CHAPTER 6

Dahl Surveys Family Madness in Norway, and Darwin Scrutinizes His Own Family through the Lens of Asylum Data, 1859-1875

The “medicine of the future,” in many of its departments likely to become almost wholly preventive, and thus of a public and general character, must owe more and more of its progress to statistical science.

—John Gray (1861)

Such a factor [Anlæg] having once arisen—from unknown causes—in a small and isolated population, may easily increase and disseminate in the course of time, notably by continued marriages in kin already affected.

—Ludvig Dahl (1862)

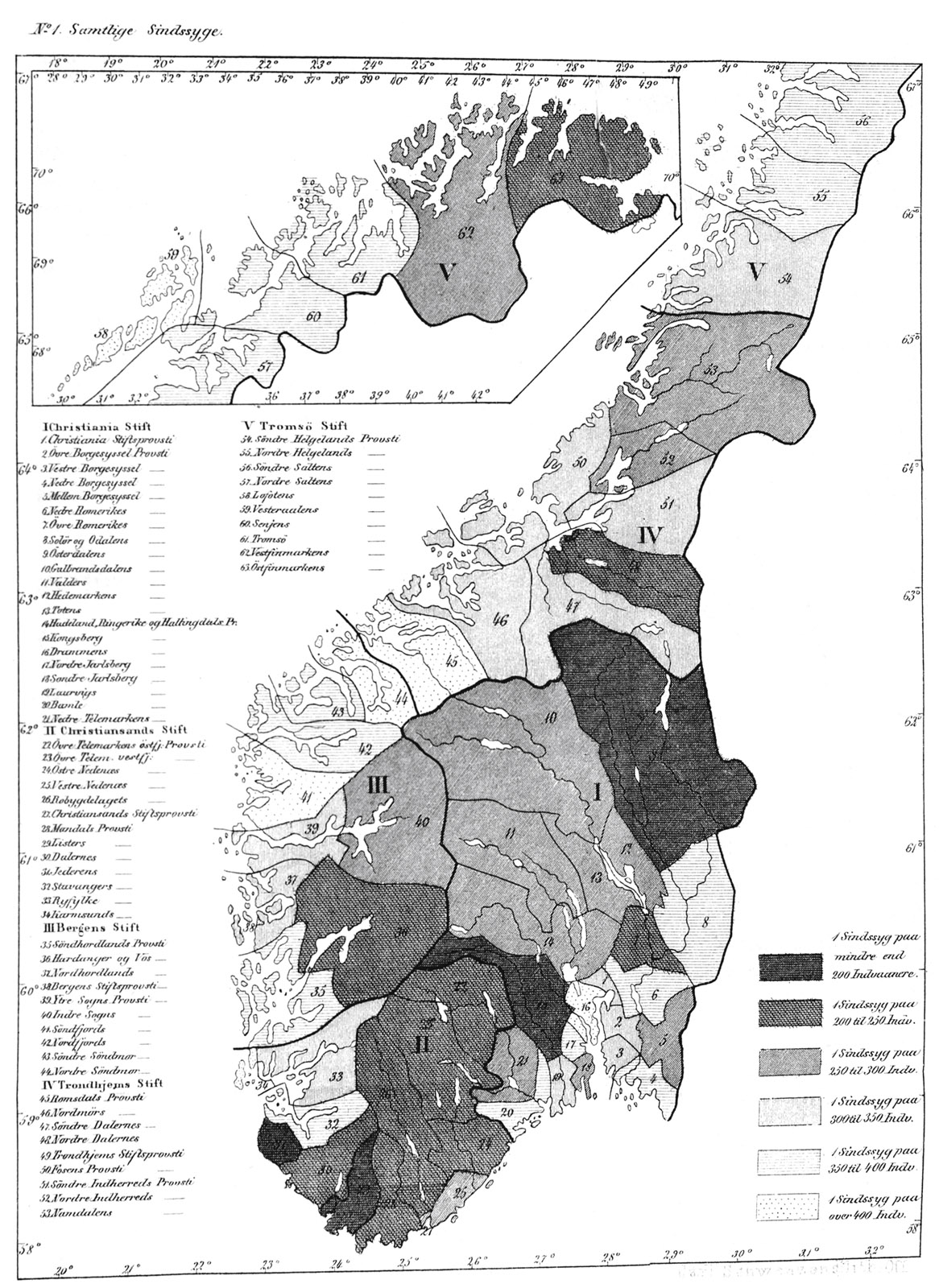

Norway, on the European periphery, had attracted a degree of interest from alienists for its thorough census and—no mere coincidence—its uniquely high measured rates of insanity. In 1857, when Ludvig Dahl quietly began work on his Contribution to the Knowledge of Insanity in Norway, it had only recently set up its first dedicated institutions for the mad. Yet Norway possessed an unusual capacity to survey its population. That infrastructure enabled Dahl to study mental illness outside of asylums at an unprecedented level of detail and to assemble family pedigrees of insanity decades in advance of other countries. He reasoned upward from families to the level of census, putting forward an explanation of geographical differences in the prevalence of insanity in terms of the transmission of hereditary factors. Despite the local specificity of its subject matter and its linguistic inaccessibility, the book attained an international reputation as a key resource for investigating and representing the inheritance of mental illness.

How Much Madness?

In 1860, the American Journal of Insanity printed a list of the proportions insane in different places. The highest ratios were for Norway (1:550), Scotland (1:513), and the canton of Geneva (1:446). John Gray, AJI editor and superintendent of the Utica asylum, lifted these figures from B. A. Morel’s just-published Treatise on Mental Maladies, which followed by three years his initial articulation of the theory of hereditary degeneration in 1857. The new book, focusing more specifically on phenomena of mental illness, reemphasized his commitment to statistics. Morel kept his distance from cultural pessimism, insisting that civilization could no more cause insanity than true religion. Yet he recognized that asylum patients had increased alarmingly, along with the systems that housed them, and he, like so many of his professional colleagues, wondered anxiously where it would end. New counts almost always showed bigger numbers, as in Scotland, for which Morel and his reviewer mentioned a more recent and still higher figure recently published by an Italian doctor, 1:417.1 He had somehow missed an enumeration by a Scottish commission in 1855, distinct from the decennial census, incorporating data from sheriffs, boards of supervisors for the relief of the poor, ministers, and rural constables as well as its own detailed investigations. The figure they eventually released in 1857 implied a ratio in Scotland of 1:390.2

Yet even this was not the limit, as Gray already knew. A still higher ratio appeared six pages up in the same issue of the AJI in a reprinted extract from the Irish medical press, “Notice of Dr. Dahl’s Report Respecting the Insane in Norway.” Since 1825, the Norwegians had counted the insane as part of their decennial census. Morel knew only of the first, probably from Esquirol’s French review. Each successive count revealed some growth of population and a disproportionate increase of insanity. Holst’s figure (1:550), so startling in 1828, had been surpassed in 1835 and again in 1845. The most recent census, made known outside Scandinavia by reviews and discussions of Dahl’s report, found 5,071 insane, including idiots, in a population of 1,490,047. This meant 1 insane per 293.8 of population, a number, as Dahl admitted, without parallel among nations. He warned against exaggerating its significance, and especially against any Norwegian exceptionalism.3 He might as well have commanded the incoming tide to freeze in place. Alienists wanted to know what conditions in Norway could account for this unparalleled scourge.

Gray introduced the next year’s volume with a historical meditation on statistics. “Looking over the annual reports of American Asylums, we need not say how almost entirely they are filled by numerical tables. . . . With a certain license—as pardonable perhaps in the specialist as in the poet, who coerces to the demands of measure or rhyme the noblest and most comprehensive words—these are called ‘statistics of insanity.’ ”4 Gray spoke of license because he knew that statistics, according to its etymology, should be about the state. He explained, incorrectly, that the numerical method in medicine, made famous by Pierre Louis’s test of the efficacy of bleeding, was the model for Esquirol’s (earlier) tables of insanity. Gray declared that statistics had failed utterly in pathology and provided only negative proofs in therapeutics. Now it lingered on mainly in epidemiology and public hygiene, areas of medicine devoted not to individualized treatment but to principles and to masses, where he thought it appropriate.

On this matter he invoked another French source, the 1857 census of establishments for the insane, which the AJI had recently reviewed. He endorsed the claim of the French census director that the greatest predisposing cause of insanity was heredity, yet he attributed the explosive growth of the numbers (from 10,539 in 1835 to 24,524 in 1854) to the magnetic appeal of an expanded asylum system.5 There was no real increase of the insane, he wrote, but only of institutionalized patients. Although Gray’s opening remarks on the tyranny of tables sound cynical, by page 6 he was praising the unified French census for its “thorough system of records” providing indispensable guidance to the legislator. Even as he acknowledged the force of Isaac Ray’s critique of statistics and the obstacles to tallying a thing as fuzzy as insanity, he called not for strategic retreat but for a still bolder advance. Statistics so far had merely recorded the results of insanity, but Morel’s clarified taxonomy opened the door to statistical scrutiny of its pathological development. According to the new French category of “hereditary insanity,” inheritance was no longer a mere symptom but the disease itself. Morel had cleared the way for the “medicine of the future,” which would focus on prevention rather than treatment.6 The case is similar with Norway.

Tracking the Elusive Hereditary Anlæg

Dahl brought research on insane heredity down to the level of minute studies of particular communities. Norway, which in those years was subject to the Swedish king, enacted legislation in 1848 authorizing construction of dedicated insane asylums. The first of these opened at Gaustad, outside Christiania (Oslo), in 1855. Dahl returned from two years of medical study in France, Austria, and Germany to take up an appointment there as assistant physician. He then received a stipend from the Crown of 250 Norwegian Speciedaler to undertake a tour of institutions for the insane in Holland, Belgium, and Great Britain. Adding Denmark to his itinerary, he set off in March 1856, visiting thirty-three asylums in about three months. His report, published in the Norwegian journal of medical sciences, met the usual expectations of the genre, including a basic sketch of the history and laws of each institution, its architecture and layout, sanitary arrangements, medical treatments, daily schedules, and rules of behavior.7

Other nations seemed eager to learn from Norway, whose new asylum attracted laudatory press coverage right from the start. I find no evidence that Dahl visited James Murray’s Royal Asylum at Perth during his visit to Scotland. But when Lauder Lindsay, its superintendent, chanced to travel to Norway on holiday in 1857, he could not resist the temptations of a visit to Gaustad. He wrote a glowing report for the Journal of Psychological Medicine, which was then picked up and debated in Paris at a meeting of the Société médico-psychologique. That discussion formed the basis for a report in the AMP. The building, all agreed, was wonderful. It is perhaps even excessive, wrote Lindsay, who contrasted the intelligence and charity of the Norwegians to the small-mindedness apparent in the designs of so many county asylums in Britain. Brierre de Boismont, in the French report, spoke of a picturesque site and a “veritable palace” whose construction cost six times more per patient than what his colleague Parchappe had described as acceptable for these hospitals. Lindsay derived the same multiplier, six, by comparing its building costs per patient to those for the Scottish asylum in Montrose. Gaustad had rooms enough to do things right: a ward for quiet patients of good social class, another for quiet pauper patients, a third for the noisy and turbulent, a fourth for the excited and destructive, and a fifth for patients who were dirty.8 It went almost without saying that men were kept separate from women.

Brierre de Boismont took great interest in a therapy employed by Ole Sandberg, medical superintendent at Gaustad: a prolonged warm bath combined with cold trickles spilling onto the head. The treatment, he explained, was his own, introduced a decade earlier. A footnote leads us to a paper he read to the Academy of Medicine, with seventy-two patient histories (“observations”) and tables of results according to diverse variables. His remedy had spread to Britain, notably Scotland, after he demonstrated it to David Skae of the Royal Edinburgh Asylum during Skae’s visit to Paris. What a triumph to learn from Lindsay’s review that his baths were in use now in Gaustad as well as Edinburgh and were yielding excellent results! Dahl’s report indicates that he spoke with Skae in Edinburgh, and it is possible that he learned of the head-chilling Brierre bath in this way.9 It is a dense web of alienist connections we confront in these documents.

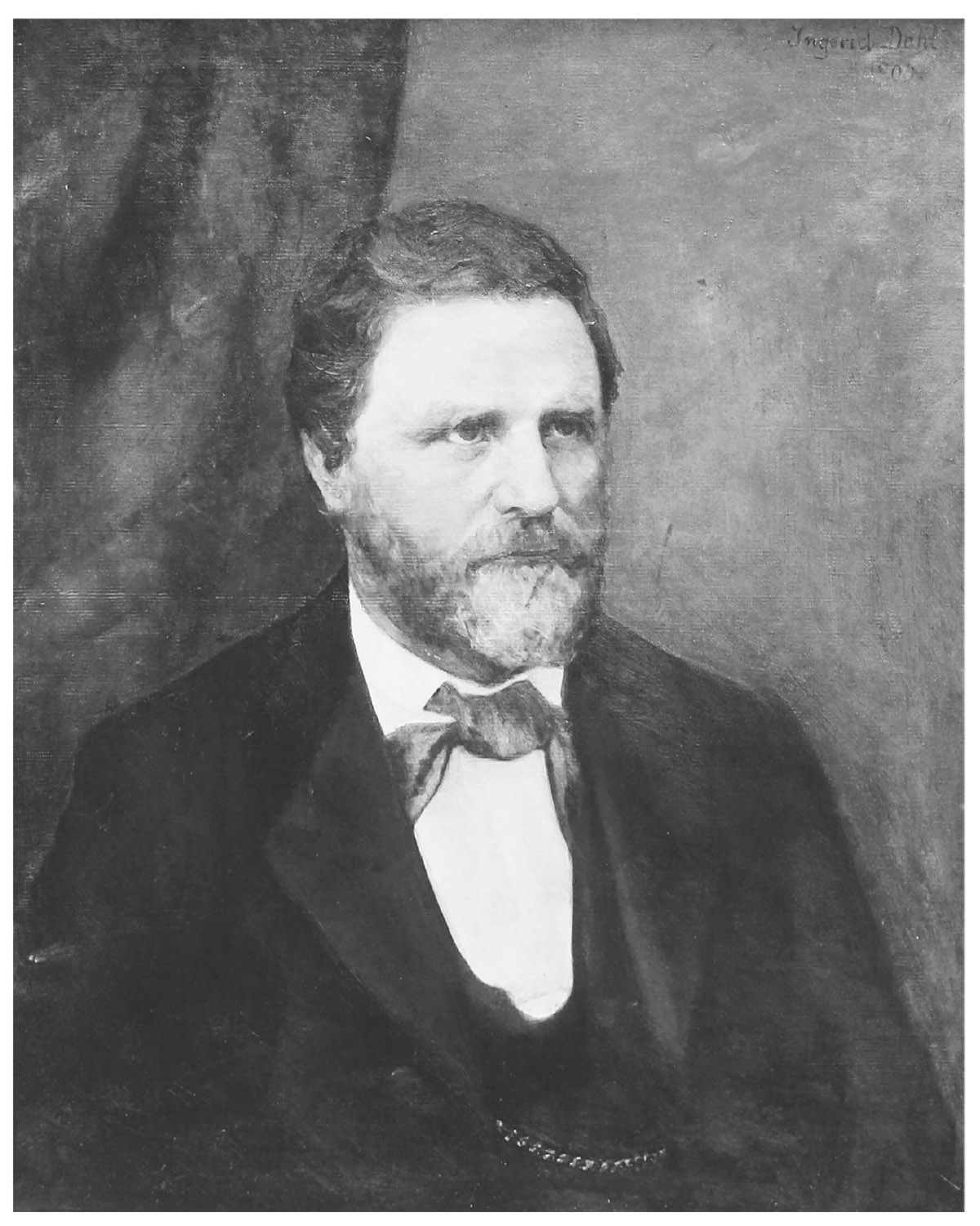

FIGURE 6.1. Ludvig Dahl (1826–1890) combined demographic and historical research with family investigation of the insane in selected parishes of Norway. Image from a painted portrait held by the Norwegian Medical Society, with special thanks to Øivind Larsen. See Øivind Larsen and Magna Nylenna, “Profiler og portretter i norsk medisin,” Michael Quarterly, supplement 11 (2012), 43.

The Norwegians adopted the English model of annual reports, and Lindsay was almost as enthusiastic about the cornucopia of statistical tables on Gaustad as he was about its lavish facilities. His review of the asylum drew also on discussions in French and German medical literature. The table of causes, according to its heading, was based on information from doctors and other relevant sources. In the first report, for 1856–1857, hereditary predisposition (arveligt Anlæg) was the leading cause,10 just ahead of masturbation and drink, both overwhelmingly male, and grief, worry, and disappointments in love, all characteristically female. In subsequent years the order varied, partly due to changes in the terms used and partly to recombinations of categories. But the initial report, which received the most international attention, supported the expectation, originating with Holst’s 1828 census, of the exceptional role of hereditary insanity in a nation of matchless statistics. It went on to list specific family relationships among the patients at Gaustad: father-daughter, uncle-nephew, brother-sister, and the like.11

The most detailed and influential response to Dahl’s book was in Germany. By 1859, much Norwegian scientific and medical research was conducted within the German orbit. The capacity of Scandinavian countries to census or to survey their own populations inspired admiration and a touch of envy from German alienists.12 Although the book was not translated, a long essay in the AZP by Gerhard von dem Busch may have been even more effective. The reviewer, a Bremen physician and translator, was convinced of the profound importance of Dahl’s empirical study for the understanding of causes, especially hereditary ones, and he provided a full translation of the sections concerned with heredity. He also was impressed by the role of the Norwegian state, which was beginning to be recognized for pioneering statistical studies of its own population. It had supported Dahl’s research with funds for seven months of travel and with indispensable infrastructure in the form of census data. Dahl relied on comparative results at the parish level, made visible with shaded maps that he included at the end of his volume, to identify sites of study. He also used census lists to pick out families for closer investigation, tracking down 270 out of the 283 mentally ill recorded by schoolteachers in Trondheim, Bergen, Christiania, and Christiansund. Following a common practice that Holst had made explicit, he took care to distinguish “acquired” (erhvervet) insanity, meaning insanity that arose during or after adolescence, from congenital weakness of intellect, appearing in infancy. Especially for “idiots,” who often died young, he recognized the need to take age distributions into account to sort out misleading frequency differences. His research confirmed Norway’s standing as a test case (we might say model system) for the examination of hereditary insanity.13

Dahl’s hierarchy of causes was in line with Norwegian census results and with tables from the Gaustad asylum. He identified hereditary predisposition and marriages among close relatives as the leading cause of insanity. Merely having mentally ill relatives, he warned, even if these were direct ancestors and even if they suffered the same form of illness, did not prove the existence of a hereditary Anlæg. Proof of heredity had to be statistical. It depended on showing that a disease or disease class appeared much more commonly within a particular family than outside of it and on the absence of any other known causes that could explain it. Possible alternative explanations for childhood idiocy in one or more children included excessive use of brandy by the father and scaring or mistreating the mother.14

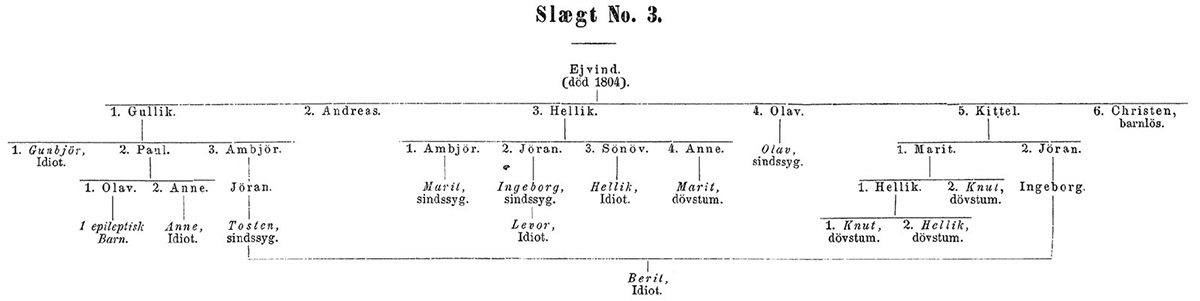

He aimed to uncover families whose bad heredity was beyond doubt. By focusing on regions with relatively stable populations, high rates of mental illness, and frequent marriage within communities, he was able to secure data for pedigree tables of inherited conditions, apparently the first such tables ever printed.15 Much later, about 1900, they became an indispensable template of information for eugenic research, the raw material for investigating the laws of hereditary transmission and for keeping records of good and bad lineages. I am not aware of any others of their kind for two decades after 1859. Dahl’s book included tables of defects he took to be hereditary for eight kin groups, or Slægter. His Slægttavler, kinship tables, became, in von dem Busch’s translation, Geschlechtstafeln, which preserved etymology, or Stammtafeln, both terms used at the time mainly for royal and noble lineages, an ascending line of male ancestors. Dahl’s kinship tables, by contrast, recorded patterns of transmission of an ancestral Anlæg to the descendants. In 1877, when the superintendent of the Scottish National Institution for the Education of Imbecile Children, William Ireland, needed to illustrate the inheritance of mental weakness for a book on idiocy, he reprinted Dahl’s tables with translated captions. Evidently he knew of no suitable English tables of this kind. Ireland called them family trees, here again pouring Dahl’s new wine into a very old bottle.16

FIGURE 6.3. Pedigree chart of mental illness for kin group number 3. These tables attracted international attention and were often reprinted. Dahl’s charts remained of great interest to hereditary researchers on account of the wide range of disabilities he found within kin groups. I have not found pedigree charts of mental illness from other countries until the 1890s. From Dahl, Bidrag.

Dahl’s most certain result, as he called it, and the one that most impressed Ireland, came out of the town of Flesberg, west of Oslo in the parish of Numedal, where he gathered data for his kinship group number 3. The table included 9 insane and idiots, of whom 8 were still living, plus 4 deaf-mutes and one epileptic. In the entire parish he found 24 insane (including idiots) and 6 deaf-mutes. This result was consistent with the 24 insane and 11 deaf-mutes given by the 1855 census, since 5 of the deaf-mutes were also idiots. The census had included them in both categories. In all, he determined, 12 of these 30 insane or deaf-mutes were members of a single extended family, descendants of Ejvind, who had died in 1804. Ireland spoke of “scattered branches of a common ancestor,” every one the victim of “ancestral taint.” A son of Ejvind’s son and a few other relatives assisted Dahl in identifying all living members of this lineage, who numbered 126. Putting this kin group to the side, he observed, would reduce considerably the proportion of idiots and deaf-mutes in the parish of Numedal, population 2,922.17

Dahl was pursuing an alternative to the explanation of rates of mental illness in terms of physical environment, diet, or social milieu, interpreting them instead as an accumulation of diseased family lines. Yet the hereditary Anlæg was an elusive quarry, one that often skipped generations or appeared in collateral relatives rather than in the direct ancestral line. It also varied its form, appearing now as insanity or idiocy, now as epi.tify, now as deaf-mutism or albinism. Sometimes it seemed to be present but not fully formed, as in the case of two sane sisters of dark and violent character who each bore mentally ill children. Although a family Anlæg had real consequences, it was by no means a sufficient cause. A strong Anlæg in the parent, he explained, could increase the frequency of hereditary illness in the children by a factor of 15. The arithmetic seems to refer specifically to Ejvind’s descendants, with 12 insane out of 126 (1:10.5), by comparison to 18 out of 2,796 (1:155) among the remaining inhabitants.18

A year after the publication of his book, Dahl was commissioned to resume the research, first in an area around Trondheim and then in the far northern regions of Nordland and Finnmark. He published these results in the Norwegian journal of medical science as two continuation chapters of his book, which von dem Busch again summarized at length in German in the AZP. The state, having taken responsibility for the health of its population, was pressing forward to gauge the medical needs of the insane in these remote northern regions. Although there were no asylums so far north, Dahl again could rely on the census, now six or seven years out of date, to pick locations for study. Tracking down what information he could, he ended up with a smaller proportion of hereditary cases than in his prior studies. He attributed this difference to incomplete information. Once again, his most startling conclusions involved patterns of inheritance in specific families. None of his far-northern kin groups were so extensive as Ejvind’s, but he printed tables for five of them, each beginning with a male progenitor—an identified or unknown father. These tables omitted the healthy, recording only those lines involving conditions that he thought hereditary, including lameness and epi.tify as well as blindness, deafness, idiocy, and insanity. Some of the children had badly deformed skulls, which he duly measured, and multiple bodily, sensory, or mental problems. Several were products of cousin marriages.19

Dahl chose one small region in Nordland for a model study, the basis for his most striking results of all. This was the parish of Saltdal, running north from the Arctic Circle, which he picked for special investigation on the basis of disproportionately high figures for insanity in the 1855 census. The census there had recorded 11 mentally ill in a population of 1,690, a ratio of about 1:150. When he arrived, the priest told him of 35 insane in the parish. Investigating the matter himself, Dahl found 24 mentally ill and five idiots plus six doubtful cases. He could round this to 30, he proposed, and use 1:60 for the proportion, or he could exclude recent outbreaks involving intermittent illness and call it 15 plus five idiots, a ratio of 1:90. Dahl’s willingness to work with so much uncertainty in his numbers was unusual. Either way, this was undoubtedly a very high number by comparison to census figures for Nordland as a whole, whose ratio was about 1:400. It would be interesting, he thought, to compare Saltdal with the next parish west, Bejeren (or Beiarn), where mental illness was much lower despite similarities of climate and landscape and a diet that, if anything, favored Saltdal. As before, he chose to track the Anlæg rather than to pursue explanations based on geography, diet, or differences of civilization.

In pursuit of his quarry, Dahl inquired locally about relatives of the mentally ill and pored over parish records. A book on the natural and human history of Saltdal, under the title Physisk-oeconomisk Beskrivelse over Saltdalen (Physical-Economic Description of Saltdal), opened up new resources for tracking the insane Anlæg. It was written by Søren Christian Sommerfelt between 1824 and 1827, just after he resigned as parish priest there. He is now best known as a Linnaean botanist who compiled long lists of local plant species. He also inventoried animals, described the geography and climate of the region as well as the character of its inhabitants, and tried to reconstruct patterns of settlement going back to medieval times. Since he had left Saltdal in 1824, he could not very well have been directly involved in Holst’s census of insanity of 1825–1828. But he had already noticed that mental debility in the parish appeared disproportionate to its population, and he proceeded to tally and describe the insane. At least eight current residents, Sommerfelt found, had for some period of time been so violent that they had had to be bound. He added, consolingly, that seven had recovered, leaving only one who, for many years, has been “like a wild beast.” Even her condition was not hopeless, he suggested, for Sommerfelt had found in the church register a still less promising case of a woman who was absolutely crazy for a very long time, and then, when she was almost seventy, suddenly recovered her senses.20

Sommerfelt wrote nothing about heredity, but Dahl relied heavily on his discussion of population movements in the parish. There were, according to Sommerfelt, 1,049 residents at the end of 1823. Examining church registers all the way back to 1730, he counted 2,453 births and 1,777 deaths, implying, he calculated, a population of just 373 at the beginning of the period. He acknowledged that the completeness of the record might be challenged, but in view of the impressive growth of population since his own arrival in 1818 and the much healthier habits of former times, he supposed that the increase since 1730 could easily have been still greater, and, accordingly, the population in 1730 even smaller. Extrapolating backward, he conceived that inhabitants of this valley must have been virtually wiped out by the Black Death in the fourteenth century. On the basis of linguistic patterns as well as the evidence of its oldest surviving houses, he surmised the origins of the new settlers. They must have come in very slowly, beginning with Finns, Lapps, and Swedes from across the Swedish border.21

Dahl accepted this idea of a near extinction and resettlement, including the surprisingly low population number in 1730, and he quoted approvingly Sommerfelt’s remarks on the prevalence of insanity in 1823. He also learned, apparently from the priest in Ranen, the adjacent parish to the south, that a “couple hundred” settlers from Ranen had recently settled in Saltdal and that they were largely free of mental illness. The Anlæg for insanity, Dahl inferred, “seems instead to belong to a tribe originating somewhere other than the neighboring villages.” In Saltdal, as in Flesberg, insanity appeared to be mainly a “family sickness.” He proceeded to scour church records for the identity of Sommerfelt’s “caged girl” (perhaps the one who behaved “like a wild beast”). He learned that she had three brothers, one of whom was “completely insane” and another who was mentally weak to a high degree. Each of these sick brothers, in turn, had fathered two insane children. Dahl prepared no family tables for Saltdal, but he gave a full list of infected families: two families with three mad children each, one family with four, and two more families in which madness affected the mother and two children. He provided no balance sheet, but there seem to have been, in total, from these families alone, 23 mentally ill and one doubtful.22

That would be a solid majority of the 29 confirmed mentally ill in Saltdal. Could the story be simplified still further? Dahl hinted at hopes to comprehend all or most of the mental illness in Saltdal as resulting from the migration of one single Anlæg, perhaps in a few interlinked families. Regrettably, since many of the insane siblings were very old, he was impeded by a lack of reliable information. He read through the church records from 1828 to 1845 without turning up a single marriage of close relatives. There had been a few such marriages more recently, and he reasoned that in a parish so sparsely populated, there must be many marriages between more-distant relatives. “In this way, a sickness-Anlæg that is already present may be strengthened.” He did not overlook other causes. As in his book, and in so many asylum reports from many lands, he put great emphasis on alcohol and masturbation. Other dangers included religious enthusiasm (Svarmerie), spooky folk tales, and dangerously copious bleeding by rough doctors in the far north. Yet he treated all these as secondary, and their bearing on the problem as indeterminate. His crucial finding was “that such an Anlæg, having once arisen—from unknown causes—in a small and isolated population, may easily increase and disseminate in the course of time, notably by continued marriages in kinship groups already affected.”23

It was, in its time, a brilliant research program. Dahl’s hereditary Anlæg seems very like a gene. The appeal of explanations like these has endured into the present era. In the 1990s, for example, geneticists in Arizona proposed to investigate whether (rumors of) an extremely high incidence of schizophrenia among the Havasupai might owe to descent from a single shaman who had lived more than a century earlier.24

Reshaping Heredity

Dahl moved back and forth from the level of large regions, where the methods of the census were appropriate, to towns and parishes, where he could look into houses, talk with the priest, and examine documents pertaining to individuals. In some respects, his investigations were fitted to the template of the asylum report, and he devoted most of his professional life to asylum medicine. Like so many alienists, he understood the main causes he invoked as acting principally outside the asylum and as highly pertinent to public health. This was especially true for heredity, whose dynamics he tracked with unmatched precision. His book “found its way into the libraries of many European neurologists,” wrote Ireland in an obituary notice. “It deals mainly with the causes and distribution of insanity, and especially attracted attention by the careful way in which he traced the descent of hereditary insanity in families dwelling in the quiet valleys of Norway.”25 Dahl focused on marriages among those with a hereditary Anlæg, itself a vital object of study, for the perpetuation of mental and nervous illnesses. This was a theme of growing importance, much discussed by 1859.

For example, in 1857, as we have seen, Lauder Lindsay journeyed to Norway and on a lark, or so he implied, visited Dahl’s asylum at Gaustad. Lindsay’s comments in the annual report of James Murray’s Royal Asylum for 1858 took a very strong line on the role of heredity in the perpetuation of insanity. The official figures for causes, he there declared, are, as usual, valueless, owing to the “imperfect and unsatisfactory data on which they are founded; it were profitless, therefore, minutely to analyse them.” Just why he allowed the records to be kept in so slovenly a fashion is not clear, unless of course his role was simply to record what the families told him. “Excitement in connection with celebration of Burns’ centenary,” an entry from 1859, shows little promise as a generalizable statistical category. There was a clear gap there between causes as recorded and what the alienists believed. His predecessor, William Malcolm, had mentioned hereditary predisposition in 1849 as the principal cause of insanity, even though his table of causes listed not a single man and only one woman under that heading.

Lindsay’s confidence in the causal power of heredity, similarly, did not depend on statistical information from his own institution. His 1858 report is almost shrill in its call for restrictions on the reproduction of insanity. It is difficult to interfere with civil liberty, he said, but perhaps there should be legal restrictions on marriages of the insane. “The propagation of insanity by means of fatuous and facile female paupers is now amenable to civil law.” This language we recognize from the 1857 report of the Royal Lunacy Commission for Scotland, and it may have been reinforced by his discussions at Gaustad. Lindsay’s relationship to statistics changed completely in 1859. Although he complained in the report issued in June 1860 of his dependence on unreliable entries from the schedule of admission, it seems that he was now seizing the initiative. The new report provided full hereditary statistics including, when he had it, specific information on which relatives were affected.26

1859 and All That

To historians of biology, 1859 is Darwin’s year. Francis Galton lauded his cousin’s bold theory for demonstrating the analogies between biological species change and purposeful breeding. Almost everyone since has understood eugenics as what Galton made of Darwin’s legacy. But we have already seen how much more water flowed into this river than can be attributed to the theory of evolution. Darwin, it turns out, was moved by family concerns to take a personal interest in inherited disease. He quickly found his way to medical writings on insane heredity.

By 1859, alienists everywhere recognized heredity as a key cause of the insanity that had filled to overflowing a crowd of new asylums. “Now, in relation to this malady, two important facts have been clearly established,” wrote the Scottish Commissioners in Lunacy in 1859, and proceeded to a discussion of the key role of hereditary predisposition.27 In 1858, a year before Darwin’s Origin, John Gray was provoked by Buckle’s History of Civilization to reassert its importance. “The large amount of statistical evidence in its favor, which Mr. Buckle sees fit to depreciate, is good at least until the first adverse generalizations are brought forward. In the entire medical profession there is almost no dispute of the law of heredity in bodily and mental disease.”28

On 9 September 1859, the festivities organized by the University of Freiburg to celebrate the thirty-third birthday of the grand duke of Baden were capped by a lecture on the inheritance of ethical Anlagen. Alban Stolz, prorector and professor of pastoral theology and pedagogy, explained how free will had been overvalued through inattention to heredity. Many spiritual gifts and much “derangement of spirit and mental illness” are passed on by inheritance from parents to children. A thought experiment will convince us that the effect cannot be reduced to home environment. Imagine removing many children to a house of education where pupils are all treated identically, as if in a factory. They would assuredly yet diverge, each showing characteristics of its parents. Probably he knew nothing of Dahl’s new book, but he called for research like Dahl’s: “more exact observation” of heredity, “carried out statistically,” and collections of exact and well-confirmed cases, such as criminal histories. What was needed was a new specialty in exact science “to serve as a norm of comparison, namely the inheritance of psychical diseases.”29

In 1863, Isaac Ray joined in denouncing the historian’s dismissal of hereditary causation of mental qualities. Buckle’s extreme standard of causal efficacy, if applied more generally and not only to heredity, would block progress in every department of medicine. “The causes of insanity which spring up around us, are of far less potency than those which we bring into the world with us.” Ray’s insistence on hereditary stability of type was so emphatic that it would be impossible to regard him as following Darwin’s lead. He was already writing in a eugenic way five years before the Origin of Species and without a thought of biological evolution. As a specialist in medical jurisprudence and asylum medicine, he could not ignore the hereditary predisposition for criminality and insanity. “None but they who have a professional acquaintance with the subject can conceive of the amount of wretchedness in the world produced by this single cause.” The physician’s wisdom had specific practical bearing for those who thought of marrying, and he warned them against “disregarding a law which carries with it such fearful penalties.”30 At least half the cases in institutions owe to a hereditary tendency. Breeders of animals know enough to insist on a lineage free of hereditary blemish, he wrote in 1853, so why do human families “go on forming alliances for life as if it were a fanciful speculation instead of a very serious fact?” Although there were other deadly causes, notably masturbation, which he saw as the chief causal link between insanity and civilization, heredity seemed a more promising focus of intervention. It was “at the same time the most prolific and the most easily avoided.”31

Ray’s reports from Rhode Island inspired the Lower Canada Lunatic Asylum in Quebec, in 1858, to endorse the analogy between breeding practices of domestic animals and humans. It had already enacted a requirement to report on hereditary taint in every new patient’s application. Of the first 36, 12 certified “that insanity had manifested itself in the parents or in the immediate blood relations.”32

By 1859, eugenics, in a broad sense, was old hat. Health officials may already have put their hereditarian doctrines into practice, as a consideration in decisions to intern insane or imbecile paupers. Dahl’s great admirer, Ireland, remarked in 1877 that “unhappily there are too many instances” on record where imbecile or idiotic women have had children.” He then quoted a reference to the transmission of idiocy for five consecutive generations from an 1857 report of the Royal Commissioners on Lunatic Asylums in Scotland. They announced “alarming figures” from the latest returns, showing no fewer than 126 idiotic women were shown to “have borne illegitimate children and whose mental defect is frequently manifested in their offspring.” The commissioners considered that a full investigation would greatly increase this number and followed with specific instances from certain parishes.

It thus becomes a matter of very serious import, whether for the sake of public morality and civic policy, all fatuous females should not be restricted in their liberty, and be gathered together in poorhouses. If it were possible to place all those who were at a child-bearing age, in circumstances where illicit intercourse would be impossible, much would be done to arrest an evil which has already entailed great misery and heavy burdens upon the community.33

Asylum Data, the Darwin Family, and Family Defect

Darwin first confronted human heredity as a personal issue in 1839, the year of Alexander Walker’s Intermarriage: Or the Mode in Which, and the Causes Why, Beauty, Health, and Intellect, Result from Certain Unions, and Deformity, Disease, and Insanity, from Others. It was also the year he married his first cousin, Emma Wedgwood, and this big, diffuse book, treating domestic animals as well as human ones, made him anxious about the hereditary health of his children. By the year of Dahl’s book, the question whether parents of new patients were blood relations was printed on many asylum admission forms. In consequence, the asylums became indispensable sources of (inconclusive) data on this vital issue. Darwin was greatly interested in 1865 by Galton’s first paper on hereditary talent, but another paper that year on human heredity made an equal impression.

That one, on consanguinity, was written by the deputy commissioner of lunacy for Scotland, Arthur Mitchell. There he described pedigrees that pointed to ghastly hereditary damage. For example: “A married B, his full cousin, and had five children by her.” Child 1 was sound in mind and body; 2 was imbecile; 3 died, age at death and mental condition not known; 4 was imbecile; 5 became insane. In the next generation, child 1 had by first wife four children: 1 was sane; 2 was sound in mind and body; 3 became insane in adult life; 4 died in early infancy; by second wife, five children, and so on. “If it be possible to conceive a family history more melancholy than that presented in the foregoing diagram, we shall find it in the cases which follow.” But a conclusive answer, he acknowledged, required statistics, not just cases. Even collecting every episode that happened to present itself could prove nothing, since they would not be representative. Mitchell proposed two strategies for ascertaining the truth on marriage of relatives. His first was to identify all cases of some defect commonly attributed to consanguinity and see what percentage involved cousin marriage. Although his position as a Lunacy Commissioner gave him privileged access to data on families with mental defect, there were no authoritative figures for the frequency of cousin marriages at large. His second idea was to perform complete counts in several towns to see if idiocy was more common among the children of cousin marriages in these towns. Again his position provided advantages. He chose some locations to visit then “placed a schedule of queries in the hands of willing and competent persons.” The research proved more difficult than he had anticipated, and the results were contradictory. He concluded on a balance of the evidence that cousin marriage does harm the offspring, though perhaps not the children of prosperous and well-nourished families that reside in healthful surroundings.34

While Mitchell referred also to the experience of cattle breeders, Darwin’s attention was most engaged by the human question. He began exploring ways to procure the numbers that Mitchell had called for. By 1868, he was corresponding about the problem with William Farr, who told him in May that the International Statistical Congress, meeting in Florence the previous summer, had passed a resolution in favor of adding a column to census schedules to indicate the relatedness of father and mother of any family. On 17 July 1870, just as Parliament was about to take up legislation authorizing the 1871 census, Darwin asked his friend John Lubbock, an anthropologist and member of Parliament, to propose a new question on cousin marriages. He also wrote that day to Farr, arguing that such data would furnish “a standard by which to judge whether the proportion, (already tabulated in some cases) of persons in asylums for the dumb & deaf the blind & insane who are the offspring of cousins is in excess of the proportion of cousin offspring in the whole population.” Lubbock organized what support he could and put the question to Parliament at 1:30 in the morning on 23 July. It was in vain.35

Darwin then passed the project to his son George, a mathematician. George Darwin made a selection of marriage announcements in the Pall Mall Gazette and of marriages registered at Somerset House and collected genealogies from Burke’s Peerage. He also studied the works of noted alienists and surveyed asylum statistics in consultation with men like Lindsay, Henry Maudsley, Crichton Browne, and George Shuttleworth of the Royal Albert Asylum for feebleminded children. His father wrote to Shuttleworth in 1874 asking him to help George by querying his patients. On the basis of all this data, George reached the Scottish verdict of not proven, but when he read his paper to the (London) Statistical Society, Galton stood up to say that he was too cautious. His paper had swept away an “exaggerated opinion” of the weakness produced by cousin marriage, and Galton knew of populations with much intermarriage that were magnificent. He had great hopes for schemes of inbreeding to generate castes with specific talents. George Darwin and his father, in contrast, were drawn to eugenics more by fear than by hope. These investigations left George deeply disturbed by the inexorable increase of insanity, and in 1873 he wrote a paper for the Contemporary Review advocating restrictions on the liberty to marry.36

Asylum doctors did what they could to turn back the increase of insanity, embracing the public-health role of alienist medicine and stressing prevention over cures. For doctors and patients, the “medicine of the future” might include homeopathy and clean living, but the focus of scientific attention was first of all on the inheritance of mental disease and the reproductive choices or restrictions that could stall or even reverse its inexorable growth.