Chapter 11

Let My People Go: From Abraham to Exodus

In This Chapter

The mything truth of the Bible

The mything truth of the Bible

The origin of the Jewish people

The origin of the Jewish people

How to make a fortune by interpreting dreams

How to make a fortune by interpreting dreams

From Egypt to the Promised Land

From Egypt to the Promised Land

Many modern Jews enjoy reading other people’s myths — Native American legends, Hindu fables, Buddhist allegories — they all seem fascinating. Of course, if you ask, “Well, what about the stories of the Jews?” those same Jews may look at you funny and say, “You mean the Bible? Oh, that stuff is so tired!” (Or “passé” or “limp” or whatever the current slang is.) However, the nearly 4,000-year-old story of the Jews is anything but tired. In fact, if you look closely enough, you’ll find that Jewish history is just as wild as anything else you might find — it’s filled with mystery, sexual exploits, psychedelic imagery, and even car chases (well, chariot chases).

You can’t tell the story of human civilization — in the East or the West — without exploring the history of the Jews. That’s pretty strange if you think about it, because the Jews have never embodied any more than a tiny percentage of the population on any continent.

In this chapter, we dive in to the oldest part of Jewish history: the myths and legends so old that their only recorded evidence appears in the Bible. The earliest history of the Jews is told in the biblical books of Genesis and Exodus (called Bereshit and Sh’mot in Hebrew). The story lays out a series of beginnings: the beginning of civilization, the beginning of a monotheistic faith tradition, the beginning of codified law, and the beginning of the Jewish people. In fact, the word “genesis” means the origin or the roots, and by looking at the roots of Judaism, you can find out a lot about who Jews are today.

These “creation myths” have been told and retold by Jews for at least 2,600 years (probably much longer), by Christians for some 2,000 years, and by Muslims for well over a millennium. Each event recounted holds deeper meaning: Sometimes it’s a foreshadowing of events to come, sometimes it’s a lesson to apply to daily life. While many Jews take the stories of the Bible as actual history, many more read them as myths — fictional tales carrying deep and timeless truths. The mythic dimension of these stories yields new meanings both personal and communal in every generation that reads them.

The Genesis of a People

The shadowy origins of human beings first take form in the early chapters of Genesis, soon after the world is created. Hard-core traditionalists place this event around 3800 BCE. Curiously, this is just about the time that civilization first sprang up in Mesopotamia (in the area of present-day Iraq). Perhaps Adam and Eve weren’t the first humans, but rather symbolic representations of the first civilized man and woman. Some say the Garden of Eden was watered by the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, which encompass that land and can still be visited today (with the proper visas, of course).

Beginnings of a Way

Of course, the Hebrews weren’t around back then to keep Adam and Eve company. The story of the Hebrews unfolds later in Genesis and Exodus almost like a soap opera, telling the trials and tribulations of one family over many generations.

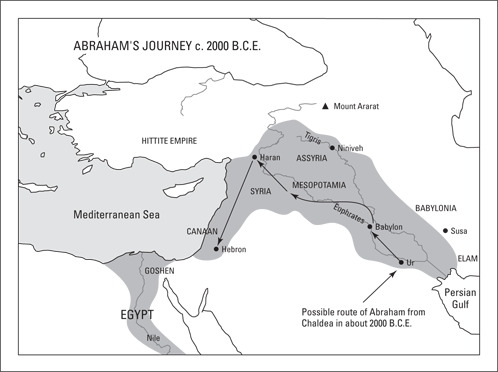

The story starts with a guy named Abram (or Avram, in Hebrew), who, around 1800 BCE, lives in a city called Ur with his wife, Sarai, and his father, Terah. Then, after some years, they all move to a town called Haran (see Figure 11-1).

Figure 11-1: Abraham’s journey from Ur to Canaan begins the Jewish story.

Most people of that era believe in many gods, not just one; they worship gods of cities, gods of mountains, and so on. Abram, however, believes in a single God, who speaks to him, telling him to take Sarai south to the land of Canaan (which is today called Israel). God tells Abram and Sarai that their family will become a great nation and a blessing for all humankind, which is no small promise, given that Sarai can’t have children, and Abram is 75 years old.

This one step — agreeing to follow the voice of his One God and travel to Canaan — establishes Abram as the patriarch of monotheism and the originator of the clan that was to become the Jewish People. On a more symbolic level, Abram leaves everything that is familiar to him and trusts something deeper. He lets go of his old way of life in order to see the Land, a new way of doing things.

After traveling to Canaan, God gives Abram and Sarai new names: Abraham and Sarah. Names in Judaism are linked with identity; the change in their names reflects a change in who they are, and “Abraham” in Hebrew means “father of a multitude.” “Sarah” means “princess,” or a woman of high rank.

The next generation

Sarah is frustrated that she can’t have children (they are both in their 80s); she suggests that Abraham sleep with her Egyptian maidservant, Hagar. This works for Abraham, and soon after, Hagar gives birth to a son, Ishmael. God blesses Ishmael, and both Jewish and Islamic traditions hold that Ishmael later becomes the father of the Arab tribes (thus making Jews and Arabs cousins).

Finally, when Abraham is 99 years old, God comes once again to make a deal: God will grant him a child with Sarah, and the child will be the ancestor of a great nation — but first Abraham must seal a covenant with God by circumcising himself, his male servants, his 13-year old son Ishmael, and agree that all his male descendants must be circumcised. The choice couldn’t have been an easy one, but Abraham agrees, and Sarah soon after conceives, giving birth to a son, whom they circumcise and name Isaac. (“Isaac” stems from the word “laughter.”)

Problems have been brewing for years between Sarah and Hagar, and now Sarah insists that Abraham send Hagar and Ishmael away, a task he doesn’t relish. But God tells him to do what Sarah says, so he sends them off.

Now the Bible launches into a baffling story in which God seems to test Abraham’s faith. Abraham hears God calling to him, “Abraham,” and Abraham responds “Hineini” (“Here I am.”) Then, God tells Abraham to sacrifice his beloved son Isaac.

Can you imagine choosing to do this to your own son, especially one for whom you’ve waited a hundred years? This is a powerful and complex story of faith, and one that Jews reread and re-examine each year at Rosh Hashanah (see Chapter 19). However, remember that every story in Genesis is a teaching story, and this hair-raising tale is an important aspect of the commitments of the Jewish people.

Abraham takes Isaac to Mount Moriah (the future site of the great Temples, in the center of modern-day Jerusalem) and binds him for the sacrifice. (That’s why this story is commonly known as the Akeda or “the binding.”) However, just as he raises his knife, Abraham hears an angel say, “Do not hurt the boy . . . Now I know that you truly fear God, for you have not withheld even your son from God.” Abraham releases Isaac and instead sacrifices a ram that he finds caught in a nearby thicket.

The Akeda story illustrates the prohibition against child-sacrifice, which had been a part of previous cultures in that area. Jews also believe that it speaks to a deep question of healthy and unhealthy ways in which to demonstrate faith.

Who gets blessed?

Isaac, too, is considered one of the great patriarchs of Judaism, but the Bible doesn’t say he did much other than marry Rebecca, grow to be prosperous, and father two boys: Esau and Jacob (more on them in a moment).

Jacob and Esau are twins, and they fight incessantly even while in Rebecca’s womb. Esau is born first, and Jacob follows, clutching Esau’s heel, a sign that he would be a “usurper.” (The Hebrew name for Jacob stems from the Hebrew word “heel” and has the sense of “one who seizes the power of another.”) The two boys represent the conflict between the hunter Esau and the gentle man (who later becomes the prototype for the scholar) Jacob.

Isaac clearly favors Esau’s virile strength over the more gentle and quiet energies of Jacob. However, when Isaac grows old and blind and it comes time for him to bless Esau with his birthright, Rebecca tricks him into giving the blessing to Jacob instead. (In case you need to try this at home, she dresses Jacob in goat skins so that he smells like and feels as hairy as Esau.) Esau returns from the hunt, is understandably upset, and vows to kill Jacob as soon as his father dies.

Jacob takes the hint and gets out of town. Fast. But on his sojourn, he begins to mature into his own spiritual wholeness. The first night out, he dreams of a ladder that connects heaven and earth. He experiences himself accompanied by the Divine Presence, watching angels ascending and descending that ladder. He awakens with newfound awareness: “Surely the Eternal is in this place, and I did not know it”

He begins walking his own path and goes to live with his mother’s brother Laban (or Lavan) in Haran. There, he falls in love with Laban’s daughter Rachel and agrees to work for Laban for seven years in order to marry her. Seven years pass, and Jacob and Rachel marry. But the next morning Jacob finds out that he actually married and slept with Rachel’s sister Leah. (What, did she wear a veil the whole night?) Laban confesses to the trick, but says that Jacob will have to work another seven years to get Rachel, too. (Remember that it wasn’t uncommon at the time — around 1650 BCE — to have more than one wife.)

Wrestling with God

While Jacob lives and works in Haran, he and Leah have seven kids: Reuben, Simeon, Levi, Judah, Issachar, Zebulun, and Dinah (his only daughter). He also fathers four sons — Gad, Asher, Dan, and Naphtali — with Leah and Rachel’s maidservants. And finally, he and Rachel have a son: Joseph. (Jacob and Rachel later have one more son, Benjamin; sadly, she dies while birthing him.) So by the time Jacob is ready to return to Canaan, he’s got quite a lot of family and resources.

On the way south to Canaan, Jacob decides to spend the last night alone before his reunion with his estranged twin, Esau, so he sends everyone else ahead. In a very sparse biblical narrative, “a man” comes and wrestles with Jacob all that night. When daylight is about to break, the man asks Jacob to let go of him. Even though Jacob is wounded in his thigh, he doesn’t release him, and says, “I will not release you until you bless me.”

Jewish tradition holds that the “man” was, in fact, an angel of God. The angel’s blessing comes in the form of a significant change of name: The angel says, “Your name is no longer Jacob, but rather Israel (Yisrael), for you have contended with God and with men and you have prevailed.” Of course, this makes no sense whatsoever unless you know that the name Yisrael can mean “one who wrestles with God” (some translate it “one who persists for God,” or “prince of God”).

Jacob’s descendants, then, become the “children of Israel,” and every one of Jacob’s sons (except Joseph and Levi) later grows up to become the leader of a major tribe: the Tribes of Israel. Joseph’s two sons grow up to lead their own tribes, and the Levites become teachers and priests for the other tribes.

The Son Also Rises

Many tales help define the people who will later become the Jews, and they all begin with the story of Joseph. Because of Jacob’s deep love for Rachel, the woman for whom he served Laban so many years, her firstborn son Joseph was clearly his favorite child. Joseph’s brothers, not surprisingly, were jealous, and as Joseph grew older, he seemed to play into that jealousy rather than try to downplay it.

Joseph seems to be an obnoxious sibling. He rats out his older brothers when they do less-than-honorable acts, and he tells everyone about his dreams in which, symbolically, his brothers, and even his parents, bow down to him. His brothers finally plot against him, and, when they have the chance, capture him and fling him into a pit. However, instead of killing him, they sell him as a slave to a group of traveling traders and return home with his famous many-colored coat (the symbol of his special status with his father) soaked in the blood of a goat. Jacob believes that Joseph has been killed by a wild animal and grieves for his lost son.

Meanwhile, Joseph begins an unexpected journey to greatness. He’s nothing if not resourceful, and instead of meeting the fate common to slaves at the time (an early death from overwork), Joseph proves himself to be a master manager. After he’s brought to Egypt, he ends up in the home of Potiphar, an influential member of the Pharaoh’s court, and Joseph is soon given authority over the entire household.

Joseph happens to be very handsome, and he attracts the interest of Potiphar’s wife, who makes more than one pass at him. When Joseph continually refuses her advances, she finally becomes enraged, grabs his shirt as evidence, and screams that he has molested her against her wishes. Joseph is thrown into the dungeon. But even then he doesn’t bemoan his fate. Instead, he demonstrates such managerial skills and competence that he is soon running the dungeon.

Interpreting dreams

Dreams hold a special place in the Bible, providing deeper insight into the events of this early, mostly mythical, history. As a child, Joseph’s dreams of grandeur got him in trouble with his siblings, but sitting in prison, he finds that, with God’s help, he can interpret the dreams of two other inmates, a cupbearer and a baker. He says that their dreams mean that in three days the cupbearer will be released and the baker will be executed — both of which come true. Two years later, the Pharaoh himself has a series of dreams that no one else in the kingdom can interpret. The cupbearer remembers Joseph and recommends him to the Pharaoh, who has him brought up from the dungeon.

The Pharaoh dreamt that seven lean cows consumed seven fat cows, and then that seven withered ears of grain swallowed seven full and ripe ears of grain. Acknowledging God’s help, Joseph explains that following seven years of abundance, there will be a seven-year famine in the land of Egypt. He then encourages the Pharaoh to plan for the bad years by storing food during the years of plenty. He further indicates that this planning will enable Egypt to gain power during the bad years, since people from near and far will come to Egypt for food. He also suggests that the Pharaoh appoint someone to organize and manage such an enterprise, and the Pharaoh (of course) chooses Joseph, making him second-in-command over all Egypt.

A dream comes true

Everything Joseph predicts comes to pass, and after seven years of bounty, during which Joseph organizes the storage of produce, the land is struck with a terrible drought. The people of Egypt and the outlying areas trade their riches and their lands to the Pharaoh (through Joseph) for food. Before long, Joseph’s brothers arrive from Canaan, sent by Jacob to buy grain. They don’t recognize Joseph, but Joseph certainly recognizes them, and as they bow before him, his childhood dreams come true. However, time has changed Joseph from a spoiled brat to a real mensch (a stand-up guy; see Appendix A for details), and instead of treating his brothers poorly, he acts compassionately.

Joseph tests his brothers’ integrity, and finds that they, too, have changed over the years. Of course, when he finally reveals his identity to them, they’re terrified that he will seek retribution. But Joseph reassures them, saying it wasn’t them who had sold him to slavery, but God, and that God had clearly meant for all this to happen so that he would be able to provide food for his family. (This is one of our favorite passages in the Bible, and especially helpful to remember when everything seems to be going wrong.)

In the final scene of this act, the Pharaoh tells Joseph to bring his family to Egypt and gives them the fertile area called Goshen (which was probably in the Nile delta area) as their home. Coming from a place stricken by famine, Egypt must have seemed like a real promised land for Jacob and his family. And perhaps it was for a time. But then things changed.

The Enslavement and Exodus

Beginning with the book of Exodus, the Bible shifts from telling stories of a family to telling stories of a people. The Children of Israel thrived while in Egypt, but after a couple centuries, “A king arose in Egypt who did not know of Joseph,” and because he feared the Hebrews, he enslaved them.

Although archeologists haven’t found any direct archeological evidence of the enslavement of the Hebrews, historians can point to an overlap between the Bible and known history. For example, early records tell of a people, called Apiru or Hapiru, who appeared in Egypt in the fifteenth century BCE. The word “Hapiru” may be the origin of the word “Hebrew,” although it seems to have indicated a social class rather than a particular clan or family; some scholars note that the word “Hapiru” may have meant “refugee” or “someone on the fringe of society” in the ancient Canaanite language.

Historians have documented cases of non-Egyptian courtiers (perhaps like Joseph) who rose to significant power in the eighteenth and nineteenth Egyptian dynasties. However, when the Pharaoh Ramses II took the throne (around 1290 BCE), he began a series of massive building projects, and he probably enslaved a number of groups in Egypt, including perhaps the early tribes of Israel. This matches the Biblical description, which says the Children of Israel were enslaved and forced to build cities called Pithom and Ramses. Note that, contrary to common belief, the Hebrews didn’t build the pyramids. The pyramids were seen as holy sites for the Egyptians that could not be constructed by a slave class.

A star is born

The real birth of the people Israel takes place during their exodus from enslavement in Egypt and their travels back to Canaan. Leading them out of Egypt is the one man who will hold more influence over the Jews than any other: Moses.

The Bible says that Moses was born after the Pharaoh has decreed that all male Hebrew newborns should be killed; so to save his life, his mother places him in a basket in the river, where he is discovered and rescued by a daughter of the Pharaoh. In this way, Moses is actually raised in the Pharaoh’s home as a prince of Egypt.

Moses grows up, kills an Egyptian who was beating a Hebrew slave, flees to the land of Midian, attaches himself to Jethro, a priest of Midian, marries Jethro’s daughter, and has kids. Perhaps while living with Jethro Moses undergoes his own spiritual training, and one day, out by himself with the flock, he sees a burning bush and hears his call from God. Like Abraham before him, Moses knew what to say: Hineini! (“Here I am!”).

God charges Moses with leading the Hebrews out of slavery, and although Moses argues and kvetches, he returns to Egypt to carry out his duty. The experience of God’s Presence is enough to influence Moses to take on an incredibly demanding career.

Finally, after confronting the Pharaoh repeatedly and announcing a series of plagues involving locusts, boils, and finally the killing of the first-born of Egypt, Moses finally gets the Pharaoh to release the Hebrews. As they flee, they approach a body of water that the Bible calls Yam Suf, the “Sea of Reeds.” Yam Suf is usually translated as “the Red Sea,” but it clearly isn’t the same as the body of water known today by that name.

Extraordinary miracles happen throughout the Bible, but this is major: The Bible says that the water of the Sea of Reeds separates so that Moses and the people can cross, but then closes up again over the pursuing chariots of the Pharaoh. For those of you who like more rational explanations, some scholars say that the “sea of reeds” was marsh-like in places, so that the people could walk through it, but the heavy chariots were trapped by the muddy bottom. Whether you accept the miraculous image of the Biblical account or a more mundane possibility, the Hebrews made the crossing safely, and the Egyptians gave up pursuit at that point.

Are we there yet?

The Bible says that 600,000 men over the age of 20 and their families left Egypt. The ancient rabbis figured that the total community, including women and children, could have been 3 million. What a camp out that must have been! Once again, some historians disagree, observing that there probably weren’t that many people in all of Egypt. What’s more, later rabbinic commentators suggest that not all of the Hebrews were willing to leave Egypt. Rashi, one of the most famous rabbinic commentators (see Chapter 28), suggests that only 20 percent of the total Hebrew population left, reflecting how difficult it is to leave known places and strike out for something new.

No matter how many were actually there, the trip from Egypt to Canaan wasn’t a simple one for the Hebrews, and it turned out to be a good deal longer than anyone may have imagined. After the experience at the Reed Sea, Moses led the people to Mount Sinai, in the southern part of the Sinai Peninsula. There, the Bible tells how the people beheld the Presence of God and received God’s instructions to them — what people call the Ten Commandments. At this time they were officially consecrated to God’s service as a holy people.

The Bible itself allows that the journey to Canaan might have only been an 11-day trip, but because the people lost faith that God would enable them to overcome the Canaanite tribes, the journey stretches to 40 years. Historically, this statistic isn’t as outrageous as it sounds. The Hebrews likely chose a route that avoided the most fortified areas, including the Egyptian outposts along the Mediterranean coast and the kingdoms of Edom and Moab (which were in the area we now know as Jordan). Instead, they traveled far east, conquering the Amorite kingdom, and then approached Canaan (and the city of Jericho) from east of the Jordan river.

Moses died at this point, and leadership was given over to Joshua through the first act of s’micha, the laying on of hands, which even today is used to convey the ordination of rabbis and special blessing. The Bible states that no one knows where Moses is buried, perhaps to inhibit any kind of worship that such a place might draw.

Ultimately, everyone in the generation of the exodus, except Joshua and Caleb, would die in the desert before entering the Promised Land.

Entering the Promised Land

Traditional Jews today insist that God gave a large patch of land to the Israelites just before Moses died, an area that actually reaches far beyond current-day Israel. More liberal interpreters of the scripture point out that the Israelites were simply one more conquering nation in a land that had already been conquered numerous times in history.

The Bible has two versions of what happened when the tribes entered Canaan. In one story, they conquered Jericho, and then in three triumphant military campaigns took the whole land, dividing it among the 12 tribes of Israel. In another place, the Bible indicates that the battles weren’t quite so neatly accomplished, and that there was considerable disarray among the tribes.

Whatever the case, for the next 2 centuries — from the end of the 13th to the end of the 11th century BCE — the Israelites lived in Canaan as separate tribes. During these times, they had no central government, and the tribes operated relatively independently unless they were threatened. They were linked by a covenant with a God they shared, and they all cherished the Ark of the Covenant, a shrine located in Shiloh, in the central hill country. In time, the Israelites changed from being a seminomadic people to an agricultural people, building cities and farming the land.

But the seeds of future conflict were already planted. Groups of Canaanites remained in the area. Archeologists have a wealth of evidence showing that the coastal areas were controlled by groups such as the Philistines (who were known as the “Sea People”). By around 1050 BCE, the Philistines — for whom the land “Palestine” was much later named by the Romans — had become powerful enough to defeat the Israelites at Aphek, destroying Shiloh and capturing the Ark of the Covenant. The defeat prompted the Israelites to create their own monarchy in order to more effectively defend themselves against such enemies.

Memorizing an endless series of historical dates and events isn’t the important thing; instead, strive to understand how those beginnings unfolded to place you (yes, you) where you are right now.

Memorizing an endless series of historical dates and events isn’t the important thing; instead, strive to understand how those beginnings unfolded to place you (yes, you) where you are right now. After this episode Jacob is sometimes called “Israel” and sometimes “Jacob.” Perhaps “Israel” reflects a deeper spiritual identity, and “Jacob” (“the usurper”), the everyday self. This patriarch, just like all humans, sometimes remembers and sometimes forgets his deeper self.

After this episode Jacob is sometimes called “Israel” and sometimes “Jacob.” Perhaps “Israel” reflects a deeper spiritual identity, and “Jacob” (“the usurper”), the everyday self. This patriarch, just like all humans, sometimes remembers and sometimes forgets his deeper self.