Confusion

Perspective

The term confusion connotes an alteration in higher cerebral functions, such as memory, attention, or awareness. In addition, the ability to sustain and focus attention is impaired. Confusion is a symptom, not a diagnosis. The degree of confusion may fluctuate, as may the patient's level of consciousness. Clinical jargon includes the phrases “altered mental status,” “delta MS” (change in mental status), “altered mentation,” and “change from baseline.” Implicit in the definition is a recent change in behavior. Chronic mental status changes such as dementia typically have a different clinical chronology. Other forms of altered mentation include states of diminished alertness on the coma spectrum; these presentations may result from some of the same pathophysiologic processes causing confusion and are discussed in Chapter 16. Confusion may range in severity from a mild disturbance of short-term memory to a global inability to relate to the environment and process sensory input. This extreme state is termed delirium. Delirium has two subtypes: hyperactive and hypoactive.1 Hyperactive delirium is characterized as an acute confusional state associated with increased alertness, increased psychomotor activity, and disorientation and is often accompanied by hallucinations. In hypoactive delirium (sometimes referred to as quiet delirium), the confusional state is present but the patient has a reduction in alertness and behavior. Hypoactive delirium may be the more common type in emergency department (ED) patients.2 Confusion has many causes, and an orderly approach is necessary to discover the causative diagnosis. The assessment of mental status and cognitive impairment in elderly ED patients has been proposed as a key quality indicator in the care of elderly patients by the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine Geriatric Emergency Medicine Task Force.3

Epidemiology

Physicians underestimate the incidence of confusion in patients.4,5 Often, confusion is accepted as an incidental or secondary component of another condition. A patient with injuries from a motor vehicle crash or with dyspnea may be confused, but the primary condition overshadows the underlying abnormal mental status. When confusion exists as an isolated or unexplained finding, it is more likely to receive full and immediate consideration by the clinician. Confusion is estimated to occur in 2% of ED patients, 10% of all hospitalized patients, and 50% of elderly hospitalized patients.4,6 Delirium in older ED patients was found to be an independent predictor of increased mortality within 6 months in one study.7

Pathophysiology

Conceptually, consciousness may be divided into elements of alertness or arousal and elements constituting content of consciousness. Confusion is largely a problem of the content portion of consciousness. Many different clinical processes may disrupt optimal cortical functioning and result in confusion. The pathophysiology is not straightforward. Widespread cortical dysfunction is thought to result from substrate deficiencies (hypoglycemia or hypoxemia), neurotransmitter dysfunction, or circulatory dysfunction. Compounding this problem is the concept that the reserve of central nervous system (CNS) function varies from individual to individual; individuals with a preexisting impairment may become confused after even minor changes in their normal physiologic state.

Diagnostic Approach

The observation of acute confusion prompts a search for an underlying cause. Four groups of disorders encompass most causes of diffuse cortical dysfunction: (1) systemic diseases secondarily affecting the CNS, (2) primary intracranial disease, (3) exogenous toxins, and (4) drug withdrawal states (Box 17-1).1 Focal cortical dysfunction, such as from tumor or stroke, typically does not cause confusion, although occasionally, receptive or expressive dysphasia may be mistaken for confusion. Likewise, subcortical or brainstem dysfunction most frequently results in a diminished level of alertness and consciousness, not confusion.

Rapid Assessment and Stabilization

Most patients with acute confusion do not require immediate interventions. Three crucial exceptions are hypoglycemia, hypoxemia, and shock. A complete set of vital signs, including temperature and oxyhemoglobin saturation, and a bedside blood glucose level should be determined promptly for all confused patients. Oral or intravenous glucose therapy is indicated if low blood glucose is discovered. Supplemental oxygen and intravenous fluid are administered as necessary. In a patient with abnormal or unstable vital signs, initial diagnostic and management efforts are directed toward treatment of the systemic condition. A confused patient with acute pulmonary edema, hypoxia, and confusion obviously requires evaluation and treatment of the pulmonary edema, not a screening test for cognitive functioning.

Confused patients should be protected from harming themselves or others. Close observation may need to be supplemented by medications or physical restraint. Family members may offer valuable assistance in observing and comforting the patient.

In general, in patients with schizophrenia and other psychiatric disorders, results of tests of cognition, orientation, and attention are normal unless the condition is severe. The term psychosis implies a disorder of reality testing and thought organization severe enough to interfere with normal daily functioning. Psychosis is a nonspecific syndrome, and careful evaluation is required to differentiate between psychiatric and organic origins (e.g., drug intoxication or other systemic process) (Box 17-2).

Pivotal Findings

A patient with an altered state of consciousness including confusion is evaluated through a focused history and a pertinent examination, performance of rapid bedside screening investigations, and observation of the response to certain therapies (e.g., dextrose or naloxone). Additional evaluation may include laboratory testing and diagnostic imaging with various modalities. Information that suggests the cause of confusion is found roughly in descending order from the patient's history, the examination findings including results of rapid bedside testing, and the response to ED therapies; the results of laboratory testing and diagnostic imaging are less often useful.8

History

Confusion is often reported by family members or caregivers; frequently the patient is not aware of the confusion and seemingly glosses over problems. Families may articulate the complaint as confusion but also may describe rambling, disorientation, speaking to persons not there, the patient's inability to find his or her way around familiar surroundings, or simply “not being right.” An essential goal of the history is to determine when the patient last exhibited “normal” thinking and behavior.

Attention deficit is the common denominator in confusional states. The initial task in evaluating the patient is to define the symptoms and severity of confusion. The specific behaviors that are of concern to the patient or caregivers should be defined. Often the family is the most valuable source for information; a physician or other caregiver with an established relationship with the patient also may be helpful. The duration of the confusion, any recent changes in medications, and recent illnesses are important points in the clinical history. Hallucinations are not unique to psychiatric illness and can commonly occur in confusion states, especially delirium. Hallucinations in delirium tend to be visual (with or without auditory components), powerful, fleeting, and poorly organized. A history of medication or substance abuse and any recent changes, especially cessation of benzodiazepines or ethanol, should be sought.

Physical Examination

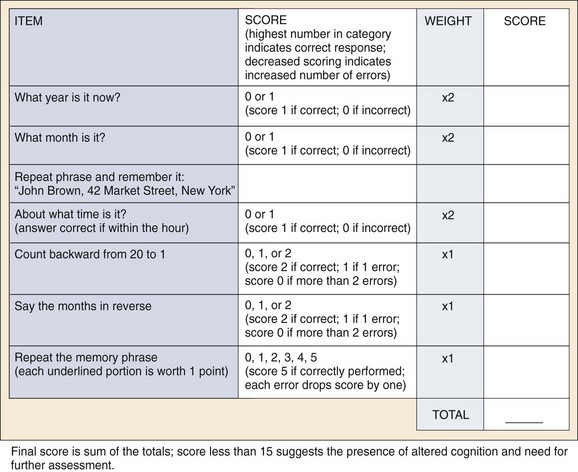

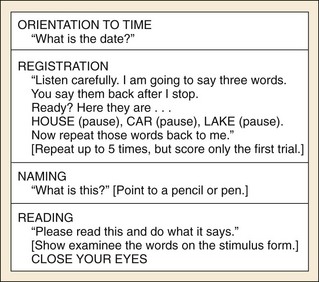

The patient's confusion may be obvious at the bedside. In other cases, confusion may be subtle, and informal assessment of mental status and cognitive abilities may fail to detect it. The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (Fig. 17-1) commonly is recommended as a screening instrument but is used infrequently in the ED because of the time required for administration.8,9 A more rapidly performed screening tool, the Quick Confusion Scale (QCS; Fig. 17-2), has been developed and tested in ED patients.9,10 This tool objectively measures elements of the patient's mental status in 2 to 3 minutes and correlates well with the MMSE.10,11 Another rapid scale, the Six-Item Screener, has similar performance against the MMSE.12,13 The tasks measured by either the MMSE or the QCS require adequate attention on the part of the patient. If the patient's attention span is greatly impaired, detailed testing may be impossible. Digit repetition forward (five or six digits) and backward (four digits) is a brief screen for attention function. Alternatively, spelling a commonly used word backward (“world” is frequently used) measures a patient's ability to concentrate. Screening tests may detect confusion not obvious in casual conversation, identifying the need for further investigations.12,14 A recently described cognitive assessment tool, the Sweet 16, has been studied in patients in the posthospitalization period.15 A variety of other bedside instruments are available as screening tests for delirium.16

Figure 17-1 Mini-Mental State Examination sample items. (Reproduced by special permission of the Publisher, Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc., 16204 North Florida Avenue, Lutz, Florida 33549, from the Mini-Mental State Examination, by Marshal Folstein and Susan Folstein. Copyright © 1975, 1998, 2001 by Mini Mental LLC, Inc. Published 2001 by Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc. Further reproduction is prohibited without permission of PAR, Inc. The MMSE can be purchased from PAR, Inc., by calling [800] 331-8378 or [813] 968-3003.)

The physical examination may suggest a cause of confusion such as congestive heart failure, pneumonia, or stigmata of illicit drug use. Fever suggests an infection as the cause of altered mental status and should prompt a search for the source, particularly urinary tract infection in the elderly patient. Any new focal neurologic findings suggest a possible mass lesion or stroke, but these would manifest with confusion only if global cortical dysfunction was caused by surrounding cerebral edema or elevated intracranial pressure by severe mass effect. In this regard, testing of gait and tandem gait, if possible, may be invaluable. Aphasia, fluent or nonfluent, is a focal sign suggesting a lesion in the dominant cerebral hemisphere. In confusional states, speech may be abnormal and is often incoherent, and the rate of speech may be either rapid or slowed. Involuntary movements, such as asterixis or tremor, may be present. The various toxidromes may assist in the identification of an intoxication or drug effect as the cause of confusion.

Laboratory Tests

The results of the history and physical examination frequently guide the clinician in the choice of laboratory tests most likely to yield valuable diagnostic information. Pulse oximetry may reveal hypoxia, or bedside glucose testing may reveal hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia. In the presence of a fever, chest radiography and urinalysis often reveal the source of the infection causing the altered mentation. In elder patients, urinalysis should be performed whether or not fever is present. A careful inspection of the skin, especially in dependent areas, such as the buttocks, may reveal a culprit skin infection. Serum electrolyte testing (especially sodium) is indicated in all cases. Broader chemistry panels, including liver enzymes, help identify hepatic encephalopathy. If there are clinical findings suggestive of hypothyroidism, thyroid testing is indicated. (See Chapter 128.) Electrocardiography is indicated in elderly patients because myocardial infarction may manifest atypically as confusion. The complete blood count, although commonly performed, is unlikely to provide useful diagnostic clues, unless profound anemia is suspected. Arterial blood gas testing is rarely indicated or useful unless pulse oximetry is not reliable.

If common and simple tests do not suggest a solution, more complex tests are initiated in the ED, observation unit, or inpatient service. The clinical situation and overall condition of the patient determine the speed and direction of evaluation. Additional laboratory work is often of decreasing yield but may reveal the cause of confusion. Serum ammonia, calcium, and selected drug and toxicologic testing may be ordered in this second tier of evaluation. Blood and urine cultures are obtained in the febrile patient when hospital admission is anticipated and a clear infectious source is not evident. Paracentesis or thoracentesis may be appropriate if ascites or pleural effusion is present. Cranial computed tomography (CT) scanning is usually done to screen for CNS lesions in the absence of another identified source of the confusion. Focal findings on examination increase the yield of this test, but unanticipated abnormalities are often found on neuroimaging. Lumbar puncture may allow discovery or exclusion of CNS infection if no other source has been identified. Cerebrospinal fluid examination may clarify a diagnosis of bacterial meningitis, encephalitis, aseptic meningitis, or subarachnoid hemorrhage. If the cause of confusion remains unclear or if the patient is unable to function safely in his or her current environment, admission may be necessary for additional ongoing assessment, including diagnostic testing not usually available in the ED, such as magnetic resonance imaging or electroencephalography.8

Differential Diagnosis

Certain critical and emergent diagnoses require prompt recognition for morbidity or mortality to be prevented (Box 17-3). The diagnosis of confusion implies the exclusion of other states of altered mental status, such as coma and decompensated psychiatric syndromes. A new focal neurologic deficit points to a focal defect of the CNS, which is less likely to cause the global cortical dysfunction necessary for confusion. Stroke rarely causes confusion, but resulting disturbances in speech or understanding may mimic a confusional state. The diagnosis of stroke is relatively straightforward if a new motor deficit is present. Occasionally, other focal neurologic abnormalities may mimic a confusional state. A person with a new visual field deficit and visual neglect may have difficulty ambulating in familiar surroundings and be labeled as confused, but this reflects focal neurologic injury and not a confusional state from global CNS dysfunction. Careful assessment of mental status assists in resolving the diagnostic dilemma. Frontal lobe dysfunction from stroke, subdural hematoma, or tumor may result in personality changes and the report of “confusion” by family or friends.

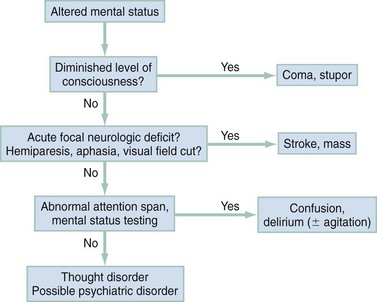

Altered mental status may be divided into three different categories depending on the finding of diminished level of consciousness, acute focal neurologic deficit, or abnormal attention span. Placement into one of these categories may guide the differential assessment and therapy (Fig. 17-3).

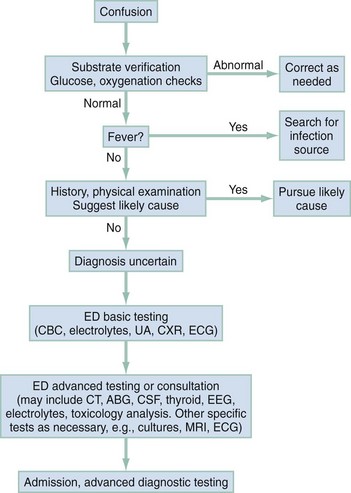

Empirical Management

Ideally, treatment is directed at the underlying cause of the confusion. Investigations continue until a likely diagnosis is discovered or consultation and admission are deemed necessary (Fig. 17-4). Many febrile patients are found to have a systemic infectious cause of the confusion. Urinary tract infections and pneumonia are the more common sources, but soft tissue infections also warrant consideration. CNS infections are encountered less frequently but have potentially devastating consequences if not recognized promptly. Antibiotic treatment for coverage of common causes of meningitis may be considered in ill febrile patients while definitive evaluation is in progress.

Figure 17-4 Management algorithm for confusion. ABG, arterial blood gas; CBC, complete blood count; CT, computed tomography; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; CXR, chest x-ray examination; ECG, electrocardiogram; ED, emergency department; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; UA, urinalysis.

Postictal confusion is common in patients with seizures but should improve within 20 to 30 minutes. If the patient remains unconscious or confused after a seizure, the possibility of ongoing or intermittent seizure activity (i.e., nonconvulsive seizures) should be considered. Nonconvulsive status epilepticus, an epileptic twilight state, is unusual but does occur and may be particularly difficult to recognize in the elderly (see also Chapters 18 and 102).17

Sometimes it may be necessary to treat confusion or agitation for patient safety. Environmental manipulations such as dim lighting or provision of psychosocial support may be helpful. Confinement or physical restraint may be necessary at times for patient safety with careful adherence to institutional guidelines. Benzodiazepines, butyrophenones, or newer antipsychotic medications may be used if necessary to decrease agitation, but any of these might confound evaluation of the confusional state.

Disposition

Most patients with a presenting sign of confusion are admitted to the hospital or ED observation unit for additional diagnostic procedures, extended observation, and treatment. Exceptions include patients with rapidly resolved confusional states after treatment for insulin-induced hypoglycemia, or after recovery from intoxications or withdrawal states, such as those related to ethanol or recreational drugs. These patients may be observed and then discharged after successful identification and resolution of the acute confusional state. Unresolved confusion or unexplained findings on repeat mental status screening should prompt admission or careful reevaluation before consideration of discharge.

References

1. Lipowski, ZJ. Delirium (acute confusional states). JAMA. 1987;258:1789.

2. Han, JH, et al. Delirium in older emergency department patients: Recognition, risk factors, and psychomotor subtypes. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:193.

3. Terrell, KM, et al. Quality indicators for geriatric emergency care. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:441.

4. Hustey, FM, Meldon, SW. The prevalence and documentation of impaired mental status in elderly emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;39:248.

5. Sanders, AB. Missed delirium in older emergency department patients: A quality-of-care problem. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;39:338.

6. Wofford, JL, Loehr, LR, Schwartz, E. Acute cognitive impairment in elderly ED patients: Etiologies and outcomes. Am J Emerg Med. 1996;14:649.

7. Han, JH, et al. Delirium in the emergency department: An independent predictor of death within 6 months. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56:244.

8. American College of Emergency Physicians. Clinical policy for the initial approach to patients presenting with altered mental status. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;33:251.

9. Folstein, MF, Folstein, SE, McHugh, PR. “Mini-mental state”: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189.

10. Huff, JS, Farace, E, Brady, WJ, Kheir, J, Shawver, G. The Quick Confusion Scale in the ED: Comparison with the Mini-Mental State Examination. Am J Emerg Med. 2001;19:461.

11. Irons, MJ, Farace, E, Brady, WJ, Huff, JS. Mental status screening of emergency department patients: Normative study of the Quick Confusion Scale. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9:989.

12. Wilber, ST, Lofgren, SD, Mager, TG, Blanda, M, Gerson, LW. An evaluation of two screening tools for cognitive impairment in older emergency department patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:612.

13. Stair, TO, Morrissey, J, Jaradeh, I, Zhou, TX, Goldstein, JN. Validation of the Quick Confusion Scale for mental status screening in the emergency department. Intern Emerg Med. 2007;2:130.

14. Hustey, FM, Meldon, SW, Smith, MD, Lex, CK. The effect of mental status screening on the care of elderly emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;41:678.

15. Fong, TG, et al. Development and validation of a brief cognitive assessment tool: The sweet 16. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:432.

16. Wong, CL, Holroyd-Leduc, J, Simel, DL, Straus, SE. Does this patient have delirium? Value of bedside instruments. JAMA. 2010;304:779.

17. Beyenburg, S, Elger, CE, Reuber, M. Acute confusion or altered mental state: Consider nonconvulsive status epilepticus. Gerontology. 2007;53:150.