By 4th August the Germans appear to have held the view that the danger of a second landing had fallen a little further into the background. ‘Particularly strong landings in the Seine Bay during the past two days (on 2nd August alone seventy-nine freighters of approximately 1.8 million BRT) lead us to suppose that considerable reinforcements have been brought into the Normandy area which will have resulted in a further weakening of the First American Army Group (Southern England) and again makes it seem unlikely that early new landing plans of extensive scope are envisaged.’1

A pointer to which the German Intelligence paid great attention in trying to assess our intentions was the organisation of the higher command. After it had become evident that a second army group was engaged in the bridgehead they were anxious to know who was in charge of the operation as a whole. On 29th July GARBO was asked: ‘Could you find out if the Twelfth US Army Group, recently constituted, is under the supreme command of Montgomery or who is the supreme chief in Normandy of the two army groups which are now there.’2 BRUTUS was asked a similar question on the same day and on 1st and 2nd August replied: All American forces destined for the Normandy operation, namely, the First and the Third American Armies, are included in the Twelfth Army Group, of which the head is General Bradley. There is also in Normandy the 21 Army Group, composed of the First Canadian Army and the Second British Army. The chief is General Montgomery. Both Army Groups come directly under SHAEF, of which the supreme head is General Eisenhower. It is possible that, in practice, Montgomery commands both Army Groups on the battlefield.’3 In the OKH Situation Report of 4th August we read: ‘It is thought that Lt. General Bradley has taken command of the American Twelfth Army Group in Normandy. General Montgomery retains his overall command of the operations in Normandy and remains Commander-in-Chief of the English 21 Army Group.’4

If the belief was to be sustained that the second landing would be on a scale comparable with that of the Normandy invasion, it was important that the Germans should continue to imagine that Supreme Headquarters were still located in England, for it would obviously be inconvenient to direct the second assault from France. At the beginning of August General Eisenhower established a small command post in France and it was unfortunate that the newspapers announced the Supreme Commander’s removal to the Continent on 10th August. On that day the Daily Telegraph reported: ‘Eisenhower Moves Across–HQ now in France. It was revealed last night that General Eisenhower, Allied Supreme C-in-C, had established HQ on the Continent to maintain the closest possible contact with the fast-rolling offensive against the German forces. His HQ unit was moved to Normandy by air in the past few days. Officers and enlisted personnel, including WACs, are living in tents in a camouflaged area under constant patrol by heavily armed military police. The general himself lives in a trailer under a 24-hours’ guard, during which a military policeman sits in a dug-out behind a machine-gun. Immediate telephone communication with Supreme HQ in London is available from the trailer. General Eisenhower’s quarters are near an airfield from which he makes speedy trips daily for personal conferences with General Montgomery and General Bradley. On Tuesday he saw his British and American field commanders. On Bank Holiday he conferred with Mr Churchill.’ The significance of this press release was not lost on the Germans. ‘For the rest we must count on the enemy command bringing over sufficient forces from Great Britain to ensure the full exploitation of his present success as the transfer of General Eisenhower’s Headquarters from Great Britain to France has also emphasised the decisive character of the operations in the later stages.’5 To compensate for this, however, the new FUSAG was gaining in strength and the appreciation continues: ‘The accelerated reinforcement of the FUSAG formations still in England from the United States seems to have started.’ At the same time GARBO did what he could to correct the impression which had been created by the report of the Supreme Commander’s departure. ‘4 (3) told me that, in view of the possibility of the immediate collapse of the German Army, the Allied Chiefs of Staff want Eisenhower to maintain the closest contact with Montgomery at the present time. For this reason a section of Supreme Headquarters has been transferred to the Normandy front with the category of Advanced Headquarters for those two Army Groups, but the structure of Supreme Headquarters remains here. He said that it was merely a question of establishing closer liaison between the headquarters of Montgomery and Supreme Headquarters. Also learned the following from him: the Commander-in-Chief of the two Army Groups fighting in France is Montgomery.’6 A few days later, the Germans, having stated that at the moment there was no evidence of any new landing operations in the Channel area, appreciated: ‘It must, however, be pointed out that the neutralisation of strong German forces in Normandy as well as the weakening of Northern France both in the forward and rear areas which is already known accurately by the enemy creates the conditions necessary to enable the enemy command quickly to put into operation again plans which have hitherto been postponed. In this connection the continued retention in Great Britain of strong airborne forces is noteworthy, formations whose employment is only envisaged within the framework of a new operational phase.’7 The ‘strong airborne forces’ referred to the new First Allied Airborne Army, whose formation had been officially announced on 10th August and about which more will be said later.

On 15th August through some misunderstanding between the Censorship Departments, it was announced that General Eisenhower was directing operations in the Argentan–Falaise sector. This was immediately contradicted by the SHAEF official spokesman. ‘General Montgomery still commands the 21 Army Group, under which is the Twelfth Army Group. This means that General Montgomery is over General Bradley, but both are under General Eisenhower as Supreme C-in-C, which always was the case. An announcement by General Eisenhower apparently caused the erroneous belief that General Montgomery had been removed from active command of all Allied ground forces in Western France. This is not the situation. It simply is not true.’8 The whole business caused a considerable stir On 17th August the Daily Mirror contained a strongly worded leading article demanding that an apology should be offered to General Montgomery and a cartoon suggesting indecision in high quarters. From the point of view of deception the contradiction was really worse than the announcement because it made it look as if we were trying to conceal something. This time, however, the incident appears to have escaped the enemy’s notice for it provoked no fresh comment.

Bearing in mind the importance which the enemy attached to our choice of commanders, we now felt it incumbent upon us to select commanders for the two fictitious armies comprised in the new FUSAG. For Fourteenth Army General Lucas was chosen. General Lucas was in the United States at the time. A press stop was placed on his movements and it was hoped that his true whereabouts would not become known to the Germans. For the Fourth Army the best that the Military Secretary could offer was General Morgan, the GOC-in-C of Southern Command. This choice was not altogether to our liking since Home Commands are not normally subject to the severe security restrictions which apply in the case of commanders of operational troops. There was always the danger that the activities of a General holding such an appointment might be reported in the press and so spoil our story. Fortunately there were at that time several Generals Morgan. We therefore hoped that it might be possible to keep the Germans in doubt as to which one it was. On 26th July BRUTUS had been asked: ‘Who is CO Fourth Army?’9 On 18th August, after his visit to the headquarters of the Fourth Army at Heathfield, he was able to tell them that General Morgan held that appointment.10 On 26th August the Germans asked GARBO: ‘Did you ever hear about a General named Morgan? If yes, what post does he occupy and which is his christian name?’11 And to BRUTUS on 13th September: ‘What are the christian names of the British General Morgan, Commander-in-Chief Fourth Army.’12 Both agents took a long time in answering. On 29th September BRUTUS came back with us: ‘With regard to General Morgan, I have twice, without result, tried to fall in with my FUSAG friends in London. Can you not verify it with the British Army List?’13 On 1st October GARBO explained: ‘There are the following Generals Morgan listed in Who’s Who: Major-General, temporary Lieutenant-General, Frederick Edgworth Morgan, born 1894; temporary Major-General Harold de Riemer Morgan, born 1888; Brigadier-General John Hartman Morgan, born 1876; Lieutenant-General Reginald Hallward Morgan, born 1871; Brigadier-General Rosslewyn Westropp Morgan, born 1879; temporary Lieutenant-General William Duthie Morgan, date of birth not given; General Llewellyn Isaac Gethin Morgan Owen, born 1879. The first of these was given a lot of press publicity recently as the chief planner of the invasion.’14 Doggedly the Germans came back to GARBO on 6th October: ‘Would like to know christian names of General Morgan Fourth British Army.’15 But neither GARBO nor BRUTUS had anything more to say on the subject.

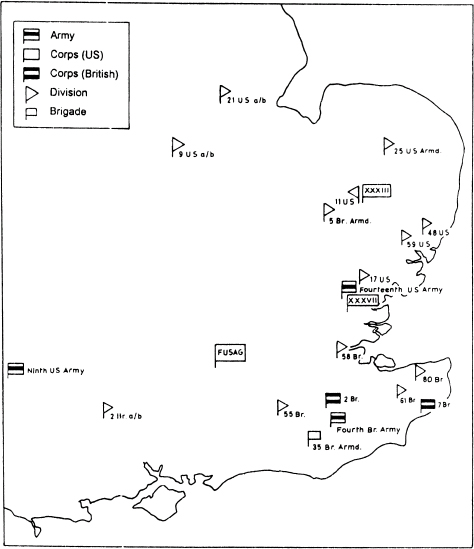

Throughout the month of August the planting of the new Order of Battle proceeded most expeditiously. It will not be necessary here to record the whole process in detail. By an examination of the relevant documents the progress of each formation can, however, be traced first in the agent’s message, then in the German Intelligence Summary and finally on the Fremde Heere West Location Map. The map of 29th August reveals practically the whole of the new FUSAG with all the locations, if not correct, erring by a few miles only.16 There are only two formations missing altogether, namely the 25th United States Armoured Division and the 35th British Armoured Brigade, but the former is accepted in the Intelligence Summary for 31st August, so that out of a total of one army group, three armies, four army corps, two armoured divisions, eight infantry divisions, three airborne divisions and one armoured brigade, all sham except for one army and two infantry divisions, only the armoured brigade is missing.

There is no evidence to show that all of this intelligence was not supplied by the two agents, GARBO and BRUTUS, possibly with some assistance from TATE. Yet it is interesting to note how very far we were from realising this at the time. At the beginning of August, when manpower shortage was becoming a matter of serious concern, an investigation was made with a view to reducing military establishments whose strength exceeded their needs. In defending the continued employment of the special units that were employed on wireless deception, the two battalions which were manning the dummy craft and a small party of about 200 men, who were still ‘lighting fires in woods, hanging out washing, &c.’, to animate the embarkation camps of South-Eastern Command, a letter from Ops (B) Sub-section concludes with the remark: ‘It is interesting to note from the foregoing that, after subtracting the personnel who are engaged on FORTITUDE on a “part-time” basis, the Fifteenth German Army, consisting of twenty-two divisions, is being “held” by a force of approximately 1,500 all ranks.’17

When we last examined the state of the German forces in France, we found that at the beginning of July there were twenty-two18 divisions north of the Seine. That was still the position at the middle of the month. During the following two weeks this total was reduced by two only. By 18th July the 326th Limited Employment Infantry Division had gone to Normandy and before the end of the month the 19th Panzer Division had left for Russia. It was not until the beginning of August that the landslide really began. It will probably be agreed that this was the result of force majeure rather than from any feeling that the danger of a second landing had been removed. By 6th August the 84th and 89th Field Divisions stationed between Le Havre and Rouen as well as the 116th Panzer Division had left for the bridgehead. There still remained seventeen divisions. During the next few days no fewer than five19 divisions were transferred to Normandy, leaving on 13th August a total of twelve. The SHAEF Intelligence Summary for 12th August tells us: ‘Fifteenth Army is now sending infantry divisions to West Normandy as fast as the railways, or more often bicycles and legs, can carry them. They seem to be arriving more or less in order of nearness: 84th and 89th Infantry Divisions, pocket divisions from across the Seine, arrived first, one on either wing, and the next batch, just arriving, all from the Pas de Calais, are 85th, 331st and, apparently, 344th Infantry Divisions, elements of all of which have been contacted. Moreover, the training divisions still remaining in the N.E. (182nd and 165th) are contributing generous drafts. The quality and morale of these latest arrivals are deplorable.’20 By 14th August the 48th Field Division had gone and by the 27th there remained north of the Somme an odd lot of one field and six limited employment divisions, two of the latter having just arrived from Germany as reinforcements.

Locations of FUSAG formations according to FORTITLIDE II.

Location of FUSAG formations given on the OKH map of 29th August, 1944.

Notes

1. Formations included by the Germans in FUSAG without our authority are omitted.

2. The reason for the incorrect location of Ninth US Army is considered in the text. This mistake was rectified in the Lagebericht of 31st August and, no doubt, subsequent issues of the OKH map were amended accordingly.

3. The 17th US Infantry Division though omitted from this map was accepted as being in the Eastern Counties in the Lagebericht of the same date.

On 7th August a Berlin broadcast stated: ‘Large-scale landing operations by the Allies need no longer be reckoned with, a German military spokesman declared today. Since the Allies are employing four armies in the invasion territory, Eisenhower has now concentrated his main forces in that area. The intentions of the Allies are now quite clear, and that is an advantage to the Germans. It is always easier to plan counter-measures when the opponent’s objective is apparent.’21 The German propagandist refrained from adding that it would have been easier still to plan counter-measures if the opponent’s objective had become apparent two months sooner.

Before recording the movements of German troops in South and South-West France during this period, something must be said about the threats which were now being directed against these parts of the French coast. It had been decided that the Seventh United States Army should invade the South of France on 15th August. To cover the landing a plan known as FERDINAND was put into operation on 7th July. The aim of FERDINAND was to convince the Germans that no invasion of the south coast of France would take place by finding alternative employment for the forces which had been assembled for the attack. Included among the several measures which were adopted in pursuance of that object was the threat of an amphibious assault by an American corps on the Gulf of Genoa in August. The Germans were also to be persuaded that one of the two French corps, which were in fact to take part in the landing, was under orders to proceed to England with two infantry divisions under command. On arrival it would also take command of the 2nd French Armoured Division which was in fact already in this country and about to go to France. The suggestion was to be made that the use of this French corps in Normandy would go some way to satisfy French opinion which would otherwise be disappointed by the cancellation of the Southern attack. This plan was operated from the Mediterranean. At the request of the Commander of ‘A’ Force TATE sent two messages at the beginning of August confirming the arrival of the French Corps in England.22 There is a satisfactory reflection by FERDINAND in the German Intelligence Summary for 4th August.23

On 5th July General Maitland Wilson24 requested SHAEF to simulate preparations for an attack against the Biscay coast, the threat to exercise its greatest effect immediately before 15th August with a view to holding German troops in South-West France, which might otherwise be sent to reinforce the Mediterranean coast.25 On the following day SHAEF replied that the request was being urgently examined.26 SHAEF was against doing anything of this nature. The possibility of making the threat convincing was felt to be remote and it was thought that the plan would be prejudicial to FORTITUDE SOUTH. A triangular correspondence between London, Washington and the Mediterranean ensued. On 25th July the Combined Chiefs of Staff informed the Supreme Allied Commander, Mediterranean Theatre, that they approved General Eisenhower’s recommendation that the ‘existent latent threat only to the Biscay coast be maintained’. It was not until 8th August that a plan, IRONSIDE II, was approved. The story was that operations by the Maquis in the South of France had proved more effective than had originally been expected. Generals Eisenhower and Wilson, in consultation with General de Gaulle, had therefore decided to exploit this by increasing the supply of arms and trained organisers to the Maquis in the Bordeaux–Bayonne area to an extent which would enable the whole organisation to take control of this area unsupported by large-scale amphibious operations. As soon as the ports of Bordeaux and Bayonne became untenable as a result of these operations the seaborne forces would be despatched from the United States to open these ports as bases for supplying the Maquis with heavy equipment. The target date was to be 14th August. The plan was to be put into operation by Special and Diplomatic Means.

In the early part of July there remained in the South of France one Panzer, one field and five limited employment divisions, and in the South-West of France one Panzer and four limited employment divisions. By 16th July the 716th Limited Employment Division, originally in the Normandy bridgehead, had gone to reinforce the south coast. Before 6th August the 9th Panzer Division, which had been in the South of France, was transferred to Normandy and its place was taken by the 11th Panzer Division which had been at Bordeaux. At the same time the 189th Limited Employment Division moved from the Hautes Pyrenees to Sete on the south coast of France. By that date therefore the south-west coast was reduced to two limited employment divisions and the forces on the south coast had risen to nine divisions, one Panzer, one field and seven for limited employment. That was the position when the landing took place.

Whether IRONSIDE II would have achieved anything even if it had been given a longer run may be doubted, but it is certain that when Special Means received its instructions on 8th August, any chance that there might have been of rendering assistance had already passed, since the only formation of any real value, the 11th Panzer Division, had already left for the south coast of France.