Before attempting to trace the influence of FORTITUDE SOUTH upon the Germans it will be well to acquaint ourselves with the enemy’s views before the deception plan was set in motion.

The interrogation of those who held positions of responsibility under Hitler has made it clear that the choice of the Pas de Calais as the cover objective was well placed. Long before deception began to exert its influence, the enemy had reached the conclusion that an analysis of relevant military factors weighted the scales in favour of an attack across the Straits of Dover. General Blumentritt has lately expressed the view that a successful landing there followed by a rapid advance into Germany would have cut off all their forces in France, and has stated that this is what they thought would be attempted. That the Fuehrer himself shared the opinion of his experts is shown by an order which he issued in November 1943: ‘I can no longer be responsible for further weakening of the West in favour of the other theatres. I have, therefore decided to strengthen its defences, especially in the place from where we shall begin the long-range fight against England. For there the enemy must and will attack, and there will – unless everything deceives – the decisive landing blow be struck.’1 The ‘long-range fight’ refers to the V weapons which were to come into operation during the following summer. As these were chiefly concentrated to the north of the Seine, it is fair to suppose that this is the area to which Hitler was referring.

At the beginning of 1944 the Germans seem to have held no positive views about the date of the invasion. As has been explained they were constantly being alerted by the uncontrolled agents. Nor had they realised how impossible a winter landing would be. At the middle of January 1944 they thought that the ‘expected attack in the West’ might come in about a month’s time, adding, ‘experience shows that a sufficiently long fine weather period suitable for landing operations may be expected at this time’.2 Three weeks later we read: ‘To sum up, the continuation of invasion preparations of every kind is to be seen, which, according to present opinion, points for the first time to the second half of February as a critical period.’3 These constant alarms continued with hardly a break until, at the beginning of April, the German Intelligence found itself compelled to state: ‘There is a complete absence of information, apart from worthless gossip, regarding the date of the assault. The only protection against surprise is, therefore, to be found in intensively organised sea reconnaissance by air and naval forces (for example U-boats).’4 While soon afterwards the C in C West was to complain of the abundance of new dates for the invasion, ‘some of which are already past’.

As already stated, the Germans greatly over-estimated Allied forces in the United Kingdom at the New Year. They gave us fifty-five divisions when we had in fact only thirty-seven. Let us examine their beliefs in somewhat greater detail.5 Unaccountably, GHQ, Home Forces, remained at Leicester.6 Armies were identified with Commands, which, of course, were known to the Germans before the war. Thus Northern Command was also described as Third Army, Eastern Command as Sixth Army, a legacy from COCKADE, South-Eastern Command, described as Fifth Army, was divided in two to make room for the First Canadian Army at Leatherhead, the boundary running through London, Tunbridge Wells and Hastings, with the Canadians to the West and the British to the East; Southern Command was also designated Second Army. With the exception of Sixth Army, it is impossible to say where the Germans got these British Army numbers from. Scottish Command was shown as an Army Headquarters, but the number ‘Four’ does not appear on the Fremde Heere West map of 31st December. It must, therefore, be assumed that, in spite of what had been done during the previous year, Fourth Army was not yet firmly established in the German mind. At this date no American Army was shown. Of the fifty-five divisions believed to be in the country, twenty-two were correctly named and of these, ten were correctly located. The balance was made up of real divisions in fact abroad, non-existent formations or mere flags on the map without number or designation.7 No particular significance attaches to the German grouping of Allied formations within the Commands. These were spread fairly thinly and fairly evenly along the whole length of the east coast from the North of Scotland to the Thames and more thickly along the south coast from Kent to Devonshire.8 Practically nothing was placed on the west coast, and only two divisions in Northern Ireland. The grouping of formations within these so-called armies seems to have depended upon their location, each army being given all the forces that lay within the Command boundary. Thus a division located in East Anglia would automatically be under the command of the Sixth Army at Luton.

Almost every bay and inlet of the British coastline was shown to contain concentrations of landing craft, the only notable exceptions being the west coast of Scotland, including the Clyde, and Northern Ireland.

At this time and during the ensuing months there was a tendency to speak of three groups of forces, a Northern, a Central and a Southern. The Northern group developed naturally into the Fourth Army of FORTITUDE NORTH, while the Southern group became the FUSAG of latter days. Aided by reports from the uncontrolled agents the Germans sustained their belief in the Central group of forces throughout the spring. It was only under the pressure of the invasion itself and the arguments put forward in support of FORTITUDE SOUTH that they were ultimately willing to admit that it had been dispersed. ‘In view of Abwehr reports of shipping concentrations in the North of Scotland, we must emphasise the possibility that these may be held ready for the group of forces known for some time to be in central England’,9 and again: ‘The troop movements in England have mainly been completed since the assembly areas seem to have been reached. The movements have above all led to the concentration of the central English group of forces, which has hitherto been spread over a wide area compared with the main group in the South of England. It has reached a total strength of some twenty divisions by the addition of one or two American formations. It also includes strong parachute units.’10 Yet another example of this firmly held belief may be given. On 14th April BRUTUS, anxious to dissociate the 1st Polish Armoured Division in Scotland from the Fourth Army, stated that it formed part of the Army Group under General Montgomery. Six days later we read: ‘According to a trustworthy message the 1st Polish Armoured Division is under the command of the group of forces in central England.’11 From this it appears that the Germans had done the central group of forces the honour of giving it Montgomery as its commander.

What has just been said may be described as the geographical solution. Another line of investigation pursued by the Germans, which provided more successful results, was an analysis of the Allied Air Forces. On 15th November, 1943, the Second TAF, which was ultimately to provide the air support for 21 Army Group, was formed from units of Fighter Command and came under AEAF. On 19th December following, the Ninth TAC, providing the air support for the American army group, was placed under the same command. By some means, which have not been brought to light, the Germans must have learnt something of these arrangements, for on 28th January, 1944, they made the following appreciation: ‘According to Luftwaffe Command/Ic. the British close combat formations are being taken away from the organisation of Fighter Command and organised into two close combat corps. This reorganisation is a further sign that they are reforming in accordance with the organisation tried out in the Mediterranean and accords with credible reports about parallel measures within the American Air Force in England.’12 It may be assumed that the two British close combat corps referred to were the 83rd and 84th Groups. The significance of the Mediterranean parallel is revealed in the ensuing sentence: ‘If existing suppositions are confirmed, we must reckon with the employment of two British and two American close combat corps and, following experience in the Mediterranean, also with two British and two American armies.’ In the meantime they had established by wireless intercept the presence of the First American Army Group and the First American Army in the United Kingdom.13 On 17th January a Reuter message had given General Bradley as commander of the US forces in Europe under General Eisenhower.14

About the middle of March wireless intercept disclosed the presence of another American army, the Ninth, in this country. ‘The support given by a sure source to the presence of the Ninth American Army in England confirms the supposition that for the coming operations two American armies (the First and the Ninth?) will be employed in addition to two British armies. This fits in with the organisation of close support formations. It is possible that General Patton, hitherto commander of the Seventh Army in the Mediterranean, will command one of the American armies.’15

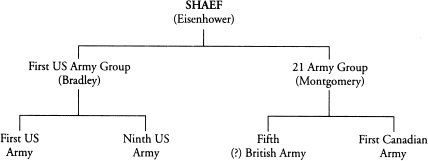

They still could not place the Canadians. ‘It is not yet possible to determine whether they will come under Montgomery’s Army Group or will be employed independently.’16 By 20th April they had found a niche for them, and so the picture was more or less complete. ‘The assembly of two English close combat corps in the sector Southampton–Dover leads to the conclusion that two British armies (the Fifth English?17 and First Canadian) will be launched, while further West we have to reckon with two American armies, the First and the Ninth.’18 With the further information that ‘according to an official English source there is in Great Britain a 21st English Army Group; this is, presumably, the English army group under the command of General Sir Bernard L. Montgomery, of which the number was hitherto unknown’,19 we now have the following arrangement of forces:

This is what the Germans believed the Southern group of armies to be when on 24th April FORTITUDE SOUTH was set in motion.