Before proceeding further with our account of Allied deception, it will be convenient once more to look behind the curtain and examine the state of German opinion during the weeks immediately succeeding the invasion. Even before the fateful countermanding order had been issued on the morning of 10th June, the enemy had been impressed by the fact that none of the FUSAG formations had yet appeared in Normandy, and had drawn the desired inference.

‘The fact that not one of the formations still standing by in the South-East and East of England has been identified strengthens the supposition that the strong Anglo-American forces which are still available are being held back for further plans.’1 The enemy Intelligence reckoned the FUSAG forces to be much larger than we had ever suggested. This was due to the fact that they included all formations in Eastern and South-Eastern Command, although many of these, both in fact and in imagination, should have been placed in 21 Army Group. This was to prove both a strength and a weakness to us as will be seen hereafter. For the time being this over-estimate operated wholly in our favour for it gave us an unexpected accretion of strength in the South-East. At the same time the Germans were so firmly convinced of the independence of the two army groups that on the few occasions when a formation which was not included by us in FUSAG, and whose movements we therefore omitted to explain, went to Normandy from the Eastern counties, they themselves found some good reason for avoiding the conclusion that Patton was being made to reinforce Montgomery. ‘The arrival of the 51st English Infantry Division (hitherto believed to be the Cambridge area) in the English Second Army area is not to be regarded as an encroachment on the group of forces in South-Eastern England; it is rather to be assumed that this division was already transferred to the sphere of Montgomery’s army group before the start of the invasion.’2 A few days later: ‘From the appearance of the 49th English Infantry Division and the 9th English Armoured Division in the bridgehead which were last observed in the South-East of England, we cannot conclude yet that an encroachment has been made on the American Army Group, since both these divisions were last observed presumably on the march to the south and have clearly not remained (long) in the last named places.’3 And even at the end of the month: ‘The employment in the Normandy bridgehead of the 76th English Division, hitherto accepted in the area north of Norwich, cannot be regarded as an encroachment on Patton’s formations, since the fact that this division was last identified in that area six weeks ago is not necessarily a proof that it formed part of the American army group.’4

At the middle of June, although the Germans realised that limitation of shipping space might involve staggering the FUSAG attack behind the Normandy invasion, they were nevertheless inclined to regard the operation as imminent. ‘To sum up, despite the absence of any concrete information about the enemy’s actual intentions it can only be said that there is no serious evidence against the early employment of the American Army Group and that our own measures must therefore take this possibility into account.’5 Two days earlier the flying bomb attacks had started and the opinion was evidently expressed in some quarters that this might make the Allies attack sooner in order to capture the sites. The German Intelligence staff, however, took a contrary view. ‘Enemy reports show that the V weapon seems so far to have had considerable moral effects. The present impression is that for the moment a determined and short-term destruction by the English Command of the form of attack is not expected.’6 And two days later: ‘There is still no information regarding the time of the attack. Neither is there any evidence that the German rocket attack is having the effect of advancing the FUSAG attack.’7

The large scale of General Montgomery’s operations in Normandy was daily becoming more apparent to the enemy. ‘The consolidation of the Anglo-Saxon bridgehead area is emphasised by the reported transfer of Montgomery’s headquarters thither and by the construction of usable air strips.’8 One gains the impression that even at the middle of the month the Germans did not exclude the possibility of Montgomery using a part of his reserves for another landing. ‘In spite of the appearance of twenty recognised formations in the bridgehead, Montgomery still disposes of considerable reserves (fifteen to seventeen divisions) which may be assumed to be standing ready in the invasion harbours in the South of England.’9 As more of his forces came to France and his reserves became weakened both in quantity and quality this opinion began to lose favour. Montgomery’s reserve was further weakened by the fact that the Germans had, without encouragement from us, placed some non-existent airborne divisions in the South-West of England and now transferred them to General Patton. ‘Of Montgomery’s Army Group twenty-two to twenty-four divisions have so far been identified in the bridgehead. We must take into consideration the fact that these include almost all the battle-tried divisions from England, and will therefore contain a somewhat higher proportion of soldiers with experience of battle than will the remaining formations. Since moreover we must reckon with the fact that the mass of the airborne divisions accepted in South-Western England will only be used in a new landing operation and so presumably as part of the American Army Group, we can determine that the mass of Montgomery’s Army Group is in action in Normandy and can for certain only fall back on a reserve of ten to twelve formations.’10 Although the belief in subsidiary landing operations by 21 Army Group had decreased and the Channel Isles had already been ruled out, the enemy still seemed to have a lingering fear about Brittany. ‘Mining from the air of the harbours in the Channel Islands, Guernsey and Jersey, shows that the enemy does not contemplate landings against these islands at present. On the other hand observations in the West Brittany area deserve attention. Besides the already reported attack on a German locating apparatus in this area, much shipping movement has been noticed during the last days north of the coastal area Morlaix-Brest as well as increased air reconnaissance. Since also the coastal mining shows considerable forbearance in the Brest area, a sudden stroke again at Brest does not seem to be excluded. This might have as its object, besides the capture of the harbour, after it was known that German troops had withdrawn, the tying up and diverting of forces. On the other hand the employment of the still available army group Patton in this area continues to be regarded as unlikely.’11

So far as General Montgomery’s left flank was concerned, the mere belief in the existence of FUSAG made the Seine into the most likely boundary. On 28th June the Germans were able to find confirmation for this view. ‘In connection with the objective of the American Army Group, further captured documents (map issues) from the English Army Group are noteworthy since it can be seen from them that an operation by Montgomery on the north bank of the Seine does not seem to be intended.’12

As Montgomery’s reserve diminished and with it the probability of a secondary landing by 21 Army Group, so the real operation gained in importance while Cherbourg became more clearly recognised as the immediate objective. ‘The early capture of the port of Cherbourg for disembarking operational reserves from the USA may therefore be likely to assume correspondingly greater importance for the enemy command.’13

As to Patton’s Army Group: ‘The American First Army Group remains in East and South-East England in a strength of approximately twenty-eight divisions available and uncommitted to which must be added three to four airborne divisions in the West of England, so that the total strength of the Army Group corresponds fairly exactly to that of Montgomery.’14 In support of the view that this Army Group was ready to attack at any moment, agent 7 (7)’s report of landing craft in the Harwich–Yarmouth district is quoted as well as a claim by the Luftwaffe Command IC that on 19th June they had identified ‘indications of definite and completed preparations for air landing and parachute operations’.15

It mattered little to us where exactly the Germans expected the second landing, so long as it dissuaded them from sending the Fifteenth Army to Normandy. Anywhere between Dunkirk and Le Havre would serve the purpose equally well. It was never necessary, therefore, for the controlled agents to specify a precise objective.16 Nevertheless the enemy soon formed his own opinions on the subject. As early as 11th June the imaginative Luftwaffe Command IC had expressed the opinion that ‘the concentration and retention of strong Anglo-Saxon close-combat formations speaks against the intention to support a Belgian undertaking. The concentration is regarded as rather directed against the southern Channel coast. If this were correct it would be an important pointer to the intended use of the Eastern Anglo-Saxon group of forces (American First Army Group). Since the Normandy Peninsula is already assumed to be the concentration area for Montgomery’s entire Army Group (approximately thirty to thirty-five divisions) and is the disembarkation area for the strong reserves to be transported to Cherbourg from the USA, another landing sector lying in the vicinity must (in the opinion of the Luftwaffe Command IC Foreign Armies West) be assumed for the American First Army Group. On reflection, the sector between the Somme and the Seine seems to be indicated in the first place, because it corresponds to the Anglo-Saxon Air Force concentration and may be expected to afford the possibility of early co-operation between the two Anglo-Saxon Army Groups, roughly towards the line Paris/St Quentin.’ The more cautious OKH added: ‘It is emphasised that apart from this appreciation by Luftwaffe Command no concrete evidence is available in support of these reflections from captured documents, from a sure source or from the Abwehr.’17 The uncontrolled agents could be guaranteed to provide support for any prophecy that the German Intelligence cared to make. Thus it is not surprising to read in the summary issued two days later: ‘Concrete evidence which would indicate the target of these forces is still lacking. It seems, nevertheless, worthy of attention that the view is held at a headquarters of the Central English Command that the operations which have opened are the preliminary to a later thrust to the east on both sides of the Seine; plans based on the Le Havre area are expressly mentioned.’18 And three days after that: ‘The current reinforcement of the beach-head continues; it must, however, not be forgotten that at present only twenty-five per cent of the divisions available in England have been employed here. Worthy of note is an Abwehr message which, though it arrived after the landing, nevertheless forecast accurately the landing so far carried out, and in which a second landing in the area between the Somme and the Seine is foretold with the final object of launching a thrust in the direction of Paris on both sides of the Seine from the two beach-heads thus formed.’19 At the middle of June therefore Belgium was ruled out and the Seine–Somme sector was regarded as the most likely place for Patton’s attack.

On 24th June further evidence that the Allies intended to attack immediately east of the Seine was adduced. ‘The air reconnaissance tasks given by Montgomery’s Army Group (rivers Toucques and Risles) show that this Army Group may in the foreseeable future be directed eastwards against Paris. The direction of this thrust again points to a corresponding attack by Patton’s Army Group in the Seine–Somme area with a view to affording operational support.’20 By this date BRUTUS had completed his series of messages on the grouping and location of FUSAG forces in Kent and East Anglia. These reports were also advanced in support of an assault west of the Straits of Dover, though the reasoning employed is curious. ‘Recent troop identifications have shown even more clearly the strong concentration of forces in the south-eastern part of England. The forces under First Canadian Army consist mainly of English and Canadian troops, the Third American Army concentrated north-east of London mainly of American formations. The composition of both armies points to their employment in the central Channel area21 inasmuch as the army standing nearer to the Continent is made up of the more highly valued British formations.’22 In other words the mere proximity of troop locations in England to the supposed objective, without any apparent regard for embarkation or landing facilities, seems to have counted as an argument with the enemy. It will be observed that in favouring the Seine–Somme sector as the objective of our second assault no reference was made to the natural features of this coastline which would have placed almost insurmountable difficulties in the way of any attacking force and which had ruled out this stretch of coast from Allied deliberations at an early stage of planning.

So far as the other threats were concerned, the Intelligence Summaries made several references to the possibility of an attack on the south coast of France during June; an appreciation made on the 24th of that month may be regarded as typical. ‘Though the numerical prerequisites for a large-scale landing from North Africa are there, there is no sign of adequate preparations for moving these forces. We are still of the opinion that they are intended to tie down German forces in the South of France and the enemy Command would no doubt not refrain from using them to occupy areas vacated by German troops in the event of the latter being withdrawn from extensive areas of the Southern French coast.’23 No fresh news came from Bordeaux; Norway had receded well into the background. ‘The weak state of the forces in Central England and Scotland speaks now as hitherto against any plans worth mentioning against Jutland or Scandinavia.’24

Such were the opinions of the Germans during the month of June. Let us see how they affected the disposition of their forces. The SHAEF G-2 Intelligence Summary, it will be recalled, had forecast that by 13th June three Panzer and three field infantry divisions would have gone to Normandy from the Fifteenth Army’s zone, two Panzer divisions from South-West France and one Panzer division from the Mediterranean coast. In fact two Panzer divisions only had moved, namely, the 2nd Panzer Division from Amiens and the 17th Panzer Grenadier Division from south of the Loire. The longest forecast made by the G-2 Division before the invasion was for 1st July. It was estimated that by that date a total of ten divisions, three Panzer, three field and four limited employment divisions would have gone to the bridgehead from north of the Seine, that a total of two Panzer and one field division would have been sent from South-West France and from the Mediterranean coast two Panzer divisions and two field divisions.

When the invasion took place there were fifteen infantry divisions in the Seventh Army area, of which seven were field divisions. Of the armoured reserve there were three Panzer divisions between the Seine and the Loire, the 21st Panzer Division south of Caen, the 12th SS Panzer Division at Dreux and the Panzer Lehr Division south of Chartres. A month later there were eighteen25 infantry divisions in the Seventh Army’s zone, many of them mere remnants, of which eleven were field divisions. The armour had increased during the same period from three to nine26 divisions. While the strength of the armour had thus increased, that of the infantry, taking into account the heavy casualties which had been suffered, had most certainly declined.

After the 2nd Panzer Division had gone into the battle the armoured reserve north of the Seine still comprised two divisions, the 116th and 1st SS. These, it will be remembered, had converged towards the Pas de Calais on 10th June. Before the end of the month the 1st SS Panzer Division went to Normandy but was replaced by the arrival from Germany of the 19th Panzer Division in Holland. Of the formations belonging to Fifteenth Army, the 346th Limited Employment Division left Le Havre before 18th June to join the 81st Corps in the bridgehead, while the 16th GAF Division went from Haarlem to join the 86th Corps before 25th June. The strength of the Fifteenth Army was further reduced by the departure of the 19th GAF Division from the neighbourhood of Bruges just after the invasion took place.27 On the other hand, the 245th Limited Employment Division appears to have been withdrawn from the battle zone and sent to Dieppe at the beginning of July, while the Fifteenth Army received five other field divisions from Germany and from other theatres of war as reinforcements.28 Thus whereas immediately before the invasion took place there were nineteen infantry and parachute divisions in Fifteenth Army’s area, of which six were field divisions, on 8th July there were twenty-two, of which eleven were field divisions. Before the invasion there had been three armoured divisions north of the Seine, now there were two. In fact the forces in the Fifteenth Army area were stronger at the beginning of July than they had been at the beginning of June.

By the end of the first week in July the South-West of France had lost, in addition to the 17th SS Panzer Grenadier Division which had crossed the Loire before 10th June, one field division, the 276th, this formation having gone to Normandy before 25th June. The Mediterranean coast lost three field divisions at the beginning of July; the 272nd and the 277th went to the bridgehead, the 271st to Fifteenth Army. On the other hand, the 198th Field Division had arrived at Narbonne during June, and it was shortly to receive the 716th Limited Employment Division from Normandy in place of the 272nd Field Division. Responsibility for the loss of the 2nd SS Panzer Division, which had been stationed at Toulouse and which went to Normandy before 18th June, may be shared between IRONSIDE and VENDETTA.

In order to prove that a deception plan has achieved its purpose, it is not enough to show that it reached the enemy Intelligence and was accepted by them as true. It is also necessary to establish the fact that it influenced the actions of the commander and so changed the course of battle. It would be difficult to avoid the conclusion that the German appreciations and troop movements which have been summarised above were not closely related. Lest any doubt should remain on that score, that doubt can be dispelled by the testimony of Field-Marshal Jodl himself. Speaking at a conference in Berlin on 3rd July about the situation in Northern France, he said: ‘The main enemy force used in the landings in this area was Montgomery’s Army Group. This group now has in England no more than four or five infantry divisions and two armoured divisions. On the other hand, it is obvious that Patton’s Army Group (eighteen infantry divisions, six armoured divisions, five airborne divisions) is being made ready in London and in Southern England for the next landing. It is also evident, from the operational sectors of the two enemy army groups and the state of preparations, and from the fact that it would be difficult for the port of Cherbourg alone to supply two army groups, that the landing area will be the Channel region facing the German Fifteenth Army. We conclude that the enemy will plan operations with both army groups on both sides of the Seine, heading towards Paris. Reports of preparations for large enemy landings on the Mediterranean coast of Southern France appear to be largely deliberate propaganda reports by the enemy. We are prepared for landings in the vicinity of Bordeaux and on the coast of Belgium and the Netherlands, although there is little probability of such landings; it is believed at present there is almost no probability of landings in Denmark and Norway. The defences on the front of the German Fifteenth Army are extremely strong; moreover, our troops are disposed with an equal number of coastal defence divisions and of rear groups (nine or ten divisions) directly behind them. Nearly all of the enemy’s seasoned troops with experience in the African and Italian fighting have been expended in the present landings; there are not more than two divisions acknowledged to be seasoned troops in Patton’s Army Group which is to carry out the next landing. Moreover, since this Army Group intends to land in the face of strong German defences, we have every confidence of defeating them.’29

Disposition of German Forces at 6th June, 1944 (319 Infantry Division in the Channel Islands is omitted)

Location of German armoured divisions on the eve of the invasion

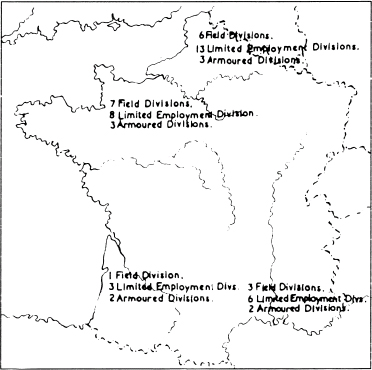

Disposition of German Forces at 8th July, 1944

G-2 Intelligence Forecast of German dispositions at 1st July, 1944, made before the invasion (The total of fifty-seven divisions in France on 6th June is increased to fifty-nine by the anticipated arrival of two infantry divisions from Scandinavia or Denmark.)