A MEMOIR AWARDED THE DELL’ACQUA PRIZE IN 1858

Lhe dava a verde folha da herva ardente

Que a seu costume estava ruminando.

(Camoëns, Canto vii, l. 58.)1

Man, in his use and abuse of life, feels the continual need to repair through nourishment his molecular wear and the expenditure of forces that constitute his mode of being. Some of the substances which he takes from the outer world help him to repair in particular the tissues that regularly fray apart in the exercise of their vital actions, and they are called plastic nutrients; while others, made for calorification, are burned by the oxygen breathed into the vast web of all the organs, or are deposited in the form of adipose in cellular tissue, where they serve as spare fuel, and they are given the name respiratory nutrients. To these two classes of nutritive substances, established some time ago by the illustrious Liebig,2 I should like to add a third, namely the nervine nutrients, whose purpose is to heighten the action of the nervous system in all its various attributes.

Needless to say, we should not take this classification of foods very strictly; as ever, it is impossible to do so in the area of physiology and pathology. For here the elements, the phenomena, the functions cross and overlap so frequently and so intricately that it becomes all but impossible to separate even two things without mishandling or destroying them. The analyst’s scalpel, however skillfully and penetratingly it moves over the fabric of life, cannot help but leave some droplet of blood as proof that what was cut into formed a whole. Life cannot be understood in its truth except by considering it in its entirety and in infinitely small moments; whereas studying a single phenomenon across time, although it may be highly useful work and, alas, all too necessary for weak human nature, distracts from the truth and at every step creates artificial distinctions, which we ultimately believe to be facts of nature. For this reason I would like to see banished forever from our science the words for systems, classes, genera, and species, which are at once overambitious and impotent; we should leave them to the exact sciences which, more fortunate than our own, rest upon solid terrain that allows them to draw straight lines with a mathematical hand. We must be content to classify physiological and morbid phenomena, and many others of secondary importance, in families, which bring together the most similar facts without claiming to imprint upon them an indelible mark that would make them recognized by all, infallibly different from other facts: and just as in human families we find closely similar individuals, less similar ones, and seeming interlopers, so it is with our divisions – in which we must never search for a scientific system, but only a thread to guide us through the dark, intricate path of our studies.

All we have said thus far is amply confirmed in the case of foods. No nutritive substance is entirely plastic, respiratory, or nervine. Muscle tissue, no matter how thin, always contains the sugar of flesh, which is a respiratory food; bread contains amylaceous and proteic elements; cocoa, which is a nervine food, contains a material that can aid breathing, and so on. In dividing foods into these three families, we should content ourselves with reuniting them into natural groups that serve to indicate their most important physiological function; and if science has admitted a clear distinction between the plastic and the respiratory, it cannot also refuse to admit the nervine.

These foods are distinguished by the following salient characteristics:

1. They almost invariably act in small quantities, and their action depends more on their nature than their mass.

2. They are consumed only by humans, who possess a more complex nervous life than all other animals. Among these fellow animals, those closest to us in intelligence may like these foods when introduced to them in their domesticated state. Monkeys, parrots, and even dogs often take to coffee and tea; but in their wild state they never instinctively seek out these substances.

3. In the various ages of life their consumption is always proportionate to the cerebral-spinal axis. A baby is content with milk, which to date is not known to contain any nervine nourishment; a child must consume coffee and wine in great moderation and generally feels no need of either. An adult man, at the height of his nerve functions, may consume all nervine foods in careful abundance.

4. A man needs them more than a woman because his brain and his muscles are more active.

5. Civilized man needs and enjoys these foods more than the savage, and in the brilliant deployment of his intelligence may in a single day consume the fermented juices of the vines of Vesuvius, the misty beer of England, the cocoa of America, and the tea of remote China.

6. The stomach, under the immediate action of these foods, creates a peculiar feeling of well-being and rebels against any diet that completely excludes them. Raspail,3 insistently drawing physicians’ attention to the usefulness of fragrant condiments, has rendered a true service to science, once one has pardoned his helminthomania.4 Children and women can feel well for some time on a diet of milk and fruit, but an adult man almost always rebels against it. The sheer drowsiness and dullness of sensation that follow a drink of milk are at the root of this. When milk is heated, this effect is less perceptible, since the heat imparts a stimulating effect that utterly vanishes when wine is added. In this regard, the café au lait dreamed up by a woman of high standing in France is a culinary and hygienic discovery of the first order, for it offers, combined in one pleasant, easily digested form, the three families of foods. The casein represents the plastics, the sugar of the milk and butter supply the respiratory materials, and the coffee stimulates the nerves as one of the principal nervine foods. This drink even contains the salts our skeleton requires. So it is not by mere habit and fashion that some four-fifths of the inhabitants of Europe and America breakfast upon milk mixed with tea, coffee, or chocolate.

7. The nervine foods are almost all absorbed very quickly, and once they enter into the eddy of circulation, at every point in our organism, they stimulate the various regions of the nervous system. Some, indeed, are apparently absorbed without prior digestion, enabling the foods to quickly repair the use of the nerve force. Just as a farmer returning from the field craves nothing so much as a glass of wine, the traveller in South America, after a gallop of fifty miles or more in the pampas, is courteously handed a cup or gourd of mate on the rancho. Once the organism has quickly been strengthened by alcohol or caffeine and by the aromatic properties of mate, the stomach is better disposed to patiently await the more solid, long-lasting restoration of the plastic and respiratory foods.

8. The nervine foods pass unmodified into our organism or undergo further transformations. This is an area in which physiology eagerly awaits fresh illumination from chemistry. Some of these foods, from the wealth of hydrogenic-carbonated properties they contain, have a respiratory value comparable or superior to their nerve power. Such is the case with alcohol and the fat content in cocoa. These foods could be termed nervine-respiratory. Others have a pronounced plastic property, as is the case with tea, which in certain Oriental countries is eaten, and gives the organism a great abundance of casein (neuro-plastic foods).

9. The nervine foods contribute considerably to a happier life. Through their influence, one’s sense of existence is always heightened, moral suffering is mitigated or forgotten, and a cheerfulness is revived that may ascend to the heights of happiness (coca, opium, etc.).

10. These foods exert different influences from one other, adapting to the various needs of life as determined by age, sex, temperament, climate, and race. We can only impatiently await the history of the nervine foods studied in their multiple relations to civilization, health, and medicine. I hope to return to this subject at greater length; for now I must be content to sketch a few lines that may help to show where I would like to situate coca. Suffice it for me to say that these foods find clear-cut favour with given parts of the nervous system. The exertions of the intellect are more quickly repaired by a cup of coffee, whereas alcohols better prepare use of the muscles. Guaranà strengthens the genital organs, whereas opium rekindles the imagination.

11. The words excitement and stimulation should not be understood in the sense given them by the champions of diathesis.5 The nervine foods can serve the life of the nervous system by halting the effects of organic regression and thereby suspending one function for the good of another. To want to expand and elaborate upon this point, however, would be to rush ourselves beyond our current state of ignorance. Let us settle for the little known over the ill-known. […]

The coca, Lamarck’s Erythroxylon6 coca, is a small, prolifically branching tree that reaches a few feet in height and is adorned with alternating, oval, sharp, unary, membranous leaves generally marked by three longitudinal venations, about an inch and a half long and one inch wide. The flowers are small, whitish, grouped over some small tubercules that appear on its branches in May. When the fruit is ripe it is a red, oblong, and prismatic stone fruit.

The coca tree grows only in hot, very humid, and thickly vegetated places called Yungas, along the entire eastern side of the Peruvian and Bolivian Andes. No author, to my knowledge, has yet noted the presence of this cherished little tree in the Argentine Confederation; but I think it can be affirmed upon the authority of a very distinguished American friend of mine, Mr Villafane, the former governor of Oran, who assured me he had seen the coca in the woods of a district in the province of Salta. He confirmed this statement in his most recent work, published last year, and mentioned as well that he knew it to be of the highest quality.

It is hard to trace, in the depths of the historical traditions of America’s indigenous peoples, when the Incas found coca in those virgin forests; when they recognized its precious qualities; and when they brought it to their own fields, which they knew how to cultivate so masterfully with irrigation, tilling, and fertilizing. What is certain is that at the time of the Conquest the Indians of Upper and Lower Peru were considered to have cultivated coca from time immemorial, and to have long reserved it for the royal family and its dependents. There are those who think that the Spanish, by granting free use of coca for all, endeared themselves to the masses tyrannically deprived of one of life’s greatest comforts. At the same time, Pizarro’s companions, by levying heavy taxes on this important commercial item, reaped quite a large harvest for the ever greedy coffers of Spain.7

What seems almost incomprehensible is that the Spanish should never have drawn the attention of learned Europeans to a plant that provided nervine sustenance for an entire nation; and it is even more remarkable that travellers of all nations forgot coca for the span of some three centuries, barely noting it, or else relaying only partial or erroneous information about it. It is also truly notable that in Pereira’s8 great work on medicinal substances I have been able to gather precious little bibliographical information on the subject.

Coca is grown especially in the department of Yungas in Bolivia, where they choose the dampest spots down in the valleys and the first slope of the mountains; there, they build low walls to keep the soil from breaking apart. The coca is sown or planted. In the former case the seeds are deposited in the ground in December and January, the hemisphere’s hottest months, and seedbeds are made, from which the tiny plants are transplanted the following year. This is almost always the preferred method. In any case, the leaves are harvested in the second year.

The harvesting of the leaves, which are the plant’s usable portion, is called mita, and it is repeated two, three, or four times a year. It is done with the greatest diligence, by manually detaching leaf after leaf from branches, and transporting them into various paved courtyards, since the harvesters need them to dry quickly, on stone in the sun. This operation does much to bring out the good qualities of the coca, because if the damp and rainy weather interrupts its drying or wets it, it very easily undergoes a process of fermentation that alters it and changes its effect.

To show the importance of coca in the agriculture of Bolivia, it is enough to note that in several places the coca fields are hedged with coffee plants. To those uninitiated into coca’s pleasures this may seem a true sacrilege, especially when one considers that Yungas coffee is one of the finest in the world.

When the leaves are dried, they form loaves, which are wrapped in banana leaves and covered with a very coarse woollen fabric. Tambor is the name given commercially to the joining of two loaves in one woollen sack; each of these is called a cesto and contains about a rubbo9 of leaves (25 pounds, in pounds of 16 ounces). This very crude way of preserving and shipping coca may suffice for the commerce of Peru and Bolivia, countries with very arid air, but would hardly do for its exportation to distant lands.

Coca is consumed almost exclusively in Bolivia, Peru, and the two Argentine provinces of Salta and Jujuy. I would say that it is also used in the American republics that make up the former state of Colombia, although I have failed to find definite proof of this.

For now, wanting precise data to determine with certainty the annual production of coca in Bolivia, I must content myself with an official, and highly reliable, record published in La Paz in 1832. It states that Bolivia harvests 400,000 cestos of coca annually, 300,000 in the province of Yungas and the rest in those of Larecaja and Apolobamba and the department of Cochabamba. The average price was then 30 francs per cesto in La Paz, the general depository for it, which would bring the Bolivian republic an annual revenue of 12 million francs for its coca production. According to Orbigny,10 Peru, in this same period, produced 1,207,435 francs; in all, 13,207,435, a huge sum given its population. In fact the number of indigenous or mestizo inhabitants of the provinces in which coca is consumed can, in Bolivia, reach roughly 700,000, which would mean an annual consumption of 17.50 francs per person.

However much coca Peru might produce, it always buys a certain quantity from Bolivia, deeming it far superior to its own; and in 1856, 7851 rubbi came from this country, at a value of 205,600 francs. The Argentine republic buys 3,000 rubbi of coca annually from its neigh-bour, a huge quantity given the sparse population of the two provinces, Salta and Jujuy, that consume it, and in which there are rather fewer natives relative to the white population than are found in Bolivia.

Since the official data we have thus far cited were published, the cultivation of coca has spread somewhat, and its price risen. Suffice it to say that it is bought for between 60 and 80 francs, depending on the scarcity or abundance of the harvest, as well as on its quality. In certain years a rubbo fetched even 100 francs. In Salta it is usually sold at 7 francs a pound.

High-quality coca presents whole leaves of medium size and bright green colour. It has a very light fragrance reminiscent of hay or chocolate. It breaks down easily when chewed, and gives off a rather bitter flavour that is not unpleasant.

When steeped in hot water, coca turns an attractive green colour that grows darker the poorer its quality. This tea has a pleasant taste that is like nothing else. The brew has a rather sickening, even nauseating taste.

Coca is always more or less bad when brownish, spotted, or very hard to chew. The worst coca gives off a foul smell, and is close in colour to roasted coffee; it is crushed and reused in a thousand different ways.

The best, from the province of Yungas, may, in certain tiny cestos, fetch a very high price under the name of coca selecta. The worst, since it is very tough and not very powerful, comes from Peru.

Between the worst and the best, then, an infinite variety is to be found, and those varieties can be distinguished only by connoisseurs, who bring to their habit a subtlety of discrimination befitting the voluptuousness of a pleasure studied over many years.

The still uninitiated European pharmacist should always look for the two most salient traits in coca, its green colour and the thinness of its leaves.

Many travellers insist that the fruits of the coca plant serve as coins in Peru, and the Chevalier de Jaucourt,11 who wrote a brief article on this plant in the Grande encyclopédie française, repeats this fact, which I believe to be false. On the other hand he refuses to believe what others have written, namely, that the revenue of Cuzco’s cathedral is but a tenth that of the coca trade.

Other authors have drawn on the coca/cuca distinction to posit two entirely different erythroxylon plants.

I know of no chemical study of this plant and anxiously await Italian research on its active principle. I believe I have been the first in America to prepare a hydro-alcoholic extract, which seemed to me to represent the integral active part of the leaf. This solution was created in the pharmacy of the Flemings, distinguished Irish chemists who settled many years ago in the Argentine Confederation.

Anyone wishing to acquaint himself with coca can find it in the Brera pharmacy run by our illustrious Erba, who does such credit in Italy to pharmaceutical chemistry.12 This is the only coca thus far to be found in Europe.

Coca is consumed in three large regions of South America, namely, Bolivia, Peru, and the Argentine Confederation, and in the last of these, only in the two provinces of Salta and Jujuy. Forgetting for a moment the political divisions of the American republics, which have arbitrarily joined together such different countries and disparate races, we could say that this leaf is used by the descendants of the great nation of the Incas. It makes up the treasure of the full-blooded Indians and the cholos – the children of Indians and whites – and less frequently it is chewed by the black, the mulatto, and, rarely, the white.

In his chuspa (leather sack, made of a bladder or other material) the Indian always carries a certain supply of coca leaves, and with this he welcomes the new day and the setting sun, which was once his God. With all the attention lent to a cherished habit, he takes a small bunch of leaves, which may vary from one to two drams, and puts into his mouth a sort of bolus or cud called an acullico, to which he joins a small fragment of llicta.

The llicta is an alkaline substance made from cooked potato and bonded with rich potash ashes obtained from the combustion of many plants. Travellers are wrong to cite only the llicta of Chenopodium quinoa; for I have seen used, in addition to this plant, the woodlike torso of the buckwheat stalk, vine leaves and stipes, and a grass the indigenous call moco-moco (this grass, which I took back to Europe, was examined by my very good friend the distinguished botanist Dr Gibelli,13 who recognized it as Gomphrena boliviana). The llicta, by breaking down in the mouth, serves both to stimulate the secretion of the salivary glands and soften the leaves. I have several times used coca by chewing it either with or without llicta and have never found this alkaline matter to alter even minimally the coca’s overall effect, although using it I did occasionally have to endure a very annoying irritation of the mouth’s mucus-producing glands. The coca that grows in Peru has such tough leaves that one often must remove their veins in order to chew them, and for this reason perhaps the Peruvians must use quicklime instead of llicta. In fact, they carry it in a small silver and gold receptacle, and remove it with a small pencil-brush. This habit is very similar to that of the Malaysians, who use lime to chew betel leaves and arec nuts; perhaps this is what misled Don Antonio Ulloa14 to believe that coca and betel were the same leaf. To this day everyone knows that the latter substance – the delight of all the inhabitants of the Archipelago – is made of the leaves of the Piper betle.

I do not understand how Raynal15 can assure us that coca is eaten with a greyish-white, clay dirt called tocera; nor how, in the general history of his travels, La Harpe16 refers to llicta by the name of mambi. Never did I hear these words used in the lands in which coca is chewed, nor did I hear them recalled by people who had made long voyages into the interior of Peru and Bolivia. Perhaps these terms were used in the republics of the former Colombia, but with the data available to me I can neither confirm nor deny this.

The swallowed acullica is chewed slowly, wetted with saliva, and left to melt slowly in either cheek, while the juice is slowly squeezed out and drunk. The coquero17 is immediately recognizable because he resembles some ruminative animal or monkey who has hidden his theft of fruit in his cheeks. After a while, nothing remains of the coca but a stubbly mass from the woody webbing of the leaves, and the descendant of the Incas must always take care to place it above various monuments made by wayfarers, who set down a stone in the same spot as if to greet one another. This custom is performed with all the reverence of a religious rite. The most moderate coqueros consume between half an ounce and an ounce daily, divided into two rations, one for their morning labours and one for their evening rest. Few, however, are content with such a small amount, and are forced to accept it mostly by poverty, not lack of desire. An Indian may chew two, three, or even four ounces of coca a day without being called a drug fiend, and it is only when he takes six to eight ounces a day that everyone considers him a lost soul.

Scarcely has the Indian been weaned from his mother’s nipple than he is introduced to the favourite stimulant of his fathers; and even as a small child he is entrusted with a full day’s watch of the sheep or llama herd with no other provision than a little sack of coca leaves and a bit of llicta. While thus he leads the animals that constitute his sole paternal wealth over the bald rocks of the Andes, which are faintly vegetated here and there with a bit of moss or a rare tuft of pajonal,18 he chews the leaves that are his only food for many long hours.

Coca serves the native as a food and stimulant, and without being able, most of the time, to explain its action, he feels lighter in spirit, more strengthened and comforted in his ongoing struggle against the elements, and better able to withstand the harshness of his continual, often abasing labours. Without coca he poorly digests his potatoes (which freezing deprives of extractive materials), his charqui (dried meat), his mote, and his lagua; rough foods all made with maize; without coca he cannot work, or enjoy himself, or, in a word, live.

Imagine a small man with tiny feet and a very wide torso, obliged to live on very bad food and at an altitude ranging from 7,500 to 15,000 feet above sea level. In these conditions other men would scarcely survive; and he must live and continually work. He serves as a foot postilion, or mule guide, escorting for several leagues a traveller almost always mounted on a good mule and riding up and down the slopes at a quick trot with scarcely a thought for the poor Indian who must accompany him. Working at other times in the mines, barefoot, in the morning he breaks up the frozen mud mixed with a silver amalgam, and sweats, driven on in his labour, beneath a sky that would numb the heartiest. All these prodigies the Indian accomplishes with coca, and without it he rebels against his master and against life itself; and this everyone knows, because in addition to the usual terms of a salary, the hired man is almost always allotted a coca ration.

When the Indian must stand guard or walk many leagues or take a wife, all deeds requiring greater than usual strength, he raises his normal amount of coca, meticulously calibrating it to the expenditure of nervous energy he needs.19

Human nature is so constituted that in every clime and every country the next step to enjoying a pleasure is abusing it; and this is no less true of coca. The vice of coquear is, indeed, one of the most tenacious and invincible known to man.

The incorrigible coquero always has his acullico in his mouth and can be seen without it only when he is eating. He often sleeps with coca in his mouth. He forgets his own duties, forgets his family, and even takes from life’s most pressing needs the time and money to devote to his passion. If fortune has not made him rich, he works only as much as he needs to buy himself his cherished leaf, and, withdrawing into the solitude of the woods and mountains, lingers there, a prey to the delirium that inebriates him with pleasure. I knew a Negro who would vanish every so often from his master’s house for an indefinite period, and return only when not a single costermonger would furnish him, penniless and without credit, with the smallest dose of Bolivian leaf. I know a gentleman of the white race who, addicted to this vice, left for good his own family, and for long intervals could be found only in the densest forests, prey to the basest degradation. And so it is no mere metaphor when the Americans say, Fulano anda perdido por la coca.20

The coquero is self-sufficient; social ties, the most sacred bonds of affection, ambition, all life’s amenities are meaningless to him; his pleasure absorbs all others, and when, through money, labour, or fraud, he has come by a generous supply of leaves, he has before him a sure future of several days of happiness, nor does he seek anything else. To this summit of prostitution arrive, more than the Indians, the blacks, the half-castes, and the whites. Contributing to this fact is the varied effect this substance exerts on the different races. From my experience I can say that the pure-blooded native is the man least subject to the ravages of coca, the black the one who most readily succumbs to its delirium and mental alienation.

Sometimes the coca addiction is connected with alcohol abuse, the two combining to abase the man to the lowest degree, causing him even to lose any sense of who he is.

In America, coca, beyond its dietetic importance, has many uses in popular medicine. Its infusion is continually used in cases of indigestion, for stomach pains, for hysteria, for flatulence, and above all for the enter-algias of all sorts that in that clime go by the general name of colicos. In such cases, the infusion is administered orally or through an enema.

The horror the coca vice inspires in Europeans who have settled in America may perhaps have contributed to its limited use among the white race. Indeed, a ridiculous prejudice against it has arisen by virtue of which those who chew it are hidden away, as though to consume it by infusion were to place it beyond reproach, and the immorality of this act were confined to its chewing. I know, however, of a respectable prelate in Chuquisaca, less fastidious than others, who did not blush to present at his table, after the fruit, a silver platter full of greener, more fragrant coca leaves, assuring his guests that it brought him the best digestion in the world.

Two main sources provide us with the materials necessary for ascertaining the therapeutic impact of a substance: tradition, and the study of its physiological effects. The most valuable treasures of the pharmacy do not come from scientific divination but from one of the manifold tendencies of the instinct for preservation and the vagaries of chance, and in this the living art of the people has done rather more than medical science. We are left with the task of humbly receiving the legacy of time and of recording it in our name-rich, fact-poor protocols.

To classify a remedy, I, however, do not intend to find it some small slot in one of the many pigeonholes that vie for space in the thousand archives of pharmacy; I mean, rather, that one should study physiological effects, weigh advantages and dangers, exactly define its therapeutic limits, and finally try to counterbalance the findings of popular tradition with the results of science, to see where they overlap. If the physicians had had the patience to do the former before receiving every medicinal substance with open hands – and closed eyes – we would now find the ground we stand on less shaky, and could build ourselves a sturdy edifice.

To date, as far as I know, no physiological study of coca has been undertaken, and I offer the following remark as the first lines in a picture that men more learned and experienced than I will have the chance to complete.21

Until physicians provide us with an analysis of the Bolivian leaf, I have thought to set up experiments about its juices as extracted by chewing, because I was thereby producing only the leaf’s utterly inert wood texture, which put me in the exact situation of the Indians who use coca in this way.

When one ingests a dram of this leaf, it is rapidly steeped in saliva, and there is no need to follow the Americans in using llicta, which is excessively irritating to the mouth; and by the chewing, it is quickly reduced to a soft mass that easily allows the pressing out of the juice, which has a bitter taste at first, then a herbaceous one; gradually the cud of the coca loses its juice. Shortly after swallowing the salivary solution of the leaves, one feels a sense of well-being in one’s stomach that is neither hot nor tingling; it might be better compared to the feeling one has of having digested something well. On an empty stomach this sensation can elude many people, but when one chews coca after a meal, it is impossible for its beneficial effects to go unnoticed even by the least sensitive or observant person. In this instance, five or ten minutes after beginning to use the leaf, a wholesome exaltation announces to us that the digestive process is working more easily and rapidly than usual. This advantage is better noticed by those with low, difficult digestion. A young doctor in Milan, who found himself in this circumstance and who for years awakened in the morning with a filmy mouth and a white tongue, found such advantages to taking coca after meals that he never forgets it a single day and has given up cigars and coffee.

Coca has a most mysterious effect upon the stomach; it neither hastens digestion nor stimulates it, irritating it in some excessive way; I, taking it almost daily for two years, have never found that it irritated my stomach, even when I took a rather copious amount. It does seem slightly to excite the nervous system of the upper viscera of the epigastrium, removing any awareness of its activity or easing the process. I, for example, absolutely cannot occupy my mind after dining without experiencing headache and difficult digestion, and only when I chew coca or take it in a hot infusion can I engage in light reading after meals without taxing my stomach or brain.

Without being absolutely sure of this, I believe that coca aids in the secretion of the gastric juices; for when a large amount is chewed on an empty stomach, acid eructations follow. Llicta would probably bring the stomach’s acidity up to its maximum level, unless some foods might benefit from it for their own dissolution. When I took coca at breakfast with some granules of bicarbonate of soda, I never suffered acid eructations.

Habitual use of coca greatly whitens the teeth, and I have always found them to be quite magnificent in the Indians who have taken it daily for years. It is not uncommon to see octogenarians in Upper Peru whose teeth are now only a few millimetres tall through the wear of constant chewing, yet are otherwise exceedingly healthy. Contributing to this fact are certainly race and the alkaline llicta with which coca is consumed in America; but I have always noticed my own teeth to be whiter and better able to break through hard substances whenever I have chewed the precious Bolivian leaf for some time. I have been able to verify this fact several times in different climates of America and Europe. Convinced of the healthy effect of coca upon the teeth, I merely doubt whether and to what extent the leaf’s chemical nature and the mechanical effect of the teeth bear upon this fact. All organs are evenly perfected in their functioning, and the coqueros chew ten times more than others who use their teeth only for food.

When the first acullico of coca has been used up and one starts to chew the second, one feels a thirst that comes from a dryness of the mouth and throat, not from stomach irritation.

The abuse of coca exerts no other influence upon the first stage of digestion beyond that mentioned, and if the appetite diminishes, or rather one feels a less urgent need for food, one should trace this back to its overall effect, and not to a harmful effect upon the stomach.

Slight or non-existent is the action erithroxylon exerts upon the small and large intestine. Enteric digestion and the final action of the rectum suffer no modification by the use and abuse of coca. The faeces lose their foul odour, taking on instead the special smell of coca juice. The habitual use of high doses of coca may result in constipation.

Coca exerts a marked effect upon certain secretions. Shortly after chewing one or two drams, one feels a dryness in the eyes and the pituitary gland, which enlarges in proportion to the dose. This dryness is in truth produced by a weakness in secretion and precedes the slight redness of the eyes that later appears as a symptom of cerebral congestion. I have occasionally seen an increase in urine. Sweat appears only when a fever arises from larger doses.

Using a moderate dose of coca several days in a row, I noticed a small rim of pityriasis22 form around the eyelids; only by momentarily discontinuing my use of erithroxylon did I see it go away. I corroborated this fact twice in different climates and, never having suffered on other occasions from this harmless ailment, cannot believe that it was a pure coincidence.

Anyone not yet used to using coca can, after chewing a few drams of it, see certain spots of simple erythema surface on his limbs and torso, spots which are transitory and harmless; at other times one experiences a pleasant tingling in the skin and, with the urge to scratch, sees oneself redden more than usual, particularly at the least rubbing.

Sperm, then, is a very important secretion, for its relation to the entire nervous system and for the influence it exerts over health, and it may be excited by immoderate use of the Bolivian leaf. One must be fairly well addicted before erections increase in frequency and potency; but chewing a few drams a day and, to a far lesser extent, taking it in a hot infusion, ought not in the least to alarm the scruples of the more chaste; I would only bar its use to someone who had excessively demanding needs, and attempt to curb them with all the physical and moral anaphrodisiacs available. Anyone, on the other hand, with naturally weak organs I would advise to read and meditate upon the next chapter, in which he will perhaps find some useful advice.

Wishing to ascertain with exactitude the influence that coca has upon heart movements, I performed upon myself certain comparative experiments by which to measure its effect against that of other nervine foods and of hot water.

The circumstances of the experiments were always identical, and I made the observations with as much precision as I could apply, checking my pulse before having my drink, one minute after, and then every five minutes for an hour and a half. I went no further than this, mindful that, after this time had elapsed, the pulse stayed the same or slowly followed its usual inclinations over the course of a day, without further succumbing to any influence by the drink. The pulsations were always counted for a full minute and in a sedentary position, which produces an average rate for all the positions. During the experiment, I remained calm, and did not perform any action that might appreciably alter heart motions.

The water was consistently four ounces, the quantities of substances involved 88 granules, and the brew, consistently prepared in the same way and at the same time for the infusion, was 61.25°C, the temperature most people prefer for hot drinks. Only in the case of cocoa was a decoction prepared instead of an infusion. As for the substances, I obtained them while they were at their purest, and except for those with some question mark hovering about them, I procured them where they are produced and got them from thoroughly reliable sources.

Let me add once more that the outside temperature was almost always the same in all experiments, and I always conducted the experiments in the period between three and four hours after lunch, so as to choose the most opportune time and to make the experiments comparable in the respect also.

The immediate results of my tabulations, and of other small corroborative experiments it would be pointless to refer to, are as follows:

1. All hot drinks raise the number of heartbeats; the maximum rise, which almost always comes right after drinking, gradually ebbs until the pulse-rate returns to normal.

2. An hour and a half later, pure water almost always reduces the pulse-rate. This fact, which is also in certain rare instances verified for tea and coffee, occurs only later with these drinks.

3. The rise in the pulse-rate under the influence of hot water is followed by a state of exhaustion, when the pulsations are scarcely returning to their normal rate, and even more, when they are falling; whereas the other drinks give off no feeling of weakness even when the number of heartbeats has returned to the physiological number, or even diminished. In the fifth experiment, in which, after I took hot water, the pulsations, after the usual ascent, remained normal, I felt no illness, but it should be noted that the next evening I had chewed a half-ounce of coca, there by putting myself into a state of overexcitement. This fact, which at first sight may seem exceptional, confirms, rather, the physiological law that the causes of weakening are all the less active the more resistant the organism is to them.

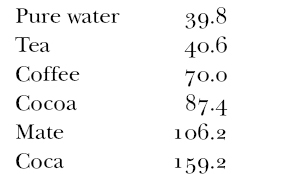

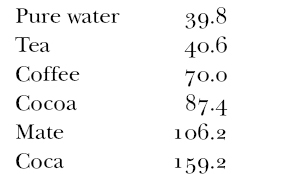

4. The rise in the pulse is somewhat different with different drinks, and can be precisely represented, according to the experiments I performed on myself, by the following numbers:

We see, then, that the erythroxylon infusion excites the heart four times more than hot water and tea and twice more than coffee, and the substance that comes closest to it is mate. Cocoa would seem to be only slightly more exciting than coffee.

5. The influence exerted by hot drinks on the heart varies according to an infinity of circumstances, and only now, I believe, can it be said that the pulse-rates rise the slower their effect is, and vice versa.

Coca, beyond raising the number of heartbeats when it has barely reached a certain quantity (between 100 granules and several drams), produces a temporary fever, with a rise in heat and number of breaths. Once under its influence I observed a temperature of + 37.5°C in the palm of the hand, and, on two occasions, + 38.75°C under the tongue. During the circulatory reaction, the face grows flushed and the eyes sparkle. Larger doses induce heart palpitations, and the congestion of blood in the vital centres is obvious. After three drams I experienced some moments of heart palpitations and cold hands and feet.

The highest rise in the pulse-rate under the influence of coca was 134 pulsations, whereas the normal rate is 65.

When the name of unknown regions has been expunged from the outlying parts of the nervous systems, a few words will suffice us, perhaps, to pinpoint the particular effect coca has on the cerebral-spinal axis and the ganglia network: at present, it would be an act of temerity, an idle classificatory whim, to seek to assign them a single term. I leave it to others to place them among the narcotics, the hypersthenias, the antispasmodics; had I to choose the least misleading among these words, I should stay with the first.

Shortly after one has chewed one or two drams of coca and swallowed its juice, one starts to feel a sensation of mild, and I might say fibrillar, warmth spreading over the whole surface of the body, while one sometimes feels a very gentle buzzing in the ears. At other times one feels the need for space and the urge to rush out as though in search of some wider horizon. One gradually grows aware that the nervous powers are waxing, that life is turning more active and intense; and we feel heartier, more agile, better disposed to all sorts of work. In certain people I have seen a state of drowsiness precede this awareness of strength, though this effect occurred only with stronger doses. With a bit of attention to apprehending the changes in consciousness in this first phase of cocal inebriation, one finds it quite different from that of alcohol. In the latter, nervous excitation is immediately accompanied by exaggerated or violent, and always irregular, movements; there is a general disordering of thoughts and muscular actions, whereas in the inebriation induced by coca it appears that the new strength imbues our organism in all senses and quite pleasantly so, like a sponge dipped in water. The delight of this phase is almost entirely bound up with the heightened awareness of being alive, and we, crouching inside ourselves, enjoy this period without feeling impelled to put the newly acquired strength to immediate use.

The sensitivity and excitability never increase: whereas the intelligence turns more active and we speak more vehemently, and feel, in a word, that the intellectual mechanism is more active, nevertheless, with our sensitivity either not having grown equally or often even having been blunted, we feel less apt to take on a higher level of mental labour. In this, coca works rather differently than coffee, and more closely resemblies opium. The precious coffea bean hones sensibility and the inner perceptions of consciousness, inducing us to search and find, and supplying the mind with many elaborate materials; whereas the Bolivian leaf vehemently arouses the whole brain without providing it with more abundant and more delicate sensations. Several times, for instance, I would put together, under the influence of the first doses of coca, some quite unimportant work, only to find it too slight to give vent to my mental overexcitement; and while my pen furiously raced across the page, I could no longer conceive new ideas nor at that moment imagine a more intense labour, nor a higher level to which my brain’s extraordinary state could be adapted.

With two to four drams, one begins to withdraw from the outer world, and one plunges into a blissful awareness of pleasure and of feeling intensely alive. An almost absolute immobility takes hold of all our muscles, and even summoning words is a bother, since it seems to disturb the altogether calm, tepid atmosphere in which we are immersed. Every so often, however, life’s very fullness seems to stifle us and we do burst out with energetic words, or feel impelled to deploy our muscular strength in various ways. I, who am by nature utterly inept at any gymnastic exertion, after four drams of coca feel extraordinarily nimble, and once jumped with both feet onto a tall writing desk so deftly and surely that I disturbed neither the lamp nor the many books piled upon it. At other times I felt I could leap over the head of the person near me.

In general, however, these excessive feelings are fleeting whims, and one immediately falls back into a blessed state of torpor, in which we think we could remain a whole day without moving a finger or feeling the least desire to change states. In this period of inebriation one never loses consciousness of oneself, but attains an ideal laziness, in all its perfection. One heaves deep sighs, occasionally laughs like a madman, and when one wishes to convey to others what one is feeling, the words come hard or confusedly at best. Several times I had to speak with extraordinary slowness, dividing the very syllables of my words at extremely long intervals.

Others say that the first doses of coca induce in them a sense of heavy-headedness and genuine pain; others feel their brain shrouded as though by a cloud; still others feel light-headed. All, at any event, among those who are examined by someone not under the influence of the American leaf present a blessedly still physiognomy, fixed in a peculiar smile that may even assume a kind of daze. All seem to be sleeping, but waver within those mysterious regions that divide wakefulness from drowsiness and sleep.

If, after passing through the first stages of cocal inebriation, one stops and goes to bed, sleep comes quickly and is very deep, interrupted at times by long intervals of drowsing with a peculiar feeling of well-being; almost always accompanied by the oddest dreams, which mount and straddle one another with amazing rapidity.

The particular drowsiness produced by three or four drams of coca can, in certain individuals, last for more than a day, but it wears off without a trace. Coffee, tea, and mate curtail this state, quickly bringing back the customary activity of the brain and nerves. In America everyone thinks that coca can cure alcoholic intoxication, and vice versa. I admit to the former case because I have witnessed it several times, and because the very pronounced digestive power of this leaf takes away one of the most distressing complications of alcoholic drunkenness; but for the moment I refuse to believe that wine can remove cocal intoxication, having never witnessed this, nor having reason to believe it could happen.

The highest dose of coca I ever chewed was eighteen drams in a day, of which I consumed the last ten in the evening, one after another. This was the only time in which I experienced the delirium of cocal inebriation to the ultimate degree, and I must confess that I found this pleasure far superior to any other physical ones I have ever known.

At the outset, until I reached eight drams, I felt the usual effects of a kind of fever pitch of excitement, a pleasant torpor, and a slight headache; but shortly before I reached ten drams my pulse had already climbed to 893 and I felt an indefinable exaltation, which I somewhat hesitantly described with these words: ‘I do not know if it is I who hold this pen in hand … I speak and hear my voice echo as though it were not mine; my hands are cold, I am tingling and feel only a slight ache. The skull bones seem to want to crush my brain …’ Fifteen minutes later my pulse had reached 95 beats.

A half-hour later I chewed another two drams of leaf, and my pulse instantaneously soared to 120 beats. I then began to feel a sense of extraordinary happiness, dragged my feet as I walked, distinctly felt my heart beating, and could write only with the greatest difficulty.

Over the next two hours my consumption gradually reached two ounces of coca, and I felt deep happiness. My heart palpitations had ceased, but the pulse remained at 120 beats, and I was lying down with a divine sensation of a more active, fuller life; then, roughly a quarter-hour later, after taking the two last drams, I started to shut my eyes involuntarily, and the most splendid and unexpected phantasmagoria began to pass before my eyes.

At that moment I had full self-awareness yet seemed isolated from the external world and saw the most bizarre, splendidly coloured, and splendidly shaped images one can imagine. The pen of neither the deftest colourist nor the fastest stenographer could for a single moment render those splendid apparitions, which straddled one another in the most disconnected fashion, at the whims of the most unbridled fantasy, the most fertile kaleidoscope.

A few moments later, the swiftness of phantasmagoric images and the intensity of inebriation reached such a level that I sought to describe to a colleague and friend near me at the time the full felicity now sweeping over me, but my words were so vehement that he could jot down only a few of the thousands I was shouting at him. I quickly fell into the gayest delirium in the world, but one in which I lost no consciousness at all, because I extended my hand to my friend – only to discover that the pulse had reached 134 beats.

Some of the images I sought to describe in the first phase of my delirium were full of poetry, and I mocked those poor mortals doomed to live in a vale of tears while I, carried aloft on the wing of two coca leaves, was flying through the space of 77,438 worlds, each more radiant than the last.

One hour later I was calm enough to write these words in a steady hand: ‘God is unjust because he has made man unable to live always cocheando, I prefer a life of 10 years with coca to 100,000 … (and here there followed a line of zeros) centuries without coca.’

I could not, however, manage to resist the desire to see the phantasmagoria repeated, and took two drams of coca, which I chewed in a real frenzy. The images still appeared, but I was overwhelmed as if by a nightmare – truly terrible ones, full of ghosts, skulls, satanic dances, strangling victims … Gradually, however, they grew calmer, more serene, to the point of reaching the most aesthetic ideal of art and imagination, and in this state of calm I spent three hours without my pulse ever falling below 120.

Three hours of tranquil sleep restored me to the life of daylight, and I could move on to my usual occupations, feeling that I could study more assiduously and without anyone being able to tell from my expression that I had experienced sensations of a voluptuousness I would previously have thought unattainable.

For forty hours I remained under the influence of coca without eating any food and without feeling the least weakness. From this experience I realized very clearly that the vice of cocal inebriation can be unstoppable, and that the Indians, who still travel on foot, can, with their treasured Bolivian leaf, live for three or four days without taking any food. What most amazed me in this experiment is that I felt neither exhaustion nor languor, although I had used up so much vital energy in just a few hours.

The day after inebriation I felt a pleasant warmth throughout my body and felt mildly constipated. Thereafter, my digestion was excellent.

Another time, chewing coca after my meal, I began to see phantasmagoria after the sixth dram, and this continued for over three hours, during which time I chewed another two drams. Immersed though I was in a state of ineffable bliss, I still had extremely clear consciousness and could clearly delineate some of the bizarre images that passed before my eyes swift as lightning. Here are a few: note that for every one I could set down upon the page, ten others eluded me in their too rapid succession:

… A grotto of lace beyond the entrance to which one could see at the other end a gold tortoise seated upon a throne of soap.

… A battalion of steel pens battling an armada of corkscrews.

… A glint of glass shards perforating a wheel of Parmesan cheese crowned with ivy and mulberry leaves.

… A saffron-coloured inkpot out of which rises an emerald mushroom lashed with rose-coloured fruit.

… A ladder of blotting paper lined with rattlesnakes, down from which are leaping red rabbits with green ears.

… Flowers of striped porcelain with stamens of burning silver.

… Looms made of tapers, on which a group of cicadas are weaving various pine plants made of sulphur.

The next day too after this experiment I felt more energetic than usual, although I had slept but an hour that night.

To sum up in a few words the physiological effect of erythroxylon, let us say:

1. Coca has a special stimulating effect of some aid to digestion.

2. In a high dose it raises body heat, pulse, and breathing, also inducing fever.

3. It can cause some slight constipation.

4. In mild doses (1 to 4 drams) it excites the nervous system enough to make us more prone to muscular fatigue and gives us a very high resistance to any altering external causes, thereby creating in us a state of blissful calm.

5. In higher doses, coca produces truly delirious hallucinations.

6. Coca possesses the very rare quality of exciting the nervous system and letting us enjoy, through its phantasmagoria, one of the greatest pleasures in life without draining away our strength.

7. It probably reduces certain secretions.

Coca’s hygienic applications are easy to deduce from its physiological effect, and in America have long been determined by many centuries of experience. It remains to be adopted in Europe as a genuine treasure of the New World, on the order of opium, and the bark of a country common to both substances, Peru.

A hot infusion of leaves is the healthiest drink to take after a meal, particularly when one has a weak stomach or when one has somewhat exceeded the bounds of temperance.

Coca tea, when taken regularly, offers the huge advantage of mitigating excessive sensitivity, so that I recommend it for vaporous and sentimental creatures of the fair sex.

Coca chewed in a dose of a few drams makes us resistant to cold, dampness, and all the altering causes of climate and fatigue; so one must warmly recommend it to miners and travellers in swampy terrains and polar regions.

Coca fortifies us against heavy fatigue and counteracts the exhaustion of force that follows our exertions of nervous currents – I unhesitatingly consider it the most powerful nutrition for the nerves.

Taken in high doses it can make life more cheerful, bringing with it hours of true happiness that need not offend the most scrupulous morals. Wine, consumed at times to the verge of drunkenness, does not make us guilty; no more does coca, chewed to the point of inducing highly pleasurable phantasmagoria, turn us into addicts.

Coca in high doses should not be used by those who suffer from cerebral congestions or tend toward apoplexy. Used in infusions, it is harmful to everyone.

The abuse of coca, if prolonged over years, may produce idiocy and dementia. I have never been able to detect any trouble in the functions of the digestive organs.

In those blessed times when the sharp sword of dualists, cutting with a single stroke through the awful tangle of pathological doctrines, sent two fine words aloft, coca might, with the greatest of ease, have been marshalled into one or another column of therapeutic aids. Yet I, out of an unconquerable horror of words that do not represent things or that tyrannically legislate over facts, gladly forswear any facile efforts to systematically baptize this leaf, settling for pointing out its practical usefulness in medicine.

Having always noticed how white the teeth of coca users were, I naturally thought of using it as a dentrifice, particularly in the north of the Argentine Confederation, where the condition of most people’s teeth tends to be terrible. I therefore recommended that they wash their mouths once or twice a day with a concentrated cold decoction of coca, and rinse their mouths often with the powder of the leaves, either on its own or mixed with rose honey. I have always stood by this advice, above all when the tooth cavities are caused by a scurvy altering the gums as they gradually recede. Since coca, however, though very useful in these cases, does not seem to displace other known remedies and remains quite expensive, I would advise that it be used in Europe only in those cases of gum softening that often accompany slow stomach infections, or when the other known substances have proved ineffective. To anyone who wishes to use it for this purpose, let me point out only that it has the advantage over bitter barks and harsh-tasting roots of cleansing without irritating and of not having an unpleasant taste.

Beyond cleaning the mouth and teeth with it, I have never used coca externally in any way, nor can I yet say whether its various preparations might act as a narcotic when applied to the skin or the outermost mucous passages.

Coca’s most important medical uses can be deduced quite naturally from its physiological action upon the gastroenteric mucous membranes and the nervous system.

The Bolivian leaf acts in two quite different ways upon the digestive organs, and up to this point they have not been combined so harmoniously into any other remedy. It eases the digestion, animating it when it is slow and readjusting it when it has been altered; at the same time, it dulls the sensitivity of the gastroenteric mucous, often easing even the strongest pains.

In general, the substances that stimulate the stomach to greater activity often tire it and almost always exhaust its physiological powers, even when they do not induce greater irritation in it, or a slow phlogosis. This is why their action is more or less dangerous, and in a healthy therapy their use is seldom indicated. Coca, on the other hand, mysteriously reanimates the stomach’s digestive activity without ever irritating it; nor do I recall having seen, even once, either in myself or others, the well-known symptoms with which the very delicate viscera rebels against anyone who would force it to work without first protecting against its festerings. While practising medicine for almost four years in tropical countries, I had on several occasions to treat genuine phlogosis-induced stomach irritations produced by the abuse or even just use of mate, coffee, or tea – irritations I never found among the coqueros. The Europeans who settle in Upper Peru and the northern provinces of the Argentine Confederation can almost never resist their preference for coffee, and almost always feel its bad effects on the stomach and on the nervous system as well; only after many sins of persistence are they persuaded to consume a coca infusion after a meal, temporarily abandoning their delicious-smelling coffee.

I have recommended coca to young and old, healthy and convalescent, Indians, blacks, and whites of many nations, and to hybrids of all colours; I have used it in one or another hemisphere, in countries at sea level and at altitudes of thousands of feet, and I have no hesitation in saying that it is superior in its digestive powers to tea, coffee, and other, obscurer hot beverages served at the end of a meal.

Those fortunate enough to have a good belly would be wrong to replace beverages they prefer with a new and perhaps less enjoyable one; but to those whose digestion is slow, difficult, or painful, I warmly recommend use of this infusion for many consecutive months. It can be prepared with a denaro or half-dram of leaves in the same way as tea is brewed. A great many people prefer the latter infusion, since it is less strong and more delicate.

I would advise gentlewomen and the highly-strung to blend their coca with orange leaves, preferably of the bitter variety.

The narcotic or antispasmodic action of the American leaf upon the stomach and the intestine is very pronounced, and leaves even the most sceptical physician free of doubt. Gastralgia and a whole range of ventricular neuroses, simple enteralgia, colic pains, and flatulent enteralgia are almost invariably overcome by a coca infusion. I have always found it to be of great utility against the diarrhoea that often attends bad digestion and is almost always accompanied by very distressing pains.

In the case of enteralgic or colic pains, I administer it orally or through an enema, making sure that the infusion passes through the rectum in a more concentrated form (one dram to every four ounces of boiling water) and in small quantities, lest it be expelled too soon. If a first injection is not enough to calm the pain, it should be repeated at half-hour intervals, using the same leaf for two or three infusions. Since I have never seen a single case of saturnine colic in South America, I could never determine what benefit coca might have for wiping out the fierce pains this sickness brings.

I have never used it for vegetal colic. I am inclined to set great hopes on its beneficial action against Asian cholera, because it combines great stimulation to the nervous system with a very healthy influence upon the gastrointestinal tube.

Except in cases of acute inflammation of gastrointestinal mucus, I encourage coca use for dyspepsia, gastralgia, enteralgia, and all spasmodic and painful ailments of the digestive organs. A slight gastric or enteric irritation or liver blockage is never sufficient cause to counterindicate use of this leaf. One should never forget coca in regard to pepsin, and indeed one should closely study the cases in which one or another was used.

In convalescence from long illnesses, when one must resort to tonics while fearing that they might not be tolerated, it would be advisable to consider coca first. It has the advantage of restoring the convalescent’s strength in two ways, by easing the digestion and invigorating the nervous system.

The action of this substance upon the cerebral-spinal axis is even more important and mysterious than that which it exerts upon the digestive organs, and warrants deep study. The few observations that I can offer are accompanied by the keenest desire to be illuminated by my colleagues, who by trial and retrial will probably be able eventually to obtain precise therapeutic indications for coca, thereby expanding the very narrow circle of my doubts and convictions.

Whether the erythroxylon leaf suspends or slows the incessant destructive motion of the tissues, as the distinguished Lehmann proved for coffee, and whether this leaf rouses the organism’s neural battery to great action, it is true at any rate that coca sustains life by making man capable of greater expenditure of his nervine force.

The intelligence is revived only at the outset by the effect of coca, and only when it is taken in small doses; later, the mind comes to a state of rest in calm contemplation. The muscles are better able to sustain the incessant contraction, and the whole organism has less need to be restored by foods. The coquero eats little without losing weight, and the coca user who does not overindulge can withstand humidity, cold, and all other altering causes considerably better than a non-user.

With these facts in mind I have used coca in all cases of great nervous prostration; of general weakness, hysteria, hypochondria, and tedium vitae. On occasion I have administered it in highly concentrated infusions, at other times in hydroalcoholic extracts in doses of 5, 10, or 20 granules a day, depending on the cases.

Given all the obscurity that surrounds the nature of cerebral and nervous disorders, the physician should proceed cautiously in reaching a diagnosis, but, once sure, should indicate coca use without hesitation or fear. It is a remedy that exerts a slow but deep effect, and when used over a long period of time can permanently modify the nervous system. When there is real congestion, or phlogosis, or organic damage to the central nervous substance, coca is dangerous.

I have used coca in cases of mental alienation, and warmly recommend it to physicians who use opium to treat melancholia. In high doses it may have the same advantages as poppy juice, but with added beneficial influence upon the stomach. But here let me simply set a stone marker in the road and hope to return to this subject another time.

Coca should be given in all those cases in which there has occurred a functional disturbance to nervous life, stemming apparently from a state of weakness or perversion. Simple spinal irritations, idiopathic convulsions, constitutional dulling of sensitivity are always or almost always improved by the action of erythroxylon.

I have a strong desire to try administering it in cases of simple chorea,23 hydrophobia, and tetanus.

These indications are quite tentative and may well seem insufficient, but one should not be too demanding when one recalls that to this day the effect of opium and the cases in which it should be used are still subject to debate, and coca, as far as I know, has never as yet been used in Europe.

If my studies have entitled me to briefly describe the action of coca upon the nervous system, I would like to relate it to that of opium and the antispasmodics, while recognizing that it differs from all other hitherto known remedies.

As a substance that generates nervous strength, I rank coca superior to all others known to us thus far; and to a man in imminent danger of losing his life through nervous exhaustion, I would give either a tincture of it or a strong dose of its extract.

In America there is no one who doubts the aphrodisiac action of the Bolivian leaf, and I myself, if I wished to believe in certain observations I have amassed, would have to concur with universal opinion. Persuaded, however, that doubt permits science far greater advantages than affirming without a firm basis of certainty, I shall say only that on some people coca unquestionably acts as a stimulus to the genital organs.

The American nations that use coca are surely among the world’s heartiest in love’s combats, and if modesty permitted us to make a gynodynamometer we would see its highest degrees reached among the descendants of the Incas, who maintain the most enviable prowess into very advanced age. I have also observed certain cases of daily or nocturnal pollutions from weakness of the genitals improved and cured by the chewing of coca after dinner, and have often heard, from various Europeans of different countries, that their erotic desires were reawakened by varying doses of erythroxylon. I never gathered enough data, however, to determine with any precision what role the use of coca and the influence of race played in the genital vigour of Bolivians.

Erythroxylon rouses the genital organs to action, stimulating the spinal axis or boosting the circulation yet never irritating the mucuous of the bladder or the urethra, so that if its aphrodisiac power were once recognized, the power would be that much greater thanks to its two precious qualities of aiding the digestive organs and doing no harm to the genital-urinary apparatus.

Of all the functions regulated by the brain and the spinal marrow surely none is more capricious than genital activity; for this reason there is so much variance of opinion among physicians and non-physicians over the relative value of aphrodisiacs. In the Orient, where a large part of life is spent among the embraces of the harem, blissful sybarites often urgently demand that foreigners prescribe for them certain aphrodisiacs. A renowned traveller, embraced with urgent entreaties by an old man in Indonesia who only that day had married a very beautiful young girl, in order that some remedy might help him overcome his terrible fears of what must take place on the first night of pleasure, prescribed for him two granules of muscat with calomel. When this traveller passed through the same land several years later, the good native, overjoyed, showed him a sprightly little boy, saying that he had named him calomel. In this case, then, even mercurous chloride had gained fame as an aphrodisiac – proof of what a supreme influence the imagination exerts upon the reproductive function. For the Orientals, opium, asafoetida,24 hashish, and swallows’ nests are aphrodisiacs, whereas in South America liquors made from corn, guaranà, and coca are considered such.

Until we know the chemical composition of coca, I advise using it in infusion form, or, better yet, for those so willing, chewing it in a dosage of one dram a day. If there is need for a profound action upon the nervous system and the patient refuses to chew it, one can resort to a powder of the leaves (in 1–4 dosage) or to a hydroalcoholic extract, which can be given daily in from five to ten granules, with a gradual rise in the dosage.

The coca tincture is a very active preparation.

I have always blended coca only with aromatics in the infusion, and with subnitrate of bismuth when I was taking the extract in pill form.

The action of coca varies somewhat with different individuals, and the first sign of intolerance is a sense of heavy-headedness, which in certain cases can turn into a genuine ache. The careful physician should encounter this drowsiness or delirium only in very rare cases.

I do not know what place coca should be assigned in the treasury of therapies; I do know that it is likely to be championed or contested, rousing excessive enthusiasm or excessive indifference; I believe, however, that it will remain, with its other siblings, among the host of heroic remedies that often change country and name, but which sensible physicians never remove from their pharmacopoeiae.

[Chapter 5: Practical Observations on the Therapeutic Action of Coca]