12. Digital Dining

Would your cocktail taste as nice or your dinner as delicious if you found out that it had been prepared by a robot? Would you trust a robot chef to season your food for you? Really? And how would you feel about being served by a robot waiter? Sounds like science fiction, right? Well, these things are already becoming reality, albeit in only a small number of venues so far. Like it or not, a whole host of digital technologies have become ever more closely intertwined with our everyday experience of food and drink. There are already digital menus out there that will send your order straight to the bar or kitchen. Pizza Hut even trialed a “subconscious” menu that could, or so it was claimed, magically read your mind and tell you the three toppings that you wanted on your pizza, without you having to say a word. The menu tracked the customers’ eye movements while they viewed the digitally displayed options. No worries, though, if you happen not to like what your subconscious chose, as you could always stare at the restart button and begin the process all over again! I have to say, though, that this example smacks of marketing gimmickry rather than a serious attempt to envision the restaurant of the future. Elsewhere, though, one comes across headlines talking of a “Star Trek ‘replicator’ that can recreate ANY meal in 30 seconds.”

Soon there may no longer be any need to reach for the sugar. At least, not if you know about the latest findings from the field of sonic seasoning, which can be dispensed by the mobile devices that so many of us now carry around with us. In fact, digital artifacts will probably become a ubiquitous part of our multisensory food and drink experiences in the near future. It is more than likely that we will first come across these new technologies at the tables of some of the world’s top modernist restaurants or cocktail bars. But from there, it is only a few short steps to their introduction in chain restaurants and the home environment.* Furthermore, many global food and beverage brands are eager to get a slice of the action here too. So let’s jump straight in and see what tomorrow’s digital dinners might look like, and who—or should that be what?—exactly might be making them.

Would you like a 3D food printer?

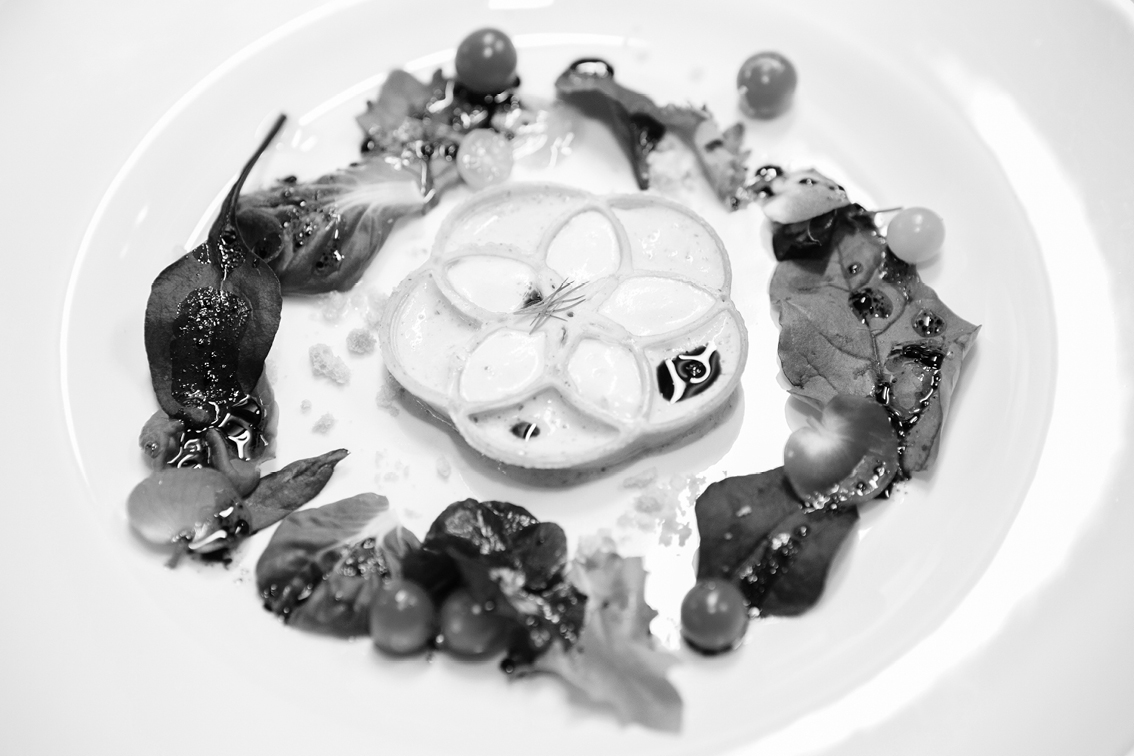

Read the newspapers and you’d be hard pressed not to come away with the belief that the 3D food printer is going to be the all-new must-have gadget in the home kitchen. If you haven’t heard about the Foodini, the Bocusini or the (rather more mundanely titled) 3D Systems ChefJet Pro 3D, then you are probably not an “it” cook. Chefs are now using 3D printers to impress diners by creating foods the likes of which they have never seen before (see Figure 12.1 for one beautiful example of 3D food printing). So will the 3D food printer really become the microwave of the future? It is obviously in the best interests of the manufacturers to try and convince you that it is, but I beg to differ. Don’t get me wrong, it’s not that I see no use for them, it’s just that my best guess is that they will end up in the kitchens of a few fancy modernist restaurants and in food innovation centers, not in the home kitchen (one of the few exceptions to my earlier predictions that what starts in the modernist kitchen and restaurant will trickle down and eventually find itself in the local restaurant or even the home).

One chef who has apparently become enamored with the possibilities offered by 3D food printing is Paco Perez. He uses one at his restaurant La Enoteca, at the Hotel Arts in Barcelona, to create food forms that could not otherwise be made (intricate architectural renditions of famous buildings, for instance). I was also intrigued by the recent release of an inkjet printer that allows the barista to create amazing latte art (e.g., showing realistic portraits of famous people). And until his untimely death a few years ago, Homaru Cantu was famous for printing edible menus for his restaurant Moto, in Chicago. The inventive chef managed this trick by hacking a regular printer. In May 2013, NASA offered him a six-month Phase 1 study contract to develop printing technologies capable of combining shelf-stable macronutrients, micronutrients and flavors to produce personalized food products for long-duration space missions. Cantu generated lots of excitement when he started talking to the press, especially when he mentioned the future of printing 3D pizzas in space. When the story broke, though, NASA was outraged. A number of those working in the area felt that all the press coverage largely demeaned (and distracted from) the serious science underpinning the development of adequate food supplies for long-distance space flight. No wonder, then, that funding for Cantu’s project was not extended to the next stage.

Figure 12.1. “Caesar’s Flower of Life”: seasoned bread in 3D-printed sacred-geometric “Flower of Life” design, with assorted flowers and vegetables. An eclectic eight-course dinner was 3D-printed and served using byFlow Focus 3D-Printers, prepared with fresh natural ingredients and borrowing innovative multisensory techniques from the world of molecular gastronomy.

Currently, commercial food printers are still a little too expensive for widespread home uptake, coming in at somewhere around $1,000 apiece. In time, that figure will probably come down, as it always does with technology. But even if they were giving them away, I still wonder who would be daft enough to get one for their home kitchen. Should you be wondering why I have become so curmudgeonly all of a sudden, well, you need to ask yourself how long it actually takes to print each perfectly formed morsel of food. My guess is that you would probably have to start preparing your very own unique pasta shapes a good few days in advance if you were thinking of inviting all your friends over for dinner. So while you could make it yourself with your new kitchen toy, don’t forget we still have those quaint things called shops. And if you do find yourself craving a printer, just ask yourself who, exactly, is going to clean the tubes out each time after you have used your glistening new kitchen appliance. You might also wonder how much your electricity bill would go up. So, I ask you once again, is it really worth it?

3D-printed foods have novelty value, yes. But, beyond that, what new food experiences could they possibly give you? Is there a unique selling point here? What is it, exactly, that this machine allows you to do that you couldn’t do otherwise? And even if—for some unknown reason—sales of 3D food printers do eventually pick up, my guess is that you will find all these sorry devices stored away lonely and unloved, collecting dust at the back of the cupboard, within a couple of years of the hype reaching its apex. That is to say, they will end up in exactly the same position as so many of those home breadmakers and food processors—the must-have kitchen appliances of recent decades.*

However, I could imagine creating the perfectly shaped chocolate, one that snugly fit the contours of the average human tongue and could therefore deliver a more intense flavor hit than any one of those seemingly accidentally shaped confections currently out there in the marketplace. Just imagine a chocolate that stimulated all of your taste buds simultaneously. But as soon as the perfect shape had been identified (assuming, of course, that there is one), then the industrial production lines could be reconfigured to create it on a massive scale.

So, if you believe me when I say that we are not going to be eating 3D-printed dinners at home any time soon, then where else might we first experience the intrusion of digital technology into our food and beverage experiences? Well, many of you will have come across the next one already, namely the digital menu.

Do you like ordering from a digital menu?

No, me neither, though one does increasingly find digital menus in trendy high-end bars and restaurants. Now, this ought to make sense, right, at least on paper? No more worries that your waiter will forget something when they stubbornly refuse to write anything down when taking the orders. Digital menus should also allow for any changes to the vintages of the wines to be updated on the list in pretty much real time. This would at least deal with one of my pet peeves—when restaurants have one vintage on the wine list and then bring out a (generally inferior) younger bottle because they have run out of the good one, often without telling you (and expecting you to be happy to pay the same price for it). And, in theory, the digital menu should enable the restaurateur or bar owner to incorporate any seasonal dishes or drinks on to their menu, thus allowing them to bin the blackboard—you know, the one with the daily specials chalked all over it.

And yet, if you are anything like me, you will have realized that it just doesn’t feel right. Maybe it is because I am not a millennial, but I have to say that when someone insists that I order from a digital menu, the dining/drinking experience is somehow diminished. Why so? Well, there are a couple of reasons: on the one hand, it is important, I think, to remember that dining is a fundamentally social activity (see “Social Dining”). Part of the reason that we go to a restaurant or bar in the first place is for the interaction with the staff. Danny Meyer, one of the most successful restaurateurs of our time, nailed it, I think, when he said: “Despite high-tech enhancements, restaurants will always remain a hands-on, high-touch, people-oriented business. Nothing will ever replace shaking people’s hands, smiling, and looking them in the eye as a genuine means of welcoming them. And that is why hospitality—unlike widgets—is not something you can stamp out on an assembly line.”

There are no two ways about this: digital menus take away from that social exchange and make for a much more transactional kind of experience. Some would say that placing an order from a digital menu is just cold. I, for one, am glad to see that restaurateurs and bar owners are slowly coming to their senses and getting rid of their digital menus. And not before time either, if you ask me. The only place where they make sense, I think, is in those venues where all that anyone wants is a rapid and efficient transaction, say, when grabbing a quick bite to eat at an airport.*

The other problem is that most digital menus look pretty much identical to the printed version. Why? Surely, going digital should be an opportunity to do something radically different. If a modernist chef were to present you with one, someone like Grant Achatz in Chicago, or Juan Maria Arzak in Spain, you know that it wouldn’t simply be a digital replica of a paper menu. One of the few interesting examples is the digital menu that one sees on the table at Inamo, an Asian fusion restaurant in London. Not only can you order simply by touching the relevant item projected on to the table’s surface but you can also see what the various dishes look like before ordering them.* The digital nature of the interaction also means that presenting pictures of the dishes doesn’t seem anything like as tacky as it would if exactly the same images were to be displayed on a regular printed menu. There is, then, a tangible benefit here for the diner from “going digital.” You can even order a taxi home directly from the table-top! Of course, given the growing interest in where the food we eat comes from, one could also imagine being shown information about the history of the ingredients, which farm they came from, etc.

Digital menus also offer the possibility of delivering a more curated meal. Take Mother in Stockholm, where the menus are also projected directly on to the table-top, and the diners are quizzed about which foods they prefer. Then, a number of recommendations are made for dishes that the diner might like. (The only missed opportunity here is the fact that the system does not keep your details from previous visits—a trick of personalization that, as we have seen, is likely to make a meal both more enjoyable and more memorable.)

One other interesting use of digital interactive menus comes from The Weeny Weaning restaurant opened by Ella’s Kitchen in 2014. This, the world’s first sensory restaurant for babies, has been designed to encourage healthy eating from an early age, or so the blurb goes. According to one report: “Little ones will be seated in highchairs at interactive tables, from which they will be able to choose from their very own digital menu, allowing them to order their own mains and desserts [. . .] Depending on the number of times they tap a particular food icon over a 30-second period, the digital menu responds accordingly and the waiters bring the children their selected choice of food.” The next generation are likely to be much more open to this kind of digital interface with food, no matter whether or not they were exposed to it as a baby.

Tasting the tablet

Why would you use a real plate when you can use a tablet instead? (Or should I have said that the other way around?) This is, though, one of the ways in which technology has already started to change our visual experience in the modernist restaurant; there are chefs who serve some of their food from tablet computers rather than plates. (Who knows, perhaps this is the perfect way to make use of all those surplus tablets sitting around in all the restaurants and bars where they have figured out that digital menus are a waste of time!) Chef Andreas Caminada recently served one of the courses at his Swiss restaurant on top of a tablet displaying the image of a round white plate: an ironic take on digital plating.

A few years ago, we were playing around with the idea of serving seafood from a tablet (see Figure 12.2). The diner would catch a glimpse of the sun glinting off the waves and the sand on the seashore, so realistic that they could almost touch it. That was the hope anyway! Combine the sight of the seashore with the sounds of the sea (about which more below), and the seafood may well taste better. At the very least, plating from a tablet should offer the creative chef increased freedom as far as the storytelling around a dish is concerned. While so far this is happening only in a few cutting-edge restaurants, one could imagine, in the future, all of us repurposing our own tablet computers at mealtimes.

Some of you out there will be appalled: why on earth would I spend good money on a tablet computer only to eat off the damn thing? you may be muttering darkly to yourself. What, exactly, is so wrong with the good old-fashioned round white plate? Has the professor actually lost his marbles? Don’t get me wrong, I am certainly not saying that the tablet is going to be the ideal option for every kind of food. Even I can’t imagine that it would be much fun trying to eat a big juicy steak, say, from a tablet. Probably best to keep serving this one on a wooden board. Canapés and other finger foods might be more the thing, at least till you get the hang of this all-new digitally enhanced plateware.

Figure 12.2. How long before high-end restaurants start serving food from a tablet rather than a round white plate? Top Spanish chef Elena Arzak says: “At Arzak in San Sebastián, certain dishes are served over a digital tablet: grilled lemons with shrimp and patchouli sit atop a fired-up grill with the noise of crackling flames [. . .] We experimented with serving the dish on and off the tablet and diners always said that having the image and the sound intensified the flavors of the dish and made it even more enjoyable. We’re keen to use new technology to further augment the meal.”

In my defense, though, let me at least point out that some tablets are waterproof so you could, I presume, put them in the dishwasher straight after use, should the need arise. (Perhaps the professor has lost his marbles after all!) I can easily foresee how serving food off a tablet could also provide the ideal means of ensuring the perfect color contrast between your food and the plateware (or, in this case, the tablet screen) against which it is viewed (see the “Sight” chapter). Ultimately, though, I think that eating from a tablet will go mainstream only if the diner’s experience of the dishes served in the modernist restaurant is radically altered, i.e., enhanced, by whatever is shown on the screen. And for those of you who might be thinking that the price would be too high, just remember that at some of the world’s top restaurants individual plates designed for just one dish have been known to come in at more than £1,000 a pop. Plating off a tablet might seem cheap by comparison.

Would you like to eat cheesecake on Mars?

This is what the creators of Project Nourished are offering with their recent attempt to combine virtual reality with food. Developed by Kokiri Labs, in LA, Project Nourished is described as a “‘gastronomical virtual reality experience.’ This mashup of molecular gastronomy and virtual reality allows users to ‘experience fine dining without concern for caloric intake and other health-related issues.’” Their strapline is “Wouldn’t you like to eat cheesecake on Mars?” Said almost rhetorically—for how could you resist? You must, at the very least, be a little curious. And, given what we have seen in previous chapters—how much impact context, atmosphere and environment have on dining and drinking—you can be sure that your cheesecake probably would taste a little different if you were wearing one of these headsets, assuming, that is, that the experience is suitably immersive, and all that virtual space dust doesn’t blow into your eyes! Looking a little further into the future, it is interesting to consider how the various new augmented and virtual reality (AR and VR respectively) technologies are going to enable the diner of tomorrow to eat one food while simultaneously viewing another.

So what exactly do we all have to look forward to, in this mash-up of food and virtual reality? Well, here’s a hint of what may be to come, at least if the techno-geeks have their way: “As for Project Nourished, here’s the deal: You put on your VR headset, [. . .] you lift your ‘food detection sensor,” which, at this stage of development, looks like nothing more than a wooden fork with two prongs wrapped in tinfoil; you eat a hydrocolloid—a flexible substance that is “viscous, emulsifiable, and low caloric”—that has been shaped in a 3-D printed mold to “add physical characteristics to the ‘faux’ food.” Then, with the help of a motion sensor, an aromatic diffuser, and a bone conduction transducer [. . .] you experience a gourmet meal with no downside in the way of calories, carbs, or allergy-inducing ingredients.” Don’t tell me you are still not convinced!

The more fundamental worry, though, is simply that the idea of eating cheesecake on Mars doesn’t seem like an especially congruent combination, at least not to me. Perhaps we’d be better off matching the food to the environment that we are immersed in via the headset, maybe a strawberry-flavored space cube (i.e., something that astronauts were given to eat on their space missions)? But then again, perhaps not, knowing how bad they were rumored to taste.

Some of the limitations associated with simulating a given environment when restricted to just visual VR are brought home if you imagine how realistic an experience you would get were you to try recreating the experience of dining in a plane, for example. You’d miss the background noise, the lack of air humidity, the lowered cabin pressure (see “Airline Food”). You’d also fail to capture the pressure on your knees when the person in front suddenly decides to recline their seat during the meal service. So it really wouldn’t be the same kind of experience at all now, would it? Vision is undoubtedly important, but without the other sensory cues, it is unlikely to be all that immersive—at least for those more extreme environments that we might want to simulate. I do wonder, though, whether such VR applications might not find a use among elderly patients. Perhaps it could be used to take them back to an earlier time, providing visual cues from the past. After all, playing the music of a bygone era has been shown to help enhance consumption.

Augmented reality dining

Augmented reality involves superimposing artificial visual stimuli over the actual scene. So, for instance, the AR system utilized by my colleague Katsuo Okajima and his colleagues in Japan can update the visual appearance of food or drink in real time. Just imagine: you put on the commercially available headset, and at first you can see the sushi that you ordered on the plate in front of you. Then, simply by moving your hand over the plate (abracadabra-style), the fish suddenly changes from tuna to salmon, say. Move your hand over the plate again, and now it is eel. Not only that but you can pick up what looks like eel sushi and even take a bite without destroying the illusion.

So what’s the point of it, some of you are no doubt wondering. Well, in some of our preliminary research, we have been able to demonstrate that changing how food looks can result in people saying different things about the taste, as well as the perceived texture, of cake, ketchup and sushi. Here, one could perhaps imagine consumers viewing what looks like highly desirable but unhealthy food while actually eating a healthy alternative. And, looking a few years into the future, I can well imagine how we might all end up craving some virtual sushi, when the seas have been fished to extinction and the real thing is nothing but a dim and distant memory (sorry to be so depressing).

One other intriguing example of the intelligent use of AR headsets while dining comes from researchers who have been looking into whether they can trick you into feeling fuller sooner. They aim to do this simply by making the food that you see through the headset (e.g., a biscuit) look larger than it actually is. However, much though I like the idea of AR and VR dining, my best guess is that we are still some years off seeing these headsets at the dining table, even at the world’s most avant-garde restaurants. The limitation here is as much the cost as the fact that it may interfere with the social interaction around a meal.

Have you heard of the “Sound of the Sea”?

To date, the more immediate uptake of digital technology at the dining table has been linked to the personalized delivery of sound, not vision. Here I am thinking of soundscapes and musical compositions, for instance, that the diner or drinker listens to while enjoying a specific dish or drink. In an earlier chapter, we saw how Heston Blumenthal first became interested in the important, if neglected, role of this sense after we gave him a few sonic chips to nibble on in the Crossmodal Research Laboratory. The chef went away and, together with his talented crew in Bray, started to explore different ways of bringing sound to the table, digitally. The first iteration of “sonic cutlery” they came up with was trialed “secretively” for some of the restaurant’s regular clientele, but, unbeknownst to the serving staff who were working the pass, a journalist was sitting incognito in the restaurant that day. When he caught wind of the fact that the diners on the other table had been served a dish that he himself hadn’t had, he immediately summoned the waiting staff over, announced himself and demanded to know what was going on. There was nothing for it but to let him try out the sonic headphones too. The result: a few days later, who should appear staring intently out from the pages of The Sunday Times than that same reporter. The all-new eating utensil for the techno-enhanced twenty-first century had just been “outed.”

Putting the over-ear headphones on tended to mess with the expensive hairdos of a certain section of the clientele, leaving them feeling anything but alluring, and the headphones were unceremoniously withdrawn from service almost as soon as they had been placed on the carefully ironed white tablecloths. It was, as they say, time to go back to the drawing board. Roll the clocks forward a couple of years, and what do those who are lucky enough to have booked themselves a seat at The Duck find? Well, for one of the courses, the waiter arrives at the table holding a plate of seafood in one hand: sashimi resting on a “beach” made of tapioca and bread crumbs with foam. With his other hand, the waiter passes the diner a seashell from which dangles a pair of MP3 earbuds (see Figure 12.3), and encourages the guest to insert the earbuds before they eat. What the diner hears, assuming that he or she does as told,* is the sound of the sea: waves crashing on the beach, a few seagulls flying overhead. Some have found the combination of sound and food to be so powerful they have been brought to tears.

Figure 12.3. The “Sound of the Sea” seafood dish (for a number of years, the signature dish served on the tasting menu at Heston Blumenthal’s Fat Duck restaurant) provides an excellent example of how digital technology can be used to enhance the multisensory dining experience. In research conducted here in Oxford with the chef, we were able to demonstrate that seafood tastes significantly more pleasant (but no more salty) when people listen to waves crashing gently on the beach and seagulls flying overhead than while listening to restaurant cutlery noises or—surprise, surprise—modern jazz!

Since the “Sound of the Sea” dish first appeared on the menu in Bray, a number of other chefs (and even the occasional barista)* have incorporated personalized digital sound into the dishes they serve. For instance, at El Celler de Can Roca, in Girona, part of Spain’s nueva cocina movement, the culinary team created a dessert that came to the table with an MP3 player and loudspeaker. In this case, diners were encouraged to consume their dessert while listening to a football commentator describing Lionel Messi dodging the Real Madrid defenders and scoring Barcelona’s winning goal at the teams’ classic confrontation in the Bernabeu stadium back in 2012. Brilliant! It’s got both high emotion and storytelling, though I bet it tastes better if you are not a fan of the losing team. (And presumably the dish works better if you actually like football.) Meanwhile, the Michelin-starred chefs at Casamia in Bristol sometimes served a picnic basket with an MP3 player that, when opened in the restaurant, would play the sounds of the English summer.

Surprising spoons

There has also been growing interest in delivering sounds digitally from within the diner’s mouth. Chefs, musicians, designers and culinary artists have all become interested in delivering personalized music/soundscapes to accompany specific tasting experiences. Just take, for example, the limited edition Bompas & Parr baked beans spoons, available for £57. Each spoon had an MP3 player hidden inside. If you bought one, you wouldn’t hear anything until you put the spoon into your mouth. Then the sound waves would travel via your teeth and jawbone through to your inner ear. The flavor–music combinations in this case included Cheddar cheese with a rousing bit of Elgar, fiery chili with a Latin samba, blues for the BBQ-flavored beans and Indian sitar music for the curry-flavored beans! While the diner could hear the music, the person sitting next to them would hear nothing. It remains to be seen just how congruent these musical selections were, and whether they really did enhance the flavor of the food.

Meanwhile, over in the Netherlands, Dutch pianist Karin van der Veen has been offering people the chance to taste digital bonbons, De Muziekbonbon. The idea is simple, really, if a little strange. You put the chocolate, which comes with a wire attached, into your mouth, and as you clench the piezoelectric strip (which vibrates when an electric current is passed through it) embedded in the bonbon between your teeth, you can faintly hear the bone-conduced sound of a piano resonating through your jawbone and carrying on all the way to your inner ear.* A pleasant if most unusual experience, as I am sure you can imagine. While I enjoyed my chance to try one of these multisensory treats, it is certainly not something that I can see going “mass market” any time soon. I am just not sure that the increased enjoyment is really worth the effort, at least not once you have done it the first time. It is also rather antisocial, in the sense that all conversation is prevented while the “musical bit” is clenched firmly between your teeth! On the plus side, though, I suppose that you could say that it aids concentration, and hence enhances the experience, nudging the taster toward a more mindful approach to consumption.

Digital flavor delivery

Researchers in Japan have been working to deliver food aromas to match whatever you might see through your AR headset. However, one look at this device (see Figure 12.4) tells you all you need to know about how soon you will be seeing this beauty in the modernist restaurant or gadget store. Never!* As is too often the case, the technology developed to explore the potential connection, or digital interface, with food (or food aromas in this case) fails to consider the aesthetic appeal of their designs. Big mistake!*

Figure 12.4. Hmmm, tasty! Sometimes I worry that human–computer interaction (HCI for short) researchers may spend a little too much of their time thinking about what is possible at the intersection between technology and food and perhaps not enough time considering what is actually likely to be applicable or even desirable out there in the real world. Even the most innovative modernist chef would, I presume, balk at the idea of having their diners put one of these devices on. And there we were, thinking that over-ear headphones were intrusive!

The more plausible mainstream delivery of food scents will, I believe, come from plug-ins, like Scentee. This has already been used for one marketing-led intervention in the U.S., namely, the Oscar Meyer bacon-scented alarm clock app. You simply insert a small plug-in device to your mobile and set the time, and you will be woken up by the sound of sizzling bacon and the matching smell! Meanwhile, in Spain, top chef Andoni has been using digital scent delivery to extend the interaction with his diners; those who have booked a visit to Mugaritz can get to experience the actions, aromas and sounds that accompany one of the more multisensory of the dishes on the tasting menu in advance by downloading the appropriate app (see Figure 12.5). On making a circular motion to virtually grind the spices that are visible on the screen of their mobile device, the user not only hears the sound of mortar on pestle but also gets a blast of spicy aroma up their nostrils (via the scent-enabled plug-in). These are exactly the same actions, sounds and aromas that they will subsequently experience on tasting the dish itself while they are sitting in the restaurant. One of the aims is to use multisensory stimulation in order to help build up anticipation in the mind of the diner prior to their arrival at the restaurant. Who knows, the expectant diner may even start to salivate.

However, while such digital smell delivery is certainly practical, the fundamental problem is whether anyone is going to buy the refill. This, in a way, contributed to the demise of DigiScents (a digital smell delivery company started during the internet boom years) a couple of decades ago (and at no small expense to investors, it should be said). My best guess is that, while the technology works, there isn’t really any consumer desire, or need, for such digital innovation just yet. And without that, these dreams of digital smell are likely to fail, just like those previous attempts.

Figure 12.5. A scent-enabled app helping to build anticipation in the mind of the diner booked into the Mugaritz restaurant in Spain.

How would you fancy eating with a vibrating fork?

As we saw back in the “Touch” chapter, the world of cutlery design is set for a revolution. Part of the change will come from the introduction of new forms, materials and textures for cutlery, but another strand of future development may well revolve around the emergence of digitized, or augmented, eating utensils. For, at least according to the human–computer interaction community, this may also radically transform the way in which we will interact with our food in the years to come. Just imagine a fork that vibrates to let you know that you are gobbling your food a little too fast! No, really! (See Figure 12.6.)

Figure 12.6. One of the ways in which digital technology could make its way on to your dining table in the future. This is an early prototype of the HAPIfork, a Japanese gadget designed to modify our eating behavior.

Perhaps the most interesting example of digitally augmented cutlery goes by the name of Gravitamine. This utensil cleverly creates the illusion of weight in the hands of its users. Given what we saw in the “Touch” chapter, I can well imagine how such a digital solution would enhance the diner’s meal experience. Though you could be forgiven for wondering whether it wouldn’t be more convenient to invest in some genuinely heavy cutlery instead of having to recharge it on a regular basis. One other market where digitally enhanced cutlery may have a promising future is for those patients who find it difficult to control their hand movements—sufferers of Parkinson’s disease, for instance, whose tremors can lead to food spillage. In fact, one innovative company has already come out with some anti-shake cutlery to help combat this particular problem.

Electric taste

Researchers can now deliver rudimentary taste sensations simply by electrocuting your tongue in the right way. Any volunteers? Come on now, it isn’t as unpleasant as it sounds. Sadly, though, it isn’t anything like as pleasurable as many of the press reports would have you believe either! According to some journalists, this all-new approach holds the promise of a never-ending sequence of flavors delivered by your digital device. All you need is a power supply and a stimulator pressed against your tongue. Indeed, the world’s press went wild when researchers recently launched a digital lollipop. But hold on a minute, not so fast. The first question to ask before taking all the hype at face value is whether those who are writing about it have actually experienced electric taste for themselves. Too often, this would appear not to be the case! Instead, it seems that much of the time they are relying on second-hand reports by those who are promoting these devices.

I have tried some of these devices, and found the experience to be disappointing, to say the least. Now, perhaps I am just unlucky, since electric taste works better on some people’s tongues than on others. However, even this approach’s most ardent advocates admit that it is easier to get sour and metallic taste sensations than it is to get salty and umami . . . and sweetness—well, that is a real challenge. Thus the palate of digital tastes that one has to work with, even in the best-case scenario, is actually pretty limited, and that’s for those in whom electrical stimulation of the tongue works well. I have little faith that things will improve much, experientially speaking, when the electrical stimulation device is embedded in the end of a spoon or in a piece of digital cutlery or glassware.

But more importantly, even if all taste sensations could be rendered perfectly, you would still be left with a very thin dining experience. For anyone who has evaluated a weak pure tastant in solution will know only too well how unsatisfactory it is, even in the best of cases. And as we saw in the chapter on “Smell,” taste constitutes only a very small part of our multisensory flavor experiences anyway; all those fruity, floral, meaty, herbal notes that we enjoy while eating and drinking really come from the nose. In other words, you could never hope to evoke them by electrocuting anyone’s taste buds. You should be electrocuting their nostrils instead (or as well)—likely to be an unpleasant, complicated and possibly even painful procedure.

While the original aim of those developing digital taste was to remove the need to deliver an actual tastant, the approach that is now being developed involves augmented tasting. Some researchers, for instance, have been looking at what would happen if your tongue is zapped while you are looking at a tasty meal, say, or even while eating or drinking something real. It turns out that the hedonic response to electric taste was indeed changed when people were looking at gastroporn. Similarly, there is evidence to suggest that people’s response to real food and beverage items can be modified by presenting electrical taste at the same time. So, if diners were given salty sensations electrically while eating, would this mean that they wouldn’t have to add so much salt? This was the conceit of the “No Salt Restaurant,” a two-day pop-up in Tokyo. Diners got to eat with an Electro Fork, capable, apparently, of delivering some electrical seasoning. As a trial run, the restaurant offered a five-course saltless menu of salad, pork cutlets, fried rice, meatloaf and cake. My guess is that not many people would have wanted to repeat the experience.

Is this more about marketing than genuine health innovation? One important thing to bear in mind is that the role of salt isn’t solely as a taste enhancer. It also plays a key role in determining food texture/structure, and that is something that electric taste simply cannot help with. One further problem with this technology is that our brains seem exquisitely sensitive to how the sensation elicited by different compounds changes over time. This is part of the reason why, for instance, you can distinguish sugar from other artificial sweeteners like aspartame (because the taste sensation ramps up much sooner in one case than the other, and may well linger for longer too). So unless you can get the time-course of sensation associated with electrical taste right, the experience is never going to be as good as “the real thing.”

Digital technologies changing the food landscape

Go online nowadays and you can find all manner of apps that promise to provide assistance no matter what you want to know about or do to/with your food or drink. Switched-on celebrity chefs and lifestyle bloggers are only too willing to advise you what you should be eating, or else help you to prepare a new dish. This is, after all, big business these days. There are also a growing number of smartphone apps that can interface with, and thus control, various kitchen devices. Just take the “Bright Grill” as one representative example, an electric barbecue with an app that will alert you as soon as your sausages are cooked perfectly, even if you are away from the grill, so that hopefully you won’t end up cremating them, as usual. Don’t such inventions make you wonder how we all managed in the good old pre-app days?

In fact, you can find pretty much anything you want at the app store nowadays.* Believe it or not, there is even one called the Egg-Calculator, brought out by ChefSteps. (This is one for all those of you who are addicted to “yolk porn” (see “Sight”); it contains more “protein in motion” shots than even the most ardent food junkie needs to get off on.) Using this app, there is no longer any excuse for your slow-cooked egg to turn out any other way than exactly how you wanted it. Meanwhile, there are now many price comparison apps that enable the savvy diner to scan their menu and compare how much the same item would cost at other restaurants. On occasion, in big cities like New York, you can find exactly the same bottle of wine being priced at four times what you would pay at another restaurant just down the block. Wouldn’t you want to know when you were paying through the nose?

The clever folk at Google have even come up with an app to help restaurant diners split the bill, though the audience for this app is presumably declining somewhat given that more and more of us are dining out alone these days (see “Social Dining”). And one does have to wonder whether a simple calculator wouldn’t do just as well. Interestingly, aware that picking up the hefty tab at a fancy restaurant can put something of a downer on the meal experience of the person paying, and mindful of the fact that the end of an experience tends to be particularly memorable, some high-end restaurants now get their diners to part-pay for the meal in advance, so that the pain at the end isn’t quite so bad. That is what I call intelligent design!

Another interesting development involves those sensory apps that allow you to access digital content by scanning the label of anything from a tub of Häagen-Dazs ice cream to a bottle of Krug champagne. For instance, the Concerto app was designed to help the consumer pass the time after taking their ice cream out of the freezer before serving. Customers get their mobile device out and scan the QR code (that black and white patterned square on the lid of special packs), and the next thing you know musicians can be seen and heard “magically” floating on top of the Häagen-Dazs. Each of the musical selections lasts for about two minutes—i.e., just long enough for the contents to soften slightly, according to the marketing blurb. Once the music draws to a close, the ice cream should be ready to serve.

There are other “clever” apps that claim to be able to count the calories in a dish by analyzing the picture you take of it, and many other new food-related technologies are in development. One project, funded by Philips Research, investigated the feasibility of having people eat from plates that have digital scales embedded in them, in order to calculate the total amount of food that they had eaten. Google’s AI, called Im2Calories, is also training itself to count the calories in food photos. It is already accurate to within 20%. But do you really want your technology to keep track of what you eat? What, every gram (or calorie) of it? Furthermore, it remains to be seen quite how accurate these devices really are. After all, the visual system, and the brain that supports it, have been fine-tuned over the course of human history to rapidly assess the energetic content of foods. This is precisely the sort of thing that our brain evolved for, and the evidence suggests that we manage to evaluate nutritive food sources in little more than the blink of the eye. However, even this fine bit of tackle sometimes gets it wrong, or at least our conscious minds do! So why expect the technology to do a better job?

Do robot cooks make good chefs?

But to end, let’s return to the question with which we started this chapter: what would you think if you found out that your dinner had been cooked by a robot chef? On the one hand, this should be a wonderful example of precision cooking. That is what we all want, isn’t it? Exactly the same taste time after time? And yet, if the food or drink is made by machine, why bother going out to eat in the first place? Why not simply buy it from a packet straight from the production line, as sold in the supermarket? But while the idea of a robot chef, cocktail maker, waiter or even dishwasher might sound completely futuristic, the truth is that the future is already here. For instance, at the Robot Restaurant in Harbin, China, twenty robots, each costing £20–30,000, work the kitchens and restaurant floor. They cook the dumplings and noodles, and wait tables too (see Figure 12.7), though they do need recharging every five hours or so. And KFC recently introduced a robot-serviced restaurant in China. Meanwhile, Royal Caribbean International teamed up with Makr Shakr to create the world’s first “bionic bar” (i.e., a robot cocktail maker) aboard the newest addition to its fleet, the Quantum of the Seas. Here’s a description of what those who have booked a berth can look forward to while they are out at sea: “Guests can place drinks orders via tablets and then watch robotic bartenders mix their cocktails. Each robot can produce one drink per minute and up to 1,000 drinks per day, according to Royal Caribbean.”

Figure 12.7. Will robot chefs be making our dinner in the future?

I was recently approached by the start-up Momentum Machines, who are about to roll out the first robot line/short order chef for mainstream restaurant kitchens. They wanted to know what people would think about food if they knew that it had been prepared by a robot. Would they like it more, or would they perhaps be put off? Do diners really care who makes their food, or are they instead just interested in the taste of the final product? My suspicion is that people will rate food and drink differently (and if I had to guess, less positively) if they are told that it has been created by a robot rather than a real person. As far as I can see, the real sticking point here is likely to be that robots don’t have very good tasting abilities. Consequently, such machines will do better when working with packaged (i.e., standardized) ingredients rather than with fresh produce whose quality/ripeness may vary. I also suspect there is something about the predictability of robot-cooking that makes it less appealing than when a real person does all the work.

For better or for worse, then, there really can be little doubting that our future dinners will become increasingly intertwined with digital technologies. This is the case even at home. Indeed, for the home market, Moley Robotics’ home-cooking chef should be available early in 2018 for around £50,000. I can just see my wife’s eyes lighting up at the prospect.