Chapter Fourteen

Three Lucky Breaks

I’m at the age now, when I meet a woman sixty years old, she’s too young for me.

Let’s face it, I’m getting old. That’s bad enough, but in the last few years, I’ve had four major operations. I’ve been cut up so many times, I feel like I’m back in my old neighborhood.

Before each operation I’ve had, the same thing always happens. As I’m lying on the gurney, the doctor comes over and he smiles at me. The smile says, “Don’t worry. I know what I’m doing. Have confidence in me.”

I always tell the doctor, “If I don’t make it, I’ll never know it.”

My first major operation was in 1992, to fix an abdominal aortic aneurysm. That was serious—if your aorta goes, you go. Most people die in minutes. Lucille Ball, George C. Scott, and Albert Einstein all died of ruptured aneurysms.

When a doctor catches it in time, it’s often discovered by accident. That’s what happened with me. One day I woke up and had some pain on my right side. I went to the doctor and got an X-ray. As the doctor had suspected, the tests showed that I had pancreatitis. But they also showed something the doctors really didn’t like—an aneurysm. So I had the surgery—what they call “the open procedure.”

Here’s how that goes: First they cut you open from your diaphragm down to your “ecstasy rod.” Then they take all of your intestines and put them on a table next to you. Then they perform the operation.

When I came to, I was in intensive care. My torso was wrapped in bandages, and there was an IV stuck in my arm to feed me intravenously.

A doctor looked in on me and said, “Hiya, Rodney, how ya doin’? Don’t worry, we’ll have you walking in no time.”

He was right. I got the bill. I had to sell my car.

I mean, I’m not a kid anymore. I could go tomorrow. And I hope I go tomorrow. I haven’t gone today yet.

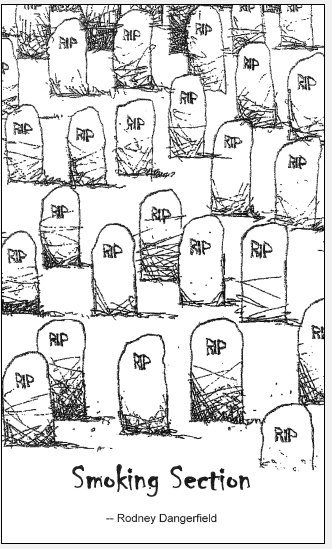

People often say, “It’s a miracle I’m alive.” And for me, they may be right. I was a heavy smoker for over fifty years. Never could stop. I used to walk around with three different packs of cigarettes in my pockets—filters, non-filters, and menthols. Sometimes I’d quit for a whole day. Then I’d give myself a reward—a cigarette.

That’s how I ended up going to the Pritikin Longevity Center in Santa Monica in 1982. It’s no longer there, but it was a highly recommended place where you could lose weight and stop smoking. So I thought, I’ll check in there for a month. I’ll take care of myself—which I did.

One morning, I ran into the head man, Nathan Pritikin, a great guy who was really down-to-earth.

I said, “Dr. Pritikin, nice to see you.”

He said, “Rodney, how’s your cholesterol?”

I thought, Wow, he gets right to it.

“Getting better, Doc,” I said. “But tell me something. You say don’t eat lobster because it’s all cholesterol. But if lobsters are all cholesterol, how come they live a hundred years?”

Nathan had a sense of humor. He said, “They don’t smoke, they don’t drink, and they watch what they eat.”

I said, “How about sex?”

He said, “No thanks. I don’t know you well enough.”

After a month in that place, I felt like a tiger.

After I left Pritikin, I didn’t smoke for three years. It gave me a chance to clean out my chest. It made my lungs fresh. Then one night I got drunk, and I had a cigarette.

After that, I was back smoking again. I smoked even after I had my aneurysm operation, right up until my double bypass. By then I knew it meant my life. So I finally stopped.

I haven’t smoked now in over three years. After my last bypass operation, I was all cleaned up, and I’d be a fool to start stuffing my lungs up all over again with cigarette smoke.

I never thought I could quit, but I did. Now when the urges come, when I think I can’t make it, I just remind myself that nobody ever died from not smoking.

What a doctor I’ve got—he’s really mixed up. Last week, he grabbed my knee and told me to cough. Then he hit me in the balls with a hammer.

I got three lucky breaks that summer I spent at Pritikin. I lost weight, I stopped smoking, and I met my wife, Joan Child. She owned a flower shop in Santa Monica. One day I stopped by to smell the roses. And I stopped by again the next day. And the next day. And the next…

We started dating, which was tough because I wasn’t in L.A. much once I got out of Pritikin. At that time I was doing dates all over the country and in Canada. Luckily, we stayed at it, though; we dated for ten years.

One night, when Joan was closing up her store, she said, “I know a great place to get a bite.”

I went back to visit all my old schoolteachers. I only had to make one stop, the cemetery.

Courtesy of the collection of Rodney Dangerfield.

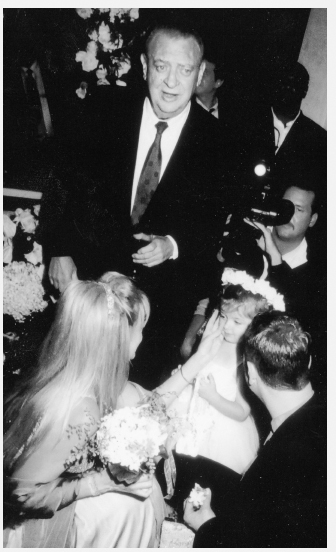

Me and my beautiful wife, Joan, on our wedding day. Joan is a Mormon, so next week, I’m marrying her sister, too.

Courtesy of the collection of Rodney Dangerfield.

I said, “Let’s go. But I need to take my car, too. I have to get up early tomorrow, so from the restaurant, I’ll go right back to Pritikin.”

“You’ll never find this restaurant,” she said. “Follow me.”

We took off in two cars. I was right behind her, but I had to drive fast to keep up. Next thing I knew, there was a police car behind me, lights flashing, bullhorn screeching, “Pull over!”

But I couldn’t. I knew that if I pulled over I’d lose her, and I didn’t know where we were going, so I hit the gas—and so did the cops. So now I was following Joan, and the cops were following me, lights still flashing.

When Joan finally stopped, the cops pulled up with their sirens wailing, bullhorns, the whole thing. I thought they were going to drag me out of my car and club me to death, but they were cool. When I explained the situation, they started to kid around with us, they were all right. Then they said they wanted my autograph—on a ticket.

People think I get plenty of girls. I go to drive-in movies and do push-ups in the backseat of my car.

My neighbors complained when I tied up traffic to have my new hot tub flown in. I didn’t see what the big deal was—it’s not like I was naked in it.

Courtesy of the collection of Rodney Dangerfield.

I moved to L.A. in 1990, and Joan and I finally got married on December 26, 1993. It wasn’t a big, dramatic thing—we just decided to do it. We flew up to Vegas, got married, then I played some craps and we flew home that night.

Besides going into show business and opening Dangerfield’s, this was another time people told me I was nuts. I married Joan with no prenuptial agreement. They thought I was making a big mistake. We are now married over ten years. It looks like “the mistake” worked out.

I learned in life, you can never say never. After my first marriage, I said I’d never get married again. Here I am married again, and this time it is the way it should be. Joan and I get along great. Thanks to Joan, I am in love, and I’m loving it.

I still have my bouts with depression, but I work through them. The worst depression I had was when I was in my seventies. It was a bad one. For two years, I couldn’t function. Finally I snapped out of it and started working again.

When we got married, the first thing my wife did was put everything under both names—hers and her mother’s.

In 2000, I had a double bypass, which is a technical term for: they cut my chest in half with an electric saw. It still hurts when I think about it.

When the operation was over and they wheeled me out, Joan was waiting for me in the cardiac intensive care unit. She later told me I had tubes stuck in me in every imaginable place, which reminds me of something my friend Joe Ancis said: “When you come to the end, you have a pipe in your nose, a pipe in your mouth, a pipe in your chest, arm, and neck. For the finish, we all turn Scottish.”

Later that night, when they took the tube out of my mouth, I could finally talk. I looked at my wife, and all I could say was, “Pain.”

Joan went to the nurse and said, “Look, he’s in a lot of pain. What can you do for him?” So they gave me something. Within five seconds the pain was gone and I was smiling. It was fantastic.

I asked Joan to find out what it was that they had given me. She told me it was Dilaudid—synthetic heroin—and boy, I can see how people get hooked on the real stuff.

I tell you, with my doctor, I don’t get no respect. I told him I’d swallowed a bottle of sleeping pills. He told me to have a few drinks and get some rest.

I was lucky I made it through all my surgeries. Many aren’t so lucky. Hospitals now admit that 120,000 patients a year die because of their mistakes. (It’s probably much more than that, but that’s all they will admit to.) That comes to more than 300 people a day who die by mistake. When you read things in the paper like He died after complications from heart surgery, that’s a lot of BS. They probably accidentally killed him.

You see a doctor. He looks so mature. His hair is neatly combed. His pants are perfectly pressed. In his pocket he has two pens. He’s smart. He knows that if one don’t work, he’s got another one. It’s hard to imagine that an hour from now there’s a chance he’ll be killing someone.

I’ve experienced plenty of hospital mistakes. Most of the nurses who brought me my pills made errors. Many times Joan stayed with me overnight in the hospital just to check on the pills—and they were usually wrong.

My doctor was giving me a complete physical, so he said, “I want a urine sample, a stool sample, and a semen sample.” So I left my underwear and I went home.

The doctors aren’t the only ones who don’t always prescribe the proper medication. I can do that for myself. I was in St. John’s Hospital recently. I forget exactly what was wrong, but I wasn’t feeling too good, so I went down there to get an EKG and a checkup, and it was a drag. I ended up in intensive care.

I was really bored, waiting around for hours, so I thought, Hey, there aren’t too many people here, and it’s dark. I’ll light up a joint. Nobody’ll notice, and I’ll feel okay.

The smoke from the joint went right down the hallway—a breeze or the air-conditioning must have caught it or something—and everybody could smell it. Two minutes later, a security guard came over.

I got lucky, though. He was a nice guy. I told him, “My wife won’t let me smoke at home, so I decided to come over here.”

You know you’re getting old when your insurance company sends you a half a calendar.