By the middle of May, the bulk of the reports concerning the move to concentration were in enemy hands. At this stage the Germans had, as it were, been given all the pieces belonging to the puzzle, but not the key which would explain how to fit them together. For the agents who had been posted to observe the recent troop movements, while they were well qualified to identify single formations and even to say what corps some division belonged to, were hardly of high enough standing to learn about the grouping of senior formations or to discover their operational tasks. For this someone with more exalted connections would be needed. In a certain degree GARBO’s friends J (5) at the Ministry for War and 4 (3) at the American headquarters in London had been able to fulfil such a role. On 10th May, for instance, GARBO gave the following account of a conversation he had had with his American sergeant friend: ‘4 (3) said that the Second Front would open as soon as the two Army Groups destined for operation were ready. One of these, the 21 Army Group, is under Montgomery. The other, the First Army Group, is provisionally under the orders of Bradley. The American troops which are expected here will enter the latter Army Group. He assured me that Eisenhower would give a very important task to the American Army Group.’ But we now required a more continuous view of planning at the higher level.1

FREAK, being a military attaché, would have been in a position to supply intelligence of this kind, and he had on 21st April informed the enemy that the Canadians in South-East England were to be grouped with Americans and not with British, and that an American corps would be brought under the Canadian Army,2 but both he and TRICYCLE were now hors de combat. It was therefore decided to give BRUTUS an appointment at the headquarters of FUSAG, the imaginary army group. Here he would be able to weld together into a connected whole, the heterogeneous reports sent in by the ‘ground observers’. In giving controlled agents highly confidential appointments one is always faced with the difficulty of withholding vital secrets which the agents, by virtue of their position, could hardly fail to discover. In order to be in a position to regulate the flow of intelligence reaching BRUTUS.’s ears, it was considered inadvisable to allow him to work at the main headquarters at Wentworth. The story was therefore evolved that a small section had been set up under FUSAG with the object of recruiting Poles who worked in the German-occupied territory which was likely to be overrun in the near future by the American Army Group.3 This section was to be under the command of an American colonel and was to have Polish Army and Air Force officers attached to it. It was to be located at Staines. It would be necessary for the head of the section, accompanied by Polish Military and Air Force officers, to visit FUSAG formations before they went overseas in order to make the necessary arrangements. In such a position BRUTUS would be able, and yet not bound, to discover any kind of operational intelligence. There was a further advantage in placing him at Staines, inasmuch as it would separate him physically from his transmitter which CHOPIN had at Richmond. Thus any necessary delays could be explained by the difficulty which he experienced in maintaining contact with his assistant.

On 18th May BRUTUS announced his new appointment4 and on the 25th reported that the posting was to take effect on the 27th.5 The Germans were delighted. ‘All my congratulations on your post. It is a pity that you will not be able to stay in London.’6 All the anticipated difficulties attaching to such an appointment were experienced by BRUTUS. On 10th June he complained: ‘I have had to ask CHOPIN to come to Staines to collect the news. Difficult to leave this locality to come to London,’7 and on the following day: ‘With regard to FUSAG, it is difficult for me to penetrate the Operations Room because my personal relations are still weak and because security restrictions are very severe and in principle the Allied Liaison officers are kept apart. Nevertheless I am obliged to be there every day and each day I improve my relations.’8 In spite of all these difficulties, he had, within a week of his arrival, begun the transmission of a series of messages which was to disclose to the enemy by the day of the invasion the entire chain of command of the shadow army group in South-East England.

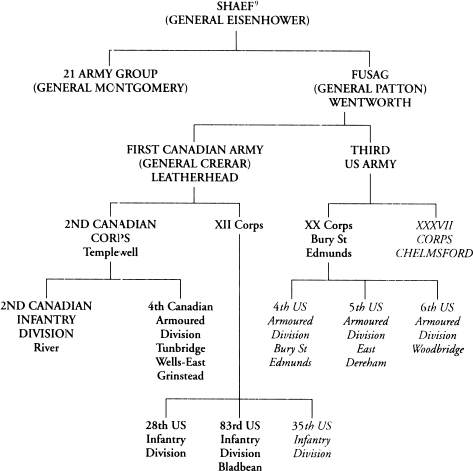

At the end of May, all the FUSAG formations, with the exception of the 80th US Infantry Division and the 7th US Armoured Division, which were in fact only just disembarking in this country, had been discovered by the controlled agents in East and South-East England. The method by which BRUTUS drew all the loose threads together can best be explained diagrammatically. This extensive report was supplied in three instalments; the first from information gleaned at FUSAG, the second after a tour of Kent and the third after a visit to East Anglia.

If one compares this chart with the FUSAG Order of Battle laid down by 21 Army Group on 30th March, one will notice that two of the formations belonging to the First Canadian Army, namely, VIII Corps and the 79th US Infantry Division, have vanished, their places being taken by XII Corps and the 35th US Infantry Division, which were shown under the Third US Army in the original arrangement. A short time before the invasion, it was found necessary to advance the sailing dates of VIII Corps and the 79th US Infantry Division and send them to the bridgehead about a week after the first landing. This, of course, made it necessary to withdraw them immediately from the FUSAG Order of Battle. The gap in the First Canadian Army was filled by transferring the two formations referred to above from the Third Army. This in its turn left a gap in Third Army. The means employed for making good this loss will be considered in a later chapter.10

9. Formations and groupings in large black type reported 31st May, 1944 (1605, 2051, 2056, 2108, 2112 and 2117 GMT), from information acquired at FUSAG.

Formations and groupings in small black type reported 2nd June, 1944 (2003, 2007, 210L 2105 and 2111 GMT), after Kentish tour.

Formations and groupings in small italic type reported 6th and 7th June, 1944 (2005 and 2009 GMT 6th June, 1601, 1604 and 1609 GMT 7th June), after East Anglian tour.

Formations and groupings in large italic type reported 14th June, 1944 (2006 GMT), from information acquired at FUSAG.

As the Germans were learning so much more about FUSAG than they were about 21 Army Group, it is not unnatural that they should have pressed their agents for further information regarding the latter. On 18th May FREAK was asked: ‘Where do you locate 21 Army Group? Which armies and divisions belong to it?’11 At the same time GARBO was addressed thus: ‘With reference to the latest reports of 4 (3), I send the following questionnaire, the reply to which would be of much interest. Where is the headquarters of the 21 Army Group, English? The numbering of the armies within the said Army Group, and their headquarters. How many and which divisions are within each of the armies of the said Army Group, indicating, where possible, which divisions are armoured and which are infantry.’12 On 4th June, while BRUTUS was making the final disclosures regarding the FUSAG Order of Battle, the answer came back: ‘Give details of the composition of the 21 Army Group and of the location of the various headquarters.’13 We had placed ourselves in a fairly strong position to meet questions of this kind. As a foreign liaison officer attached to the staff of FUSAG, BRUTUS could hardly be expected to know very much about the other army group. GARBO’s best source of information where matters affecting military organisation were concerned was an American. ‘I questioned him’, said GARBO on 27th May, referring to a conversation with 4 (3) on the 21 Army Group, but it seems that he does not know much about this formation. He was only able to say that there are a few American troops in it, but that the Americans are mainly in the First Army Group.’14 Such information as we deemed it necessary to give about 21 Army Group in order to match the intelligence which we supposed was being supplied by their ‘Y’ Service, we put into the mouths of ground observers like 7 (2) and 7 (4). There was no need for them to give grouping,15 also, as most of them worked in the Eastern and South-Eastern counties, such reports as they made placed emphasis where it was most needed.