The comics engage McLuhan’s attention as a reflection of popular culture (and as an example of a “cool” medium). Some comic strips he condemns, others he praises. The point, in either case, is to create a full awareness of the biases the strips adopt, the models they use, and the values they perpetuate.

In Little Orphan Annie, McLuhan sees the American success story grounded in the psychological need to achieve that success by both pleasing parents and outdoing them. Voluntary orphanhood. Its frightening aspects of isolation and helplessness are mitigated by Annie’s character—her innocence and her goodness—and, of course, by her success in doing battle, as valiantly as Joan of Arc, against incompetence, interference, stupidity, and evil.

The adventures of Superman, McLuhan observes, go beyond tales of the science-fiction type to dramatize the psychological defeat of technological man. Always the victor when sheer force can bring the victory, Superman is nothing but the alter ego of the incompetent and vilified Clark Kent, a wish fulfillment in a man whose persona suggests to McLuhan a society reacting to the pressures of the technological age, rejecting civilizing processes such as due process of law, and embracing violence.

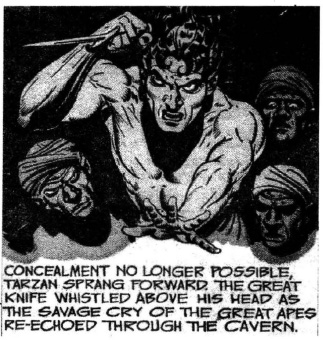

It is significant that Tarzan, like Superman, has an alter ego in the person of Lord Greystoke. By contrast with the downtrodden Clark Kent, Greystoke is what McLuhan calls “the unreconstructed survivor of the wreck of feudalism.” (The Mechanical Bride, p. 104) He is outside the duality of noble savage/civilized man, an aristocrat who forsook the salon for the jungle, a hybrid in whom the ideals of the Y.M.C.A., Kipling, and Baden-Powell come together.

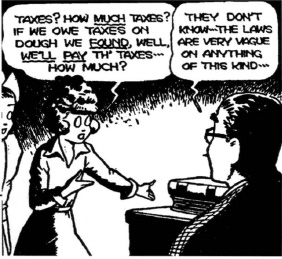

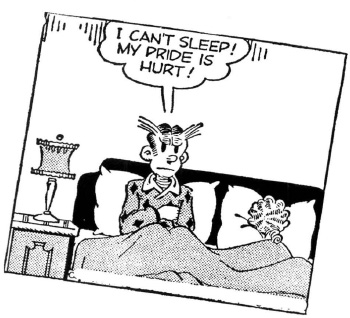

cLuhan’s least favorite strip was Blondie, because it was pure formula—repetitive and predictable. Dagwood is trapped in suburban life, frustrated, and victimized. He gets little sympathy from his children and none from McLuhan. Where readers might find Dagwood’s midnight trips to the refrigerator comical, McLuhan finds them contemptible: “promiscuous gormandizing as a basic dramatic symbol of the abused and the insecure.” (The Mechanical Bride, p. 68) Unlike Jiggs, in Bringing Up Father, who belongs to the first generation of his family to have realized the American dream, Dagwood is second generation and lacking the competitiveness that motivated his father to realize that dream. Nearly fifty years ago, McLuhan surmised that “Chic Young’s strip seems to be assured of survival into a world which will be as alien to it as it already is to McManus’s Jiggs.” (The Mechanical Bride, p. 69)

cLuhan’s least favorite strip was Blondie, because it was pure formula—repetitive and predictable. Dagwood is trapped in suburban life, frustrated, and victimized. He gets little sympathy from his children and none from McLuhan. Where readers might find Dagwood’s midnight trips to the refrigerator comical, McLuhan finds them contemptible: “promiscuous gormandizing as a basic dramatic symbol of the abused and the insecure.” (The Mechanical Bride, p. 68) Unlike Jiggs, in Bringing Up Father, who belongs to the first generation of his family to have realized the American dream, Dagwood is second generation and lacking the competitiveness that motivated his father to realize that dream. Nearly fifty years ago, McLuhan surmised that “Chic Young’s strip seems to be assured of survival into a world which will be as alien to it as it already is to McManus’s Jiggs.” (The Mechanical Bride, p. 69)

To McLuhan’s great satisfaction, the mind-set that keeps Dagwood and his fans alike trapped in a glass time-capsule is shattered by Al Capp’s Li’l Abner. Capp’s satire, irony, and freedom from sentimentality all work toward the development of sharpened perception—the very purpose of McLuhan’s own program. The multi-dimensional approach the program requires is paralleled by the mosaic of hero images that is Li’l Abner himself. The real hero for McLuhan is Capp in his endless quest to reveal the delusions and illusions foisted on society by politicians, business, and the media. McLuhan made no prediction for the future of Al Capp’s strip, and unlike Dagwood, Li’l Abner has not survived, confirming McLuhan’s observation that society prefers somnambulism to awareness.

SMILE, IF IT PLEASES YOU, AT THE DEADPAN DESCRIPTION OF COMIC STRIPS (MCLUHAN CERTAINLY WOULDN’T MIND) JUST BEAR IN MIND THAT NEARLY A DECADE BEFORE ANDY WARHOL LED THE POP ART REVOLUTION, SHERLOCK MCLUHAN WAS ALREADY ON THE CASE.