efore he was the subject of an off-Broadway play*, before he played himself in Woody Allen’s Annie Hall, before he gave the world eyes and ears for what it is to have eyes and ears in Understanding Media, Marshall McLuhan was a professor of English who loved James Joyce, hated television, denounced “Dagwood,” and explained all three. Even though he is the hero of a new generation of cybernauts and Information Highway trekkies, if McLuhan were alive today, he would probably refuse to have an e-mail address!

efore he was the subject of an off-Broadway play*, before he played himself in Woody Allen’s Annie Hall, before he gave the world eyes and ears for what it is to have eyes and ears in Understanding Media, Marshall McLuhan was a professor of English who loved James Joyce, hated television, denounced “Dagwood,” and explained all three. Even though he is the hero of a new generation of cybernauts and Information Highway trekkies, if McLuhan were alive today, he would probably refuse to have an e-mail address!

* “The Medium” played to enthusiastic audiences at the New York Theater Workshop in 1993-94 and earned actor Tom Nelis an Obie award for his portrayal of McLuhan.

arshall McLuhan was born in 1911 in Edmonton, Canada, and raised in Winnipeg. He received his B.A. (1933) and M.A. (1934) from the University of Manitoba, earning a second B.A. in English literature from Cambridge University (England) in 1936. The lessons McLuhan learned during those early days at Cambridge formed the base for his later studies of media. Which brings us to the question: How did a Canadian professor of English become a world-renowned, avant-garde media guru?

arshall McLuhan was born in 1911 in Edmonton, Canada, and raised in Winnipeg. He received his B.A. (1933) and M.A. (1934) from the University of Manitoba, earning a second B.A. in English literature from Cambridge University (England) in 1936. The lessons McLuhan learned during those early days at Cambridge formed the base for his later studies of media. Which brings us to the question: How did a Canadian professor of English become a world-renowned, avant-garde media guru?

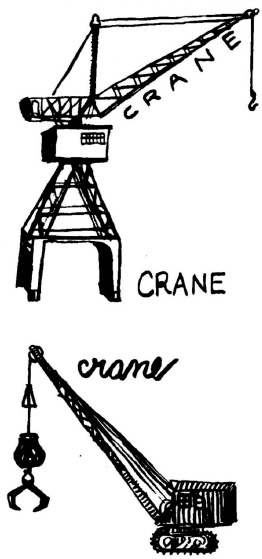

y extending lessons on language learned from one of his own teachers—namely I. A. Richards, whose lectures McLuhan attended at Cambridge University in the 1930s. Richards pioneered an approach to literary criticism that focused on the meaning of words and how they are used. He deplored the “proper meaning superstition,” the belief that word-meanings are fixed and independent of their use, and he forcefully illustrated the power of words to control thought.

y extending lessons on language learned from one of his own teachers—namely I. A. Richards, whose lectures McLuhan attended at Cambridge University in the 1930s. Richards pioneered an approach to literary criticism that focused on the meaning of words and how they are used. He deplored the “proper meaning superstition,” the belief that word-meanings are fixed and independent of their use, and he forcefully illustrated the power of words to control thought.

ichards argued that thought should bring words under its control by determining meaning from context. This was the key idea of the book he wrote with C. K. Ogden, called The Meaning of Meaning. The idea stayed with McLuhan right through to his later writings.

ichards argued that thought should bring words under its control by determining meaning from context. This was the key idea of the book he wrote with C. K. Ogden, called The Meaning of Meaning. The idea stayed with McLuhan right through to his later writings.

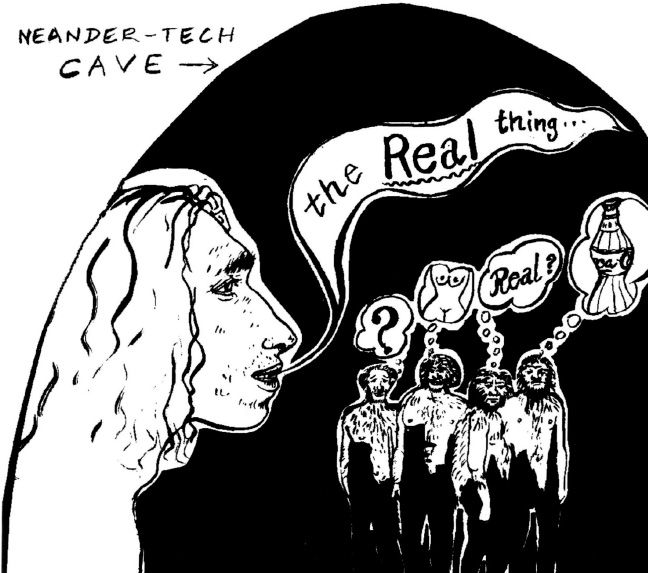

“All media are active metaphors in their power to translate experience into new forms. The spoken word was the first technology by which man was able to let go of his environment in order to grasp it in a new way.” (Understanding Media, p. 57)

“Nothing has its meaning alone. Every figure [consciously noted element of a structure or situation] must have its ground or environment [the rest of the structure or situation which is not noticed]. A single word, divorced from its linguistic ground would be useless. A note in isolation is not music. Consciousness is corporate action involving all the senses (Latin sensus communis or ‘common sense’ is the translation of all the senses into each other). The ‘meaning of meaning’ is relationship”.

(Take Today, p.30)

ichards viewed any act of understanding or acquiring knowledge as a matter of interpreting and reinterpreting—a process he called “translation.” A key chapter in McLuhan’s Understanding Media, titled “Media as Translators,” not only picks up this theme but links it to Richards’s observations on the multiplicity of sensory channels:

ichards viewed any act of understanding or acquiring knowledge as a matter of interpreting and reinterpreting—a process he called “translation.” A key chapter in McLuhan’s Understanding Media, titled “Media as Translators,” not only picks up this theme but links it to Richards’s observations on the multiplicity of sensory channels:

f course, there were many sources of influence on McLuhan’s thought besides I. A. Richards, but few that came so early in his career or endured so long. Beyond Richards, the sources of influence on McLuhan were many and varied:

f course, there were many sources of influence on McLuhan’s thought besides I. A. Richards, but few that came so early in his career or endured so long. Beyond Richards, the sources of influence on McLuhan were many and varied:

the French symbolist poets of the late 19th century

the French symbolist poets of the late 19th century

the Irish writer James Joyce

the Irish writer James Joyce

the English painter and writer Wyndham Lewis

the English painter and writer Wyndham Lewis

Anglo-American poet and critic T. S. Eliot

Anglo-American poet and critic T. S. Eliot

American poet Ezra Pound

American poet Ezra Pound

literary critic F. R. Leavis

literary critic F. R. Leavis

Canadian economic historian Harold Innis.

Canadian economic historian Harold Innis.

The richness of McLuhan’s thought comes from the unique meshing of all these sources and the “feedforward” (another idea from I. A. Richards) he developed as a method for understanding popular culture and media.

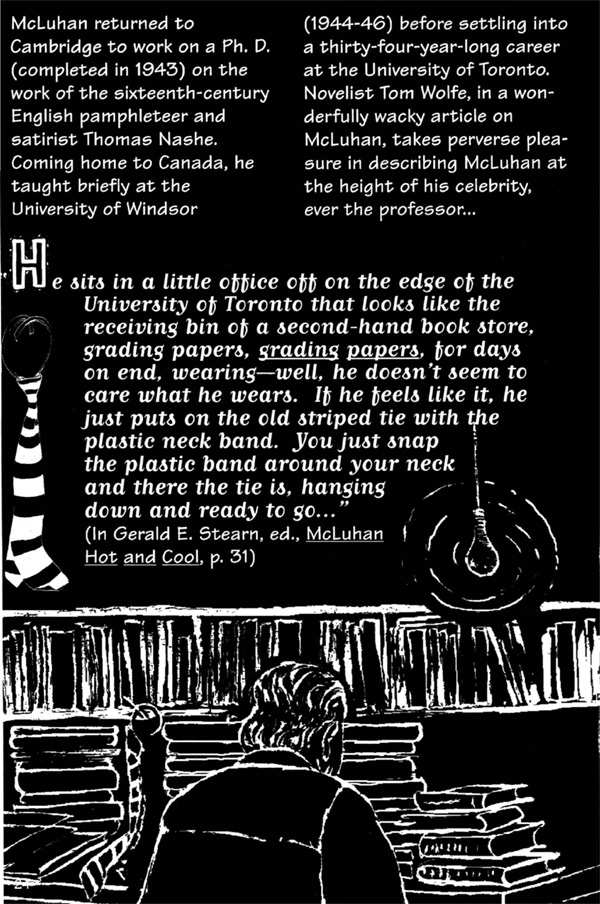

uring his first stint at Cambridge University, McLuhan converted to Roman Catholicism, under the influence of such writers as G. K. Chesterton, and was received into the church in Madison, Wisconsin in 1937. After one year of teaching at the University of Wisconsin, he moved to St. Louis University Though just twenty-five years old when he began his teaching career, McLuhan was shocked to find a “generation gap” between himself and his students. Feeling an urgent need to bridge this gap, he set out to understand what he suspected as its cause—the effect of mass media on American culture. He was on his way to writing his first book—The Mechanical Bride (1951).

uring his first stint at Cambridge University, McLuhan converted to Roman Catholicism, under the influence of such writers as G. K. Chesterton, and was received into the church in Madison, Wisconsin in 1937. After one year of teaching at the University of Wisconsin, he moved to St. Louis University Though just twenty-five years old when he began his teaching career, McLuhan was shocked to find a “generation gap” between himself and his students. Feeling an urgent need to bridge this gap, he set out to understand what he suspected as its cause—the effect of mass media on American culture. He was on his way to writing his first book—The Mechanical Bride (1951).