A pedestrian bridge links White Provision, a mixed-use development in midtown Atlanta, to an adjacent commercial development.

JOHN CLEMMER PHOTOGRAPHY

Subdivision of land is the principal mechanism by which communities are developed. Technically, subdivision describes the legal and physical steps a developer must take to convert raw land into developed land. This chapter examines those steps, which may apply to tracts of any size, for any use, using the development of small residential subdivisions as an example. Subdivision is a vital part of a community’s growth, determining major elements of its appearance, its mix of land uses, structures of governance, and basic infrastructure, including roads, drainage systems, water, sewerage, and public and private utilities. Subdivision regulations have evolved from earlier rules as requirements and preferences have changed for adequate streets, utilities, setbacks, and development densities to create a suitable living environment while protecting valuable ecological and cultural resources.

Developers and planners have often led the way toward better regulation, their projects demonstrating how improved standards can lead to superior development patterns for communities. Developers must be mindful of the impact that their projects may have on local communities. Even when their projects conform to existing zoning requirements, developers must justify their projects to local communities in terms of beneficial (or at least not adverse) effects on the environment, traffic, tax base, schools, parks, and other public facilities. Thus, in the broader sphere of urban development, developers must respect the symbiotic relationships that tie the private and the public sectors together.

The subdivision process generally takes place in three stages: raw land, semideveloped land (usually divided into 20- to 100-acre [8–40 ha] tracts1 with roads and utilities extended to the edge of the property), and developed or subdivided land, platted into individual homesites and 1.5- to ten-acre (0.6–4 ha) commercial parcels, ready for building. The latter is typical for large projects on previously undeveloped parcels. Smaller projects and infill and redevelopment sites typically skip the second phase. The process of converting raw land to semideveloped land differs from region to region, depending on the pattern of landownership, the capacity of local developers and financial institutions, legal frameworks of local and state authority, and the institutional mechanisms for providing roads and utilities.

To ease the conversion process, some states, such as California and Texas, rely heavily on special districts created to finance utility services. Where such vehicles do not exist, developers must wait for the community or utility company to furnish utility service, pay for the extension of roads and utility lines themselves, or form consortiums with other landowners to pay for shared road and utility extensions.

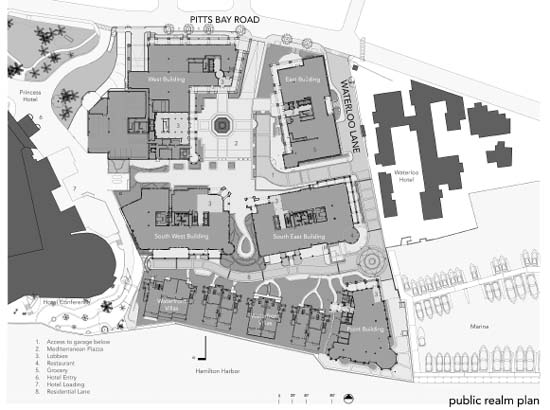

Conversion of raw land to semideveloped land tends to be a project for larger, well-capitalized developers. Such developers typically work with 200- to 1,000-acre (81–405 ha) tracts of land, which they subdivide into smaller 20- to 100-acre (8–40 ha) parcels. They provide the major infrastructure, including arterial roads, Utilities, and drainage systems for the smaller parcels so that they can subsequently be subdivided into buildable lots. Figure 3-1 shows the structure of the land conversion industry and the roles of typical players.

In suburban fringe areas, the developer may skip the second stage and convert the raw land directly to subdivided lots. Direct conversion is more common in slower-growth areas and in places where municipal utility companies or cooperatives install the utilities. Land does not become available for development in a smooth pattern. Rather, farmers, timber interests, and other landholders may sell parcels for reasons such as a death or retirement, an impending change of land use law or zoning, or simply in response to an attractive offer. Because large, contiguous tracts of land rarely become available at one time, leapfrog development that pushes farther away from the city center and low-density sprawl often occur.2 Sprawl results in inefficient use of roads and other infrastructure and the inability to provide municipal services, such as mass transit, emergency services, and utilities, in a cost-effective manner. Leapfrogging, however, may lead to opportunities for small developers. The land parcels that are passed over during the first wave of development can offer opportunities for infill projects. Such sites, while not without difficulties, are often better located and more competitive in terms of market potential than greenfield sites farther from the city. The complexity of developing such parcels can also serve as a barrier to entry, thus reducing competition from regional and national developers who often value repeatable and predictable processes over any particular site or submarket.

Developers must understand the dynamics of market and regulatory forces. They must be politically astute because they serve as the primary agents of physical change in a community. Residents tend to resist change and fight new development unless it offers them a tangible benefit. Developers must gain the support of those who play major roles in determining local land use: elected officials, planning and zoning boards, utility companies, regional air and water quality commissions, traffic commissions, governance boards, press and other opinion leaders, and increasingly well-organized citizens groups and neighbors.

Developers should also be adept in dealing with multiple government jurisdictions because the appropriate jurisdiction for a given use, on a given parcel, may be unclear, particularly in unincorporated areas.

Historically, developers could safely assume a right to develop land as long as they met the zoning and other land use requirements, but this presumption of development rights has largely dissolved. Even when a project conforms to existing zoning, development rights may be subject to reduction, phasing, or outright moratorium, depending on the attitudes of neighboring residents and the political environment. The likelihood of obtaining necessary approvals in a timely fashion is one of the major risks that developers must evaluate before committing themselves to a project. Developers should be well versed in local politics and have an abundance of personal alliances, as even relatively problem-free tracts may require a lengthy approval process before a project can proceed. Successful developers know that the difficulty of the approval process can be as much about sequence and timing as cost. Poor coordination among reviewing agencies can increase timelines substantially. Even a well-conceived project can lose money by taking too long to get to market.

Developers must be involved in the regulatory process and must help educate their communities. Many communities have found that poorly conceived antigrowth measures can have unintended consequences, such as raising housing prices or exacerbating sprawl. In recent years, the concept of “smart growth” has gained support among planners and developers as a way of accommodating inevitable growth while addressing livability, the environment, and the economy by directing growth toward urban centers, transit infrastructure, employment centers, and public amenities (see chapter 8).3 Where growth occurs in exurban areas, developers have advanced concepts of “conservation development” to minimize the footprint of growth and mitigate impacts on agricultural and environmental assets.

FIGURE 3-1 | Types of Land Investors

Developers have become advocates for affordable housing, both in the sense of legally defined affordability, with incentives and financing alternatives driving a competitive business toward this mission, and in the sense of market-based innovation in starter homes and more modestly priced, land-conserving housing solutions.

This chapter focuses on small-scale land development, typically involving 20 to 100 acres (8–40 ha). Although the techniques described here apply to any form of land development, beginning developers are most likely to become involved with small residential or mixed-use subdivisions, and warehouse or light-industrial development.

Many developers engage in both land development (sometimes called “horizontal development”) and building development (vertical building). When they perform both activities on the same tract, they often view the two activities as a single project. They are actually distinct types of development, and each should be analyzed on its own merits. In modeling a project, such analysis amounts to considering oneself the purchaser of finished lots, so that returns can be analyzed on both components of the business independently.

Many considerations arise when a developer is in charge of both land and building development on the same property. For instance, independent homebuilders may be reluctant to buy lots because of the competition from the developer’s own building activities, especially in light of the developer’s cost advantage and presumed asymmetrical knowledge. The problem of building on some lots and selling others can be alleviated by bringing in builders who will target their product to a different market segment and by coordinating their activities to achieve a harmonious aesthetic and well-tailored mix of product.

Customs vary in different regions when it comes to developing small residential subdivisions. In some areas, it is typical for homebuilders to subdivide the land and build the houses together, using a single construction loan—especially for tract houses in communities that require public hearings on house plans and on lot subdivision.4 It is also possible that lenders may prefer to underwrite these activities separately, given their different risk profiles and collateralization.

In general, land development is riskier but more profitable than homebuilding because it is dependent on the public sector for approvals and infrastructure and involves a long investment period with no positive cash flow. Assuming this combination of risk and investment must be rewarded by the market.

Although opportunities exist for many types of land, beginning land developers are advised to search for comparatively problem-free tracts of land: land that is already served by utilities and is appropriately zoned or requires only administrative public approvals. Although raw land may be available, the resources and the time required to entitle and bring utilities to a tract are beyond the capabilities of beginning developers. Time and money are better spent building a track record of successful small projects.

Market analysis occurs twice during land development—before site selection and after site selection, as the project is better defined. The objective of market analysis before site selection is to identify which segments of the market are underserved and which sorts of buyers might be lured by a competitively priced and appropriately designed development. Large developers have the luxury of investigating a number of markets, even internationally, to select the most competitive product type and location. Beginners lack the resources required for such an exploration. In addition, they usually want to remain close to home, in familiar territory with personal connections. If possible, their projects should be near enough for them to keep a close watch over on-site progress. Further, local planning bodies and regulatory agencies tend to view local developers less suspiciously than they might view out-of-towners.

This is not to say that more distant opportunities should not be considered, but beginning developers have enough difficulties to overcome without the additional hurdles of distance and unfamiliar markets, officials, and building practices. Moreover, beginning developers’ primary concern, aside from developing stable cash flow, should be the cultivation of their reputation, which is easier with multiple projects in one market.

A developer’s primary market decisions concern the proposed project’s use, location, and size. Use preferences might arise from market conditions, such as a perceived shortage in one type of housing or commercial space or from construction expertise in a particular type or scale, which may offer functional or price advantages versus the market. If a developer has no preference for a specific use, then each segment of the market—residential, industrial, commercial, or mixed-use—should be analyzed. Real estate markets are highly segmented, and a developer cannot infer from the demand for residential development that retail development is also in demand (see chapter 1 for an overview of market cycles by type). Similarly, a developer should not assume that demand for the same product extends across multiple submarkets.

It used to be common practice for a developer to select a use and a target market and then find a suitable parcel of land. Today, with developable sites at a premium in so many metropolitan regions, it is common to select the site first, possibly even “tie it up,” and then undertake market analyses to identify potential uses and markets for that parcel. If the developer has already identified the land use for which excess demand exists, the purpose of the market analysis is to identify the particular market segment (for instance, “midpriced, single-family houses for move-up families”) and the location where demand is greatest. This formulation simplifies the task, though, because for most developers, mitigating market risk means pursuing multiple potential markets at once, often in the same community.

The master-planned Biltmore Park Town Square combines retail and office space, a hotel, and a variety of residential types on a 57-acre (23 ha) site.

SHOOK KELLEY

Major sources of information are brokers, lenders, and, in particular, builders to whom the land developer will market the developed sites. Because developers and homebuilders are prospective clients, they are usually eager to provide assistance. Some caution is advised, however, because some of these builder-clients will also be competitors. It is also possible to obtain relevant market information at little cost from other sources. Major lenders, market research firms, and brokers often publish quarterly or annual reports for apartments, office space, single-family houses, and industrial space. A wealth of economic and market information can also be found on the Internet, particularly in the case of for-sale housing, which is served by the Multiple Listing Service and other private market reporting services. Assembling this information and analyzing it can take considerable effort, even at the early stages, so it may be more efficient to hire a market consultant. The most important questions to be answered concern the market for the proposed product type:

• Where are the most desirable areas or parts of town?

• What are the hottest segments of the market?

• Who are the most active buyers? What are their characteristics and preferences?

• Are there competitors other than new subdivisions (that is, renovations, conversions)?

• If a builder owned land in that area, what would he build?

• For what types of building are lenders giving loans?

• For what types of building are lenders not giving loans?

• Where are building permits being issued? What kinds of permits are they?

• What physical features and amenities are especially popular?

• Are amenities built into the sale price or are they fee supported?

• Who are the main builders? Are they producing custom, semicustom, or tract home products?

• Who else is developing in a particular area? What are they building? How many units (or square feet) are planned or in the approvals pipeline for the future?

• How many units are they selling per month, and how long at this pace?

• What are the standard deal terms that builders are using to buy lots?

• Are other developers subordinating lot prices, financing construction, or offering other hidden subsidies?

Major homebuilders project the annual demand for units by price category throughout their metropolitan area. They break down the number of houses sold in each market area of the metropolitan region by $25,000 or $50,000 intervals. For example, suppose it is estimated that 56 percent of all new housing units will be sold in the western part of town and that 75 percent of the units will be priced under $300,000. If the total projected demand for the city is, say, 500 houses in 2012, the demand for houses costing under $300,000 in the western section of town would be 210 units (56 percent × 75 percent × 500).

After estimating demand, developers should ask how much of that demand can be captured by their project. Irrationally exuberant capture rate projections are among the most common pitfalls of even experienced developers. This calculation should be based on extremely conservative assumptions, and the correct answer depends on the number of similar projects selling in the market, and on how competitive the proposed development is likely to be. Developers must consider whether their site is less physically attractive or accessible or features the same level of amenities as the competition. Suppose a given area contains 2,100 lots in 20 subdivisions. If each of four developers has five of the subdivisions, each developer’s share of the market captured would be 25 percent, or 525 lots (25 percent × 2,100). Many developers allocate more lots to subdivisions that possess better amenities, terrain, or management. They also look at historical absorption rates by different subdivisions and developers. Depending on the weight given to each factor, the analysis indicates that the developers should capture more or less than their prorated share. If they anticipate selling twice their share, however, then the other developers must theoretically lose market share by the same amount. In the short run, builders can steal market share from other builders, if they have a better design, amenity package, or location. In the long run, however, builders who are losing sales will cut prices or increase marketing, incentives, or amenities until they regain their share.

Land developers must remember that their product is an intermediate good used for an end product. The demand for finished lots depends on the demand for houses—not just for any houses but for houses in the price range that justifies the lot price. If demand for those houses declines, so will the demand for lots.

The ratio of lot price to house price has risen since the 1960s and may vary from about 20 to 50 percent. Higher ratios may be found in areas such as infill sites in high-income cities and suburbs and in high-priced metropolitan areas like Los Angeles, San Francisco, Washington, D.C., and Boston. A general rule of thumb is that builders pay approximately 25 percent of the finished house price for the lot. Thus, if they build houses that sell for $200,000, they can afford to pay $50,000 for the lot. Developers should not, however, rely on rules of thumb but should carefully investigate local market conditions. A rule of thumb can be useful to quickly understand the economics of a particular land purchase. If a particular parcel’s price, zoning, and development costs would break even at $75,000 per lot, the developer may conclude that this deal has a low likelihood of success as currently envisioned.5

Suppose the absorption rate is ten units per month for $200,000 houses, compared with 15 units per month for $160,000 houses. Builders of the $200,000 houses will pay $50,000 per lot rather than $40,000 per lot for the less costly houses. If developers proceed with their projects under the assumption that they can sell $50,000 lots, they may be in trouble if the market turns out to favor the less expensive houses. Even if they are willing to accept the lower sale price of $40,000 per lot, their lenders may set loan covenants that prevent—or at least delay—the sale.6

Market research is a critical first step, not only for selecting a site but also for assembling a list of builders to approach. Another benefit of the preliminary market analysis is that even while looking for sites, the developer can generate interest among builders. One might focus on smaller builders who build five to 50 houses per year, and who are likely to purchase a few lots at a time in a subdivision. The builders will tell the developer where they want to build and what the ideal lot size, configuration, and amenity package are. If the developer can meet their requirements, builders may even precommit to purchasing the lots by a letter of intent. Such commitments, while seldom legally binding, can be the linchpin of the developer’s first deal. A firm purchase letter from a creditworthy builder can give the beginner the credibility needed to obtain financing.

In selecting a site, beginning developers face a number of limitations that can be overcome only with diligent research. To overcome the limitations,

• choose a manageable geographic area for the search; a good guideline is “no air travel”;

• set an appropriate time frame for investigating market conditions;

• do not depend exclusively on brokers to find sites; and

• do not look for “home runs”; build a reputation on singles and doubles.

Site Evaluation Factors

MARKET AREA AND COMPETITION

• Existing inventory

• Pipeline

• Similar products that may compete

• Meaningful price points

LOCATION AND NEIGHBORHOOD

• Proximity to key metro locations

• Quality of surrounding environment

• Existing housing stock, other buildings

• Schools and churches

• Parks, clubs, and recreational facilities

• Other amenities

• Shopping and entertainment

• Public improvements (existing and planned)

UTILITIES

• Water and sewer/septic

• Electricity (availability and quality)

• Teledata/broadband/cable TV

• Wireless reception

PHYSICAL CONDITIONS

• Visibility and accessibility

• Slopes and required grading

• Vegetation, forestry, and agriculture

• Existing structures

• Soils and hydrology

• Toxic wastes and nuisances

• Wildlife and ecological features

LEGAL CONSTRAINTS

• Utility and private easements

• Covenants and deed restrictions

REGULATORY ENVIRONMENT

• General climate toward development

• Exactions and impact fees

• Future infrastructure work/takings

• Approval process and timeline

• Methods of citizen participation

• Administrative vs. board approvals

• Upcoming elections and rule changes

Because beginners lack reputation and contacts, they are less likely to hear about deals firsthand. But deals that have been “on the street” are not necessarily bad deals. A property may have been passed over for many reasons: the site may be too small or otherwise uneconomical for a large firm but may be suitable for the beginner. In addition to working with a network of brokers, developers should not be afraid to talk to landowners whose land is not currently for sale. Direct contact may generate a deal or lead to a possible joint venture or favorable terms of purchase. Large landowners know one another, and even a “no” may eventually lead to a referral.

SITE EVALUATION. The relative importance of various factors of subdivision development depends on the end user of the lots. The major site evaluation factors are summarized in the accompanying feature box, and greater detail regarding site evaluation for residential development can be found in chapter 4.

Many physical, legal, and other factors must be considered before buying a site. Among the more important items, the developer should

• make sure all easements are plotted on a map and that any easement problems are cleared up and any purchase arrangements for easements made before closing;

• check for drainage problems and ascertain the level of the water table, which affects sewer lines, septic tanks, and building foundations;

• check seismic hazard maps to make sure that faults do not cross the land;

• check flood insurance and Flood Hazard Area maps;

• check Federal Housing Administration (FHA) requirements concerning width of roads, culs-de-sac, and other design requirements;

• investigate whether any parties are likely to delay or stop the sale; pay particular interest to seller’s family;

• make sure that utilities such as water, sewer, gas, electricity, and communication lines are available;

• check with planning/zoning and engineering departments about off-site requirements;

• check permit costs, impact fees, and exactions, and consider statutory accelerations or upcoming changes;

• check for appropriate zoning and research actual—not statutory—approval timelines for similar projects;

• determine whether all necessary development approvals will be granted, or make closing contingent on approval;

• make sure that builders will be able to obtain building permits in a timely fashion;

• check for environmental issues—especially if a body of water lies on the land; avoid wetlands, as they usually involve a time-consuming approval process;

• beware of unusual soil chemistry or composition, such as sulfates or high clay levels;

• check for radon, a harmful derivative of uranium that is present in many areas;

• check historical aerial photos that may show evidence of toxic waste, such as storage tanks on the site;

• check construction lenders’ requirements for environmental site assessments;

• check for landfills and other nuisance-generating sites close by, including informal or illegal sites;

• look for smoke, fumes, or odors, and check the land at all times of the day; and

• always walk the land.

Adams & Central in south Los Angeles combines 80 units of mixed-income housing with a street-level grocery store and other shops, and underground parking.

WAYNE THOM PHOTOGRAPHER

The developer should also carefully consider the surrounding environment. What is the overall political climate? Will the community object to new development or does it support growth? Is the planned development compatible with the surrounding neighborhood or with approved comprehensive plan goals? If so, is the plan up for review soon? Are shopping, schools, and parks nearby? If schools are an issue for the project, what is their reputation and in what direction is that reputation moving?

SITE ACQUISITION. In land development, as in other forms of development, a three-stage contract is customary: a free-look period, a period during which earnest money is forfeitable, and closing. This point of negotiation is as important as price: purchasers want as much time as they can to close with as little money at risk as possible. Sellers want the reverse: for the closing to occur as quickly as possible with as much forfeitable earnest money at stake as possible. The agreed-on terms depend on the state of the market and can change rapidly.

In slow markets, favorable terms of purchase are more likely. With fewer buyers, sellers are typically more willing to give a potential purchaser more time to investigate the property without requiring hard earnest money. In a hot market, sellers are less afraid of losing any particular deal and are more concerned about tying up their property when another buyer, and possibly a better offer, may be just around the corner. As conditions in the marketplace shift toward seller-dictated terms (requiring cash offers without financing contingencies, short due diligence periods, and high prices), the market is likely nearing its apex, so the beginning developer who is having trouble competing as a buyer may just be better off waiting.

If the site consists of multiple parcels under separate ownership, progress is further complicated by the fact that all the necessary parcels must first be acquired. Land assembly is a tricky business and usually requires sophisticated negotiation and acquisition techniques to ensure that the owner of the last or other key parcels does not insist on an exorbitant price.

The terms of acquisition set the stage for everything else, and an overpriced or complicated takedown of land can doom an otherwise well-conceived project. When buying land, developers are chiefly concerned about whether or not they can build what they want, whether they have time to study all site conditions affecting feasibility, and whether they will be able to assemble market data, obtain financing, and assess project economics in a business plan before the required closing.

Sites with special problems, such as easements or contamination, may prove attractive but must be approached with caution because they may be more difficult than a beginner can handle. Beginning developers are usually thinly capitalized, leaving little room for unanticipated costs or delays. Before deciding to tackle problem sites, beginning developers must determine whether the problem can be solved within a reasonable time frame and cost. If they cannot answer that question affirmatively with a high level of confidence, they should probably look for another site.

Because of possible legal complications, developers generally use an attorney during land acquisition, no matter how straightforward a transaction might appear to be. Each part of the country has its own terminology for the sequence of steps in property acquisition. In Texas, for example, the first step is called signing the earnest money contract; in California, it is going into escrow on the purchase contract; and in Massachusetts, the initial offer is an offer to purchase agreement. In most cases, these actions initiate a free-look period during which various contingencies have to be resolved. This agreement is binding and contains all the contingencies, at least in summary form. It stipulates that on or before a certain date, the parties will enter into a purchase and sale agreement, which enumerates and records all aspects of the transaction.7

Even before submitting a purchase contract, purchasers may discuss or submit a letter of intent or term sheet to sellers that sets out the business terms for purchase of the property. The letter of intent specifies the property to be purchased, its price, payment terms, timing, release provisions (for transfer of lien-free subparcels, in the case of seller financing, to the buyer), and other major business points. Letters of intent are especially helpful when the purchaser or seller plans to use a long, specially written legal purchase agreement rather than a standardized broker’s form. The letter of intent saves time and unnecessary legal expense in the beginning because it clarifies the primary aspects of the transaction. If the buyer and seller cannot come to agreement on the major business terms, there is no point in exchanging full legal documents. The letter of intent is nonbinding, but it does call for signatures by both parties to signify agreement on the major transaction points.

The offer to purchase must spell out all contingencies and any penalties other than specific performance (compelling the parties to consummate the agreed deal) for failure to close. They typically include physical inspections, environmental assessments, regulatory approvals, title checks, and/or financing approval. A common mistake is for purchasers to assume they can negotiate more contingencies or other issues in the purchase and sale agreement. The latter cannot be more restrictive than the offer to purchase unless both parties agree to the changes. Three items make the offer to purchase binding: (1) specific consideration, enough to entice the seller to take the property off the market for a given period; (2) proper identification of the property; and (3) a time to close or to enter into the purchase and sale agreement. The offer to purchase should include a provision for return of the purchaser’s deposit if a purchase and sale agreement is not signed.8

Steps for Site Acquisition

BEFORE OFFER

1. Verify that a market for the property type exists.

2. Determine the price you can pay by running preliminary financial pro formas.

3. Determine whether or not the seller can sell the property for the price you want to pay. (Estimate the seller’s basis and outstanding mortgages on the property.)

4. Find out why the seller is selling the property. (Is the sale necessary, or can the seller wait for a better price?)

5. Check the market for comparable properties in the area and their prices over a multiyear period.

OFFER

1. Ask for at least 60 days for due diligence. If a broker brought the developer the deal, the developer might expect that the broker also contacted four or five other developers and that 60 days for due diligence may therefore not be acceptable to the seller.

2. Place a refundable deposit, or earnest money. Customary percentages vary widely by region and by deal size.

3. Request specific due diligence that must be provided by the seller, such as surveys, soils reports, hazardous waste clearances and certifications, preliminary design and engineering studies, preapproved plans, development rights determinations, or agency approvals.

4. Negotiate terms and fees for unilateral extension of closing (monthly fee, number of months available).

DUE DILIGENCE

1. If zoning must be changed for the project, ask for closing to be contingent on zoning approvals; if it is not approved, the earnest money is refunded. Be sure to state in the offer exactly what constitutes approval, for example,

• general plan approval;

• rezoning approval;

• conditional use permits (variances or waivers);

• development agreements;

• tentative tract or parcel map;

• final tract or parcel map;

• grading plan approval;

• site plan approval;

• design approval; and

• building or disturbance permits.

2. Answer other questions:

• Can a good title be secured?

• How much of the site is buildable, how soon? What are the existing leases, easements, slopes, soils, floodplain, drainage, and geological conditions?

• Can you build what you want to? How many units, of what size and at what density, can be built? Can parking and amenities be built?

• Can financing be obtained not only for land but also for the improvements you envision?

3. Accomplish the following before closing on the land:

• preliminary design drawings;

• conceptual estimate of construction costs;

• mortgage package preparation;

• commitment from permanent lenders;

• commitment from construction lenders;

• receipt of regulatory approvals or assurances that they can be obtained (zoning opinion or development rights determination); and

• selection of construction manager and property manager (who should assist in designing the project).

4. If more time is needed, ask for it. If the seller refuses, ask for the deposit money back and pull out of the deal.

CLOSING

1. Closing typically occurs 60 days after due diligence is complete, although longer periods can often be negotiated.

2. Closing can be made dependent on a variety of factors, including the availability of financing and the removal of toxic wastes.

Purchase Contract or Earnest Money Contract. Whether or not a letter of intent is used initially, the purchase contract (also called purchase and sale agreement or earnest money contract) is the primary legal document for purchase of property. It sets out all terms of purchase, indemnities, responsibilities for delivering title reports (usually the seller) and other documents, performing due diligence, and remedies in the event that the sale does not close. Signing the final purchase agreement may happen immediately in the case of a simple purchase contract for one or several lots, or it may drag on for weeks or even longer if buyers and sellers haggle over individual provisions. Although purchase contracts are almost always negotiated following due diligence, the purchaser may use the time delay in signing to begin to line up financing, to recruit builders, or to advance project design. Until the purchase contract is signed, however, the buyer is at risk of the seller’s accepting another offer. Complicated purchase contracts are appropriate in complex transactions of larger properties, but beginning developers should keep it simple. Overly complicated legal paperwork may signal the seller that the buyer is litigious and vice versa.

Contingencies. Contingencies in the purchase contract refer to events that must occur before the purchaser “goes hard” on the earnest money. Beginning developers often make the mistake of including many unnecessary contingency clauses that only complicate the negotiations. The most all-encompassing clause is one that makes the sale “subject to obtaining financing.” If, for whatever reason, financing is not available, then earnest money is returned. Another encompassing clause is “subject to buyer’s acceptance of feasibility studies.” The contract may spell out those studies to include soils, title, marketing, site planning, and economic feasibility. As long as the clause gives the buyer discretion to approve the reports, it effectively gives the buyer a way out of the contract. As soon as the buyer goes hard, though, he is subject to forfeiting the earnest money paid to the seller if the sale is not completed.

Most sellers will not give a blanket contingency for more than 30 to 60 days. Local market conditions determine whether sellers will give buyers a free-look period.

An important contingency in the purchase agreement is that the seller must support the developer in obtaining zoning and other necessary approvals. In areas where extensive public approvals make the allowable building density uncertain, some developers purchase sites on the basis of the number of units approved. In this case, the seller has a strong incentive to assist in the approval process. For example, if the price is $50,000 per unit and permission is given to build 100 units on the site, then the purchase price would be $5 million. If the developer receives approval for only 80 units, the price would be $4 million. Having the seller on the developers’ side can be valuable in a tough approvals environment, where developers may have less credibility than longtime landowners.

As a general rule, 3 to 5 percent of the total purchase price or a payment of $25,000 to $50,000 for smaller deals is required as earnest money for a 90- to 120-day closing. Because the earnest money theoretically compensates the seller for holding the property off the market, the earnest money usually bears some relation to the seller’s holding cost or the opportunity cost of risk-free interest on the sale price. The amount is negotiable but has to be large enough so that the seller believes that the buyer is viable and serious about closing. Financing land is expensive—usually at least two points (2 percent) over prime. For example, if the prime rate is 10 percent and the land loan is 12 percent, then a four-month closing would incur holding costs of 4 percent (4/12 × 12 percent).

In hot markets, sellers may sometimes try to get out of a sale because they have received a higher offer. Although each state has its own property law, buyers generally control a purchase contract as long as they strictly observe its terms. Most contracts state that a clause is waived if the buyer does not raise concerns in writing before the expiration date of the clause or contingency. If the clause (such as buyer’s approval of title reports) is not automatically waived according to the contract, however, the seller may argue that the buyer failed to perform in a timely fashion and that the contract is therefore null and void. If the seller tries to get out of the contract before the expiration date, the threat of litigation is usually sufficient to bring the seller back to the table. Pending litigation makes it very difficult to sell the property to anyone else and can tie up a property; it is a last resort on the part of the buyer.

Release Provisions on Purchase Money Notes. One of the most important areas of negotiation concerns the release provisions on purchase money notes (PMNs)—seller financing used to purchase the property (also called land notes). Release provisions refer to the process by which developers remove and unencumber individual parcels in larger tracts from the sellers’ land notes. Release provisions are also a major part of the negotiation with the developers’ lenders (discussed in “Financing” below).

Lenders require a first lien on the developer’s property. Lien priorities are determined strictly by the date that a mortgage is created. Thus, land notes automatically have first lien position, unless sellers specifically subordinate land notes to land development loans, which they almost certainly will not. Developers must release land from the land note before they can obtain development financing from lenders. The unencumbered land constitutes their equity. Even if developers finance development costs out of their own pockets, land must be released from the land note for the developer to deliver clear title to builders or other buyers of the lots. Buyers need clear title (free of liens) before they can obtain their own construction financing. Buyers usually view land note financing favorably during the predevelopment period before they take down the construction loan, as long as they have the option of paying it off at any time.

Land sellers’ main economic concern is that they will be left holding a note with inadequate underlying security. As landowners, they also do not wish to have a large property fragmented by a failed development. They therefore want strict release provisions that require the developer to pay down more on the land note than the actual value of the land to be released, leaving more land as security for the unpaid portion of the note. Additionally, they wish to preserve their un-released parcels in a contiguous piece. The developer’s objective, on the other hand, is to achieve maximum flexibility in the location and acreage of land to be released. Ideally, the developer wants to be able to release the maximum amount of land for the minimum amount of money, but this flexibility is particularly important early in the project’s life, when costs have exhausted a large proportion of the developer’s capital, and positive cash flow is critically important.

Suppose a developer purchases 100 acres (40 ha) for $1 million with an eight-year land note for $800,000, or $8,000 per acre ($20,000/ha). The note is amortized at the rate of $100,000 per year. Suppose the developer also negotiates a partial release provision that calls for a payment of $12,000 per acre ($30,000/ha). If the developer wants to sell 25 acres (10 ha) to a builder, then he must pay the seller $300,000 (25 × $12,000 or 10 × $30,000) to release the land. Without carefully worded language, the developer’s $300,000 payment reduces the seller’s note from $800,000 to $500,000. Instead of reducing the note principal balance immediately, the special language permits the developer to pay interest only on the note for the next three years. A clause “all prepayments are credited toward the next principal installments coming due” means that the next three principal installments are paid by the $300,000 payment, but that repayment of the note is not accelerated. The developer will not have to make another principal payment for three years. Without the language in the clause, the seller would probably construe that the $300,000 payment simply shortens the remaining life of the note from eight to five years. The developer, of course, wants the flexibility of the full term, so that it will not be necessary to sell the land prematurely or to find other financing sources to pay off the land note. It is increasingly common for release payments to be negotiated as a simple percentage of net sale price, subject to review against developers’ initial representations of lot pricing, but the principle still holds.

Tips for Land Acquisition

Conversations with a variety of successful developers have produced a number of useful tips regarding land acquisition.

• Make sure the owner is willing to sell the land. Sellers may use your bids to negotiate with others.

• Do not let the seller dictate the use of the property after the sale.

• Beware of appraisals of sites that have not been physically analyzed for hazardous or other undesirable conditions.

• When rezoning is necessary, attempt to buy the land on a per-unit basis, giving the landowner an incentive to help obtain approvals.

• If a conditional use permit or variance will be needed, ask the current owner to sign a waiver to allow you to act as his or her agent in dealing with the city or county before closing.

• If you obtain seller financing, make sure the seller frees up some of the land immediately so that you can build on it. You need to be able to give the construction lender a first lien on the land.

• In some states, such as California, you should use a deed of trust for purchase money mortgages so that the seller cannot claim a deficiency judgment against you if you default.

• Concerning “no-waste” clauses, be sure to read the fine print on the trust deed form because you may not be able to remove trees or buildings on the property until the note is paid off.

• Make sure you select a title company that is strong enough to back you up if you need to defend a lawsuit involving title. Some nationwide title companies enfranchise their local offices separately so that you do not have the backing of the national company.

• Make sure that the seller’s warranties survive the close of escrow. Consult your attorney for the current state law on this topic.

• Beware of broker commissions. A broker who casually mentions a property as you drive by it may try to collect a commission if you later buy it.

Developers never want to release more land from the note than is necessary at any one time, because seller financing is usually their lowest-cost source of money. Thus, they should try to avoid release provisions that call for releasing land in strips or contiguous properties.9 If releases must occur on contiguous properties, developers would be forced to release the entire property to develop or sell a tract at one end. Sellers will rightfully be concerned if developers can “cherry-pick” the most desirable land and then abandon the rest of the project. To get around this problem, the release provision can assign values to parcels or strips in the property that reflect market values. Thus, prime land may have a release price that is significantly higher than that for less desirable land. Alternatively, the provision may call for the developer to release two acres (0.8 ha) of less desirable land for every acre (0.4 ha) of desirable land, or the release may be spelled out in a predetermined sequence of parcels coinciding with the phasing plan of the development. In short, a variety of structures can be employed to assuage sellers’ concerns, but developers must maintain the ability, within reason, to change direction.

KEY POINTS OF A PURCHASE CONTRACT. A variety of clauses and provisions should be included as part of the initial purchase contract to minimize later renegotiations with the seller:10

• Supplementary Note Procedure—This clause allows the sale of subparcels (parcels within the original tract) to builders and other developers without paying off the underlying first lien. This provision, which must be specifically negotiated, allows the developer to pass on seller financing to builders through a supplementary note, which gives builders more time before they need to pay the full lot cost. Nevertheless, unless the seller is willing to subordinate seller financing, the supplementary note has first lien position, which means that builders who purchase subparcels must pay off the note before they can obtain construction financing, as construction lenders also require a first lien position. In fact, builders usually pay off the supplementary note with the first draw on the construction loan.

• Out-of-Sequence Releases—This clause satisfies the developer’s need to release certain parcels out of sequence for major utilities or amenities.

• Joinder and Subordination—This clause provides for the seller to join within 30 days any applications for government approvals made by the developer. It also provides for the seller’s subordination agreements, required by any government authority for the filing of subdivision maps or street dedications.

• Transferability—This clause protects the seller from having the deal he has negotiated transferred to another buyer, presumably giving the buyer the benefit of any appreciation added value. Nontransferable contracts may give the seller unreasonable influence if the buyer needs to bring in a partner later.

• Subordination of Subparcels—Most sellers are unlikely to allow subordination of their note to development lenders. They may be willing, however, to allow subordination on one or two subparcels. This action can help the developer obtain the development loan without paying off the land note.

• Seller’s “Comfort Language”—The seller is not required to execute any documents until he or she has approved the purchaser’s general land use plan.

• Ability to Extend Closing—This clause permits the purchaser to extend the closing by 30 or 60 days by paying additional earnest money.

• Letters of Credit as Earnest Money—The developer can greatly reduce upfront cash requirements if the seller will accept letters of credit as earnest money. Letters of credit can be cashed by the seller on a certain date or if certain events occur, such as a purchaser’s failure to close. For example, this type of clause might say, “Purchaser may extend the closing for 60 days by depositing an additional $50,000 letter of credit as additional escrow deposit.”

• Property Taxes—Many municipalities and counties have categories such as open space or agricultural land that give the owner a reduction in taxes. When the land is developed, the owner must repay the tax savings for the previous three or five years. This assessment, commonly known as “rollback,” can amount to a major unexpected cost to the developer if it is not provided for in the purchase agreement. For example, such a provision might say, “Seller agrees to pay all ad valorem tax assessments or penalties assessed for any period before the closing as a result of any change in ownership or usage of the property.” In addition, some areas with agricultural-use taxation will only guarantee these favorable tax rates to landowners who enroll their parcels in voluntary restrictive use agreements. These agreements can run five or ten years, and since they are not easements, they will not necessarily be visible in the recorded history of the parcel deed.

• Title Insurance—The seller usually (though not always) pays the title insurance policy. Many title insurance policies have standard exception clauses, however, such as a survey exception.11 The party responsible for paying the insurance premium for deleting these exceptions is subject to negotiation.

• Seller’s Remedy—If the purchaser defaults, the seller’s sole remedy is to receive the escrow deposit as liquidated damages. This clause prevents the seller from pursuing the purchaser for more money if the sale falls through.

These clauses constitute only a small fraction of all those included in a standard purchase contract. They are highlighted here because they represent items that the purchaser should try to negotiate with the seller. Experienced developers use a specially prepared standard form that includes such clauses. Sophisticated sellers may insist on using their own custom contract, to which these clauses will probably have to be added. An experienced real estate attorney should always assist in the preparation of contracts.

After tying up a site, the developer should reexamine the target market for the proposed project. Special features of the selected site, as well as changes to the overall economic climate, may indicate a different market from the one identified during the preliminary market analysis undertaken before site selection. Land uses change slowly, but markets can change quickly.

At this stage, analysis should concentrate on location, neighborhood, and amenities. For example, suppose a developer’s initial target market is buyers of move-up houses selling from $350,000 to $400,000. If sales in that price range are moving steadily, the developer may want to continue with such a program, even if several other developers are competing at the same price point. But if the developer has found that market to be saturated, with forward indicators such as building permits or presale deposits beginning to soften, he may modify plans and develop a lower-priced community. Alternately, a more upscale product that is not represented in the market may be appropriate if demographics and market prove favorable. Developer Dan Kassel cautions, “When you’re selling ‘home,’ you can’t help having your own ideas about that word, a vision of what it might mean, but you must absolutely subordinate your personal vision to what you can learn about your customer.”12

The market analysis at this stage helps the developer

• advance physical planning: market data help determine the specific target market and therefore the size and configuration of lots, amenities, and other fundamental aspects of the design;

• compile the appropriate documentation (for example, a development appraisal) to obtain a loan and refine a business plan for investors; and

• attract builders and partners: a credible market study and statistical backup will be essential in communicating the value of the proposed community.

Unless a subdivision is very small or the developer has already secured informal commitments from builders, a local market research firm that specializes in subdivision development should be hired. Ideally, the market research firm should already have a database covering all the competing subdivisions. From its analysis, the market research firm should be able to assist the developer in determining the best market for the lots, and the total number of lots that the developer can sell per month, grouped by lot size and price range. The report should document total housing demand and supply for the market area and, from that number, project demand and supply for the specific product type and submarket area the developer’s project will serve (see feature box on page 86). The bottom line of the market study should be a projection of the number of units that can be sold each month by product type and the projected sale price. For example, suppose demand for $200,000 to $250,000 townhouses is 200 houses per year (16 per month) in the submarket and two subdivisions are competing for buyers. Expected sales would be approximately five per month, assuming that each subdivision captures its share of total demand. However, this figure should never be assumed to be the pace of sales. Demand is never totally met by product that is actually developed. Many potential buyers will not purchase what is offered because it is too expensive, it is not to their taste, or any number of other reasons. Projections of the pace of sales must always be tempered by observation of market reality. Regardless of what demand statistics show, if other developers of similar projects in the general area are selling only two or three units per month, it is unlikely that anyone—particularly a newcomer—will sell twice as many. Developed lots are an intermediate factor, not the only factor, in the production of housing. Although a shortage of housing may exist, a surplus of lots may also exist. Therefore, the market study should examine demand and supply for both the final housing product and developed lots.

Generally, a homebuilder purchases (takes down) more than one lot at a time. A lot sale may include four or five, or as many as 100 lots, depending on the type of project, size of builder, and market conditions. Rolling options are a popular method for master developers to control builders’ takedown of lots. These options provide for the builder to take down a designated number of lots every quarter or year. The option gives the builder an assured supply of lots, at a predictable wholesale price, while giving the land developer an out from the contract with the builder if he cannot sell as many houses as anticipated. The rolling option typically has a built-in price escalation in the lot price—perhaps a 2 to 4 percent increase per year. Rolling options can be structured to protect the interest of the master developer, the builder, or both.13 The master developer wants to have some assurance that the builder will meet or exceed the takedown schedule and that he cannot tie up future option increments if he is not performing. The builder wants to ensure continued availability of lots—but does not want to pay before he needs them. He wants to carry as small an inventory of lots as possible and wants the ability to decline future options with as little notice or penalty as possible.

The builder may pay option fees, which are usually based on the value of the unexercised options. Paying option fees is a tradeoff against a reduction in the price escalation: If option fees are paid, the price escalation is lower. Higher option fees are a technique to encourage the builder to take down the option sooner (to avoid paying the option fee). Option fees are paid even if the future increments are not acquired. For example, suppose a master developer has 200 lots. The deal may provide that the builder has an option to purchase annual increments of 50 lots over a four-year period. If the builder fails to take down any scheduled increment, he may lose his option rights to all future increments. The builder can exercise his options more quickly and will pay value escalations and/or option fees on unexercised options. Incentives other than cash may be attractive to builders. If the community is unique, access to custom-home clients through an “approved builder” list may be an attractive incentive, or simply favorable land subordination deals may more effectively address builders’ risk than option pricing.

What Makes a Good Market Study

PROPER DELINEATION OF THE MARKET AREA

The geographic area where competing subdivisions are sampled should be large enough to include the entire quadrant of the city where your project is located, but small enough to exclude areas that derive their economic value from proximities the subject site does not share.

PROPER DELINEATION OF THE COMPETING MARKET PRODUCT TYPES

A market should not be defined so narrowly that it omits relevant competition, which leads to underestimated supply. For example, low-cost single-family houses compete with condominiums for buyers.

THE CAPTURE RATE

The capture rate of lots for the subdivision should take into account both the total demand in the marketplace and the number of other subdivisions. In metropolitan areas with populations greater than 1 million, capture rates in excess of 5 percent for any project, are suspect. Capture rates greater than 30 percent may be appropriate for very specialized products (which should connote a small overall market as well), or within a severely supply-constrained market. The case for a supply-constrained market must also look at the development pipeline.

EMPLOYMENT AND ABSORPTION RATES

Projections of demand should be based both on employment projections and on historic absorption rates in the area. Large increases relative to historic absorption rates are always suspect.

A project’s feasibility is affected by regulations from the local, state, and federal levels. It is important to understand these regulations and be able to navigate the approval process efficiently. The developer’s goal should be to reduce risk at every step in the process.

ZONING AND PLATTING. The process of subdividing land is called platting or mapping. Platting usually involves a zoning change, typically from a low-density designation to a density one or two steps up the zoning spectrum. In suburban fringes, land is often zoned agriculture or some other nearly nondevelopable designation that must be rezoned to allow lot subdivision and development. Every locality has a different procedure for zoning,14 though there are common elements. In the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic, zoning is administered at the township level, or by the city in urban areas. In the South and West, the process is driven by county or municipal government. Vast differences in the professionalism of staff and officials exist among jurisdictions. Rezoning applications are formal proposals to the regulatory agency, typically an appointed planning commission, to modify the jurisdiction’s zoning map to allow a different use or greater density on specific parcels. The applicant must make the case that the proposed changes, though not consistent with the existing map, are consistent with goals of the jurisdiction’s comprehensive plan and are beneficial, or at least not detrimental, to the infrastructural and fiscal environment. In reality, the process is politically fraught, and the topics of discussion are likely to be concerns of abutters, ranging from traffic to property values to noise and other nuisances, as well as larger issues of urban structure and infrastructure.

The process can take from several months to many years, depending on the environmental and political sensitivity of the site. Many sites are also subject to the approval of special agencies or commissions, which adds costs and time. For example, land in California that is located within 1,000 yards (915 m) of the ocean is subject to the California Coastal Commission’s jurisdiction. Fulfilling the commission’s requirements may add years to the time necessary to secure subdivision approvals. Because even many experienced developers lack the staying power to pilot a site through the commission’s process, beginning developers are well advised to avoid situations that involve lengthy and expensive approval processes.

Platting Process. Platting is the official procedure by which land is subdivided into smaller legal entities. It is the means by which cities and counties enforce standards for streets and lots and record new lot descriptions in subdivisions. The legal description of a house lot typically follows this form: “Lot 10 of Block 7143 of Fondren Southwest III Subdivision, Harris County, Texas.” The legal description parallels the platting procedure. The developer submits a plat of the property showing individual blocks and lots. In some areas, platting requires a public hearing, even if the intended use conforms to the zoning. In other areas, no public hearing is required as long as the platted lots are consistent with zoning and all other subdivision regulations. Even when platting is legally an administrative process, the developer may find himself drawn into a public process by companion ordinances to the subdivision law, such as water protection or critical slope protections.

The number of units permitted to be built on a given parcel usually depends on a combination of several factors, including minimum lot width and depth, setbacks, alley requirements, and street rights-of-way. The target market determines whether a developer plats the greatest possible number of lots, creates larger lots for more expensive houses, or includes a mix of types. A developer should avoid going for the highest allowable density unless previous experience has shown that the resulting density and smaller lots are consistent with target market demand. With that in mind, it is fairly common for developers to enter the process proposing density near the maximum allowable, knowing that the process will almost always result in a reduction from the initial proposal. In areas with transferable development rights (TDRs), this action can have additional benefits, as the developer may be able to monetize any surplus of rights beyond his business plan by selling them to other developers on the TDR market. Even in areas without formal TDRs, tax-funded conservation can compensate developers for entitled, but unused, developable lots. Both processes are complex legal arrangements, and a land use attorney should be consulted before acquisition to ensure that the development’s structure allows these kinds of transactions.

Replatting a previously platted area can present unexpected difficulties, especially if the developer must abandon (that is, remove from official maps) old streets or alleys. In Dallas, Peiser Corporation was investigating a site when it unexpectedly found that all abutting property owners had to agree to the abandonment of a mapped but never built alley. With 50 homeowners involved, the likelihood of unanimous agreement was almost zero. The developer passed on the site, despite having invested considerable time and money.

In addition to platting requirements, the subdivision may be subject to restrictive covenants imposed by the seller or a previous owner. Restrictive covenants should show up in the initial title search and, even if their en-forceability is questionable, they may have a profound influence on the type of development allowable.

Developers should be aware of opportunities and pitfalls caused by multiple, overlapping regulatory jurisdictions. Massachusetts, for example, is a “home rule” state, meaning that local authorities overlay many state approvals with their own, and vice versa. In home rule states, major land use changes can happen quickly, certainly within the timeline of even a modestly scaled development. In “Dillon’s Rule” states, such as Virginia, major regulatory change must often be authorized by state legislators, which usually means a developer will have a one- or two-year warning before such changes are enacted. A land use attorney can advise the developer on such issues. Although the public dissemination of land use information is improving with the advent of geographic information system (GIS) technology, many critical requirements are not available online—or if they are, their amendments are not. Some relevant codes are not even published in the commonwealth’s general laws. Developers should invest early in local expertise to

• identify all necessary approvals;

• provide realistic timelines in light of local customs; and

• advise on the likely content (and expense) of conditions or necessary mitigation.

The U.S. Supreme Court and Development Regulations

Although most subdivision regulation follows local and regional bodies, the U.S. Supreme Court plays an important role in the regulation of real estate development by ensuring that state and local regulations do not infringe on constitutionally protected private property rights. Each year, federal and Supreme Court rulings are written that clarify, and sometimes upend completely, commonly encountered land use regulations. Developers must rely on attorneys to keep abreast of changing regulation, but a few key decisions are important to understand. Most land deals cannot economically tolerate a lengthy litigation, so many developers accept regulatory intervention without question. Developers should not assume that regulators are knowledgeable about their legal authority.

• In Nollan v. California Coastal Commission (1987), the Court established standards for mitigation that require a “rational nexus,” between the impact and the required mitigation or regulated improvement.

• In Lucas v. South Carolina Coastal Council (1992), the Court held that if a regulation denies the landowner “all economically beneficial” use of his land, then compensation is required under the takings clause of the Fifth Amendment. The only exception to this rule is when the regulation affects an activity that was already barred under state law principles of property or nuisance law.

• In Dolan v. City of Tigard (1994), the Court established standards for regulations that require a landowner to dedicate land for public use as a condition of development approval. The government must be able to show a “rough proportionality” between the impact of the development and the public benefit that is being exacted. To date, the Court has not applied the proportionality rule to impact fees or other monetary exactions.

The Supreme Court also reviews federal regulations that affect development in areas including endangered species and wetlands.

• In Solid Waste Agency of Northern Cook County v. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (2001), the Court found that the corps lacked the authority under the Clean Water Act to regulate a wetland that does not physically abut a navigable waterway. The precise effect of this recent decision, which may affect vernal pools and other isolated wetlands, will likely depend on lower court rulings that address various fact-specific situations.

More recently, the Court has addressed the issue of takings for the purpose of economic development.

• In Kelo v. City of New London (2005), the majority opinion clarified the range of “public benefits” for which a taking of land was constitutionally justified. Further clarification based on individual facts is to be expected, and the proliferation of new kinds of land use regulation, such as urban growth boundaries, performance-based rules for stormwater, energy efficiency, and carbon, will likely be sources of continuing confusion over the next decade, as the courts catch up to industry and regulation.

Filing a Subdivision Application. Every jurisdiction has its own procedure for obtaining subdivision approval. Most jurisdictions have at least a two-stage process that requires approval from the planning commission and then the city council or county supervisor. California, for example, has a two-tier process. The first tier is the general plan, which defines land use for all parts of the city and is reviewed every five years. Most important for new subdivisions, it defines which areas are encouraged for development and which are not. General plans may also be linked to the capital budget for a city or county. The capital budget designates planned public expenditures for utilities, roads, parks, and other infrastructure improvements. The significance of the general plan is that it is relatively easy to obtain permission for zoning changes that are in accord with the general plan. Changes contrary to it—such as development in an agricultural zone or apartments in an area designated for single-family residences—may be almost impossible to get approved. Land that is designated for agricultural use must be changed to urban use, specifying property type and density, in the general plan before a specific plan (the second tier) can be created to develop the property. This step takes considerable lead time when general plans are revised only every five years.

Specific plans spell out the actual zoning, density, and, in some cases, the footprint, street access, and other details of the proposed development. Specific plans are even more detailed than zoning and, once achieved, may tie the developer to a particular development scheme. Changing a specific plan often requires a new round of public hearings and subjects the developer to the full risks associated with regulatory change. These risks have grown substantially in recent decades as more and more communities have attempted to curtail growth. Any public review can be highly politicized, giving the planning commission and city council the opportunity to impose new restrictions, to require more investment by the developer (exactions), or to lower the allowable density of development.

Phasing. Most subdivisions larger than about 200 lots are divided into phases. Even a much smaller development may be phased if the developer’s company is small and has limited resources, or if a portion of the land remains unavailable until later. Each phase typically involves a single filing of the plat and subdivision restrictions. Developers finance and construct utilities, roads, and other improvements necessary to create finished lots for each entire phase. Therefore, phases should not be so large that they cannot be financed or absorbed by the market in a reasonable time frame—usually within 18 to 24 months, or one economic cycle. Delineation of phases is a balancing act, because developers usually want the critical mass of a substantially complete development project as quickly as possible, to reassure buyers skittish about new communities. At the same time, communities may demand to review every aspect of a multiphase project at once, to assess impacts of the whole. Jo Anne Stubblefield, of Hyatt and Stubblefield, advises not to file more than the first phase of a project at the outset, especially for larger properties. Once plans are recorded, the developer may be held to them for a phase that is years away, limiting the ability to change with market conditions. Moreover, most of the regulatory process makes it advantageous to plat in smaller portions, again to preserve flexibility later if the market changes.15

REGULATORY CONCERNS. Land development regulation has become so complicated that it would take an entire book to describe the many different forms of regulation that a developer will encounter. Staying on top of new local ordinances is not enough. A developer must know which regulations are about to come into force, which are still under discussion, and which are only vague proposals. The lead times required to get a development off the ground are often long—and increasing. The more agencies involved, the longer it takes. Projects in California’s coastal zone and in environmentally sensitive mountain areas have been known to take ten years or longer to secure approvals. Litigation over public approvals for larger tracts is becoming the rule rather than the exception.

“Political involvement,” says Scott Smith of La Plata Investments, “is no longer just a good idea; it’s critical. Good relationship building with the city planner, city manager, and water/sewer officials is obviously necessary, but don’t forget larger issues. We work hard at developing relationships with state and national political parties—a move that may have seemed unjustified until now—when we face a ballot initiative that could kill development even of existing projects.”16

“What has changed … is really the intensity of competition for land entitlement. As competition for land entitlement (and associated costs) heats up, political involvement is becoming more critical,” according to Al Neely, formerly of Charles E. Smith Co. “If you are not a consensus builder, you just won’t make it. That means consensus at all levels, not just three or four government agencies, but community activists and advocacy groups as well. You have to engage people and get them on board.”17

Tim Edmond, former president of St. Joe/Arvida, adds, “Make sure you understand fully the cost and time required for entitlements, and then add 30 percent to your estimate.”18

Roger Galatas, president and CEO of Roger Galatas Interests in the Woodlands, Texas, advises that credibility with regulatory agencies is built with words and actions. “That means, do what you say you’ll do. Successful developers engage regulators themselves or send their most senior people. What does it say about you if you send someone junior to make your presentation to the planning board?”19 Four major regulatory issues affect most land developers today: vesting of development rights, growth controls, environmental issues, and traffic congestion.

Vesting of Development Rights. Historically, if developers could obtain zoning, they had the right to build what the zoning allowed. If they owned or bought a property that was already zoned, they were entitled, without public hearings, to develop the property within the limits established by the zoning. But this situation is no longer true in many parts of the country. If a court decides that the developer’s right to develop was not vested, despite having spent considerable money on improving the land, he may be denied the right to proceed. Standards for vesting vary widely. In development-friendly areas of the Southeast, vesting may be assumed at the preliminary plat (analogous to a general plan) and is secure at the final plat, subject to administrative renewals. In California, vertical construction may be required to prove vested development rights.

In California, Florida, and Hawaii, development agreements have become a popular solution to the problem of securing vested development rights. Development agreements, which are negotiated between the developer and the municipality, ensure that the ground rules under which a developer builds are the same as those that were in effect at the time the agreement was signed. Development agreements protect the developer’s right to build a specified number of residential units (or square feet of nonresidential space) in exchange for providing certain facilities to the community. The validity of development agreements are currently being tested in court, and the outcome will determine whether the obvious advantages of these contracts for both sides can be reliable.

Growth Controls. Growth management programs focus on guiding community development and responding to development proposals comprehensively, rather than piecemeal as applications are submitted. They are used to ensure a level of quality in development, including conservation of open space, and that infrastructure is in place to support new development as it occurs.

Growth management provisions are often incorporated in local zoning ordinances. They typically include

• linkage of zoning approvals to capital budgeting investments in infrastructure;

• establishment of growth boundaries to limit the supply of developable land and direct density to urban centers and transit nodes;

• ceilings on the number of housing units or square feet of space that can be constructed in the jurisdiction, or annual quotas on building permits;

• linkage of development and availability of water supply, sewage capacity, or, conceivably, any limited natural resource; and

• linkage of projects and specific public facilities, such as schools, transit, or road improvements.