The brief which was given to TRICYCLE at the end of February before his departure for Lisbon may be taken as the foundation of the FORTITUDE SOUTH Order of Battle. As already stated the main objects of that brief were first, to dispel the clouds which had been raised by the uncontrolled agents and give the Germans a clear-cut picture of our version of the state of Allied forces in this country,1 and second, to fix the positions of certain 21 Army Group formations which we knew would later move to concentration areas not unfavourable to FORTITUDE SOUTH in order that these moves might be noticed and their significance be appreciated. Everyone at the time, TRICYCLE included, felt some doubt about the value which the German General Staff would place on the Lisbon report. In fact that deception far exceeded our hopes. A very full account of it is given in the Intelligence Summary for 9th march, which opens with these words: ‘A V-man message which reached the Abteilung on 7th March, 1944, brought particularly valuable information about the British formations in Great Britain. The reliability of the report could be checked. It contains information about three armies, three army corps and twenty-three divisions, among which the displacement of only one formation must be regarded as questionable. The report confirmed our own overall operational picture.’2 Knowing as one does today that this report filled in a good many gaps on their operational map, the reference to confirmation of the overall operational picture and still more to the doubtful location of one single formation provides an interesting sidelight on German intelligence methods.

This brings us to 24th April, the real starting point for FORTITUDE SOUTH. Let us now focus our attention more directly on the Channel coast and see what the Germans thought about our dispositions in the South. While they never doubted the existence of the ‘southern group of armies’, they changed their minds very frequently as to its main point of concentration. Sometimes it was in the South-West, sometimes in the South-East and sometimes in both. At the end of April the pendulum seemed, from our point of view, to be swinging in the wrong direction. This may have been due to the fact that such limited aerial reconnaissance as they had been able to carry out had shown concentrations of landing craft in the South and South-West. ‘Increased air reconnaissance of the south coast of England has revealed that two Schwerpunkte are showing themselves in this area at the present time, namely in the Portsmouth and the Dartmouth/Saltcombe [sic] areas.’3 As they hardly reconnoitred the coast east of Portsmouth at all, presumably because it was too strongly defended, it will be agreed that this appreciation was misleading to say the least and provides yet another example of that persistent tendency to distort the evidence rather than admit that information on any particular was lacking.

It will be remembered that the first thing which the agents had to do was to discover the FUSAG formations in their old locations before they moved to concentration. This meant showing the Third US Army and its subordinate formations in Cheshire, and XX Corps in Wiltshire with its armoured divisions under command. A message from BRUTUS4 giving XX Corps at Marlborough and the 6th Armoured Division in the northern part of Gloucestershire reached Berlin about nine days later in a somewhat garbled form. ‘According to an unconfirmed Abwehr message the American armoured division hitherto accepted in an unknown location is in the Worcester area. This may possibly be the 6th American Armoured Division.’5 On 26th April FREAK6 gave the Third US Army as being located near Knutsford in Cheshire with the 79th and 83rd Infantry Divisions under command. This resulted in the following rather surprising entry: ‘The two American formations assumed to be in Yorkshire and Norfolk may, according to a good Abwehr message, be the 79th and 83rd American Infantry Divisions. Confirmation of this must be awaited.’7 The connection between FREAK’s message and this passage is beyond dispute. Neither of these divisions had been referred to by the Germans for many months and even then they had never been spoken of together. What clearly happened was this. For reasons best known to themselves the Germans had previously located one American division in Yorkshire and another in Norfolk without giving their numbers. FREAK provided them with the opportunity of filling in the blanks on their map. Such slipshod evaluation robbed the message of all its value from our point of view.

After this halting start, an unbroken spell of good fortune attended our efforts. A glimpse of the 6th Armoured Division by GARBO’s agent 7 (7) at Ipswich8 at the beginning of May caused the enemy to place it on record that: ‘The 6th American Armoured Division, hitherto believed to be in the county of Worcester (see Lagebericht West No. 1255) is, according to an as yet unconfirmed Abwehr message, said to be in the East of England in the Ipswich area.’9 Similarly a report by 7 (2)10 that the 28th US Infantry Division had turned up at Tenterden in Kent and another from 7 (7)10 to say that the same formation had left South Wales find their counterpart in the summary three days later: ‘The 28th American Infantry Division was, according to a further Abwehr message, moved from its previous area round Swansea (South Wales) to the Folkestone area in South-East England.’11 It is not necessary to remind the reader that both these moves were false. In reality the 28th US Infantry Division left Swansea but only moved as far as Chisledon in Wiltshire. The 6th US Infantry Division did not move at all. This information, together with a chance message from BRUTUS,12 in which he reported that while on his way to Torquay he had seen troops of the American VII Corps in Salisbury, led to this somewhat premature appreciation. ‘The advance reported by good sources of the 6th American Armoured Division to Ipswich, of the 28th American Division to Folkestone (south-west of Dover) and of the VII Army Corps into the Torquay area points to the already known main concentration areas and further rounds off the picture of completed concentrations.’13

Day by day the plot now began to unfold itself. The discovery of VIII Corps in Folkestone by 7 (2)14 brought us another step forward. ‘The observation by a useful source of the VIII American Army Corps in South-East England (probably in the Folkestone area) makes it seem probable that in that area there are, in addition to the 28th American Infantry Division already reported there, one or two further American formations hitherto not exactly located. The general picture therefore emerges that besides the strong Anglo-American group of forces in South-West England, we must reckon with the employment of single American divisions from all the remaining jumping-off areas.’15 This passage rather suggests that while the Germans still regarded the South-West as the base for the main attack, they thought that a number of small diversionary operations by single American divisions would be launched from the South-East. During the next forty-eight hours further messages from the controlled agents came to be evaluated. The majority of these related to factual movements of 21 Army Group divisions to the South of England. A message from BRUTUS,16 however, despatched on 9th May, strengthened the American position in the Eastern counties. ‘In East Anglia, in the Bury St Edmunds area (some 50 Km. south-west of Norwich) are situated, according to a well-regarded Abwehr source, the XX Corps as well as the 4th Armoured Division.’17 This intelligence was not without its influence and by 15th May we find that German opinion had moved a little further in the required direction. ‘The main enemy concentration is showing itself ever more clearly to be in the South and South-East of the Island. This is supported by the transfer of two English divisions into the Portsmouth area and the recently observed introduction of American formations into the English group of forces in South-East England (so far observed one corps and one infantry division). The launching of single American infantry divisions from the other invasion areas has also to be reckoned with,’18 A subtle change had occurred since 12th May inasmuch as the South and South-East of the Island were now the main invasion bases. The minor and perhaps diversionary operations by single American infantry divisions were relegated to ‘other invasion areas’, presumably the eastern and western fringes of this main concentration in the South and South-East.

Information, real and false, continued to flow in from the controlled agents for the rest of the month. Each item found its place in the German Intelligence summary after an interval of a few days. The position on 31st May is summarised in the Ueberblick des Britischen Reiches No. 30 issued by Fremde Heere West. It will now be useful to examine the contents of that document.

At this time, while most of the FUSAG formations had been given to the enemy, practically nothing had been said about grouping. This was about to be disclosed by BRUTUS in his series of messages sent between 31st May and 2nd June. It is therefore natural to find that the Germans, although they had accepted all that we had to say about the Allied formations and their locations, were obliged to fall back largely on their old preconceived ideas when it came to grouping. Thus the Commands still provided armies as they had done six months before, the only change here being the finding of a space for the First US Army in the western half of Southern Command.19 The total of divisions in the country was still greatly overestimated. In fact it had now risen to fifty-two, including non-operational formations. The Germans put the figure at seventy-nine.20 Of the FUSAG divisions to which reference has already been made, the 4th and 6th US Armoured Divisions were accepted as being in Eastern Command (Sixth Army), while the 28th and 83rd US Infantry Divisions were put under South-Eastern Command (Fifth Army). The Guards Armoured Division and the 11th Armoured Division, whose move from Yorkshire to Sussex had been reported to them by BRUTUS on 25th and 26th May,21 were placed under the command of First Canadian Army, presumably on geographical grounds. There was, as always, a generous sprinkling of non-existent divisions. FORTITUDE NORTH was rather unfairly weakened by the reported moves of the 3rd and 50th British Infantry Divisions from Scotland to the South. The 3rd British Infantry Division we had for long been at pains to exclude from the FORTITUDE NORTH Order of Battle. As for the 50th British Infantry Division, the Germans had only put it in Scotland by a misreading of BRUTUS’s messages sent during the first half of April. Now, rather than admit to any mistake, they preferred to base their view on the assumption that the division really had gone to Scotland first. The central group of armies, having lost the Guards and the 11th British Armoured Divisions as well as the 15th and 47th British Infantry Divisions, was also sensibly weakened. Referring to the move of the armoured divisions, the Germans said: ‘The group of forces in the centre of England has thereby suffered a fresh weakening, a fact which again allows us to conclude that the forces employed from this area will only be given a limited objective.’22

For information regarding concentrations of landing craft and shipping the Germans appear to have relied almost entirely on aerial reconnaissance. Estimates of shipping capacity were consistently too high. By 25th April they had calculated that between Portsmouth and Falmouth landing craft and shipping space would be enough to lift thirteen and a half landing divisions and even this they regarded as an under-estimate. ‘We must suppose that without doubt a considerable proportion, particularly of landing craft, have remained unobserved, since these are, as we know from experience, well camouflaged and are hidden, withdrawn from sight into the numerous bays and waterways along the south coast. We must therefore reckon with a considerably higher landing tonnage.’23 Air observation, however, was exceedingly scanty. The C in C West’s appreciation for 15th–21st May records that ‘air observation was not carried out during the time covered by the report’. The Ueberblick des Britischen Reiches of 31st May gives a total lift for fifteen and three-quarter divisions.

It has been the aim of the writer to complete the story in every particular up to the day of the invasion before proceeding further. In analysing the German conception of the Allied invasion force it will, however, be more convenient to make an exception and pursue our enquiry as far as the middle of June. This course, which can be undertaken without upsetting the sequence of our narrative as a whole, will enable as to study the effect of BRUTUS’s reports on grouping and so bring the first phase in the development of the false Order of Battle to a proper conclusion.

On 6th June, the day of the invasion, the Germans, as a result of information supplied by BRUTUS, made the following appreciation: ‘According to a reliable Abwehr message of 2nd June, the forces at present in the South of England are organised into two army groups (21 English and First American). It seems from this report that the American First Army Group contains the First Canadian Army (approximately thirteen divisions), known to be in Southern Command, as well as the Third American Army, between the Thames and the Wash (approximately twelve divisions). It is not yet clear whether they are under the command of General Bradley or General Patton. 21 Army Group commanded by General Montgomery seems to contain the formations at present in the South and South-West of England which are probably organised in three armies. All the formations which have so far appeared in the landing areas come from this group of forces which is to the west of the line Brighton/Oxford, while at the same time official English pronouncements confirm Montgomery’s command of the landing troops.’24

Something must be said here about the command of FUSAG. At the end of May growing faith in the staying power of FORTITUDE SOUTH led us to fear that Bradley might be revealed as commander of the American forces in France at a time when the deceptive threat to the Pas de Calais was still holding down divisions in that area. It was therefore decided to substitute General Patton, the latter being at that time in command of Third Army, which was not due to go to France until July. BRUTUS told the Germans that Patton was in command on 31st May.25 As it had been officially announced in January that Bradley was in command of the United States forces in Europe and as it had been stated by GARBO26 on 10th May that he was the commander of the First US Army Group, it is not surprising that the enemy accepted BRUTUS’s statement with reserve. A few days later, however, GARBO was able to resolve this doubt. ‘I attempted to find out from 4 (3) where the headquarters of General Bradley are to be found, but as he is at present under Montgomery’s orders in 21 Army Group, 4 (3) had been unable to say where this headquarters might be. I asked him who, then, was now in charge of FUSAG, to which he replied that it was General Patton who had taken over the command which had temporarily been held by Bradley during the first phase of its formation. In the conversation held, I was able to find out that the headquarters of General Patton, that is to say of FUSAG … is situated near Ascot.’27

A comparison of the Ueberblick des Britischen Reiches for 31st May with the subsequent issue of 15th June reveals some interesting developments. Eastern and South-Eastern Command were now combined under the heading of First American Army Group. Southern Command had become 21 Army Group. FUSAG had achieved the imposing total of twenty-six divisions, exclusive of airborne divisions. With the single exception of the 7th US Armoured Division, whose presence we had not yet disclosed,28 all those formations that we intended them to accept now found a place in the FUSAG Order of Battle, making a total of ten29 divisions. To these must be added four divisions which in reality belonged to 21 Army Group, but which had presumably been included because they had located them in South-Eastern Command,30 six lower establishment divisions, which had been included on similar grounds,31 and six purely imaginary ones,32 some of them being followed by question marks. Our airborne strength was very considerably over-rated. The newly formed fictitious 2nd British Airborne Division, which had been reported by BRUTUS on 7th June as being in the region of Grantham, was given under FUSAG. 21 Army Group was shown to have under its command in the United Kingdom no fewer than three wholly imaginary British airborne divisions, the 3rd, 5th and 7th, while another American formation, the 11th Airborne Division, was also put in England, but in an unknown location. The 1st British Airborne Division, in fact still in England, was believed to be in Normandy.

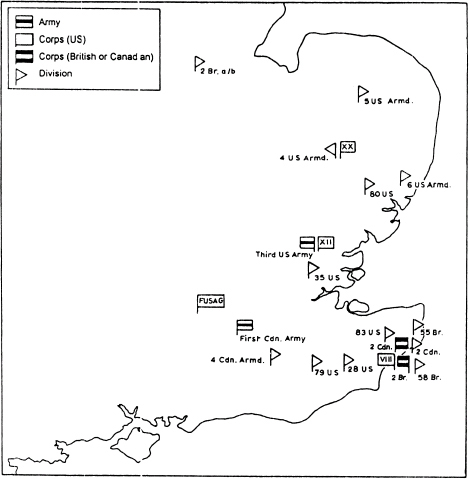

Location of FUSAG formations according to the Joint Commanders’ Plan of 18th May, 1944, with the addition of 2nd British Corps and 55th and 58th British Infantry Divisions, transferred from Scotland at the beginning of June.

Location of FUSAG formations given on the OKH map of 19th June, 1944.

Notes

1. Formations included by the Germans in FUSAG without our authority are omitted.

2. By this date, VIII Corps and 79th US Infantry Division had already been withdrawn from First Canadian Army and had been replaced by XII Corps and the 35th US Infantry Division. This information, however, had only just reached the Germans.

3. Although the 58th British Infantry Division is not shown on this map, it was accepted as being in Kent in the Lagebericht of 24th June, 1944.

4. The 28th US Infantry Division is shown in Suffolk and not in Kent, because we had reported it carrying out assault training at Harwich at the beginning of June.

Having now established the fact that the Germans had, by the middle of June, accepted the entire FUSAG Order of Battle, discarding the more accurate estimate which they had previously formed without our assistance, we may pause for a moment in order to consider more precisely what made them change their opinions.

Wireless intercept had given them one or two useful isolated facts such as the appearance of the First and Ninth US Armies. It had occasionally revealed the presence of a lower formation. It had twice attempted the grouping of formations, but in neither case had it succeeded in giving a wholly accurate report.33 Locations had been attributed to intercept on three occasions only and then only when the location had already been given by a controlled agent.34 Lastly and most significantly from our point of view there had been no single instance of the German intercept service having picked up any one of the deceptive FUSAG nets.35

Let us next examine the claims of air observation. The inadequacy of air reconnaissance was a constant cause of complaint by the German Intelligence Staff. ‘The southern English ports are not able to be checked owing to the present lack of adequate air reconnaissance’,36 and two months later, ‘air reconnaissances during the last weeks covering some of the southern English ports (Falmouth, Cowes, Hamble Esruary) show a considerable increase in landing craft as compared with previous results; nevertheless, the defective reconnaissance results do not permit any deductions to be made as regards the distribution of landing craft’.37 The rather scanty observations of the south coast between Portsmouth and Land’s End that they were able to make during April and May had led them to the conclusion that we had nearly twice as many landing craft as was in fact the case. Overland reconnaissance had nothing placed to its credit at all.

Finally, there was the Abwehr. No matter how much the German General Staff despised the Abwehr as an organisation, they had, owing to the failure of intercept and air reconnaissance, little else to guide them, and were compelled in consequence to base their appreciations on Abwehr reports. Moreover, as the Germans had no effective spy system in the United Kingdom, these reports were supplied exclusively by the British-controlled agents in the United Kingdom and by the uncontrolled agents abroad. The latter, who held the field until the month of April, being denied all knowledge of the Allies’ true intentions, were obliged to content themselves and their masters with evasive and conflicting statements, which kept the enemy in the dark as much as they were themselves. It is therefore not surprising to find that the British-controlled agents, as soon as they had a positive story to tell, rapidly outstripped the freelances. It will thus be seen that the Allied double-cross team opened their campaign practically without a competitor.

Of the British-controlled agents, it is evident that GARBO, BRUTUS and TRICYCLE enjoyed reputations of a high order throughout the whole period of FORTITUDE deception. This came as a surprise to us. We never doubted GARBO’s position. We knew that BRUTUS had attained something at least approaching GARBO’s stature by midsummer, but we had supposed that he had risen during the spring from comparative obscurity. Although we believed that TRICYCLE and FREAK stood in the front rank until the time of ARTIST’s arrest, we feared that they might both have been discredited by that event.

That BRUTUS enjoyed the full confidence of the Germans at the beginning of the year, before we had been allowed to use him for deception at all, is proved by a contemporary German report which states: ‘He is very well regarded and up till now has produced much accurate information on South-East England (formerly Polish General Staff Officer sent to England by us in 1939).’38 Reasons for believing that TRICYCLE’s reputation had not been compromised by the ARTIST affair have already been given. It is now clear that we could have continued to use him and FREAK for deception during the summer of 1944, but there was no way of telling this at the time.

If we under-estimated BRUTUS and TRICYCLE, we certainly over-estimated the capacity of TATE. We realised that TATE was in rather low water when we started to use him for deception in the spring, but we supposed that a sustained diet of high-grade deceptive intelligence would restore to him his position in the front rank. We could not, as was the case with the other agents, observe his progress through a reading of Most Secret Sources, since his control in Hamburg communicated with RSHA Headquarters by land line only. In fact, by the date of the invasion, not one of the messages which we sent through him had found a place in the OKW Intelligence Summary. TATE, both before and for the few weeks succeeding the invasion, was to be a source of weakness, for we were giving him essential parts of the plan to tell the enemy and they were not being told.

Except for the occasional identification of a formation by TREASURE and a few very doubtful scores by MULLET and PUPPET, information from the other controlled agents appeared to have made no impression at all.

According to the available evidence, therefore, the enemy’s belief in the imaginary FUSAG, upon which the successful prosecution of FORTITUDE SOUTH now depended, resulted solely from the messages of the three British-controlled agents, GARBO, BRUTUS and TRICYCLE, the contribution of the last-named being restricted by the fact that he ceased to be employed for deception some three weeks before the date of the invasion.

The reader will recall that after the arrest of ARTIST, the controlled agents were debarred from making any direct allusion to the false objective and date of assault.39 It must not be supposed, however, that all measures calculated to draw the enemy’s attention to the Pas de Calais or to mislead him as to the date of the attack were suspended in consequence. The Air Force bombing programme with its intense concentration on targets in the north-western departments of France only began in May. Its influence is very apparent in contemporary German appreciations. ‘The concentration of enemy air action against the coastal defences between Dunkirk and Dieppe and on the Seine–Oise bridges as well as the neutralising of the south flank between Rouen and Paris might be held to indicate the North-West of France as the objective.’40

Such measures as were taken during May in respect of the timing of the operation were designed rather to conceal the true date of the attack than to mislead the enemy by suggesting a false one. In that regard, the wireless silence periods had, of course, been in operation since the beginning of the year. Their purport had not been lost on the enemy. ‘The wireless silence which was observed for several hours on 24th January was several times noticed in the Mediterranean in the same form and during periods of large-scale undertakings. The silence presumably serves purposes of training primarily, but is also intended to deceive and to lower German vigilance.’41 Nevertheless the Germans had soon resigned themselves to the view that the observation of wireless traffic would be of little assistance to them in estimating the invasion date. ‘The wireless silences which are noticed from time to time in the various English wireless networks (armed services, railways, &c.) are to be regarded as exercises designed to ensure the smooth working of the wireless silence during the invasion. From these silences we must conclude that the invasion will in all probability not be revealed by the wireless network.’42 After the inception of FORTITUDE SOUTH, our chief concern had been to counteract the effect of FABIUS. The Germans claimed that this exercise had been observed both by wireless intercept and by the Abwehr. The Abwehr reports had been supplied by us and were therefore of little assistance to them. Nor do they appear to have learned anything useful from intercept, except our intention to land at low water, information which might have, but apparently did not, enable them to determine the hour of the assault and to modify their coastal defences to our disadvantage. ‘In the area from the Isle of Wight to approximately Brighton there took place from 4th to 6th May a large landing exercise by all three Services during which the recognition and removal of off-shore obstacles at low water seems to have played on important part.’43 This was confirmed by subsequent observations on 23rd May. ‘A landing exercise on the south coast of England at low water on 23rd May, identified by a sure source, may point to a decision to effect the landing on the ebb tide on account of the danger of German under-water obstacles.’44

It will be remembered that when the invasion drew near a final attempt was made to put the Germans off their guard by impersonating Field-Marshal Montgomery at Gibraltar. The numerous questions as to Montgomery’s whereabouts which were received by controlled agents both in this country and in the Mediterranean showed that COPPERHEAD had caused a considerable stir in the lower levels of the German Intelligence Service. There is no evidence, however, that it reached the ears of those for whom it was intended. A possible explanation may lie in the fact that only a few days before, JOSEPHINE, an uncontrolled agent operating in Stockholm, had played exactly the same game. A signal dated 19th May and headed ‘Staff Talks at Gibraltar’ had reported that Tedder, Leigh-Mallory, Bedell-Smith, Maitland-Wilson and other senior officers of the latter’s staff had met in Gibraltar on 14th and 15th May. ‘According to information emanating from the War Office’, they were supposed to have examined the state of preparedness of the large reserves in North Africa as well as the question of a combined operation against France, while the placing of these formations under Eisenhower had been confirmed. That message was seen by Hitler.’45 Supposing that the Germans had accepted JOSEPHINE’s story at its face value, it would seem extraordinary that Montgomery should not have seized the opportunity of meeting Maitland-Wilson at Gibraltar on 15th May and so have saved himself the trouble of going all the way to North Africa ten days later. In fact the evidence goes to show that they did not believe it for it bears the marginal note: ‘Irrefuehrung?’ (deception) and in Colonel Krummacher’s46 handwriting the arch comment, written in English, ‘Who knows?’ It is therefore likely that any COPPERHEAD reports reaching the OKW at all were rejected before they even reached Krummacher’s table.47