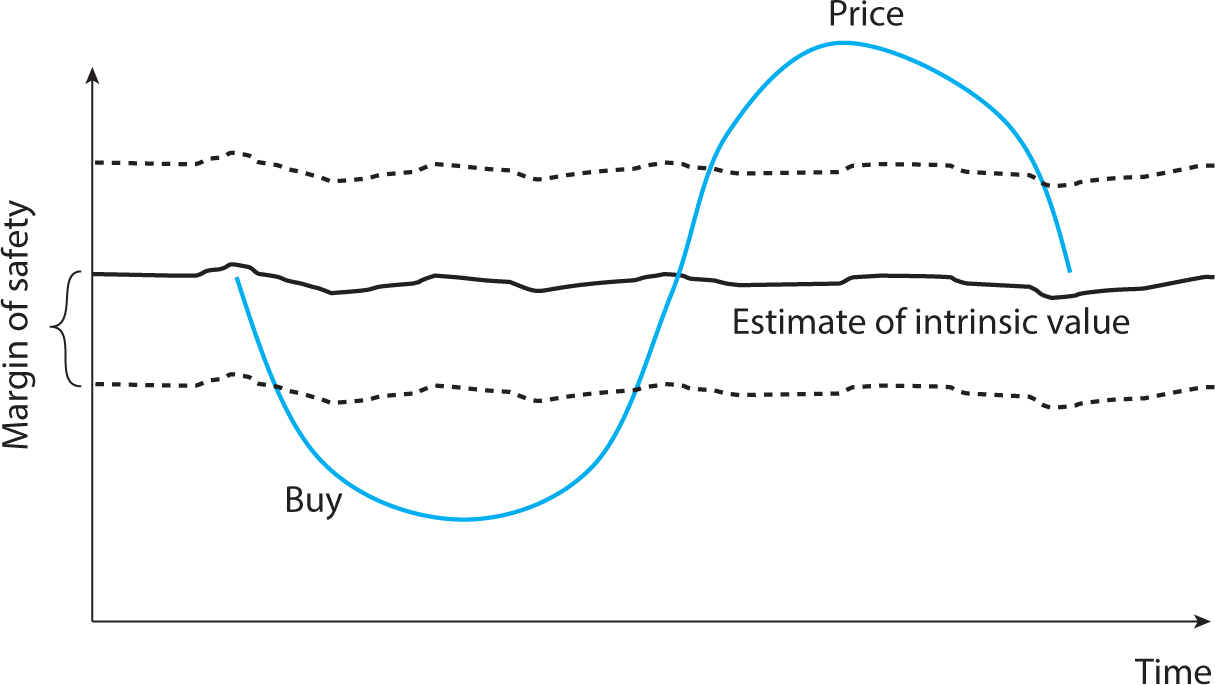

Figure 7.1. The margin of safety.

Discretionary Equity Investing

Investment is most intelligent when it is most businesslike…. if a person sets out to make profits from security purchases and sales, he is embarking on a business venture of his own, which must be run in accordance with accepted business practices if it is to have a chance of success…. The first and most obvious of these principles is … “know your business” … A second business principle: “Do not let anyone else run your business, unless (1) you can supervise his performance with adequate care and comprehension or (2) you have unusually strong reasons for placing implicit confidence in his integrity and ability” … A third business principle: “Do not enter upon an operation … unless a reliable calculation shows that it has a fair chance to yield a reasonable profit. In particular, keep away from ventures in which you have little to gain and much to lose.” … A fourth business rule is more positive: “Have the courage of your knowledge and experience. If you have formed a conclusion about the facts and if you know your judgment is sound, act on it—even though others may hesitate or differ.”

—Benjamin Graham (1973, pp. 286–287)

Most active equity investors trade based on discretionary judgment, and many of the most successful ones swear to the principles of Graham and Dodd (1934) and Graham (1973). As is clear from the quote above, this means thoroughly analyzing a firm’s business and its future profit potential, considering whether the management has the ability to deliver on this potential and the integrity to pay the profits out to shareholders, valuing the firm in relation to its price, and acting on your judgment even if it goes against conventional wisdom.

The hedge funds that use these strategies are called long–short equity funds. Long–short hedge funds seek to buy excellent stocks that trade at a discount and to short-sell bad stocks that are overvalued. They are often more long than short, perhaps because it is easier to find and implement long investments and because they may also want to earn the equity premium. Some long–short equity hedge funds are specialized in a certain area. For instance, some funds specialize in a particular industry (consistent with Graham’s “know your business”), e.g., technology stocks, healthcare stocks, or commodity-related stocks. Other long–short hedge funds specialize in value investing or growth investing. The large long–short equity hedge funds are often broad, but they might consist of several specialized teams.

Discretionary equity investing is also used by active mutual funds, pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, and other traders. The main difference is that many of these investor types are long only. Hence, they will not just buy the stocks that they like, they will also overweight them relative to the benchmark, and, while they cannot short-sell stocks, they can underweight them relative to the benchmark or avoid them altogether. However, since most stocks are a very small percentage of a benchmark (often less than 1%), avoiding a stock has a much smaller effect than buying a significant position. Said differently, the short-sale constraint is often binding, so these investor types usually focus on finding good stocks rather than finding bad ones.

7.1. VALUE INVESTING

Value investing can be defined simply: it is the investment strategy of buying securities that appear cheap while possibly short-selling securities that appear expensive. The idea of value investing goes back at least to Graham and Dodd (1934). Value investing is harder than it sounds. Stocks are often cheap because there is something about them that makes investors uncomfortable, and stocks are often expensive because lots of investors love them. Value investing means going against conventional wisdom, which is never easy, avoiding (or shorting) stocks that most people love and buying those that are out of favor. Value investing takes courage, as seen from Graham’s final principle in the introductory quote.

There are of course many ways to implement the general idea of value investing. The implementations of value investing differ in their definition of the intrinsic value, the typical holding period, and how the portfolio is constructed. Some value investors are patient and seek to hold their positions for the long term. They seek to buy a stock for less than the value of the future dividends that they will collect over time. Other value investors seek to buy a cheap stock and sell it over the medium term as they hope the pricing of the stock corrects itself.

One simple example of a value trade is to buy shares in a company with a lower market value than its cash holding and no debt—if you can find such a company. Is this trade a sure profit? Not if the market value is low because investors foresee that the company’s management will waste the cash such that shareholders never benefit (see also Graham’s second business principle). In this case, the value investor must be more active to profit from this trade, e.g., by buying enough shares to influence the management to pay out the cash as a dividend or use it productively.

Another simple implementation of value investing is to buy stocks with a high book value relative to the market value. Historically, even this very simple value strategy has been profitable, as we discuss further in chapter 9, on quantitative equity investing.

Fundamental Analysis

Value investors spend a lot of time on—you guessed it—valuation. They estimate the value of a stock using the dividend discount model in one form or another (e.g., the residual income model) as discussed above, but the difficult thing is to find the inputs to the model, not to plug them in. The process of estimating the inputs in the dividend discount model is called fundamental analysis.

Value investors project earnings into the future, e.g., by considering future sales growth, the evolution of the size of the overall product market in which the firm is operating, the firm’s potential future market share, how profit margins will evolve based on the competitive advantage and the growth of costs, efficiency gains, and so on.

They try to figure out the best estimate of the intrinsic value in all kinds of ways. Some focus on the numbers, others on the people, yet others on the industry dynamics. The value investors who focus on the numbers analyze the accounting statements in detail, consider the evolution of the historical accounting numbers, and forecast future free cash flows.

Other value investors focus on the people, talking to the management of the firm and everyone involved in its business, such as employees, unions, customers, suppliers, and competitors. Based on these discussions, the investor seeks to determine whether the firm is well run; whether the customer base is happy, loyal, and growing; whether the firm is in a favorable competitive position; and whether costs can be controlled.

Yet other value investors focus on the industry dynamics, often specializing in a single (or a few) industries. They try to determine who is dominating an industry and whether this domination is sustainable. Which firms have the strong brand names, and who can be really profitable? Are there barriers to entry in the industry, and how easily can customers change between firms? What are the major changes that will transform the industry, for instance, technological changes, and who will benefit vs. suffer as a result of these changes? Which firms are making the key innovations, and how easily are these copied by others? How is the market share between different types of players changing?

Whereas these questions relate to the dynamics within an industry, other equity investors bet on entire industries, going long on several stocks in the same industry (or an industry index) while shorting stocks in another industry. Such investors consider which industries are about to rise or fall based on, for instance, how the macroeconomic environment will affect the various industries. This investment strategy is sometimes called “industry rotation” or “sector rotation.”

Margin of Safety

When the future profits have been estimated, the value investor seeks to determine what these future profits are worth today. This is done by discounting the profits as per the dividend discount model. The value investor finally compares the estimated intrinsic value to the market value. The estimated intrinsic value is naturally sensitive to the inputs, not least to estimates of the discount rate and to growth rates. Hence, value investors often consider a range of possible estimates of the intrinsic value to consider how robust their valuation is.

We must recognize, however, that intrinsic value is an elusive concept. In general terms it is understood to be that value which is justified by the facts, e.g., the assets, earnings, dividends, definite prospects—as distinct, let us say, from market quotations established by artificial manipulation or distorted by psychological excesses. But it is a great mistake to imagine that intrinsic value is as definite and as determinable as is the market price.

—Graham and Dodd (1934)

Graham and Dodd (1934) therefore recommend that value investors use a margin of safety, that is, leave some room between the market value and the best estimate of the intrinsic value. This is illustrated in figure 7.1, which shows a stylized time series of a stock’s price and intrinsic value. The uncertainty about the intrinsic value is indicated by the dashed “error bands” around the value, and the margin-of-safety principle means that the value investor should only buy when the price drops below the lower band.

Figure 7.1. The margin of safety.

“Deep” value investors go for stocks at really bargain basement prices. When you buy a stock with a very low price, for instance, a low price-to-book value, then you must always ask the following important question: Does the stock look cheap because it is cheap or because it deserves to be cheap? Said differently, is this stock a diamond in the rough, a cheap company that other investors somehow fail to recognize? Or, does the stock only appear to be cheap because its true fundamentals are collapsing?

I could give you other personal examples of “bargain-purchase” folly but I’m sure you get the picture: It’s far better to buy a wonderful company at a fair price than a fair company at a wonderful price.

—Warren Buffett, Berkshire Hathaway Inc., Annual Report, 1989

Since a stock’s price is the outcome of trading among thousands of people, many of them smart and successful, its price reflects a lot of information. Hence, if a stock looks cheap, there is often a reason, meaning that its growth is likely to be sub-par. The risk that a value investor ends up owning fundamentally flawed companies is called the value trap. For example, a bank stock may be low because the market recognizes that the bank will have to write down many of its loans. As another example, a stock can look cheap because the market realizes that the firm is subject to a lawsuit that will be very costly.

More broadly, consider a stock with an unusually low price-to-book P/B value (relative to the historical values of similar firms). Hence, by this measure, the stock looks cheap. Suppose further that you believe that the P/B will normalize over time. Does this mean that you expect to make money by buying this stock? Not necessarily—it depends on what is going to adjust, the price or the book value. If the mean-reversion of P/B is driven by a rising price, then the value investor makes money. However, the value investor may lose money if the mean-reversion of P/B is driven by a falling book value—this means that the stock experiences negative earnings that make it live up to the market’s low expectations.

Investing based on P/B has been profitable on average historically, but many bets have led to losses because of the value trap. The value trap can be mitigated, at least partially, by focusing on a stock’s quality characteristics, as we discuss next.

7.2. QUALITY INVESTING AND QUALITY AT A REASONABLE PRICE

One side of value investing is to look at the price of what you buy, and the other is to look at the quality. Said simply, quality investing means buying “good” companies. Quality investing can be combined with value investing, which can be called “quality at a reasonable price” (Asness, Frazzini, and Pedersen 2013).

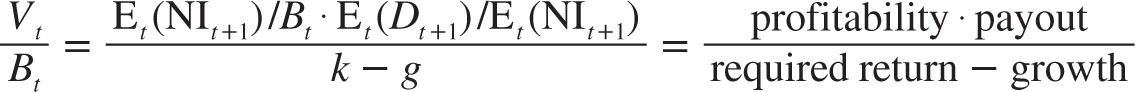

What is a “good” company, that is, a high-quality company? Quality can be defined as characteristics for which investors should be willing to pay a higher price. Based on the dividend discount model, high quality means a high present value of future free cash flows. However, there can be many quality characteristics that can help predict future free cash flows. Following Asness, Frazzini, and Pedersen (2013), we can classify a stock’s quality characteristics in four broad groups based on their version of Gordon’s growth model:

The left-hand side is the intrinsic value of the stock divided by its book value. We divide by book value as a normalization because otherwise differences in stocks’ equity values would be mostly driven by size.

The right-hand side of the equation shows the main quality characteristics, namely those that justify a higher valuation multiple. Here, profitability (or return on equity) is defined as the profits (measured as net income, gross profits, or otherwise) per unit of book value, Et(NIt+1)/Bt. Payout is defined as the fraction of the profits that are paid out to shareholders, Et(Dt+1)/Et(NIt+1). As above, g is the growth in profit and k is the discount rate. This way of looking at equity valuation shows that investors should be willing to pay a higher price multiple for stocks with higher growth, higher profitability, higher safety (i.e., lower required return k), and higher payout ratio.

Believers in market efficiency would agree that it is possible to identify high-quality firms, but market efficiency implies that such firms have high prices and normal returns (relative to the risk) going forward. In other words, believers in market efficiency think that high-quality firms are no better investments than low-quality firms because the market prices already reflect the quality.

In contrast, quality investors believe that it pays to identify high-quality firms since the price does not always fully reflect the quality and, therefore, the future returns are high on average. Let’s discuss how quality investors trade on each quality component, namely growth, profitability, safety, and the payout ratio.

Growth: Good Growth vs. the Growth Trap

Many investors are searching for growth stocks, seeking to find the next Google, the next Apple, or the next Microsoft. Certainly, most people have heard stories of trades returning many times the original investment, and such stories are often centered around early investments in growth companies. However, stocks offering a growth dream and little current profitability can be speculative and overvalued, especially if investors project the growth too far into the future. A growth firm is only a good investment if the growth is not fully reflected in the market price.

Another pitfall to consider when investing in growth stocks is that not all types of corporate growth are value enhancing. Good growth is sustainable growth in profits that leads to growth in free cash flows. Bad growth is growth in other numbers that ultimately hurts profits.

One form of bad growth is growth in assets driven by an empire-building manager who wants to increase the scale of the firm to grow her own power and compensation, e.g., through expensive acquisitions or careless expansion. Another form of bad growth is sales growth driven by very low product prices, leading to deteriorating profit margins. Bad growth can also come in the form of temporarily improving accounting numbers by using accounting tricks that are not just unsustainable but will in fact later need to be reversed.

To see the difference between good and bad growth, consider two chains of retail shops with strong sales growth. One has increased its sales with “same-store sales growth,” that is, it has increased sales in its existing shops, kept expenses constant, and increased profit margins. Clearly such same-store sales growth is good. The other retail chain has also increased sales, but this has been accomplished by buying up other retailers at premium prices. Such a strategy of asset growth, not profit growth, can often be flawed and can hurt shareholder value unless the acquisitions have special synergies or are done at very favorable prices.

Profitability and Earnings Quality

Clearly a more profitable firm is more valuable than a less profitable (or unprofitable) one. Profitability can be measured in several different ways, ranging from the reported earnings number, to measures focused on cash flows, to the “top line” gross profits (revenues minus cost of goods sold).1 Equity investors seek to determine a company’s ability to continue to make true economic profits in a sustainable way. They also look at a company’s “earnings quality,” meaning how reasonable a company’s accounting practices are. Indeed, a company can choose to report its business activities in different ways, such as being more or less aggressive in moving items off the balance sheet, pushing expenses into the future, or recognizing revenues early using so-called accruals. Clearly, equity investors prefer a stock with higher true profits to one with similar apparent profits generated by accounting adjustments.

Safety

A third measure of quality is safety. Investors should have a lower discount rate for safer stocks and thus be willing to pay a higher price for them, when everything else is equal. Safety can be measured using stock returns and fundamental accounting variables, or both. The standard return-based measure is the market beta, measuring the systematic risk that the stock price will go down when the market is also down. Some equity investors also look at a stock’s total volatility (or even its idiosyncratic volatility). The beta is relevant for measuring the contribution to risk in a very well-diversified portfolio, while the stock’s total volatility is the risk of holding the stock in a concentrated portfolio. Fundamental risk measures are designed to estimate the risk of declining future profits, for instance, by considering the past variation in profitability.

Payout and Management Quality

A fourth class of quality measures focuses on how shareholder-friendly the firm is and how well managed it is. Specifically, one can look at whether profits are paid out to shareholders as dividends or share repurchases or how they otherwise benefit shareholders. In other words, does the firm’s management seek to maximize shareholders’ value or to extract private benefits for itself? For instance, some managers focus on generating cash for lavish perks, such as corporate jets, rather than for shareholders. Also, some managers act as “empire builders” who go on sprees of expensive acquisitions rather than focusing on profit growth. A sign of poor management can be that the board is packed with cronies rather than independent board members who can add value to the firm and represent the shareholders’ interests. Another sign can be that the management is entrenched with a corporate governance that makes it very difficult to take the firm over by outsiders.

Of course, aside from the managers’ dedication to creating value for shareholders, the quality of management more broadly is important. Investors consider whether the management has insightful and value-creating visions for the company’s growth, is able to inspire and motivate employees, can cut costs, and can aim for sustainable long-run growth. Some investors seek to buy stocks with good management, others seek to buy stocks that are cheap due to poor management and then profit from improving it—this attempt to directly influence the management is called activist investing, as discussed further in section 7.5.

Value investors and growth investors are often thought of as polar opposites, and sometimes they are, but at other times, they end up buying the same stocks. Figure 7.2 shows why they are often thought to be opposites. The worldview of a deep value investor, a “bargain hunter,” is depicted on the top. This bargain hunter has estimated his view of the intrinsic value, which stays relatively constant over time even as the market price bounces around. Therefore, the stock will tend to look cheap to the bargain hunter when the price has fallen and this is when he will buy. Later, when the price has gone up, the stock might start to look expensive to the bargain hunter and he might therefore decide to sell.

Figure 7.2. The worldviews of bargain hunters vs. growth investors.

Panel A: Worldview of a bargain hunter.

Panel B: Worldview of a growth investor.

The worldview of a growth investor is depicted in the bottom panel of figure 7.2. The growth investor is trying to buy a high-growth stock with a chance of becoming the next home run. A firm that is expected to experience fast growth in the future often has already experienced growth and good news in the past and, therefore, its price has likely been on the rise. Hence, whereas the bargain hunter might be selling stocks that have been rising in value, the growth investor might be buying such stocks. Ironically, they may both feel that they act as value investors, but their views of intrinsic value are very different. The bargain hunter is (perhaps implicitly) thinking of the intrinsic value as stable, whereas the growth investor perceives that the intrinsic value has risen even faster than the price.

Who is right? Surprisingly, they may both be right on average. Historically, people who buy stocks that look cheap in the sense of having a low price-to-book value have done well. The opposite stocks—those with high price-to-book, sometimes called growth stocks—have consequently underperformed. However, if one sorts stocks based on certain measures of their actual growth (rather than sorting on price-to-book), then high-growth stocks have outperformed low-growth stocks. In other words, high-quality stocks have outperformed low-quality stocks, and this holds not just for growth, but also for profitability, safety, and payout/management. Given that both value investing and quality investing work, one can do even better by combining these concepts. Some equity investors seek to buy growing firms that are cheap relative to the expected growth, which is called “growth at a reasonable price” (GARP) investing. This concept can be generalized to “quality at a reasonable price” (QARP) investing, namely the strategy of buying high quality at a discounted price.

7.3. WARREN BUFFETT: THE ULTIMATE VALUE AND QUALITY INVESTOR

Warren Buffett has become one of the world’s richest people based on his investment success over the past half century. How large a Sharpe ratio does it take to become the richest person in the world? Most investors guess that Warren Buffett must have realized a Sharpe ratio well north of 1 or even 2, perhaps based on Sharpe ratios promised by aggressive fund managers. The truth is that Buffett’s firm Berkshire Hathaway has delivered a Sharpe ratio of 0.76 from 1976 to 2011. While this is lower than some might have expected, it is nevertheless an extremely impressive number. Buffett’s Sharpe ratio is double that of the overall stock market over the same time period, which means that Buffett has delivered twice as much return per unit of risk. While some stocks or funds have clearly delivered higher Sharpe ratios over a shorter time period (which could be just luck), Buffett’s Sharpe ratio is the highest of any U.S. stock or any U.S. mutual fund that has been around for at least 30 years.2

How has Buffett done it? Buffett is known as the ultimate value investor, but just controlling for his value exposure does not explain his alpha. However, if we also control for his focus on quality stocks, then a large part of his performance can be explained. Said differently, Buffett has been buying cheap, high-quality stocks, and such stocks have performed well in general, which helps explain Buffett’s success. This finding is consistent with Buffett’s own statements:

Whether we’re talking about socks or stocks, I like buying quality merchandise when it is marked down.

—Warren Buffett, Berkshire Hathaway Inc., Annual Report, 2008

Another reason behind the magnitude of Buffett’s success is his leverage. He has not only delivered a high Sharpe ratio, he has also delivered much higher absolute returns than the overall stock market, on average beating the risk-free rate by 19%, about three times the overall stock market’s excess return of 6.1% per year. Berkshire’s volatility of 25% is significantly higher than that of the market, in part because Buffett has leveraged his equity investments about 1.6-to-1.

Buffett’s leverage comes from several sources. First, Berkshire has issued highly rated bonds at low yields, enjoying a AAA rating from 1989 to 2009. Second, Berkshire has financed about a third of its liabilities with its insurance float at an average cost below the risk-free rate. To understand this usually cheap and stable source of financing, note that Berkshire operates insurance and reinsurance companies and, when these companies sell insurance, they collect the premiums up front and pay a diversified set of claims later, which is like getting a loan. The efficiently run insurance firms both make a profit and help finance Buffett’s investments. Third, Berkshire’s liabilities also include deferred taxes (essentially an interest-free loan) and derivative contract liabilities.

7.4. HOLDING PERIODS AND CATALYSTS

Some managers buy a cheap stock with the idea of holding it for the long term. In this case, it is less important how the stock price evolves in the short term (assuming that the leverage is modest and investors do not flee). Warren Buffett sometimes takes this idea to the extreme, seeking an infinite holding period:

when we own portions of outstanding businesses with outstanding managements, our favorite holding period is forever. We are just the opposite of those who hurry to sell and book profits when companies perform well but who tenaciously hang on to businesses that disappoint. Peter Lynch aptly likens such behavior to cutting the flowers and watering the weeds.

—Warren Buffett, Annual Report, 1988

There may be several reasons for this approach. First, as Buffett and Lynch point out, many investors often sell winners too quickly and hang onto losers, a phenomenon called the “disposition effect.”3 In Berkshire Hathaway’s case, there might also be tax reasons since realizing capital gains would lead to taxes, which can be postponed forever as long as the holding period is forever.

On the other hand, many equity investors find it optimal to sell a stock when they think that its price has converged to its fair value or it has become expensive. Such investors view their capital as limited and want to apply that capital where its return is the highest. Hence, when a stock is no longer a great deal, they will reallocate capital to more promising investments. A common saying among traders is: “Don’t get married to your position.” This saying means that one should always look for the best current investments, regardless of what existing positions one happens to have, and one should not continue to hold a bad stock for fear of recognizing an error or reluctance to take profits.

Many equity investors are not only happy to take profits, they are very impatient for this to happen. Very impatient investors only buy a cheap stock if they also anticipate that a “catalyst” will make the stock price rise within a limited time horizon. Such value-and-catalyst investors seek to find cheap stocks that are about to get richer because the market is about to realize that stock’s potential. For instance, if the next earnings announcement by a firm with a cheap stock will reveal that it is on a strong new course, then you have a catalyst.

Some impatient investors go even further, seeking to create a catalyst. For example, suppose that a hedge fund has discussed a hotel company with several of its large investors and determined that the investors appear to be overly optimistic about the prospects of the company. Placing an investigator outside of the main hotels, they determine that the hotel is largely vacant and that earnings will disappoint—so the hedge fund sells the stock short. Rather than waiting for the other investors to learn this bad news at the next earnings announcement, the hedge fund might issue a report that details their negative assessment, hoping that the stock price will drop immediately—i.e., creating their own catalyst.

7.5. ACTIVIST INVESTING

Another way to create a catalyst is to engage actively in a discussion with the firm’s board, as activist investors do. Activist investing means buying shares in a company that could be worth more with better management and then trying to affect the decisions of the firm. When an investor has bought more than 5% of the shares in a U.S. stock, he must make a so-called “13D filing,” where he reports his position size and declares whether he intends to be active. The mere presence of an activist investor can send a message to management to get their act together. Furthermore, the activist investor may make specific suggestions to the management or board, e.g., by sending a letter suggesting a replacement of the management, changing certain board members, giving cash back to shareholders, cutting costs, or selling assets that are worth more elsewhere and focusing on the remaining firm. The activists can also try to get more direct influence by seeking a seat on the board, engaging in a “proxy fight” (i.e., creating a referendum on a specific proposal, e.g., at the annual meeting, where shareholders can authorize someone to act as their proxy and vote their shares), or trying to take over the company.

7.6. TRADING ON FLOWS AND SENTIMENT

Rather than looking at a stock’s fundamental value and quality characteristics, some equity investors focus on technical drivers of price changes based on order flow or try to anticipate investor sentiment. Large orders can move prices because they may reflect information or because liquidity providers must be enticed to take the other side of the trade. Hence, if a trader can predict that a large order will hit the market, e.g., a large buy order from a pension fund, then they may try to trade ahead of this flow. In other words, they may try to buy before order flow pushes price upward, although such “front-running” can be illegal, especially if done by a broker who takes advantage of information about its clients. Alternatively, a trader might try to take advantage of the subsequent price reversal, short-selling the stock when its price has been pushed up in order to profit as the price comes back down—as opposed to front-running, this trading activity actually helps the pension fund, which sends the large order because it reduces the price impact.

Some hedge funds buy a stock even if they think it is overvalued, betting that the stock is about to get even more expensive. Some investors claimed to pursue this strategy during the Internet bubble of the late 1990s, for instance.4 This form of trading activity contributes to price bubbles. It is based on the so-called “greater fool theory,” meaning that the investors may acknowledge that it is a foolish stock to buy, but this is fine as long you can sell at an even higher price to a greater fool. Of course, this activity cannot go on forever; bubbles eventually burst, and it is hard to predict when, so this is a risky strategy.

A clearly illegal form of trading seeks to push others to become greater fools, namely “pump and dump” schemes, where a trader might buy a stock and create a hype around it to drive the price up. Such price manipulation hopefully only exists in small corners of the market because of regulation and because competitive forces in the liquid securities markets make such schemes difficult and unprofitable.

7.7. INTERVIEW WITH LEE S. AINSLIE III OF MAVERICK CAPITAL

Lee S. Ainslie III is the managing partner of Maverick Capital Management, LLC, an investment management firm focusing on global equities. Before founding Maverick in 1993, Ainslie was a managing director of Tiger Management Corporation, the famous hedge fund founded by Julian Robertson, which gave rise to several successful “Tiger Cub” funds of which Maverick is one of the most prominent. Ainslie received a B.S. in systems engineering from the University of Virginia and an M.B.A. from the University of North Carolina.

LHP: How did you get started as an investor?

LA: I have been fascinated by stocks ever since I became a member of a high school investment club when I was in eighth grade in Virginia. After engineering school, I went to business school, and Julian Robertson was on the board of that school. I was fortunate to be asked to work with the board on a couple of issues, and as a result I got to know Julian. Occasionally, we would discuss stocks, and to my pleasant surprise one day he asked me to consider working at Tiger. That was my introduction to the hedge fund business.

LHP: Great. What is your investment process?

LA: To oversimplify, we are really trying to look out two or three years in every industry in which we invest, trying to identify who’s winning and losing, and, perhaps most importantly, recognize the discrepancies between our view and the view of the markets.

We have a very deep and thorough process. I think we’re unusual in that our typical ratio of primary positions to investment professionals is roughly four to one, which allows an uncommonly deep level of due diligence. Our process is less about suddenly recognizing a new potential investment that we then investigate, but rather more about constantly updating our strategic views of every industry in which we invest and looking for changes in that competitive landscape that may present new opportunities.

LHP: Can you give some examples of what you might be looking for in a company? What are some characteristics you like to see in a long position, let’s say?

LA: First and foremost, we focus on the quality of management. We work hard to evaluate the management team’s desire to create shareholder value, their competitive drive, their intellect, and ability to execute. Management is top of list.

Second is the quality of the business. This includes the persistence of cash flow streams, the drivers and sustainability of growth, and a strong understanding of the competitive dynamics within an industry. It may sound cliché, but we invest a great deal of time talking to competitors, suppliers, and customers—as well as interacting with as many members of management throughout different divisions and different locations around the world as we can.

Finally, valuation. I think part of the art of being a successful investor is to be very comfortable with a number of different valuation methodologies and to recognize which approach is the most appropriate or most meaningful in a different circumstance. Having said that, the most common valuation metric at Maverick is the comparison of sustainable free cash flow to enterprise value.

LHP: How do you know if a company’s favorable characteristics are already in the price?

LA: Well, I’m not sure we ever really know for sure, but by talking to folks on both the sell-side and buy-side we try to develop an understanding of consensus expectations. Often valuation itself can give real insight into true expectations as well. And, as mentioned, we try to understand the discrepancies between our view and the view of the market. Just ten years ago, developing a decent understanding of consensus estimates was rather straightforward, but it’s not nearly as simple today. So we invest a lot of time to develop a thoughtful view of the intrinsic value of a company and then compare and contrast our perspective to how the market is valuing different companies.

LHP: Which perspective is more useful: To try to estimate a company’s performance over the next year or two—say, the next earnings announcement—and compare one’s view to the expectation in the market vs. estimating the stock’s overall fundamental value and comparing it to the market price?

LA: It’s certainly important to be attuned to short-term expectations as well. For companies in which we invest, we try to have a strong understanding of what investors are expecting each quarter for a number of different key metrics. However, we are typically much more focused on looking out over the next several years and far less concerned with short-term results. Trading around quarterly results is just not what our research process is geared towards. We need to be attuned to short-term results just to avoid short-term mistakes, but I believe we’re much more likely to be successful on a consistent basis by understanding how longer term competitive dynamics will play out. In our way of thinking, the odds of making the right investment decision improve the further out we look.

LHP: For short positions, are you there just looking at the opposite of what’s a good long position or are there different types of things you look for?

LA: A bit of both. For most of our shorts, the investment process is essentially a mirrored process of what we’re doing on the long side. We’re looking for some combination of unsustainable fundamentals, incompetent management teams, or illogical valuations—preferably all three! We also have a bucket of really idiosyncratic shorts, for instance, we occasionally find companies that we believe have materially misrepresented themselves.

LHP: How do you assess when is the right time to buy and when is the right time to get out of the position?

LA: It’s purely driven by the discipline of making sure our portfolio is always focused on the opportunities we judge to be the most attractive. In the utopian world, every single day we would consider the return we think we can achieve in every one of our positions, how much risk we need to take to achieve that return, and how that risk-return profile compares to every other investment opportunity that we have. So if something is being bought or sold, that typically means we have concluded that another investment is more attractive at that point in time than a current investment. Of course, this is all easier in theory than in practice, but that’s our mindset.

We are very focused on looking forward, not backwards. At what price we have previously bought or sold a security should not be relevant to our evaluation of the attractiveness of that stock from current prices.

This approach of exiting a position when it is no longer as compelling as other opportunities means that we often are selling stocks that we still believe offer meaningful upside. However, if that investment is no longer one of our most compelling, then we redeploy that capital into a stock that is.

LHP: Do you use quantitative methods for portfolio construction?

LA: We have actually developed a very robust quantitative research effort, which I think is unusual for a fundamentally oriented investment firm. All of our investment decisions are primarily driven by fundamental considerations, but our quantitative research effort has helped us in many different ways. In terms of portfolio construction, our quantitative effort plays a critical role in our decisions regarding the sizing of individual positions, factor exposures, and the risk profile of the portfolio.

One of the unexpected benefits of incorporating quantitative approaches into our investment process is that it has both demanded and enabled a disciplined fundamental process that is very thorough and consistent across industry sectors and regions. Most of our quant work is very dependent upon the bottoms-up research and conclusions of our investment team. So we recognized early on that we had to take steps to ensure these fundamental inputs were very reliable, which has really improved our research process—a very nice unintended consequence.

LHP: Why do you think you beat the market, and who takes the other side?

LA: First of all, I think we’re fortunate to have an unusually talented investment team. Our investment team is quite deep but also very experienced as the average investment professional has over a decade of investment or industry experience, the majority of which has been spent at Maverick. So while that ratio of four investments per professional that I previously mentioned is a huge advantage, the talent of each professional, which is obviously harder to quantify, is the more critical factor in our success.

The fact that we are completely indifferent to index weightings gives us a meaningful advantage as well. A significant portion of the capital invested in the markets is invested in a manner that is very aligned with the relevant weightings to an index, typically on a cap-weighted basis. At Maverick, we are blissfully ignorant of a particular stock’s or sector’s weighting in any index—all we care about is the attractiveness of an investment on a risk-return basis.

Last but not least, I think stability has been a big advantage for us over the years. We’ve enjoyed stability of both our investment team and our investor base, which really does allow us to invest with a longer term horizon. The vast majority of the capital we manage is attributable to profits we have generated for our investors, and most of the capital we manage has been invested in Maverick for more than ten years. We’re relatively unconcerned with short-term swings in our performance because we’re confident that our investors share our longer term perspective. Finally, the stability of our portfolio is very helpful; on the long side, our average holding period is over a year. For the hedge fund world, that’s an unusual time frame that allows us to get to know our companies and their management teams quite well. Management teams appreciate investors that act as long-term partners instead of short-term traders.

LHP: So, if certain stocks are out of favor, other investors might recognize it, but they might not want to buy if they think that they need to hold it for a long period to make the profit?

LA: Yes, and, going back to your earlier question about the time frame over which you’re comparing your expectations to those of the rest of the world, I think that many hedge funds are just looking out one or two quarters. By being focused longer term, we are operating in a less competitive landscape. Further, over the long term, fundamentals have to play a bigger role as markets eventually recognize true underlying values, and the shorter term illogical dislocations become less relevant.

LHP: Warren Buffett has said that he likes to hold forever. Would you also go to that extreme?

LA: No. I have a great respect for Warren Buffett and agree with the vast majority of his philosophies. But this is one tenet that I’ve always disagreed with because I believe in our portfolio we have a responsibility to invest our capital as effectively and efficiently as we can day in and day out. If you’re holding a stock forever, by definition there will be periods of time when there are more attractive uses for your capital. The approach of “Too bad—I’m wedded to this stock.” does not allow an investor to free up that capital to redeploy it in a more attractive opportunity. While we may still respect the management team and still believe the company will do well, if we have identified an investment that we believe is more compelling, then we will redeploy our capital.

LHP: What makes a person a good investor, e.g., what do you look for when you hire?

LA: First and foremost is integrity. We’ve now been in business for over twenty years, and over that time we have worked awfully hard to develop a reputation we’re very proud of. If any member of our team were ever to make an unethical decision, all that effort can be unwound overnight. This is a pretty amazing industry in that we can pick up the phone, call a brokerage firm, and invest hundreds of millions of dollars given the broker’s confidence that when we place that order, we will fulfill our obligation. I’m not aware of other businesses that work this way. Likewise, our investors will not entrust their capital with us unless they have complete confidence that we will consistently put their interests first and conduct ourselves in an appropriate manner at all times. I think one of the factors that some firms may overlook when evaluating people is personal integrity because even a junior person can make a decision that can have a dramatic impact on the reputation of your firm.

Number two, dedication. This is a very, very competitive business. There is a significant amount of brainpower chasing similar opportunities. At the end of the day, working more intelligently and working harder tends to have a high correlation to success.

We’re looking for folks who can think creatively and develop a differentiated point of view. Investing is not a skill where you can simply complete a checkpoint process or crank through one particular methodology and automatically come to the correct conclusion. The ability to develop a fresh perspective on an investment thesis or recognize a different angle to evaluate an investment is critical to being a successful investor over time.

People skills play a significant role. It’s important for us to develop strong relationships, not just with the management teams of the companies we invest in, but also with their competitors, suppliers, and customers. Those that have stronger people skills are more likely to be successful in developing those dialogues and more likely to understand when different individuals are not being as forthright as you would hope.

Finally, a very strong competitive streak is crucial. For virtually everyone here, one of the aspects we really enjoy about being in this business is that we recognize that everyone is keeping score. We strive to develop a reputation that we’re proud of and that is driven both by how we conduct ourselves and, of course, by the performance we deliver to our investors.

LHP: Is there a specific trade that has been important to your career?

LA: Our general counsel only allows us to talk about losing trades. So here is a trade that was indeed important to my career, but it’s not something I’m proud of. If you go back to 1994, there were a couple of important software trends in place. One was the adoption of Microsoft Windows 3.1, which was a real breakthrough in terms of the usability of operating systems. Secondly, the first meaningful gaming platform war developed between Sega and Nintendo, which was intensified by the introduction of the Sony PlayStation later that year. We had the belief that both of these developments would spur significant software sales for both PCs and gaming. At the time, there were two retailers that dominated this space, Babbage’s and Software Etc. They were primarily mall-based retailers of software. We thought each may represent interesting investments given these two strong secular trends, and, as we were doing our work trying to understand the dynamics between the two, they decided to merge. The company that they formed was called NeoStar.

This was now a very compelling investment in my mind. In addition to these tremendous tailwinds, there were huge potential synergies in putting these two businesses together in terms of reducing the competitive dynamics in pricing, closing stores that directly competed with one another, and by improving the bargaining positions with their suppliers given their newfound scale. As I look back, I still think it’s fair to say that we were right on all the above.

Unfortunately, despite these tremendous opportunities, the company went bankrupt in less than two years. Why did they go bankrupt? Recall that when you asked me what we look for in potential investment that the top of my list was management. In this case, management ended up getting into a battle of egos between the two sides—not atypical in these situations—regarding who was going to get what responsibility, what title, etc. Management made shockingly poor buying decisions, essentially double-ordering in the chaos of the merger, so the inventory levels ended up being wildly inappropriate. Management did a very poor job of executing on some of the synergies that should have been rather easy to realize. Management leveraged up the balance sheet to a degree that proved unsustainable. I could go on, but you probably get the idea.

So despite getting many of the very important fundamental factors correct, management ended up bankrupting what should have been a great opportunity. Fortunately, we didn’t ride this ship all the way down, but we rode it down far enough still to be a painful memory. The only silver lining is the experience was a very important lesson that there’s so much more to evaluating a stock than just understanding the large secular trends and what looks to be a great opportunity on paper. The ability and decisions of management can trump all other considerations.

LHP: In your core fund, you tend to be a bit more long than short and vary that net exposure over time. How do you think about that timing decision?

LA: To be clear, we have different long–short funds with different levels of gross and net exposure and therefore different risk-return profiles. I believe you’re referring to our flagship fund, in which we typically target net exposure around 45%.

The net exposure does vary, but it’s usually between 30% and 60%. The variation is driven first and foremost by our view of the relative attractiveness of our long and short portfolios. While we do invest a great deal of time to understand macroeconomic factors and consider risks in the market, such perspectives only have a limited influence on our exposures. With that tight range of net exposure, we are unlikely to have a significant impact on our performance through such market-timing decisions. That’s very much on purpose. Timing decisions are very difficult to get right on a sustainable basis. Maverick’s core fund is designed to maintain a balance of longs and shorts within every region in which we invest and within every industry in which we invest, such that macro considerations—whether it be the performance of the markets, sector rotations, etc.—should never have a big influence on our success. Indeed, our success, or lack of success, is driven by our ability to generate alpha through security selection—again, on purpose, because that’s the skill in which we have the greatest confidence in our abilities.

___________________

1 See Novy-Marx (2013) and references therein.

2 This section is based on Frazzini, Kabiller, and Pedersen (2013).

3 See Shefrin and Statman (1985) and Frazzini (2006).

4 See, e.g., Cramer (2002).