n this book McLuhan notes that his objective is not to offer a static theory of human communication but to probe the effects of anything humans use in dealing with the world. “To understand media,” he wrote,

n this book McLuhan notes that his objective is not to offer a static theory of human communication but to probe the effects of anything humans use in dealing with the world. “To understand media,” he wrote,

If that approach makes academics nervous, it is certainly one that every artist is comfortable with.

McLuhan’s method? It’s all in the fingers:

“Most of my work in the media is like that of a safecracker. In the beginning I don’t know what’s inside. I just set myself down in front of the problem and begin to work. I grope, I probe, I listen, I test—until the tumblers fall and I’m in.” (From the Introduction to Gerald Stearn’s McLuhan Hot and Cool)

cLuhan called his way of thinking and investigating “probes” (you know, like the things we shot off into outer space in the ‘60s and ‘70s?) Throughout his writings he relies on such probes to gain insight into media and their effects.

cLuhan called his way of thinking and investigating “probes” (you know, like the things we shot off into outer space in the ‘60s and ‘70s?) Throughout his writings he relies on such probes to gain insight into media and their effects.

To many academics of McLuhan’s era, his concept of probes remains one of the most irritating aspects of his method. Faith in the power of the probe allowed McLuhan to take stabs at a wide range of topics, from the serious to the ridiculous, without necessarily committing himself to conclusions or testing his hypotheses scientifically—a habit that infuriated his critics and detractors.

TWO “PROBING” QUESTIONS

uring McLuhan’s heyday, people argued for hours about what he really meant. In Woody Allen’s charming film “Annie Hall,” Woody and Diane Keaton were standing in a movie line, when a nerd ahead of them started spouting off about what McLuhan really meant, McLuhan—who just happened to be standing nearby—began to explain himself. (Actually, to misquote himself.) One of McLuhan’s favorite retorts to hecklers was “You think my fallacy is all wrong?” But in the film, McLuhan’s “probing” question was changed into a statement: “You mean my fallacy is all wrong.”

uring McLuhan’s heyday, people argued for hours about what he really meant. In Woody Allen’s charming film “Annie Hall,” Woody and Diane Keaton were standing in a movie line, when a nerd ahead of them started spouting off about what McLuhan really meant, McLuhan—who just happened to be standing nearby—began to explain himself. (Actually, to misquote himself.) One of McLuhan’s favorite retorts to hecklers was “You think my fallacy is all wrong?” But in the film, McLuhan’s “probing” question was changed into a statement: “You mean my fallacy is all wrong.”

QUESTION: Why do you think McLuhan was displeased with the change he was asked to make in the form of this quip in his cameo as himself in “Annie Hall”?

Answer: In the film, McLuhan’s question is turned into a statement and is no longer a disabling tactic against an aggressive opponent. As a question, it forces an opponent to stop and think, because it is unexpected—a probe! As a statement, it loses this force and undermines the authority that McLuhan represents in the scene.

Canadian artist Alan Flint shapes words out of wood, brick, cardboard, plastic, plaster, etc. In a field he dug out the word WOUND in giant letters to symbolize the effect of human systems on the earth.

QUESTION: Is this an example of the medium being the message?

Answer: Yes. For McLuhan, language is technology and words are artifacts. Flint’s WOUND is part of the technology of language executed in a way that reminds us that the technology of digging wounds the earth. Flint weds his words to different technologies but in every case reminds us of the link between the word’s meaning and the technology used in spelling it out. He also reminds us that words are artifacts and forces us to reflect on the medium and the message by forcing them together in new ways. (This is an example of an artist making probes out of clichés, a process that is explained in detail on page 107.)

And, boy, did he ever! Wired notes that while McLuhan was a political conservative and a devout Catholic, “his pronouncements on current events always add an element of loony dispassion and professional absent-mindedness” (January 1996, p. 125) McLuhan was, to say the least, a prolific thinker. The following are just a few of his more clever responses to pop culture phenomena and whatever else snagged the attention of his rapid-fire mind. (We’re not quoting him here—just summing up his takes on the subject-of-the-day.)

Time Magazine? Intellectual Pablum spooned out with all the cues for the right reaction.

Reader’s Digest? It stimulates curiosity with its endless emphasis on making the impossible happen, cluttering the mind (a sort of cerebral indigestion ) of readers who might otherwise feast on reading material of a greater intellectual challenge.

The twentieth century? The age that moved beyond invention to studying process (whether in literature, painting, or science) in isolation from product.

King Lear? The play is a model for the transition from the integrated world of roles to the fragmented world of jobs.

Schizophren? Perhaps an inevitable consequence of the sensory imbalance created by literacy.

MAD Magazine? mocks the hot media by replaying them cool

Renaissance Italy Like a Hollywood assemblage of sets of antiquity.

Panic about automation? It is a reaction that perpetuates the dominant nineteenth century model of mechanical standaradization and fragmentation of work.

Alice in Wonderland? Dislocated the concepts of time and space as uniform and continuous—concepts that had prevailed since the Renaissance.

The city? A collective extension of our skins.

Hitler? His demagoguery was ideally suited to radio, but if television had already been widespread in his day, he would have disappeared quickly.

Football? It is displacing baseball because it is nonpositional, decentralized, and corporate—qualities of the electronic age.

The clock? It is a machine that turns out the uniform products of seconds, minutes and hours on an assembly-line pattern, separating time from the rhythm of human experience.

Earth-orbiting satellites? They put an end to nature by creating a new environment for the earth.

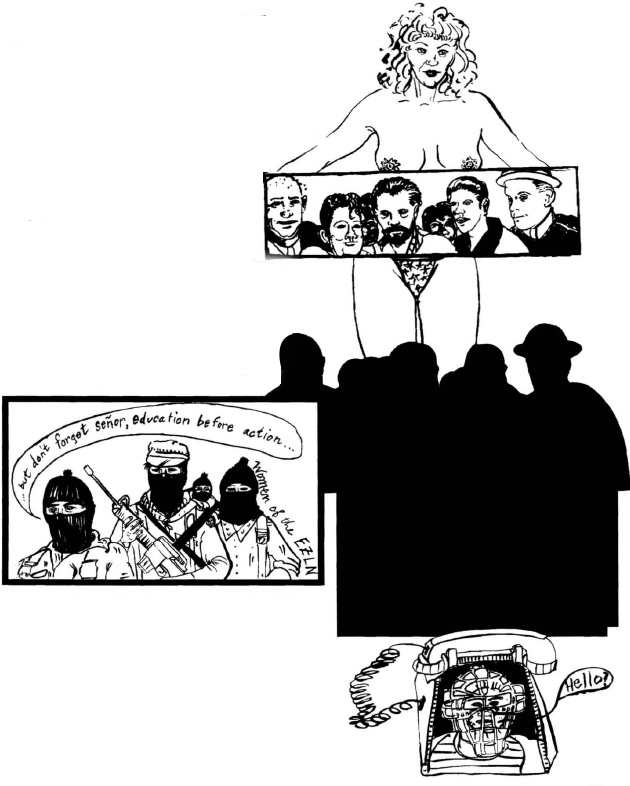

Strippers? They wear their audience when they take off their clothes. The audience creates a new environment (new clothing) for the stripper.

Violence? The creativity and the search for identity of the oppressed.

The car following the horse? The car displaced the horse as transportation, but the horse made a comeback in the domain of entertainment and sport. Now that the car has been displaced by the jet, the car is taking on a new role as art and costume.

The Journal of Irreproducible Results? It satirizes the specialist knowledge that belongs to the Gutenberg age.

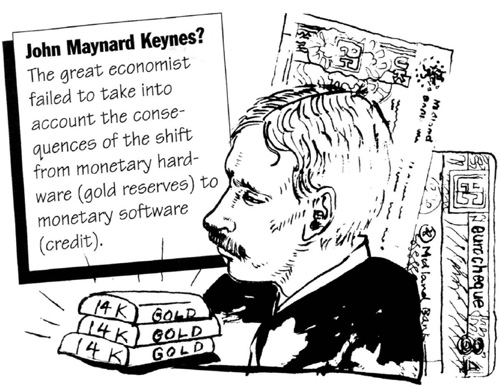

Karl Marx? The founder of communism failed to take into account the service environments that arise from the production of goods.

The internal combustion engine? It was the engine of change that integrated the society of whites and blacks in the U.S. South when private cars and trucks became available.

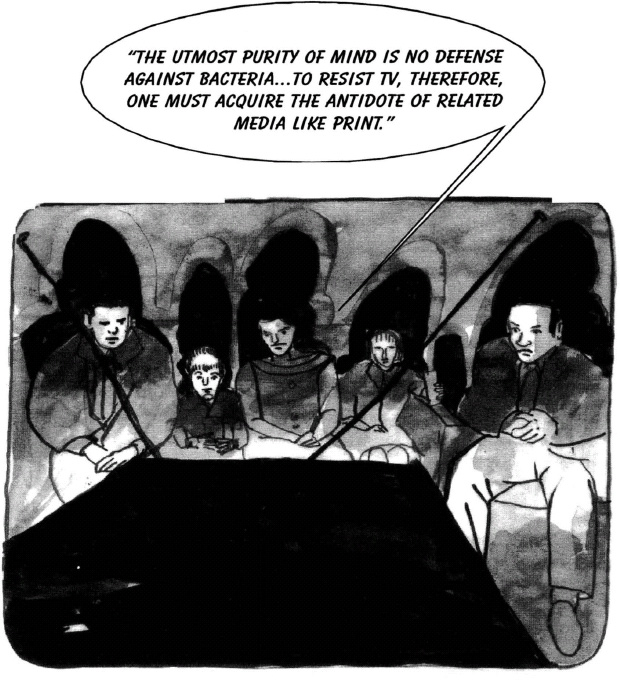

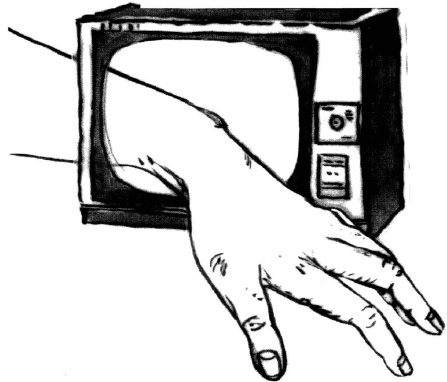

hen McLuhan first came to the attention of the general public in the 1960s, many assumed that he was promoting the end of book culture and embracing the age of television. In fact, he was cautioning that the then-new medium of television had enormous power. Publicly, he called it “the timid giant” and urged awareness of that power.

hen McLuhan first came to the attention of the general public in the 1960s, many assumed that he was promoting the end of book culture and embracing the age of television. In fact, he was cautioning that the then-new medium of television had enormous power. Publicly, he called it “the timid giant” and urged awareness of that power.

Lewis Lapham says that McLuhan’s thinking about media begins with two premises: on the one hand, he notes, McLuhan argued that “we become what we behold;” on the other, he stated that “we shape our tools, and thereafter our tools shape us.” McLuhan saw media as make-happen rather than make-aware agents, as systems more similar in nature to roads and canals than to objects of art or models of behavior.

Most of us think of media (one “medium;” two or more “media”) as sources that bring us news or information—namely the press, radio, and television. But McLuhan had his own ingeniously original definition of media. To him, a medium—while it may often be a new technology—is any extension of our bodies, minds, or beings ...

-clothing is an extension of skin-

-housing is an extension of the body’s heat-control mechanism-

-the stirrup, the bicycle, and the car extend the human foot-

-the computer extends our central nervous system-

y saying “the medium is the message” McLuhan forces us to re-examine what we understand by both “medium” and “message.” We have just seen how he stretched the meaning of “medium” beyond our usual understanding of the word. He does this for “message” too. If we define “message” simply as the idea of “content” or “information,” McLuhan believes, we miss one of the most important features of media: their power to change the course and functioning of human relations and activities. So, McLuhan redefines the “message” of a medium as any change in scale, pace, or pattern that a medium causes in societies or cultures.

y saying “the medium is the message” McLuhan forces us to re-examine what we understand by both “medium” and “message.” We have just seen how he stretched the meaning of “medium” beyond our usual understanding of the word. He does this for “message” too. If we define “message” simply as the idea of “content” or “information,” McLuhan believes, we miss one of the most important features of media: their power to change the course and functioning of human relations and activities. So, McLuhan redefines the “message” of a medium as any change in scale, pace, or pattern that a medium causes in societies or cultures.

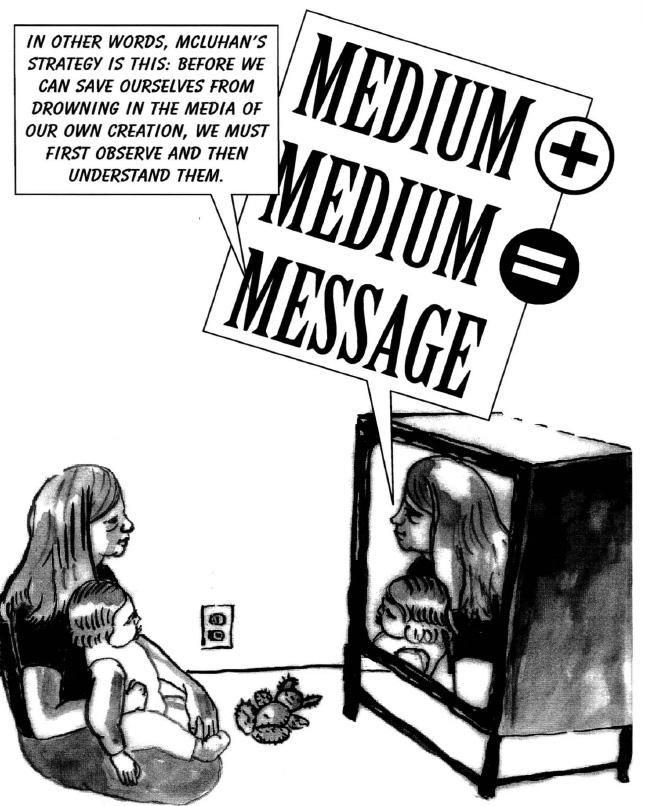

nother reason for this new definition is that “content” turns out to be an illusion, or at least a mask for how media interact. They work in pairs; one medium “contains” another (and that one can contain another, and so on). The telegraph, for example, contains the printed word, which contains writing, which contains speech. So, the contained medium becomes the message of the containing one!

nother reason for this new definition is that “content” turns out to be an illusion, or at least a mask for how media interact. They work in pairs; one medium “contains” another (and that one can contain another, and so on). The telegraph, for example, contains the printed word, which contains writing, which contains speech. So, the contained medium becomes the message of the containing one!

Now because we don’t usually notice this kind of interaction of media, and because the effects of it are so powerful on us, any message, in the ORDINARY sense of “content” or “information” is far less important than the medium itself.

I. Speech

Speech is the content of writing, but what is the content of speech? McLuhan’s answer: Speech contains thought, but here the chain of media ends. Thought is non-verbal and pure process.

A second pure process or message-free medium is:

II. The Electric Light

Why does it stand alone?

McLuhan’s answer: Artificial light permits activities that could not be conducted in the dark. These activities can be thought of as the “content” of the light, but light itself contains no other medium.

Whether message-containing or message-free, all of the above examples reinforce McLuhan’s point that media change the form of human relations and activities. They also reinforce his point about the importance of studying media:

cLuhan saw that media are powerful agents of change that affect how we experience the world, interact with each other, and use our physical senses—the same senses that media themselves extend. He stressed that media must be studied for their effects, not their content, because their interaction obscures these effects and deprives us of the power to keep media under our control.

cLuhan saw that media are powerful agents of change that affect how we experience the world, interact with each other, and use our physical senses—the same senses that media themselves extend. He stressed that media must be studied for their effects, not their content, because their interaction obscures these effects and deprives us of the power to keep media under our control.

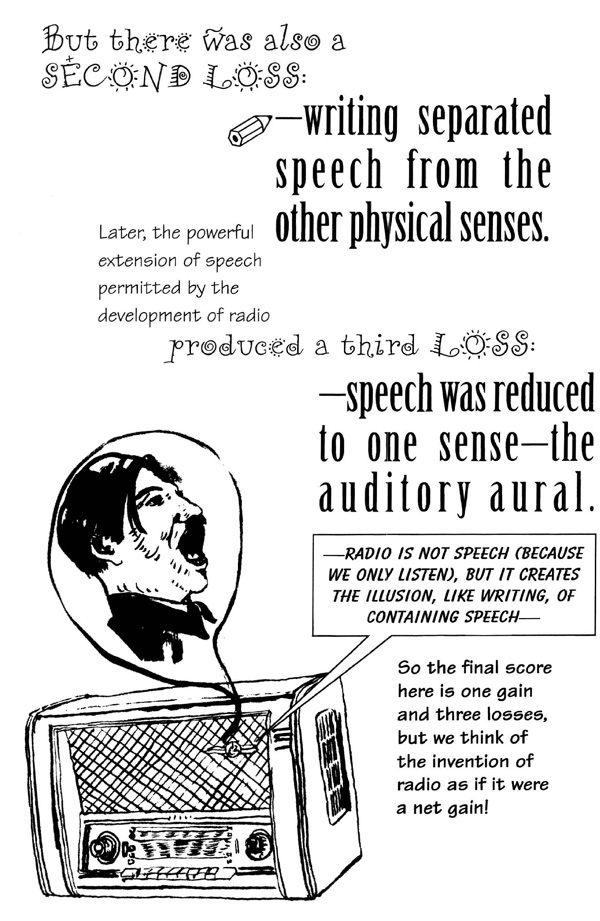

The technology of the age of acoustic space, the technology that later gave writing, print, and telegraph, was speech.

Transformed into writing, speech LOST the quality it had in the age of acoustic space.

It ACQUIRED a powerful visual bias, with effects spilling over into social and cultural organization—and these are still with us today in the electronic age.

ince he was delivering his messages in The Gutenberg Galaxy and Understanding Media via a medium (the printed page) outmoded by the electronic age, McLuhan adopted a style called “mosaic writing” that attempts to mimic the disconnected, low-definition coolness of television. A 1967 Newsweek feature article on McLuhan gave his approach mixed reviews. The article notes that McLuhan’s writing is “deliberate, repetitious, confused and dogmatic.” Another Newsweek piece gave a somewhat more favorable but still critical review:

ince he was delivering his messages in The Gutenberg Galaxy and Understanding Media via a medium (the printed page) outmoded by the electronic age, McLuhan adopted a style called “mosaic writing” that attempts to mimic the disconnected, low-definition coolness of television. A 1967 Newsweek feature article on McLuhan gave his approach mixed reviews. The article notes that McLuhan’s writing is “deliberate, repetitious, confused and dogmatic.” Another Newsweek piece gave a somewhat more favorable but still critical review:

n Understanding Media, McLuhan uses the Greek myth of Narcissus as a dualpurpose metaphor for the failure to understand media as extensions of the human body and the failure to perceive the message (new environments) created by media (technology):

n Understanding Media, McLuhan uses the Greek myth of Narcissus as a dualpurpose metaphor for the failure to understand media as extensions of the human body and the failure to perceive the message (new environments) created by media (technology):

[Narcissus] saw his image reflected in a fountain, and became enamored of it, thinking it to be the nymph of the place. His fruitless attempts to approach this beautiful object so provoked him, that he grew desperate and killed himself.

-Lemprière’ Classical Dictionary

McLuhan begins by pointing out the common misrepresentation which claims that Narcissus had fallen in love with himself. Not so, sayeth our Marshall. It was Narcissus’s inability to recognize his image that brought him to grief! The low-tech medium of water and the reflections if allows to form were the culprits! if McLuhan had been around in Narcissus’s day, the poor guy would have understood that a little experimenting might have given him control of the medium and allowed him to recognize his own reflection. But, the story goes, Narcissus succumbed to the numbing effect of the sort that McLuhan says all technologies produce, if the user does not scrutinize their operation closely: technologies (new media) create new environments, new environments create pain, and the nervous system shuts down to block the pain. Indeed, McLuhan points out that the name Narcissus comes from the Greek word narcosis, meaning numbness. Narcissus, narcosis. In poor Narcissus’s case, the results were fatal.

To McLuhan, the story of Narcissus illustrates humankind’s obsessive fascination with new extensions of the body (media), but it also shows how these extensions are inseparable from what McLuhan calls...

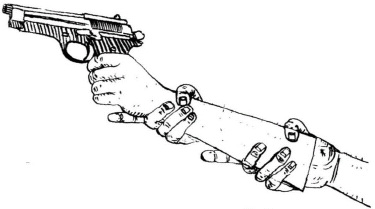

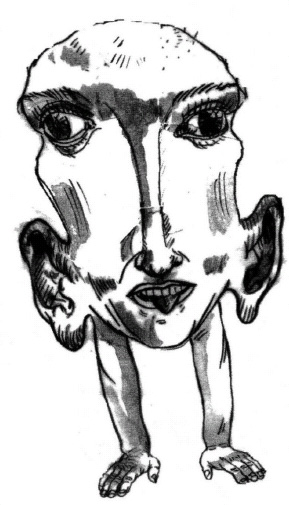

ake the wheel (as one of McLuhan’s examples, that is). As a new technology, the wheel took the pressure of carrying loads off the human foot, which it extends. But it also created new pressure by separating or isolating the function of the foot from other body movements. Whether you are pedalling a bicycle or speeding down the freeway in your car, your foot is performing such a specialized task that you cannot, at that moment, allow it to perform its basic function of walking. So, although the medium has given you the power to move much more quickly, you are, in another sense, immobilized, paralyzed. In this way, our technologies both extend AND amputate.

ake the wheel (as one of McLuhan’s examples, that is). As a new technology, the wheel took the pressure of carrying loads off the human foot, which it extends. But it also created new pressure by separating or isolating the function of the foot from other body movements. Whether you are pedalling a bicycle or speeding down the freeway in your car, your foot is performing such a specialized task that you cannot, at that moment, allow it to perform its basic function of walking. So, although the medium has given you the power to move much more quickly, you are, in another sense, immobilized, paralyzed. In this way, our technologies both extend AND amputate.

Amplification becomes amputation. Then the central nervous system reacts to the pressure and disorientation of the amputation by blocking perception.

McLuhan used this example to claim that the transition from mechanical to electronic media led to a relentless acceleration—a virtual explosion—of all human activity. But what happens, when media go too far? His answer was simple: Like the overextended highway that turns cities into highways and highways into cities, the technological explosion reverses into an implosion. The expansionist pattern associated with the older technology conflicts with the contracting energies of the new one.

emember what McLuhan said about hot and cool media? Well, he also claimed that the vast creative potential unleashed by new media can lead to overheating—sometimes with destructive results. In Understanding Media, McLuhan offers examples of overheated media and the reversals they cause. For example, he notes that the industrial Western societies of the nineteenth century placed extreme emphasis on fragmented procedures in the work place.

emember what McLuhan said about hot and cool media? Well, he also claimed that the vast creative potential unleashed by new media can lead to overheating—sometimes with destructive results. In Understanding Media, McLuhan offers examples of overheated media and the reversals they cause. For example, he notes that the industrial Western societies of the nineteenth century placed extreme emphasis on fragmented procedures in the work place.

But, with electrification, both the commercial and social world of industrialized societies began to put new emphasis on unified and unifying forms of organization (corporations, monopolies, clubs, societies). Musings such as these led McLuhan to conclude that electronic technology created a “global village” where knowledge must be synthesized instead of being splintered into specialties. (More on the g.v. later!)

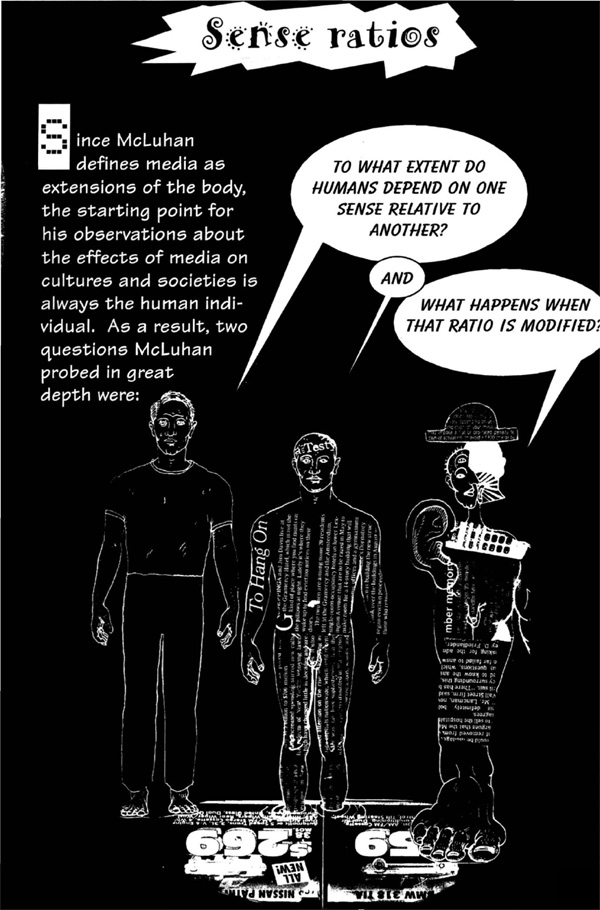

cLuhan argued that the introduction of new media alters what he called our sense ratio, or the relationship among the five physical senses. He further argued that the senses may be ranked in order of how complex the perceptions are that we get through them.

cLuhan argued that the introduction of new media alters what he called our sense ratio, or the relationship among the five physical senses. He further argued that the senses may be ranked in order of how complex the perceptions are that we get through them.

Sight comes first, he claimed, because the eye is a specialized organ that permits perceptions of enormous complexity. Then come hearing, touch, smell and taste.

Reading down the list, we move to less specialized senses. By contrast with the enormous power of the eye and the distances from which it can receive a stimulus, the tongue is capable of distinguishing only sweet, sour, bitter, and salt, and only in direct contact with the substance providing the stimulus.

Because any modifications to our sense ratio inevitably involve a psychological dimension, McLuhan cautioned against any rigid separation of the physical from the psychological—perhaps in all analysis, but especially for an understanding of media and their effects.

McLuhan alleged that the resulting intensification of the visual sense—and reliance on it—in the communication process swamped hearing so forcefully that the effect spilled over from language and communication to reshape literate society’s conception of space. Here are further examples, where McLuhan stresses sense ratios and the effects of altering them:

In dentistry, a device called audiac was developed. It consists of headphones bombarding the patient with enough noise to block pain from the dentist’s drill.

In Hollywood, the addition of sound to silent pictures impoverished and gradually eliminated the role of mime, with its tactillity and kinesthesis.

cLuhan believes that when the microphone was introduced into Catholic churches it brought about the demystification of things spiritual for many believers. The introduction of a new technology started a chain reaction: First the Latin mass, as a “cool” medium, was rendered obsolete, because it is unsuited to amplification. (A hot medium can be overheated or overextended, and this intensification can make the medium more effective, but a cool one, when overheated, becomes less effective.) Next came the obsolescence of traditional church architecture, the decline in the use of incense (knocking out the sense of smell) and the disappearance of the rosary (eliminating the tactile sense).

cLuhan believes that when the microphone was introduced into Catholic churches it brought about the demystification of things spiritual for many believers. The introduction of a new technology started a chain reaction: First the Latin mass, as a “cool” medium, was rendered obsolete, because it is unsuited to amplification. (A hot medium can be overheated or overextended, and this intensification can make the medium more effective, but a cool one, when overheated, becomes less effective.) Next came the obsolescence of traditional church architecture, the decline in the use of incense (knocking out the sense of smell) and the disappearance of the rosary (eliminating the tactile sense).

What McLuhan calls the “audio backdrop” of Latin used to provide an invitation to intense participation through meditation as the priest said mass. This was replaced by the high-definition medium of the mass in the vernacular, required by and then intensified still further by the use of microphones and loudspeakers, but no longer requiring intense sensory or spiritual involvement. As for the cathedral architecture, with its shape and dimensions dictated for centuries by the acoustical requirements of a non-electronically amplified voice, it became as obsolete as Latin.

veryone knows that friction, caused by rubbing two items together, creates heat. Like friction, McLuhan claimed, combining media unleashes powerful forces, but neither the creation of such energy nor the experience of it brings about an awareness of what is happening. That’s because media mask each other when they interact.

veryone knows that friction, caused by rubbing two items together, creates heat. Like friction, McLuhan claimed, combining media unleashes powerful forces, but neither the creation of such energy nor the experience of it brings about an awareness of what is happening. That’s because media mask each other when they interact.

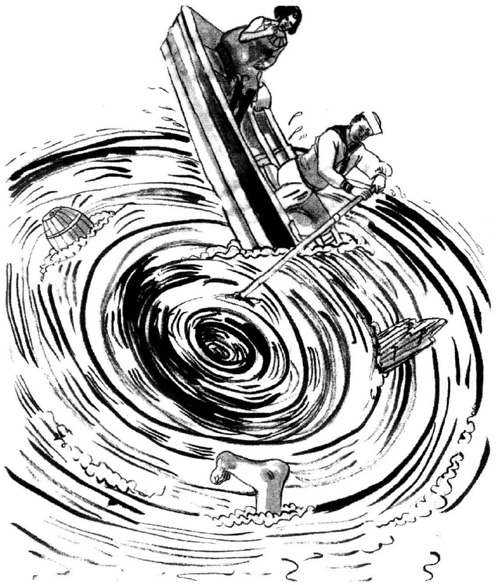

McLuhan is optimistic that media consciousness can be raised by following appropriate strategies. To illustrate, he turned to Edgar Allen Poe’s “A Descent into the Maelstrom.” In this story, a sailor rescues himself from the whirlpool engulfing him by calmly observing its effects on the various objects caught in the downward spiral. The sailor’s attitude of rational detachment allows him to find a means of escape and even intellectual amusement in the midst of the environment that threatens his life.

Media effects are just as inescapable as the whirlpool of the story, McLuhan contends, BUT detached analysis of their operation can bring freedom from their numbing effects.

Such analysis is never easier, says McLuhan, than when two media meet, yielding the equation:

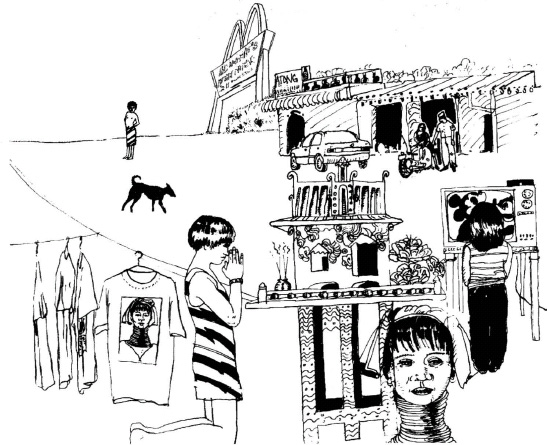

o drive home this point, McLuhan turns again to the example of electricity, but he also uses the metaphor of violent energy —the fission of the atomic bomb and the fusion of the hydrogen bomb—to speculate on the final outcome of these changes. It’s changes in cultures and societies that occupy McLuhan most fully (pre-literate, non-Western cultures are fragmented by the introduction of writing; visual, specialist, Western culture is retribalized by electricity), but he offers other examples:

o drive home this point, McLuhan turns again to the example of electricity, but he also uses the metaphor of violent energy —the fission of the atomic bomb and the fusion of the hydrogen bomb—to speculate on the final outcome of these changes. It’s changes in cultures and societies that occupy McLuhan most fully (pre-literate, non-Western cultures are fragmented by the introduction of writing; visual, specialist, Western culture is retribalized by electricity), but he offers other examples:

When the telegraph restructured the press medium, human interest stories, previously the preserve of the theater, were introduced into newspapers, causing the decline of theater.

When the telegraph restructured the press medium, human interest stories, previously the preserve of the theater, were introduced into newspapers, causing the decline of theater.

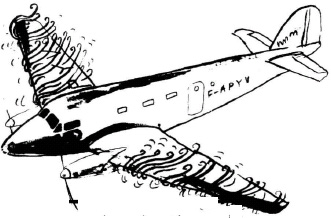

For just a moment before an airplane breaks the sound barrier, sound waves become visible on its wings. Then they disappear as the plane moves into the new environment beyond the speed of sound. It is a metaphor for the moment when the structure of a medium is revealed as it meets with another.

For just a moment before an airplane breaks the sound barrier, sound waves become visible on its wings. Then they disappear as the plane moves into the new environment beyond the speed of sound. It is a metaphor for the moment when the structure of a medium is revealed as it meets with another.

When media combine, McLuhan observes, they establish new ratios among themselves, just as they establish new ratios among the senses. For example,

When radio came along, it changed the way news stories were presented and the way film images were presented in talkies

When radio came along, it changed the way news stories were presented and the way film images were presented in talkies

then television came along and brought big changes in radio

then television came along and brought big changes in radio

In a nutshell:

—When media combine, both their form and use change—

—so do the scale, speed, and intensity of the human endeavors affected, as well as the ratios of senses involved—

—so do the environments where the media and their users are found—

IT'S A TRIPLE PLAY!! NEW MEDIA TO NEW SENSORY BALANCE TO NEW ENVIRONMENT!!

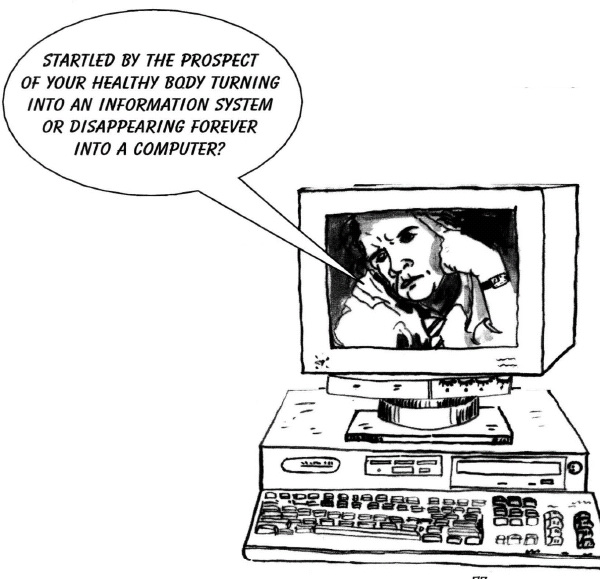

et’s test McLuhan’s ideas by taking an example of technology that was not available in his time. For instance:

et’s test McLuhan’s ideas by taking an example of technology that was not available in his time. For instance:

The optical Scanner

The optical scanner reads and reproduces texts or images with great speed and accuracy (especially in the case of images that otherwise would have to be created by free-hand reproduction). As a writing medium, it renders obsolete all the non-hybridized and non-electronic technologies that preceded it, from the quill to the typewriter, AND the hand that uses them. As a powerful visual technology, and because it is hybridized, the scanner reduces its users to proof-readers and document managers. So, the scanner is a hybrid extension of the eye and the hand.

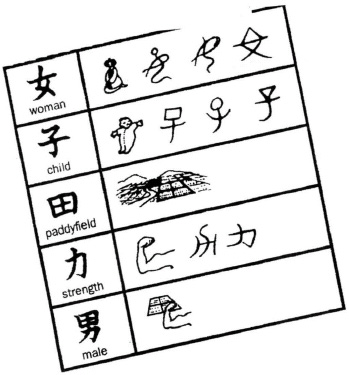

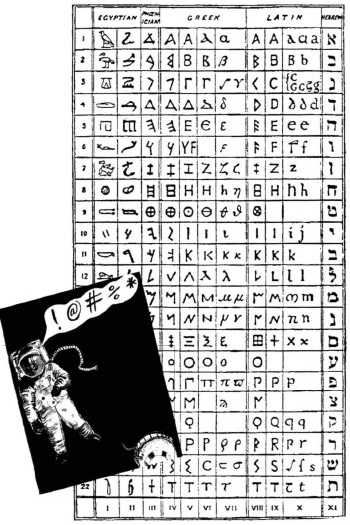

e write English in what is called a “phonetic” alphabet. The letters of our alphabet stand for sounds. A phonetic alphabet is a medium, as McLuhan defines medium (remember?—a medium is any extension of our bodies or minds).

e write English in what is called a “phonetic” alphabet. The letters of our alphabet stand for sounds. A phonetic alphabet is a medium, as McLuhan defines medium (remember?—a medium is any extension of our bodies or minds).

The phonetic alphabet is an extension of BOTH our bodies and our minds, because:

it turns the sounds of language that we make with our lungs and tongues and teeth and lips into visual markings—

it turns the sounds of language that we make with our lungs and tongues and teeth and lips into visual markings—

the sounds extend or “outer” ( =“utter”—a pun McLuhan loved) the thoughts in our minds.

the sounds extend or “outer” ( =“utter”—a pun McLuhan loved) the thoughts in our minds.

We’ve also got media working in pairs here again!!

So, the phonetic alphabet is a medium, because it’s an extension, BUT it’s also a medium in the basic sense of “something that goes between”—AND BRINGS TOGETHER. What does the alphabet go between and bring together? Answer: MEANING and SOUND.

If we compare, say, Chinese writing with the phonetic alphabet, there is no “go-between” for Chinese. The writing gives meanings, but it doesn’t show how to pronounce what is written.

If you are having trouble understanding this, think about symbols like

+ & -

There is nothing in the shapes of these symbols to show how they are pronounced, but there is in

plus and minus.

Imagine if EVERY written word in English was a symbol like

“+” instead of “plus”

“&” instead of “and”

“−” instead of “minus”

and then you’ve got an idea of how Chinese writing works.(I think I hear a reader going !@#%* Very non-phonetic. You ARE getting it!)

McLuhan understood that the EFFECTS of a phonetic alphabet are very different from those of non-phonetic writing and very powerful. He sees the invention of the phonetic alphabet as having set off a chain reaction that gave Western civilization everything from logic and linear space to nationalism and assembly lines.

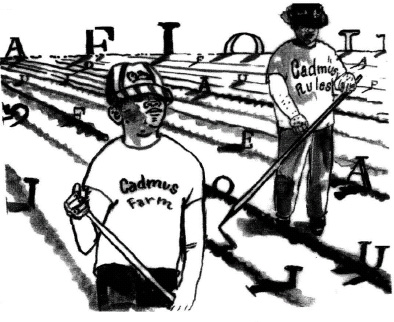

McLuhan finds a lesson on the power of media once again in Greek mythology. It was king Cadmus who planted dragon’s teeth from which an army sprang up. It was also Cadmus who introduced the phonetic alphabet (from Phoenicia) to Greece.

McLuhan interprets the dragon’s teeth as an older form of non-phonetic writing from which the much more powerful alphabet grew.

emember the immortal words of poet Robert Browning:

emember the immortal words of poet Robert Browning:

True to form, McLuhan turns these words on their head in probing media messages with a tongue-in-cheek phrase of his own:

If we take the “reach” and the “grasp” in McLuhan’s quip as mental rather than physical, the question contains its answer, just as McLuhan claims that media contain each other.

McLuhan saw it this way: In language, a metaphor is an extension of consciousness, a medium in the broad sense that is fundamental for McLuhan. When we look beyond language,

ALL media are active metaphors, or technologies for transforming human experience.

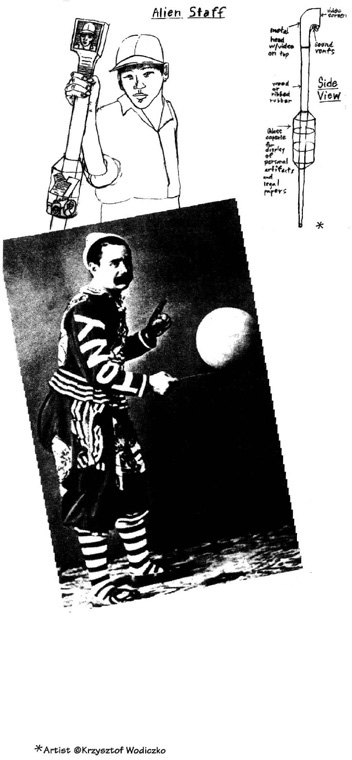

According to our Marshall, until electronic media became the dominant technology, the transformations of human experience were those of the human body mechanically extended. Now they are of human consciousness electronically extended. Activities previously performed only by electro-chemical energy in the human brain can now be performed by electromagnetic energy in the computer. The result: we—individuals, societies, nations, schools, businesses, citizens of the global village—are transformed into information systems. So powerful is the technology of the computer, McLuhan cautioned more than twenty years ago, that it would be possible to transform and store anything, including all our knowledge of ourselves.

A bit of word-play here may help to ease your mind. “Information” is whatever is “in formation,” that is, defined by its relation to something else. Any transformation is stored as information. So the medium is not only the message, it’s the metaphor, too!

oney is a medium as much as the alphabet, because it provides a means of exchange. The alphabet allows exchange of words and ideas; money allows exchange of commodities and services. Money can also be a commodity in itself when objects that are valued serve as a medium of exchange.

oney is a medium as much as the alphabet, because it provides a means of exchange. The alphabet allows exchange of words and ideas; money allows exchange of commodities and services. Money can also be a commodity in itself when objects that are valued serve as a medium of exchange.

Whales’ teeth, tulip bulbs, and tobacco have all been used as money. A major activity in the financial world is trading where the commodity on the market is the medium of money itself. Bank advertising refers to “financial products” as if money-related services were tangible commodities.

ecause of mankind’s obsession with motion, civilization has been marked by one technology after another extending the human foot. The invention of the wheel eventually led, among others, to the bicycle, the motorcycle, the train, the airplane, and the car. While the motorcycle may be more personal and the airplane more powerful, none of these media has produced such a set of psychological, cultural, and socio-economic effects (through the creation of a huge service environment) as the car:

ecause of mankind’s obsession with motion, civilization has been marked by one technology after another extending the human foot. The invention of the wheel eventually led, among others, to the bicycle, the motorcycle, the train, the airplane, and the car. While the motorcycle may be more personal and the airplane more powerful, none of these media has produced such a set of psychological, cultural, and socio-economic effects (through the creation of a huge service environment) as the car:

Agent of stress, status symbol, transformer of country landscape and cityscapes alike. These features of the car were well understood before McLuhan turned his attention to it.

His analysis focuses elsewhere:

Cars are the population of the city cores they have transformed, and the result has been a loss of human scale

Cars are the population of the city cores they have transformed, and the result has been a loss of human scale

The car is neither less nor more of a sex object than other technologies. It is mankind that functions as the sex organ of all technologies by creating and cross-fertilizing them

The car is neither less nor more of a sex object than other technologies. It is mankind that functions as the sex organ of all technologies by creating and cross-fertilizing them

The demise of the car began with television, because it undermines the uniformity and standardization of assembly-line production with which the car is identified

The demise of the car began with television, because it undermines the uniformity and standardization of assembly-line production with which the car is identified

Acceptance of the limousine as a status symbol, associated with wealth and power, is not an indication of the mechanical age that spawned the car but of the electronic age bringing the older one to a close and redefining status and role

Acceptance of the limousine as a status symbol, associated with wealth and power, is not an indication of the mechanical age that spawned the car but of the electronic age bringing the older one to a close and redefining status and role

For McLuhan, such observations are the key to understanding the car as a medium in relation to other media and their effects on each other and on society.

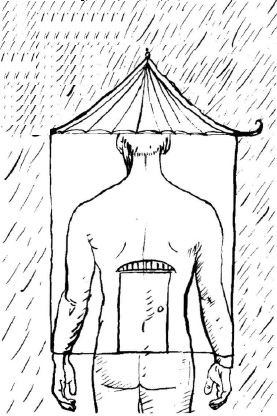

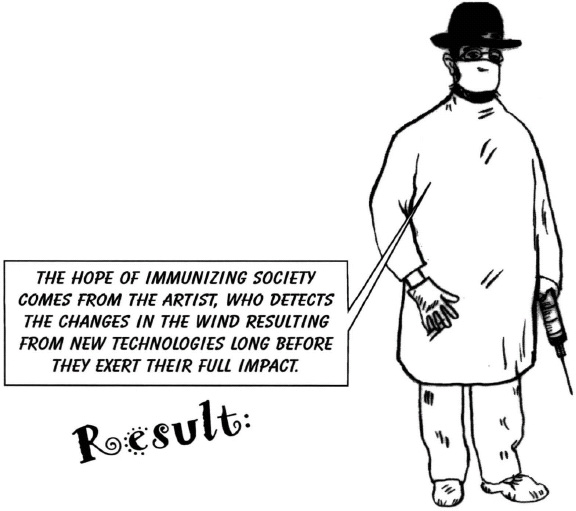

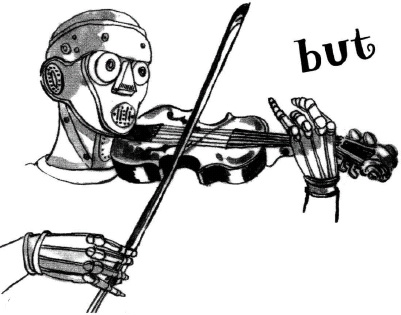

he numbing effect of new media is caused by a shift in sense ratios, McLuhan says. The shift sets in automatically with the arrival of new technologies and acts as a sort of local anaesthetic to make technological change less painful. McLuhan speaks of “huge collective surgery” (Understanding Media, p. 64) carried out on society with the implantation of the new media.

he numbing effect of new media is caused by a shift in sense ratios, McLuhan says. The shift sets in automatically with the arrival of new technologies and acts as a sort of local anaesthetic to make technological change less painful. McLuhan speaks of “huge collective surgery” (Understanding Media, p. 64) carried out on society with the implantation of the new media.

McLuhan goes even further with his medical metaphor: infection can set in during the operation and threaten the whole body, so some measure to provide immunity is called for.

ART FUNCTIONS AS AN ANTI-ENVIRONMENTAL CONTROL

In other words, art protects society from the new environment that technological innovations create, from the inevitable epidemic sweep that follows the introduction of new technology.

McLuhan points out that the French symbolist poets of the late nineteenth century were entirely in harmony with the new breakthroughs in science:

The poets and the scientists were in agreement in seeing RESONANCE as the fundamental quality of the universe.

As for James Joyce (maybe McLuhan’s all time favorite), he understood that the EFFECT of electricity would be the reunification of the Physical SENSES and the RETRIBALIZATION of Western culture.

cLuhan sees no salvation coming from the televangelists, but he speculates on the potential that electronic technology holds for recreating the Pentecostal experience in the global village. The tongues of fire that empowered believers on the day of Pentecost is not just part of the imagery that McLuhan carried with him as a devout Roman Catholic. Fire is the ancient symbol of becoming, of transformation, of transcendence, and so of the power of the Holy Spirit and the power of a medium, combined at Pentecost in language.

cLuhan sees no salvation coming from the televangelists, but he speculates on the potential that electronic technology holds for recreating the Pentecostal experience in the global village. The tongues of fire that empowered believers on the day of Pentecost is not just part of the imagery that McLuhan carried with him as a devout Roman Catholic. Fire is the ancient symbol of becoming, of transformation, of transcendence, and so of the power of the Holy Spirit and the power of a medium, combined at Pentecost in language.

McLuhan refers to language as:

the technology that has both translated (thought into speech) and been translated by other technologies throughout the course of civilisation (hieroglyphics, phonetic alphabet, printing press, telegraph, phonograph, radio and telephone)

the technology that has both translated (thought into speech) and been translated by other technologies throughout the course of civilisation (hieroglyphics, phonetic alphabet, printing press, telegraph, phonograph, radio and telephone)

central to McLuhan’s teachings on media, their transformations, and interactions

central to McLuhan’s teachings on media, their transformations, and interactions

central to the French symbolist poets who saw language as decayed past the point of allowing a new Pentecost.

central to the French symbolist poets who saw language as decayed past the point of allowing a new Pentecost.

McLuhan disagrees with the symbolists, because

ELECTRONIC TECHNOLOGY DOES NOT DEPEND ON WORDS.

ELECTRONIC TECHNOLOGY DOES NOT DEPEND ON WORDS.

since the computer is the extension of the central nervous system, here is the possibility of

extending consciousness without verbalization,

extending consciousness without verbalization,

getting past the fragmentation and numbing effect of language,

getting past the fragmentation and numbing effect of language,

A WAY TO UNIVERSAL UNDERSTANDING AND UNITY.

A WAY TO UNIVERSAL UNDERSTANDING AND UNITY.

espite its title, Understanding Media is not an easy work to understand. In the 1994 reissue of the book, however, Lewis Lapham presents a neat little side-by-side comparison that reduces McLuhan’s assessments of the characteristics of print and electronic media to their lowest common denominators (pp. xii-xiii):

espite its title, Understanding Media is not an easy work to understand. In the 1994 reissue of the book, however, Lewis Lapham presents a neat little side-by-side comparison that reduces McLuhan’s assessments of the characteristics of print and electronic media to their lowest common denominators (pp. xii-xiii):

Print Media

visual

mechanical

sequence

composition

eye

active

expansion

complete

soliloquy

classification

center

continuous

syntax

self-expression

Typographic Man

Electronic Media

tactile

organic

simultaneity

improvisation

ear

reactive

contraction

incomplete

chorus

pattern recognition

margin

discontinuous

mosaic

group therapy

Graphic Man

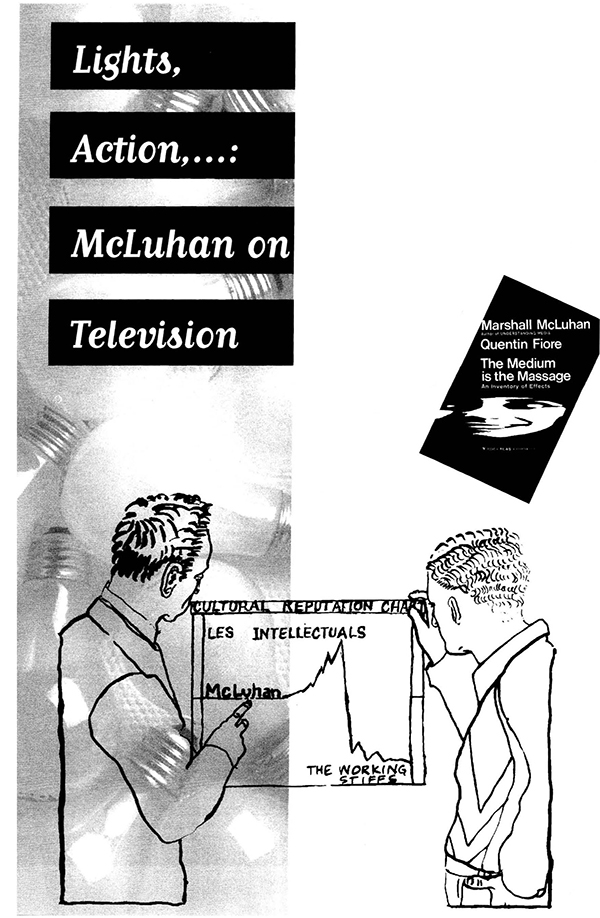

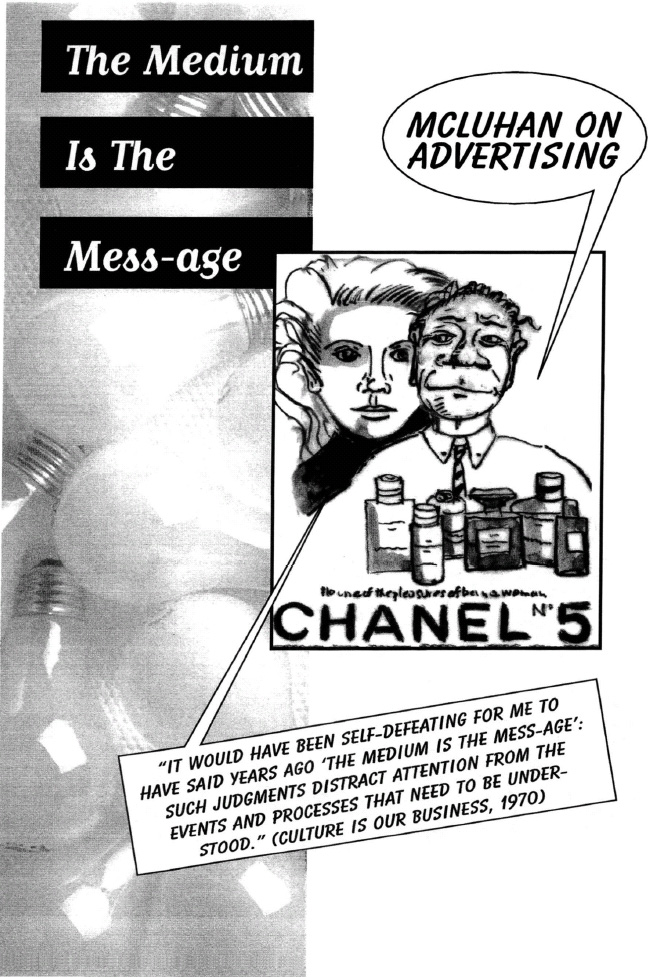

After Understanding Media, McLuhan collaborated with Quentin Fiore on The Medium is the Massage: An Inventory of Effects (1967). One critic, who calls this work “the million-selling, McLuhan Made Easy paperback,” notes also that it “eroded [McLuhan’s] reputation among the intelligentsia even as it secured it among the masses” (Dery, 1995, p. 24).

The pun in the title underscores both McLuhan’s unwillingness to take himself too seriously and his characteristically witty ideas about the most far-reaching of media effects, that of creating complete—and completely new—environments for society. To quote McLuhan, like the masseuse, “all media work us over completely.” The metaphor is also linked to McLuhan’s observations that art, not media, provides a means for societies and individuals to recover from the numbing, massage-like effect created when the body of society is touched at every point by technological innovation.

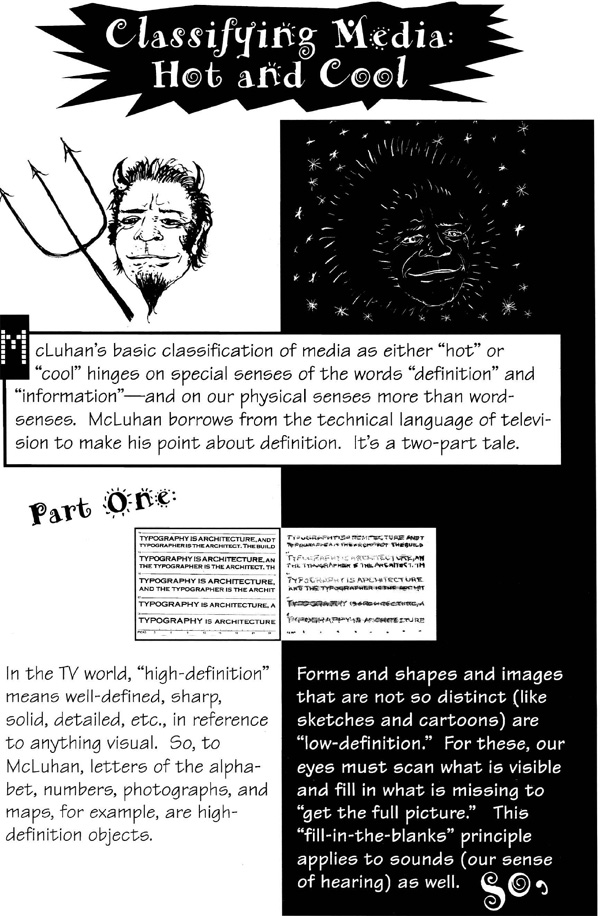

In Massage, McLuhan likens the image on a television screen to a flat, two-dimensional mosaic. Unlike the hot medium of print, he contends, the TV mosaic does not have a visual structure that allows the eye to race in a straight line over sharply defined forms. It does not have uniform, continuous, or repetitive features, nor does it extend sight to the exclusion of the other senses. Rather, he claimed that TV has a tactile quality—discontinuous and nonlinear—like the features of a mosaic. Television images, though received by the eye, were viewed by McLuhan as primarily extensions of the sense of touch. The image on the screen has the type of texture associated with touch. Additionally, while it provides a minimum of information, television creates an interplay of all the senses at once, whereas print media separate and fragment the physical senses.

It was this all-at-onceness, he claimed, that forced....the GREAT DIVIDE... A shift from:

A world based on low-involvement, monosensory print media

[LOOK OUT BELOW!!]

A world based on high-involvement, multisensory electronic media

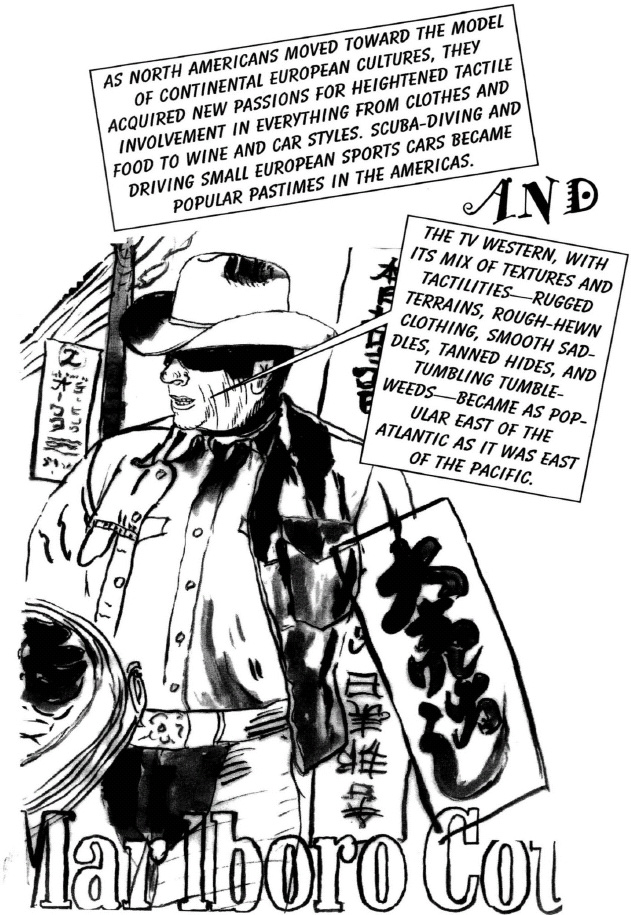

McLuhan argued that with the introduction of television in the 1950s, the abstract-visual sense that had dominated Western culture for centuries through the alphabet and printing press was abruptly dislocated. The impact of such a reorganization was particularly strong in North America and England, whose cultures had been intensely literate for so long. The changes in social trends and values influenced by television were immediate and profound. As McLuhan points out:

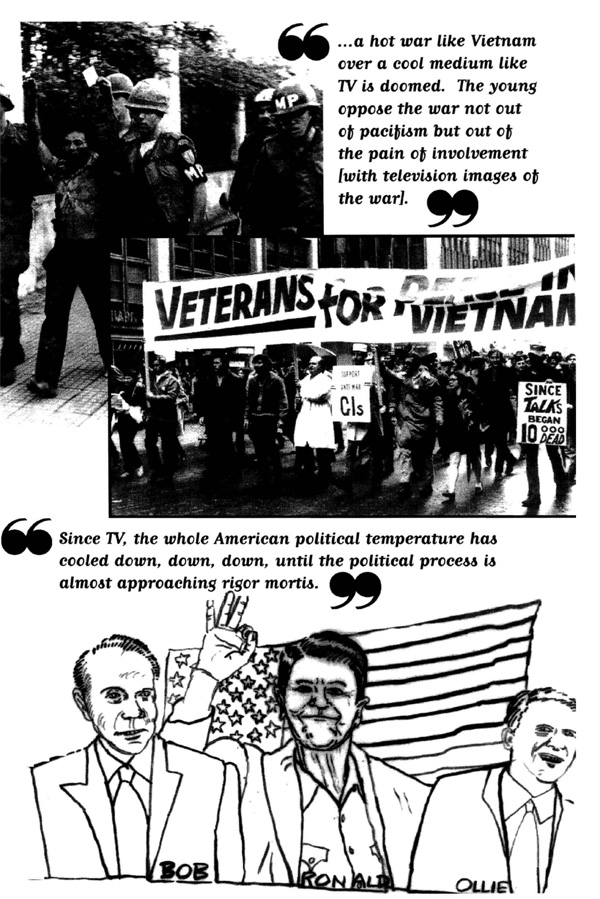

Further, McLuhan claimed that television’s (and other high speed electronic media’s) all at-onceness—its ability to transmit images and information from a variety of sources, places, and times—prompted the world to contract into a “global village in which everyone is involved with everyone else—the haves with the have-nots,...Negroes with whites,...adults with teenagers.” On television, McLuhan noted, everything everywhere happens simultaneously, with no clear order or sequence. He credited the medium with a wide range of changes in the American social and political scene:

Television brings not only the voting booth into the Living room but also the civil-rights march along Alabama’s U.S. 80 and the bull-dozing of a village in Vietnam-and involves the audience intimately...

Television brings not only the voting booth into the Living room but also the civil-rights march along Alabama’s U.S. 80 and the bull-dozing of a village in Vietnam-and involves the audience intimately...

Without television, there would be no civil-rights legislation.

Without television, there would be no civil-rights legislation.

McLuhan also noted a strange paradox: TV viewers’ high involvement with the images projected on the screen minimized rather than heightened the need of viewers to respond to what they see on TV. For example:

The Kennedy event [the 1963 funeral of slain President John F. Kennedy] provides an opportunity for noting a paradoxical feature of the 'cool' TV medium. It involves us in moving depth, but it does not excite, agitate or arouse.

The Kennedy event [the 1963 funeral of slain President John F. Kennedy] provides an opportunity for noting a paradoxical feature of the 'cool' TV medium. It involves us in moving depth, but it does not excite, agitate or arouse.

McLuhan observed that the television screen is a mesh of dots through which light shines with varying intensity to allow an images to form—but not before the spaces in the mesh are “Closed” He referred to this process of closure as “a convulsive sensuous participation that is profoundly kinetic and tactile” (Understanding Media, p. 314) [Wow! Remember, touch was one of McLuhan’s all-time “pick” senses!] But, to McLuhan, closure did not refer merely to closing up the spaces in the mesh of dots on the television screen, but to the closing down of one physical sense when another is extended by a new medium.

Closure, of the television sort, also marked for McLuhan a shift toward a new balance among our senses: while television reawakens our tactile sense, it diminishes the visual sense relied upon in a purely print culture and replaces it with an all-encompassing sensory experience. There is, of course, no contact between the skin of the viewer and the television, but, according to McLuhan, the eye is so much more intensely engaged by the television screen than by print that the effect is the same as that of touching!

McLuhan saw a down-side to this sensory closure thing, however, claiming that it causes conformity to the pattern of experience presented by a medium. He issued a sterner warning in Understanding Media, likening TV to a disease:

This warning also shows us that to take McLuhan as a promoter of television is to miss an important part of his teaching. Indeed, he cautioned that not even his insights into the operation and power of media could offset “the ordinary ‘closure’ of the senses” (Understanding Media). And remember, he didn’t want his own grandkids growing up glued to the tube!

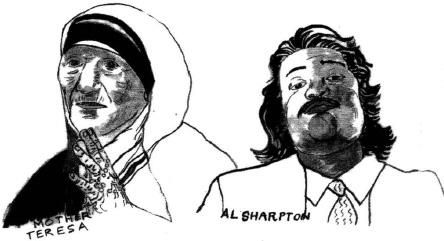

Television “Types”

McLuhan had lots to say about who (the kinds of people) or what (the kind of image) were most suitable for television. TV viewers, he claimed, because of the sensory involvement the medium demands and the habits of perception it imposes, come to expect not a “fixed” image but one they are required to “fix.” Thus, persons who represent a “type”—that is, those whose physical appearances make a statement about their role and status in life—overheat the cool medium of TV, depriving its viewers of the task of closure. Successful TV personalities, McLuhan claimed, were those whose appearance fed the medium’s need for texture with (for example):

However, McLuhan allowed that persons who are neither shaggy, craggy, nor sculptured could nevertheless project an acceptable television presence—if they fed the cool medium’s other fundamental need: for free-flowing chat and dialogue. This explained, to McLuhan, at least, why, in the earliest days of television, someone like talk show host

McLuhan drew no sharp distinctions between television’s role as an entertainment medium and as an educational tool. He did note, however, that traditional pedagogical techniques, developed during the Print Age and incorporating all the visual biases of print, became less effective with the advent of television. He called for greater understanding of the dynamics of this powerful medium, its action on our senses, and its interaction with other media. Simply showing teachers teaching on TV, he claimed, was a useless overheating of the cool medium of television. Yet, there were some things he believed television could do that the classroom could not: “TV can illustrate the interplay of process and the growth of forms of all kinds as nothing else can” (Understanding Media, p. 332). He advised teachers “not only to understand the television medium but to exploit it for its pedagogical richness” (Understanding Media, p. 335).

Lewis Lapham, in the Introduction to the thirtieth anniversary edition of understanding Media, summarizes McLuhan’s insights about advertising:

mcLuhan notices, correctly, that it is the bad new—reports of sexual scandal, natural disaster, and violent death—that sells the good news—that is, the advertisements. The bad news is the spiel that brings the suckers into the tent....The homily is as plain as a medieval morality play or the bloodstains on [“miamivice” star] Don Johnson’s Armain suit—obey the law, pay your taxes, speak politely to the police officer, and you go to the Virgin Islands on the American Express card. Disobey the law, neglect your insurance payments, speak rudely to the police, and you go to kings county Hospital in a body bag.”