position to modify your food service offering, no matter whether you are a Michelin-starred restaurant or a gastropub. Knowledge really is power!

Do you remember what you ordered?

But, I hear you say, while the specifics of the tastes and flavors of the dishes that we have eaten previously might well fade from memory, don’t we all at least remember our favorite dishes, or perhaps the chef’s signature plate at the local eatery? For me, in my neighborhood Italian, it is always fried whitebait followed by cannelloni con carne. That is something that I never forget.* And whenever I find myself out for an Indian, then it’s chicken jalfrezi, pilau rice and peshwari naan. The regularity with which I order exactly the same dishes is one of the things that convinces my wife that I am on the autistic end of the spectrum! But I would say it’s not so much a question of neophobia (versus neophilia), but rather, if you know what you like, why change?

It is here that restaurants like The House of Wolf in Islington, north London, tend to fall down. Its business model was to offer a dining space for pop-up chefs and culinary artists, each doing a 4–6-week stint. Individually, each of the chefs who came into the kitchens was great. But they were also very different, one from the next. Hence, while you may be able to remember that you liked the chef who was cooking last time, you don’t really have any specific positive memories of the dishes that might encourage your return, i.e., there is nothing concrete to look forward to. The management gurus are absolutely clear on this point: any really successful restaurant needs to have a few staple dishes that they are known for, dishes that customers remember and will come back to experience time and again. And indeed, The House of Wolf, just like many other restaurants with an ever-changing menu, didn’t last long (the leaking roof probably didn’t help much either). A shame, really, as I used to enjoy my role as professor-in-residence there. By contrast, think of those restaurant chains such as L’Entrecôte, where the menu is essentially fixed. That is precisely why the customer looks forward to returning—to eat exactly the same food that they remember so well from every previous visit. There are even those, like my wife’s family, who have been dining at L’Entrecôte for more than four decades now, despite the perennially long queue, as you can’t book a table (see also “The Personalized Meal”). Presumably the queuing is also part of “the experience,” lending what appears to be some scarcity value.

Do you remember what you ate?

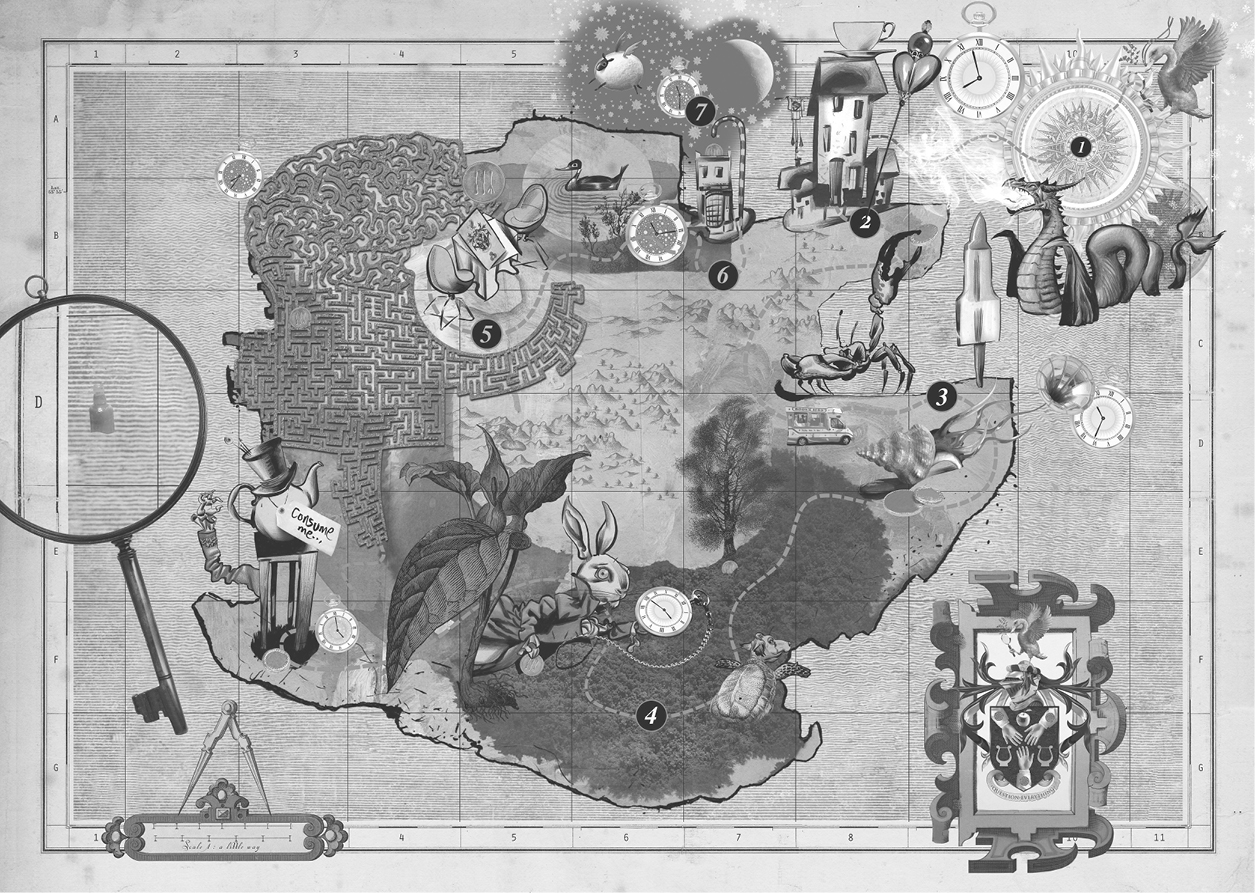

Another technique that can help one’s diners to create memorable dining experiences is to tell stories around the food. Eating at The Fat Duck restaurant is a good example. The experience starts with the diners being presented with a map and magnifying glass complete with duck’s feet (see Figure 9.1). The idea that you are on some kind of journey has been ramped up, even while many of the dishes have stayed pretty much the same. Storytelling can, I think, help the diner to make sense of a multi-course tasting menu—a series of dishes that might otherwise seem like a random sequence from the chef’s own personal hall of fame (a selection that might seem sentimental, even). By providing a storyline, a narrative framework, not only will the diner be better placed to parse or “chunk” (that is, to group together items so that they can be processed or memorized more easily) the whole experience, but once “chunked,” the experience will be easier to remember too. This becomes all the more important once we have lost the more traditional structure of the three- or five-course meal.

Figure 9.1. The map that diners are given to inspect (with the aid of a magnifying glass) on arrival at The Fat Duck.

For special meals, it can also be a good idea to give the diner a copy of the menu to take away with them. The walls of the kitchen at home are adorned with framed examples of fabulous meals, like the menu from my first visit to Heston Blumenthal’s restaurant in Bray. Even though it is now nearly fifteen years later, reading the descriptions of the dishes on the wall is all it takes to trigger so many pleasant memories (not necessarily of flavor, you understand, but rather recollections of the meal itself, and what I imagine the dishes could have tasted like). And, in this case, presumably, the more descriptive the menu, the better.

Even better, at least in terms of creating a lasting (or “sticky”) impression, was what happened when the menu was placed on the table midway through that meal. I still remember, just as vividly as if it was yesterday, picking up what looked like a regular vellum envelope, hoping to remind myself of the dishes that I had already polished off (and which I was already starting to forget—there had, after all, been so many) and to see what was coming next. I was shocked to feel something under my fingertips that had the texture of skin (the envelope had been specially treated). That was not at all what I had been expecting, and that moment of “hidden surprise” has stayed with me ever since. Indeed, as noted earlier, more often than not it is the unusual or surprising experiences, the ones that capture our attention, that really force us to stop whatever else we may be doing (or concentrating on). It is the moments where we have to figure out what it is, exactly, that is going on that are remembered best. It is those events (and dishes) that need to be processed more thoroughly in order to be understood that will really stick in your memory. This is what the psychologists describe as “depth of processing”; the deeper the processing, the better our recollection will be.

A final suggestion here, in terms of creating better food memories, relates to what is known as the “end effect.” Our recollections of experiences tend to be dominated by what happened at the end, and food is no exception. Consequently, ending a meal on a high note can lead to greater remembered enjoyment. In one simple demonstration of this effect, researchers gave eighty people an oat cookie followed by a chocolate cookie. Another eighty people ate the cookies in the reverse order. Those who finished their snack with the more enjoyable chocolate cookie remembered the food as having tasted better when quizzed thirty minutes later. The end effect is presumably also what explains why “all you can eat” meals are unlikely to be remembered too fondly. The end in such cases, at least in my personal experience (as a student, I hasten to add), is that feeling of being unpleasantly stuffed and knowing that you have eaten more than you should have. By contrast, those Italian restaurants where the meal ends with a surprise shot of limoncello might well be engineering a more positive memory, by ending the encounter with a mood-inducing unexpected gift. So, why not think about what you can do to surprise your dinner guests before they leave the table?

What is so special about mindful dining?

The next time you find yourself eating in front of the TV or computer, think carefully about what you are doing. As we have seen already, mindful (or attentive) eating and drinking is important, and anything that we can do to make ourselves more aware of what we are consuming is going to help in terms of increased enjoyment, enhanced delivery of multisensory stimulation, and quite possibly increased satiety too. But does mindful dining and drinking also lead to better memories of food and beverage experiences? It certainly feels like this ought to be the case, and that eating mindfully would also lead to reduced consumption subsequently (be it later in the meal or in subsequent meals). However, I think that we need to await further gastrophysics research in order to know for sure. That said, there is, I suppose, a sense in which the many diners taking all those pictures of their food and posting them on social media are creating an external memory of the event, and of the dishes themselves. They are an aide-memoire, if you will. It is those images, more than anything else, that will help people to remember what they probably know they will otherwise forget.

Away from the restaurant, though, one might ask what exactly we remember of our favourite foods? Consumers often complain whenever too drastic a change is introduced into the formulation of their favorite brands—the consumer backlash that was triggered by the introduction of New Coke or by the change in the shape of the Cadbury Dairy Milk bar, for example. Such behavior could certainly be taken to imply that we must retain the taste of our favorite foods in memory. However, it turns out that our recollection of branded foods and beverages may only be as good as the last consumption episodes. This, after all, is what enables the food and beverage manufacturers to engage in their health-by-stealth strategies, gradually cutting the amounts of unhealthy ingredients, like sugar or salt, in their products without consumers ever realizing that anything has changed. Do it too fast and you’ll have the consumer writing, calling and e-mailing in to complain that their favorite brands no longer taste the way they did! The challenge for the food companies is made all the more difficult, though, by the fact that even extrinsic product changes, such as to the color of the can or the shape of the chocolate, can affect the perceived taste of the product (and give rise to an increase in consumer complaints), even if the formulation itself hasn’t changed (see the “Sight” chapter).

The gastrophysicist will tell you that as soon as we are alerted to a change or a potential modification (e.g., when we read “low fat” or “reduced salt” on the label) we start to pay more attention to what we are tasting. Thus it is normally a bad idea for a company to market a new reduced-fat, -sugar, or -salt product as such because that is likely to set expectations about the taste in the mind of the consumer (as discussed earlier), who will then pay more attention to the taste, looking for any differences. This is rarely a good thing. For as the Dutch sensory scientist Ep Köster notes, as far as the senses of smell, taste and mouthfeel are concerned, memory seems to be focused on detecting change rather than on identification and precise recognition of the food stimuli that we have encountered previously.

So, how are we to make sense of all this—failure to identify our favorite brands in all those blind taste tests on the one hand, and consumers’ vociferous complaints when they perceive that their favorite brands have changed on the other? It doesn’t seem to quite add up—or does it? Well, maybe we remain essentially blind to taste, i.e., we pay no attention unless our brains happen to detect that something is not quite as we expected it to be. Only then do we really start to concentrate. So if you are trying to nudge your family toward slightly healthier eating behaviors, the implications are clear: introduce changes to your cooking (such as reducing the salt) gradually, and whatever you do, don’t let them know what you are up to.

The meal forgotten

I wouldn’t want you to think that the “meal remembered” is only of interest to those who, like in the movie Total Recall, want to insert particular memories into your mind (be it for financial or commercial gain). There is also an important element to this research, relevant to all of those unfortunate individuals who are losing or have totally lost their ability to recollect recent events, those who can forget, just as soon as the dishes have been cleared away from the table, that they have just polished off a three-course meal. For instance, amnesic patients suffering from Korsakoff’s Syndrome (normally resulting from extreme alcoholism) may retain no memory whatsoever of having just eaten, and will happily start a second and even a third meal, if it is placed before them, providing they are momentarily distracted after the last meal has finished. One solution here is to leave visual cues of a recently finished meal lying around to provide an external reminder of the meal that has just been eaten.

In a related vein, a few years ago, I was a consultant on a project with a London-based scent expert and a design agency to help develop an intervention for early-stage Alzheimer’s/dementia patients who forget to eat. The basic idea was that if these patients could be reminded to eat, they could maintain a semi-independent existence for a little longer than might otherwise be the case. The solution that my colleagues came up with is a plug-in that releases the scent of breakfast in the morning, of lunch at—you guessed it—lunchtime and enticing dinner aromas in the evening. The product has been available commercially for a few years now. In this case, one of the challenges for the gastrophysicist was to figure out which aromas to use, for while the smell of sizzling bacon might work as a breakfast cue for some, it clearly isn’t an option for those who abide by certain religions. Furthermore, the foods we eat also change as the decades go by. So we had to try to find those food aromas that would be meaningful to individuals who were mostly expected to be of retirement age.

The importance of developing such sensory interventions becomes clear once you realize that close to 50 million people worldwide are currently suffering from dementia. In a small test of the designed solution, called “Ode,” fifty people living with dementia (along with their families) used the device for almost three months. The weight of more than half of those who took part either stabilized or increased, leading to an average weight gain of two kilograms. No wonder that it was voted the most innovative British Business Idea of 2013 by Small Business Cup.

Hacking our food memories

There is also a really interesting line of research into the “hacking” of food memories to bias people’s food behaviors. For instance, researchers have shown that people’s attitudes and behaviors around food can be subtly influenced simply by implanting false memories related to prior food-related experiences (e.g., telling someone that they once became ill after eating beetroot). Such misinformation, and the false memories that it can give rise to, can lead to significant behavioral change (e.g., lowered self-reported preference for and decreased consumption of beetroot). While the majority of the research conducted to date has been in the laboratory, there is growing interest in using such techniques to try to nudge people toward adopting healthier food behaviors. Could children, for instance, be encouraged to eat more vegetables by implanting false positive memories around previous pleasurable consumption episodes? And if they could, would it even be ethical to do so?

Remember, remember . . .

Ultimately, all that stays with us, once the meal is over, is our memory of it; we have only our recollections of the great occasions, and of the terrible ones too. The stuff in the middle—well, that is mostly just forgotten. Chefs, at least those with an eye on the future, would like to create food experiences that are more memorable, that have more “Sticktion,” in the words of the experience engineers. Their long-term success, after all, depends upon it.

It is our recollection of the taste and flavor of foods that determines which restaurants we go back to, which food and beverage brands we stay loyal to, and even how much we decide to eat. In fact, simply reminding someone of what they ate earlier in the day (for lunch, say) can be enough to lead to a significant reduction in their subsequent snack consumption, when compared to those who were encouraged to recollect what they ate for lunch the previous day instead. Remembering what you have eaten recently can therefore be more important than you might have thought. Fortunately, the gastrophysics approach is increasingly assisting those who want you to recall more, as well as helping to improve the quality of life for those who can no longer remember.

And, although there isn’t space to cover the topic in any depth here, consider too that the foods we eat can themselves also be used to evoke memories, as captured by the oft-cited case of Proust’s madeleine. And just think of those so-called “memory meals,” like Thanksgiving in the U.S.

Let me end, though, with Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin’s quote on taste and flavor in aging, from his classic book The Physiology of Taste, published in 1825. The famous French gastronome writes: “The pleasures of the table, belong to all times and all ages, to every country and to every day; they go hand in hand with all our other pleasures, outlast them, and remain to console us for their loss.” As the old polymath knew only too well, eating and drinking constitute some of life’s most enjoyable experiences. When our memory of those pleasures go, one might ask: what else is left?