SHELTER

Challenge

Your microwave oven short-circuits in the middle of the night, igniting a house fire. The fire smolders for several hours before spreading, filling the house with smoke. Do you have the correct smoke alarms to detect the slow-burning fire? How will your family evacuate the house if the primary exit is impassible? Can your children escape without your help? Does everyone know what to do once they get out of the house?

There is a well understood order to wilderness survival: shelter, water, and then food. The idea is simple enough. You must first protect yourself from the environment, whether it is the heat of summer, the frost of winter, or the drenching rains of spring, before worrying about what you are going to eat or drink. This generally holds true for disaster preparedness as well. The only difference is that you are not typically required to build a shelter. Rather, you will need to effectively use and protect the shelters you already have.

In order of importance: shelter, water, then food.

Your home—a generic expression for a house, apartment, townhouse, mobile home, and so forth—is the shelter that your family will most likely depend on when confronting a disaster. Certainly there may be times when you are forced to evacuate, in which case you will have to secure a new shelter. However, for most situations, your family will be much better served by staying put. As shelters go, your home is far superior to anything you can construct ad hoc. If you don't believe this, try spending a cold, rainy night in your yard under the best shelter you can build in half a day. You will quickly come to enjoy the comforts provided by your home, even with the power, water, and gas all turned off.

Your home as a shelter (photo by FEMA/Dave Gatley)

There are certain threats that require specialized shelters. For example, buried or hardened shelters offer the best protection from radioactive fallout.91 They can be built from conventional materials (stone block, concrete, etc.), or they can be made from such things as fuel tanks, shipping containers, steel culverts, Quonsets, or pre-made fiberglass inserts. However, they are not generally the best solution to more common disasters.

Take a look at the list of disasters in the Introduction and you will see that, for most situations, a buried bunker doesn't really offer any advantage over a conventional house. Specialized shelters of this sort are also very expensive for a private individual, not to mention nearly impossible for people living in metropolitan areas. For these reasons, this chapter focuses on issues related to using a conventional residence as an effective shelter. A section in Chapter 13 discusses the special case where you find yourself on the road depending on your automobile to serve as an emergency shelter.

In general, there are three important steps in preparing your home to be an effective shelter:

1. Assess what protection your home provides.

2. Make improvements to increase that level of protection.

3. Safeguard your home to prevent loss, damage, or deterioration.

Begin by evaluating the safety that your home provides. Factors that weigh into this evaluation are construction, geography, and distance from likely threats.

• Construction—What is your house made from? Brick, wood, vinyl, or sheet metal? Are there any specific threats to which your house's construction will be particularly vulnerable? Are there large exposed windows, and if so, can they be shuttered? Do you have a basement that might flood? Is the construction solid? Can you identify any obvious weaknesses, such as an exposed carport with insufficient supports or a roof with loose shingles?

• Geography—In which part of the country do you live? What weather events are most likely to affect you? Are there any specific geological threats such as mudslides, avalanches, earthquakes, rockslides, or sinkholes? Does the landscape offer any natural protections? Are you on the coast where ocean-related weather events, such as hurricanes or nor'easters, pose very real concerns? Is your home situated in a valley that might flood from heavy rains? Are you close to a river or lake that could overflow its banks? Are you off the beaten path, making it difficult for repair crews to get to you?

• Distance from likely threats—Do you live near a nuclear or industrial plant that might release an airborne contaminant? Are you in a metropolitan area (e.g., New York, Los Angeles) that might experience a terrorist attack? Do you live near a railway or airport at which a major crash might occur?

List of Threats

Flood

Flood

Earthquake

Earthquake

Snow storm

Snow storm

Tornado

Tornado

Hurricane/typhoon

Hurricane/typhoon

Winter freeze

Winter freeze

Ice storm

Ice storm

Thunderstorm

Thunderstorm

Lightning

Lightning

Heat wave

Heat wave

Wildfire

Wildfire

Drought

Drought

Volcanic eruption

Volcanic eruption

Landslide

Landslide

Tsunami/tidal wave

Tsunami/tidal wave

Avalanche

Avalanche

Home invasion

Home invasion

Pandemic

Pandemic

Blackout

Blackout

Hazardous material spill

Hazardous material spill

Air pollution

Air pollution

Water pollution

Water pollution

Radioactive material release

Radioactive material release

Chemical release

Chemical release

Food contamination

Food contamination

Fire

Fire

Military attack

Military attack

Biochemical attack

Biochemical attack

Riot

Riot

Hail

Hail

Sinkhole

Sinkhole

Airplane/train crash

Airplane/train crash

Consider the list of threats in the tip box. How likely is each to affect you? How much protection would your home offer? What steps can you take to improve that level of protection?

To make your home threat assessment a little easier, a blank worksheet is included in the Appendix. Table 4-1 serves as an example of what a threat assessment entry might look like. This particular example is assessing a home against f loods.92,93,94

Assessments are completely subjective—you can rate your home at whatever level you think appropriate. The point of the exercise is to have you think about your home's vulnerabilities, and then take steps to reduce them. Realize that many of the threats listed are unlikely, requiring little or no preventive action. Again, the key to practical preparation is to identify the likeliest (or most worrisome) threats first and make improvements to reduce their impact.

Personal aside: Many years ago, I lived in a mobile home in rural Alabama. I scrutinized the weather regularly, fearing the announcer would utter the single word we all dreaded—tornado. When twisters were spotted anywhere in the vicinity, alarms would sound for miles, and my family would race to a small brick building that the landlord provided for just such occasions. The lesson that I took away from the experience was that it is very important to understand what protections each type of shelter offers. In my case, the small reinforced brick building was much more likely to survive the winds of a tornado than a mobile home constructed of sheet metal and particle board. With that said, I never felt the need to evacuate when thunderstorms, ice storms, blackouts, or winter snow threatened. And in general, I think I got it right. My rather fragile house was perfectly capable of handling certain dangers, but ill-equipped for others.

A home is only as good as the elbow grease put into it. It needs to be maintained with diligence. Major systems include roofing, heating and cooling, appliances, plumbing, electrical, and structural. Each system should be regularly inspected, and any problems discovered should be repaired without unnecessary delay—an empty pocketbook being the most likely cause of a “necessary delay.” Think of your house as your personal fortress against the dangers of the world. In doing so, give it the attention that it deserves.

One of the first things you should do is learn how to shut off your utilities (e.g., electricity, water, and gas). Don't just think you know how to shut them off. Go through the motions a couple times. Keep the necessary shutoff tools near the cutoff points. This way you won't have to hunt for them when trouble is knocking on your door. One word of caution: don't actually shut off your gas. It may require a professional to come out to turn it back on. That can be a hassle, not to mention expensive.

Even if you do maintain your home properly, damage will undoubtedly occur. Perhaps high winds or a fallen tree are to blame. In the case of a quickly passing disaster, you can simply head to your local home improvement store, or call your insurance company to hire appropriate contractors to make repairs.

Home Repair Supplies

A good set of hand tools

A good set of hand tools

Basic home repair materials

Basic home repair materials

Home fix-it books

Home fix-it books

Cleanup equipment

Cleanup equipment

If the danger is more prolonged, you may need to make impromptu emergency repairs to patch a leaky roof, cover a broken window, or replace a cracked pipe. For these home repairs, you will need a few tools and supplies. However, it is not necessary to have a toolkit that would make Bob Vila proud. Your money is better spent elsewhere. For now, a basic set of tools that you know how to use (e.g., hammer, screw drivers, wrenches, hand saw, pliers, pry bar) will suffice.

Likewise, limit your construction materials to only those needed to perform emergency repairs on your home (e.g., fasteners, plastic sheeting, PVC fittings, duct tape). You don't need pallets of sheetrock or bags of concrete. Just keep it simple. Pick up a few home fix-it manuals to help you understand the basics of home repair.

It's a good idea to have some cleanup equipment on hand too, such as shovels, an axe, wheelbarrow, heavy broom, and a chain saw if you can afford one. All of these items can be very useful for cleaning up after a major storm blows through.

Cleanup equipment can be useful for clearing roads, digging out, and putting your property back in order.

As for proficiency, that comes with practice and perhaps a bit of one-onone instruction from a local handyman. Developing some basic knowhow will not only help you to make emergency repairs, but also to appreciate the details of your home's construction.

Personal aside: When a particularly nasty nor'easter blew through town a few years ago, I had to carefully hang outside my second story window to secure a large tarp over a leaky window. It was an unpleasant (and very wet) job, but I did feel fortunate to have had the right materials available to keep my house from becoming a swimming pool.

There is one particular area that often doesn't get the attention it deserves, and that is hardening your home from intruders. It is not necessary or even wise to be paranoid, but it is important to be honest enough to accept that bad things can happen to good people. Home invasions and burglaries occur in nearly every community, and during times of crisis, even otherwise law-abiding people may feel compelled to take desperate actions.

Try this simple thirty-day challenge. Imagine for a moment that a nasty-looking thug comes up to you and says, “In thirty days, I am going to break into your home and scare the hell out of you and your family.”

What would you do? Call the police—for sure. Get a gun—probably. One thing for certain is that you would turn your attention to hardening your home and preparing your family. The point in posing this ridiculous scenario is to motivate you to take some precautionary steps that might one day prevent you from becoming a victim of theft, burglary, or home invasion.

It is possible to transform your house into a “hard target” without turning it into a maximum-security prison. Consider some of the many proven methods used to improve your home security and deter criminals.96,97,98,99,100

The first step in being safer at home is becoming more cautious.

Before you even think about hardening your home, teach everyone in your family to be more cautious. Even simple actions like keeping all your doors and windows locked, whether you are at home or away, will go a long way toward keeping your family safe. It is estimated that 90 percent of all illegal entries occur through doors.100

Be careful about how you open your door, and who you open it to. Never blindly open the door—always look first. Ideally have a peephole, chain lock, or floor-mounted retractable door stop to help you better assess the situation. If you see an unexpected repairman, or a suspected evangelist or solicitor, simply don't open the door to them. They will get the message and move on to the next house. If an unknown person persistently knocks on your door, call a neighbor to come over to back you up. Finally, never allow your children to open the door unattended.

Personal aside: When I was in college, one night at around 1:00 AM someone began banging on my apartment door. Purely by coincidence, I was up that night cleaning my handgun from a day at the range. I foolishly answered the door without checking the peephole, thinking that someone was in trouble—perhaps needing medical attention. What I found was a scruffy-looking man who smelled of booze and whose intention never became fully known. When he saw the pistol hanging loosely at my side, he apologized and hastily stumbled away. I was fortunate that my mistake didn't cost me my life.

A guard dog can be a wonderful companion and an almost unbeatable security system.

Take steps to make it harder for someone to surprise you. Consider installing an electronic home security system. Even if the system just serves as a noise-maker, it will alert your family when someone tries to enter your home while you are asleep. The noise may also be sufficient to scare away an intruder.

An alternative is to have a guard dog act as your early warning system. But don't rely wholly on your pet's natural instincts. Take time to teach your dog that security is an important part of his/her role in the family. A point of distinction is in order. A guard dog is a dog that will make noise when someone tries to enter your home. It could be as tiny as a Chihuahua. An attack dog is a dog that will viciously attack an intruder. Unless you live alone and know how to handle a trained attack dog, you should definitely limit yourself to a guard dog. They are much easier to train, and can serve as a loving companion.

(Wikimedia Commons/Ana Kompan)

Courtesy of Heath Zenith

Keep the exterior of your home well lit using floodlights and motion-detector lighting under the eaves or in the yard. Keep bushes and tree limbs cut back to prevent anyone from hiding outside your home, or using trees to access your upper floors. Put gravel or pebbles under the windows as a noise deterrent. Also, consider planting thorny bushes, such as Barberry or Hawthorne, in front of the windows.

Never let anyone other than family or friends know when you or your spouse will be out of town. If the house is empty, use light timers to make it seem like someone is at home. It is also useful to create the illusion of additional security by keeping a large set of boots or a dog bowl with the word “Killer” on the front porch. A home security sign in the yard can act as a similar deterrent.

Shore up your doors and windows. Install heavy-duty, solid-core external doors and deadbolt locks with 1-inch or longer bolt throw. Replace hinge screws with longer wood screws (2 inches for doors, 3 inches for frames). Replace strike plates with high-security models. At a minimum, replace your existing strike plate screws with 3-inch wood screws. If it isn't possible to install adequate locks, consider using inexpensive security bars that wedge between the doorknob and floor (e.g., Master Lock 265), or keyless security latches that are many times stronger than deadbolts (e.g., Meranto DG01-B).

A simple step to improving a door's security is to install longer screws in the hinges and strike plate.

If you have a glass window in your door, it may be possible to install shatterproof plastic or security glass—assuming it doesn't already have it. If that's not possible, you can line the glass with security film, such as 3M's Prestige.

Don't use double-cylinder locks in your home because they introduce a fire safety hazard.

For French or double doors, use inset-keyed slide bolts at the top and bottom to lock in place the lesser-used door. For sliding glass doors, you can drill a hole in the door and frame and insert a locking steel pin, use a window bar, or insert a rod (wood or metal) in the bottom track to prevent it from being forced open.

A lock is only secure if the intruder doesn't already have the key. Don't hide a key outside—especially not under the mat, above the door frame, or in nearby flower pot. It is much better to give a spare key to a neighbor or relative. If you move into a new home, immediately rekey the locks. You might also consider using battery-operated electronic locks that can be easily reconfigured with new codes, should they ever be compromised. Don't use a deadbolt requiring a key on both sides (a.k.a., a double cylinder lock), since it might slow your family's escape in the event of a fire.

Courtesy of Schlage

If windows are not going to be used as fire exits, you can nail or screw them closed, install keyed latches, or cover them with metal grillwork. If the window may act as a potential fire escape, consider using a removable window bar (e.g., Master Lock 266), or quick release, hinged interior bars. An alternative for high-risk windows, sliding glass doors, and storm doors is to cover them with protective security film (e.g., 3M's Prestige).

Due to their privacy and weak construction, basements and garages are often easier points of entry for intruders. To help mitigate these vulnerabilities, install solid-core exterior doors to your basement and garage, and consider using motion-sensor lighting outside. Be sure to include your garage and basement in your home security-system.

Garage and basement doors are easy targets for someone wishing to break into your home.

If you have automatic garage door openers, reprogram them to be different from the factory setting (usually done by changing a couple of internal switches). The same goes for changing the code to the external keypad. Treat your garage remote with the same level of care as you would a house key. Also, if you are guilty of accidentally leaving your garage open at times, consider getting an electronic garage door monitor.

Most garages have manual slide bar latches on each side that can lock the door in place from the inside, making forcing the garage difficult. An alternative to a slide bar is to drill a hole in the track and use a bolt or padlock to keep the door's rollers from moving. Both of these security measures are handiest for use at night or when away on vacation.

A neighborhood watch program is a great way to find neighbors interested in being part of a DP network.

An important part of home security is being part of a community that looks out for one another. In many neighborhoods this manifests as a formal watch program. If your community doesn't have a neighborhood watch program, then at least work to establish an “I'll watch your back if you'll watch mine” mentality with your neighbors.

During certain events (e.g., terrorist threats, contaminant leaks, tornados), your family may be safer confined to a small fortified place within your home.101 Unless you already live in a small home or apartment, it probably makes sense to create a “safe room.” This is a secure area that you and your family can retreat to when a serious disaster threatens. Select a structurally sound room in your home, perhaps a basement or large closet. Ideally, pick an interior room with access to a toilet, running water, and a telephone. Stock the room with a complete set of emergency supplies, including blankets, food, water, medicine, a first-aid kit, flashlights, AM and weather radios, batteries, a cell phone, children's toys, a space heater, and weapons.

Neighborhood watch logo

If, because of your location, you feel that you are at risk of a chemical or biological threat, you may wish to locate the safe room on the upper floor of your home. Gases tend to settle, so the upper rooms are likely to have less airborne contamination. Also, you will want to consider storing some additional items for protection from biochemical hazards:

• Duct tape and plastic sheeting for sealing around doors, windows, and heating/cooling vents.

• A HEPA air filter. When properly sized to the room, HEPA filters have been shown to be effective in removing vapor contaminants and some poison gases.102

• Gas masks or protective hoods, carefully adjusted to fit each family member. Inexpensive disposable respirators, such as N95 masks, can also be used.

• Disposable biochemical protection suits, such as Tyvek F.

For additional details and recommendations regarding sheltering in place and safeguarding against airborne hazards, see Chapter 8.

As with every other preparation, creating a safe room is about weighing risks versus costs. If you live close to an industrial plant, then a room designed to protect your family from chemical leaks probably ranks high on your action list. If you don't live close to a potential biochemical threat, then you may want to tailor the room to better handle other threats—putting your money and efforts toward the most likely dangers first.

Biochemical protection (U.S. Navy)

You may wonder if it is possible to seal the room so well that suffocation becomes a risk. The only documented case found was in 2003 when three Israeli citizens suffocated in a sealed safe room.103 Their mistake, however, was not in over sealing the room, but in burning a coal-fueled heater in the safe room. The heater consumed oxygen as it burned, eventually creating a deadly deficit. Fuel-burning appliances should never be used indoors without proper ventilation. See Chapter 7 for more heating safety recommendations.

There is no evidence to support the myth that a sealed room poses a suffocation hazard.

From the evidence available, it appears to be very difficult to seal a room in your home well enough to endanger your family from suffocation. With that said, it would still be prudent to keep an eye out for signs of oxygen shortage and CO2 buildup. Symptoms include headache, fatigue, shortness of breath, euphoria, and nausea.104,105 If anyone confined to the safe room experiences these symptoms, everyone should immediately seek fresh air.

Given that your home is likely one of your most important financial investments, as well as your family's primary shelter during most disasters, every effort should be made to ensure that it is protected from damage.

Safeguarding your Shelter

1. Minimize hazards in and around your home.

2. Equip your home with safety devices.

3. Adequately insure your home.

Set aside an hour every couple of months to inspect your home for hazards (i.e., things that could endanger your family or your home). Make a checklist, and then work your way through the needed improvements over time—starting with the most important first.

Below are sample outdoor and indoor home hazard checklists. A blank home hazards checklist is included in the Appendix.

OUTDOOR

|

Clear heavy vegetation away from the home. |

|

Remove any dead trees that pose a threat from falling or catching fire. Ideally, even live trees should be far enough away to prevent them from hitting your home, should they fall. |

|

Secure items that might act as flying debris, such as a swing set, barbeque grill, bicycles, deck furniture, or trash cans. |

|

Keep gutters clear to facilitate proper water drainage from the roof. |

|

Inspect and clean chimneys or wood-burning stove vents. |

|

Inspect roofing for loose or worn shingles and degraded seals. |

|

Check gas lines for signs of corrosion or leaks. |

|

Make sure land is properly graded for water runoff. |

|

Store flammables (e.g., gas, paint thinner, cleaners, oily rags) in approved containers, away from heat, and in areas with adequate ventilation. |

|

Check under home for leaks, water-damage, termites, or mold. |

|

Insulate or drain any external pipes (e.g., sprinklers) that might freeze. |

|

If flood prone, raise heating/cooling units above the Base Flood Elevation (BFE) level. |

|

Make sure your house number is visible from the street so emergency vehicles can easily locate the home. |

|

Check that electrical outlets and extension cords aren't overloaded. |

|

Check for frayed electrical cords. |

|

Check that all electrical outlets near sinks are equipped with properly wired ground fault protection. |

|

Connect all sensitive electronics to surge protectors (certified to UL1449 330V). |

|

Use correct wattage light bulbs in lamps and lighting fixtures. |

|

Check all safety devices at least twice a year (e.g., smoke alarms, fire extinguishers, CO alarms). |

|

Inspect underneath sinks and around toilets for leaks. |

|

Ensure that poisonous substances, such as cleaners, pesticides, medicines, and alcohol are locked up or high enough that young children can't reach them. |

|

Eliminate clutter in your home, clearing emergency escape routes. |

|

In earthquake-prone areas: – Place large, heavy items on lower shelves. – Hang pictures and mirrors away from beds. – Secure water heater by strapping it to wall studs. |

Equipping your home with the proper safety devices is the single biggest action you can take to increase your family's chance of disaster survival.

Home safety is about being responsible and protective of what is most precious to you—your life and those of your family. This is one of those rare times when there is a clear right thing to do; and that is to take every reasonable precaution when it comes to keeping your family safe.

Fortunately, there are a small set of safety devices that can significantly reduce your chances of dying from an accident in your home. Safety devices are like insurance; most of the time they cost you money and give nothing more than peace of mind in return. But if tragedy strikes, nothing could be more valuable. Don't skimp on properly equipping your home.

According to the U.S. Fire Administration, fires kill more Americans than all other natural disasters combined.106 Did you miss that? Fires kill more Americans than all natural disasters combined! Forget hurricanes, storms, Earth-destroying asteroids, or volcanic eruptions. If you want to make a big impact in reducing your chances of dying from a disaster, take steps to reduce your risk of dying in a fire.

Fire—a very real threat! (photo by Adam Alberti, NJFirepictures.com)

The National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) reports that an average household will have five fires through the course of a person's lifetime; roughly one every fifteen years.107 Most will be small fires, perhaps a greasy pan in the kitchen, or a candle igniting a tablecloth—easily managed by the homeowner. The odds of having a fire large enough to be reported to the fire department are 1 in 4, and the chances of someone in your household being injured in a fire are 1 in 10.

According to the NFPA, residential fires kill an average of 3,000 Americans each year, and injure another 13,000.108 Perhaps the most tragic part is that 63 percent of residential fire deaths occurred in homes with no working smoke alarms. For your family's sake, take a stand against fire by being thoroughly prepared.

House fires give an average of only three minutes warning!

Early detection is the key to surviving a house fire. Install smoke detectors in the hallways outside sleeping areas as well as in the bedrooms. Keep a minimum of one on every level of your home, even if there are no bedrooms. Put one in the kitchen, as well as the attic, and at the top of the basement stairs. The idea is to put smoke detectors between hazard areas and people areas—providing you with the earliest possible warning. Think about where a fire could start, and where you might be sitting, sleeping, or working; then put a detector between the two locations.

There are three types of smoke alarms available today:

• Ionization alarms—detect flaming, fast-moving fires quickly

• Photoelectric alarms—detect smoldering, smoky fires quickly

• Dual sensor alarms—combined ionization and photoelectric sensors in one unit

Since both types of fires (i.e., fast-moving and smoldering) are possible, you should equip your home with both ionization and photoelectric alarms, or better yet, use dual sensor alarms. Note that alarms using strobe lights rather than sound are also available for people with hearing disabilities.

Smoke detectors can be powered from batteries or from your home's electrical system. House-powered units with battery backup are preferred. If your house was built after 1993, the alarms installed during construction are interconnected alarms—meaning that when one sounds off, it should trigger the others to sound also. This is a great advantage over individual alarms because it ensures that you will receive the greatest warning possible. Did you know that house fires give an average of only three minutes warning for occupants to escape?109

Strobe and voice alarms (courtesy of Kidde)

If you are installing additional smoke alarms after construction, you will likely have to settle for battery-only models since they are much easier to install. Once again, it is best to select units that are interconnectable—now readily available from First Alert, Kidde, and other manufacturers.

The U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission recommends replacing your smoke alarm batteries at least once a year.110 A simple way to remember this is to change the batteries when the time changes in the spring or fall. Always test a smoke alarm after you change the batteries. This is done by pressing the test button on the unit. When you purchase a new smoke detector, you may wish to test the sensitivity of the unit. This can easily be done by lighting a few matches together, blowing them out, and holding them up to the smoke detector. Once the alarm sounds, quickly blow the smoke away or spray a fine mist of water to clear the air.

Children will often sleep through fire alarms.

You might be surprised to learn that children often don't wake up when a smoke alarm sounds. Studies have shown that even at ear-piercing levels, children often remain asleep.110 To overcome this, there are special “voice” smoke alarms available, some even allowing you to pre-record your own voice as the alarm. Voice alarms of this type have been shown to be more effective at waking sleeping children.

Hint: If you accidentally set off the smoke alarm in the kitchen, spray a fine mist of water underneath it, rather than turning off the alarm. Alternatively, kitchen smoke detectors can be replaced with heat detectors to make them less susceptible to triggering from burning food.

It is important to equip your home with fire extinguishers. The NFPA recommends that you keep at least one primary extinguisher (size 2-A:10-BC or larger) on every level of your home. Supplement these with smaller extinguishers in the kitchen, garage, and car to further reduce your family's changes of being injured or killed in a fire.

For general home protection, use ABC extinguishers.

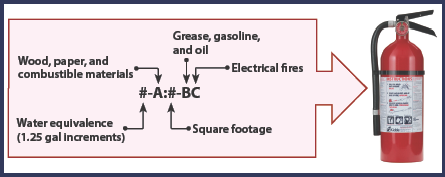

Fire extinguishers spray water or chemicals that either cool burning fuel, displace or remove oxygen, or stop chemical reactions. They must be approved by nationally recognized testing labs, such as Underwriters Laboratory (UL). Fire extinguishers are labeled with an alpha-numeric classification, based on the type and size of fire they can effectively extinguish. It is important to understand the labeling conventions used on fire extinguishers.

Fire extinguisher labeling

The letters A, B, and C represent the type of fire for which the extinguisher is approved: type A is used for standard wood, paper, and combustible material fires; type B is for grease, gasoline, and oil fires; and type C is for electrical fires. A multiclass extinguisher (e.g., BC, ABC) is effective on more than one fire type. For general home protection, use ABC multiclass fire extinguishers. This type of extinguisher is good for nearly any kind of fire except very hot grease fires, chemical fires, and those that burn metals.111

The numbers convey information about the size of fire that the extinguisher can put out. The number in front of the A indicates the number of 1.25 gallon units of water that the extinguisher is equivalent to when fighting standard combustible fires. The number in front of the B rating indicates the square footage of a grease, fuel, or oil fire that the extinguisher can put out. There is no number associated with the C rating.

Caution: Class A air-pressurized water extinguishers (APW) should never be used on grease, electrical, or chemical fires!

For example, an extinguisher labeled 1-A:10-BC is rated to be equivalent to 1 × 1.25 = 1.25 gallons of water for standard combustible fires, and is capable of putting out a grease fire measuring 10 square feet in size.

It is tempting to equip your home with the largest fire extinguishers on the market, but realize that family members must also be able to handle them effectively. A good compromise might be to keep a combination of smaller and larger units distributed throughout the house.

For recommendations regarding the latest fire extinguisher models, consult online reviews, such as the GALT website.112 If the recommended models are not available in your area, simply find a suitable replacement.

A fire extinguisher is only as good as its user. Unfortunately, most people don't know how to properly operate a fire extinguisher—understandable since the average person doesn't have an opportunity to practice. To gain this much-needed and valuable experience, set up a well-controlled practice session. It is worth the cost of an extinguisher or two for you and your family to learn how to put out a fire.

Practicing PASS (photo by U.S. Navy)

Start by picking a suitable location—ideally, a sandbox in the back yard away from everything else. Be absolutely certain that the location is safe. Please don't burn down your house trying to learn how to use a fire extinguisher! Keep a garden hose ready in case you need to put the fire out quickly. Once you have the site ready, build a small controlled fire that is within the capability of your extinguisher. Give each family member a chance to practice putting the fire out.

Have them follow OSHA's PASS method (in tip box).113

PASS Method

PULL—Pull the pin. This will also break the tamper seal.

PULL—Pull the pin. This will also break the tamper seal.

AIM—Aim low, pointing the extinguisher nozzle or horn at the base of the fire. Don't point at the flames, but rather at the material that is actually burning.

AIM—Aim low, pointing the extinguisher nozzle or horn at the base of the fire. Don't point at the flames, but rather at the material that is actually burning.

SQUEEZE—Squeeze the handle to release the extinguishing agent.

SQUEEZE—Squeeze the handle to release the extinguishing agent.

SWEEP—Sweep from side to side, aiming at the base of the fire until extinguished.

SWEEP—Sweep from side to side, aiming at the base of the fire until extinguished.

When fighting a house fire, try to keep your back facing a clear escape path. If the room becomes filled with smoke, leave immediately. Realize that many fires can't be put out with a single fire extinguisher. If you don't get to the fire early, it is better to evacuate your family and let things burn. The primary purpose of having fire extinguishers is to save lives. Property comes second.

If you have upstairs bedrooms, you need a way to escape from them without relying on the main corridors of your home. Some rooms may have direct access to the roof, which can serve as a fire escape by allowing you to go out onto the roof, and hang and drop down to the ground. If a bedroom doesn't have roof access, or if the roof is too high to hang and drop from, you will need to equip the room with an escape ladder. These ladders must be easily accessible. Keeping them buried under fifty pounds of clutter in the bottom of a closet isn't going to help anyone. Escape ladders must be long enough to reach the ground, able to simultaneously support multiple people, and easy to use by those sleeping in the bedrooms.

Courtesy of Bold Industries

Check your windows periodically to make sure they can be easily opened. Windows can become stuck or “painted shut” when not frequently used. Escape ladders (or roof access) are of little value if the windows can't be opened. Breaking out the window glass and trying to climb through it is both difficult and incredibly dangerous.

Each family member must be able to escape without assistance.

Ideally, the windows should be able to be opened by the people who sleep in the bedrooms. If it is a child's room, then he or she should be able to open the window and deploy the escape ladder. This obviously introduces the risk of a child opening the window and falling out. You as a parent have to weigh that risk against the risk of your child perishing in a fire. Many families conclude that emphasis should be placed on falling safety when the child is very young, and then on independent evacuation when the child gets a little older. Whatever methods you choose for escape, practice them so that everyone is clear and confident about their respective actions.

Carbon monoxide (CO) is a deadly, colorless, odorless gas produced by the incomplete burning of fuels such as liquid petroleum, oil, kerosene, coal, and wood.114 Grills, fireplaces, furnaces, hot water heaters, fuel-burning engines, and automobiles all produce CO. If equipment is used correctly (e.g., grill used outdoors), and working properly (e.g., fireplace properly vented), then CO won't build up in the home. However, leaks can occur and judgment can lapse, especially during times of crisis. Having one or more CO detectors in your home is a wise precaution.

Carbon monoxide poisoning is deadly, killing about 200 people in the United States each year.114 Symptoms of CO poisoning include headache, fatigue, lightheadedness, shortness of breath, nausea, and dizziness. If you experience any of these symptoms when operating fuel-burning appliances, such as a range, fireplace, or gas dryer, get fresh air immediately! Then call your fire department and report the situation.

Below are a few rules to follow to minimize your chances of CO poisoning:

• Leave your car running in the garage.

• Burn charcoal inside your home, garage, vehicle, or tent.

• Use gas appliances such as a range, oven, or clothes dryer to heat your home.

• Use portable, fuel-burning camping equipment inside your home, tent, or vehicle.

CO detectors are cheap, small, and very low maintenance—only requiring the occasional battery change. It is especially important to have a unit with battery backup because people tend to use equipment that generates carbon monoxide (e.g., space heaters, generators, cooking grills) when power is interrupted. The best places to put CO detectors are in the locations where the risks reside, such as the garage, near the furnace, and in your safe room.

Most units have a small display that indicates the current CO level, as well as the highest level recorded since the last reset. When a threshold level is exceeded, an alarm will sound. Independent reviews of several units can be found online through Consumer Search.115 Don't worry if you can't find the particular models recommended. Buying name brand units with the features you want will usually serve you well.

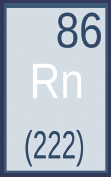

Radon is a colorless, odorless, radioactive gas released by the natural decay of uranium in rock, soil, and water. Once produced, radon rises from the ground and into the air that your family breathes. The gas decays into radioactive particles that become trapped in your lungs. These particles eventually release small bursts of energy that cause lung tissue damage.116

Radon is a poisonous radioactive gas that kills 20,000 Americans each year.

Radon is the leading cause of lung cancer among non-smokers. The gas is attributed with causing about 20,000 deaths annually in the United States. That is more deaths than can be attributed to drunk driving, falls in the home, or drowning.117 It affects about the same number of people as house fires, but with a much higher fatality rate. There are no symptoms from overexposure, and there are no treatments either. Once the damage is done, it's done.

Fortunately, detecting radon is easy and inexpensive. Based on recent testing by Consumer Reports, it is recommended that you use the Accustar Alpha Track Test Kit AT 100.118 This is also the model currently sold through the National Safety Council (NSC). These units are cheap and simple to use—just a small plastic sensor that you place on a shelf in the lowest level of your home. Leave the device out for at least ninety days, and then return it to the laboratory for analysis.

In the event that the home test results indicate levels higher than 2 pCi/L, you should repeat the test. Home tests are not always accurate. If the second test disagrees with the first (i.e., first indicated high, second indicated low), then perform a third test before making a conclusion. If two of the three tests indicate elevated levels (i.e., greater than 2 pCi/L), you should to hire a professional radon test company to confirm the findings and take appropriate action.

Radon testing is not always accurate, so re-testing may be needed.

Remedying high levels of radon requires installing a radon-removal system consisting of a fan-driven, vented system to suck radon away from your home. Correcting the problem can be rather expensive, but given the potential consequences to everyone in the house, there is no question about the necessity of the repair. More information on radon testing and correction is found on the NSC's website.119

Personal aside: My own experience is a good example of the confusion that can come with radon testing. My first radon test result indicated that my home had levels of 5.6 pCi/L, well above the 2 pCi/L maximum. Of course, I became concerned. I placed the second unit at a different point in the same room, and those levels were less than 1 pCi/L. Finally, I repeated the test a third time in yet another location in the room, and it also came back as less than 1 pCi/L—no action required. The question burning in my mind was why did the first unit show such a high level? I ultimately concluded that since I had placed the first unit adjacent to several granite book ends, they must have outgassed some radon into the sensor.

The most important safety items were discussed first: smoke alarms, fire extinguishers, CO detectors, radon detectors, and escape ladders. Consider these safety devices to be on your must-have list. Depending on your particular situation, there are a few additional safety items that you may want to consider.

Radioactive materials can be released into the environment either unintentionally (e.g., nuclear power plant accident), or intentionally (e.g., atomic bomb explosion, act of terrorism). If you feel that your family is in danger of a radioactive threat, then you may wish to equip your home with a radiation detector.

There are two types of radiation poisoning: radioactive contamination and radiation exposure. Radioactive contamination occurs when you come into contact with radioactive materials. Contamination is usually the result of radioactive particulates being inhaled, consumed, or coming into direct contact with your body. Contact with radioactive materials causes tissue and organ damage, and can ultimately lead to death. This is distinctly different from radiation exposure, which is being exposed to the energy that radioactive materials emit—high-frequency rays penetrating the body, such as when you receive an x-ray. Excessive radiation exposure can cause sickness, burns, cancer, and death.

Radioactive contamination is not the same as radiation exposure.

There are pills, such as potassium iodide, that can be taken to help reduce the amount of radioactive contaminant that your body will absorb. However, they will not protect you from radiation exposure. These preventive measures are discussed in greater detail in Chapter 8.

Nuclear power—a potential danger

On average, Americans are exposed to about 300 to 400 milliRems of radiation per year (where a milliRem is 1/1000 of a Rem), most of which is a result of radon, background radiation, and medical imaging.120 The recommended maximum dose is 5,000 milliRems per year, with a total dose of not more than 1,000 milliRems multiplied by a person's age.121

A relatively inexpensive radiation detector that fits on your keychain is offered from NukAlert. It claims to reliably detect radiation levels from 100 milliRems per hour to more than 50 Rems per hour, and can operate for ten full years without a battery replacement. The detector remains active twenty-four hours a day, and sounds different alarms depending on the exposure level.122

If you detect increased levels of radiation, you should immediately contact your local emergency management services. The best way to protect yourself from radiation exposure is to put distance between you and the source. If evacuation is not possible, then put as much solid material (e.g., dirt, concrete, water) as possible between you and the outside world. In the event of radioactive contamination, you should remove your clothing (putting it into a plastic bag away from other people), wash yourself thoroughly, and contact local authorities.123

Courtesy of NukAlert

For additional fire safety, you may want to consider stocking emergency escape hoods and gel-soaked blankets. Escape hoods can help you get through a smoky building without being overcome by toxic fumes. Gel-soaked blankets are designed to help protect from heat and flame as well as treat burns.

When it comes to escaping a fire, time is everything.

In general, both hoods and gel blankets are good products. Their only drawback is that they both require time to equip. And when it comes to a fire, time is everything. Do you really want to take the time to locate and put on your escape hood or blanket? Escape hoods in particular are not easy to put on properly. More often than not, you will be better served by getting out of the house as quickly as possible.

Courtesy of Water-Jel

With that said, if you do find yourself in a room with the only exit clouded with smoke or blocked by heat, the use of an escape hood and/or gel-soaked blanket could very well save your life. You need to assess the likelihood of this situation and prepare accordingly. If you know that evacuating would be time-consuming or require you to pass close to where a fire might originate, then one or both of these products might be prudent investments. Escape hoods, for example, are popular choices for people who work in high-rise buildings. More information about respirators and escape hoods is given in Chapter 8.

If you are trapped in a room with the exit blocked, consider knocking or kicking out the wallboard to get to an adjacent room.

If you have pets in your home, consider getting pet alert stickers. These decals are placed in conspicuous places on your home, usually near the front door, to inform firefighters of how many, and what type of, pets you have in the home. If a fire breaks out while you are away, the stickers will let firefighters know that your home is not empty, and that you wish for them to make every effort to rescue your pets.

Courtesy of Pet Safety Alert

Many people mistakenly assume that the government will step in and help out those who lose property in a disaster. While it is true that mitigating actions are sometimes taken, such as the offering of low-interest building loans, it is generally up to the individual to rebuild and replace what is lost. This is where insurance comes in.

Property insurance is like every other aspect of disaster preparedness. Start by assessing the most likely risks to your home, and then target your insurance to protect from those risks.

Test your knowledge of homeowner's insurance by considering two scenarios involving the same thunderstorm:

Case 1: High winds tear your roof off. Rains pour through the exposed roof and flood your home.

Case 2: Heavy rains flood your yard. The water rises to the point that it floods the ground floor of your home.

Did you recognize that these are considered two very different events by an insurance company? Unless you have specific flood insurance, you are likely not covered against Case 2.

Review your current homeowner's (or renter's) insurance policy to answer a few basic questions.

Basic Home Insurance Questions

1. Are you adequately insured? Are any supplemental structures (e.g., carport, fence, swimming pool) covered?

2. Do you have replacement cost or actual cash value (ACV) insurance?

3. What are your deductibles? Are they reasonable?

4. Are you protected against earthquake or flood? Should you be?

5. Does your insurance provide for temporary housing? What about debris removal?

6. Do you have (or should you have) any special riders covering jewelry, guns, or collectibles?

Based on your answers to these questions, contact your insurance agent to make adjustments. Be sure to ask appropriate questions of your agent, and select the coverage that adequately protects your investment. Remember, as a general rule, it is wiser to have a higher deductible and better coverage than a lower deductible and limited coverage.

Replacement cost insurance will fully replace your belongings. Actual cash value (ACV) insurance will pay you only a prorated amount.

Insist on replacement cost insurance on both your home and contents. If you don't, you could be out many thousands of dollars in the event of a disaster. With actual cash value (ACV) insurance, the insurer could give you only a fraction of the replacement cost due to their assessment of depreciation. Also, remember to adjust your insurance when property values increase or improvements are made.

Make a video of every room in your house. Give a copy to your provider, and keep a copy off the premises.

If you do suffer a loss, your insurance company will require you to provide a detailed description of those items damaged. There are many horror stories of insurance companies failing to pay for items by claiming that the owner never had them and is therefore committing fraud. For your protection, take a video recording of your home and its contents. Walk through every room slowly, verbally discussing all of its contents—noting specific brands, where it was purchased, how long you've had it, etc. Don't forget to include the garage, yard, basement, and attic.

Make at least two copies of the recording. Leave one with your insurance agent, and another one with a friend, family member, or somewhere else outside of the home. Each year when you renew your policy, distribute an updated video. Keeping a video record or your belongings not only protects you, but also makes it much easier for a claim to be processed.

Should your property ever become damaged due to an event covered by insurance, you should immediately document the damage. Once again, the best way to do this is with a video camera. Don't discard anything that was damaged, no matter how unusable, since the remnants could serve to better substantiate your claim.

Keep a record of all conversations that you have with your insurance company, appraisers, contractors, and relief organizations. Request that all agreements, repair estimates, and property appraisals be provided in writing. If you purchase emergency relief supplies, such as clothing or food, or if you have to pay for temporary lodging, be certain to keep all receipts. Provide copies of these receipts to your insurance agent as quickly as possible.

There are two types of evacuations. The first is forced by an immediate threat, such as a house fire, and the second by an imminent, but not yet present, threat such as an approaching hurricane.

In the case of an immediate threat, the rules are simple. Get your family away from the threat as quickly as possible. Don't stop to grab anything that is not absolutely necessary. It is a good idea to identify exits from each room in your home—the primary escape route likely being the main door, and the secondary route through a window. You should practice evacuation with your family, with everyone managing to get out the house without assistance (very young children excluded). Also, agree on a family gathering point outside the home.

Escaping danger (photo by USGS/Don Becker)

You might think that preparation like this will frighten your children. On the contrary, children like to have a clear understanding of the world around them. Many times our sheltering of children to protect them can in fact cause confusion and lead to dangerous misunderstandings. Rather than shoulder all the responsibilities yourself, explain the dangers to everyone, as well as what actions each person is expected to take. Not only does this empower each individual, but it also makes it more likely that your family will successfully escape, even when you are unable to lead them.

Evacuation is decided by one simple question: Is it safer to stay or go?

When a threat is approaching but hasn't yet arrived, perhaps giving you hours or even days notice, you will need to make a calculated decision regarding evacuation. The decision hinges on whether you weigh the danger of staying to be greater than that of leaving. The window of time allowing safe evacuation may be short, so understand that you may be stuck with the consequences of your decision.

As you consider evacuation, take some basic steps to prepare for your possible departure:

• Fully fuel your vehicle and any spare gas cans. Have enough fuel to travel at least 500 miles.

• Identify multiple escape routes from the area being affected. Also, pick at least one alternate retreat location in case traffic flow prevents you from traveling to your preferred one.

• Listen to TV or radio broadcasts to determine when is the best time to evacuate and what the recommended escape routes are.

• Pack your vehicle with supplies, including those you might need for roadside emergencies (see the auto disaster kits in Chapter 13).

If you decide to evacuate, take additional steps to prepare your home:

• Unplug all electronics except for refrigerators and freezers.

• Turn off unused utilities.

• Lock all doors and windows.

• Brace windows, doors, and garage doors as best you can (if appropriate to the threat).

• Write down the GPS coordinates of your home's location. Some disasters are so destructive that even locating your home can be nearly impossible without a set of absolute coordinates.

• Pack your most valuable items in the car. These could be gold coins or old photo albums—you be the judge.

• Let family and friends know when you are leaving and where you will be heading. If you can't convey this information, then consider leaving a note attached to the front door that indicates who you are, where you have gone, as well as contact information of those who might know your whereabouts. A blank “leave behind note” is given in the Appendix for this purpose. Realize that leaving a note like this may make your home susceptible to looting, but that is a price worth paying to give rescuers vital information should you go missing.

• Put on shoes and clothes that will suit you well should your car break down. Be prepared to spend the night in your car.

• Be watchful for washed-out roads, downed power lines, or other roadside hazards. Don't drive into flooded areas! It is very easy to underestimate the depth of water on roadways. If you absolutely must cross a flooded area of still water (not flowing), one person can carefully walk ahead of the vehicle to check for water depth. But this should be done only as a last resort.

Waterproof PVC tubes can be used to hide valuables in the soil under your house.

There are times when you may be forced to evacuate but feel uncomfortable taking valuable items with you (e.g., jewelry, coins, guns). Leaving them behind in an empty house is also undesirable. One option is to bury them in the yard or under the house in small sections of PVC pipe with threaded or pressure-fitted plastic end caps. They don't have to be buried particularly deep, just far enough beneath the soil that they aren't noticeable. This is a reasonable option for locations that might experience looting. Be sure to check the tubes for water tightness before burying them.

Some disasters will leave you without a shelter. Hurricane Katrina, for example, displaced tens of thousands of people from New Orleans. Many of those sought temporary shelter in the Superdome. There were countless subsequent stories telling of crimes of opportunity including robbery, rape, battery, and murder. If even a small portion of them are true, the anarchy described is certainly not something you would wish upon your family.

Hurricane Katrina, 2005 (photo by FEMA/Andrea Booher)

There are many lessons to be learned from Katrina, both by individuals and by our government. Certainly one lesson is that government-provided emergency shelters are less than ideal. They are not the comforting environments that you want to put your family in during times of great stress.

It is almost always better to seek out family and friends first. If you are already part of a preparedness network, someone will likely have the means (and inclination) to put you and your family up for a short time. If you have nowhere else to go, look for a private shelter—perhaps a neighborhood church or civic organization (e.g., Masons, Elks). Your chances of being treated humanely and meeting likeminded individuals are arguably better than they would be at a government-run shelter.

If you are displaced, consider taking some of the following actions:

• Set up a post office box for mail delivery.

• Write to request duplicates of important documents and identification cards that may have been lost, such as birth certificates, social security cards, and driver's licenses.

• Use the public library or other free services to access email and the Internet. This can be a good way to keep family and friends informed of your situation.

Longer term housing needs can be addressed by checking with local homeless assistance programs. The Department of Housing and Urban Development maintains a website with information on homeless programs for various communities across the United States. The website also contains information about receiving counseling and applying for transitional or Section 8 housing assistance.

Homeless Assistance Programs www.hud.gov/homeless/index.cfm

Some of you may wonder why this book doesn't contain details on constructing ad-hoc shelters, such as lean-to's, teepees, and dome shelters. Remember, this guide is targeted toward disaster preparedness, not toward wilderness survival. As such, the decision was made not to fill the pages with detailed plans for building shelters from tarps and twine.

The truth is that, without a great deal of practice, you probably wouldn't be able to build a very good shelter anyway. Also, consider what the chances are of being stranded outdoors without any form of shelter. Keep in mind that your car is a great shelter, much better than anything you can build with makeshift supplies. In the event that you are stranded outdoors without a shelter or a vehicle, it seems inconceivable that you will have the necessary supplies, tools, and blueprints with you to build a protective shelter. From a preparedness standpoint, the best thing you can do is to not put yourself in that very precarious situation.

Make seeking adequate shelter your family's first priority.

Make seeking adequate shelter your family's first priority.

Your home is likely to be the most effective shelter during a crisis.

Your home is likely to be the most effective shelter during a crisis.

Assess the level of protection that your shelter offers to specific threats, and then make improvements to increase that protection.

Assess the level of protection that your shelter offers to specific threats, and then make improvements to increase that protection.

Complete a hazards checklist, removing potential threats to your home.

Complete a hazards checklist, removing potential threats to your home.

Fires kills more Americans than all natural disasters combined.

Fires kills more Americans than all natural disasters combined.

House fires give an average of only three minutes warning.

House fires give an average of only three minutes warning.

Equip your home with as many safeguards as possible, including smoke detectors, carbon monoxide sensors, and fire extinguishers.

Equip your home with as many safeguards as possible, including smoke detectors, carbon monoxide sensors, and fire extinguishers.

Know how to cut off your utilities, and keep the necessary tools close by.

Know how to cut off your utilities, and keep the necessary tools close by.

Set up a safe room in your house that is easy to heat, protect, and seal from chemical and biological threats.

Set up a safe room in your house that is easy to heat, protect, and seal from chemical and biological threats.

Adequately insure your home and car. Elect to have replacement value insurance for your home and contents.

Adequately insure your home and car. Elect to have replacement value insurance for your home and contents.

Follow OSHA's PASS method to extinguish a fire.

Follow OSHA's PASS method to extinguish a fire.

When evacuating, seek family and friends first, but also consider church, civic, and government services.

When evacuating, seek family and friends first, but also consider church, civic, and government services.

If evacuating, stock your vehicle with emergency supplies (see Chapter 13), and be prepared to spend the night in your car.

If evacuating, stock your vehicle with emergency supplies (see Chapter 13), and be prepared to spend the night in your car.

Basic repair and cleanup supplies

Basic repair and cleanup supplies

a. A good set of hand tools

b. Basic home repair materials (e.g., nails, plastic sheeting, duct tape, tarps, PVC fittings, glue, wire, twine)

c. A few home fix-it books

d. Shovel, axe, a wheelbarrow, a heavy broom, and a chain saw—if you can afford one

Home safety equipment

Home safety equipment

a. Smoke alarms

b. Carbon monoxide alarms

c. Radon test kit

d. ABC fire extinguishers

e. Pet fire safety decals

f. Smoke hoods, Water-Jel blankets (optional)