FOOD

Challenge

A series of coordinated terrorist attacks on the country's food transportation system have left grocery stores unable to restock their supplies. Shelves are quickly emptied, and it may take up to three weeks for shipments to be resumed. How will you feed your family?

When preparing for a disaster, food is often the first need that comes to mind. A good illustration of this is when people rush to purchase milk and bread at the first warning of a bad storm. Admittedly, some people also turn their attention to batteries, generators, and bottled water, but those needs are usually considered after their stop at the grocery store.

Your access to food can be cut off in two different ways. The first is local in nature when stores are forced to close due to an immediate crisis—most often inclement weather. The second situation is one in which the food supply itself is disrupted. What is the likelihood of that? Not as remote as you might think. Minor disruptions occur all the time, often caused by weather events or contamination. For example, recently there was a winter freeze that ruined much of California's citrus crop, and an outbreak of E. coli poisoning that forced the recall of the nation's spinach. More significant disruptions can be caused by many incidents, including a prolonged power outage, transportation problems, major weather events, or an attack on the food supply system.

Did you know that most supermarkets only stock about a week's supply of food? This “just in time” supply system serves everyone well under normal circumstances. The supermarket owner doesn't suffer the overhead of having to hold large stockpiles of goods. And the consumer is guaranteed fresh goods that haven't sat on a shelf for extended times.

Our country has very few small farmers left to provide an emergency food source.

Ask yourself what would happen if the grocery stores were forced to shut down, or if the food supply was disrupted and stores could no longer be resup-plied in a timely manner. Where would your family get food? There are very few small farmers left in the country, so local farmers’ markets wouldn't be much help. Likely it would fall to the government to provide emergency rations, and let's face it; our government hasn't always shown itself to be efficient or timely when it comes to disaster relief.

A self-replenishing food source is the only way to truly be prepared for a long-term disruption.

The only way to be truly prepared for a long-term disruption of the food supply system is to have a self- replenishing food source, such as a farm or livestock. Unfortunately, this is not a practical option for most people. Landlords just wouldn't understand cows in the apartment! Many experts suggest doing the next best thing—stockpiling large quantities of non-perishable food. This book challenges that premise. Instead, the recommendation here is for a modest food storage plan that will meet your family's needs in all but the very worst disaster scenarios.

There are four fundamental questions to consider when preparing a well thought out food storage plan. As it turns out, the answer to the first question determines the answers to the other three.

Fundamental Food Questions

1. How much food should you store?

2. What types of food?

3. How should you store it?

4. How long will the stored food last?

The question of how much food to store ties directly back to the more fundamental question posed in the Introduction. What you are preparing for? The answer ultimately determines the quantity of supplies of every type that you will need. Short-term food interruptions, such as a snowstorm that prevent you from getting to the store, are unlikely to require more than a week's supply. Whereas a terrorist attack on the food supply system might cause shortages lasting weeks or even months—albeit likely limited only to certain food types.

Making preparations requires you to draw the line somewhere. Some preppers gravitate towards extreme, “end of the world” food storage plans but fail to consider the likelihood of such events or the costs associated with that kind of preparation. The recommendations in this book strive to be more practical and pocketbook friendly.

When it comes to food storage, a reasonable approach is to keep a thirty-day supply. Perhaps you are shaking your head in disbelief. You're recalling the advice of numerous experts who suggest having an entire year's supply of food stockpiled. That level of food storage is impractical, wasteful, and almost always unnecessary.

A thirty-day food supply is adequate for all but the most catastrophic of events.

Let's start with impractical. Consider that the average American consumes about 2,000 pounds of food per year. Now imagine a family of four storing four tons of food in a location that is both temperature and humidity controlled. Not only storing it, but rotating it, and keeping it from spoiling or being ruined by pests. A challenge indeed!

Storing such a large quantity of food would likely be very wasteful as well. You would need to master techniques to keep food from becoming contaminated—most likely using nitrogen-purged air-tight containers. Even when you did become skilled at food storage, you would still experience loss due to spoilage, rodents, and insects. This means that you would be required to regularly inspect a huge stockpile of food, discarding and replacing things that were no longer consumable. This would be a costly and time consuming process.

Finally, ask yourself which disasters would require you to have such a large food cache. Go back and examine the Shopping List of Disasters in the Introduction. Of all the disasters listed there, only a few truly catastrophic scenarios would require you to have more than a month's food supply (e.g., asteroid strike, world-wide drought, global war—a truly world changing event). The bottom line is that the sacrifices incurred from storing large quantities of food would very likely be unnecessary.

Consider the impact of every family in America following this recommendation to keep a full month's supply of food. No one would ever have to race to the store when weather threatens. Catastrophic disasters would still cause worry, but the thirty-day supply would give families time: time for the nation's emergency management services to provide relief, time for people to rally with friends and family to pool resources, and time to evacuate to areas where shortages were not as severe.

As with every aspect of preparedness, however, your food storage plan is just that—yours! If you decide that a month's supply isn't enough to protect your family, then by all means store more. But be forewarned, having a large food cache can be expensive and wasteful.

The next step in creating a food plan is deciding what to store. Table 2-1 is an example of what a few entries in a food storage list might look like. A blank food storage worksheet is given in the Appendix. Make a copy of the worksheet, and then fill it in with the food items your family enjoys eating. You may find it helpful to use different color highlighters to color code the foods, indicating if the item is stored in the pantry, refrigerator, or freezer.

Keep the food storage list and a pencil near your pantry, perhaps taped to the door. As you consume items, change the “Qty Needed” to reflect what needs to be restocked. When you take your next trip to the supermarket, bring the worksheet with you as a shopping list. Don't forget to replace the old list with a new blank one.

Feel free to vary it up each week by making food substitutions, such as replacing canned peaches with raisins, but try to stay true to your general dietary goals—discussed in detail later in this chapter.

Far too often, food storage plans consist mostly of bland, easy-to-store food. This is usually a result of trying to store massive quantities of food where shelf life and getting enough calories in the diet are the driving requirements. Unfortunately, little thought is put into how unhappy the menu will make the person having to eat it.

Shying away from very large food plans frees you up to store a wide variety of commercially available food. This type of food plan can revolve around three requirements: (1) nutrition, (2) taste, and (3) shelf life. Your family will thank you for adopting a consumer view in your preparations. No more dehydrated banana chips or molasses-flavored cookies.

Stock up on food that your family enjoys and is accustomed to eating.

To stock up, go no further than your local grocery store or discount warehouse. Storing foods with a very long shelf life, such as military Meals Ready-to-Eat (MREs) are thankfully no longer necessary. If you have ever eaten MREs (or their predecessor, C-Rations), you likely understand. A meal or two can be fun, but eating them as your three squares a day gets old very quickly. I say this as an ex-Army grunt who has eaten his fair share of both.

Gardening, sprouting, canning, and dehydrating are all very interesting, but not necessary for establishing a modest food cache.

There is a line of thinking in the DP community that preparing is synonymous with getting “back to basics.” Many books have lengthy discussions on gardening, sprouting, canning, and dehydrating. Any activity that has you eating healthier is certainly to be encouraged, but understand that these activities aren't necessary to pull together a reasonable food storage plan. Therefore, they are not discussed at length here. If you are interested in learning about these food topics, you should have no trouble finding numerous books specializing in them.

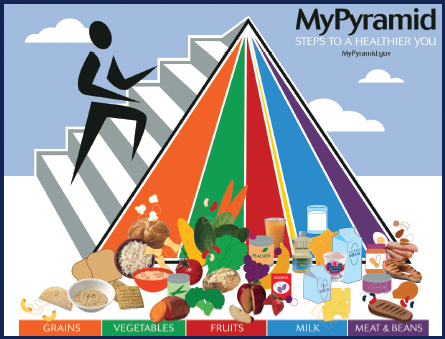

When deciding what types of food to store, sound advice can be found by consulting the New USDA food pyramid.8 The food pyramid was recently updated, and though you may still find it flawed, it provides well-researched guidance to proper nutrition. Contrary to popular belief, creating a stockpile does not mean that you have to store food oddities—don't go out and buy a huge tub of beef jerky thinking that it would make great “survival food.” Stick to what your family eats and enjoys now.

Said another way… store what you eat, and eat what you store. This makes rotation a snap; you put the newest food to the rear, and eat that which is oldest.

When selecting canned goods, opt for those with pull tops. This eliminates the need for can openers, and does not affect the shelf life.

Canned and boxed foods will be perfectly fresh thirty days after purchase. Breads and raw meats must be frozen to maintain a thirty-day supply. Canned meats are also readily available (e.g., Spam, tuna, chicken). As far as dairy, many items have adequate refrigerator life, such as cheese, yogurt, and butter. Shelf stable milk and hard cheeses are options that don't require refrigeration. Shelf stable milk is created using ultra high temperature pasteurization, and has a shelf life of several months. It is offered through several manufacturers, including Borden, Nestlé, and Parmalat, and is readily available at grocery and warehouse stores. For even longer storage, you can keep powdered products, even if just as a backup.

Shelf stable milk (courtesy of Borden)

Be careful not to stock up too heavily on frozen or refrigerated foods because this leaves your food supply susceptible to the loss of electricity. There are, however, a few tricks to keeping food cool during a power outage (i.e., up to a few days).

• Put blocks of dry ice in the refrigerator and freezer.

• Keep the refrigerator and freezer stocked full with little empty space, even if it is just filled with containers of frozen water.

• Minimize the times you open the refrigerator or freezer.

If you do find yourself with extra food that will go to waste due to thawing, invite the neighbors over for a big cookout. Goodwill toward others, especially in times of crisis, can go a long way toward making lifelong friendships. Even if you don't like your neighbors and are not driven by “the common good,” your generosity may well lead to a prudent exchange of resources.

Use food storage as a chance to improve your family's eating habits.

You already know what your family likes to eat, but it wouldn't hurt to review the food pyramid to ensure that you pull together a balanced, nutritious food storage plan. Much of what follows might seem better suited to a guide on nutrition, but an important part of being prepared is stocking your cupboards, refrigerator, and freezer with the right kinds of food.

New food pyramid (illustration by MyPyramid.gov)

In 2005, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) released a significant update to the food pyramid. It is divided into five basic food groups as well as oils/fats. There are also two other categories not explicitly shown by pyramid slices:8

• Physical Activity—illustrated by the person climbing the stairs

• Discretionary Calories—represented by the uncolored tip at the top of the pyramid

Recognizing that everyone is different, the USDA has created an online tool that allows you to create your own personalized food plan. Recommendations are based upon age, sex, size, and activity level. There are also many other useful features, including menu planners, meal tracking worksheets, nutrition tips, food ratings, and more. Go to www.mypyramid.gov to try the interactive tool.

Sample dietary plan (illustration by MyPyramid.gov)

This sample plan recommends consuming 10 ounces of grains, 4 cups of vegetables, 2½ cups of fruits, 3 cups of milk/dairy, and 7 ounces of low-fat meat each day. The specific quantities will vary based on weight, age, and activity level, but the general profile will remain very much the same. Use the new food pyramid's dietary plan to help establish a nutrituous food inventory.

The foundation of the food pyramid is built on grain products, such as breads, cereal, pasta, tortillas, popcorn, oatmeal, and rice. When possible, choose foods made with whole grains over those with refined or enriched grains. The food pyramid recommends that at least half of your grains be whole grains.

Whole-grain foods are made with the entire grain kernel (i.e., bran, germ, and endosperm) and as a result offer more fiber and vitamins, and have been shown to reduce the occurrence of several diseases.9,10,11 Refined grains are processed such that the bran and germ are removed. This is done to give the grain a finer texture and extend the shelf life. The drawback is that removing them also removes much of the fiber and B vitamins. Whole-grain foods are thus healthier, and since they are higher in fiber, they also keep your digestion on track while helping you to feel full longer.

It is also possible to store raw wheat for grinding, but this requires a grain mill (either electric or manual). For very large food stockpiles, a grain mill becomes necessary because raw wheat lasts longer than ground wheat. For the thirty-day plan however, it is not required.

Don't forget to store baking items (e.g., baking powder, baking soda, salt, yeast, sugar, corn starch) if planning to bake your own foods. Home-baked goods are considered healthier because they contain less preservatives. Also include spices and flavorings, such as vanilla, cinnamon, cocoa, and chili powder. As always, the bottom line is to store what you know how to use.

Courtesy of Country Living Productions

You have heard it a thousand times: Americans don't eat enough fruits and vegetables. People use a host of excuses ranging from not liking the taste, to restaurants not offering enough choices. Excuses aside, everyone knows that fresh produce contributes to better health, and is thus deserving of a more concerted effort. Americans in general would be better served by moving away from meats and sweets and toward fruits and vegetables.

You can get your recommended servings of fruits and vegetables many different ways—fresh, cooked, frozen, canned, dried, or even as juice (not the sugar-loaded stuff). Nutritionists recommend eating a variety of fruits and vegetables with different colors and textures. The reason for this is that each food has unique properties that contribute to good health. Try using this excursion into disaster preparedness to take two actions:

1) Try new foods—Try those fruits and vegetables that you have passed by so many times in the grocery store fearing that you wouldn't like the taste. You may stumble upon a gem while contributing to your own good health. Besides, having a broad appreciation of a variety of foods is a valuable DP skill since it will help you adapt to dietary changes introduced by food shortages.

2) Eat a more balanced diet—Consume more fruits and vegetables, and try some of the whole-grain products available today. Eating more fruits and vegetables will likely help you lose any unwanted pounds, thereby improving your health and helping you to be more physically active. Physical ability is often important when facing the challenges associated with a disaster, such as repairing your roof, hiking down to the river for water, or clearing the roadway of fallen trees.

Fruits and veggies (USDA photo)

It is no surprise that the food pyramid recommends consuming pri marily low-fat dairy products. They are significantly lower in calories and saturated fat than the full-up versions. A diet low in saturated fat is believed to help maintain low cholesterol, which is an important part of heart health.12

Dairy products can include such things as milk, cheese, yogurt, pudding, and ice cream. For those who are lactose- intolerant, there are many lactose-free dairy products now available.

Lactose-free dairy (USDA photo)

Protein sources include a wide variety of meat, poultry, fish, beans, eggs, nuts, and seeds. The food pyramid recommends that you opt for lean meats, fish, and poultry with the skin removed. Try to avoid processed meats since they often contain added sodium and other ingredients that can best be described as “miscellaneous animal parts.”

Proteins (NCI photo)

Protein can also be found in a wide variety of beans and peas. Eggs are another good source of protein, but be aware that the yolks are high in cholesterol (containing about 70 percent of your recommended daily allowance). A healthier choice is to eat only the whites if you are going to eat eggs often.13

As far as nuts and seeds, the medical community has recently recognized that eating 1 ½ ounces of nuts per day may reduce the risk of coronary heart disease.14 Keep in mind that nuts are high in calories, and an ounce is only a small handful (about ¼ cup).

Most people have no trouble getting enough fat in their diet. From butter, to mayonnaise, to cooking oil, to animal fat, to candy bars, fat is everywhere! You can't escape it.

Oils are simply fats that are liquid at room temperature. Most are high in monounsaturated or polyunsaturated fats, low in saturated fats, and have no cholesterol. Notable exceptions are coconut and palm kernel oil, which are high in saturated fats—very undesirable. Cooking oils include canola oil, corn oil, cottonseed oil, olive oil, safflower oil, soybean oil, and sunflower oil.

Fats and oils (NCI photo)

Solid fats are just that—fats that are solid at room temperature. This includes food items such as butter, margarine, vegetable shortening, beef fat (tallow, suet), and pork fat (lard). Solid fats come from many animal products and can also be made from vegetable oils through a process called hydrogenation. The American Heart Association (AHA) recommends that you consume fats and oils with less than 2 grams of saturated fat per tablespoon, such as canola, olive, and soybean oils.15

The AHA also recommends limiting dietary fat to 30 percent of total calories. How easy is this to do? Consider that whole milk gets about 48 percent of its calories from fat, peanut butter—75 percent—and steak—52 percent.16 It's quite easy to see why people routinely exceed the 30 percent calories-from-fat recommendation. Short of having to live on lean, wild rabbits, it is difficult to imagine a case where inadequate fat intake would become a health concern.

Even under the worst of times, it is hard to imagine not getting enough fat in our diets.

Sweets and sweeteners fit best into this category too. Sweeteners include such things as sugar, brown sugar, honey, maple syrup, corn syrup, and artificial sweeteners. Consider stocking a collection of sweeteners for fresh-baked goods, as well as a small supply of your family's favorite sweets (e.g., candy bars, brownie mix). They can help make life a bit more pleasurable, which can offset some of the hardship.

The message here is that now is a good time to introduce your family to a balanced, nutritious diet. The new food pyramid can help you craft a healthy eating plan. As far as food storage, increase your stockpile of foods to a minimum of thirty-days supply, being careful not to rely too heavily on frozen or refrigerated foods. Also, remember to store what you eat and eat what you store—no need for “survival food.” This strategy keeps waste to a minimum. Perhaps this food storage plan lacks the adventuresome feel of storing a bunker full of military rations. It is, however, practical and would serve your family well in hard times.

One final thought on food storage—of all the steps in the DP process, stockpiling food will provide you with the most unique sense of security. Every time your family asks, “What's for dinner?” and you have dozens of choices at your fingertips, you can't help but feel better prepared. Try it, and you will quickly discover the comfort in having well-stocked cupboards.

Having a food stockpile gives a unique sense of security.

Food storage shelves (courtesy of Shelfreliance.com)

The difficulty of storing food is directly proportional to how much you decide to store. Larger storage plans present significant challenges, including storage space, rotation, infestation, and spoilage. If you are on board with the thirty-day food plan, then the biggest challenge is simply finding enough space.

To help you better appreciate just how much food is required for thirty days, go to your cupboards and count up how many full meals you have (breakfast, lunch, and dinner). If you are like most families, your current stockpile is somewhere around five to seven days, with lots of little extras that don't necessarily fit into a specific meal. Take a moment to imagine what thirty days of food might look like. Would it even fit in your cupboards? Probably not. More than likely you will have to be a bit creative and free up some closet space or perhaps keep extra food in out of the way places. Many people find that the wasted space under a stairway can be easily converted to a convenient food pantry.

Canned and boxed foods are best stored in dry conditions where temperatures are kept fairly constant, ideally between 40°–60°F.17 Keep food away from appliances or heating vents where undue heat could cause spoilage. Storage places could include a basement, under your stairs, closets, a utility room, kitchen cupboards, or even under your bed. Due to wide temperature swings, storing extra food in the garage or attic is probably a bad idea. Try to keep all but canned foods off the ground to minimize potential problems with bugs, rodents, or moisture. If you are tight on space, check out www.shelfreliance.com, a provider of slanted shelves that allow efficient storage of canned foods, and make rotation a snap.

If you have opted for a larger food storage plan, then you will need to do your homework and learn important storage methods; most of which depend on storing bulk food in airtight containers. Plastic buckets and mylar-foil bags are effective at keeping out air, bugs, and light—all of which can compromise your food cache. Don't store food in garbage bags because the bags may contain pesticides and are made of plastic resins that are not recommended for contact with food.18 A good deal of advice regarding large food plans can be found in Spigarelli's Crisis Preparedness Handbook.19

Refrigerator thermometer (courtesy of Taylor)

When storing refrigerated foods, the temperature should be kept between 34°–40°F.20 Cool temperatures help slow the growth of bacteria, extending the shelf life of foods. To ensure that you have the proper refrigerator temperature, check it in several places using a small refrigerator thermometer. Make sure that the highest reading is no more than 40°F. Here's your first big investment—a $10 thermometer!

Optimal Temperatures

Pantry: 40°–60°F

Refrigerator: 34°–40°F

Freezer: 0°–5°F

Frozen foods should ideally be kept at 0°F but never above 5°F.20 Once again, you can use the refrigerator thermometer to ensure you have the proper setting. As a rule of thumb, if your freezer can't keep a block of ice cream brick solid, then it is set too high. It is a good idea to put a freeze date on your freezer foods if they aren't already dated by the store. Also, freeze foods in moisture-vapor-proof pack-ages, such as zippered freezer bags, or airtight freezer containers. Poorly sealed freezer packaging can lead to freezer burn.

You might think that if you limit your food supply to thirty days, then spoilage won't be of much concern. While it is true that a smaller storage plan does remove much of this worry, there are still several reasons why every prepper should be aware of the shelf life of different foods:

1. During a crisis, food poisoning can be potentially life threatening. Knowledge of food safety is therefore critical.

2. Even with a modest thirty-day food plan, spoilage can still affect some of your supplies (e.g., thawed meats, fresh produce, dairy).

3. In situations where you are forced to scavenge for food, you will need to assess whether that food is safe to eat.

4. If you ever decide to adopt a larger food storage plan, shelf life is critical to planning your stockpile and establishing a rotation schedule.

The first thing to know about shelf life is that it is affected by many factors and is therefore impossible to precisely predict. Food can degrade and become dangerous to consume due to either microbial or non- microbial causes. Some forms of microbial growth are easily seen, such as the fuzzy mold that grows on food that sits in your refrigerator for too long. Other types of bacteria are more difficult to detect. Eating contaminated food is dangerous because it can cause a variety of different foodborne illnesses, a discussion of which is given in the next section. The time it takes for microorganisms to affect foods depends on the particular methods used in production as well as storage conditions.

Non-microbial spoilage includes moisture gain or loss, chemical effects leading to changes in color or flavor, light-induced rancidity or vitamin loss, and physical damage (e.g., bruising of fruits/vegetables, denting of cans).21 Beyond spoilage, food can also be ruined by rodents or insects.

Foods can develop an unpleasant odor, flavor, texture, or appearance due to bac terial spoilage. Don't initially taste test food to see if it's spoiled. Rather, begin by checking it for bulging, bubbles or foam, mold, or cloudiness. If it looks okay, check to see if it smells sour, cheesy, fermented, or putrid. Next, touch the food to see if it has become slimy. Finally, if it passes the visual, smell, and touch tests, taste a small quantity to see if it tastes okay. If the food has become sour, bitter, chalky, or mushy, spit it out immediately.19

When in doubt, throw it out!

If any of the above char acteristics are noted, the food should be immediately discarded. Your senses are trying to warn you! Food can also be mishandled, causing bacteria to grow rapidly. A well known example is that leaving hot dogs sitting in the sun for several hours at a picnic will cause them to spoil prematurely.

Food that is properly handled and stored at 0°F will remain safe almost indefinitely. Only the quality of food (e.g., tenderness, flavor, aroma, juiciness, and color) suffers from lengthy freezer storage.23 This rule applies to freezer burn as well. Freezer burn occurs when air reaches the food's surface and dries the product, usually due to the food not being wrapped in air-tight packaging. Freezer-burned food is safe to eat. Simply cut away the affected areas before or after cooking.

Food kept frozen at 0°F can remain safe almost indefinitely.

For additional information on food safety, check out the Department of Health and Human Services website at www.foodsafety.gov. It contains useful information regarding food safety, food poisoning, and current recalls.

If you should ever become ill, and suspect it is due to food contamination, save the packaging materials. Label any remaining food as “Dangerous,” and freeze it for future examination by health officials. If the food is a meat or poultry product, call the USDA Meat and Poultry Hotline at 1-888-674-6854. If it is something other than meat or poultry, or is from a restaurant, contact your local health department. To locate the phone number for your local health department, consult the Health Guide USA website.24

In times of crisis, you definitely don't want illness added to your list of troubles. Traveling to a doctor may prove difficult or even impossible, and medical facilities are likely to be overwhelmed. Having to rough it out during a disaster can be bad enough, but doing so while hovering over the toilet can make it nearly intolerable. The following sections provide brief descriptions of seven important foodborne illnesses found in the United States (and throughout the world). The purpose of reviewing them is to become familiar with their symptoms and likely causes. This information is drawn from several references.25,26,27,28,29,30 Later, some simple but effective ways to prevent food poisoning are discussed.

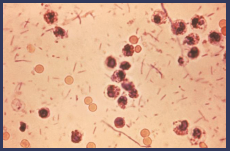

How you get it: Salmonella is a rod-shaped motile bacterium that occurs widely in animals, especially poultry and swine. Salmonella is frequently contracted by eating food contaminated with animal or human feces (a.k.a., fecal-oral contamination). Contamination often occurs when the food preparer doesn't wash his hands after using the toilet. Other possible sources include undercooked eggs, poultry, or meat; and unpasteurized milk or juice.

Salmonella (NIAID photo)

What it causes: Onset of salmonellosis typically occurs within one to three days. Acute symptoms can last a few days to a week and may include nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramps, diarrhea, fever, and headache. Additionally, arthritic symptoms may follow three to four weeks after the onset of acute symptoms. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) estimates that 2–4 million cases of salmonellosis occur annually in the United States.

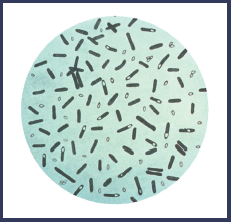

How you get it: Campylobacter jejuni is a slender, rod-shaped bacterium that causes campylobacteriosis. Most cases result from eating raw or undercooked poultry, or from cross-contamination. The bacteria are often found in healthy cattle and birds. Surveys show that 20–100 percent of retail chickens are contaminated. However, properly cooking chicken will kill the bacteria. C. jejuni is also contracted from contaminated water and unpasteurized milk.

What it causes: Onset of symptoms usually occurs two to five days after ingestion of the contaminated food or water. Symptoms can include diarrhea, fever, abdominal pain, nausea, headache, and muscle pain. The illness generally lasts seven to ten days, but relapses are also common. C. jejuni may also spread to the bloodstream and cause a life-threatening infection. Surveys have shown that C. jejuni is the leading cause of bacterial diarrheal illness in the United States. The FDA estimates that there are at least 2–4 million cases annually.

C. jejuni (USDA photo)

How you get it: Clostridium perfringens is a sporeforming, rod-shaped bacterium that is widely distributed in the environment, and can be found in decaying vegetation, marine sediment, and the intestines of humans and domestic animals. Consumption can cause C. perfringens food poisoning. Eating of improperly prepared meat or meat dishes (e.g., gravy, stew) is the main source of infection. Food may be either undercooked or prepared too far in advance of consumption. This bacterium is often referred to as the “cafeteria germ” because most outbreaks occur at institutional kitchens in hospitals, school cafeterias, prisons, and nursing homes.

Clostridium perfringens (CDC photo)

What it causes: Symptoms usually start eight to twenty-two hours after consumption and include abdominal cramps and diarrhea. The illness is usually over within twenty-four hours, but less severe symptoms may persist for one to two weeks. Symptoms may last longer in the elderly. C. perfringens is the third most common foodborne illness in the United States with an estimated 250,000 people affected annually.

How you get it: Escherichia coli are a large and diverse group of bacteria. Some strains are harmless, while others can cause diarrhea, urinary tract infection, or respiratory illness. The most commonly identified Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC) is E. coli O157. When you hear reports about outbreaks of E. coli, they are usually referring to this particular strain. Infections are caused by fecal-oral contamination (i.e., ingesting small quantities of human or animal feces). This can be caused by consuming contaminated food or water, drinking unpasteurized milk, or coming into direct contact with human or animal feces. Other possible sources include under-cooked hamburger, and unpasteurized milk or juice.

Escherichia coli (USDA photo)

What it causes: Symptoms of STEC infections include severe stomach cramps, diarrhea (sometimes bloody), vomiting, and a mild fever. Most people recover within a week. Onset of symptoms may begin anywhere from one to ten days after infection. Very young victims may develop hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS), which may cause acute kidney failure. The FDA estimates that 70,000 cases of E. coli O157 occur each year in the United States.

How you get it: Shigella are non-sporeforming, rod-shaped bacteria that cause shigellosis. Shigellosis is primarily a human disease, not found in animals except monkeys and chimpanzees. There are several different types of Shigella bacteria, but Groups B and D account for almost all the cases in the United States. The organism is frequently found in water polluted by human feces. The disease is most often spread through fecal-oral contamination. It is particularly common with toddlers who are not fully toilet-trained. Shigellosis can also be contracted by eating contaminated food. Uncooked salads (e.g., potato, tuna, shrimp, macaroni, and chicken), raw vegetables, milk, and dairy products are all foods that may be contaminated. Water can also become contaminated if sewage runs into it, or if someone infected with shigellosis swims in it.

Shigella (CDC photo)

What it causes: Symptoms usually occur twelve to fifty hours after ingestion and may include abdominal pain, cramps, diarrhea, fever, vomiting, blood/pus/mucus in the stool, and difficulty defecating. Shigellosis typically resolves in five to seven days. A severe infection can occur in children under age two resulting in high fever and seizures. An estimated 300,000 cases of shigellosis occur annually in the United States.

How you get it: Clostridium botulinum is a spore-forming, rod-shaped bacteria that produces a potent neurotoxin. Seven types of botulism are recognized (A–G), of which types A, B, E, and F cause human botulism. Food botulism is a rare but severe type of food poisoning caused by the ingestion of foods containing the potent neurotoxin formed during growth of the organism. The toxin is heat-sensitive and can be effectively destroyed if heated to 176°F for a minimum of ten minutes. Sausages, meat products, canned vegetables, and seafood products are the most frequent vehicles for human botulism. Most of the outbreaks in the United States are associated with inadequately processed home-canned foods, but commercially produced foods have also been involved (e.g., Castleberry's hot dog chili in 2007).

Clostridium botulinum (CDC photo)

What it causes: The botulism toxin causes paralysis by blocking motor nerve terminals. The flaccid paralysis progresses downward, usually starting with the eyes and face, moving to the throat, chest, and extremities. When the diaphragm and chest muscles become paralyzed, respiration is impaired and death from asphyxia can result. The incidence of this type of poisoning is very low, but the mortality rate is high. Annually, there are on average ten to thirty outbreaks of food botulism in the United States.

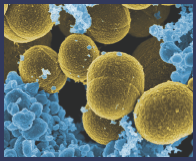

How you get it: Staphylococcus aureus is a spherical bacterium capable of producing a highly heat-stable enterotoxin that causes illness in humans. The most common way of contracting Staphylococcal food poisoning is through contact with food workers who carry the bacteria, or by eating contaminated foods. It is usually associated with meat products, poultry and egg products, homemade salads (e.g., egg, tuna, chicken, potato, macaroni), cream pastries and pies, and dairy products.

What it causes: Onset of symptoms is usually rapid and may include nausea, vomiting, retching, abdominal cramping, and exhaustion. In severe cases, headache, muscle cramping, and changes in blood pressure and pulse rate may occur. Recovery may require a few days. The incidence rate of staphylococcal food poisoning is unknown due to poor reporting of the illness and frequent misdiagnosis.

Staphylococcus aureus (NIAID photo)

The CDC estimates that 325,000 hospitalizations and 5,000 deaths occur every year in the United States due to foodborne illnesses.27 To help combat food poisoning, a partnership between the USDA Food Safety and Inspection Service and the FDA Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition established the Fight BAC! campaign.31 Their recommendations are obvious, yet important. Millions of people get food poisoning each year from not following these simple steps.

Avoiding Food Poisoning

Clean

Clean

Separate

Separate

Cook

Cook

Chill

Chill

1. Clean—Wash hands, kitchen utensils, and surfaces with hot, soapy water. Many foodborne illnesses occur due to fecal-oral contamination. This is often caused by someone with “dirty” hands touching the food, a utensil, or a kitchen surface. After washing, a weak bleach solution (1 tbsp bleach to 1 gallon water) can also be used to sanitize cutting boards or utensils. Always rinse fresh fruits and vegetables with tap water, scrubbing lightly.

2. Separate—To prevent cross-contamination, separate raw meat, poultry, and seafood from ready-to-eat foods. Use separate cutting boards and knives. Never place cooked or ready-to-eat foods on a plate or surface that had raw meat on it previously.

3. Cook—Cook foods to safe internal temperatures. Table 2-2 gives minimum safe internal temperatures for various food types. Use a clean thermometer to test temperatures. Color is not a reliable indicator of doneness. Also, keep cooked foods hot until they are eaten. Bring sauces, soups, and gravies to a boil when reheating.

4. Chill—Refrigerate leftovers and takeout foods within two hours. Refrigerate perishables as quickly as possible after purchase. Keep cold foods cold (34°–40°F for refrigerated, 0°F for frozen). Never defrost food at room temperature. Most food can be thawed in one of three ways: in cold water, in the microwave, or in the refrigerator. Food thawed in the microwave or in cold water should be cooked immediately.

Table 2-2 Minimum Internal Temperatures30,32

Category |

Food |

Temp. (°F) |

Ground Meat & Meat Mixtures |

Beef, Pork, Veal, Lamb |

160 |

Turkey, Chicken |

165 |

|

Fresh Beef, Veal, Lamb |

Steaks, Roasts, Chops |

145 |

Poultry |

Chicken, Turkey, Duck, Goose |

165 |

Pork, Ham |

Fresh Pork |

160 |

Fresh Ham |

160 |

|

Precooked Ham |

140 |

|

Eggs & Egg Dishes |

Eggs |

Firm |

Egg dishes |

160 |

|

Leftovers & Casseroles |

Leftovers |

165 |

Casseroles |

165 |

|

Seafood |

Fish |

145 |

Shrimp, Lobster, Crab |

Flesh opaque |

Having your family follow these four simple steps will significantly reduce their chances of contracting food poisoning. A few additional suggestions that will further reduce the likelihood of contamination are listed below.

• Make sure that poultry is adequately cooked. The meat juice should run clear, not pink.

• Don't eat raw or undercooked eggs or homemade products with raw eggs, such as salad dressings, mayonnaise, ice cream, cookie dough, and frostings.

• Don't consume unpasteurized milk or juices.

• Avoid swallowing water from swimming pools, lakes, ponds, or streams.

• If your tap water has been declared unsafe, cook or peel all fresh produce.

• Follow strict hygienic practices when home canning, especially with low-acid foods, such as green beans and corn. Boil all home-canned foods for ten minutes before eating.

Except for infant formula and some baby food, product dating is generally not required by federal regulations. State food dating requirements vary. If calendar dating is used (a.k.a., “open dating”), it will include both month and day. Also, a phrase must be included to indicate the meaning of the date, such as “use by” or “best before.”

Product dating is misleading because most labels DON'T indicate food safety dates.

Fortunately, manufacturers have voluntarily labeled the vast majority of foods with freshness dates. However, there are several different types of phrases associated with these dates, and this can cause confusion about what is safe to eat. Take a moment to go through your cupboard and locate the dates on various types of food products. They are not always easy to find—sometimes hidden under flaps or stamped into the paper. An understanding of the following food dating terms will help you put meaning to the dates.23,33,34

This is the last date a product is deemed to be at its best. This date recommendation is based solely on flavor or quality. It is not a food safety date, however, highly perishable foods may present a safety risk if consumed after this date.

This date indicates the last day the product can be sold. The “sell by” date tells the retailer how long to display a product. The date is quality driven, and is not a food safety date.

The expiration date indicates the last date a food should be eaten or used. This is a food safety date.

Foods that are not already labeled by the manufacturer should be manually labeled following the guidelines given in shelf life tables (see next section).

Many published tables detail the expected shelf life of pantry foods. The tables presented here are based on input from several sources.20,25,30,35,36,37 Keep in mind that shelf life tables generally represent conservative estimates, and in many cases, food will last longer. For example, there are tales of people eating canned food after twenty or more years of storage. That's not something to be recommended, but you get the point.

When storing pantry food, remember three words: cool, dry, and sealed.

The most important recommendation regarding pantry food is to keep it cool, dry, and tightly sealed. Heat and moisture are bacteria's best friends and will speed up the spoilage process. Air, on the other hand, will dry out exposed food and cause flavor and color changes due to oxidation.38

Another way to extend the shelf life of food from the grocery store is to buy the freshest products available. Check the dates on packages whenever in doubt. Dusty cans or icy deposits may indicate old stock. Don't purchase dented or bulging cans as this may indicate spoilage. Also, don't purchase frozen goods whose boxes are discolored due to having been wet as this might indicate that they were inadvertently thawed during transport or during stocking. Feel free to cherry-pick the foods from the back of the shelf to find those that are freshest.

Table 2-3 Cupboard Storage Chart

Food |

Recommended Storage Time |

Baking powder |

18 months |

Baking soda |

2 years |

Beans/peas, dried |

1 year (airtight container) |

Biscuit, brownie, muffin mixes |

9 months (airtight container) |

Bouillon cubes, granules |

1–2 years |

Bread crumbs (dry) |

6 months |

Bread |

3–5 days |

Cakes - purchased or prepared - mixes |

1–2 days 1 year |

Canned foods, unopened |

2+ years |

Catsup, chili sauce - unopened - opened, sealed well |

1 year 1 month (refrigerate) |

Cereal, ready to eat - unopened - opened, sealed well |

6–12 months 2–3 months |

Cheese, grated Parmesan - unopened - opened, sealed well |

10 months 2 months (refrigerate) |

|

- unsweetened - semi-sweet - syrup, unopened - syrup, opened, sealed well |

18 months 18 months 2 years 6 months (refrigerate) |

Cocoa |

Indefinitely |

Cocoa mixes |

8 months |

Coconut, shredded or canned - unopened - opened, sealed well |

1 year 6 months (refrigerate) |

Coffee - cans or bags, unopened - cans or bags, opened - instant, unopened - instant, opened |

2 years 2 weeks (airtight container) 1–2 years 1–2 months (airtight container) |

Coffee creamers, dry - unopened - opened, sealed well |

9 months 6 months |

Cookies - homemade - packaged |

2–3 weeks (airtight container) 2 months |

Corn syrup |

up to 3 years (refrigerate to extend life) |

Cornmeal |

1 year (airtight container) |

Cornstarch |

18 months (airtight container) |

Crackers |

3 months |

Fish, canned |

3–5 years |

Flour - white - whole wheat |

6–8 months (airtight container) 6–8 months (airtight container) |

|

- canned, unopened - mix, unopened |

3 months 8 months |

Fruit - dried - fresh |

6 months (airtight container) 3–5 days (longer in refrigerator) |

Fruit juice - canned - juice/drink boxes |

9 months 9 months |

Gelatin |

18 months |

Grits |

1 year (airtight container) |

Honey |

1 year—if crystallized, warm opened jar in hot water. |

Hot roll mix |

18 months |

Hot sauce |

2 years |

Jellies/jams |

1 year (refrigerate after opening) |

Marshmallows |

2–3 months (airtight container) |

Mayonnaise - unopened - opened |

4–6 months 2 months (refrigerate) |

Milk - condensed, unopened - evaporated, unopened - nonfat dry - shelf-stable, unopened |

1 year 1 year 6 months (airtight container) 2–3 months |

Molasses - unopened - opened |

2 years 6 months (refrigerate) |

Mustard, prepared yellow - unopened - opened |

2 years 6–8 months (refrigerate) |

|

- in shell, unopened - vacuum can, unopened - vacuum can, opened |

4–6 months 1–3 years 3 months |

Pancake syrup - unopened - opened |

18 months 3–4 months (refrigerate) |

Pasta - spaghetti, macaroni, etc. - egg noodles |

2 years (airtight container) 6 months (airtight container) |

Peanut Butter - unopened - opened |

6–9 months 2–3 months Natural peanut butter must be refrigerated after opening. |

Pie crust mix |

8 months |

Pies and pastries |

2–3 days Refrigerate whipped cream, custard fillings. |

Popcorn, unpopped |

2 years (airtight container) |

Potatoes - instant mix - fresh |

6–12 months (airtight container) 2–4 weeks (keep in dark place) |

Powdered drink mix |

18–24 months |

Pudding mix |

1 year |

Rice - white - brown, wild - flavored or herb |

2 years 6–12 months 6 months |

|

- bottled, unopened - bottled, opened - made from mix |

10–12 months 3 months (refrigerate) 2 weeks (refrigerate) |

Shortenings (solid) |

8 months |

Sauces and gravy mixes |

6–12 months |

Soft drinks |

6 months |

Soup mixes, dry |

1 year |

Soy sauce - unopened - opened, sealed well |

3 years 9 months |

Spices and herbs |

6 months–2 years, depending on type (airtight container) |

Sugar - brown - confectioners - granulated - artificial sweeteners |

4 months (airtight container) 18 months (airtight container) 2 years 2 years |

Syrup - unopened - opened |

18 months 1 year (refrigerate) |

Tea - bags - instant - loose |

18 months (airtight container) 3 years 2 years (airtight container) |

Toaster pastries |

2–3 months (airtight container) |

Vanilla (and other extracts) - unopened - opened, sealed well |

2 years 1 year |

|

- onions - potatoes - sweet potatoes |

2 weeks 2–4 weeks 1–2 weeks |

Vegetable oils - unopened - opened |

6 months 1–3 months |

Vinegar - unopened - opened |

2 years 1 year |

Just as there are storage guidelines for shelved foods, there are also recommendations regarding the usable lifetime of refrigerated and frozen foods. The storage times listed here assume that food has been stored in appropriate airtight containers, and that temperatures are maintained properly (i.e., 34°–40°F for refrigerated and 0°F for frozen). Note that the freezer storage times are provided for optimum quality only, since food can be stored almost indefinitely in a properly cooled freezer.

Table 2-4 Refrigerator and Freezer Storage Chart

With all this talk of storing what you eat and eating what you store, you might think that there is never a need for food with an extended shelf life. On the contrary, long–shelf life foods are useful for stocking food pantries that are infrequently accessed. A good example of this is food that might be stored by your disaster preparedness network to serve those who find themselves underprepared. Another example is a food bank established by a church or civic organization to be used for community emergency relief. Food caches such as these are not likely to be accessed under normal circumstances but could prove lifesaving when a serious disaster occurs.

One of the primary reasons individuals give for creating an infrequently-accessed food cache is to prepare for “the end of the world as we know it” (TEOTWAWKI) scenarios. These scenarios center around a high-impact, low-frequency (HILF) event occurring that completely breaks down modern civilization, leaving every family to fend for itself. Certainly these events are possible, with a short list including a large solar flare, electromagnetic pulse, deadly pandemic, asteroid strike, supervolcano eruption, or nuclear war. Any one of these could certainly set our planet back a century or more. However, by definition, HILF events are highly unlikely. Therefore, it can be argued that TEOTWAWKI preparations should be made only after preparations are in place for more commonplace disasters. Also, it's a good idea for families to periodically eat from their emergency cache, allowing everyone to become familiar with the food before being forced to rely on it.

Distributing emergency food rations (U.S. Navy)

Regular canned food, such as vegetables, soups, or potted meats, can be used for an emergency food bank. However, you may find it difficult to store in bulk due to weight and size. Also, the shelf life of canned products may not be adequate for long-term storage. Over time, food deteriorates in quality and nutrients even when left unopened. Long-term storage is best achieved with highly-stable food products. With that said, canned food may still be edible for many years past its expiration date, albeit with reduced nutritional content. There is no one right answer to how long a food will last because it is a strong function of the particular food type, storage conditions, and canning conditions. Given that canned foods typically have a shelf life of at least a few years, why bother with specialty items such as MREs, dehydrated, or freeze-dried products? The answer is found by better understanding these important emergency foods.

Meals, Ready-to-Eat (U.S. Army)

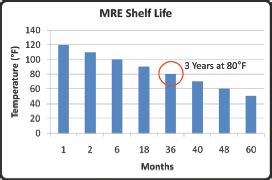

The military first delivered MREs to soldiers back in 1981 to replace the existing C-rations. The MRE I was the first incarnation of a “meal in a bag” that has become the staple field ration not only for the military services, but also for emergency relief activities. Meals, Ready-to-Eat have improved significantly since their first release and now include flameless heaters, freeze-dried coffee, Tabasco sauce, shelf-stable bread, biodegradable spoons, and even high-heat-stable chocolate bars. Every year, the least accepted menu items are discontinued and new recipes are tried out. Not only are MREs convenient and tasty, they also contain about 1,200 calories and meet the Office of the Surgeon General's nutritional requirements. This, along with their stringent durability requirements, including surviving airdrops and extreme temperatures, make MREs a truly remarkable emergency food.

Contents of a modern MRE (U.S. Army)

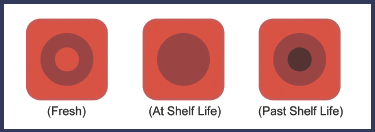

Shelf life of MREs

Contrary to misinformation found on the Internet, MREs have a shelf life of three years (assuming a storage temperature of 80°F). Many retailers claim that MREs have a shelf life of ten or more years, but that is not true for modern MREs unless stored at very low temperatures. Studies have shown that in many cases MREs are safe to eat beyond the three-year expected life. However, every food type deteriorates differently, so it's impossible to make a sweeping statement such as “MREs will last x years before making you sick.” With all food, let your senses be your guide. If the food smells or tastes bad, is discolored, or has changed consistency, toss it out.

Freezing MREs can cause the packaging to delaminate.

Over the past few years, cases of MREs have been equipped with time-temperature indicators (TTIs) to help consumers know if the food has reached the end of its shelf life. The indicators are very effective at reducing waste and ensuring consistent food quality. The TTI starts off with a dark outer reference ring and a bright red inner circle (aka the bulls-eye). The center darkens over time, with the color change occurring more quickly at elevated temperatures. For example, if the MREs are stored at 80°F, the circle will take thirty-six months to darken to match the outer ring. Likewise, if the MREs are stored at a cooler temperature, the circle will take longer to darken. This time-temperature behavior makes the TTI an absolute reference for determining the freshness of the MREs. The lighter the inner circle, the fresher the food. When the inner circle matches the color of the outer ring, the MREs are considered to be at the end of their shelf life. If the inner circle is darker than the outer ring, the MREs are past their shelf life and should be carefully inspected prior to eating. Keep in mind that if you purchase individual MRE pouches or a case of MREs without a TTI, there is no way to determine the remaining shelf life of the food.

Time-temperature indicators

While there is still some question as to the legality of selling MREs to individual consumers, they are readily available. Besides getting them from friends or family members in the military, you can also find them at army surplus stores, guns shows, and on eBay. Beware that many of the MREs for sale are past their expiration date and/or may not be equipped with TTIs. Limit your buying to cases equipped with TTIs that clearly indicate the product's freshness. Many times, sellers on eBay will state the “inspection date” of the MREs. This is simply the projected three-year shelf life date and assumes storage at 80°F. If the food was stored in hotter conditions, the end-of-shelf-life will arrive sooner than this date. Likewise, if it was stored in cooler conditions, the end-of-shelf-life will arrive after the inspection date. For this reason, it is better to use the TTI to determine the freshness of the MREs rather than a projected expiration date. Also, be aware that many vendors sell non-military, prepackaged meals under the guise of being MREs. Some of these products are perfectly fine for long-term storage, but their food, packaging, and contents do not necessarily meet the standards set forth by the military.

Personal aside: I was serving as an Army paratrooper in 1981 when MREs were first introduced. It didn't take long to conclude that carrying heavy-duty pouches of food was a really good idea. For one thing, they could easily be carried in cargo pockets without bruising up your leg every time you dove to the ground. They also came with chewing gum and a clean eating utensil, and they didn't require using the notoriously slow P38 can opener. As for the food in those early MREs, it could best be described as tolerable.

Many people have experience with dehydrated foods, whether it be from snacking on dried fruits or using dehydrated beans and vegetables in recipes. Dehydration is the process of removing most of the water from food, leaving it lighter, smaller, and with a much longer shelf life. The food can be eaten directly or rehydrated by allowing it to sit in hot water for several minutes. Keep in mind that storing dehydrated or freeze-dried foods is of little benefit unless you also have access to sufficient potable water. Don't make the common mistake of focusing heavily on food storage while neglecting to also have an adequate backup water plan.

The texture of dehydrated food is typically chewy because the dehydration process is completed slowly and at warm temperatures. If you wish to make your own dehydrated food, home-based systems are readily available and easy to use. Most dehydrated food is made as a single item, such as mushrooms, apple slices, or beans. The dehydration process does not lend itself well to more complex one-package meals.

THRIVE dehydrated food in one-gallon cans (courtesy of Shelfreliance.com)

By removing most of the water from the food, the shelf life is significantly increased (typically ten to fifteen years when kept unopened in modest temperatures).

Freeze drying is a process in which food is flash frozen, the ice evaporated away, and the food sealed in a vacuum package. This rapid freezing and sealing process requires sophisticated equipment and is not able to be done easily at home. Since nearly all of the water is removed, it is very lightweight, and the shelf life is significantly improved (e.g., five to seven years for pouches, ten to twenty-five years for larger cans). Freeze-dried products are quickly rehydrated by adding hot water.

Since freeze drying is a fast, uniform process, storage of more complex foods is possible. Entire meals are often freeze dried in a single package, such as spaghetti, clam chowder, beef stroganoff, and chicken stew. This meal-in-a-package functionality gives freeze drying the advantage over dehydration when storing for emergency purposes.

Freeze-dried food tends to keep its original appearance better than dehydrated, and that leads many people to say that it looks more appetizing. As a simple example, the figures on the next page show a side-by-side comparison of dehydrated and freeze-dried strawberries.

Alpine Aire seven-day emergency freeze-dried food unit

A more complete comparison of MREs, dehydrated, and freeze-dried products is given in Table 2-5. Each food type has its respective advantages and disadvantages. Meals, Ready-to-Eat are convenient and do not require water but have the shortest shelf life. Dehydrated food is the cheapest option but doesn't offer meal-in-a-package functionality. Freeze-dried food has a very long shelf life and food complexity but requires rehydration. Regardless of what long-term food type you select, be sure to have a clear understanding of its respective place in your overall food storage plan.

Dehydrated and freeze-dried strawberries (courtesy of Faith E. Gorsky of AnEdibleMosaic.com, and Freeze Dried Food Suppliers)

Personal aside: One thing that is often overlooked when selecting emergency rations is just how edible the food is. Any of the options discussed above will certainly keep you alive. But remember, your goal is not only to survive but also to maintain a reasonable quality of life. Your family has to be willing to eat the food that you store! Keeping this in mind, my family conducted a very unscientific comparison of emergency foods by taste testing an assortment of military MREs, freeze-dried dinners from Alpine Aire Foods, and an emergency food bar from Vita-Life Industries. Admittedly, the food bar was not meant to be eaten except during extreme situations (e.g., stranded at sea), but we thought it would be fun to throw in. The food was then ranked according to three metrics: appearance, taste, and consistency. The average of those results are provided in Table 2-6.

The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, brought renewed focus on shoring up the country's defenses. In 2002, Congress and the president together enacted the Public Health Security and Bioterrorism Preparedness and Response Act.39 The law is worth reading and can be found at the FDA website on Food Defense and Terrorism.40

The Bioterrorism Act is divided into five sections:

• National Preparedness for Bioterrorism and Other Public Health Emergencies

• Enhancing Controls on Dangerous Biological Agents and Toxins

• Protecting Safety and Security of Food and Drug Supply

• Drinking Water Security and Safety

• Additional Provisions

There are numerous goals and provisions outlined in the document. How well they will actually protect the population against a terrorist attack on the food, water, or drug supply is anyone's guess.

Food exposed to radioactive fallout requires cleaning prior to eating. Radioactive particulates should be rinsed off canned foods before opening. Boxed foods can also be cleaned off and consumed if the food is sealed inside an airtight bag. Produce should be washed and peeled to remove any radioactive fallout. Foods that can't be thoroughly cleaned, such as opened cans or breads, should be discarded.41

Food exposed to radiation can be safely eaten if handled properly.

When stockpiling food, it is important to consider any special needs that your family may have. This includes baby food, pet food, and food for those with dietary restrictions. See Chapter 15 for more information.

There tends to be two camps of people: those who swear by multivitamin supplements, and those who believe they are a waste of money. The people in favor of daily multivitamins will argue that the diet of the average American is sorely lacking in important nutrients. Those opposing the use of vitamins will cite studies that show that high levels of some vitamins and minerals have been shown to cause health problems as well as interfere with medications.42,43,44,45

Fortunately, almost everyone seems to agree that daily multivitamins should be taken during times of bodily stress, such as when pregnant, confined indoors for an extended period, or eating a restricted diet. Therefore, in situations where food quantity and selection might be limited—such as during a disaster—taking a multi-vitamin supplement seems both reasonable and prudent.

For most people, pets are members of the family. Don't forget to keep the same thirty-day supply of food for your pets. For dogs and cats, this isn't usually difficult—stocking a spare bag of dry food in the cupboard, or rotating canned food. Of course, if you run out of pet food, it may be possible (depending on the type of animal) to improvise by feeding your pets “scraps” from your meals. It might not be the healthiest diet, but it beats starving. Fortunately, most animals quickly adapt to scavenger mode when the need arises.

Don't forget the needs of your four-legged friends.

A much more complete set of recommendations regarding pets is given in Chapter 15.

Take a good inventory of the consumable non-food items in your kitchen, making sure that you have an adequate supply. This list would include such items as aluminum foil, plastic wrap, paper products, plastic utensils, plastic storage bags and containers, and napkins.

There is certainly no need to go out and purchase a new set of kitchen supplies, but you should do a quick inspection of your utensils and pots and pans. During a disaster would be a poor time to realize that your only manual can opener is being held together by zip ties.

Using disposable paper products can help reduce water consumption.

Most families have a shelf lined with cookbooks. It would be wise to select one of your favorites (perhaps an all-purpose cookbook from Betty Crocker, Better Homes, or Mark Bittman) and familiarize yourself with different recipes. If you are stranded at home for an extended period, you may need to improvise by pulling together dishes using only the particular ingredients you have on hand. Learning a few shortcuts and substitutions now means you won't find yourself staring at a cupboard full of supplies during a crisis wondering how best to use them. Also, knowing how to cook using your microwave or barbeque grill can be especially handy for situations with limited electrical power (see “Cooking” in Chapter 7).

Store a minimum of thirty days of non-perishable food.

Store a minimum of thirty days of non-perishable food.

Consult the USDA food pyramid when deciding what to store. See www.mypyramid.gov.

Consult the USDA food pyramid when deciding what to store. See www.mypyramid.gov.

Store what you eat, and eat what you store.

Store what you eat, and eat what you store.

Rotate your food. Newest to the back; oldest to the front.

Rotate your food. Newest to the back; oldest to the front.

Always keep pantry food cool, dry, and tightly sealed.

Always keep pantry food cool, dry, and tightly sealed.

Sweeteners, oils, and seasonings are not critical to survival but can ease the hardship by making food more enjoyable.

Sweeteners, oils, and seasonings are not critical to survival but can ease the hardship by making food more enjoyable.

Consult product labels and shelf-life tables to determine how long foods will store safely.

Consult product labels and shelf-life tables to determine how long foods will store safely.

Don't forget to stock up on non-food and special need items.

Don't forget to stock up on non-food and special need items.

Food poisoning can turn a bad situation into a deadly one. Practice the four steps (clean, separate, cook, and chill) to avoid food poisoning.

Food poisoning can turn a bad situation into a deadly one. Practice the four steps (clean, separate, cook, and chill) to avoid food poisoning.

Recommended Items—food

A stockpile of food

A stockpile of food

a. Minimum of thirty days of food that generally satisfies the guidelines of the USDA New food pyramid and does not rely heavily on refrigeration

b. Any special needs foods, including baby food, pet food, and dietary restricted foods

Refrigerator/freezer thermometer to properly set the temperatures

Refrigerator/freezer thermometer to properly set the temperatures

Non-food items (e.g., aluminum foil, paper products, plastic utensils, plastic storage bags, napkins, cooking utensils)

Non-food items (e.g., aluminum foil, paper products, plastic utensils, plastic storage bags, napkins, cooking utensils)