Chapter 3

A Never-Ending Torah: The Unfolding of a Tradition

In This Chapter

Discovering the essence of a faith: The Five Books of Moses

Discovering the essence of a faith: The Five Books of Moses

Looking at the Hebrew Bible

Looking at the Hebrew Bible

Uncovering Judaism’s oral tradition: The Talmud

Uncovering Judaism’s oral tradition: The Talmud

Telling stories: The literature of midrash

Telling stories: The literature of midrash

Judaism has survived for almost 4,000 years, including 2,000 years without a homeland, without the Temple in Jerusalem, without any common geographical location, and without support from the outside. Judaism and Jews survived because of Torah. No matter where they lived, no matter what historical horrors or joys they experienced, the heart of their faith was carried and communicated through the way, the path, and the teachings of Torah.

Torah: The Light That Never Dims

The word Torah (“teaching”) refers to the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, which are written on a scroll and wound around two wooden poles (see Figure 3-1). Hand-lettered on parchment, the text has been carefully copied by scribes for more than 2,500 years. On one level, the five books narrate a story from the creation of the world to the death of Moses, around 1200 BCE On a deeper level, the Torah is the central text that guides the Way called Judaism.

Rob Melnychuk/Getty Images

Figure 3-1: Ashkenazi Jews cover the scrolls with a richly decorated cloth.

The five books of Moses

Genesis (Bereisheet, “In the beginning”): Deals with the creation of the world, the patriarchs and matriarchs (including Abraham, Sarah, and Jacob), and concludes with the story of Jacob, Joseph, and the eventual settlement of the Hebrew people in Egypt (see Chapter 11).

Genesis (Bereisheet, “In the beginning”): Deals with the creation of the world, the patriarchs and matriarchs (including Abraham, Sarah, and Jacob), and concludes with the story of Jacob, Joseph, and the eventual settlement of the Hebrew people in Egypt (see Chapter 11).

Exodus (Sh’mot, “Names”): Tells of the struggle to leave Egypt, the revelation of Torah on Mount Sinai (including the Ten Commandments), and the beginning of the journey in the wilderness.

Exodus (Sh’mot, “Names”): Tells of the struggle to leave Egypt, the revelation of Torah on Mount Sinai (including the Ten Commandments), and the beginning of the journey in the wilderness.

Leviticus (Vayikra, “And He called”): Largely deals with levitical, or priestly, matters concerning the running of the Sanctuary, although this book includes some incredible ethical teachings, as well.

Leviticus (Vayikra, “And He called”): Largely deals with levitical, or priestly, matters concerning the running of the Sanctuary, although this book includes some incredible ethical teachings, as well.

Numbers (BaMidbar, “In the wilderness”): Begins with taking a census of the tribes and continues with the people’s journey through the wilderness.

Numbers (BaMidbar, “In the wilderness”): Begins with taking a census of the tribes and continues with the people’s journey through the wilderness.

Deuteronomy (D’varim, “Words”): Consists of speeches by Moses recapitulating the entire journey. Deuteronomy concludes with the death of Moses and the people’s entrance into the Promised Land.

Deuteronomy (D’varim, “Words”): Consists of speeches by Moses recapitulating the entire journey. Deuteronomy concludes with the death of Moses and the people’s entrance into the Promised Land.

When these five books are printed in book form (rather than on the scroll), they’re usually called the Chumash (from chamesh, “five”; remember that this “ch” is that guttural “kh” sound), or the Pentateuch (this is Greek for “five pieces” and not Hebrew, so here the “ch” is a “k” sound, like “touk”). Because tradition teaches that Moses wrote the books based on Divine revelation, basically taking dictation from God, the books are also called the Five Books of Moses.

If you had your latté this morning, you may have noticed that the Torah is said to have been dictated to Moses, even though it includes the story of his own death and burial. Traditional Jews (see Chapter 1) don’t have any problem with this contradiction because to a traditional Jew, the words are those of God, not Moses.

The weekly readings

The Sefer Torah (Torah book, or scroll) is the most important item in a synagogue, and it “lives” in the Aron Kodesh (the “Holy Ark” or cabinet, which is sometimes covered with fancy curtains and decorations). A portion of the Torah is read in every traditional synagogue each week, on Mondays, Thursdays, Shabbat (see Chapter 18), and on holidays (see Figure 3-2).

The five books are divided into 54 portions called parshiot (each one is a parashah), also called sidrot (each one is a sidra). At least one parashah is read each week of the year; some weeks have two parshiot to make it fit the Jewish year correctly. Some synagogues divide the Torah portions differently so that it takes three years, instead of one, to read all five books.

During a synagogue service on Shabbat morning, the Torah reading is followed by the Haftarah (see the section later in this chapter). Traditionally, the person who reads the Haftarah also repeats the concluding verses of the parashah called the maftir.

Eric Delmar/Getty Images

Figure 3-2: The Torah scroll is always read with a pointer so that fingers won’t touch the type.

The TaNaKH: The Hebrew Bible

The five books of the Torah appear as the first of three sections of the Hebrew Bible, which contains 39 books reflecting texts that were gathered over almost 2,000 years. Another name for the Hebrew Bible is the Tanakh, which is actually an acronym made up of the first letters of the names of each of the three sections: “T” is for Torah, “N” is for Nevi’im (“Prophets”), and “KH” is for Ketuvim (“Writings”).

Nevi’im (“Prophets”)

Nevi’im (neh-vee-eem) contains a record of most of the important history for the roughly 700 years after Moses (see Chapters 12 and 13). The history is told in the Books of Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings. Nevi’im also includes the words of the great sixth-century BCE prophets like Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Ezekiel. The last 12 books in Nevi’im — from Hosea to Malachi — are much shorter, and they’re often grouped together as “The 12 Prophets.”

Ketuvim (“Writings”)

Ketuvim (keh-too-veem) is a collection of books, but the books don’t necessarily relate to one another. Some (Ezra, Nehemiah, and Chronicles) relate history; some (like Proverbs) relate, well, proverbs. The Books of Ecclesiastes and Lamentations express some of the bleaker reflections on life.

The Book of Psalms, the longest book of the Bible, contains 150 poems of praise, yearning, and celebration that form the basis of many prayers and hymns both in Jewish and Christian traditions. The Books of Job, Ruth, Esther, and Daniel record epic moral and religious quests. The Song of Songs is a beautiful love poem that many people read as a metaphor for the relationship between God and the Jewish people.

After being passed down orally for centuries, most of the individual books of the Tanakh were written down by the third century BCE. However, Jewish scholars didn’t determine the official canon — the list of books that “made it” into the Bible — until 90 CE, in the city of Yavneh (also called Jamnia). The scholars of Yavneh left out several books that came to be included in the Septuagint (the Greek translation of the Bible), including the Apocrypha (“hidden books”), like the four books of Maccabees. However, Roman Catholic and Greek Orthodox Bibles include these books because they’re based on the Septuagint.

The Haftarah

Each of the 54 parshiot is associated with a section from Nevi’im (historical and prophetic books of the Hebrew Bible). Those 54 sections of the Nevi-im are called Haftarah (the name “Haftarah” means “taking leave,” representing an additional reading following the Torah portion). Most historians think that during a particularly repressive period, perhaps as early as the second century BCE when public reading of the Torah became a capital offense, scholars instead read non-Torah texts that would remind them either by theme or characters of the weekly Torah portion. In this way, people could remember what Torah portion should have been read. Later, when the ban was lifted, this extra reading was retained, so even today, Jews typically read both the Torah and the Haftarah texts on Shabbat and festivals.

Interpreting the Bible

Jewish “fundamentalism” doesn’t focus on the “literal truth” of the Bible like some other forms of religious fundamentalism do. Although many traditional Jews believe that the Tanakh expresses the Word of God, very few Jews would argue that the literal meaning of the words is the right one. An important rabbinic teaching says that there are 70 interpretations for every word in Torah — and they’re all correct! Jewish tradition talks of four dimensions of meaning: the literal, the allegorical, the metaphorical, and the mystical.

Studying different interpretations is called hermeneutics, and it’s an important part of the Jewish understanding of Torah. Hermeneutics is why five different rabbis can make five different sermons on the same text. More fundamentalist Jewish groups don’t focus on an exclusive interpretation of the Torah text as much as on a very strict application of ritual practice.

A Hidden Revolution: The Oral Torah

The written Torah may be the central text of the Jewish people, but if that’s all we Jews had, we’d be in trouble. For example, the Torah doesn’t explain how to perform a religious marriage, what “an eye for an eye” really means, or even how to honor Shabbat and the other holidays (especially ever since the Temple was destroyed and Jews could no longer make animal sacrifices). Think of the Torah as the musical score to an amazing symphony; the written music contains the notes but doesn’t say how to play them. Jews need more than the Torah scrolls to know how to “play” Judaism.

The “musical direction” is provided by the “Oral Torah,” a set of teachings, interpretations, and insights that complement the written Torah. One of Ted’s professors in seminary, Dr. Ellis Rivkin, spoke of the development of Oral Torah as one of the most profound religious revolutions of all time. Without it, he taught, Judaism could hardly have survived for as long as it has.

Traditional, Orthodox Jews believe that Moses not only received what became the Written Torah (Torah sheh-bikh-tav) at Sinai, but also the Oral Torah (Torah sheh-b’al peh). The oral tradition itself states: “Moses received the [Written and Oral] Torah from Sinai and handed it down to Joshua, and Joshua to the elders, the elders to the prophets, and the prophets handed it down to the men of the Great Assembly . . .” So Jews not only see the Written Torah as the word of God, but the Oral Torah, as well.

This oral tradition would, centuries later, itself be written down in the form of the Mishnah, the Talmud, and the midrash — only to be further interpreted by countless more rabbis and students, developing into the Judaism of today. Each time the oral tradition is written, it gives rise to the next step of the process.

The law of the land: The Mishnah

The early scholars and teachers (roughly between 100 BCE and 100 CE) developed guidelines for a continuing Way of Life, called halakhah. Whether or not halakhah (which is usually translated “legal material” or “law,” but literally means “the walk” — as in “walking the talk”) was originally divinely given, it provided the structure for the community’s practice of Judaism. For more than two hundred years this body of material developed orally, and because it was considered an oral tradition, Jews were prohibited from writing it down.

However, after hundreds of thousands of Jews were killed by the Romans in the early years of the first millennia (see Chapter 14), and halakhah continued to become more complex, Jews realized the importance of codifying the expanding traditions in writing. Although some of the earlier rabbis had collected material before him, Judah Ha-Nasi (“Judah the Prince,” who is also simply called “Rabbi”) finally codified the laws, creating the Mishnah between 200 and 220 CE.

The Mishnah (the name derives from “a teaching that is repeated,” indicating its origin as an oral tradition) includes lessons and quotations by sages from Hillel and Shammai (first-century rabbis) through Judah Ha-Nasi (who lived in the third century). The Mishnah contains a collection of legal rulings and practices upon which Jewish tradition still depends. The Mishnah is organized like a law book (as opposed to the narrative of the Torah), splitting up the Jewish Way into six basic sedarim (“orders”):

Zera-im (“Seeds”): Blessings and prayers, agricultural laws

Zera-im (“Seeds”): Blessings and prayers, agricultural laws

Mo-ed (“Set Feasts”): Laws of Sabbath and the holidays

Mo-ed (“Set Feasts”): Laws of Sabbath and the holidays

Nashim (“Women”): Marriage, divorce, and other vows

Nashim (“Women”): Marriage, divorce, and other vows

Nezikin (“Damages”): Civil laws, idolatry, and Pirke Avot (“Ethics of the Fathers,” which is a collection of ethical quotes and proverbs by the rabbis)

Nezikin (“Damages”): Civil laws, idolatry, and Pirke Avot (“Ethics of the Fathers,” which is a collection of ethical quotes and proverbs by the rabbis)

Kodashim (“Hallowed Things”): Temple sacrifices, ritual slaughter, and dietary laws

Kodashim (“Hallowed Things”): Temple sacrifices, ritual slaughter, and dietary laws

Tohorot (“Purities”): Ritual cleanliness and uncleanliness

Tohorot (“Purities”): Ritual cleanliness and uncleanliness

The teachings explained: The Talmud

The ancient sages feared that once the Mishnah was written down it wouldn’t meet the demands of changing times, and they were right. Academies of Jewish learning grew in Palestine and Babylonia (modern Iraq) to discuss new issues raised by their consideration of the Mishnah. Most of the rabbis had other jobs, but their true love was meeting in the academies to discuss, argue, and debate concerns arising from the text of the Mishnah, new legal issues, the Torah, stories of supernatural events, and a host of other matters.

Their dialogues were the beginning of another part of the Oral Torah, the Gemara (“completion”). The Gemara is basically a commentary on the various teachings of the Mishnah. Where the Mishnah dealt mainly with matters of halakhah, the Gemara contained both halakhah and aggadah (“discourse,” stories, legends, and pieces of sermons; the tales and the teachings that “read between the lines” of Tanakh and Talmud). The Mishnah with the Gemara became known as the Talmud (“teaching”).

In size, the Tanakh is dwarfed by the massive Talmud, which often appears in as many as 30 volumes (with translations and commentary). Note that most traditional Jews don’t focus on “Bible study”; they focus on the study of the Talmud. However, the Bible does tend to be the focus for more liberal Jews.

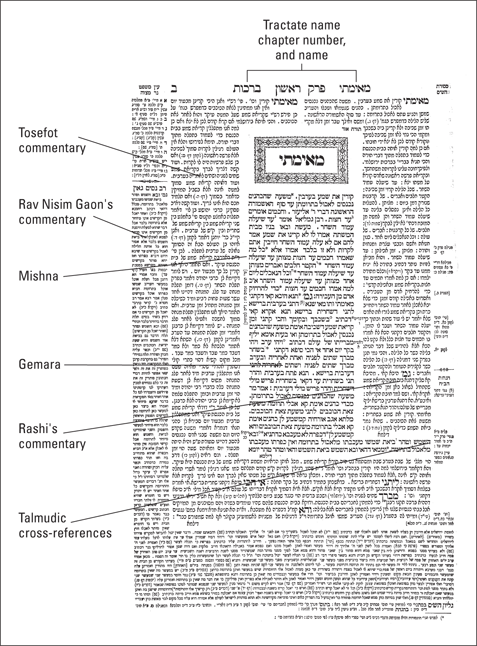

Reading the Bible is hard, especially without helpful commentary, but reading the Talmud is orders of magnitude more difficult (take a look at Figure 3-3 to see how much information is crammed on to just one page). Discussions frequently contain several radically different opinions, offered by rabbis who appear to be in the same room but actually lived in different centuries. The arguments often appear nonlinear, like a free-association or like surfing on a cosmic Internet. Some people say that you don’t read the Talmud, you swim in it. But behind the complexities of the text, the Talmudic scholars find profound insights and deep meaning.

Figure 3-3: A sample page from the Talmud.

So, with the completion of the Talmud, was the oral tradition finished? Of course not. Commentaries, codifications, questions, and answers continue to unfold through books, articles, and rabbinic discussions. This ongoing, unending discussion is also considered part of the Oral Torah.

Telling stories: The midrash

Perhaps the most fascinating parts of Oral Torah (at least to lay readers) is the large body of midrash (from d’rash, an “exposition,” or “sermon”) that contains both halakhic and aggadic materials. Most people focus on the aggadah — those tales and the teachings that “read between the lines” of Tanakh and Talmud. The most well-known collections of midrash span the years between the fourth and sixth centuries, although the midrashic form continued in collections through the 13th century, and midrash even exists today in the form of contemporary sermons, stories, and homilies.

It is in midrash that the great creative and imaginative genius of the Jews blossomed, and you often find psychological, emotional, and spiritual insights in it. A kind of play is possible in aggadah that was usually inhibited in Talmudic legal discussions, and tradition has it that God smiles when people write and discuss aggadah.

For example, one famous midrash explains an apparent inconsistency in the Book of Genesis, in which both man and woman are created in the first chapter, but then the man is suddenly alone in the second chapter. A midrash says the first woman was named Lilith, but Adam couldn’t get along with her. He complained bitterly to God: “We can’t agree on anything. She never listens to me!” So, according to that midrash, God banished Lilith and replaced her with Eve, with whom Adam could better relate. A very long time later, the Jewish feminist movement embraced Lilith because she was created equal to Adam. Remember, this is midrash — just a story.

The Expanding Torah

The word Torah has a third and even larger meaning beyond the written and oral law, too. Torah is the Jewish Way. Torah is the whole thing. Torah is 3,800 years and counting. Torah is the expanding, evolving quest of a people exploring the nature of Ultimate Reality and the responsibilities of Human Being.

The five books are commonly named Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy, following the naming in the early Greek translation of the Bible. Ted’s wife, Ruth, learned to remember the names with the mnemonic: “General Electric Lightbulbs Never Dim.” Note that the Hebrew names for the books are very different (they’re taken from the first unique word that appears in each book):

The five books are commonly named Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy, following the naming in the early Greek translation of the Bible. Ted’s wife, Ruth, learned to remember the names with the mnemonic: “General Electric Lightbulbs Never Dim.” Note that the Hebrew names for the books are very different (they’re taken from the first unique word that appears in each book): Chapters and verses in the Hebrew Bible were a much later invention, when the Latin “Vulgate” translation was created (405 CE). Instead, each parashah of the Torah has its own name, like “Parashat Noakh,” which corresponds to Genesis 6:9–11:32.

Chapters and verses in the Hebrew Bible were a much later invention, when the Latin “Vulgate” translation was created (405 CE). Instead, each parashah of the Torah has its own name, like “Parashat Noakh,” which corresponds to Genesis 6:9–11:32. For example: When Abraham hears

For example: When Abraham hears  More liberal Jews tend to discount the transmission of the Oral Torah at Sinai; instead, they believe that the Oral Torah slowly evolved over time. These folks appreciate that pieces of Mishnah, Talmud, and midrash still hold eternal truths, but they also believe that some passages tied to ancient cultural environments are no longer relevant.

More liberal Jews tend to discount the transmission of the Oral Torah at Sinai; instead, they believe that the Oral Torah slowly evolved over time. These folks appreciate that pieces of Mishnah, Talmud, and midrash still hold eternal truths, but they also believe that some passages tied to ancient cultural environments are no longer relevant.