![]()

CARMICHAEL’S REMARKABLE YEAR HAD ELEVATED HIM ALONGSIDE MARTIN Luther King as one of the most influential and reviled figures in American politics. He experienced a disorienting transition from a full-time political organizer into a national icon whose personal celebrity at times overshadowed his political exploits. Carmichael’s notoriety obscured SNCC’s diminishing organizational base and fundraising capacity. A dizzying speaking schedule compounded these difficulties, offering scant time for the organizing necessary to restore SNCC’s faltering political capabilities. For the first time since college, he found himself looking for new political opportunities. Trips to Puerto Rico and Canada whetted his appetite for the kind of international travels that had been Malcolm X’s trademark. Carmichael’s deepening involvement in antiwar protests popularized the chant of “Hell No, We Won’t Go!” into a national slogan and pushed Martin Luther King toward his own, more celebrated, critique against the war. Carmichael increasingly focused his political energies and intellectual interests in pursuit of political terrain that transcended domestic politics. He longed to participate in the undiscovered world of anti-colonial upheavals, political rebellions, and international revolutions. The unquestioned symbol of black radicals in America, Carmichael set his sights on the risky proposition of transitioning into an international revolutionary.1

Carmichael’s most remarkable transition pivoted on his ability to project himself as a thoughtfully outspoken antiwar activist whose influence extended beyond Black Power militants into the world of peace activists and human rights advocates, most notably Martin Luther King. He was just twenty-five, but the pace of history burdened Carmichael with the responsibility of displaying a wisdom and maturity that belied his youth. It wasn’t easy and didn’t always end well. Carmichael spent the first half of the year torn between claiming the mantle of Black Power radical and pursuing the more difficult role of political statesman.

Stokely spent the New Year defending embattled congressman Adam Clayton Powell Jr. in Washington. Powell faced corruption charges even as his loyal constituents defended him as a powerful black politician under unseemly attacks from a racist system. On January 10, inside the House of Representatives, as Powell’s colleagues voted against reinstating him, outside Stokely spoke to a thousand demonstrators protesting the House action. News that Powell’s illustrious and at times infamous career teetered on the brink of extinction attracted a broad section of activists who viewed the development as racially motivated. Carmichael emerged as Powell’s most visible supporter, instructing the large crowd to focus their organizing energies on the White House. “The main cat you focus on is Lyndon Baines Johnson,” said Carmichael, who described the president as an old-school political boss who controlled blacks through the Democratic Party machine. The cure, he insisted, was “not to bloc vote but to black vote.”2

Edward Brooke’s dramatic political ascension paralleled Powell’s fall. Brooke, escorted by Massachusetts senior senator Ted Kennedy, entered the Senate Chamber to a standing ovation from his new colleagues. Brooke and Powell both utilized controversy over Carmichael’s Black Power cry to advance their political ambitions. Whereas Brooke parlayed this advance largely through deft rhetorical maneuvers that repudiated Carmichael’s brand of militancy, Powell alternately praised and teased the young SNCC chairman (as he had often done with Malcolm X) in an effort to assert himself as the pragmatic godfather of the entire Black Power enterprise. Powell boasted to his friends in Congress of having recruited the “entire spectrum of Negro leadership behind me—all the way from Roy Weak Knees (Wilkins) to Whitey (Whitney) Young to Martin Loser (Luther) King to that kook Stokely Carmichael.”3

Powell’s afternoon speech represented a valediction of sorts. In contrast to his demeanor inside the chamber, where he spoke in hushed whispers about personal and ethical lapses, outside the Harlem legend told demonstrators to withhold federal taxes, spread the word about his dismissal around the country, and mark the day as the beginning of a national decline in American political life. “This building,” said Powell as he pointed toward the Capitol with his cigar, “houses the biggest bunch of elected hypocrites in the world.” His ten-minute speech hinted at forming a third party and grand plans to stoke political revolutions that he had neither the energy nor enthusiasm to embark on.4

![]()

AS THE SUN SET ON AN ERA of racial militancy in national politics, Carmichael made his most important professional decision since running for chair of SNCC. He pressed on with a grueling speaking schedule, but on Irv Kupcinet’s Chicago television show, broadcast on Thursday, January 12, he announced he would not seek re-election as SNCC chairman. Publicly, he characterized his decision as a procedural matter, assuring Kupcinet that he had no intentions of retiring from the movement. Privately, an exhausted Carmichael made plans to return to Washington as a full-time organizer. Away from the spotlight, Carmichael met with local Chicago militants and defended his appearance at predominantly white schools as a matter of financial survival, noting that most black groups could not match his speaking fees. Carmichael’s trip to Chicago followed an established routine organized by Cleve Sellers, who often traveled with him. Brief moments of relaxation marked late nights that often drifted into early-morning after-parties. Carmichael’s travel schedule, celebrity, and wandering eye made a steady romantic relationship difficult. Indeed, since Mary Lovelace’s surprise wedding, Carmichael’s personal life seemed adrift in a series of sexual conquests that marked him as an energetic but discreet womanizer.5

SNCC’s organizational woes also continued. Marion Barry, SNCC’s first chairman, resigned from the Washington office in January to begin a journey that would culminate in his election as D.C. mayor in a little over a decade. “I do not think we ought to open a D.C. office,” Stokely observed in an archly written memo, “unless we have some new people who are willing to go there and do some work.” In addition to Washington, he suggested that SNCC either close the Los Angeles office or find a new staff capable of fundraising and reaching out to the black community in Watts. In a flurry of memos, Carmichael tried to make sense of organizational decline while cataloguing deficiencies that extended to San Francisco’s once sparkling fundraising apparatus. The central committee responded with action, suspending the Los Angeles office and dismissing its full-time staff member, closing the Chicago office, and accepting Barry’s resignation. They also wielded more control over Stokely’s speaking schedule. They vetoed an appearance on Firing Line, the conservative William F. Buckley’s public-affairs TV show but agreed to his participation in a Bay Area political conference. Their directive that “Stokely is always to be accompanied by a SNCC staff person at his engagements” was one that Carmichael almost certainly chafed at.6

Carmichael was defining Black Power in an expanded historical context. At a January 16th appearance at Morgan State University in Baltimore, he invoked Frederick Douglass’ message about “power conceding nothing without demand,” as a nineteenth-century version of Black Power. His debt to Douglass transcended their shared interest in political self-determination, dazzling oratory, and knack for earning national publicity. The premier self-made man of his generation (alongside Abraham Lincoln), Douglass innovated a tradition of black political activism that inspired the likes of Marcus Garvey and Malcolm X. If Douglass remained the embodiment of nineteenth-century black political self-determination, Carmichael now claimed his place within this tradition. “This country has been able to make us ashamed of being black,” he observed. “We must stop imitating white society and begin to create for ourselves and our own and begin to embody our cultural patterns so that we will be holding to things that we have created, and holding them dear.” This act of self-definition would lead to a critique of America’s failure to live up to its lofty ideals of freedom and liberty. “You must begin to understand the nature of this country called America, which exploits all other, non-white countries,” he said, offering a clear definition of what many radicals now called imperialism. Stokely had once had an unwavering belief in radical democracy, but he now confronted a growing realization that America, far from being a global beacon of freedom, was in fact an empire. He closed his speech with a generational plea: “When we began to crawl, they sent six million people to an oven and we blinked our eyes. When we walked they sent our uncles to Korea. And we grew up in a cold war. We, this generation, must save the world.”7

Eldridge Cleaver, an ex-convict turned journalist, accompanied Stokely to Morgan that day as part of a writing assignment for Ramparts magazine. Cleaver lingered over Carmichael’s words, laughed at his jokes, and marveled at his ability to establish instant rapport with his audience. A convicted felon and self-confessed rapist, Cleaver had transformed himself into a radical writer. In prison, he had begun a love affair with his lawyer, Beverly Axelrod, who introduced him to leading Bay Area intellectuals, including the editors of Ramparts, a formerly liberal Catholic magazine undergoing an evolution into one the era’s most influential New Left publications. Cleaver’s physical appeal paralleled his budding literary pursuits. Dangerously handsome with the imposing six-foot-two bearing of a former athlete, the thirty-one-year-old Cleaver found a political mentor in the twenty-five-year-old Carmichael. Cleaver’s instant admiration for Carmichael began a professional relationship that would mature into a personal friendship doomed by petty jealousies, organizational rivalries, and mistrust. A member of the Nation of Islam in prison, Cleaver had followed Malcolm’s exit into apostasy. In addition to chairing the Bay Area’s Malcolm X Afro-American Society and turning his rented Fillmore-area brownstone into an intellectual and cultural salon for Black Power activists, Cleaver entered Carmichael’s politically intoxicating orbit.

In late January, Stokely (without Cleaver) visited Puerto Rico. Ella Baker, who had worked with Puerto Rican nationalists in New York in the 1950s, helped arrange the itinerary. Her international vision of the movement had influenced Stokely, and the trip was a realization of this vision. The trip appealed to Cleaver and other Black Power activists eager to discover a shared international history of racial and colonial oppression. On January 24 Carmichael arrived in San Juan to throngs of cheering supporters. Local activists and students representing the Movimiento de la Independencia Puertorriqueña (MPIPR) and the Federación de Universitarios Pro-Independencia (FUPI) organized his tour. Carmichael gave a brief speech at the airport in halting, broken Spanish, before being whisked away to La Perla, a ghetto bordering the ocean. From there he traveled to a local cemetery to visit the gravesite of Pedro Albizu Campos, a legendary hero of Puerto Rican independence, who had died in 1965. Stokely’s entourage reconvened later in Old San Juan, where he read a statement to reporters expressing SNCC’s support for Puerto Rican independence. “Our people are a colony inside the United States,” he said; “you are a colony outside of the United States.” He vowed to resist American military efforts to recruit blacks and Puerto Ricans into the armed forces. “We have experienced with our own bodies and our own blood what this so-called U.S. democracy means,” Stokely declared.8

Carmichael’s visit to Puerto Rico sent FBI and Foreign Service Bureau agents scurrying to keep pace with his travel schedule. Carmichael’s arrival in advance of an island-wide July vote to choose between independence and statehood fanned partisan flames on both sides of the political divide. Wearing sandals, blue jeans, and a wide-brimmed hat that made him look like a brown-skinned campesino, Carmichael led an antiwar student demonstration the next day on the streets of San Juan. Carmichael and over two hundred demonstrators marched from the University of Puerto Rico in Río Piedras to a military induction center in Fort Brook escorted by fifty helmeted riot squad officers. In the barrio of Santurce, dozens of local police offered protection against rock- and egg-throwing anti-Communist hecklers as Carmichael completed a seven-mile trek. Supporters carried a large sign reading “Apoyamos el poder Negro en los estados unidos,” and raucous chants of “Puerto Ricans, Yes—Yankees, No!,” competed against cries of “Puerto Ricans, Yes—Russians, No!” a development Carmichael blamed on anti-Castro Cubans. He gave a brief address at the Fort Brook rendezvous point, assuring the crowd that blacks would “not fight the dirty war in Vietnam,” before rain ended the rally. Carmichael spent the last day of his visit in Mayaguez, where he merged themes of Puerto Rican independence and Black Power. He departed San Juan on an evening flight but not before holding a press conference with independence advocates to announce the signing of a joint alliance forged in a “common struggle against U.S. imperialism” between SNCC, MPIPR, and FUPI, which continued a pattern of establishing coalitions with political outliers.9

Three days after leaving San Juan, Carmichael headlined the final day of a Black Power conference in San Francisco. Participants included Maulana Karenga, whose ubiquitous presence demonstrated Stokely’s ability to consolidate black radicals on the West Coast into a coherent political force. Karenga, the bald and loquacious leader of the Organization Us (which stood for “Us blacks”), was doing important work, forging local bonds with militants who shaped the movement’s grassroots character. Karenga’s offbeat brilliance made his love of African culture and ritualized expression of racial solidarity sometimes rub urban militants the wrong way. His obvious intelligence, puckish sense of humor, and sartorial flair seemed ready made for mass consumption, yet enduring fame would elude him although not his ideas. Overshadowed by the leather-jacketed allure of the Black Panthers, the Organization Us would endure, like jazz, through invented cultural flourishes (primarily through Kwanzaa) that would be adopted by generations of black Americans.10

Another soon-to-be-major West Coast figure, Huey Newton, also attended the conference. He had first met Stokely the previous November. He was brimming with ambitions for his Black Panther Party for Self-Defense that far exceeded the group’s modest resources. Still embroiled in competition with rivals over naming rights, he dreamed of fashioning the type of national political party of which Carmichael himself often spoke.

Carmichael was fresh from Puerto Rico, and his speech explored the conference’s theme of “black survival” through a discussion of the urgent need for national politics attuned to world affairs. Black militants interpreted Governor Ronald Reagan’s political ascendancy as the first step in a nationwide counter-revolution. Carmichael’s speech reminded them that only a lack of political imagination prevented black political control of the Bay Area. “We must begin to think international politics and alliances [and] align ourselves with people of color around the world who are also oppressed.” If Carmichael’s early activism had made him an eloquent proponent of radical democracy, he now railed against conventional notions of American exceptionalism. “We are determined to tear up the pie,” he said, “because to get a piece of that pie one has to be antiblack. SNCC says and is determined to be successful and black.” At the conclusion of his speech, the audience of seven hundred at the Russian Center of San Francisco gave him a standing ovation.11

In between standing ovations in various venues, Stokely struggled to catch up with his voluminous correspondence. He sent personal letters to James Baldwin promising to “get us some Black Power” and expressed more intimate sentiments to female companions from Albany, Georgia, to Paris, France. Carmichael’s good looks, charm, and celebrity afforded him the opportunity for frequent post-lecture romantic encounters with politically engaged female admirers. “All I could say is that I would like to see you again,” he wrote to Gloria Madden, “but that is just impossible because I’ll be in and out of the country from now until the summer (my schedule is already preplanned) and nothing looking near to or by Cleveland.”12

At twenty-five, Stokely regarded his romantic relationships with women as secondary to his primary role as a political activist and organizer. Nonetheless, he devoted considerable energy to maintaining a complex array of romantic entanglements. He regretted his punishing traveling schedule, joked about his fear of commitment, and made plans for future assignations. “I just find myself grasping,” Carmichael confessed to Madden in early February, a description that accurately reflected the emotional and physical toll that life as a national political leader exacted. As emotionally distant with women as he was sexually passionate, Carmichael left a string of paramours in a perpetual state of romantic limbo.13

Carmichael’s burgeoning celebrity attracted a coterie of high-profile personal and professional admirers. Eldridge Cleaver observed Carmichael’s travails through a lens of personal envy and political ambition. Cleaver’s position as a staff writer at Ramparts and other connections allowed him to maintain a relatively secure lifestyle while providing eager white radicals an entrée into black militancy. The tiny Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, for different reasons, attracted both Ramparts and Cleaver. A Malcolm X memorial in February featured a contingent of armed Panthers escorting Malcolm’s widow, Betty Shabazz, to the Ramparts offices. In the confusion that followed, there was a near shootout between police and Panthers. The drama earned Cleaver’s newfound respect for a group of militants eager to recruit him.14

If the Black Panthers appealed to Cleaver’s sense of danger, Carmichael inspired more intellectual ambitions. In the weeks following the Black Panthers’ confrontation with police, Cleaver continued to travel with Stokely on assignment for Ramparts. His Ramparts essay “My Father and Stokely Carmichael,” portrayed Stokely as the leader of a new era freed from the humiliating accommodations of the past. In Cleaver’s opening description of SNCC’s decrepit Chicago offices, the blaring sounds of John Coltrane playing in the background became a soundtrack to hip movement activists. The fleeting presence of Cleaver’s father, who briefly accompanied him to SNCC’s offices in search of Carmichael, served as the article’s opening salvo. Traveling in the middle of a freezing Chicago winter, Cleaver observed and wrote, with a barely concealed mixture of pride and admiration, about Carmichael conducting television interviews, meeting with local militants, and speaking before a predominantly white audience at the University of Chicago. Cleaver had personal reasons for feeling indebted to Stokely, who introduced him to SNCC worker Kathleen Neal. She would, following a whirlwind romance, become his wife. A brilliant speaker, eloquent writer, and accomplished activist in her own right, Kathleen catapulted her way into the front ranks of the Bay Area’s burgeoning political radicalism. As Kathleen Cleaver, she would become the Black Panthers’ communications secretary and one of the best-known female Black Power activists of the era.

“Stokely Carmichael,” wrote Cleaver, “is the first of his stature to finish a college degree.” Cleaver positioned Carmichael as the latest in a black nationalist pantheon that included Malcolm X, Elijah Muhammad, and Marcus Garvey. He praised Stokely’s six years of service in the South as a courageous tour of duty that prepared him to lead a larger revolutionary movement. For Cleaver, the combination of Carmichael’s intellectual agility and mass appeal offered historic opportunities. He held up Carmichael’s plans to tour Africa as part of a necessary cosmopolitanism that soared above the cosmology of the Nation of Islam and the racial separatism adopted by some black militants. Cleaver would take Carmichael’s dictum of establishing “specific alliances on specific issues” as potent collateral against whispers that questioned his close interracial personal and professional contacts. Carmichael’s youthful vitality and unparalleled ability to evoke fear and admiration in intimate and large-scale encounters made a lasting impression on Cleaver. Barely three months out of prison and with a full three years left on his parole, Cleaver requested permission to accompany his hero on a tour of Africa. The request pivoted on Cleaver’s status as a journalist and, if granted, would take him to exotic locales, including Egypt, Liberia, Guinea, Ethiopia, and Ghana. But because of his “short time on parole” and past parole violations, permission was denied.15

Carmichael’s ability to mesmerize white audiences rivaled his hold over Cleaver and black militants. Seven thousand Berkeley students listened in rapt attention to Carmichael’s February 17th account of his years as a local civil rights organizer. After five years of nonviolent direct action, Carmichael said, white authorities could no longer brutalize him without fear of retaliation. “If he touches me, I’m going to try and kill him.” Carmichael challenged Berkeley’s students and the larger New Left to become radical missionaries in an effort to cleanse America’s racist soul. “Fight to take over,” he admonished, “and fight to find white leaders who are civilized.” Political transformation required a new generation to “change the whole society,” which included “taking over the corporate structure and running it.” The next morning, he fielded questions from over a hundred participants who attended an invitation-only Black Power conference held at the Masonic Temple in Los Angeles. Then he flew to New York to attend a Malcolm X memorial.16

Following the Malcolm X commemoration, Carmichael left the country for a brief speaking tour of leading Canadian universities. At Montreal’s McGill University, on February 23, he spoke before an audience that found his combination of physical appeal and intellectual provocation irresistible. The next day, the Trinidadian born, one-time Trotskyite, and life-long Marxist historian C.L.R. James joined dozens of blacks, among a sea of white students, at Carmichael’s February 24 lecture at Sir George Williams University, also in Montreal. James’ eclectic writings on Haiti, class struggle, and cricket made him an intellectual hero for radicals drawn to his imaginative blend of intellectual theory and revolutionary politics. James had been deported from the United States to England in 1953 because of his radical politics, but his influence extended to black militants in Detroit, Caribbean revolutionaries turned statesmen, and newly elected African rulers. Carmichael’s speech, demeanor, and charisma impressed James, who wrote to him shortly after. Old enough at sixty-six to be Stokely’s grandfather, James identified Black Power as the culmination of mass political energies harnessed by world historic figures including Marcus Garvey, George Padmore, and Frantz Fanon. Thus began an occasional correspondence and cordial political relationship that found the elderly Trinidadian offering the wisdom of a lifetime spent studying historical materialism to Carmichael. The standing ovation that ended Carmichael’s presentation rivaled the wild cheers and large crowds that greeted his appearance, the same day, at the Université de Montréal.17

From prestigious Canadian universities, his punishing schedule continued into March, with a swing through western Pennsylvania. There he spoke at two universities and a church in Pittsburgh (where he invoked a popular chant—“Beep, Beep, Bang, Bang, Ungowwa Black Power”—that young people would continue to repeat years after his lecture), followed by a lecture at Saint Vincent College in Latrobe. His March 2nd itinerary in Pittsburgh offered an instructive view of his typical speaking schedule in major cities. Appearances at the University of Pittsburgh and Point Park Junior College were supplemented by a press conference during the day and capped off by an evening, standing-room-only lecture at Ebenezer Church in front of a predominantly black crowd of several thousand.18

As Carmichael spoke in Pittsburgh, Lyndon Johnson returned to the scene of one of his finest hours as president. Johnson’s unannounced visit to Howard University reaffirmed his commitment to racial justice in a symbolic effort to recapture the urgent momentum that galvanized his historic commencement address almost two years earlier. “I don’t want to turn back,” he promised a surprised crowd of students, faculty, and staff on hand to celebrate Howard’s centennial anniversary. Symbolically, Johnson’s appearance suggested that the president’s faith in the struggle for civil rights remained steadfast. “I have come back to Howard today to renew my commitment to that task,” he pledged, “and to tell you that so long as I live, in public or private life, I shall never retreat or amend that commitment.” The widely covered speech received warm applause from Howard’s audience and showcased the political sophistication of a generation of black college students intelligent enough to support the starkly divergent visions of American democracy of both Johnson and Carmichael.19

Carmichael returned to Atlanta for a few days. There, he lent support to members of NOI Temple No. 15, who had recently engaged in a violent altercation with the police. Then he presided over a grueling SNCC central committee meeting, where long-festering wounds over the increasingly erratic behavior of Atlanta Project members reached a boiling point. On Saturday, March 4, the central committee convened to discuss the recent firing of two Atlanta Project staffers, a maneuver sanctioned by Carmichael and Cleve Sellers to end disputes over the proper use of SNCC-owned vehicles. Because of SNCC’s personal intrigues there, staff referred to Atlanta as “Peyton Place,” after the TV soap opera. Jim Forman clung to a desperate hope, “that despite our fumblings and our fucked-up internal situations,” SNCC remained the radical black movement’s political face, albeit one undergoing a painful re-evaluation.20

For Carmichael, SNCC’s transformations meant that he had to dramatically curtail speaking to white audiences. He said, “Personally I have three more engagements before white audiences” before he would retire from the college lecture circuit. Having reached “the conclusion that SNCC will not move into the black community and begin fund-raising until we go broke,” he scheduled twenty-two speeches at black colleges over the next two months in advance of a May staff meeting. Carmichael characterized his visit to Pittsburgh, where he stayed an extra day organizing an Afro-American club, as a model for his future speaking engagements. He had concluded that SNCC had “to direct our attention to black people only.” He also announced plans to roam Alabama, Mississippi, and southwest Georgia in hopes of lending his experience to ailing projects. “I’m tired,” he lamented, “of being a showpiece.” These last remarks were partially fueled by Carmichael having observed vendors hawking one-dollar buttons of his likeness that grinned when shook, an image that sent staff into convulsive laughter.21

And then on March 14, at Lafayette College in Easton, Pennsylvania, the personal and political collided. Stokely delivered what would have been a standard stump speech decrying American involvement in Vietnam, except that his appearance came the day after his local draft board had changed his classification from 1-Y to 4-F, exempting him from military service.22

With his own military service resolved, Carmichael continued to link Black Power and Vietnam as part of a radical critique of American racism that defined the nation as an empire whose imperial ambitions threatened humanity’s future. Martin Luther King was perhaps the individual most affected by Carmichael’s high-profile antiwar message. That spring King definitively amplified Carmichael’s seasoned antiwar rhetoric in a measured, resolute speech that sent shockwaves across the nation and around the world. King’s April 4th address at New York’s Riverside Church lent international stature and moral clarity to antiwar speeches that Stokely had defiantly delivered as SNCC chairman. At Riverside, King balanced his personal disappointment in American democracy with weary hope. “The world now demands,” he pleaded, “a maturity of America that we may not be able to achieve.” King’s words now resound with an authority that would in later years swell. But, shortly after the Riverside speech, he found himself in the uncomfortable position of having to disabuse some observers that he was simply echoing Carmichael’s antiwar stance. He needn’t have worried. King’s peace advocacy impressed future historians as a daring rejection of the status quo, just as association with Black Power would muffle Carmichael’s stridently eloquent antiwar advocacy. King’s bold antiwar talk made efforts to negatively link him to Carmichael—whispered since the Meredith March—easier for critics who correctly identified both men as political revolutionaries. “If Negroes hope to continue to make progress, they had better get responsible leadership and repudiate the Kings and Carmichaels,” warned the Chicago Tribune on April 6.23

At Tennessee State University on Friday, April 7, Carmichael urged four thousand students to wake up from their political stupor and fight for black rights. He detailed the difference between institutional racism and individual prejudice; the real enemy was not prejudiced individuals but racist institutions: “You’re going to fight institutionalized racism; the reason it is able to perpetuate itself is because of power. Not love. Not morality. Not nonviolence, but power. And if you’re going to check it, you need power to counteract the power that is used to perpetrate . . . institutionalized racism in this country. That’s Black Power.”24

His appearance at the historically black school represented a triumph of self-determination, after three thousand students had signed petitions urging administrators to uphold freedom of speech over fears of subversion and let him speak. “We must become masters of our own terms,” he said. Only black people could define themselves. “We are not savages,” he told the room full of black students. “We are not culturally deprived. We are not apathetic. We are not lazy [but] beautiful, black, intelligent, aggressive people,” he proclaimed to applause.25

He chided students for ignoring a political revolution gripping the entire globe “and you don’t even know how democracy works in your own little Nashville.” The more he ridiculed them, the more they cheered. “You ought to organize and take over this city, but you don’t do it because you don’t want power.” The day before, Carmichael briefly conferred with Martin Luther King, in town to address Vanderbilt University’s “Impact Symposium.” The sight of Carmichael and King together offered a jarring image of the potential for black social and political transformation. Carmichael introduced King to his new friend Eldridge Cleaver, who had accompanied Stokely to Vanderbilt. Cleaver would remember the moment as a time when Carmichael’s mere presence “threw the entire state into an uproar.”26

On Saturday, Carmichael addressed a capacity crowd at Vanderbilt, where he delivered a radical critique of American democracy. It was based on a Massachusetts Review essay on black power he had written with former NAG member and Hilltop editor Michael Thelwell. His easy humor remained intact, however, as he only half-jokingly ordered “the honkies of The Banner,” the conservative Nashville daily, to “leave because you will not begin to understand the lecture that I am about to give.” That evening, unrelated bedlam broke around Nashville’s black Fisk University, where Carmichael had spoken the previous day. The violence left three students wounded by gunfire, dozens injured, and almost one hundred in jail. Cries of “Black Power!” pierced through a confrontation between Fisk students and riot police, which had begun as a Saturday evening demonstration over the arrest of a black student at a nearby restaurant and escalated into a small riot.27

By Sunday, violent flashes spread to Tennessee State’s campus, leaving Nashville in a confused state of spreading panic linked together by Carmichael’s presence. Rioting in the wake of his brief visit fulfilled the warnings of the Nashville Banner, which vilified Carmichael as an “interloper” and “firebrand” in advance of his appearance. The Nashville Tennessean defended Carmichael as a test of First Amendment freedoms, noting that he represented merely the most powerful voice of a movement the region ignored at its own peril. Shades of Atlanta hovered over the Fisk disturbance after one local black leader practically accused Carmichael of igniting the flames of Nashville’s riot through militant proxies. Carmichael’s volatile image contrasted with his recent appearance on WPLN’s Nashville Forum, where he chatted amiably about independent politics, quoted the Book of Job to explain black people’s right to self-defense, and deliberated on Frantz Fanon. One panelist on the show lamented that his militancy frightened white liberals eager to confront America’s racial sins. “Well then, if you want to make up for the sins, you go to the sinners,” replied Carmichael. The New York Times responded to the Nashville disturbance by writing SNCC’s epitaph, describing the group as financially insolvent and Carmichael as a “romantic young man who busies himself speaking mainly to white audiences who are intrigued by his inflammatory rhetoric.”28

If Nashville showcased Stokely’s romantic side, a speech in New York soon hinted at a newfound revolutionary pragmatism. On Saturday, April 15, King, Carmichael, and hundreds of thousands of others marched from Central Park to the United Nations, as part of the Spring Mobilization to End the War in Vietnam. The two men’s appearance together marked them as friendly political adversaries whose seemingly disparate constituencies united in opposing the Vietnam War. The two shared top billing with Harry Belafonte, Dr. Benjamin Spock, and the event’s organizer, James Bevel, as speakers in front of the UN. If Carmichael’s imaginative blend of civil rights, Black Power, and Vietnam elicited anger, King’s efforts inspired reactions that ran the gamut from betrayal to rage to condescension. Without mentioning him, the NAACP repudiated the notion of linking civil rights and peace movements as a “serious tactical mistake,” while King’s fellow Nobel laureate Ralph Bunche publicly urged him to resign from the movement or maintain a decorous silence on Vietnam.29

In New York, Carmichael linked arms with King, Spock, Belafonte, and Bevel in the march’s front ranks, which led swelling numbers of demonstrators that city officials put at one hundred thousand and rally organizers claimed as four times larger. It was the largest peace demonstration in American history. Three thousand local police officers were joined by the less visible presence of FBI agents and surveillance teams who observed marchers gather at Central Park’s Sheep Meadow destined for the United Nations Plaza. Two more Central Park staging areas bustled with activity in advance of the noon start time as demonstrators listened to folk singers, rock and roll bands, and poetry. Dozens of Cornell University students burned their draft cards in an act that marked a symbolic shift in the public rejection of war and inspired a hundred more young men to join them in creating an improvisational fire they kept contained to a coffee can.30

At noon, a cavalcade of demonstrators began a four-hour procession toward the United Nations. Black nationalists from Harlem, white housewives from Westchester, poets from Greenwich Village and the East Village, and college students from all over joined the march route. Counter-demonstrators hurled eggs and paint at protesters but were kept largely in check by police. Carmichael and King walked along the front line of the march protected by peace marshals deployed by Ivanhoe Donaldson, in a reprise of security measures that dated back to Selma.

From the platform erected at the United Nations Plaza, Carmichael repeated his antiwar proclamations amid chants of “Black Power!” He was serving, for the first time since the Meredith March, as a powerful warm-up act for Dr. King. “I am here today,” he began, “not just as the chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, not just as an advocate of black power, but as a black man [and] human being who joins you in voicing opposition to the war on the Vietnamese people.” Invoking Malcolm X, he questioned the values of a nation willing to wage war in the name of liberty and deploy American military strength against the Third World under the guise of freedom. “We black people have struggled against white supremacy here at home,” observed Carmichael. “We therefore understand the struggle against white supremacy abroad.” Carmichael declared public support for “Dr. Martin Luther King’s stand” and reminded listeners that his Nobel Prize showed “that at least in Sweden, the connection between ending war and ending racism is clear.” He challenged his critics to consider a Biblical quote: “What would it profit a man to gain the world and lose his soul?” Carmichael juxtaposed the moral clarity of the Nuremberg Trials in the aftermath of the Second World War with contemporary silence regarding Vietnam. “Where is the voice of conscience today?” he wondered. “We have not only a right to speak out. We have an obligation.”31

As he often did in such large public settings, Carmichael assumed the role of professor. Here he was delivering a seminar on American imperialism, a system that enabled the nation to casually smother anti-colonial impulses even as it professed its commitment to spreading democratic freedoms around the world:

We maintain that America’s cry of “preserve freedom in the world” is a hypocritical mask behind which it squashes liberation movements which are not bound, and refuse to be bound, by the United States’ cold war policies. We see no reason for black men, who are daily murdered physically and mentally in this country, to go and kill yellow people abroad, who have done nothing to us and are, in fact, victims of the same oppression. We will not support LBJ’s racist war in Vietnam.32

Carmichael chastised Ralph Bunche “up on the 38th floor of this building” who “once marched against police brutality in Selma, Alabama” but “today condemns those of us who speak out against the war.” Bunche’s hypocrisy mirrored the president’s, since LBJ continued to talk of peace “while Napalming Vietnamese children.” The massive size of the gathering offered an alternative to this political misery: “In your great numbers lies a small hope.”33

His speech delivered words of fire but extended a political olive branch to those brave enough to recognize the sacred political ground shared by peace activists and Black Power radicals. Carmichael judged the Mobilization an enormous success. He was impressed by the massive turnout, which convinced him that young people held the key to transforming American society. Perhaps the sea of faces evoked a tinge of nostalgia in Stokely, who effusively praised the gathering in private to the point of discussing the possibilities of interracial democracy. He found the entire event moving enough to write to Lorna Smith that young people, both black and white, offered American society its last best hope. With trusted white friends and colleagues, Carmichael still held out hope for a revolutionary future that featured interracial coalitions.34

Carmichael and King met later that night at Harry Belafonte’s sprawling New York City apartment. Their still-warm personal relationship smoothed over rough patches of conversation that found Stokely interpreting King’s Riverside address and UN appearance as being influenced by his own antiwar posture. Carmichael reveled in the fact that his contrarian advocacy of Black Power and an end to the Vietnam War could jolt King into action and found it too irresistible, at least in private, not to mention it personally. Carmichael’s performance softened some of his most ardent critics inside the movement. Stanley Levison, whose enmity had raged since Atlanta’s riot, conceded that Carmichael’s efforts at rapprochement affected the demonstration positively.35

The African-American photographer Gordon Parks visited Carmichael in the Bronx shortly after his United Nations speech as part of a Life magazine profile. Carmichael touted King’s Vietnam stance as an example of their shared recognition of common foes. “The people who support the war in Vietnam are the same ones who keep their foot on the black man’s neck in this country. Bigotry and death over here is no different from bigotry and death over there.” Carmichael described his antiwar stance as the logical outgrowth of a Black Power philosophy that transcended purely racial appeals to political change. “I suppose it’s pride, more than color, that binds me to my race,” he told Parks. “And I’m learning that the concern for blackness is necessary, but that concern has to go further than that to reach anyone who needs it.” He echoed Courtland Cox’s line about blackness being necessary but not sufficient. Recognition of his own mortality hovered over his conversations with Parks. “Mississippi taught me that one’s life isn’t too much to give to help rid a nation of fascists,” an experience that allowed him to view the prospect of death as the necessary corollary to a lifetime of revolutionary struggle.36

Carmichael’s insouciance struck a chord in Parks. Parks (an equally adept writer, memoirist, and raconteur) and Carmichael bonded over shared reputations as mavericks. “Stokely gives the impression,” Parks observed, that he could “stroll through Dixie in broad daylight using the Confederate flag for a handkerchief.” Carmichael’s unshakable antiwar position evoked conflicting feelings in Parks, whose son served as a tank gunner in Southeast Asia. Parks wondered which of the two young men’s fight was more just. Finding “no immediate answer,” he concluded that, “in the face of death, which was so possible for the both of them, I think Stokely would surely be more certain of why he was about to die.” Stokely Carmichael had become, for Parks and millions of other black Americans, a surrogate son.37

![]()

NEAR MIDNIGHT ON THE LAST SATURDAY IN APRIL, Martin Luther King telephoned Stokely at his Atlanta office. A night owl who operated on a few hours of rest, Carmichael waged a losing battle with sleep and keeping up with his administrative duties. In private Carmichael and King shared a teasing repartee that took the edge off of their mutually stressful lives. After exchanging pleasantries, King invited Carmichael to attend Ebenezer Church services the next day. Performing his expected role in their usual banter, Carmichael initially balked before King’s relentless pleading wore him down. “Something special happening, Reverend?” asked Carmichael. “Well . . . I’ll be preaching,” replied King. Carmichael teased that he enjoyed King’s ability to “make me tap mah feets,” but this joke fell on deaf ears. “I really do want you to be there tomorrow,” said King, “because . . . tomorrow . . . before my congregation . . . I’ll be making my statement on the war.” A pause of over thirty seconds followed before Carmichael finally spoke in a tone barely above a whisper. “I’ll be there, Dr. King. I’ma be in the front row of that church.” After hanging up, Carmichael immediately contacted Cleve Sellers to inform him of their new plans.38

Unusual circumstances beyond Carmichael and Sellers’ appearance on Ebenezer’s front pew marked the Reverend King’s Sunday morning sermon. Reading from a prepared text, King mocked America’s narrow application of nonviolence. “There is something strangely inconsistent about a nation and a press that will praise you when you say be nonviolent toward Jim Clark,” said King, referring to Selma’s brutally racist sheriff, “but will curse you when you say be nonviolent toward little brown Vietnamese children!” He praised Muhammad Ali as a courageous dissenter who chose personal conscience over material splendor even at the risk of imprisonment. King’s elevation of Ali as a youthful champion of peace implicitly acknowledged Carmichael’s trailblazing anti-war activism. Ironically, both Ali and King would achieve a kind of romantic identification as antiwar icons in a manner that would elude Carmichael. King’s passionate speech injected an air of mournful outrage into the national debate over Vietnam and drew stark lines between competing visions of American democracy that his political activism had helped creatively blur over the past decade. Carmichael led the entire congregation in a standing ovation.39

The next day, Stokely’s best friend was undergoing a rite of passage for young men their age. Cleve Sellers was to be inducted into the army, and Stokely accompanied him. Friends and confidants, the volatile Carmichael and the even-tempered Sellers drew strength from their contrasting personalities. Just as Stokely masked an imposing intellect behind a cool pose, the deceptively fierce Sellers hid a quiet rage behind a placid, at times stoic, exterior. At the induction center, Sellers remained standing when told to step forward and made national news by refusing to serve in the army. Carmichael found the fact that sixteen SNCC workers had been called up by local Selective Service suspicious and told reporters that none of them, including Sellers, would serve. “They are drafting Negroes to commit genocide against their race,” Stokely said.40

Four days later, Carmichael released an internal exit report from his year as SNCC chairman. “We have been able in the last year to change the milieu of the country in terms of how it views Civil Rights,” he wrote. “Our job now IS TO ORGANIZE.” The report advocated independent politics, community control, and grassroots organizing in urban ghettoes and rural hamlets as part of an expansive freedom agenda.41

Carmichael’s bold talk reverberated to the upper echelons of American politics. On the Friday after Cleve Sellers refused military induction, members of the House Armed Services Committee pelted Assistant Attorney General Fred Vinson with questions about why Carmichael had yet to be prosecuted for sedition. Vinson’s defensive admission that Carmichael’s “outrageous” antiwar speeches did not cross legal bounds was met with skepticism. Louisiana representative F. Edward Hébert suggested forgetting the First Amendment to “show the American people that the Justice Department and Congress were trying to clean up this rat-infested area.” After pointing out the Constitution’s inherent protections of dissident speech, Vinson was asked by another member for his personal opinion of Carmichael’s now famous “Hell no, we won’t go set!” catchphrase. He replied, “I think it is an outrageous statement that is under the protection of the First Amendment in the circumstances he made it.” Vinson’s citing of precedent dating back many decades to Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes did little to placate impatient politicians. In an ominous sign that elected officials now regarded them as partners, committee members singled out Carmichael and King by name throughout the hearing. “How can the Carmichaels and Kings stand before the American people and incite violation of the law while the Justice Department stands idly by?” demanded Hébert. With a rhetorical sleight of hand, King’s critics attempted to discredit him through association with Carmichael.42

Carmichael’s new public association as King’s unlikely political partner on the subject of Vietnam coincided with the end of his tenure as SNCC chairman. SNCC’s annual elections during the second week of May clarified Carmichael’s organizational status, with H. Rap Brown as the new chairman along with two new executive committee members. Outside Paschal’s Motel in Atlanta, Carmichael addressed reporters about the administrative change, introducing Rap Brown, program director Ralph Featherstone, and executive secretary Stanley Wise, who replaced the gravely ill Ruby Doris Smith Robinson. Carmichael sat next to a dour-looking Brown, whose sober demeanor masked nervous energy over assuming national leadership at the tender age of twenty-three. Sporting a denim jacket, sunglasses, a medium-sized afro, and a mustache that drooped over the sides of his mouth, Brown looked the part of a Black Power revolutionary. His distinctive Louisiana drawl lent his urbane expressions of racial solidarity with far-flung African independence movements a measure of folksy authenticity. It also hid political shortcomings. Sensing that reporters mistook Brown’s anxiety for meekness, Carmichael preemptively set the record straight. “People will be happy to have me back when they meet him,” he cracked.43

The slightly awkward press conference mirrored Brown’s transition to the chairmanship. Carmichael’s enormous star power overshadowed Brown’s initial efforts to establish a public identity as well as SNCC’s plans to expand its civil rights portfolio to include human rights and increase its political reach to the international arena. Brown, perhaps too eager to prove himself, would soon indulge in over-the-top rhetoric that seemed designed to out-Stokely Stokely.44

While Rap Brown became SNCC’s new chairman, the FBI’s focus remained on Carmichael. On Tuesday, May 16, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover released portions of the director’s congressional testimony, made three months earlier, to the news media. Hoover accused Carmichael of being under the direct control of communists and anti-American subversives. New allegations charged Carmichael with maintaining contact with communist front groups. FBI phone lines buzzed with reporters clamoring for more information, only to be told that Hoover’s testimony stood “on its own two feet and we can add nothing.” Reporters confronted Carmichael in Grand Rapids, Michigan, about Hoover’s charges. Instead of the expected fireworks, Carmichael calmly requested that Hoover prove the charges, adding that the FBI director, who was seventy-two years old, should retire.45

Hoover’s testimony overshadowed shocking reports of a police raid at two homes in suburban Grand Rapids, where investigators found weapons linked to a plot by white supremacists to assassinate Stokely. FBI investigators picked up chatter about harming Carmichael from a group stockpiling grenades, artillery shells, fourteen sticks of dynamite, and two submachine guns. The bureau claimed no jurisdiction over the matter publicly but privately found enough plausible evidence to suggest those arrested posed a threat to Carmichael’s safety. A police escort transported Carmichael from the airport to his hotel, and reinforcements were on hand for his appearance at Fountain Street Church in downtown Grand Rapids, where an audience of almost two thousand listened to a speech bursting with references to Frederick Douglass, Malcolm X, and Jesus. Carmichael capped off his evening by visiting Grand Rapids’ black community, where he spoke at the Trinity Church to a small group of teenagers, still buzzing over reports of thwarted assassination plots, suburban arsenals, and FBI vendettas.46

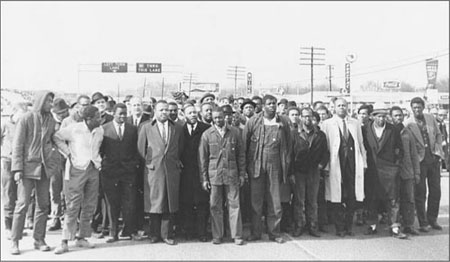

Selma, March halted at the bridge, March 9, 1965 (Stokely Carmichael, far left; MLK, Jr. fifth from left). The Jack Rabin Collection on Alabama Civil Rights and Southern Activists, Box 4, Items 050. Courtesy of Historical Collections and Labor Archives, Special Collections Library, The Pennsylvania State University.

Civil rights leaders Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. (left) and Stokely Carmichael (right) participating in a voter registration march after originator James H. Meredith was shot on June 6, 1966. Photo by Lynn Pelham/Time Life Pictures/Getty Images

Stokely Carmichael speaking at a meeting at a small church building. Jim Peppler/ Southern Courier/ Alabama Department of Archives and History, Montgomery, AL.

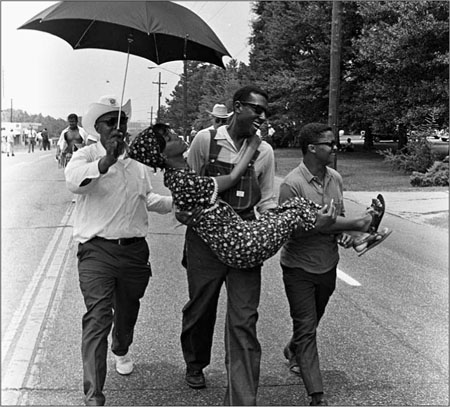

Stokely Carmichael carrying a young woman down the road during the Meredith March in Mississippi. Jim Peppler/ Southern Courier/ Alabama Department of Archives and History, Montgomery, AL.

Stokely Carmichael addressing a crowd in front of the Neshoba County Library in Philadelphia, Mississippi, during the “March Against Fear” begun by James Meredith in June 1966. Jim Peppler/ Southern Courier/ Alabama Department of Archives and History, Montgomery, AL.

Stokely Carmichael speaking to an audience during the “March Against Fear.” Jim Peppler/ Southern Courier/ Alabama Department of Archives and History, Montgomery, AL.

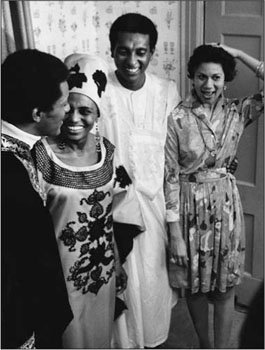

Humor enlivens wedding preparations as the family gets together. Enjoying Carmichael’s jokes are (from left) his mother, his sister, Judy, and Sinclair Greenidge, Stokely’s cousin (1968). Courtesy Johnson Publishing Company, LLC. All Rights Reserved via AP Images.

Stokely Carmichael speaks in London in July 1967. Photo by Bentley Archive/Popperfoto/Getty Images

Stokely pals with Gloria Richardson at his wedding, while Guinean Ambassador Achkar Marof maintains the light mood (1968). Courtesy Johnson Publishing Company, LLC. All Rights Reserved via AP Images.

Stokely Carmichael walking down Auburn Avenue during Martin Luther King, Jr.’s funeral procession on April 9, 1968. Jim Peppler/ Southern Courier/ Alabama Department of Archives and History, Montgomery, AL.

Stokely Carmichael with his wife Miriam Makeba and others walking in Martin Luther King, Jr.’s funeral procession on April 9, 1968. Jim Peppler/ Southern Courier/ Alabama Department of Archives and History, Montgomery, AL.

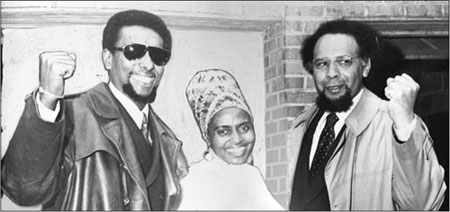

Stokely Carmichael is shown with his wife Miriam Makeba and attorney Howard Moore after testifying for the Senate subcommittee in 1970. Photo by Afro American Newspapers/Gado/ Getty Images

Carmichael speaks during an engagement at his former school, Bronx Science High School, in New York in December 1985. Photo by David Fenton/Getty Images

On Thursday, amid the fallout from Hoover’s charges, Carmichael made a brief stop in Jackson, Mississippi, to attend the funeral of Ben Brown, a student activist killed the previous week during rioting at Jackson State. Stokely was en route to an afternoon visit to Southern University in Baton Rouge. Investigators from Mississippi’s secret Sovereignty Commission snapped photos of Carmichael, Sellers, Willie Ricks, and local Tougaloo activist Howard Spencer at Jackson’s airport. Carmichael knew Ben Brown, a highly regarded civil rights worker, from SNCC’s Summer Project. The funeral reunited Stokely with Mississippi activists Owen Brooks and Lawrence Guyot, who joined over seven hundred mourners at the Masonic Temple on Lynch Street, where they gathered in stifling heat to eulogize a fallen hero. Carmichael arrived just in time to hear Brooks preach a sermon that called for a political reckoning to cleanse the Magnolia State. Carmichael remained composed throughout the service, but the funeral undoubtedly evoked painful memories of Jonathan Daniels and Sammy Younge and perhaps increased a growing preoccupation with his own mortality.47

![]()

IF STOKELY’S STATUS AS A NATIONAL LEADER complicated his hopes to resume grassroots organizing, events in California would soon make it impossible. Huey Newton’s brash decision to send an armed convoy of Black Panthers to the State Capitol in Sacramento on May 2 triggered bursts of panic and near hysteria that simultaneously burnished the young organization’s celebrity and jeopardized its already slim chances of longevity. Newton’s gamble poised the Black Panthers on a tightrope between daring improvisation and reckless bravado that mixed threats of violence with the exhilarating spectacle of street-corner toughs as political revolutionaries. The Black Panthers imagined a world not yet in existence, but one that they thought they could will into being. Newton’s subsequent drafting of Carmichael into the BPP continued a pattern that marked the Panthers as visionaries daring enough to confer the rank of field marshal on Carmichael, with a public commission to “establish revolutionary law, order and justice” over the United States.48

A New York Times article in the late summer resuscitated the waning buzz from the group’s Sacramento adventure. “The Call of the Black Panthers,” by Ramparts’ assistant managing editor Sol Stern, featured a soon-to-be-iconic photo of Newton. Wearing an open white dress shirt and a black leather jacket, Newton sat pensively holding a rifle in one hand and a spear in the other, with African shields carefully strewn across the floor. The image evoked poetic juxtapositions between the past and present, the modern and the ancient, that suggested black revolutionaries needed a potent knowledge of history and politics. For Stern, the Panthers’ limited impact on the Bay Area’s civil rights scene made them less of a political phenomenon than a sociological one. Against the backdrop of national urban civil disorder, the Panthers—with their melodramatic statements, bombastic posture, and dead serious swagger—demanded attention. The article lingered over Newton’s photogenic looks and smoldering intensity, showcased co-founder Bobby Seale’s charisma, and documented the Oakland Police Department’s enmity. With characteristic brio, the Panthers inflated membership numbers, spoke of mounting a global revolution against American imperialism, and convened sparsely attended rallies.49

The Black Panthers drafted Carmichael into their organization that summer, identifying him as the most important radical of his generation. Muhammad Speaks, perhaps wistful for the days when Malcolm X struck fear into the white mainstream, cheerfully observed that America was “quivering under the searing lashes” of Carmichael’s words.50

June 11 found Stokely in rural Autauga County, next to Lowndes and forty miles outside of Montgomery. At an outdoor meeting, his typical exhortations advocating self-defense proved too much for the police, who arrested him. The arrest coincided with the premiere that evening of an NBC news documentary, “After Civil Rights—Black Power.” Footage of Stokely opened the program, and he was brilliant. Addressing a multiracial audience, he said, “The first man in this country to die in the war for independence was a black man named Crispus Attucks! A black man!” The audience applauded. Stokely paused, then stunned the audience: “He was a fool! A fool. He got out there and got shot for white folks while his brothers were enslaved all over this country. He should have gotten his brothers together to take care of natural business.” In light of the upcoming fourth anniversary of the March on Washington, the documentary broadcast vivid scenes that evoked the recent past’s expansive hopefulness. Black Power, according to narrator Sander Vanocur, provided evidence that dreams imagined four short years ago had been displaced by the anger of urban militants.51

Stokely was incarcerated in Autauga County Jail in the small city of Prattville. By the next day, the presence of over one hundred national guardsmen from Montgomery and Alabama state troopers left Prattville in a virtual state of martial law. In Chicago, hearing of Carmichael’s arrest, activists threatened new types of “racial upheaval” if he was injured. Rumors spread that authorities had snatched Stokely from jail to be lynched. While Stokely was in jail, white vigilantes fired into a home where black militants, including SNCC activists, had converged to plot a response to Carmichael’s arrest. Police cordoned off a twenty-block area of Prattville’s black community searching for people who had allegedly fired on officers that same night. State troopers and national guardsmen searched every home in the area rounding up dozens of frightened residents, but found only one double-barreled shotgun, one 22-caliber rifle, and one spent shotgun shell. Ten locals were taken into custody in the early morning of June 12. Carmichael posted bond on Tuesday, June 13, and departed Autauga County Jail, surrounded by National Guard troops. The same day President Johnson nominated Thurgood Marshall to become the nation’s first black Supreme Court Justice.52

Racial violence in Alabama spread to Tampa, Florida, sparked by the police killing of a black teenager. On Wednesday, as Carmichael and Rap Brown drove to SNCC’s Atlanta headquarters, newspapers reported outbreaks of violence in at least half a dozen cities, ranging from sporadic flares in Youngstown, Ohio; Newark, New Jersey; and Watts, to more significant upheavals in Tampa and Cincinnati. Rioting in Cincinnati amplified national anxiety over deteriorating race relations, a situation that Rap Brown’s Thursday night appearance there only exacerbated. Brown’s prediction that Cincinnati would burn until the departure of national guardsmen he described as “honky cops” increased his own political notoriety at a high cost. Brown’s inflammatory polemics cast him alongside Carmichael as one of an infamous duo spreading national racial disorder. Brown’s remarkable ability to offer memorable provocations to newspaper reporters and in speeches would outpace his long-term political effectiveness.53

On Saturday, June 17, Stokely visited Boston’s Roxbury neighborhood. His star-crossed relationship with the nation’s Cradle of Liberty, which helped galvanize support for Edward Brooke, would soon touch the city’s local politics. Boston was in the midst of a mayoral election with no less than twenty-six candidates. They included Boston Schools Committee member Louise Day Hicks, an outspoken advocate of maintaining segregated schools. Boston Schools Committee chairman and mayoral candidate John McDonough warned that Hicks’ potential victory offered “an open invitation to the Stokely Carmichaels” to plot racial strife in a city brimming with ethnic and class conflicts. The mayoral election, which pitted Hicks against the eventual winner of the primary and the general election, thirty-nine-year-old racial moderate Kevin White, offered a prelude to angry controversies over school busing that would grip the nation in the early 1970s.54

Despite Carmichael’s bold words regarding Black Power, it was his antiwar stance that most troubled LBJ. During a July 10th meeting with FBI investigations chief Deke DeLoach, Johnson characterized Carmichael as one of three black political activists who required tight surveillance (the other two were King and CORE’s Floyd McKissick). The meeting followed Johnson’s request to the bureau the previous month to find Carmichael’s sources of funding. He remained unsatisfied with the FBI’s answer that Carmichael’s prodigious speaking schedule supplemented his annual $4,500 income as SNCC chair. DeLoach restated long-standing and uncorroborated charges that King’s personal adviser, Stanley Levison, was a high-level communist. He called obscene Carmichael’s recent demand for an almost $2,000 speaking fee at the University of Wisconsin (he settled for $1,300). Johnson floated the idea that the bureau leak information about Carmichael to friendly journalists. Then the president shifted to a second line of attack in the form of House Un-American Activities Committee hearings for Carmichael and McKissick, an idea waved off by DeLoach as futile, given the committee’s low standing among the public. Johnson concluded the meeting with a hope that Carmichael’s “anti-Vietnam activities” would remain under tight surveillance.55