If FORTITUDE NORTH provided the largest wireless project hitherto undertaken, it also constituted the first attempt, at any rate in the United Kingdom, to organise the controlled agents into a balanced and mutually-supporting team for the attainment of a particular object and to plan their part in an operation just as one did that of the forces engaged. For in order to be able to report to the Germans those things which we wanted them to believe, it was as important for the observer as for the things observed to be in the right place at the right time.

The first task that lay before B1A and the Special Means Staff was therefore to decide which agents were best fitted to tell the enemy about each part of the operation and to see that their movements and the circumstances of their lives were adjusted to meet the calls which were now to be made upon them. It was in February 1944 that the Directors of Intelligence lifted the ban which had until now prevented BRUTUS from being used for deception. He had a good reason for visiting Scotland inasmuch as the majority of the Polish troops were stationed there and he was recognised by the Germans as a highly trained military observer. To BRUTUS, therefore, was given the main responsibility for reporting on Scottish Order of Battle and locations. For Northern Ireland FREAK was chosen. We had no agent with Northern Irish connections, but as FREAK was a military attaché, he seemed as likely as anyone to hear about this part of the FORTITUDE NORTH Order of Battle. PANDORA in Dublin was thought to be too unreliable. On account of his residence in Glasgow, GARBO’s agent Three was to cover the naval exercises in the Clyde, while his sub-agent 3 (3), a seaman, was to be sent to Methil to watch the shipping concentrations there. Several of the lesser agents were to be made use of as the occasion offered.

Before FORTITUDE NORTH was set in motion, we had reason to suppose that the Germans already believed three things. First, that Fourth Army existed, or at any rate had existed in the autumn of 1943, as an offshoot of Scottish Command with its headquarters near Edinburgh. Second, that the 52nd Lowland Division was in the east of Scotland; they had had this both from our controlled agents and from their own Intercept Service. Third, that the 55th United States Division was in Iceland. They had been told this repeatedly by COBWEB and BEETLE.

Two days before the wireless net opened on 24th March, FREAK reported the arrival of the 2nd British Corps at Garter House, near Stirling, from Scotch Corner in Yorkshire.1 A week later GARBO’s agent, Three, said that he had seen in Dundee the 52nd Lowland Division as well as an unidentified formation with the sign of a shell on a dark background. Referring to the latter GARBO commented: ‘This insignia is completely unknown to me.’2 Two days later, on 30th March, FREAK ran into an officer from the American XV Corps in London, who told him that this formation was in Northern Ireland with the 2nd, 5th and 8th Infantry Divisions under command. His informant also mentioned that the 55th British Infantry Division was in Ulster.3 Finally, he added the significant fact that he himself was stationed in Edinburgh and was attached to the staff of General Thorne, the Commander of Fourth Army, the reason being that XV Corps had been put under Fourth Army.4

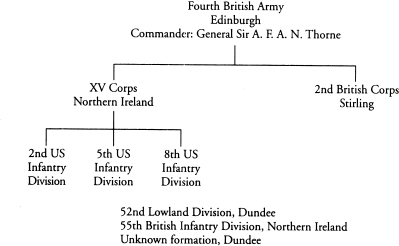

Let us see what the Germans should have discovered by 1st April as a result of these reports. The location of Fourth Army at Edinburgh was confirmed. General Thorne was now its commander. It had under it the American XV Corps in Northern Ireland, which comprised the 2nd, 5th and 8th United States Infantry Divisions. The 2nd British Corps had just moved to Stirling. It was, therefore, not unreasonable to suppose that it might be connected in some way with Fourth Army. The 55th British Infantry Division was in Northern Ireland and a strange insignia had been seen at Dundee. On this fragmentary intelligence the Germans might have been able to reconstruct the following grouping of forces:

The most informative of these reports had been sent by FREAK. It was therefore only right that he should have received the highest commendation from his German masters. ‘Your latest wires very satisfactory. Please continue. Congratulations. Wire as often as possible and watch out carefully in course of next few weeks. Please state exact numbers of divisions, &c., belonging to Fourth Army under General Thorne. Is anything pointing to intended landings in German Bay, Denmark, also Southern Sweden?’5

Let us follow the process a stage further. In a letter which was expected to reach the Germans about 6th April,6 GELATINE told them how she had proposed herself to a friend in North Berwick for Easter, but had been put off on the ground that a ‘Visitors ban’ was about to be imposed in the district. Her correspondent had gone on to say that her husband was working for General Thorne, who ‘had been given command of some new army or other they are forming’. The husband was to have an American for his deputy and was going to ask the General if he could get ‘Bud’. GELATINE then explained, in the covering letter, that her friend in North Berwick was an American married to an Englishman and that ‘Bud’ was her brother and was stationed in Northern Ireland. This confirmed the connection between Fourth Army and XV Corps as well as the presence of American officers at Fourth Army Headquarters.

Early in the month BRUTUS had told the Germans that he would have to visit Scotland shortly for a conference with the Poles.7 Returning to London on 12th April he sent a series of messages which filled in most of the remaining gaps.8 Fourth Army, with its headquarters at Edinburgh (insignia, a rectangle divided into stripes of red, black, red horizontally with a design like the figure 8 in yellow, the bottom part of the lower circle being missing)9 was composed of 2nd British Corps with its headquarters at Stirling (insignia, three wavy blue lines on a white rectangle and a red fish obliquely, the head at the top)10 and 7th Corps, headquarters in the Dundee area (insignia, a sea-shell on a blue rectangle). This explained Agent Three’s observation in Dundee on 28th March. BRUTUS had heard that the Fourth Army also included an American Corps, but he had not been able to identify it. He had found the 58th Division (insignia, a stag’s head full face on a black square) in the district south-east of Stirling, and the Norwegian Brigade at Callander.11 Many of the men of the 58th Division were wearing the Africa Star medal. He had also seen the Lowland Division (insignia, an oblique white cross on a blue shield with black outline) in the Perth–Dundee area and to the North. Finally, he mentioned that a British brigade stationed in the Orkney Islands was said to belong to this Army.

Four days later, on 20th April,12 COBWEB reported from Iceland that he had heard from an American lieutenant that the 55th US Infantry Division was under the command of the 7th Corps, the latter being in Scotland. Thus, by the end of the month, Fourth Army had been confirmed beyond doubt at Edinburgh, with the 2nd and 7th British Corps under command as well as an American corps whose number was unknown to BRUTUS, but which FREAK had already identified as XV Corps. The composition of the 2nd British Corps had not yet been disclosed to the Germans, but they had been told that its headquarters were at Stirling and that the 58th British Infantry Division was in the immediate vicinity. COBWEB had told them that the 55th US Division was under the command of the 7th British Corps and they had learnt from BRUTUS that the 52nd Lowland Division also was near Dundee, where the 7th Corps Headquarters was situated. There was the Norwegian Brigade in Perthshire, and a British brigade in the Orkneys. The April budget of intelligence from the controlled agents might therefore have allowed the Germans to reach the following tentative conclusion:

With that Special Means felt that it had made as large a contribution to the FORTITUDE NORTH Order of Battle as it was safe to do. At the same time it must not be supposed that the controlled agents confined themselves to bare observation of troop movements in Scotland, refraining from any hint of Fourth Army’s operational role, beyond that which the location and training of its formations might imply. These, indeed, could hardly fail to suggest Scandinavia as the objective and the agents did not hesitate to draw the obvious inference. BRUTUS’s Scottish report concludes with a plain statement that an attack on Norway must be expected at the beginning of May.13

Naval developments were being watched at this time by GARBO’s agents 3 and 3 (3) in the Clyde and on the Forth. The former followed with interest the movements of the naval assault forces off Greenock and sent an eye-witness account of the big exercise in Loch Fyne on 10th and 11th May.14 He ended his report by expressing the belief that the manœuvre was a preliminary to an attack and, since the division concerned had been provided with arctic equipment, it was to be presumed that Norway was the objective. 3 (3), who arrived at Methil on 1st April and was to remain there for some six weeks, sent periodical reports on the shipping assembled there. He learned from sailors in the port that an operation was pending, that this concentration was for the transport of supplies and that the troops engaged would embark from other Scottish ports.15 In order to provide corroboration from another quarter, TEAPOT, the triple-cross agent in Hamburg, was asked to send reports about the traffic on the Hamburg–Flensburg line and through the Baltic ports.16

It was to be hoped that the combined effect of the measures already enumerated would be enough to convince the Germans that Norway was the objective and May the target date. But FORTITUDE NORTH had more to tell than that. There were to be two attacks. There was to be Russian co-operation in the North. Diplomatic pressure was to be brought on Sweden in order to secure to us the use of Swedish airfields, and as soon as the Allies were firmly established in Southern Norway, an attack was to be launched against Denmark. Since calculated indiscretions on the wireless were not allowed, only Special Means could enlighten the Germans on these points.

The strongest evidence of an intention to attack in more than one place was provided by Plan PREMIUM. This ruse, which was used to help the threat to the Pas de Calais as well as the Norwegian operation, was entrusted to MULLET and PUPPET. At the beginning of February MULLET announced that he had accepted part-time employment at the Fire Office Committee.17 This Committee has for many years provided a meeting ground for the leading British insurance companies where matters of common interest can be discussed, and has accumulated at its City office copious records about buildings and other insurable effects in all parts of the world. When the war came and communication with foreign and neutral countries practically ceased, these records proved to be of considerable value to the Service departments, a fact which was duly noted by MULLET, who, about a month after his appointment, drew the attention of the Germans to the numerous requests that were being made by ‘Civil Affairs’ Headquarters for inspection of documents in the Committee’s possession.18 He had the ingenuity to see that the places about which they required information might have an operational significance. For the time being, interest appeared to centre chiefly in Northern France and the Low Countries. ‘They are requesting at the present moment urgent information on (1) flour mills, (2) bakeries, (3) cold storage plants, (4) printers.’ Details of the places affected were then given.19 Three days later there came a change of priorities and similar information was now required about Norway. ‘Norway has been divided into two main sectors: one in the South and the second in the Narvik area. MULLET had details about Aalesund, Bergen, Oslo, Larvik, Stavanger, Moss, Skien, Porsgrund, Kristiansand, Trondheim. I believe from the urgency of the requests that something is very definitely afoot in this direction, both because the strictest secrecy is imposed and because only trustworthy members of the Fire Office Committee have been informed about it, these being the people who will handle the work.’20 About a month later MULLET was still working on the bakeries in Norway and, to lend colour to the story, he gave the names of some real bakers, ‘Nordby and Olsen in Oslo, Kristensen in Kristiansand, Moller in Larvik’.21 These names were, of course, extracted from the records of the Fire Office Committee, which we had borrowed. At the end of April MULLET was able to announce that he had finished his work on Norway and was back on Belgium and Northern France.22

The brief which TRICYCLE took with him to Lisbon at the beginning of March allowed him to speak of close Anglo-Russian military co-operation as a possible indication of an impending attack on Norway. But the only positive evidence of such collaboration was provided by BRUTUS on 4th May23 when he stated that, according to his headquarters, a Russian military and naval mission had installed itself in Edinburgh.

It was the responsibility of the London Controlling Officer to bring diplomatic pressure to bear upon Sweden. With that end in view Plan GRAFFHAM24 was devised. In March 1944 we really were making certain demands upon Sweden through diplomatic channels, the chief one being an attempt to prevent them from exporting ball-bearings to Germany. If to those demands which we genuinely wished the Swedes to concede could be added others, genuinely presented with the object of increasing enemy suspicion but to whose concession we did not attach any real importance, the threat to Norway might well be heightened. Accordingly, a number of such additional demands were framed. His Majesty’s Minister, supported by his United States and Soviet colleagues, was to present to the Swedish Government demands for the following facilities:

(1) Right of all civil aircraft to land at Swedish airfields, thus avoiding coming within the range of German fighters.

(2) Permission to send British transport experts to consult with the Swedish experts regarding transport of supplies to Sweden and Norway in the event of a German withdrawal.

(3) Permission for PRU aircraft to operate for survey and reconnaissance purposes over Sweden.

It happened that the Minister was in London during March. This made it possible for the London Controlling Officer to brief him personally. The very fact of his presence here could also be turned to our advantage. Thus TATE reported on 25th March: ‘Mallet, British Ambassador in Stockholm, is in London for special conferences, according to a friend who knows him well. After intensive interviews he is going back there very soon. Said to be taking back extra staff. Friend believes that important negotiations with Sweden are being started.’25 Other high officials and senior officers visited Stockholm shortly afterwards to add an air of reality to the negotiations.

The connection between the attack on Southern Norway and the subsequent capture of Denmark was not an easy thing to suggest to the enemy. It implied a knowledge of future plans which an enemy agent would seldom have the good fortune to acquire. BRONX did her best with the following: ‘Commander, who is at the Admiralty, thinks that the logical place for invasion is Denmark and said that his Rear-Admiral was of the same opinion in spite of the difficulties of air support which would be resolved by the occupation of South Norway.’26

If some of the finer points in the story still remained unresolved, it was felt that this would do us no great harm. Indeed, so long as the German Commander in Norway believed that we were coming soon, lack of precise information as to where the attack was to be made would tend to make him stretch his forces, and that, after all, was what we wanted.