Chapter Nine

Can I Have Your Autograph…and More Butter?

Same thing with my wife, no respect. I took her to a drive-in movie. I spent the whole night trying to find out what car she was in.

People often ask me how I came up with my “no respect” line. When I got back into show business in 1961, I felt—for obvious reasons—that nothing in my life went right, and I realized that millions of people felt the same way. So when I first came back my catch phrase was “nothing goes right.” Early on, that was my setup for a lot of jokes.

It worked pretty well, but a few years later, the book The Godfather came out and it was a bestseller and then the movie came out, which was even bigger. Because of The Godfather, suddenly all anybody would talk about was “respect.” You’ve gotta show me some respect…If she’s with me, you show her respect…It’s all about respect…”

I realized that fit pretty well with the image I was now working with onstage, so I decided to come up with a joke that had the word “respect” in it. The first one I wrote was: “I get no respect. When I was a kid, I played hide-and-seek. They wouldn’t even look for me.”

I was working a place in Greenwich Village, Upstairs at the Duplex, when I first did that joke, and the crowd loved it. After the show, people came up to me and said things like, “Hey, Rodney, me, too—no respect.”

So I kept writing jokes off that line—“I don’t get no respect”—and it caught on more and more. Now I have probably written over five hundred “no respect” jokes. Here are a few of my early ones:

With my old man, I never got respect. I asked him if I could go ice-skating on the lake. He told me to wait till it gets warmer.

And the first time he put me on the roller coaster, he told me to stand up straight.

With girls, I don’t get no respect. I went out with a belly dancer. She told me I turned her stomach.

When I was a kid, my yo-yo, it never came back.

People also ask me, “What was your big break in show business?” For me it didn’t happen like that. Elvis Presley did one song on The Ed Sullivan Show and the country went crazy. I had no big break. It was a combination of a lot of things: sixteen Ed Sullivan Shows, seventy times on The Tonight Show, forty-five Merv Griffin Shows, twenty Lite Beer commercials, and owning a successful nightclub. Then twenty-five years ago, I did Caddyshack, which got me into movies.

Mine was not an easy road.

My image has its problems. People watch a guy degrade himself for an hour onstage, they get carried away and start to believe that it’s really me up there. And with my image of “no respect,” many people have treated me that way. One night I was doing a show at my club, and as I was about to walk onstage, a man sitting close by said, “Hey, Rodney, before you go on, do me a favor, will ya? Let me have your autograph—and more butter?”

One day I was taking a walk in Manhattan. A pretty girl recognized me and said hello. We got to talking, and she told me that she wanted to be a singer.

I didn’t want her to have unrealistic dreams. “Show business is tough,” I told her, “even for talented people. It’s hard for anyone to make it.”

And she said, “Well, you made it.”

I guess she figured that if I’d made it, anybody could make it.

One day I was with some people in the coffee shop at the Riviera Hotel in Vegas. The waiter told me that a couple at another table said they’d buy me a drink if I’d sit with them.

I told the waiter, “Find out how long I have to sit with them to get a steak.”

I was in another Vegas coffee shop having lunch with a few friends when I noticed that almost everyone in the place was staring at me. I was fairly popular then, but not that popular. I felt very ill at ease. I didn’t know what to do. I decided to wave every once in a while. After I’d paid the check and got up to leave, I found out why everybody had been “staring at me”—I’d been sitting under a huge keno board.

I was in a bar the other day, having a few shots, and they told me to get out. They wanted to start the happy hour.

My father’s funeral was one of the loneliest moments of my life. He was seventy-eight when he died.

I flew down to Florida for the funeral, and I was the only person there—my mother had died a few years earlier. Just as the guys with the ropes were lowering my father’s casket into the grave, a guy came up to me and said, “Hey, Rodney, can I have your autograph?”

When I decided to get back into show business, all my friends—and my father—told me I was nuts. He told me to get a regular job and forget show business. I’m glad that before he died he was able to see that I was successful.

A few years before, I was working in a nightclub called the Valley Stream Park Inn out on Long Island, and I asked my father to come along. This was way before I’d made it on Sullivan and The Tonight Show.

We walk into the club and see that they had a big party of four hundred people in the room. Only problem was that they were all Chinese. I said to my old man, “Look at this, will ya? All Chinese. What can I do here?” Of all nights to bring him, I pick this one. I knew I had a good act at that point, and I was really looking to impress my old man, but having four hundred Chinese people stare at me wasn’t going to do it.

The nightclub manager could see that I was disappointed, so he said, “Don’t worry. They are all college graduates and they all speak English. They’ll understand everything you say.”

He turned out to be right. They were a great audience and the show went great. I was so relieved that my father got to see me kill an audience.

Driving home, my old man said to me, “I think you’ve got something.”

My ol’ man was tough. He allowed no drinking in the house. I had two brothers who died of thirst.

It’s not just me. Everyone—at one time or another—gets no respect. The movie Fargo got no respect. A few years back, it was up for Best Picture with The English Patient.

I saw Fargo, and like most people, I thought it was great. I saw The English Patient and thought it needed a doctor. Like a lot of people I spoke to, I didn’t like the movie.

The Motion Picture Academy named The English Patient best movie of the year.

Now how could anyone who’d seen both those movies choose The English Patient over Fargo? I know how—it seems more sophisticated to like The English Patient. The name’s so classy—whatever it means—and the story’s so serious—whatever it was supposed to be about.

From day one, comedians got no respect from the Academy. Actors and actresses know that comedy is the toughest thing to do in show business…unless it’s birdcalls. Many comedians are great actors, but few actors can do comedy. But comedy never gets respect. Laurel and Hardy, W. C. Fields, Mae West, the Marx Brothers, Jack Benny, Jackie Gleason, Bob Hope—none of these legends ever won a regular Academy Award.

Yet when the Academy has their awards show every year, they get a comedian to host it.

I told my landlord I want to live in a more expensive apartment. He raised my rent.

About ten years ago, AT&T was trying to lure back customers who’d switched to other phone services. Their big ad campaign said, “Call AT&T and we’ll take you back.” All you heard was “Call us, we’ll take you back.”

So I wrote a joke about it. “I get no respect. I called up AT&T. They won’t take me back.” I did it on The Tonight Show, and it got a good laugh.

That gave me an idea for an AT&T commercial, so I got in touch with some big shot there and told her my idea. She said, “I like it. Let me think about it for a week.” A week later, she said, “Let’s do it.”

AT&T changed its mind four or five times over the next six months. I found out they took many surveys about whether people liked me, and asked them if they thought I would be good to do commercials for AT&T.

Finally, they called me and said, “Okay, it’s definite. We’re doing the commercial. We’ll start right away.”

But I had a problem. I couldn’t start right away. I had to check into the hospital. I had an abdominal aortic aneurysm, which forced me to have a very distasteful operation. They cut my gut open, took all my intestines out, and put them on the table while they fixed my aorta. When they were finished, they stuffed all my intestines back in and stitched me up. For the next three or four months, I was in constant pain while my intestines shifted around, trying to settle.

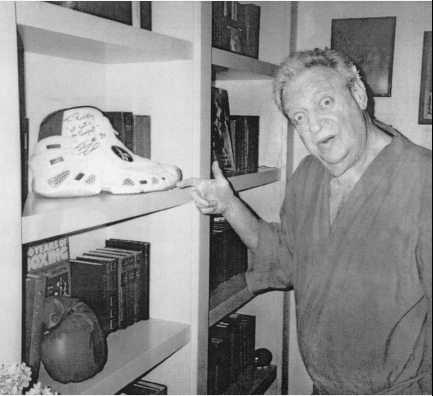

One day, I was out on my balcony in L.A., and I saw my new neighbor, Shaquille O’Neal, on his balcony. We gave each other a wave. The next day, he sent his calling card: one of his size 22EEE shoes, inscribed To Rodney, I gets no respect—Shaq.

Courtesy of the collection of Rodney Dangerfield.

I called the woman at AT&T and told her I had another “project” I was working on and had to finish it. I figured it would take about four weeks. She told me to call her as soon as I was free.

As soon as I was feeling myself again, I called AT&T and said, “Let’s get going.”

They flew a fellow from their New York advertising agency out to L.A., and he and I wrote two commercials in two days.

We liked them, AT&T liked them, we were set. I shot both commercials in one day.

A few weeks later, AT&T ran the commercials on TV, and they were a huge success. AT&T then got full-page ads with me in all the major newspapers, and radio, too. Almost immediately, the business started coming in. Everybody was happy, happy, happy.

They paid me well for the six months of that campaign, so I was planning to do some more. I had two more ideas ready, and the fellow from the ad agency was set to fly out to L.A. again to help write them.

Then out of the blue I got a call telling me there was some kind of problem. So I called the nice lady at AT&T, who told me that one of the company’s big stockholders didn’t want me in any more commercials because—he said—I wasn’t dignified enough to represent AT&T.

Okay, I figured. That’s that.

The other night I turned on my television and saw another comedian doing an AT&T commercial—someone I guess they think is more dignified—Carrot Top.

I tell ya, my wife was never nice to me. On our first date, I asked her if I could give her a good-night kiss on the cheek. She bent over.