Among the key planning concepts with which a developer should be familiar are conservation development, cluster development, new urbanism, and PUDs.

“Conservation development” is an approach to exurban community development that proposes that sensitive landscapes and development can coexist. Conservation communities can range in size from a few acres to thousands, but they generally have several items in common. They usually include legal protections for some areas of the plan, such as a conservation easement. They also typically control housing design to a greater degree than comparably located subdivisions.

Clustering is the most common zoning-approved method of conservation development. In cluster development, higher densities in certain areas permit protected open space elsewhere on the site. Following traditional zoning, overall, gross density usually remains the same for cluster developments as for traditional tract housing where housing is spread more uniformly over the entire tract. Each cluster may contain homes of a similar style, and styles may vary among clusters, imparting an individual village character to each. Cluster planning requires more design skill than conventional subdivision planning; unskilled planning or exploitation of the cluster concept can easily generate an unattractive bunching of dwellings.

“New urbanism” offers another alternative to conventional subdivision design, emphasizing traditional neighborhood planning based on grid street patterns. Featuring narrower streets with sidewalks, small public squares and parks, narrower lots with rear garages to manage car traffic, and walkable town centers, this approach proposes land use patterns similar to those of traditional cities and towns. Seaside in Walton County, Florida, is among the earliest examples of the new urbanist approach, and its success has spawned hundreds of development plans that refine the core concepts. New urbanism typically relies on typological coding, rather than zoning, as its primary regulatory tool. Coding, which is more design-oriented than zoning, specifies building, street, and open space “types” for each lot in the development without dictating uses. The results are a mixed-use, mixed-housing-type community, flexible enough to accommodate many uses, but conforming more or less to a formal design for the streetscape.

Beginning developers aspiring to these characteristics should be advised: it is not as simple as it sounds. First, the more comprehensive design vision of a community like Seaside requires substantially more attention and expense in the design phase, which can be tough for a small firm to sustain. Second, the consistent vision of a master-planned community requires legal structure, governance documents and boards, and operational funding for common area maintenance, as well as ongoing design review and builder oversight. This “software” is just as complex as the actual construction. Third, many developers have encountered trouble when shaping community plans to a formal ideal without adequate research to prove a deep market for the resulting mix of home typologies. That said, demographics clearly support more of this type of development, particularly the aging of the U.S. population and the increasing diversity of household types that are poorly served by conventional suburban houses. The Congress for New Urbanism and other professional advocacy groups offer an array of symposiums and training opportunities for individuals to learn about these ideas.

Whereas conservation and new urbanist development are design and governance concepts, PUD is a legal concept. PUDs are zoning classifications typical in many jurisdictions, under several common names, such as planned residential development or planned residential unit, but the purpose remains the same. In PUDs, traditional zoning classifications are discarded in favor of a more flexible approach that considers the project in its entirety instead of in zoning overlays. The PUD is approved as an entity and is essentially a customized rezoning for a desirable project. It may combine commercial and residential uses, include several types of residential products, and provide open space and common areas with recreational and community facilities.

In a PUD, residential areas may be outlined and a certain number of units designated, but no detail regarding the specific site plan is required for approval. Most jurisdictions require later public review of the specific site plan; some treat this review as cursory, if the plan is being followed. Developers have the right to build a certain number of units or a certain number of square feet of commercial or office space as long as they conform to the stipulations of the PUD ordinance.

PUDs usually involve negotiations between the developer, the reviewing agencies, and the public. The negotiations give the community an opportunity to tailor development proposals to meet community objectives. Often, the developer will be required to place more land in open space or to commit more land or cash to community facilities than originally planned. In return, the developer may receive permission to build more units than the regular zoning would allow.

Planning and development trends have been leaning toward greater mixing of land uses. Planners, developers, and the public have discovered that a considered mix of uses can create a more functional and pleasing environment, with benefits to local ecology, infrastructural efficiency, and public health.

After the site investigation has been completed and base maps prepared, the land planner should present the developer with a site plan that describes a number of different approaches toward developing the site. The site plan, which combines information regarding the target market with the base map, must consider many different items:

• topography;

• geology and drainage;

• natural vegetation;

• vistas and sight lines;

• private and public open spaces;

• neighboring uses;

• easements and restrictions;

• roads;

• utilities;

• patterns of pedestrian and bicycle and other vehicular circulation—ingress and egress, sidewalks, and alleys;

• market information;

• sales office location, visitor parking, and other temporary operational concerns;

• buffers for noise and privacy; and

• building types.

The design process involves considerable trial and error, and it can quickly spiral out of control without a dedicated project manager. Developers must consider future users and their relationship to every aspect of the site. The site planner first produces a diagram showing constraints and opportunities with all the site’s relevant features—undevelopable slopes and wetlands, neighboring uses, view corridors, arterial roads, access points, streams, forests, and special vegetation. Next, using the developer’s land use budget from the market analysis, the site planner prepares alternative layouts showing roads, lots, circulation patterns, open space, amenities, and recreation areas.

Throughout the schematic planning phase, developers must ensure that the plan will meet their marketing and financial objectives. They should mentally drive down every street, examining traffic patterns, and consider such aspects as attractive vistas, landscaping, and homeowners’ privacy. They should also envision the entrance to the subdivision, playgrounds, and street crossings. Sequence and the sense of arrival are key elements that the developer should always keep in mind.

A team approach usually works best, and the contractor, civil engineer, political consultant (if needed), and especially sales and marketing staff should be involved as early as possible. Rough drawings of alternative schemes should be reviewed at regular intervals. Another way to develop a plan is by holding a charrette in which the land planners work with the public, community leaders, and other representatives to incorporate their concerns and ideas. This model of public participation, if handled correctly, allows stakeholders to feel they had a say in shaping the proposal. If handled poorly, it is a recipe for disappointment and expense. Charettes are work sessions with the public, but decisions should never be announced in this environment. The project design team is ultimately responsible for fulfilling the development’s objectives, and the desires of any other stakeholder must be considered but only adopted if they add value to the proposal.

When the developer is satisfied with the schematic plan, the planner produces the final version. The final plan also goes through several iterations. Because it will ultimately be submitted to the city for plat approval, the final plan must show the boundary lines, dimensions, and curvatures of every lot and street. Jurisdictions typically offer detailed guidelines for these submittals, but it has become common for these guidelines to include a troubling line: “… and anything else that may be requested for departmental review.” Developers must meet with reviewers early on and obtain a clear list of what documentation, including engineering calculations, will be required for review and approvals.

Design guidelines provide an important tool for land developers in setting the tone and overall appearance for a subdivision. In master-planned communities, detailed urban design guidelines can cover all aspects of design, from the streetscape and landscaping to individual house sites, materials, setbacks, and architecture. Although guidelines that are too severe can create monotonous subdivisions where everything looks alike, well-crafted guidelines can help establish an attractive subdivision. Creating design guidelines is a skill that may not be within the capability of the project planner. There are firms specializing in coding and guidelines, but developers should coordinate such documents closely with the attorney drafting the governance documents for property owners’ associations, understanding that the association, or its agent, will need the legal authority, design support, and operational budget to follow through for many years. Developers should also be sure to retain the right to modify guidelines if buyers react negatively to the initial approach. Architectural guidance should be framed positively: “How porches can create an active streetscape” rather than “all porches must be eight feet deep and painted white.”

The design process begins with a base map that delineates the parcel’s relevant physical and legal features. All subsequent design schemes are drawn on the base map. Zoning and other resource mapping and aerial photos are often available for download from planning departments or from private companies. Aerial photos are invaluable for understanding the property, as well as for marketing the project later. City halls, local libraries, utility agencies, state highway departments, and local engineering firms are sources for topographic maps, soil surveys, soil borings, percolation tests, and previous environmental assessments. Title companies and the development attorney are the sources for existing easements, rights-of-way, and subdivision restriction information.

TOPOGRAPHIC SURVEY. Site planning begins with the topographic map that shows the contours of the property, rock outcroppings, springs, marshes, wetlands, soil types, and vegetation. Although topographic maps are available for many counties, a custom-drawn topographic survey is invaluable for sites with significant grading. In tight subdivisions, or on sites with substantial vegetation, on-site surveys are often needed to obtain more accurate information in specific areas. The topographic map should show

• contours with intervals of one foot (0.3 m) where slopes average 3 percent or less, two feet (0.6 m) where slopes are between 3 and 10 percent, and five feet (1.5 m) where slopes exceed 10 percent, with the caveat that the reviewing engineer or zoning may require a specific interval for final approval;

• existing building corners, walls, fence lines, culverts and swales, bridges, and roadways;

• location and spot elevation of rock outcroppings, high points, watercourses, depressions, ponds, marsh areas, and previous flood elevations;

• location and spot elevations of any on-site utility fixtures or emergency equipment;

• floodplain boundaries (determine in advance which boundary the jurisdiction will require);

• outline of wooded areas, including location, size, variety, and caliper of all specimen trees;

• boundary lines of the property; and

• location of test pits or borings, such as for bridge locations, to determine subsoil conditions.

SITE MAP. Developers should prepare a vicinity map at a small scale that shows the surrounding neighborhood and the major roads leading to the site. The map can be later adapted for marketing, loan applications, and government approvals. In addition to location information, the map should show

• major land uses around the project;

• transportation routes and transit stops;

• comprehensive plan designations;

• existing easements;

• existing zoning of surrounding areas;

• location of airport noise zones;

• jurisdictional boundaries for cities and special districts, such as schools, police, fire, and sanitation; and

• lot sizes and dimensions of surrounding property.

BOUNDARY SURVEY. The boundary survey shows bearings, distances, curves, and angles for all outside boundaries. In addition to boundary measurements, it should show the location of all streets and utilities and any encroachments, easements, and official county benchmarks from which boundary surveys are measured or triangulation locations near the property. It is important to know which elements the lender will require—typically the American Land Title Association standard—and also to think ahead to requirements of the final plat and engineering review.

The boundary survey should include a precise calculation of the total area of the site as well as flood areas, easements, and subparcels. Calculations of area are used to

• determine the number of allowable units based on zoning information;

• determine net developable area (the size of this area serves as the basis for both site planning and economic analysis of the project);

• determine sale prices—often, sale price is calculated per square foot or per square meter (for instance, $2 per net developable or gross square foot [$21.50/m2]) rather than as a fixed total price; and

• provide a legal description of the site.

UTILITIES MAP. The utilities map is prepared at the same scale as the boundary survey. It shows the location of

• all utility easements and rights-of-way;

• existing underground and overhead utility lines for telephone, electricity, and street lighting, including pole locations;

• existing sanitary sewers, storm drains, manholes, open drainage channels, and catch basins, and the size of each;

• rail lines and rail rights-of-way;

• existing water, gas, electric, and steam mains, underground conduits, and the size of each; and

• police and fire alarm call boxes.

CONCEPT DEVELOPMENT. Once base maps have been prepared and gross and net developable acreage calculated, the true design process begins. Before the planner begins drawing, the developer should define the target market, the end product (including lot sizes), and the approximate number of units needed to make the project economically feasible.

The 7,000-acre (2,800 ha) Lake Nona property in Orlando, Florida, includes 2,000 acres (800 ha) of lakes and open space. Development includes office and retail space, medical and educational facilities, and nearly 2,000 residences.

LAKE NONA PROPERTY HOLDINGS, LLC

Base maps outline developable areas as well as features such as lakes, stands of mature trees, and hills on the site. The developer determines which features should become focal points for the design based on the site’s physical condition and specific market. For example, although a creek and its floodplain are often excluded from the developable area because of potential flooding problems, it may be the site’s best feature when used as a focal point for public open space or as a private amenity for certain lots. Most likely, it also performs a vital drainage function that may be expensive and destructive to alter.

The goal of site planning is to maximize the value of the property subject to market absorption and zoning constraints. Lots with views, or that adjoin open space or water, sell at a premium. Developers may achieve high returns by placing higher-density products such as townhouses, multifamily housing, or zero-lot-line homes next to valued features. Lots that do not front on these features will sell for more if the plan provides them physical and legal access. The best plans create value by using a desirable feature as a generator of lot premiums—for example, a town square with houses fronting it. The public has access to the square and its surrounding streets, while the houses that front on it have special views. A lake, golf course, or other active or passive recreational amenity could similarly enhance value.

If the development’s use is perceived as incompatible with adjacent uses, the project may be contested by local residents. For example, if single-family houses face a developer’s property, any non-single-family use is likely to draw objections from the neighbors. Although different uses on adjoining properties are appropriate in many situations, the burden falls on the developer to demonstrate the reason for not maintaining consistency in use or density.

Many residential tracts border major streets. Because such commercially suitable frontage usually sells for three to five times the value of single-family land, the developer may wish to consider placing retail, office, or multifamily uses with ground-floor commercial space at these locations. The risk of reserving a large amount of commercial or multifamily frontage at the edge of the development is that, in the event of a slow market, the vacant lot serves as an unattractive front entrance to the project. If frontage is retained for future development, the entrance into the residential portion of the tract should be carefully designed and landscaped. A parkway entrance with an entrance feature and landscaping has become a common element of many subdivisions, but more urban-style options that play down the entrance and connect seamlessly to adjacent developments are gaining favor. The key is to communicate arrival, and quality, in other ways, such as with a consistent design aesthetic, material palette, street furniture, lighting, and signage.

In the design of street systems for a new development, a street’s contribution to the neighborhood environment is as important as its role as a transportation link. The street system should be legible to visitors so that the intended function of a particular street segment is readily apparent.

Although debate over the appropriate functions and definitions of street types persists, the concept of a hierarchy of streets remains practical. The commonly used functional classification of streets includes, in ascending order, local streets, collectors (sometimes called “boulevards” or “avenues”), and arterials (including freeways).

• Arterial Streets—Arterial streets are seldom created as parts of new subdivisions. The primary purpose of arterial streets is mobility—movement of as much traffic as possible as fast as is reasonable—and the mobility function of arterials therefore overshadows their function of providing access to fronting properties, such as residences or commercial uses.

• Collector Streets—Collector streets serve as the link between arterial streets and local streets. Typically, they make up about 5 to 10 percent of total street mileage in new developments. Increasingly, new collector streets are fronted by active properties, such as neighborhood commercial centers, institutions, and multifamily residences.

• Local Streets—Local streets usually account for around 90 percent of the street mileage in new communities and are intended to provide access to the residential properties fronting them. As the preponderant class of streets in terms of mileage, they contribute much to the signature of their neighborhoods. They also constitute the backbone of neighborhood pedestrian and bicycle networks.

When designing streets for a new development, designers should begin with the minimum width that will reasonably satisfy traffic needs. On most local streets, a 24- to 26-foot-wide (7.3–7.9 m) pavement is appropriate. This width provides two parking lanes and a traffic lane or one parking lane and two moving lanes. For lower-volume streets with limited parking, a 22- to 24-foot-wide (6.7–7.3 m) pavement is adequate. For low-volume streets where no parking is expected, an 18-foot-wide (5.5 m) pavement is adequate. It has been found that widening access streets a few more feet does not increase capacity, but it does encourage higher driving speed. A wide access street also lacks the intimate scale that makes an attractive setting. Designers should consider the viability of bicycle traffic to evaluate whether any widening might be better used for bike lanes, which can expand the nonmotorized domain on the street.

A residential collector street should be designed for higher speed than local or access streets, permitting unrestricted automobile movements. Residential collector streets 36 feet (11 m) wide provide for traffic movement and two curb parking lanes. When parking is not needed, two moving lanes of traffic are adequate, with shoulders graded for emergency parking.35 Designers should keep in mind that a street section, once chosen, need not remain constant for the length of the street. In fact, special moments in street design, such as expanding sidewalk area periodically to allow outdoor dining or allowing nose-in diagonal parking to alternate with traffic-calming landscape elements, are powerful signals that something of value is happening in these locations.

Residential streets should provide safe, efficient circulation for vehicles and pedestrians and should create positive aesthetic qualities. The character of a residential street is influenced to a great extent by its paving width, its horizontal and vertical alignments, and the landscape treatment of its edges. Residential streets are community spaces that should project a suitable image and scale. For example, much of the character of older neighborhoods is derived from the mature street trees that form a canopy over entire streets, whereas a neighborhood with wide streets devoid of trees conveys an entirely different image. Vertical elements, including not only trees but light posts, shading structures, bollards, and signs, can be more important than the surface of the street in communicating pedestrian safety and insulating lower-floor building programs from the effects of traffic.36

Straight streets with rectangular lots give a more urban ambience, whereas curvilinear streets tend to create irregularly shaped lots and provide a more pastoral feel. A minor problem for the developer is that irregular lots may have to be resurveyed when the builder is ready to start construction because the iron pins that mark lot corners tend to get moved or lost during construction of other houses.

Adequate grading and the optimal provision of utility services are important elements of site design, and the cost of providing them is critical to a project’s bottom line. Developers should never leave the decision about these elements to the civil engineers; the lowest-cost site engineering is rarely the most profitable subdivision design. The developer’s objective is to maximize the sale value of the lots subject to efficient site engineering, but this value may also derive from a harmonious relation between built and natural landforms.

GRADING. The grading plan must contain precise details and take into consideration such factors as the amount of dirt that will be excavated, the finished heights of lots, steep areas that may require retaining walls, and graded areas that may be subject to future erosion (developers are liable for erosion even after they have sold all the lots on a site). Grading is used as an engineering tool to correct unfavorable subsoil conditions and to create

• drainage swales;

• berms and noise barriers;

• roads and driveways, plazas, and recreational spaces;

• topsoil at a proper depth for planting;

• circulation routes for roads and paths; and

• suitable subsoil conditions and ingress for facilities.

Grading is also used for aesthetic purposes to provide privacy, create sight lines, emphasize site topography or provide interest to a flat site, and connect structures to the streetscape and planting areas.

Homebuilders usually do their own fine grading of lots in addition to that done by the land developer, but they expect—and may be contractually entitled to—a buildable site with no grading required other than topsoil clearing. When the final foundation location is unknown at the time of sale, developers should be extremely careful about such promises. When homebuilders feel a site requires fill, the developer may receive a request for a rebate of fill and trucking costs, if expectations are not set appropriately at the time of sale or option.

STORM DRAINAGE AND FLOODPLAINS. Storm drainage systems carry away stormwater runoff. In low-density developments with one-acre (0.4 ha) lots or larger, natural drainage may suffice, and generally natural approaches are more cost-effective. In denser developments, however, some form of storm drainage system is always needed, and the best design may be a hybrid of conventional and low-impact techniques.

Gently rolling sites are the easiest and cheapest to drain; flat sites and steep sites are more difficult and expensive. As with other environmental issues, drainage problems can come back to haunt a developer long after the lots have been sold, and these issues can be difficult to predict.

If a property contains any hint of wetlands, a floodplain study is among the first studies a developer should commission before buying a site. Developers should understand where the property lies in relation to floodplains. They can start by obtaining the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s flood hazard boundary maps (see www.fema.gov), or flood hazard GIS data from the municipality. Land that is within the 100-year floodplain—that is, the area that is expected to flood once every 100 years—is usually not developable except for uses such as golf courses, parks, or storage of nontoxic materials. Even if uses are permissible, developers should consider whether they make sense, and whether the resulting structures will be insurable.

In some localities, land within the 100-year floodplain is developable, albeit with restrictions, and structures can be mortgaged by federally insured institutions only if the structure carries flood insurance. To alter floodplain areas, developers must apply for a permit from the EPA, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, or other body, such as state environmental or natural resources agencies, with authority over the local wetlands or creek system. The Army Corps of Engineers designates floodways as well as 100-year floodplains. A floodway is that portion of a channel and floodplain of a stream designated to provide passage of the 100-year flood, as defined by the corps, without increasing elevation of the flood by more than one foot (0.3 m). Developers may not build within floodways. Floodways must retain the same or better rate of water flow after development as before it; otherwise, floodplain elevation is likely to rise upstream from the development, causing increased flooding in those areas. Developers can alter the floodway, but any changes must be engineered properly to preserve water flow and must be permitted by the appropriate authorities, including the Corps of Engineers.

Sterling Collwood is a 260-unit student rental community in San Diego, California. More than half the site is set aside as green space, restored with native plants.

HUMPHREYS & PARTNERS ARCHITECTS, L.P.

DON RUSSELL, PRODIGITAL REAL ESTATE PHOTOGRAPHY

Irrespective of the frequency with which they flood, areas within a property may be defined as wetlands and thus come under the jurisdiction of the EPA as well as other federal, state, and local agencies, such as the corps and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, or more commonly, the state department of environmental quality. Often, all agencies must be satisfied before the Corps of Engineers will issue a permit to disturb a wetland.

Wetlands come in many forms, including ephemerally wet swales, intermittent streams, hardpan vernal pools, and volcanic mud flow vernal pools. Regulatory streamlining has encouraged coordinating agencies to adopt standard definitions of these features, but delineation is, ultimately, done by an individual field biologist or hydrologist on site, and jurisdictional determination is subjective.

In evaluating a site that contains potential wetlands, developers should hire a qualified biologist to conduct a preliminary wetlands evaluation report, to map potential wetland sites on the property, and to suggest mitigation measures and alternative approaches to the design of the property.37 Developers should be aware that some features, such as vernal pools, may be only seasonally visible, meaning that a project that is ready to go in September may be delayed by six months for a complete wetland delineation.

LOW-IMPACT DEVELOPMENT. Several aspects of land development can adversely affect site hydrology in multiple ways. Expansion of impervious surfaces and changes in vegetation can concentrate and accelerate surface stormwater flow. The introduction of vehicles, new uses, and landscape maintenance regimens can increase pollutant discharge, and the combination of increased water use and reduced permeability can impair the recharge of aquifers on which the development and surrounding uses depend. Low-impact development (LID) water quality management strategies can make up an integrated approach to improve water quality.

Integrated LID methods can result in better environmental performance while reducing development costs when compared with traditional conventional stormwater management approaches.38 LID techniques are a simple yet effective approach to stormwater management that integrates green space, native landscaping, natural hydrologic functions, and other techniques to generate less runoff from developed land. These processes can also remove pollutants, such as nutrients, pathogens, and metals from stormwater.39 In short, LID is used to maintain—as closely as possible—the benefits of natural site hydrology and to mitigate the adverse effects of stormwater runoff and nonpoint source pollution associated with some conventional stormwater management methods.

Common LID practices include the following:

• Conservation Design and Impervious Surface Reduction—Following conservation design methods, such as clustered housing, shared driveways, and narrower roadways, as well as rainwater collection systems on buildings, can reduce the overall impervious surface and decrease stormwater management costs.

• Bioretention (Rain Gardens)—A bioretention cell is an engineered natural treatment system consisting of a recessed landscaped area constructed with a specialized soil mixture and site-appropriate vegetation. Slightly recessed, the cell intercepts runoff, allowing the soil and plants to filter and store runoff; remove petroleum pollutants, nutrients, and sediments; and promote groundwater recharge through infiltration. These “rain gardens” can be relatively inexpensive to build and can become site amenities.

• Temporary Erosion Control—More ecologically sensitive approaches are not limited to permanent installations. Up to a quarter of stormwater management costs can be expended on temporary measures of erosion control during construction and landscape establishment. Filter-fabric and compost constructions have increasingly been deployed in lieu of silt fences and check dams in these applications. Typically costing more to install, these measures can be deployed so that they remain in place permanently, making the life-cycle cost comparable with conventional measures.

• Vegetated Swales, Buffers, and Strips—Constructed downstream of a runoff source, a vegetated or grassed swale is an area that slows and filters the first flush of runoff from an impervious surface. From both a budget and an environmental perspective, swales are nearly always preferable to culverts.

• Permeable Pavement—This type of pavement allows stormwater to infiltrate the soil. Materials and maintenance costs are substantially more expensive than conventional pavements, but their use can radically reduce impervious surface, a metric that is increasingly evaluated by approval authorities.

• Low-Impact Landscaping—Increasingly, native plants may be specified for site landscaping. These varieties are often more expensive, but they reduce operational cost and impact and require less water and maintenance.

• Green Roofs and Rainwater Collection—Capturing rainwater for reuse and slow discharge reduces concentrated runoff. Green roofs capture rainwater while improving buildings’ thermal performance in several ways. As designers and contractors become more skilled, the typically large cost differential is falling rapidly, and historical concerns about maintenance have been addressed. Still, these are complex systems, and experienced designers and installers are the key to successful implementation.

Demonstrated by multiple EPA case studies, the use of LID practices can be both fiscally and environmentally beneficial to developers and communities. These systems can often substitute for more expensive elements like curbs and gutters, and sometimes they can reduce requirements for intensive site engineering, such as flood-control structures.40 In case studies, capital cost savings have ranged from 15 to 80 percent when LID techniques were used.41 Engineering departments increasingly recognize low-impact best management practices as functionally superior, or at least equivalent, to conventional stormwater measures. It is likely that virtually all developers will soon use a mix of conventional and LID techniques, and communities in very sensitive areas, or projects seeking sustainability certification, will benefit from a comprehensive LID system. The best examples of LID use functional features as landscape amenities, in ways that increase value, and studies have shown that attractive implementations of these systems can result in developments that appreciate at a higher rate than conventionally designed subdivisions.42 Whether they are used comprehensively or à la carte, familiarity with these systems is now an absolute necessity for planners, landscape architects, and site contractors, and only an experienced team can advise a developer on the suitability of these types of techniques for a particular site.

SANITARY SEWERS. The layout of the sanitary system is determined by the topography of the site and the location of the outfall point—that is, the point of connection to the sewer main. Sewers are primarily gravity driven, so if the sewer main that connects the subdivision to the treatment plant is not located at the low point of the site, the developer may have to provide a pumping station, which brings both construction and operational expense.

Beginning developers should avoid tracts of land for which nearby sewage and water services are not available because the cost of bringing these services in from off-site locations can be prohibitive. When major off-site utility improvements are necessary, developers usually require a minimum of 200 homes to recoup their investment and risk. Creating a utility district to provide service or building a plant where none exists typically takes two or more years, as well as significant front-end investment, and can entail substantial operational and legal entanglements.

One option available to developers whose sites do not have sanitary service is to buy or lease a package treatment plant, a small self-contained sewage treatment facility, to serve the subdivision and to design the system to tie eventually into the community’s system. This option can work in rural areas and in communities that are accustomed to working with package treatment technology.

Septic tank systems are usually feasible only in rural areas. Their use depends on soil conditions and, in most areas, they are allowed only on lots of at least one-half acre (0.2 ha). A minimum of one acre (0.4 ha) is typical. If a well is included on the same site as a septic tank, even larger lots are sometimes necessary to prevent contamination of the well water, and health department approvals will be contingent on an adequate physical separation of the two, usually both by distance and by extending the well casing’s grouted seal.

In planning a sewer system, the developer should investigate

• sewage capacity requirements, which may vary, but 100 gallons per day (379 L/day) per person is common;

• available capacity of the treatment plant and connector lines;

• number of hookups contracted but not yet installed;

• the municipality’s method of charging for sewer installation; and

• the people responsible for issuing permits and establishing requirements for discharging treated sewage into natural watercourses.

Sanitary sewer lines are normally located within street rights-of-way but not under road pavement. House connections to sewers should be at least six inches (15 cm) in diameter to avoid clogging; all lateral sewers should be at least eight inches (20 cm) in diameter. Sanitary lines and waterlines should be laid in different trenches where possible, although some cities allow a double-shelf trench that contains the sanitary sewer on the bottom and the waterline on the top shelf. Except in very high-density communities, these “wet” infrastructure elements should not be colocated with power and voice and data communications services.

WATER SYSTEM. A central water system is standard in urban communities. Like the requirements for sewage capacity, those for water supply vary, but 100 gallons per day (379 L/day) per person is common. Requirements can vary greatly in their calculation of occupant load: jurisdictions may count bedrooms, bathrooms, or habitable square footage.

Water mains should be located in street rights-of-way or in utility easements. Residential mains average six to eight inches (15–20 cm) in diameter, depending on the water pressure. Branch lines to houses are three-quarter-inch or one-inch (2 or 2.5 cm) pipe connected to a five-eighths- or three-quarter-inch (1.5 or 2 cm) water meter, respectively. Because waterlines are under pressure, their location is of less concern than that for sewer lines, which rely on gravity flow.

Developers should consult the fire department about requirements for water pressure and the placement of fire hydrants. The fire department is likely to restrict the depth and slopes of culs-de-sac and the maximum distance between fire hydrants and structures. Fire department requirements, like road requirements for emergency services, are increasingly used as “backdoor” development restrictions, and developers should be aware very early of these requirements.

Water, sewer, and drainage lines should be installed before streets are paved. If installation before paving is not possible, developers should install underground crossing sleeves where the lines will cross the streets so that the utility contractor can pull the lines through later; otherwise, streets will have to be torn up to install and maintain lines.

UTILITY SYSTEMS. Electricity, gas, telephone, and data cable services are typically installed and operated by private companies, although in the case of underground electrical service, it is not uncommon for the site contractor to act as the utility’s agent. Designating the location of utility easements is an essential step in the process of land planning. If the land planner does not specify a location, the utility company may do so with little regard for aesthetic considerations. Usually, easements run with the street right-of-way, and along the back or side lot lines, within five or ten feet (1.5 or 3 m) of each lot. Most planners prefer to place all electrical power transformers underground or in semiexposed secure cabinets, but local custom and ordinances may dictate whether lines are above- or belowground. Local power companies often communicate their preference with prohibitively high costs for the less preferable option. The installation of transformers underground can be done at a reasonable cost and can prevent vandalism and the need for frequent maintenance. Transformers located aboveground can be hidden and protected from vandals by wooden lattices or painted metal cabinets with thorny shrubs or similar landscaping devices. Landscaping for these areas should closely follow the utility’s operational guidelines, as it is almost certain that major work will occur here as homes are built in the development.

FIGURE 3-9 | Typical Designs for Bioretention Basins

Although electricity, gas, telephone, and cable tend to play a smaller role in site design than do public utilities, such as water, sewer, and drainage, they still determine where structures can be built on each lot. Because the rapid development of data infrastructure has reshaped so many aspects of domestic and work life, many developers have made major investments in fiber-optic network installation for their communities. The value of these networks to retail lots or homebuyers over time is not known. Developers of communities must think beyond the year or two of the development period and consider not just the function of the utility service but the durability of the “deal” they have made for their customers, by committing to providers. Developers have, in some cases, saddled their communities’ residents with long-term contracts in order to get affordable and high-quality service, only to find that falling costs make their packages unattractive in just a few years. The safest approach is to attempt to “future-proof” development projects by installing additional empty conduit and equipment space during development, when unit costs are low. In this way, a disruptive technology can, as long as it fits in the pipe, be accommodated at modest cost later.

The developer should talk to each utility provider as early as possible. Utilities are by nature uncompetitive, and within their concession area, providers may have little incentive to move quickly or improve service. Delays in obtaining services are common and can easily throw off the developer’s schedule and hold up final sales.

Lot size and layout should reflect the nature of the surrounding community. It is especially important in an infill site to match the character of the new development with its surroundings. A developer should not try to suburbanize an urban community with deep setbacks, wide lots, and side garages. Alternatively, a compact development in a rural setting may not be appropriate or marketable.

Two determinants of a community’s layout are lot width and garage placement. Many postwar suburban subdivisions were designed with wide lots—some up to 100 feet (30.5 m) to accommodate a house and a two-car garage and driveway. More recently, 25- to 40-foot (7.6–12.2 m) widths have become more common. The new urbanist approach embraces the concept of narrower lots, smaller frontyards, and garages at the rear of lots, typically accessed by an alley. This layout creates a better streetscape because the view is not dominated by garage doors. For developers, this approach can be desirable because it allows the placement of more houses on the same length of street, saving per-unit infrastructure costs.

In the past, attached townhouses tended to be sited in rows surrounded by parking lots. Today’s townhouses often include individual garages that are tucked under the living space at the front or rear or in separate, dedicated buildings at the rear. Garage townhouses can be very cost-effective for builders and developers because they use less land and cost little more to construct.

Sidewalks, curbing, planting strips, and catchment basins must all be adjusted to the density and price point of the development. A single-family subdivision of 20,000-square-foot (1,860 m2) lots on minor streets need not be developed with the same street improvements required for a higher-density subdivision on 2,500- to 4,000-square-foot (230–370 m2) lots.

If the development adjoins a busy street, that edge must be handled with great care. Ideally, the community should not turn its back on the street but should take advantage of the traffic and activity and turn it into an asset. If the project is a mixed-use development, this location could be ideal for intensive uses, such as a retail district. Or it could be the site of neighborhood facilities, particularly if they are shared with the greater community, such as schools, libraries, or parks. If houses must be sited along a busy street, visual and sound buffering may be needed, which could take the form of service streets, landscaping, or site walls, or potentially upgrades to the building envelope. If sound isolation is required, developers are advised to retain acoustic consultants, as landscape effects on noise can be highly unpredictable.

Because lots facing busy streets may yield lower prices than interior lots, the developer should consider ways to boost their appeal or possibly use them for lower-priced units. Experienced developers, like good architects, understand which items can create value. But even experienced developers should spend time in the field investigating why people react more favorably to one design element than to another. The need for market research cannot be overemphasized. Successful developers always review the competition, use focus groups, and collect exit data from potential buyers who stop at sales offices or visit community websites or events.

Buyers react differently in different markets to both location and cost. For example, in western states, many buyers prefer single-level houses, whereas in the Northeast they are usually considered less desirable. In urban areas, buyers may like three-level townhouses, while farther from large cities, only a single-family house will do. Buyers may like certain features, such as deeper frontyards, but may not be able to afford the additional land cost. Good market research can reveal buyers’ preferences in the target market.

Throughout the country, land cost as a percentage of house value has risen steadily since the 1960s, from 15 to 25 percent on average. In certain areas of major cities, land costs may exceed 50 percent of the house’s value.

In response, traditional housing types are being rescaled and redesigned for modern use. Bungalows and cottages on small lots are particularly suited to move-down empty nesters, single parents, and others who make up today’s smaller households. Townhouses are a popular housing type in both urban and suburban areas, offering an alternative to those who do not want the maintenance of a single-family house. Townhouses are not always lower-priced options and can be as upscale as any other housing.

Large estate houses in exclusive communities remain an American icon that appeals to certain market segments. In many areas, estate-style houses are now being rescaled to fit on quarter-acre (0.1 ha) lots. These houses (called small-lot villas or, pejoratively, McMansions) typically have highly articulated two-story facades that face the street, giving an impression of height, volume, and high quality.

ZERO-LOT-LINE OR PATIO HOMES. Traditionally, local zoning codes have established minimum side yard setbacks ranging from three feet (0.9 m) to 10 percent of the lot width. Three- or five-foot (0.9 or 1.5 m) side yards result in unusable spaces. Windows from one house often look into windows of the next house, only six feet (1.8 m) away. To make side yards more usable, zero-lot-line lots, which allow densities up to nine units per acre (3.6/ha), were created. Today, most major cities and high-growth counties have modified their zoning codes to allow them.

A zero lot line means that the house is left or right justified; that is, one side of the house is built on the lot line so that the opposite side yard can occupy the total width available (10 feet [3 m] is considered the minimum width for usable space). The side of the house on the lot line is usually a windowless, but not shared, wall. Each lot must take care of its own drainage. If builders design a roof that drains water onto the next property, they must obtain a drainage easement from the owner of that property. In addition, a maintenance agreement, which can be made before construction while the builder or developer owns all the lots, must be recorded if using the neighbor’s lot is necessary to maintain the wall on the lot-line side of the house. Creative architects have mastered the challenge of designing zero-lot-line homes (also called patio homes) by making good use of the outdoor space and developing floor plans and elevations that maximize light and space (see figure 3-10 for various zero-lot-line configurations and associated densities). Small-lot, high-density housing must be carefully coordinated with scattered-lot or multiple-builder land sale programs. The land plan, in fact, should be drawn up concurrently with the house plan. The lot layout should seek to achieve a variety of goals:

• a site that does not require excessive grading or unusually deep foundation footings;

• the presence of sufficient usable area for outdoor activity (one or two larger areas are preferable to four small areas);

• adequate surface drainage away from the house, with slopes running toward the front or rear of the house; land developers should grade the lots so that they all drain toward the storm drainage system;

• minimum on-lot grading and maximum retention of specimen trees; and

• a minimum number of adjoining lots—preferably no more than three (one on each side and one along the back).

OTHER SMALL-LOT VARIATIONS. Variations of the zero-lot-line concept include Z-lots, wide-shallow lots, and zipper lots. Z-lots are shaped like a Z, with the house placed on the diagonal between its frontyard and backyard. The concept yields seven or eight units per acre (17 or 20/ha).

In wide-shallow developments, lots are 55 to 70 feet (17–21 m) wide but half as deep as conventional lots, allowing the developer to achieve densities upward of seven units per acre (17/ha). Wider lots add proportionately to street and utility costs but may yield greater curb appeal. Wide-shallow lots usually necessitate two-story houses. If the lots are less than 65 feet (20 m) deep, the back-to-back rear yards may be too small for privacy. Depths of at least 70 feet (21 m) are recommended.

Zipper lots are like wide-shallow lots except that space is borrowed from adjacent lots to avoid the problem of narrow, rectangular rear yards. Easements are used to make the rear yards of back-to-back houses abut on an angled, rather than parallel, property line. The main disadvantages of zipper lots are the complexity of the plot plan, loss of privacy from second-story windows that overlook the neighbor’s backyard, and possible resistance from buyers and government jurisdictions. Nevertheless, they offer a creative solution to high-density housing in selected markets.

With careful design, densities of seven to eight units per acre (17–20/ha) can be achieved in a single-family detached setting, and densities of 10 to 12 units per acre (25–30/ha) are possible for small senior housing units or projects without garages. Even higher densities have been achieved in traditional neighborhood developments.

Creative site planning and unit design make it possible to achieve greater densities without sacrificing privacy and livability. Increased densities are one tool to be used in solving the crisis of affordable housing in areas with high land costs. Community acceptance of higher densities is more likely if developers are careful to design attractive, livable communities that enhance their surroundings.

The major difference between the development of land and the development of income property is that land is usually subdivided and sold rapidly, whereas income property is usually held and operated over a period of years. The holding period is the key to deciding the appropriate type of financing. Land development is financed by a short-term development or construction loan, which is paid down as sales occur. Income property development is financed by both a construction loan and a permanent mortgage, the latter of which is known as a takeout loan. For income property development, the construction lender depends on the permanent lender to replace (take out) the construction loan with the permanent mortgage. For land development, the construction lender relies on the developer’s ability to sell the finished lots within the agreed-on time frame and at the projected price.

FIGURE 3-10 | Lot Yield Analysis for Different Zero-Lot-Line Configurations

Success in land development—and the developer’s ability to repay the development loan—thus depends on the successful marketing of the lots. Because no takeout exists for construction lenders, they must be satisfied that the developer will be able to sell enough lots fast enough to pay off the loan. Often, construction lenders require other collateral, such as letters of credit, in addition to a mortgage on the property. The amount of the loan is usually limited to 30 to 50 percent of the projected sale proceeds to provide a cushion in the event that sales occur more slowly than projected. Slower sales translate into greater interest costs because the balance of the development loan is reduced more slowly than the developer initially projected.

The most difficult task for beginning developers is obtaining financing. Most developers will need to convince lenders to provide them with financing. In most situations, developers must contribute equity and sign loans personally. A developer’s equity can be furnished in cash or in land. Suppose, for instance, that a developer purchased land for a project for $100,000 and the market value of that land after entitlement and planning rose to $400,000. If the total cost of the developer’s proposed project is $1 million ($600,000 for development costs plus the market value of the land), the developer could probably find lenders willing to lend 70 percent of that amount. In other words, the lenders require $300,000 equity. Because the market value of the land is $300,000 greater than the original land cost, the developer should be able to use the land equity to satisfy the lender’s requirement for $300,000. In fact, the loan would cover the developer’s original $100,000 land cost because the $700,000 commitment exceeds the development cost of $600,000 by $100,000.

PURCHASE MONEY NOTES. The terms of the purchase money note can play a vital role in financing the project. PMNs automatically have first lien position and must be paid off before the developer can get a development loan because the development lender must hold a first lien position on the land. If the developer can get the seller to subordinate the PMN to the development loan, however, it is possible to reduce or eliminate the need to raise outside equity—the hardest money for any beginning developer to obtain.

It is difficult, but not impossible, to find a seller who will subordinate the PMN. Beginning developers should look for sellers who do not need cash immediately and who are willing to accept the risk of subordination in return for more money. The developer should expect to pay a higher land price, higher interest rate on the PMN, or both in exchange for subordination. Because a subordinated PMN can be crucial for covering a beginning developer’s equity requirements, it may even be worth giving the seller a percentage of the profits as added incentive to subordinate. This arrangement merely recognizes what is already a reality: the seller is, by virtue of his loan, a secured partner in the deal.

Even with subordination, the developer will have to negotiate with the development lender to treat the subordinated PMN as equity. Subordinated or not, the PMN’s release provisions are among the most important business points for negotiation with the seller. The release provisions provide for removing designated subparcels of land as collateral from the PMN so the developer can give the development lender a first lien (where the PMN is unsubordinated) or a buyer can get construction financing to build a home.

The release provisions designate which subparcels of land are to be released from the first lien of the PMN. They have two main parts: (1) initial land release concurrent with the downpayment and (2) land released by future principal payments on the PMN. On larger tracts, the downpayment on the land provides for the release of the first subparcel the developer plans to develop. The land that is to be released first must be designated specifically in the purchase contract and the PMN mortgage to avoid any conflict or confusion. The unencumbered parcel provides the initial collateral for the development loan, although the developer may have to provide additional collateral, such as a personal guarantee, letter of credit, or other assets, including real estate. The development loan can be extended to cover other subparcels as they are released from the PMN, thereby providing construction money for development.

The land development contractor will be able to build improvements on only those parcels for which the development lender has a first lien. If the contractor begins work on any part of the land before the lender has perfected the lien (recorded it), the lender may halt construction until possible lien conflicts are cleared. Clearing lien conflicts can take several months because all suppliers who have delivered material to the property and all subcontractors who have worked on the property must sign lien waivers indicating that they have received full payment. If anyone is unhappy for any reason (a common occurrence in building), he may use the developer’s need for a signature on the lien waiver as leverage to get more money.

BUILDERS’ PRECOMMITMENTS. As part of the market feasibility stage, the developer obtains from area builders indications of interest in purchasing the lots. Next, the developer must secure commitment letters from builders, which are part of the documentation the developer will have to submit to the lender to obtain a loan commitment. The commitment letter specifies the number of lots each builder will buy in the project.

Ideally, the developer will have commitments for most of the lots on a site before approaching potential lenders. Although commitments help reduce the market risk, they do not guarantee that the lots will be sold unless they are backed by letters of credit (LCs). LCs provide guarantees to the developer that the builder’s unpaid balance on the lots will be paid off by the bank that issues the LC. If the developer intends to build on all the lots himself rather than selling to other builders, the financing may be more complicated. The lender would look at equity and financing needs for the entire project, including the buildings.

Builders, who are often underfinanced, are reluctant to guarantee that they will purchase the lots. The developer must convince his lender that builders’ commitments are solid or must provide proof with the LCs. The developer should know the type of documentation that lenders will require before talking to builders. If the lender requires firm commitments backed by LCs, then the developer must address that requirement as part of the deal with the builders.

BUILDERS’ PURCHASE TERMS. The purchase terms that builders require for lots vary according to local market conditions. Downpayments range from $100 earnest money to 10 percent—or even 20 percent—of the purchase price. Builders pay the earnest money when they reserve the lots. The balance is covered by a note that typically sets the interest rate beginning the day the developer delivers finished lots. The contract for purchasing lots usually defines lot delivery as the date on which the city accepts public street dedications or the engineer certifies that the project is substantially complete. The contract may actually stipulate a list of conditions that must be satisfied to convey the “finished” lot.

In slow markets and in workout situations (when the developer has defaulted on the loan), builders hold a stronger position than the developer. To generate interest from builders, developers sometimes subordinate to the construction lender some portion of the land note on builders’ model houses, allowing builders to reduce upfront costs, or they may provide seller financing to builders. Another approach that developers use to generate interest from builders in slow markets or workout situations is to discount the initial lots. For example, if the lots normally sell for $20,000, developers may sell the first two lots to builders for $10,000 and the next two for $15,000. Any of these concessions should be cleared well in advance with lenders and investors, and preferably presented as a marketing cost in the business plan. Unexpected sales concessions could cause the lender to review release provisions on the project, effectively revaluing the collateral value of the developed lots.

Developers of Ten Fifty B used public and private financing for an affordable high-rise community in downtown San Diego.

AFFIRMED HOUSING GROUP

TIPS FOR DEALING WITH LENDERS. Although each deal with a land development lender is unique, several guidelines usually apply:

• The developer should borrow enough money at the beginning of the project; the developer should not think that a loan can be renegotiated later or that lots can be sold faster.

• The developer should allow enough time on the loan to complete the project or to provide for automatic rollover provisions, even though the lender will charge for the rollover option.

• If working with a lender on multiple projects, the developer should consider that terms on one project may become open to renegotiation if progress on a second project is not to the plan.

• Typical points for the land development loan are two points up front and one point per year, starting in the third year. Points are calculated on the total loan request, not on the amount drawn to date. For example, two points on a $1.5 million loan request amount to $30,000.

• The loan can be structured as a two-year construction loan with three automatic renewals.

Development loans are a form of construction loan. The amounts by which the developer pays down the loan cannot be borrowed again later. If possible, developers should structure the development loan as a revolving line of credit that allows borrowing up to the maximum limit of the credit line, regardless of repayments already made. Doing so will likely require the provision of additional collateral as the lots are sold.

The development lender holds a first mortgage on the entire property and must release its lien on individual lots so that the purchaser (the builder or end user) can obtain construction financing. The release price is thus a major item for negotiation between the developer and the lender. The lender wants to ensure that the loan is paid off faster than the land is released from the mortgage, which protects his security in the event that the developer defaults on the loan. The developer, on the other hand, prefers that the release price simply be a prorated share of the development loan. For example, if the development loan is $1 million for 100 lots, the sale of one lot would retire the loan by $10,000 (1 ÷ 100 × $1 million). Most lenders set the release price at 1.2 to 1.5 times the prorated share (called the multiple). For a multiple of 1.2, the release price is 1.2 times $10,000, or $12,000 per lot. Thus, every time a lot is sold, the developer pays down the loan by $12,000. The lender often wants a high multiple, 1.3 or greater, for releasing lots. The developer wants a multiple as low as possible, 1.2 or lower, because he needs cash flow. In return for a low multiple, the lender may require some form of credit enhancement, such as an LC or second lien on other property. Particularly in developments with widely divergent lot prices, the lender may simply set release prices as a percentage of an agreed-on lot price list, but the same acceleration of loan repayment (a higher percentage) will be the lender’s goal.

In the cash flow analyses shown earlier in this chapter, the developer was assumed to own 100 percent of the deal, investing 100 percent of the equity and receiving 100 percent of the cash flow. The developer would also have 100 percent of the downside risk and liability. All or any part of a land development project, however, may be packaged as a variety of joint ventures.

The various legal forms of joint ventures are described in chapter 2. In this chapter, the business side of joint ventures is the focus. Most joint ventures involve three major points of negotiation for distributing cash flow from the venture:

1. preferred returns on equity;

2. priorities of payback of equity, fees to the developer, and cash flows from the venture; and

3. split of the profits.

In addition to dividing the spoils of the venture, the joint venture specifies how risk is shared between the parties—the timing and amount of equity contributions, fees to the developer and other parties, personal guarantees on notes, and management control of the development entity and other operating entities and associations (see chapter 6).

DEVELOPER AND LANDOWNER. One of the most common forms of joint ventures is that between a developer and a landowner. The land is put into the deal at a negotiated price; it is common that land value covers in full the equity that the developer may need to obtain development financing, although partners may demand some additional cash as “skin in the game.” The landowner may hold a purchase money mortgage subordinated to the development loan or a first priority for receipt of positive cash flow. The order in which cash flows are distributed (the order of cash distribution priorities) might be as follows if land value equals total equity:

• Priority 1—The landowner is returned the equity land value allowed by the lender.

• Priority 2—The landowner receives a preferred return (cumulative or noncumulative) on the equity (see chapter 4).

• Priority 3—The developer receives a development fee, some of which may be paid during the construction and leasing periods.

• Priority 4—The developer and the landowner split the remaining profits; priorities and fees are subject to negotiation.

When required equity is less than land value, the landowner gets some value out of the first loan draw. If equity is greater than land value, a two-tiered partnership provides for additional equity investment.

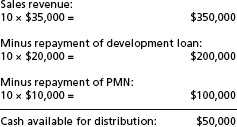

If the landowner has a subordinated PMN on the land, that loan agreement provides for releases similar to those in the development loan agreement. Both liens must be released before homebuilders or other buyers of the lots can obtain free and clear title, which they need to obtain construction financing. For example, suppose a subdivision has both bank financing and a subordinated PMN from the seller. Suppose also that the PMN calls for repayment of $10,000 to release a lot from the note and that the development loan calls for $20,000 repayment. If the developer sells ten lots that net $35,000 each, the cash flow would be

Most joint venture agreements provide for the venture to retain cash available for distribution as working capital until the development loan is retired. The cash provides a safety net to cover future equity needs in the event that sales slow or costs increase. Alternatively, such cash could be given to the landowner until the land equity has been fully recovered, or it could be considered profit and divided among the joint venture parties. The landowner would prefer, of course, to receive first priority on all cash flows until recovering the value of the land equity.

Sometimes, the revenue from land sales does not cover the required loan release payments for a given parcel or series of lots. In that case, the joint venture partners would be required by the partnership’s operating agreement to invest new equity to cover the deficit. The development loan agreement may require the lender’s approval for sales below a certain price, although the developer would prefer to have full control over pricing decisions. Such pricing approval, while common, can be a recipe for disaster if the lender withholds approval of lower prices to match current market conditions. A common middle ground is for the developer and lenders to agree on a base price, and an allowable maximum discount, which are preapproved and can be executed quickly by the sales team.

One benefit for landowners of putting their land into a joint venture is to save on taxes, especially when they have owned the land for a long time and their basis is well below the current market value. If they sell it outright, they must pay taxes immediately on the full capital gain. If they put it into a joint venture, they can defer paying taxes until the property is sold by the joint venture and capital is returned to them. A tax accountant should be brought into the negotiations early with the landowner to understand IRS requirements for “installment sales.” Taxes on the gain are paid as principal payments on the PMN are made. In a joint venture with a subordinated PMN, the principal payments are usually timed to occur when lots are sold to homebuilders or according to a prenegotiated schedule (typically three to ten years), whichever comes first. For example, suppose land originally purchased for $100,000 is put into a joint venture at the current market value of $1 million, with a PMN for $750,000. One-quarter of the $900,000 gain is taxed initially because the downpayment is one-quarter of the sale price—$250,000 of $1 million. The rest of the gain is paid as the PMN is retired. Note that this structure works with any PMN, even if no joint venture is created with the land seller. Taxes are deferred longer, however, if the PMN is subordinated. If it is unsubordinated, it must be paid off as soon as the developer obtains a development loan.

DEVELOPER AND INVESTOR. Joint ventures between the developer and third-party investors are far more common than joint ventures with the landowner. The third-party investors (third party because they are not involved in the original transaction) furnish the cash equity needed to complete the deal. For example, in the deal shown above between developer and landowner, the developer purchases the land outright from the land seller. The investors put up the cash needed to purchase the land, which was the landowner’s equity in the first deal. The developer’s arrangement with the investors might closely resemble the deal with the landowner with respect to priorities for cash distribution:

• Priority 1—All cash available goes to investors until they have received their total cash investment (return of equity).

• Priority 2—The next cash available also goes to the investors until they have received, say, an 8 percent cumulative (or noncumulative) return on their investment (return on equity).

• Priority 3—The next cash available goes to the developer until the agreed fee is reached.

• Priority 4—All remaining cash available is divided between the developer and the investors based on the agreed-on terms and conditions. (With institutional investors, multitiered “waterfall” provisions are more common.)

Every term of the deal is negotiable, including the order of priorities and the amount of personal liability on the development loan. A straightforward 50/50 split between the developer and the investors, without any priorities, used to be typical and some large developers still use this format, but beginners typically must give a larger share to investors to attract their interest. In the case of a 50/50 split with no priorities, developers are able to take out profit as each acre is sold. The risk to investors is that developers may sell off the prime tracts, take the profit, and then fail to sell off the balance of the project, leaving the investors with a loss. Most investors, therefore, insist on receiving all their equity before developers participate in any profit. Until this milestone is achieved, compensation for developers may be structured as a percentage of net proceeds, and reimbursement of professional fees for work performed on the project.

DEVELOPER AND LENDER. Some lenders provide more favorable debt financing for a deal—a higher loan-to-value ratio, for example, or lower initial interest rate—in exchange for some percentage of the profits in the form of a participating loan. In this structure, all the deal financing might be structured as debt, but the loan is convertible at various points to a predetermined amount of equity: the “equity kicker.” For the developer, this arrangement is the easiest form of joint venture because it involves only one other party. The lender can structure involvement in a variety of ways. The financing can be considered a 100 percent loan, or some portion can be considered equity. The difference between a 100 percent loan and, say, an 80 percent loan with 20 percent equity is that the equity portion usually receives a “preferred return” rather than “interest.” The preferred return is paid when cash is available, whereas interest must be paid immediately. Some development loans have accrual provisions that allow interest to be accrued in a fashion similar to that for preferred returns. They allow the project to accrue unpaid interest into future periods until cash is available to pay it. The split with inexperienced developers could be 65/35 or 75/25, with the lender receiving the larger share. Joint ventures with lenders usually allow developers to receive a fee for administrative expenses. Developers may request fees of 5 to 10 percent of construction costs, but 3 to 5 percent is more common.

The construction phase of land development consists primarily of grading the land and installing drainage systems, streets, and utilities. Land development involves fewer subcontractors than building construction, but the process can be just as complicated, not least because of the role played by the public sector. The facilities built by land developers are usually dedicated to the locality to become part of its urban infrastructure. The locality maintains the streets, and the utility company, which may also be a city agency, maintains water and sewer lines. Consequently, all facilities must be built in strict accordance with utility company standards; city, state, and federal codes; and management practices.

If possible, the contractor should be part of the development team from the beginning. Even if developers select a contractor after plans and specifications are completed, they should go over preliminary plans with a construction manager who can offer money-saving advice for various aspects of the design layout. The following tips are useful in dealing with general contractors:

• Negotiated-price contracts are usually better than competitively bid contracts. On smaller jobs, developers should negotiate with two or three qualified contractors simultaneously and take the best deal.

• A fixed fee for the contractor of, say, $5,000 to $10,000 for a $100,000 to $200,000 job (costs based on actual dollars spent, verifiable by audit) is recommended. For change orders, developers should pay the contractor the additional cost but no additional fee or markup. Equipment should be charged based on direct time in operation.

• Developers should hire a member of an engineering company for which business currently is slow to be on site to check that everything is installed properly. Developers should not rely solely on the engineer’s certification and should ensure that the engineer will spend enough time on site. The engineer of record (responsible for the original drawings) should certify the work (check progress at least twice per week), but the on-site engineer should check that everything is installed properly and should be present for deliveries and for any event that requires quantity surveying to price, such as remedial fill for inadequate subgrade. An engineer should also be present for any visits by inspectors, who should arrange their visits with the engineer.

• The standard 10 percent retention of payment for subcontractors is recommended. Subcontractors should sign lien releases and bills-paid affidavits with every request for a draw. The general contractor must obtain these affidavits and releases from the subcontractors and suppliers before paying them.

• If the contractor is not performing satisfactorily, developers should notify the contractor in writing (by registered mail), citing the specific paragraphs of the contract that are being violated and stating the possible consequences if performance does not improve by a certain date.

• When hiring a general contractor to construct forsale housing, developers should include a clause stating that any deceptive trade practice suits that are not warranty items belong to the general contractor, not the developer.

Key Points on Contracting

Contracts are necessary for controlling costs, scheduling, and performance of those involved in a project. It is important to get everything in writing. Contracts are a commitment. Once signed, it is difficult to backtrack.

THE CONTRACTING PROCESS

• Bidding

• Assembly of bid package contents

• Prebid meetings

• Bid review and award

• Review of bidding issues and ethics

• Review of other issues

CONTRACT CONTENTS

• Details of commitments

• Behaviors agreed to that benefit and bind future managers

• Firm commitments versus general understandings (represents a meeting of the minds; words on paper must reflect intention of parties and needs involvement of principals)