Chapter Eleven

A Night with Lenny Bruce

With sex, my wife thinks twice before she turns me down. Yeah, once in the morning and once at night.

Hanging out with Jack Benny and Johnny Carson—you can’t do any better than that. But my first brush with fame was back in the early forties, when I did a show with Al Jolson.

I was working at a nightclub in Atlantic City called the Paddock. One night the boss told me that Jolson was in town doing a benefit show and needed a couple of acts to go on before him.

I said, “Sure.” Anything to be on a stage with Jolson.

A few hours later, I was backstage in a theater looking at Jolson standing in his underwear, reading a telegram. He was disappointed. He said, “Why couldn’t it be from a girl?” It’s been rumored that Jolson liked to have sex before he did a show. Apparently that night he struck out.

Even stars can’t get lucky every night.

The day my wife and I got married—that was a beauty. I gave her the ring and she gave me the finger.

A few years later, I was working at a nightclub called the Queen’s Terrace on Long Island. One night Jackie Gleason walked in. He sat down at a table all by himself and watched the show while he drank a whole fifth of Scotch. Then he got up, gave the waiter a $20 tip, and walked out, straight as an arrow.

Gleason had quite a reputation as a drinker, and he liked to enjoy himself. He proved that night that he could do both. Jackie had an appetite for other pleasures as well.

One night I was in Bobby Byron’s room at the Belvedere Hotel with Joe E. Ross. There was a knock on the door.

Bobby yelled, “Who is it?”

I heard a voice say, “The Great One.”

Gleason called himself “The Great One,” and he was worthy of the title.

Bobby opened the door and did a little business transaction—he sold the Great One some great pot. And away we go…

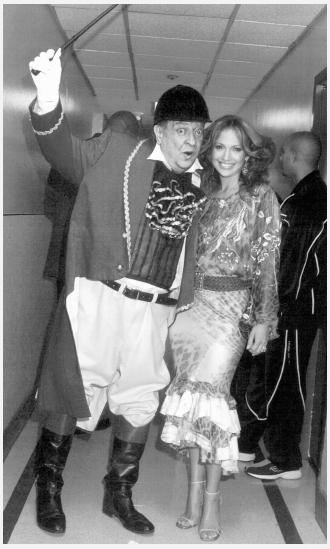

I went fox hunting…look what I found.

Courtesy of the collection of Rodney Dangerfield.

Hey, I gotta be honest with you. I’m not a fabulous lover. My wife and I were in bed on our wedding night and she said, “Well, honey, this is it.” I said, “Honey, that was it.”

I first met Lenny Bruce through his mother, Sally Marr, who was the mistress of ceremonies at the Polish Falcon Club, where I worked as a singing waiter back in 1942. As the years went on, I became friendly with Lenny—we saw each other here and there and hung out. This was years before he had an act, or even knew he was going to have an act. Lenny was the nicest kid in the world, and he idolized Joe Ancis, one of my oldest and dearest friends. I’ll tell you a lot more about Joe later.

Lenny hit it big in the fifties. One time I was hanging out with him in his room at the American Hotel in New York. He was getting ready to do his act at a club in the Village, but first he had to shoot himself up. Even then—young, smart, and at the top of his game—he had a bad heroin habit.

It was difficult for me to watch as he held that needle, looking for a good vein in his arm, so I went into the bathroom until he had finished. When he was done, he was a new man. He said, “Tonight I’m going to do the show dressed in white—completely white, everything.”

After he became the man in white—white pants, white shirt, white jacket, white shoes, white socks, white underwear, far as I can remember—we went down to the club.

Here are the first words Lenny said that night when he took the stage: “Tonight, here’s how I’m going to open my act. I’m going to pee on you. If a guy tells jokes, you’ll forget him. But if a guy pees on you, you’ll never forget him.”

A guy in the audience yelled, “Keep it clean. Keep it clean.”

And Lenny answered him in these exact words: “Fuck you, Jim, you square motherfucker!”

We were poor, too. If I wasn’t born a boy, I would have nothing to play with.

Redd Foxx was another good friend of mine. He was a great comedian, a “natural,” as they say. (I’ve learned over the years that when you get to know the “naturals,” you find that they work very hard at their craft.) Here’s one of my favorite Redd Foxx jokes: “China has over a billion people. Let’s face it—they outfucked us.”

One time, when I was very tense and had been working at my club nonstop, I needed to get away, so I called around to find out where Redd was performing. He was working in Florida, so I flew down to see him. My first night there, I put so much stuff up my nose that when I went to sleep at eight in the morning, I said to myself, If I wake up, it’s a gift.

Later, I was doing a TV special for ABC, and I wanted Redd to be in it. He was working in Las Vegas, so we had to fit it into his schedule. In show business, if you’re not working one night, they say you’re “dark” that night, so I said, “Redd, are you dark on Monday night?”

Redd said, “Rodney, I’m dark every night.”

In the 1980s, I did three comedy specials for ABC in L.A. We did one of them during the summer, so I rented a house in Malibu.

My next-door neighbor was Flip Wilson. We would sometimes hang out at night and swap stories. Flip told me a disturbing story from when he was an unknown working in the South.

Flip had just closed in one city, and a man he’d met at his hotel told him that another guest was driving to the same city Flip was going to next, so Flip asked the guy for a ride.

The guy said okay, so Flip got in the car and off they went. After they’d been driving for a while, the guy said, “What kind of work do you do?”

Flip told him, “I’m an entertainer.”

The guy said, “All niggers are entertainers. What do you do for a living?”

I first saw Andy Kauffman at a club in New York called Catch a Rising Star. What amazed me was that Andy did two shows each night, each one completely different. For the second show, he’d come out as this obnoxious character, and the audience never knew it was Andy doing both spots.

I immediately became a huge Andy Kauffman fan and asked him if he’d like to open for me on a couple of dates. He said okay, so we went to work at a theater in San Francisco.

Andy made life interesting, on and off the stage. Onstage, his thing was to get the audience to hate him. He did an amazing character, a repulsive singer named Tony Clifton, who told vile jokes and said nasty things about women and insulted everybody. And the audience hated him—they’d curse him out and even throw things at him. And that’s exactly what happened on our opening night in San Francisco.

They threw so much stuff at Andy, when I came on it looked like I walked into a salad bar.

The next night, the theater manager was prepared—he put up a net that covered the entire length of the stage to protect Andy from people throwing things. It worked pretty well—only two things got through the net and hit Andy: an apple and a hard-boiled egg.

I loved it, and Andy loved it. He was behind the net with thousands of people yelling at him, “Get off! You stink! Get off, you bum!”

Andy, still in character as Tony Clifton, raised his hand to get the audience to be quiet and said, “There are a few of you out there who are ruining it for the rest of us.”

People said to me, “What are you doing with him as your opening act? You need someone who puts people in a good mood. They hate this guy.”

I said, “No, he’s different. I like him.”

My second date with Andy was at the Comedy Store in Los Angeles. Before the show, Andy had the emcee make this announcement: “Ladies and gentlemen, Tony Clifton asks that there be no smoking during his performance.” There was some grumbling—remember this was thirty years ago—but people put out their cigarettes.

About five minutes later, just as the show was about to start, the announcer once again said, “Ladies and gentlemen, please remember that when Tony Clifton is on, there can be absolutely no smoking during the show.”

Then he introduced Andy as Tony Clifton—and Tony walked out smoking a cigarette.

You know you’re drunk when you take a leak and your fly isn’t open.

In 1985, HBO offered me a deal to do a show from Dangerfield’s that would introduce new comedians. They told me I could pick the comedians.

I liked that idea because I’ve always been looking out for new talent. I was always attracted to the edgy comics—like Andy Kauffman and Sam Kinison.

I did an HBO show every year for six or seven years, and they were a big hit with viewers, and with comics. Most of the young comedians I contacted wanted to be on my shows. Many times, it was their first shot on national television, and it led to bigger things for a number of them. Here are some of the people I introduced on those shows: Jerry Seinfeld, Robert Townsend, Roseanne, Bob Saget, Louie Anderson, Andrew Dice Clay, Carol Liefer, Rita Rudner, Jeff Foxworthy, Tim Allen, and Sam Kinison.

He who laughs last didn’t get the joke in the first place.

About Fifteen years ago I was working at Caesars Palace in Vegas. My opening act was a girl named Pam Madison, who sang and did impersonations of singers. I’d never worked with her, so before our first show, I asked her what her closing number was. The opening act usually does about a half hour, but I wanted to know a little more precisely when I had to be ready to go on. She told me she always closed as Barbra Streisand singing “People.” Okay, fine.

So, opening night, I’m in my dressing room, just pulling myself together as Pam goes on for the first show at eight. I hear her introduced, I hear the applause, whatever…I stop paying attention. The next thing I know, I hear Pam doing Barbra Streisand singing “People”! I’m confused as hell, so I look at my watch. It’s only eight-twelve! She’d only been on for twelve minutes! So I frantically tie my tie, put my shoes on, and run toward the stage.

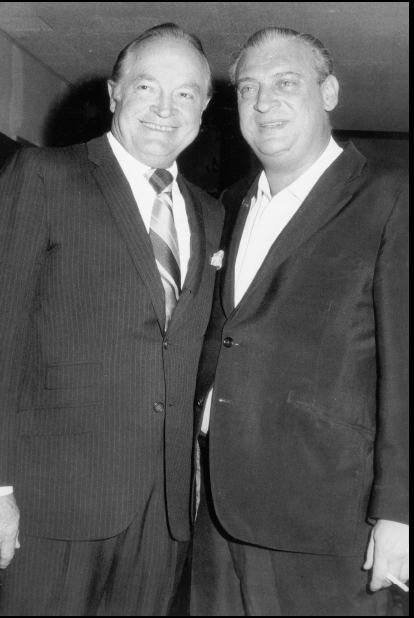

Bob Hope entertained the troops every year. So did my wife.

Courtesy of Dangerfield’s, New York

After the show I asked Pam what had happened. She told me, “I saw everyone in that audience looking at me and I panicked. I had to get out of there.”

She settled down by the next show, and we got along great. One night after the show, Pam introduced me to a friend of hers who was working at a comedy club next door. It was Roseanne Barr, who was an unknown at the time. The three of us sat and talked for a while and I could see that Roseanne was very funny. I also thought, What a voice! She’d be the perfect wife to abuse me.

Before we parted, I told Roseanne that I was doing one of my HBO comedy shows in a few months and I’d like her to be on it. I told her that I wanted her to do her stand-up act, and that I’d also write some skits that she and I could tape for the show. She said, “Sure, whatever,” but didn’t seem too excited.

Three months later, I called her and said it was all set—skits were written and I was sending her a copy of the script for her to look over. Roseanne now got real excited and told me, “This is the first time someone told me they were going to do something for me and they actually did it!”

As you might have guessed, Roseanne was a hit, even though it was a big show—I also had Jerry Seinfeld, Sam Kinison, Robert Townsend, Bob Nelson, and Jeff Altman on that night.

Roseanne and I stayed friendly. Years later, in the early nineties, we hooked up at the Pritikin Longevity Center in Santa Monica, which was where people used to go to lose weight and get healthy. We spent a week there with Carl Reiner and his wife, Estelle. We all shared the same table for our meals and we had plenty of laughs, but one night Roseanne and I were having such a good time, laughing so hard about the awful—HEALTHY—food they were serving us, that we both flipped and decided to escape for a night. After we finished our dinner at Pritikin, which was not very tasty, we decided to go out and really eat. We both went nuts and ate all the junk we’d been craving all week.

My wife can’t cook at all. I got the only dog that begs for Alka-Seltzer.

I met Mike Tyson a few times, at the clubs and in Vegas, and he was always very nice to me. He’s not as scary as he looks, at least to me. Maybe that’s because I made him smile the first time we met. I looked him in the eye, real concerned, and said, “If anybody bothers you, let me know.”

I live in a bad neighborhood. Last week they raffled off a police car, with two cops still in it.

I once had a press agent named Lee Solters, who thought he was a big shot. He’d been Frank Sinatra’s publicist for thirty years, so maybe he was. Anyway, I noticed that whenever I talked to him on the phone the conversation always ended the same way. After a few minutes he would say, “I gotta hang up. I got a call coming in from overseas.” The first few times I believed him. Then I realized that this was his way of ending the conversation…and to make himself look like a big shot. After that, I would end our conversations by saying, “I gotta hang up. I got a local call coming in.”

What good is being the best if it brings out the worst in you?—LADYBUGS, 1992

In L.A., about fifteen years ago, I ran into a guy named Ron Jeremy, a porn star who grew up in New York. He was a smart guy, funny, and I took a liking to him. Even put him in one of my HBO skits. One day he said, “You know, Rodney, I really want to move back to New York. The people in L.A. are too crazy.”

Now, Ron Jeremy first became famous for a movie in which he said to a girl, “How about a blow job?” and she blew him off by saying, “Why don’t you give yourself a blow job?” He said, “Not a bad idea,” and went down on himself.

It was a wild thing, and people talked about it. That’s how he became famous.

That’s why I broke up when he said he wanted to move to New York—a guy who makes a living going down on himself thinks people in L.A. are too crazy.

Last week, I went to a discount massage parlor—it was self-service.

Speaking of big movie stars, I first met Dustin Hoffman at my club back in the early seventies. He was about to play Lenny Bruce in Bob Fosse’s movie and he wanted to get the feel of a nightclub and of doing stand-up. So he came over to Dangerfield’s and hung out for a week—although I told him, “You can’t learn to do stand-up in a week. You have to walk the boards for twenty years.”

One night Joe Ancis, who was Lenny’s longtime friend and mentor, dropped by to say hello. In the course of our conversation, Dustin said to Joe, “Do you think I’ll make a good Lenny Bruce?”

Joe said, “No.”

Dustin wasn’t exactly thrilled to hear that, but I told him, “Don’t worry about it. Very few people ever saw Lenny work, so no one will know the difference. Whatever you do, they’ll figure that’s Lenny.”

Dustin went on to win an Oscar nomination for Lenny.

One of the most talented guys I ever saw was Sam Kinison. I first met him in the early eighties when I was working in a place called the Arena, a theater-in-the-round in Houston. After the show, a few of us went to a local comedy club.

The show was Sam and two other young comics. He was young, raw, but had something wild that I liked. After the show, I asked the club manager, “Can I meet the guy who went on second?”

They brought Sam over to our table, and we talked for about fifteen minutes. He told me he was struggling with his act, but I told him, “You’ll be fine. You’re great.”

Sam had a crazy background—he’d been a preacher and came from a family of preachers. So there was plenty of anger and turmoil in him, which came out brilliantly onstage. Hilarious—but full of obscenities and rough talk about sex and drugs and religion. Sam didn’t hold back. He was raw, and honest, and very funny.

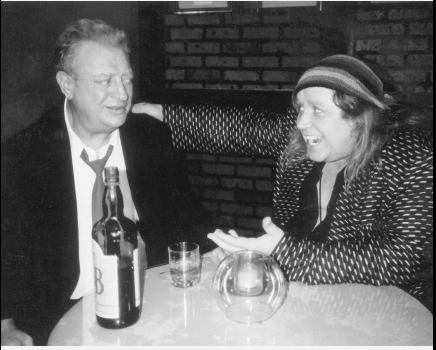

Here’s Sam Kinison giving me a lecture on how to handle women.

Courtesy of the collection of Rodney Dangerfield.

I met him again a few years later in New York at Catch a Rising Star. After we said our hellos, Sam said, “Rodney, I finally got it, man!”

So I stayed for his act, and he was right. He really did have something. His material was still wild, but his delivery was now mature. He was sensational. Sam, who’d been divorced three times, said he wasn’t going to get married again—“I don’t have to give away everything I own every five years!”

After that show, I said to him, “Jeez, you’re great, man. I’m doing an HBO show. I’ll put you on it, okay?”

He said, “No. That format’s no good for me. I can’t do just six or eight minutes like that. I need more time. I can’t cook until I’m out there at least ten minutes.”

I said, “You’re wrong, man. You can cook as soon as you walk onstage. Just go right into it.”

“I don’t know…” he said.

Sam went back to California, and two weeks later I got a phone call. It was Sam, and he was very excited. “Rodney,” he said, “I’m cookin’ right away now! Can I still get on your show?”

I said, “You got it.”

So he came out to New York and did my show, and he was hilarious. That’s when he did his now-famous Ethiopia joke. The papers were full of stories about a horrible famine in Ethiopia, so Sam said: “Hey, I’ve figured out why you people are starving—you live in a fuckin’ desert! See this? This is sand. NOTHING WILL GROW HERE!”

After that show aired, Sam started packing places that seat four or five hundred people. He used to say that that HBO show was “the six minutes that changed my life.”

About a year later, I said to Sam, “I’m doing another special. Kill ’em on this one and you’ll be playing two-thousand seaters.”

But I was wrong.

He did the show and killed ’em again. The next time I saw Sam he was headlining at the Universal Amphitheater in Los Angeles. Six thousand seats—packed—and everyone yelling, “Sam! Sam! Sam!”

Sam once told some writer that “Rodney is like a god to me.” That touched me deeply…but he probably said it because he thought I’d saved his life, not his career. Let me explain.

Before that second HBO show, Sam and his brother Bill came to see me. They were very worried. They said Sam had pissed off some Mafia guy who was now after him. They thought this guy was going to kill Sam.

I said, “Ah, I don’t know about that…” I’d met plenty of Mafia guys, and I was pretty sure Sam had nothing to fear. So I told him, “You got nothing to worry about. Concentrate on your show. The guy’s just trying to scare you. I’m telling you, nothing’s going to happen.”

Sam said okay, and he felt better. And of course, nothing happened to him. But because I had been so sure that nothing was going to happen, Sam and his brother got the idea that I had made a phone call to someone in the Mafia. Sam and Bill were now under the impression that I was connected, that I was “mobbed up.”

If you never saw Sam’s act, do yourself a favor and buy one of his albums, or all of them. Sam had a rather strange sense of humor. When his father died, Sam’s mother was very morose. To console her, Sam said, “Ma, look at it this way. You’ll have more closet space.”

Sam had a lot of great bits. Here’s one: “Today, everybody’s sick. They even have dog psychiatrists. I’d like to get in on that racket. ‘What’s that, Mr. Raven? I’m sure Spot’s a good boy. Let me take him inside and talk to him for a few minutes. Wait here. I’ll see what I can do.’” Then Sam would walk to the other end of the stage and pretend to open and close a door. Then he would yell at the imaginary dog, “What the fuck are you doing? Behave yourself! You’re a fucking dog! You shit in the street.”

When Sam got hot, I told him to make sure he only worked in places where he could be himself, where he didn’t have to censor himself. “You’re a big hit on HBO,” I told him. “But if you go on network television, they’ll be cutting you and cutting you. ‘You can’t say this, and you can’t say that.’ It’ll drive you crazy.”

So I suggested that he stay with HBO. I said, “The audience will find you.”

About six months later, Sam’s manager convinced him to do Saturday Night Live. He said, “It’s Saturday Night Live! How can you turn it down?”

So Sam did it, and he had huge problems with the censors for doing two bits that the network guys had told him not to do. One was about the drug war and the other was about Jesus getting nailed to the cross.

Since the show was live from New York, people on the East Coast saw Sam’s full performance, but his bits were cut for the rest of the country.

Sam wasn’t just banned from Saturday Night Live, he was banned from NBC, which meant no Tonight Show.

That would have killed the career of a lot of comedians, but it didn’t hurt Sam. He just kept rolling.

If you saw my movie Back to School, you’ll remember Sam as the crazed Vietnam vet–history professor. As soon as I knew the movie was a go, I wrote a part for Sam. He exploded on-screen, as I knew he would.

Sam was killed in a car accident while driving from L.A. to Vegas in 1992. He was just thirty-eight.

I went out to L.A. for the service, to pay my respects. He was lying there in a coffin and it was so strange, because the morticians had made him look so peaceful. He seemed to be smiling—like he was happy to be in that damn box.

I looked down at him, lying there, and just to make sure, I, like an idiot, whispered, “Sam…? Sam…?”

He didn’t move.

I thought to myself, He’s either dead—or very snobbish.

Thinking about Sam dying and movin’ on reminded me of one of his very best bits:

Up in heaven they asked Jesus to come back down to earth. They said, “C’mon, Jesus, it’s been two thousand years. Why not go back down, spread a little peace and joy.” And Jesus says, “Sure, man…JUST AS SOON AS I CAN PLAY THE FUCKIN’ PIANO AGAIN!”

I first met Tim Allen when he came to New York from Detroit to audition for one of my HBO specials. He was very funny and I wanted to put him on the show, but I screwed up—I had too many guys I was obligated to use for that show. When I told Tim, he took the news like a gentleman. When we did the next HBO show, he was my first call.

Years later, he was a big star, with his own sitcom, Home Improvement.

Tim is not just a guy who tells jokes. He proved himself to be a very good actor.

When I did a guest shot on Tim’s show, I felt funny talking money with Tim’s people, so I said to the show’s producers, “I tell ya what. I don’t want to hassle with lawyers and things. Tim knows me, so pay me whatever you think is fair.”

Okay. Good. Everybody’s smiling.

I do the show, everything is great. But when they gave me my paycheck, it was much lower than what I had expected. I didn’t think they had been fair, but I forgot about it.

A few months later, Disney—which owned ABC and Tim’s show—came to see me about a project. We did our business, and then I said, “Let me ask you something. Do you think what you paid me for Home Improvement was fair?”

“There’s nothing we can do about it now,” they said. “What’s done is done.”

“I tell ya what,” I said. “The raincoat I wore on the show was nice.” Some shows will give you your wardrobe, but not Disney. They keep it all. I said, “Leave the money where it is, throw in the raincoat, and we’ll call it even, okay?”

They said, “Fine.”

A week later, they sent it to me. It turned out to be an Armani.

Now I’m the only flasher with a $5,000 raincoat.

My wife has a temper. She keeps yelling at me, “You’re an animal, an animal!” So I took a leak in the living room and I told her from now on that’s my territory.

I first met Jim Carrey when I was working in Toronto, back in the early eighties. Someone told me to catch a young local comic who had something special. They were right.

Jim was about nineteen or twenty then, which means we’ve now been friends for more than twenty years.

Anyway, I caught his act in Toronto, and I thought he was fantastic. His mimicry was wild, and he had a rare gift for physical comedy. I saw he had talent to burn, and when he smiled you had to love him. So I hired him to open for me on a few dates.

He did a few one-nighters with me in Canada, and then I took him to Las Vegas to open at Caesars Palace.

When Jim first started working with me, he was mainly an impressionist, a sensational one. Who else can take his face and make it look like Mao Tse-tung, Brezhnev, Clint Eastwood, and Sammy Davis, Jr.?

But Jim wanted to stop doing impressions and be himself onstage. I could relate to that, because I’d gone through the same kind of thing as a young comedian. I used to do an impression of Al Jolson singing “Rock-a-bye Your Baby.” It was good enough that I would close my act with it, but I got to the point where I had to lose it, because I wanted to create my own voice, my own identity onstage.

So I understood what Jim was trying to do with his act, and I knew that it wouldn’t be easy. When he stopped doing the impressions and just did his bits, it didn’t go over with the audience. He was bombing every night.

Most headliners would say, “I gotta get a guy who gets laughs.” But I just said, “You’re great, Jim. Don’t worry about it.” I knew Jim had something special.

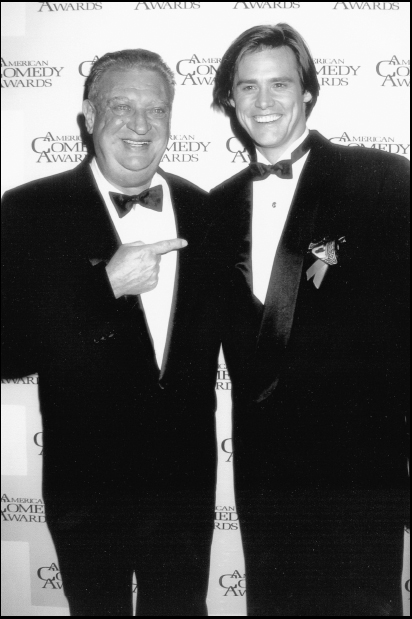

I have no respect left. I gave it to Jim.

Courtesy of the collection of Rodney Dangerfield.

In 1994 the American Comedy Awards honored me by giving me the Creative Achievement Award. Jim Carrey was very gracious when he accepted the task of introducing me and presenting me with the award. I was very moved by his words. His introduction of me was one of the highlights of my life.

I live in a rough neighborhood. One night I was held up, but the guy had class. He used an electric razor. This guy, he took my watch, my wallet, and a little off the sides. Actually, I blame myself. I was standing right next to an outlet.

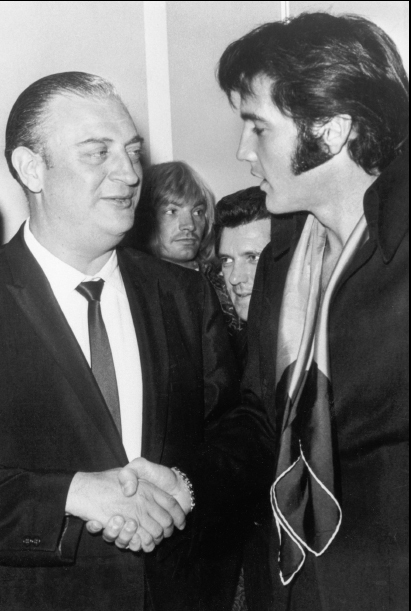

People often ask me what it was like to meet Elvis Presley. While I was working at the Sands in Las Vegas back in the late sixties, I got an invitation to attend Elvis’s closing-night party at the Hilton Hotel. So when my show was over, I went to the party.

Elvis was very warm and friendly. He walked in and said, “Hey, man.”

I said, “Hey, man.”

With our “Hey, mans” out of the way, we had somebody take a picture of us, and we chatted awhile.

I still have that picture on the wall at my club, which is why Dangerfield’s has the distinction of being the only nightclub robbed over two thousand times. When Dangerfield’s opened, we put that picture of Elvis and me on the wall in the bar area, along with the many other pictures of me with big shots. That picture has been stolen at least once a week—more often during prom season. In fact, the club has been open over thirty years and that’s the only picture that has been stolen.

One night I was standing in the bar area and a girl said, “Hey, Rodney, can I take a picture?” She was kind of cute, so I straightened my hair and my tie and said, “Sure, honey, go ahead.” She said, “Thanks,” grabbed the Elvis picture off the wall, and walked out.

I was working at the Tropicana Hotel in Vegas in the seventies when those Elvis impersonators became so popular. During that period there were ten Elvis impersonators working on the Strip at the same time. You didn’t even have to look like Elvis—if you wore an Elvis outfit and sang an Elvis song, you were a big hit.

One night I went backstage to visit an Elvis impersonator before his show. This guy was fat and very unattractive, but I heard him tell somebody, “The girl I want you to bring back after the show is the third girl I give a rose to.” Then he grabbed his guitar and waddled out to a screaming audience.

This photo’s been stolen hundreds of times from my club. I told Elvis it was a real kick to meet him. So many people tell me we look alike.

Courtesy of the collection of Rodney Dangerfield.

Years ago, when you spent $25 to see a show, you saw a star. Today, you pay $50 to see someone impersonate a star.

My wife and I, we both love Las Vegas. She likes to play the slots, and I like to play the sluts.

I met Barbra Streisand when I was tapped. It was at Elvis Presley’s party in Vegas. I was sitting at a table talking to a couple of guys. All of a sudden I felt a tap on my shoulder. I look up and it’s Barbra Streisand.

She was very nice. She said, “Rodney, I just came over to say good night.” She was about to leave.

I said, “Barbra, remember the Bonsoir in Greenwich Village? That was the first time I saw you.” I recalled the story to her.

I was there with a friend of mine. We were ready to go home when the maître d’ said to us, “There’s a girl auditioning now, and I hear she’s very good. You might want to see her.”

I said to my friend, “I tell you what. We’ll get our coats, we’ll stay for one song, and we’ll cut.”

She came on, and about forty minutes later we were still standing there holding our coats in our arms. We were mesmerized by the voice and the whole thing. That’s the first time I saw Barbra.

The next time, they’re having a show in New York—a benefit show in Barbra’s honor—and they asked me to be on the dais. So I do about four or five minutes. One of the jokes I told was about that night:

The first time I saw Barbra at the Bonsoir, it was a very unusual evening for me. It was the first time I went over the minimum.

I met President Reagan when I performed for him at the Ford Theater in Washington. Prior to the show, we all went to a reception at the White House, where I had my picture taken with both the president and Nancy Reagan.

After the show, I didn’t feel like hanging out with the senators, governors, and all the other political big shots—I got high on some shit and went outside and hung out with the limo drivers. I figured I had less chance of getting in trouble out there.

The next day I showed the picture of me and the Reagans to my housekeeper Thelma. I said, “Hey, do you know this couple right here?” She looked at the picture. Her eyes got real big, and she said to me, “Did you meet them in person?”

I was hoping to show the president how to inhale, but I never got the chance.

Courtesy of the collection of Rodney Dangerfield.

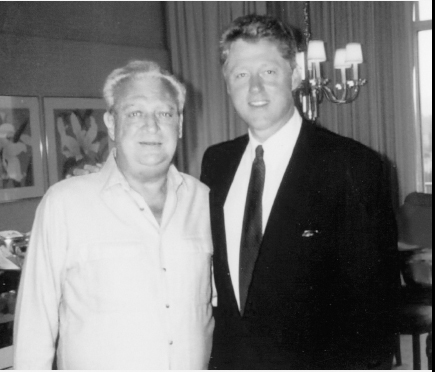

President Reagan wasn’t the only president I met. I like to tell people that President Clinton slept on my floor. In the nineties, I was living at the Beverly Hilton Hotel when Clinton came to L.A. for a speech. He decided to stay in my hotel that night, so they gave him a suite on the eighth floor, the same floor I was on.

The Secret Service said that no other guests could stay on the eighth floor because the president was sleeping there. They had moved all the other guests out, and were getting ready to evict me, but Clinton said, “Rodney doesn’t have to move. He’s okay.”

I thanked him, and we had our picture taken together. He was very cordial—we chatted about fifteen minutes. When I got back to my rooms, though, the Secret Service was there. They had two dogs running around, sniffing everything. I had some pot in my place, so I was sweating it out.

I got away with it. And I tell ya, these dogs, they were hip. On the way out one of them winked at me.

I tell ya, the dog drives me nuts. Last night he went on the paper four times…three times while I was reading it.

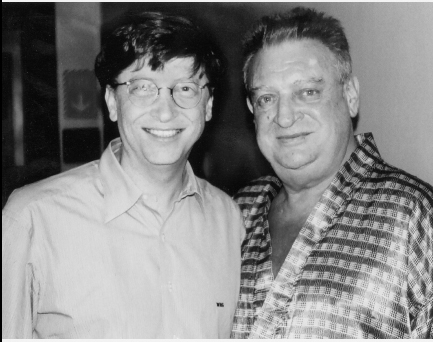

I did The Tonight Show one time when Bill Gates was on. Before the show, he told me he was a little nervous.

I said, “Bill, what are you worried about? You just have to talk. I have to get laughs.”

I wanted to befriend him. I felt like saying, “Bill, come on, will ya? You got billions and billions. What do you say you give me one billion? Do me a favor, okay? I’ll owe you one. What’s it mean to you? I’ll do things for you. I’ll get you girls, anything. I know the best massage parlors. You won’t be sorry. I know the right people. A friend of mine runs an all-night crap game.”

Nothing works out. I bought an Apple computer. There was a worm in it.

Here I am alone with Bill Gates. The girls never showed up.

Courtesy of the collection of Rodney Dangerfield.

It’s strange how getting up in front of a big crowd brings out fear in some people. To me it was never that difficult. I started in amateur shows when I was seventeen, and I’ve been doing it most of my life. But most people would fly to the moon before they’d stand up on a stage all by themselves and try to make people laugh. I know that for a fact. I was working at the Sands Hotel in Las Vegas, and after the show, Neil Armstrong—the first man to walk on the moon—came backstage to say hello. We shook hands and he said, “Wow, I wouldn’t want your job.”

I told him, “I wouldn’t want your job either.”

When I was a kid, I got no respect. I was kidnapped. They sent my parents a piece of my finger. My old man said he wanted more proof.

Back around 1995, people started saying to me, “Adam Sandler keeps talking about you in all his interviews.” He would speak very favorably of me.

I’d never met Adam, so I was touched.

I finally got to know Adam when he asked me to be in his movie Little Nicky. I had a very small part, but Adam and I got to hang out a bit. He told me that when he was fourteen years old his father took him to see me at the Sunrise Theater in Fort Lauderdale.

Recently I was extremely honored when Adam presented me with the Comedy Idol Award at Comedy Central’s award show, the Commies.

I like Adam, and I like his comedy. I think Adam and I are the only comedians today who have a clearly defined image. You can be a big star without having an image—Jim Carrey proved that—but Adam Sandler has an image that really works. In his movies he’s a likable lug, and you’re rooting for him when things go wrong. And when he finally wins at the end of the movie, he wins for everybody.

Adam gets involved in all the aspects of his movies, the writing, the directing, the casting, the producing, and all of his decisions are right on the money. I wouldn’t be surprised if someday he owns his own studio.