2. Smell

Think about the last time you had a head cold and your nose was blocked. Food and drink didn’t have much of a taste, did they? Ever wonder why that is? What is missing in such circumstances is not taste—trust me, your taste buds are working just fine—but rather aroma. Assuming that you don’t have a cold at the moment, try holding your nose pinched tightly closed, and get a friend to feed you something without letting you know what it is. Unless they pick something really pungent (and if they do that, maybe they aren’t such a good friend after all), you will most likely have very little idea of what you are tasting—onion or apple, red wine or cold coffee. These pairings are surprisingly hard to tell apart without a functioning sense of smell.*

It is important to distinguish here between the two different ways in which we smell. There is the “orthonasal” route: when we sniff external aromas from the environment. And there is “retronasal” smell: when volatile aromatic odor molecules are pulsed out of the back of the mouth into the back of the nose whenever we swallow while eating and drinking. The orthonasal sniffing of food aromas is especially important because it allows us or, rather, our brains to form the rich flavor expectations concerning both what the experience of tasting will be like and how much we expect to enjoy it. But it is the retronasal perception of aroma, on swallowing, that really provides our tasting experiences with their rich variety and interest. Most of the time, though, we remain acutely unaware of how much of the information that we think we are tasting via the tongue comes in via the retronasal olfactory route. This is, in large part, because food aromas are experienced as if coming from the mouth—as if being sensed by the tongue itself. This strange phenomenon goes by the name of “oral referral.”

To illustrate the point, try eating a jelly bean with your nose closed between thumb and forefinger. What can you taste? You will most likely experience sweetness, maybe some sourness and, who knows, perhaps a hint of spiciness too (at least if you get a cinnamon one). Then, after a few bites, let go of your nostrils. You will suddenly get the fruity flavor, orange or cherry, etc. But you will experience that flavor as coming from your mouth, not from your nostrils. That is oral referral in action, the mislocalization of aroma to the mouth!

Does vanilla smell sweet to you?

The answer for most people is a definite yes. People give exactly the same answer when it comes to the aroma of caramel and strawberries too. Now, this is confusing, right? After all, didn’t I just say in the last chapter that “sweet” was a taste descriptor? So how can an aroma be said to smell sweet? Some have argued, I think wrongly, that this is a kind of synaesthesia. Interestingly, food companies add vanilla flavoring to ice cream to bring out the sweetness. They do this because at very cold temperatures your taste buds don’t work so well, and hence you can no longer taste sweetness—but you can still smell it. Surely you have had the experience of drinking a warm glass of cola by mistake? Doesn’t it suddenly taste sickly sweet? The composition of the drink itself hasn’t changed, but the signals that your taste buds send through to your brain have changed as a function of the drink’s temperature. Since the drink is usually served cold, the manufacturer has added some sweetness through the nose. Confused? You should be.

In the other direction, i.e., when it comes to taste’s influence on aroma and flavor perception, things are very different. One of the classic studies in this area involved people tasting a solution whose sweetness had been carefully calibrated to be just below the level of awareness (in other words, it tasted like plain water). Nevertheless, when people held a small amount of that subjectively tasteless liquid in their mouth, their ability to detect the cherry-almond aroma in another drink that they were smelling suddenly increased dramatically. Importantly, however, further research showed that the taste had to be congruent with the smell in order for this effect to occur. Adding a sub-threshold dose of monosodium glutamate into the mouths of Western participants didn’t have the same effect. However, the response may well be different in Japanese consumers. In other words, the research suggests that while everyone’s brain uses the same rules to combine the senses, which particular combination of tastes and smells gives rise to the enhancement or suppression of flavor depends on the food culture that person has grown up in.

The amazing thing is how quickly this kind of learning happens, and what’s more it continues to occur throughout our lifetimes. Take a novel odorant, the smell of water chestnut (as in one study conducted on Australian adults a few years ago). Then, simply pair it with either a sweet or bitter tastant in the mouth. Believe it or not, after no more than three co-exposures, the smell starts to take on the appropriate taste qualities. More remarkably still, this can occur even when the tastant is presented at a level below perceptual awareness.

Have you ever noticed how freshly ground coffee often smells wonderful, yet when you come to taste it the flavor can be a little disappointing? The same thing in reverse occurs if you take a ripe French cheese. It may well smell like the inside of a jock’s training shoe (please excuse the metaphor), yet if you can manage to put some in your mouth, the pleasurable experience that follows is often sublime. What is happening? These changes in our hedonic ratings—basically, how much we like something—illustrate the distinction between our two ways of smelling: orthonasal (when breathing in) and retronasal (when breathing out through the back of the nose). Normally, we are remarkably good at predicting the likely retronasal flavor of a food based on nothing more than an orthonasal sniff. So good, in fact, that we simply don’t know we’re doing it.

Scenting the scene

Look around the world of high-end modernist cuisine and molecular mixology and one sees an increasing use of scene-setting scents and mood-inducing aromas. These are being added to dishes, to drinks, to the dining table and even, on occasion, to the entire dining room (especially in those situations where the chef has the luxury of serving a single sitting, with everyone eating the same course at the same time). The aim in many cases is to create a particular atmosphere or mood, or else to trigger a specific memory in the mind of the guest, no matter what they happen to be consuming. For example, Heston Blumenthal serves a moss-scented “Jelly of Quail with Langoustine Cream and Oak Moss” dish at his flagship restaurant, The Fat Duck. Steaming scented vapor pours out from the moss-scented carpet placed in the center of the table (see Figure 2.1). No one, I presume, starts salivating at the thought of a mouthful of the green stuff and yet the theatrical use of scent definitely helps transport the diner to another place and in so doing enhances their experience of the dish. At Alinea in Chicago, hot water is poured over a bowl of flowers when the “Wild Turbot, Shellfish, Water Chestnuts, and Hyacinth Vapor” dish is served. The chef, Grant Achatz, is also famous for his pheasant, served with shallot, and cider gel, which is accompanied by burning oak leaves. The idea here is to use scent to trigger happy memories of an autumnal day from childhood.

Figure 2.1. One of the fragrant dishes served at The Fat Duck. The scent of moss covers the table and fills the diners’ nostrils.

Of course, one has to be careful not to overuse scene-setting scents. One diner, writing on TripAdvisor about their experience at The Fat Duck, stated: “The final dish was ‘Going to Bed’ [‘Counting Sheep’] and I think was meant to be reminiscent of being a baby, but the smell of baby talc was overwhelming and that’s not an aroma one necessarily wants while eating.” While this was certainly not my recollection of the dish, the quote does highlight the potential danger for anyone trying to use a background scent that may compete with the foreground aromas of the food itself. The challenge is, in part, made worse by the fact that even ambient smells can be mislocalized to the oral cavity and experienced as tastes or flavors in the mouth if one is not careful. (Yes, oral referral strikes again!)

Fortunately, the gastrophysicist has a few tips up his sleeve to show the modernist chef/molecular mixologist how best to convince their customer’s brain to segregate the background environmental smell from the foreground aroma of the food and drink (assuming, of course, that that is what the chef is trying to do). Ensuring that the various smells are first encountered at different points in time will help here, as this will make it easier for the customer’s brain to localize the background aroma in something other than the food or drink. And presumably Achatz keeps his oak leaves and hyacinths very visible in order to do the same. Crucially, by using such an approach, the perceived source of the scent is likely going to be correctly localized in something other than the food.

I would like you to imagine that a sugar cube is soaked in a few drops of rose oil and placed into a glass of champagne. Imagine the drink sitting in front of you, effervescing gently. The fragrant smell of an English rose garden emanating from the glass surrounds you. Before you know it, you find yourself being transported to a pleasant scent-infused summer afternoon somewhere in your memory. This is exactly what top mixologist Tony Conigliaro, of 69 Colbrooke Row, wants you to experience.

Conigliaro is using scent to prime positive memories and associations. One of the specific advantages of this approach is that smell has a much closer, more direct connection with the emotional and memory circuits in our brain than any of our other senses. It turns out that the olfactory receptors in our nose are actually an extension of our brain. In fact, it is only a couple of synapses from the cells in the olfactory epithelium lining the inside of the nose through to the limbic system, the part of the brain that controls our emotions. By contrast, information from the other senses has a much longer path to travel through the brain before it hits the emotion centers, and hence it can be more easily filtered out. The challenge, though, for a multi-course, smell-enhanced tasting menu is how to clear one fragrance out before the next course arrives, one of the key practical problems that eventually scuppered early attempts at scented cinema—remember Smell-O-Vision, anyone?

If smell is indeed such an important part of what we taste, and if it is such an effective means of triggering our moods, emotions and memories, then any one of the innovative approaches mentioned thus far in this chapter really makes sense from the gastrophysics perspective. However, those of you who are not lucky enough to eat or drink at one of these gastronomic hotspots might be thinking: how exactly am I supposed to use this knowledge? In the next section, I want to share some of the intriguing ways in which we will all be exposed to this new world of augmented flavors in the coming years. For where the modernist chefs, molecular mixologists and culinary designers lead, you can be sure that food and beverage manufacturers are never far behind.

Making sense of smell

Given how important smell is to our enjoyment of food and drink, it is surprising to realize quite how many of our everyday food—and especially beverage—experiences are not optimized to deliver the best orthonasal aroma hit. Perhaps the best (or should that be worst?) example of poor olfactory design are those plastic lids that are routinely placed over millions of paper cups of hot coffee. While these lids undoubtedly allow you to drink without having to worry about spillage, what they singularly fail to do is to allow the drinker to appreciate the orthonasal aroma of the cups’ contents by sniffing them. This is especially unfortunate in the case of a freshly ground cup of coffee, given that it is one of the most universally liked smells. Much the same problem occurs whenever we drink directly from a bottle or can (uncouth as it may be!). Once again, it is the orthonasal olfactory hit that is mostly missing from the experience. We can either sniff the contents or we can drink them, but there is simply no way that we can do both at the same time, no matter how hard we try. And drinking through a straw—well, that is even worse!

So, having identified the problem, what can be done about it? In terms of design, there are a number of simple solutions out there. They include the reshaping of the lid, or adding a second opening to allow the coffee (or tea) lover to sniff the aroma of their favourite beverage while sipping. This is part of the innovative solution incorporated into the ergonomic lid introduced by Viora Ltd. Their novel design allows the consumer to smell their coffee without having to take the lid off. Common sense, really. But if that’s the case, you have to ask yourself why it took so long for someone to come up with this solution. My suspicion is that it is all down to oral referral again. It’s not obvious that retronasal smell is involved in tasting, and hence no one bothers to factor it into their designs.

Another intriguing solution comes from Crown Packaging. The company designed a can (see Figure 2.2) with a top that lifts off completely, allowing the thirsty consumer to see and, perhaps more importantly, sniff the contents more easily than when drinking from a traditional can (i.e., one with a small tear-shaped opening).

At the opposite extreme to the traditional lid, bottle or can that resolutely prevents the consumer from orthonasally enjoying the aroma of whatever it is that they are drinking, let’s take the humble pint. Back in the day, when all lager beers used to taste the same, the lack of any protected headspace over the drink in the glass probably didn’t matter much. However, given the revolution in craft beer in recent decades, there are now a host of drinks out there that many of us are willing to pay a hefty premium for (because, for a change, they really do taste of something). The problem with the traditional pint glass filled (as it always is) to the rim is the lack of any protected headspace over the beer in the glass. This, in turn, means that there is no way of concentrating the drink’s aromas. So, assuming we take it as read that a more intense smell is a good thing, perhaps we should be thinking again about the design of the glass in which so many pints of beer are served every day as well. So what, one might ask, would the gastrophysicist recommend here?

Figure 2.2. Two examples of enhanced olfactory design: the Viora lid (left) and Crown’s 360End™ can (right).

You might start by considering what happens in the world of wine. After all, there is always around ten times more research into wine than into anything else that we might be tempted to drink (presumably because researchers like drinking wine). Firstly, notice how wine glasses are never filled to the rim. Somebody out there certainly believes, rightly or wrongly, that the empty headspace over the drink is important. It is meant to help preserve the aroma and bouquet of the contents of the glass, so as to delight the taster’s nostrils. In fact, the better the wine, the larger the proportion of the glass that is left empty, or at least so it would seem.

One might, of course, argue that having a full pint glass doesn’t really matter; after all, as soon as the thirsty drinker has taken a few draughts from their pint, won’t they have created an aromatic headspace over the drink anyway, so why worry? Bear in mind, though, that more often than not the initial sniff will set up expectations about what’s coming next. It is these expectations that end up anchoring, and hence disproportionately influencing, the tasting experience that follows. Isn’t that first mouthful so much more important (not to mention more enjoyable) than any of the swigs you take in the middle of your pint? And both have got to be better than the last mouthful, when all you are left with are the warm flat dregs in the bottom of the glass. So, if we value the flavor and aroma—as we should—then maybe we should all make sure a little room is left in the glass when the beer is first served.

Figure 2.3. Lidded stein glass: an early example of intelligent olfactory design?

Of course, the danger is that the average beer drinker has become so accustomed to seeing their glass filled to the brim that they might feel short-changed were they to be given anything less. An alternative solution to this olfactory problem might well simply be to dust off those old stein glasses that once came with their very own lid attached (see Figure 2.3). The purpose, at least according to one early commentator, writing back in 1886, was to protect the gases released from the beer’s surface. I like to think of this as clever olfactory design from 130 years ago!

How can the delivery of flavor be enhanced?

Have you ever noticed how little aroma there is in the public areas in airports? Walk into a railway station or book store and your nostrils will almost certainly be assaulted by the smell of coffee. Airports, by contrast, appear to be olfactorily neutral spaces. That said, next time you pass through London Heathrow Airport’s Terminal 2, why not stop for a bite to eat at The Perfectionist’s Café. If you do get the chance, then I’d recommend the fish and chips. What may surprise you about the dish is the use of an atomizer to dispense the aroma of vinegar. This, as we will see below, is just one of the ways in which creative individuals are starting to change how the more aromatic elements in a dish are delivered to the table.

Over the last couple of years, London-based chef Jozef Youssef has been experimenting with the atomized delivery of aroma in a number of the dishes he serves. During his “Elements” dinners, for instance, the mossy-earthy smell of geosmin was sprayed over each and every diner’s bowl of leek consommé, leek ash and goat’s cheese cream. Meanwhile, in the chef’s sell-out “Synaesthesia” dining events, it was the scent of saffron (saffranel) that was sprayed over a butter-poached lobster with white miso velouté instead. Sounds simple, right? So, why don’t you try this for yourself (i.e., “atomizing” your guests) the next time you invite them over for dinner? You never know, do it right and they may just thank you for the way their senses are awakened and for how much better their food tastes as a result. All you need is a small, clean spray bottle in which to place your “food perfume.”

It is F. T. Marinetti and the Italian Futurists, though, who really deserve the credit for first bringing atomizers to the dining table, back in the early decades of the twentieth century. Though they were more likely to spray perfume (smelling of carnations) into their diners’ faces should any of them be foolish enough to look up from their plates while eating. Quite what effect this had on the multisensory tasting experience has sadly not been recorded for posterity! But the Futurists were much more about provocation than about delivering the best multisensory dining experience possible.

Today, inventive chefs and mixologists are using smoking guns to deliver the requisite aromas to the dishes and drinks they serve (see Figure 2.4). The dry-ice-based cloud pourer allows the creative flavorist to add concentrated aromas to a dish or drink in the form of a misty vapor that can be poured tableside, or at the bar, right in front of the wide-eyed and open-mouthed customer. Come on now, don’t be afraid . . .

Figure 2.4. A smoking gun—the chef’s best friend?

You might also not have realized that aromatic packaging has been in the marketplace for years. Just take the humble chocolate ice cream bar. While everyone loves the smell of chocolate, the real stuff lacks its delicious aroma when frozen. One manufacturer even tried adding a little synthetic chocolate aroma to the glue seal of the packaging to make up for the lost smell, so that when the customer ripped open the packaging they caught a whiff of chocolate smell which they, naturally enough, assumed must have come from the chocolate covering the ice cream itself. Not everyone uses scent-enabled packaging solutions, that’s for sure. Truth be told, it can be tricky to deliver an authentic-smelling encapsulated chocolate aroma.

Then, of course, there are the reports of coffee companies injecting various aromatic substances (some, so the probably apocryphal stories go, extracted from the rear end of the skunk) into the headspace of their packaged coffee. This presumably helps to explain why the experience so many of us have on first opening a packet of coffee can be so great. Your nostrils get a sharp and pungent hit of what you undoubtedly thought was great-smelling freshly ground coffee. But why, you should ask, is the experience nearly always disappointing when the container is opened again subsequently?

Another intriguing example of how design can be used to modify flavor came with the launch of The Right Cup in 2016. This glass drinking vessel includes a colorful sleeve that gives off a fruity aroma. The apple-flavored cup is bright green, the lemon yellow, and the orange—well, what else but orange-colored? The idea of the cup is that the consumer can drink water from it and have a tasting experience that approximates to what might be expected on actually drinking the appropriate fruit juice, or at least fruit-flavored water. I bet that the color cue provided by the sleeve will turn out to be pretty important to the tasting experience. Along somewhat similar lines, in 2013, PepsiCo applied for a patent for the use of encapsulated aroma in their drinks packaging. These scented capsules would only be broken, and the aroma released, when the consumer unscrewed the lid. The thinking was that a better aroma experience could be delivered by scenting the packaging rather than the product itself.

Canadian company Molecule-R sells an Aromafork kit: for around U.S.$50, you get a set of four metal forks, with a bag of circular blotting papers to insert into the end of the fork, and twenty small vials of different aromas intended to augment the flavor of food with each and every mouthful. I have yet to try The Right Cup, but my experience with the Aromafork is that unless one is very careful the aroma can all too easily end up striking one as synthetic. This was certainly the response of the guests on the BBC Radio 4 show The Kitchen Cabinet when I tried the scent-enabled fork on them. This is not to say that we can always distinguish synthetic from natural aromas; more often than not, we can’t. The problem here is just that many of the aromas that are currently sold with the kit smell cheap and artificial, and most of us certainly don’t like our food to taste artificial.

I remain to be convinced by Molecule-R’s suggestion that their innovative fork is ideal for the home chef who has forgotten to add a particular ingredient to a dish. Its most beneficial use, as far as I can see, would be to replace some particularly expensive ingredient. I can, for example, imagine dribbling a few drops of quality truffle oil, say, on to my fork, thus delivering far more culinary pleasure than if the same amount of oil were simply to be drizzled haphazardly over the food itself. The atomized scent of saffranel could be used in much the same way—saffron being, it is said, gram for gram, more expensive than gold. So are you game to try this at home? Simply put a few drops of something fragrant on to the middle of a wooden spoon or fork before using it to serve your guests. You’ll be guaranteed to deliver a dining experience with a difference!

Slow food this most definitely is not. But should the consumer realize that they can get a better experience, or else the same flavor, at a fraction of the price (at least in the case of truffle, saffron and other similarly expensive ingredients), then who knows, the Aromafork—or some more aesthetically pleasing successor—might just revolutionize how we eat in years to come.*

Ultimately, the chances of such augmented approaches succeeding in the long term are going to depend on the delivery of quality scents at a reasonable price. Remember the perceived synthetic (rather than natural) nature of the scents in the Aromafork. Once the sniffer realizes that what they are sniffing doesn’t originate from their food or drink but instead comes from the cutlery, glassware or packaging, they might well start to believe that it smells artificial. Rightly or wrongly, there are frequent scares about our exposure to synthetic flavors and scents in everything from fragranced candles through to processed foods. It is that belief or concern that the smell is artificial or “chemical”—though, of course, all aromas are chemical—as much as the evidence before our nostrils that will, I predict, reduce hedonic ratings when sampling these products.

Have you noticed how often the modernist chef stresses, either explicitly or otherwise, the natural origins of their off-the-plate aromas? Be it the scent that is released when hot water is poured over the hyacinths at Alinea, or the recently deceased Homaro Cantu’s use of fresh sprigs of herbs in the curly handles of his cutlery at Moto, also in Chicago. We will just have to wait and see how the consumer of tomorrow responds to this all-new world of olfactorily enhanced food and beverage packaging, glassware and cutlery. No doubt the food and beverage companies, together with the flavor houses, will take a page out of the chefs’ and mixologists’ book, and figure out how best to emphasize the naturalness of their novel olfactorily enhanced design solutions.

The olfactory dinner party

So far, we have focused on the use of scent to deliver both food and non-food aromas in a more effective manner, so as to enhance the multisensory flavor experience, or else to provoke a certain mood, memory or emotion. But can flavorful smells also be used to promote healthier eating behaviors? Go back to the 1930s and one finds the Italian Futurists (yes, them again) suggesting that “in the ideal Futuristic meal, served dishes will be passed beneath the nose of the diner in order to excite his curiosity or to provide a suitable contrast, and such supplementary courses will not be eaten at all.” The same notion makes an appearance in Evelyn Waugh’s 1930 novel Vile Bodies: “He lay back for a little in his bed thinking about the smells of food, of the greasy horror of fried fish and the deeply moving smell that came from it; of the intoxicating breath of bakeries and the dullness of buns . . . He planned dinners, of enchanting aromatic foods that should be carried under the nose, snuffed and then thrown to the dogs . . . endless dinners, in which one could alternate flavour with flavour from sunset to dawn without satiety, while one breathed great draughts of the bouquet of old brandy . . .”

Smell (olfaction), then, is more important to our tasting experiences than any of us realize. That being the case, you might be thinking, why not simply enjoy the aromas of great-tasting food without the calories associated with actual consumption? That, at least, is one of the ideas behind the olfactory dinner party. However, you don’t need a gastrophysicist to tell you that your cravings are never really going to be satisfied by smell alone.

And yet there are a growing number of companies out there who are starting to deliver food aroma as an end in itself. Just take the coffee inhaler: wherever you might be, you can get a caffeine hit without having to find a coffee shop. You can inhale chocolate aroma too. Culinary artists Sam Bompas and Harry Parr fit right in here, with their “Alcoholic Architecture” installations. These U.K.-based jelly-mongers have experimented with a series of “cloud bar” installations, where punters could spend fifteen minutes or so in a space infused with a gin & tonic mist. Then there is the Vaportini, a bit of kit that gently heats your drink and concentrates the aromas, so that you can just inhale them and supposedly enhance your experience as a result.

This all sounds intriguing enough, but I really don’t see the idea of the olfactory dinner party gaining popularity any time soon. For I doubt that our brains can be truly satisfied without our actually consuming something. As Lockhart Steele, owner/creator of Eater.com puts it: “Novelty is everything in a certain corner of the dining world, no matter how fleeting . . . Dining in the dark, dining without talking—all that’s left is eating without eating.” And as we will see in the “Touch” chapter, oral-somatosensory (i.e., mouth touch) and gustatory (or taste) stimulation appear key to driving our brains toward satiation (i.e., fullness).

That is not to say that enhancing the delivery of food aromas while actually eating and drinking (what I am calling “augmented flavor”) might not be a good idea. The female participants in one recent laboratory study became fuller sooner following the enhanced delivery of food aroma while they were eating a tomato soup. In this case, simply ramping up the olfactory component of the dish reduced people’s consumption by almost 10%. Thus, all of us might be able to reach satiety sooner if only we knew how to stimulate our senses more effectively. Such findings support the idea that augmenting the orthonasal aroma of food and drink could (say, through food and beverage packaging or via smelly cutlery) lead to greater enjoyment, not to mention possibly smaller waistlines.

Scents and sensibility

Have you been to a Hilton Doubletree hotel recently? If so, you will no doubt be familiar with the deliciously sweet and aromatic cookie scent that fills the lobby at check-in. Smile at the person behind the counter and they are likely to give you a freshly baked cookie. Once again, we see a desirable food aroma being combined with an unexpected (at least on a first visit) gift. Definitely a good idea from the sensory marketing perspective. I must confess that I am a regular visitor, and I can’t help but worry that my exposure to the high-energy sweet food scent encourages me to consume a cookie that I might otherwise not have eaten.

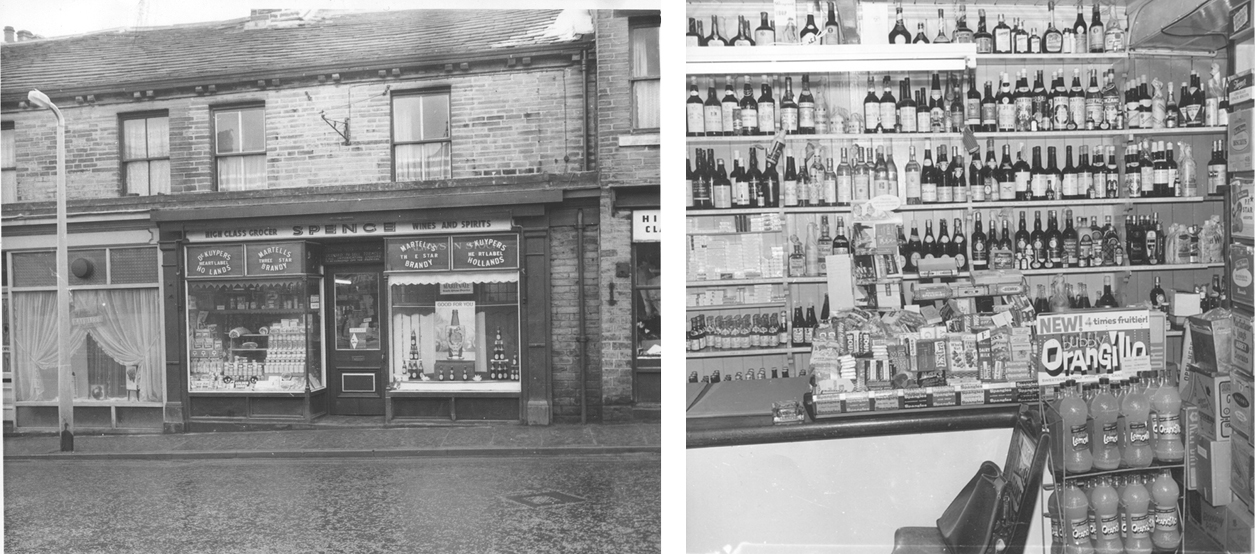

My grandfather, who had a grocer’s shop in the north of England, would sprinkle quality coffee beans behind the counter (see Figure 2.5). When a customer came into the shop he would crush the beans underfoot, releasing the coffee aroma that would hopefully nudge them into buying some of the real stuff. So, given what I have just told you, you will understand why it does not come as any surprise to me to see food stores now releasing the enticing scent of their products in order to try to lure customers in. But is all this scent-based marketing actually provoking our desire to eat in many situations where we might not otherwise have thought about consumption?

Figure 2.5. My grandfather’s shop in Idle, Bradford, where olfactory sensory marketing was being used intuitively half a century ago.

We really do need to be more aware of the consequences of the looming commercialization of food-based scent and flavor marketing. Those exposed to food aromas exhibit an increased appetite not only for any food that happens to be associated with that specific aroma but also for other foods and beverages that are similar in terms of their macronutrient profile. That is, exposure to one sweet high-energy food leads to our appetite for other foods with a similar aroma increasing. Have you noticed how food chains tend to locate their stores in those positions in a mall that ensure the optimal dispersion of their signature smell, and often combine this strategy with the use of the least effective extractor fan permitted, so that more of the aroma hits the consumer’s nostrils.

Let me leave you for now, though, with an even scarier thought. Have you ever considered what is going to happen when food runs out as a result of global warming, overfishing and food blights? Well, artists Miriam Simun and Miriam Songster have imagined how three foods that are currently threatened, namely chocolate, cod and peanut butter, might be enjoyed in the future. To illustrate their take on the future, they drove The Ghost Food Truck from Philadelphia to New York in 2013. Those who visited this most unusual piece were given a mask to wear that allowed them to smell what it was that they were supposed to be eating. According to one commentator: “When you get your sample, it comes with something that looks a bit like a medical breathing tube. Fit it around your face, and it holds a small bulb soaked in synthetic chocolate, cod, or peanut butter scent right next to your nose. Once you finish eating [vegetable protein and algae], the attendant pops off the bulb and takes it away, cleaning the frame for the next guest.” Should this dystopian view of the future one day come to pass, then F. T. Marinetti’s conception of plates of food that you would be allowed to smell but not eat from more than a century ago (see the final chapter for more on the Futurists) may turn out to be closer to the truth than any of us realized. In summary, then, there really is no escaping the value that understanding the nose brings to the way we connect to our plates.

In the next chapter, we are going to explore sight. We will take a closer look at the phenomenal rise of gastroporn and the recent emergence of mukbang in the Far East. What’s that? I hear you ask. Well, I’m afraid you will just have to wait to find out . . .