In writing a history of this kind, it is hard to choose the right moment to lift the curtain and let the reader into the enemy’s thoughts. If one does so too soon, one tends, by revealing much that was hidden from us at the time, to obscure and overlay the true causes of contemporary action. If on the other hand one waits too long, one makes it very difficult for the reader of a story of such length and complexity to relate each allied action to its corresponding enemy reaction.

The somewhat arbitrary course has therefore been taken of selecting the invasion as the most suitable date for a full disclosure. On the one hand the bulk of the planning now lay behind us; on the other the fulfilment of our plans was already giving us an insight into the working of the German mind. From this point therefore it becomes possible, without the fear of serious historical distortion, to follow the story from both sides. Henceforward we will carry the Germans with us.

Before going any further we must look back and try to assess the results of our efforts during the previous six months. Let us take the plans in chronological order. BODYGUARD had made SHAEF responsible for telling the Germans that we were ready to reoccupy any part of Western Europe in the event of an enemy withdrawal, that the cross-Channel assault would not be undertaken until the late summer and that we intended to attack Norway in the spring.

No evidence of a reaction to the ‘occupation’ story has come to light. This is hardly surprising, for, as GARBO observed at the time, the enemy would naturally assume that arrangements must exist for entering any part of the Continent which the enemy vacated. Hence there would be little purpose in alluding to such plans in any contemporary German appreciation.

The story of postponement in all its guises found its way to the enemy through practically every Special Means channel. Diplomatic circles in Stockholm, Berne and Lisbon, as well as Abwehr agents, are quoted. The effect of these numerous reports was by no means what had been hoped for. Contrary to our belief, the Germans imagined that a cross-Channel invasion in the winter or early spring was perfectly possible. At the same time the uncontrolled agents, afraid of appearing to have been caught unawares, found safety by prophesying imminent invasion continuously from the New Year onwards. Having become convinced, as early as February, that our preparations were already far advanced, the suggestion of a greatly postponed invasion did not ring true to the Germans. ‘Occasional statements’, says OKH Intelligence Summary of 24th February, ‘from various sources about current reorganisation, and the strong emphasis on “safety first” (especially by Montgomery) encourage the idea of a (perhaps only trifling) postponement…. However, the greatest caution must be exercised when reflecting on this consideration, since enemy diplomatic sources seem to be systematically spreading information about the postponement of the invasion.’1 Some three weeks later a telegram2 from the German Embassy in Lisbon informed Berlin that ‘Portuguese and Spaniards coming from London confirm the view, which prevails there, that England will not undertake any large-scale invasion, but will continue to try by means of air attacks and possibly small landings to tie down Germans in the West, to weaken the German arms industry and in this manner to support the military successes of Russia.’ Berlin’s evaluation can scarcely be said to have advanced the interests of Allied strategic deception. ‘Numerous reports of an alleged postponement of the invasion or of its complete abandonment in favour of an intensification of the air war or of smaller local landing operations are, in the opinion of this Abteilung, to be regarded as systematic concealment of the actual plan.’3

As has been explained in a previous chapter, no attempt, apart from FOYNES, the plan to conceal the divisions returning from the Mediterranean, was made during the earlier phase of FORTITUDE, before the Joint Commanders’ Plan came into operation, to vary the numerical strength of Allied forces in this country. Had we attempted during the spring of 1944 to reduce that strength as was recommended in BODYGUARD, it is unlikely that we should have made any significant impression, for there is conclusive evidence to show that at the end of 1943 the Germans exaggerated our strength by about 50 per cent, a miscalculation which persisted until the end of the war. As the real total increased, so the German estimate rose in like proportion.

As to FOYNES, the Germans, before the end of 1943, were already beginning to notice that these eight divisions had disappeared from the Italian front. That they might have returned to the United Kingdom occurred not only to the Germans but also to the uncontrolled agents as the most likely explanation. The latter, therefore, having been asked by the Germans to locate the missing divisions, thought England as good a guess as any other, and so we read: ‘Independent reports about the transfer of parts of the Eighth British Army from the Mediterranean to England continue. The possibility must, therefore, be considered that individual formations which have not appeared in Italy or North Africa for some considerable time have been transferred wholly or in part to the British Isles.’4 These suspicions were confirmed by occasional disclosures arising from the interrogation of prisoners-of-war and from captured mail. In February a letter from a British soldier stationed in the United Kingdom, which fell into German hands, told them that ‘the Scottish division which came from Italy will presumably take part in the great events due to take place’.5 The enemy had no difficulty in elucidating the fact that the writer intended to imply that the 51st Highland Division had returned to England and was to take part in the invasion.

In spite of these and other indications of a more general nature such as the transfer of landing craft from the Mediterranean to England,6 the Germans tended to regard the evidence as inconclusive and preferred to hold the FOYNES divisions in the base area of the armies on the Italian front, that is to say in Central or Southern Italy, or even in North Africa. On 7th March, the transfer of the 7th British Armoured Division to England was held to be probable, ‘but the inadequacy of available data compels us to await confirmations’.7

With one minor exception, the controlled agents made no reference to any of the FOYNES divisions until the second half of April.8 The 51st Highland Division was the first to be released.9 This was followed by the 9th US Infantry Division and the 50th British Infantry Division at the beginning of May.10 During May these three divisions were constantly alluded to in the controlled traffic and their presence in the United Kingdom accepted by the Germans without reserve. One brief mention was made of the 2nd US Armoured Division on 17th May.11 The remaining three divisions12 were not referred to at all by the controlled agents before the invasion and continued to be shown as ‘unlocated’ in the German records.

To sum up, it would appear that, although the Germans suspected the return of these divisions from the New Year onwards, they did not accept any movement as an accomplished fact until it had been notified by one of the controlled agents. It is of interest to note that whereas the United States formations were allowed normal signals facilities from February onwards, while the British formations remained on wireless silence13 until D Day, no significant leakage through intercept is reported in the OKH Intelligence Summary either from the British or from the Americans. It is true that the German Intelligence Summary for 15th January alludes to ‘suggestions from a sure source that parts of the 82nd Airborne Division have been transferred to England’,14 but that was a month before the division had been allowed to resume normal wireless activity. Moreover the Intelligence Summary remarks a fortnight later: ‘The suspected transfer of parts of the 82nd American Airborne Division does not seem to be substantiated. The bulk of the division must henceforward to assumed to be in Italy.’15

*

Let us now examine the effect of FORTITUDE NORTH upon the enemy. TINDALL the threat which had been made against Norway in 1943 as part of COCKADE, came to an end in November of that year. The uncontrolled agents continued unceasingly to speak of large assemblies of shipping in the Scottish ports. The Germans, however, were more inclined to fall in with a view, more than once expressed by GARBO, that an attack across the North Sea during the winter was highly improbable. ‘Norway has fallen more and more into the background during the last months.’16 The forebodings of the alarmists continued, but the Germans refused to be stampeded. ‘Reports of the movement of shipping into the harbours of Eastern Scotland may show preparedness for a later move down to the invasion ports in South-East England. On the other hand this measure cannot be taken as pointing to the planning of large-scale operations from Scotland, since the present distribution of forces does not offer the necessary conditions for this.’17 There is evidence to show that these uncontrolled reports were doing us some harm at this time. ‘As regards the alleged enemy troop movements and preparation of shipping in Scotland, the impression is growing stronger that such information is consciously intended to direct German attention to this region. An operation of limited scope from Scotland does not seem out of the question, but forces are inadequate for a large-scale operation from this sea.’18

FORTITUDE NORTH came into operation during the third week of March 1944. Only a short time before the enemy had made a fairly detailed appreciation of Norway as a likely Allied objective. This is worth quoting because it shows the German frame of mind just before Allied deception was brought into play.

Reports from otherwise proven Abwehr sources about enemy troop movements and shipping preparations in the Scotland area amount to the following:

The available information consists exclusively of news at third or fourth hand. It in no way provides, therefore, a sure foundation. Other reconnaissance means have lately failed to produce further data from the Scottish area…. We must reckon with four to six active divisions in this area. The shipping reported in East Scottish waters corresponds approximately to the tonnage which would be necessary to transport this force. Troops and shipping available to the enemy command would therefore allow the latter to embark forces in Scotland to a strength of four to five divisions. One or two American divisions from Iceland might be added to this number.

It is thus abundantly clear that if the enemy carries out an undertaking from Scottish ports this will not be a large-scale operation which will seek to be decisive. (Keine entschei-dungssuchende Operation grossen Ausmasses.)

The Norwegian coast might be the target of this undertaking. This Abteilung holds that it would be absolutely improbable for Russian agreement to be obtained to a Petsamo–Murmansk undertaking…. An operation by part of the enemy’s forces against Jutland is only to be expected immediately prior to the great all-out attack against France, as otherwise the Anglo-Saxon forces on Jutland would run the risk of annihilation by free German reserves. Since the course of the weather and certain other factors in the Channel area point away from the imminence of a large landing, the Jutland undertaking seems scarcely likely and Norway the most conceivable target.

Since the operations of the enemy command in the present stage of the war all mean the tying up of German forces on subsidiary fronts, or alternatively their removal from the decisive Atlantic front to subsidiary fronts, and as the enemy has already been successful in this sense in Italy, it seems thoroughly possible that he has come to a like decision in the Scandinavian area. The hitherto inadequate data do not allow us to call this certain or even probable.

It seems nevertheless that henceforward enhanced preparedness on the Norwegian coast and above all an intensification of air reconnaissance over the whole of the North Sea area are indispensable. This measure appears to constitute the only means, which has any prospect of success, of avoiding surprises such as those of the Sicily and Nettuno landings. The pressing home of port reconnaissance in the North Scottish area and the employment of naval forces (U-boats) with exclusively reconnaissance and observation tasks in the direction of Scotland must be regarded as an important additional measure.19

BODYGUARD had miscalculated in two particulars. First in the German appraisement of inter-Allied relations. The enemy saw us as rivals, rather than as partners, in the extreme north. Second in the German belief that Denmark could be attacked without the previous conquest of Norway. This, however, did not materially affect the issue. Taken as a whole, the threat was well aimed. The Germans were predisposed to believe in an attack on Scandinavia ‘to tie down forces on subsidiary fronts’, and already, without assistance from us they thought that four or five British divisions with shipping to transport them might be available in Scotland, to which might be added one or two American divisions in Iceland. It will thus be seen that FORTITUDE NORTH began its career under favourable auspices.

The confession that all sources of intelligence other than Abwehr agents had failed to produce information from Scotland and that the latter had only been able to give third-or fourth-hand reports shows that we owed our flying start chiefly to German preconceptions, but partly also to the uncontrolled agents, even if the latter had on occasion somewhat overplayed their hand.

An appreciation of 3rd April gives us the German view after FORTITUDE NORTH had been in operation for a little over a week. ‘Information about the concentration and preparedness for invasion of the Scottish group of forces in the region of Edinburgh continue. Their strength is still to be regarded as five to seven divisions.20 There is no concrete evidence as to their target. It therefore remains undetermined whether reports about their proposed employment against Norway or Denmark are correct. The essential fact remains that in either case theirs could only be a diversionary undertaking.’21 It is not possible to deduce from that brief statement how much was due to FORTITUDE NORTH. Things, however, seemed to be moving in the right direction.

With the arrival of BRUTUS’s series of messages22 which were sent between 13th and 16th April after his fictitious visit to Scotland, one is left in no doubt as to whether FORTITUDE NORTH had struck its mark. ‘An Abwehr source, which has hitherto reported accurately, has been able to provide a clarification of the distribution of forces in Scotland.’23 Although no attempt at grouping was made, nearly all the elements of which the force was composed were now accepted by the enemy, those at least to which Scottish locations had been given. The 2nd and the 7th British Corps were included, also the 52nd Highland Division and the 58th British Infantry Division. ‘The 7th English Army Corps’, says the German Intelligence report, ‘whose location was hitherto unknown, is in the Dundee area.’24 We had only just invented the 7th British Corps and this was the first time that we had told the Germans about it, but they never liked to admit that any item of military intelligence was entirely new to them. It will be remembered that when christening the 58th British Infantry Division we chose that number because we knew from Most Secret Sources that the Germans believed such a formation to be located in the area of Windsor. It was therefore gratifying to read: ‘In the same area (i.e. between Edinburgh and Stirling) is the 58th English Infantry Division which was hitherto assumed to be West of London in the Southern Command. Since there has, for a considerable time, been no confirmation of the presence of the division in the latter area, its transfer to Scottish Command at the beginning of this year must be presumed.’25 Unaccountably the 50th British Infantry Division was also included and was located between Edinburgh and Stirling.

It will thus be seen that on the British side the FORTITUDE NORTH Order of Battle, thanks mainly to BRUTUS, had been accepted almost in its entirety. The American part of it, however, had not gone so well. The reader may recall that the main report on XV Corps and its three divisions had been sent by FREAK on 30th March. The fact that he had been congratulated on his message made us assume that it too had borne fruit. By some mischance, however, it evidently went astray with the result that BRUTUS’s veiled and confirmatory reference to the fact that the Fourth Army also included an American army corps ‘not identified by him’ became linked in the German mind with an uncontrolled report of American forces in North-Eastern Scotland. Thus we find in the appendix which analyses BRUTUS’s Scottish report the statement: ‘In addition American troops it unknown strength were reported, and these are probably the American Infantry Division of unknown number, assumed to be in the county of Aberdeen.’

BRUTUS’s reports must have been greatly welcomed by the German Intelligence Staff. If one looks at the Fremde Heere West map of 31st December, 1943, one will find no fewer than three British infantry divisions in Scotland without number. These numbers could now be provided, so long as one insisted that there had been no substantial increase in the total of forces located in the North. Hence their statement that from BRUTUS’s report there ‘emerges the fact that the total number of Anglo-American formations hitherto believed by this department to be in that area has increased by one division. As the source in question has supplied a comprehensive explanation, the presence of additional formations is held to be unlikely.’ Hence also the entirely unwarranted assertion that ‘since these changes go back to the beginning of the year, our erstwhile appreciation of enemy intentions from this area remains unaffected’.26

In spite of the efforts of COBWEB,27 we never succeeded in persuading the Germans of the presence of the 55th US Division in Iceland. By the beginning of May they had accepted it as part of the Northern force, but they preferred to locate it in Scotland.28

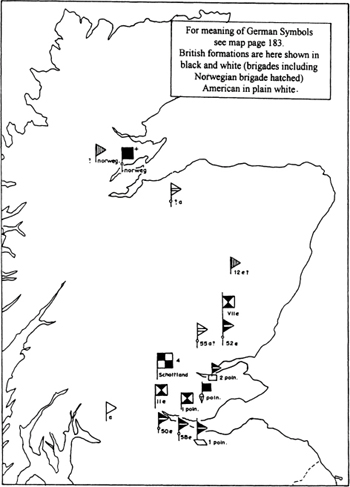

The accompanying map, published by the General Staff Fremde Heere West on 15th May, 1944, provides the best measure available of the success achieved by FORTITUDE NORTH, at least so far as Order of Battle is concerned. In Scotland the position shown leaves little to be desired. Northern Ireland, on the other hand, largely, no doubt, as a result of the failure of FREAKA’s message, is held to contain nothing more than an American brigade of unknown number and a miscellaneous collection of low-grade American troops with a total strength of about twenty thousand.

Location of formations engaged by FORTITUDE NORTH given on the Fremde Heere West map of 15th May, 1944 (Northern Ireland omitted).

Of the ancillary measures taken to support FORTITUDE NORTH, pride of place must be given to GRAFFHAM. That the story reached its mark is proved by the report of a leakage from the British Embassy it Stockholm. This leakage was, of course, intentional and the ambassador’s remarks were designed for German ears. ‘From a reliable diplomatic course (Stockholm) 11th April, 1944: The English Ambassador, Mallet, who was in England for some time, gave on his return a talk to the Embassy staff which, according to an agent’s statement, contained the following passage … We have always had good relations with our Swedish friends and hope that these will remain so. We must, however, reckon with the possibility that this good relationship will be put to the test. We can no longer calmly look on while neutral countries deliver goods to our enemies, which do us harm. We will therefore make representations to the Swedish Government to stop these deliveries or at least to reduce them. We must approach this delicate task with tact. In particular, deliveries of iron ore and ball-bearings benefit Germany and harm us. That must not continue in the future. We must find suitable ways to prevent it. Other problems, too, are of greater significance politically and may come between us and Sweden.’29

That GRAFFHAM not only reached the most influential quarters but caused a favourable reaction is shown by the following quotation from the OKH Intelligence Summary: ‘Reliably reported soundings by high-ranking English Air Force officers in Sweden which aimed at the handing over of Swedish air bases for invasion purposes, may be regarded as an indication of the planning of a small operation in the Scandinavian area (Sweden, Norway and Denmark). The employment of a stronger group of forces in this direction with an operational target is still held to be unlikely.’30

No evidence has so far been found to show that wireless deception or visual misdirection made any contribution to FORTITUDE NORTH. On the contrary, so far as the latter is concerned, the OKH Intelligence Summary complains on more than one occasion about the lack of air reconnaissance over Scotland. Solitary flights are recorded from time to time, but as the Germans themselves admitted, ‘these single results do not give a clear picture of the shipping situation in Northern English ports’.31

Inasmuch as FORTITUDE NORTH aimed at convincing the Germans that certain forces were located in Scotland for a certain purpose when in fact those forces either were not there at all or at least were not there for the purpose stated, the plan, through the operation of Special Means, will be seen to have succeeded. The Germans accepted the danger of a diversionary attack against Scandinavia. They also accepted the presence of most of the formations which we had created or appropriated for the purpose of exercising that threat. To what extent did FORTITUDE NORTH succeed in tying down additional forces in Norway and Denmark? We have it from Jodl32 that Hitler had always been obsessed by the fear of an Allied attack on Scandinavia. It would not have required more than 100,000 troops to garrison the two countries and keep the native population in subjection. In fact the average number of occupational troops had been in the region of 250,000 even since Norway was first occupied. The balance of 150,000 was to be regarded as an insurance against invasion. In these circumstances any minor troop movement that may have occurred in the spring of 1944 (and it is true that the garrison was increased at that time by one formation, the 89th Infantry Division) loses its significance, and one is thus forced to the conclusion, if one accept’s Jodl’s view, that FORTITUDE NORTH, though successful as a deceptive operation, had no influence upon the course of the war. It was, in fact, a case of the fly on the axle-tree.