As a result of the reversal of policy in the field of visual deception, which has been recorded in the last chapter, the fulfilment of the plan was now destined to rely basically on wireless and the controlled agents. Control of the latter having been reserved by SHAEF, the detailed plan of the Joint Commanders, in so far as it was concerned with a threat to the Pas de Calais, thus became in essence a programme of wireless deception.

As with FORTITUDE NORTH, the Order of Battle was to provide the foundation for the new plan. The Order of Battle for the Pas de Calais operation had exercised the minds of the Deception Staff at COSSAC since the previous summer, but in the early days it was difficult to know how far to go. It was always assumed that the Joint Commanders would be made responsible for detailed planning and it was realised that the sham Order of Battle was bound to depend largely on the real one, whose composition was not yet known. On the other hand, it was felt that both wireless and Special Means should have as long as possible to impress the false Order of Battle on the enemy. For that reason a start was made in September 1943. At that time the only available guide was to be found in the successive drafts of APPENDIX ‘Y’. According to this plan, it will be remembered, the continuation of the threat after D Day was to be a mere diversion carried out by a force of six divisions; for the period antecedent to the invasion day no precise scale of assault was specified in the plan, but it could be assumed that the force would comprise the real invasion armies, together with the six divisions which had to be found for the post-assault phase. In the latter part of 1943, therefore, the deception requirement appeared to be for an army of two corps each containing three divisions, one of these divisions to be an assault division and another a follow-up division. This being so, it was decided to make GHQ, Home Forces, into the imaginary army, and on 19th September it was connected by two wireless links to 21 Army Group.1

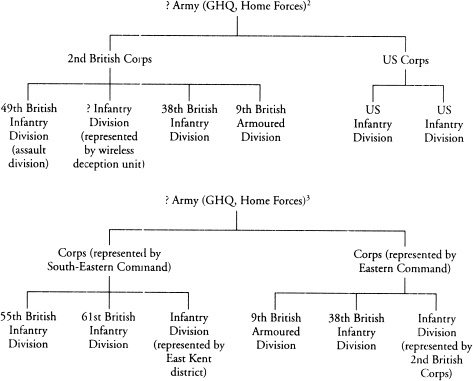

During the ensuing months there were two arrangements which alternately seemed to find favour. These are given below:

2. COSSAC/2356/Ops, dated 14th December, 1943.

3. SHAEF/18219/Ops, dated 29th January, 1944.

Both had GHQ, Home Forces, as the Army, but in one case 2nd British Corps and an unspecified United States Corps were to be employed, while in the other case Eastern and South-Eastern Commands were to represent two corps. Under the first arrangement, which was already taking shape in October, the 49th British Infantry Division was to be used in the assault. The reader will remember this as being the reason for the recruitment of GARBO’s contact 3 (2), who was reported to have said, in October 1943, that the 49th Division was the best in the country and would ‘form the bridgehead’ when the invasion came.4 By December, however, views had changed, and on the 3rd of that month a wireless network on fixed lines was opened representing the second arrangement shown above.5

A decisive turn was given to deceptive planning, and one which was to have a profound influence on the Order of Battle, by General de Guingand’s letter of 25th January, 1944, in which he proposed that, after the invasion had taken place, the Pas de Calais operation should be represented to the Germans as the main attack. This meant that the small imaginary force of six divisions required by APPENDIX ‘Y’ would be wholly inadequate. In order to provide the necessary increase in the striking force after D Day, SHAEF, on 3rd February, produced an amended false Order of Battle.6 The imaginary army of six divisions under GHQ, Home Forces, was retained, its composition having reverted to arrangement number one, but with the omission of the 49th Division.7 According to this proposal, we now had for the pre-invasion story, the GHQ Army for the assault east of the Dover Straits and for the attack west of the Straits, the real OVERLORD formations. The American V Corps and 1st British Corps were specifically earmarked for an assault south of Cap Gris Nez. After D Day, the GHQ Army, continuing its threat to the Channel coast east of the Straits, would ‘operate with four additional assault divisions which will be mounted in the Portsmouth area to assault south of Cap Gris Nez when the German reserves have been committed’. But where were these four extra assault divisions to be found after V Corps and 1st British Corps had landed in Normandy? One could not start building them up before the invasion because until then the story was to be that the two real assault corps would attack south of Cap Gris Nez. Yet one cannot produce four imaginary assault formations, ready to embark at a moment’s notice, by a wave of the hand. The weakness of the proposal of 3rd February, a weakness derived from FORTITUDE itself, lay in the fact that it did not take sufficient account of the story that would have to be told after D Day. Another disadvantage of this arrangement was that it put the imaginary ‘GHQ’ Army, before the invasion date, under 21 Army Group. As 21 Army Group clearly could not control the Normandy assault and a still bigger one against the Pas de Calais, it would have meant detaching this Army from 21 Army Group at the moment when the invasion occurred and placing it under some other command. Such a change would no doubt have been conceivable, but it would scarcely have helped to strengthen the threat at the moment when strength was most needed.

It was at this point that the Joint Commanders became responsible for detailed planning, and it fell to the lot of 21 Army Group to determine finally the constitution of the FORTITUDE SOUTH forces. 21 Army Group made two changes of fundamental importance. First, it decided to have two distinct Army Groups from the start, one for Normandy and the other for the Pas de Calais. Second, it decided to build the Order of Battle wholly from real operational formations, that is to say, it dispensed with imaginary formations as well as with those under the command of Home Forces and under War Office control.

The creation of two independent forces was done in this way. Although all the American formations in the United Kingdom were at this time controlled and administered by ETOUSA, there was already in existence, albeit in skeleton form, an American army group which was destined ultimately to command the American forces in the field, namely, the First United States Army Group.8 All that was required was to convince the Germans that the two army groups were in an equal state of readiness. Admittedly this course might have been held to militate against the policy of postponement, for it tended to show an increase rather than a decrease in the forces operationally available; but, as the reader knows, this policy in face of the difficulties to which it was giving rise, was already being set on one side.

It now became necessary to provide FUSAG with armies of its own. This was done on the one hand by fictitiously detaching the First Canadian Army from 21 Army Group and putting it under the Americans and, on the other, by representing Third United States Army, still in fact under ETOUSA, as being under the command of FUSAG. The next step was to give the FUSAG forces an eastern bias. The Canadians being already located in Kent and Sussex were ideally placed for their role. In order to complete the picture, it would be necessary to move the Third Army, then located in Cheshire, to the eastern counties. This was accordingly proposed, but an examination of the administrative implications showed that such a course would have placed an undue strain upon 21 Army Group’s mounting programme.9 A simple way out of the difficulty was found, however, in the expedient of representing the divisions of Third Army by wireless in East Anglia, at the same time placing the real divisions in the West on wireless silence.10 Having accepted the risks attendant upon a general curtailment of the visual misdirection programme, that is to say, having decided that imaginary divisions need not be physically represented on the ground, this course was clearly justifiable. These arrangements automatically released the non-operational divisions from their role in the cover plan.

At a conference called by 21 Army Group on 30th March the final Order of Battle and location of forces was agreed upon. This Order of Battle provided a firm foundation for the operation, on which the wireless programme and the Special Means plan could now be built.

The Joint Commanders’ Plan,11 which gave the necessary instructions for all aspects of physical deception, and which gave the Special Means staff at SHAEF its marching orders so far as the controlled agents were concerned, did not receive the approval of the Chiefs of Staff until 18th May. Some weeks before that date, however, many of its provisions were already being carried out. At the end of March sites were chosen for the display of dummy landing craft. On 24th April the FUSAG wireless network became active12 and at the same time the controlled agents began to report the move to concentration.

In an introductory paragraph, the Joint Commanders’ Plan of 18th May recited the FORTITUDE story as outlined in the SHAEF plan of 23rd February. The body of the plan was divided into two parts. Part I related to the threat to the Pas de Calais. Part II was purely tactical in its scope and provided for a number of local feints and diversions in direct support of the Normandy landing. Parts I and II were sub-divided into serials to which the code name QUICKSILVER was given. Only the serials contained in Part I, of which there are five, need concern us here. QUICKSILVER I gave a much simplified version of the ‘story’. The modifications which it effected in the SHAEF story will be considered later. QUICKSILVER II contained the wireless programme. QUICKSILVER III made provision for the display of dummy craft. QUICKSILVER IV laid down the bombing programme which was to be carried out against the Pas de Calais in support of FORTITUDE SOUTH. QUICKSILVER V gave instructions for the execution of certain limited measures of visual misdirection at Dover, including tunnelling operations in the cliff, and provided for night lighting at certain places on the Suffolk coast where dummy craft were to be moored.