The Symphony of the Book [– Journey from Florence to Bombay – Notes from My Notepad – Port Said and Suez – The Red Sea – Aden – Life on Board – In the Indian Ocean – The Last Day on the Singapore – Hymn to the Earth and Anathema to Cremation]

Surely there is no one among us who in childhood did not dream of India and in youth did not yearn for it. The Thousand and One Nights, Golconda, nabobs, elephants, bayadères1 are part of popular poetry in the theatres, and come to us at night in mysterious dreams. We find something of India in our brain even before it has been born in outer life; we find fragments of it in our dictionaries, on our skin, in our words, everywhere. A child in Lombard says; Va a Calicut, go to Calcutta; the man of the people wears a shirt of Madapolam cotton; our fine ladies cover their shoulders with cashmere, on their breast gleams a sapphire, on their fingers a little piece of heaven made from Tibetan turquoise. The words with which we display our feelings have their roots in that faraway land of blazing sunlight and intoxicating perfumes. Why have we not the same sympathies for America? Has it not deep virgin forests? More gigantic rivers? Has it not, perhaps, also perfumes and flowers, and if not Golconda, caskets-worth of gems even more brilliant in its hundred thousand hummingbirds? Java too is more beautiful than India, Africa too has its aesthetic mysteries and the dangerous, fatal seductions of virginity. But America, and Java, and Africa are not India. India is the country from which we have come; India gave us the blood, the language, the religion, and the bread of daily life, and that other, golden bread, as necessary, nay, more necessary perhaps, than the first, which is the ideal. India exerts a charm upon us that no other land on earth can have. That is because we are all fragments of it. In no other instance do we see atavism work more powerfully within us. Thus I too, in childhood, in boyhood, in youth, dreamed of India, dreamed it as you did, as all do. And when, having grown into manhood, I devoted my whole being to studying mankind, as a physician, a pathologist, an anthropologist, I felt it was my duty to see that problem-ridden land. And I was and remain happy to have done so, as one is happy after satisfying any long-harboured, ardent desire. The philologist may have a profound knowledge of Sanskrit, the historian may solve great problems, without setting foot in India. The anthropologist must go there. Apparently this need is generally felt, too, because, on finding Haeckel2 there, I learned that Lubbock also was expected.

Half a century ago, Jacquemont3 took eight months to go from France to Calcutta; today you can go there and come back, in the same length of time, after a stay of six months traversing that entire land so rich in people and problems.

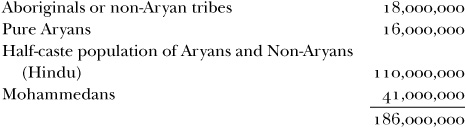

Two hundred and fifty-two thousand million people, all the climates in the world, all the colours of human flesh, Buddhism, Brahmanism, Mohammedanism, and every form of the religion of Christ, plus the wildest fetishism; Buddha, Brahma, Christ, and the Sun. All the material needed to resolve the largest questions of anthropology and ethnology.

The fruit of my voyage to India is this book, which has no claim beyond the very modest one of limning in broad strokes one of the most fascinating countries on earth, and of enticing the reader to go there, be he a man of science or an artist, a businessman or a touriste. All will experience there new emotions, troves of observation for the present, precious memories for the future. Beyond this book I shall publish four scientific memoirs which, assembled under the title ‘Studii sull’etnologia dell’India,’4 will form a volume illustrated by original photos I took during my voyage.

To make a book about India, however, I should like to be a musician, to be able to write a symphony that could serve as a preface to my volume.

Music is the only art that can generally express the indefinite, the immensity of sensations that India arouses, it is the only art that could speak of all the warm sensuality and the interlacement of great, exalted, multiform thought to which we are borne in visiting that faraway land; a country of cholera and elephants, the most beautiful orchids and tigers, and where almost 300 million people of all colours throng like ants in an anthill on the Queen’s coronation day.

Excess is the dominant note in India – too many people and too many animals, too much heat, too-high mountains, too much wealth and too much poverty, too much senility and too much childhood, too many colours and too many odours, too many fevers and too many loves, too many dead and too much life. We poor lukewarm men of the temperate zone feel overwhelmed, inundated by too many sensations; one is dazed, dazzled, wearied. Inside and out, one is forever sweating.

Temperance, modesty, shame, thrift are all exotic plants in that land of fire, and there we are led at every turn to envy its natives. I should therefore be writing a symphony in the key of the excessive, and then I would want to take you inside dark, horrid temples, with cows and peacocks and mendicant priests, and elephants covered in gold and silver, and gleaming gems on the breast of babes, and princes who have on their garments millions in precious stones, and coolies5 who live on four lire a month, and black people, naked, always gleaming with coconut oil or sweat or both at once, and then an orgy of naked flesh, well shaped, not deformed by layers of dress and trousers, and then multicoloured apparel that veils, covers, but does not hide the human body, speaking and feeling, rather, with the man who uses it, and then the grotesque in the saint and the gigantic in the awkward, monkeys that are worshipped and holy men who don’t budge from their spot for thirty years, and monkeys kept at the expense of the state and hospitals for cats, and dogs and ravens and snakes and elephants, crocodiles, rhinoceroses, buffaloes cavorting in fevered lands and bamboos tall as towers and forests of magnolias and rhododendrons big as chestnut trees, and bayadères who seem epileptic, and faces dulled by opium and teeth corroded by betel and mouths that seem to spit blood everywhere, and mountains among the tallest on the earth, and shops smaller than a cupboard; and a pandemonium and a dithyramb of gleaming things, grotesque things, things very big and very small that seem some colossal masquerade dreamed up by a delirious Victor Hugo.

But I am no musician, and the symphony will not be written. I shall, instead, make a simple narration of my trip, drawing it from the jottings in my notebook and alternating it with studies on the Hindus and their ways. I make but two claims: scrupulous veracity in every detail, and the clear distinction between what I myself saw and how much I learned instead from the written word of books and from the talk of the many Englishmen I met in India and who had resided there for many long years. […]

In Bombay – The First Scent of India – Watson’s Hotel and Indian Hotels – Servants and Their Delights [– Bombay Described by a Hindu Poet – The Market – The Animal Hospital – The School of Arts – The Black Town and Dwarkanath – Bombay’s Bazaar]

Before you have barely disembarked at Bombay, you sense a smell that is new to you, utterly peculiar, that comes close to that of a blend of musk and spices. If you open the window in the morning, it wafts into your room as the first greeting the land of India gives you; you smell it more strongly where the indigenous population gathers, probably owing to the sandalwood and other sacred scents burned in the houses. In Madras and in general through the south of India, the smell of the place is, rather, one of coconut oil, and in the stations, the districts inhabited by the natives, and the market, it smells its sharpest, almost seizing you by the throat.

For those with delicate senses of smell, many countries have a characteristic odour, and I recall, among the best known, that of fish oil in Norway, of fog and fossil coal in London, and of gatinga (the Negroes’ sweat) in Rio de Janeiro.

The smell of the air, however, is not what strikes you most when you land at Bombay. It is the fantastic spectacle of a half-English, half-Indian city, with a population among the most multicoloured in the world, where human flesh is presented to you in all its pigments, and human garb in all styles and shapes, all the hues of a carnival or a Venetian palette. It is a museum of races, an exposition of ethnic types, a kaleidoscope of dazzling shades and bizarre figures composed for you – and decomposed before your eyes. Woe to you if, in that magical city, in your first days you have kept that intensely calm sensitivity you enjoy in our cool continent of Europe. You will be intoxicated and feverish, as I was at the age of twenty-two, on landing for the first time on the coast of Brazil. Instead, luckily for your nerves, the gentle weariness of the tropics embraces you on your first descent into India, and in the preferred horizontal position that you immediately assume, you peacefully see pass before you the magic lantern of the white Parsis6 having stovepipes for hats, the naked coolies, the pariah girls black as ebony, the red, yellow, violet turbans, with or without a horn, with or without a tail, and horses and coaches and palanquins; and you hear a confused murmur of all the world’s tongues, which seem to collide unwittingly, like dialogues between drunken people, lingering in the air.

My lodging is the Esplanade or Watson’s Hotel, one of Bombay’s best; I have taken a small room on the fourth floor.7 It costs me two rupees less than if I had chosen the second floor, and one less than the third. If I were to go up to the fifth, I would pay one less than that. As for board and service, I am treated the same as the other guests; that is, I may eat all that is available in the kitchen and appears on the menu. I could, for example, if I were to try emulating Gargantua, consume ten plates for lunch and twenty at dinner, without counting the tea and coffee with bread and butter in the morning, and the bath, which I am free to take whenever I wish. For all this, by God’s grace, I pay a mere six rupees a day.8

India’s hotels cost little, but are the most hilarious thing in the world. When you scold the English for their deplorable state, for the utter lack of comfort found in their Indian hotels, they start to laugh and shrug their shoulders. They frequent them only by chance and for very few days at a time, having homes of their own, or finding easy accommodations at the houses of friends or in their clubs. Then too, they always go about with one or more of their own servants. Yet I, who travelled through all of India with no servant, something as remarkable as a European travelling among us without valise or trunk, experienced the delights of Indian hotels.

At Watson’s Hotel, for instance, these things happen: at one moment you could have dropped dead and no one notices (they do not have alarm bells here), at another, you are assailed by a cohort of servants that won’t leave you in peace. One day when I received many visits, the visitor for chamber pots entered the room four times within an hour to see if I needed his help, naively lifting the bed-covers to verify this fact. My indignation was all for nought, since he understood not a single word of English. Another time I was wakened ten times between five and seven in the morning, five times to offer me a bath, which I had said I did not want, and five times to offer me a tea I had declined.

Pum, pum! ‘Will you take a bath?’

‘I don’t take a bath this morning.’

Pum, pum! ‘Will you take a cup of tea?’

‘I don’t take tea this morning.’9

At the tenth knock I leapt out of bed in my nightshirt, and made a terrible scene in the corridor, yelling and shouting and cursing in English, Milanese, and every language I could muster. Apparently they understood, since I was left in peace.

Words cannot describe the dinner scene at a table d’hôte in Watson’s Hotel. An immense room, more than a hundred or even two hundred people, all Europeans, at table. The punkahs (huge fans suspended in the air and moved by a coolie posted behind the door) are all waving together, scattering menu cards and napkins, and blowing the hair of those who have hair and wear it long. Behind every seated person a servant, in addition to the hotel servants, who must number at least fifty, and who come and go, ask without receiving a reply, and reply without being asked. It is the dining room of Watson’s Hotel that first gave me a sense of what took place at the Tower of Babel, that famous day when it pleased the Lord God to prepare so many thesauri for the study and pleasure of the future philologists of Europe.

Those servants ought to have been there to serve, and indeed, anyone who has a servant of his own reads the menu and orders him off into kitchen to fetch the desired dish. This process is not quite so smooth, however: for the private servant,10 dispatched into the kitchen, finds many other private servants who, like him, want to bring their master the best portion of said dish, so they fight, with words or fists, with or without mercy, depending on their respective temperaments and relative breeding: but sometimes two servants at once want the same good turkey thigh, and both grab it, until it falls onto the floor and a cat snatches it. Meanwhile, the table companion, who is hungry, waits with philosophical patience for the dish he has requested and envies his neighbour who, by not having a private servant, has all at once received four turkey thighs from four different servants. The slowness of return of the dispatched man depends at other times on such incidental causes as his finding a comely servant-girl in a corridor.

All things considered, however, he dines best who has his own manservant. I, for example, who did not have one, once asked four servants in a row for beer, only to be told, ‘Private.’ I had mistakenly turned to private servants. On another occasion, by the law of compensation, I asked for two eggs to drink, and my cry of hunger, received by five hotel servants with nothing to do at that moment, resulted in my having, a moment later, ten eggs before me. Add to this that the hour of the table d’hôte is so elastic that, while you are eating your soup, your neighbour to the right is already having his cheese, and the one on the left his entrée. Add the multicoloured colour of all those servants, the clinking of glasses, the clash of plates and knives, the shouting of the help, the calls of the hungry, and the sighs of the patient, and I assure you the scene is worthy of the pen of Rabelais or Yorrick.

Nor do the consolations of a first-class Indian hotel end here. One night in Watson’s Hotel I awoke, hearing a noise as of teeth gnawing upon something: I turned on the lamp and saw a large rat fleeing away, dragging off with it one of my shoes. The hole through which it had entered, though, was too small, and it left its loot with a break big as a scudo.11 I hung my shoes on the nail of a picture and calmly went back to sleep. Travelling in India in the wintertime, I did not encounter the famous land bloodsuckers, nor did I see snakes roaming about loose, but I did have dealings with rats on several occasions.

In the Deccan in 1878–9, some rats destroyed whole harvests of sorghum, devouring everything. It was the Golunda mettada, of which Elliot spoke half a century ago.12

But to return to the servants. I wished, and managed, to travel throughout India without any servant; but I would advise you to take one. Among the other fine things you cannot do without one is to be invited to dine, since even in the host’s house you must have your servant behind your seat, so that he can go into the kitchen to get you your food. I dined more than modestly only in the house of governors and kings, or Italians and foreigners kind enough to have the heart of kings; there, I was always served by the of those who had invited me. […]

[The Peculiar Way I Began the Year 1882 –] Journey from Bombay to Madras – Indian Railways and Cold Showers on the Train [– Madras and Its Hotels – A Tragicomical Boarding in Madras Bay – A Quick Presentation to the Reader of the Town of Madras]

[…]Wednesday, 4 January. I awaken at 4:30 and find myself among cultivated plains of sorghum, tobacco, cotton, and the castor-oil plant. Here and there are groups of Acacia arabica, one of the commonest plants in all of India. A village with Muslim tombs. Every so often there rises from the plain a conical hillock with ruins of ancient fortresses.

At a station I see an old black woman with her face and arms dyed yellow. It is one of the most horrid pictures yet painted with the human palette.

Over the Deccan Plateau, and at a station I buy Hyderabad currency.13 As though as an antidote to the old black woman, I see a young Indian woman almost naked, who smiles in the chaste and maidenly pride of her bronzed limbs. I watch her with an eye perhaps too European, for she, blushing as well as bronze can blush, draws a veil across her shoulders and drapes herself like a Greek statue.

At Cooty I marvel at many stark white houses, so tiny one might think they are a wooden village erected out of a Nuremberg toy-box. The men are all shaved two-thirds up to the crown of their head, and the remaining hair is gathered in a ponytail. The women have hair so black and sleek with coconut oil that it flames into a shade of blue I have never in my life seen.

We are in the first days of January, but the heat is tremendous. I allow myself the luxury of going into the small room annexed to every first-class car, and there I take a cold shower, while from the windows I see fleeting groups of palms and acacias. It is a new pleasure, worth a voyage to India.

One travels very well and inexpensively in Indian trains. A first-class car has only four seats, and if you are three friends travelling together you can be sure to be left alone. And the four seats change into beds at your pleasure, and you have desks and blinds and blue-tinted glass lest you tire your eyes in the garish light of the tropics. Every white-coloured car is protected from the sun’s rays by an awning and has a double covering, across which, in the hottest summer months, a sheet of cool water runs. From the car you enter the water closet, where you can take a shower or a cool cleansing sponge-bath. Baggage is expensive, but travelling in first class you can carry gratis as much as you desire in your car. You must always travel in first class, however, unless you want to find yourself in contact with not always clean Hindus, who are wont to travel in second class. There are cars for ladies only (i.e., Indian women) in the third class as well, and there is also a fourth class, in which one travels for just a few cents. The Indians travel a great deal and love the railways, and a train in India accordingly is one of the most picturesque spectacles you can imagine. Colours you would find only on the wings of parrots or in a country church consecration feast; as many physiognomies as Noah gathered into his ark; and if by chance you come upon a car for ladies only, when the train has halted, you see as many marmoreal and sculptured feminine bosoms as you can dream on for a good long while. At the stops, a Hindu black as ink runs bare-legged along the cars, shouting in a nasal voice, Pani, pani (water, water), and you see a hundred naked arms extending jars gleaming like gold to receive the water. […]

From Madras to Metapollium – The Nilgiri Mountains – My Toda [– The Coconut Dance – King Karudi and the Beautiful Ponmomi – At Ootacamund Market – A Trip to the Todas’ Mund – Milk and Betel at a Hindu Home – At the Botanical Garden – At the Seven-Kairns-Hill with Dr Griffith – Prehistoric Relics of India]

I gladly leave Madras and, happy to find myself safe and sound after breathing that air mixed with warm fog and germ-laden dust, steer my prow toward the Nilgiris, those enchanting mountains I have dreamed of for years and years, those blue mountains where I must find the Todas.

After a whole night spent in the railway car I see some lovely mountains at Salem, then endless palm trees and cultivated fields of rice, bananas, sugar, cotton, and capsicum peppers. Many villages ensconced among the coconut palms attest to the dense population and the riches of this land. Before Pothanur I could already see the Nilgiris in the distance and greeted them with anxious love. At Pothanur we leave the Bepur railway and board the branch line that will take us to Metapollium.

We are at the foot of the Nilgiris, or, as Breeks14 calls them, the Niligiris (from nila, blue, and giri, mountain). They call them this because in the distance they seem blue, or rather because in springtime the meadows on those mountains are covered with a thick carpet of blue flowers. The English today write Nilgiris or Nilgherris, and I leave it to the philologists to decide which of these forms is the correct one. What is beyond dispute is that the Nilgiris are set mid-tropics between 11° 10’ and 11° 32’ north latitude and 76° 59’ and 77° 31’ east longitude – and that they are an earthly paradise.

At Metapollium the railway ends, and one must ready the tonga15 for us, the ox-carts for baggage. I had telegraphed to have four tongas, whereas one would have sufficed, and an ox-cart, rather more economical than a tonga, would have accommodated all our baggage. Instead, the four tongas required some eight spare horses and an expense of two hundred rupees. An error that truly cost us dearly!

I was soon to undergo a second panic, when I saw descend on my trunks a whole population of coolies. They were so many that, even had I given each fifty cents, I would have had to spend quite a sum. Just imagine, that upon one medium-sized valise six coolies found the means to set their heads and arms. The stationmaster laughed at my dismay and assured me that I would not be ruined. In fact, the transportation of all the immense baggage cost no more than a rupee!

Forthwith I forgot my false alarm and the terrible bleeding made in my purse by four tongas, when in the multicoloured, Malaysian-type crowd milling about the station, I noticed a young black woman with long black curls and eyes of a blazing beauty. Certainly she was a Toda; she very much resembled the very beautiful portraits I had admired so often in Marshall’s work.16 I approached her smiling and said to her, in a questioning tone, ‘Toda?’ And she replied, ‘Toda!’ Alongside her, an old woman held a lance decorated with peacock feathers.

My anthropologist’s innards were afire with love, desire, frenzy. Here I was, at last, in wild India, meaning at home!

The colts of the tonga were tiny but ardent, never slowed their gallop, and at every moment were exchanged for others awaiting us along the road. They were running too quickly, those little horses, for I would have liked more time to admire the beauties of such fertile nature. First, there were fields of an extremely soft green rice and then forests of Areca, one of the loveliest palms in the world, shooting its emerald head heaven-ward with an agile trunk smooth as a column, then other palms (Borassus) and giant bamboo bushes, which at their base measured up to 500 millimetres in circumference and, bolt upright, propelled skyward for 20 and 30 metres, bending their spindly extremities in an arc, as though they were fishing rods. And from a single shrub sprang thirty, fifty, a hundred bamboo shoots, as from some pyrotechnic apparatus in the form of shooting rockets, which turned a single tuft into a forest. Now and then small silvery torrents and deep valleys with giant trees and leafless lianas that hung straight as ropes for 10 to 20 metres or wound in on themselves, coiled like a nest of vipers; and dangling below them, fruits and flowers of all colours and multicoloured little birds which looked fearlessly at us from their perfumed haunts, as though they were in a cage Nature had fashioned; and a warm scent of virgin forest that made my head spin. When the horses changed, I leaped down from my tonga with my botanist’s seed-receptacle and within a few minutes made a little booty of the loveliest plants for my friend Sommier.

At Coonoor, the Cutigliano of the Nilgiris,17 we changed carriages. Giant eucalyptuses and huge Australian acacias showed the invading but also reforming hand of the English: yet in that artificial flora I was happy to see the first flowering rhododendron, with its great bunches of red flowers, its ferruginous leaves, its trunk thick as that of our mediumsized chestnut tree.

As we approached Ootacamund (7,416 feet), the vegetation became entirely Australian, and the Eucalyptus and Acacia melanoxylon made up an enchanting garden. At 6:30 p.m. we arrived at Silk’s Hotel, where I took Room 2. I dined with four or five Englishmen and a lady with teeth so brilliantly white they were a poem unto themselves; then I warmed myself at a crackling little fire, which made me happier than I can say. Only a few hours before, I had sweated as I gazed out on sugar-cane fields, and now I was warming myself at a fire of Australian acacias.

Saturday, 7 January. I rise extremely early and climb the mountain, moving from one intoxication to another. This month of January, which for us others means snow, fog, stoves, and head colds, here signifies an emerald green on the land, a deep, transparent blue, a sapphire blue in the sky; an inebriating air of tepid coolness between land and sky. I walk amid woodland jasmine, flowering rhododendron, and the loveliest ferns. Every plant is a new friend to me, every bird that greets me a new acquaintance. From on high I see with real emotion, below, the first two Toda huts. I meet an Indian who, where I pass by, is breaking, to the right and left of him, a twig of the shrubs he has found. From the suspicious, fearful air with which he gazes at me, I think I can guess that with that operation he is defending himself from the evil eye I could cast upon him. Homo homini lupus18 and the evil eye are not just a Neapolitan, not even a Latin, invention. In that enchantment of nature, in that earthly paradise, man awakens a note of fear and suspicion. In my idle excursion I find a tiny, tranquil lake, designed by some fairy to hide her loves there. You reach it by immersing your foot in erpine and lichen velvets, and from a picturesque cliff a shrub of flowering rhododendron hangs over the water, which mirrors its bunch of pinks in the tranquil water. Beside that shrub a pure aloe, in bloom from its spiky nest, hurls skyward a direct flower-laden flame. The air is inebriating and raises my sensitivity to the highest pitches: it is so transparent, it seems you can touch the farthest mountains with your hands. The landscape is so rich and, in the vibrancy of the light, achieves hues so novel they keep me in a continual state of aesthetic intoxication.

Wednesday, 11 January. Cosa bella e mortal passa e non dura,19 and when the Eternal Father in his infinite justice finds a happy man on the face of the earth, he immediately declares him in flagrante delicto of a violation of the laws of nature: ‘Will be prosecuted!’20

And I was punished, in my excessively long walks and the excessively rapid change of climate, with a fierce lumbago, which for some days kept me fastened a sort of highchair, unable to photograph the Todas, to conduct research on skulls, to work. I must content myself with taking notes on the rare and valuable works I have borrowed from the Reading Room of Ootacamund, to which I have subscribed. […]

A Brief Account of the Todas and Their Neighbours – The Irulas –

The Kurumbas – The Kotas – The Badagas

To the Todas I shall be dedicating an illustrated monograph based on the portraits of them that I made from life, but permit me here to sketch some outlines of them which may serve to illustrate my voyage.

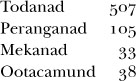

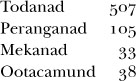

The Todas live in the Nilgiris, scattered over a vast mountainous territory surrounded by the Kotas, the Kurumbas, the Irulas, the Badagas,21 and many Hindus who settled in that country after the English made it the most important sanatorium22 of Southern India. According to the revised and corrected census of 15 November 1871, they number 683, distributed as follows:

The Todas are divided into two classes or castes, which cannot be joined in marriage, and are the Devalyal and the Tarserzhal. The first class claims to represent, more or less, the Brahmans, and consists of the Peiki Clan; the second is subdivided into the four categories of the Pekkan, Kuttan, Kenna, and Toda.

Their hardiness, their noble bearing, their very handsome features have won them comparison with the ancient Romans, but surely what has greatly contributed to this false analogy is simply the mantle, their only article of outer dress, with which they drape themselves, indeed, with singular majesty. There is also among them a quite Semitic type, some of whom could easily serve as excellent models for biblical patriarchs. They have thick, jet-black hair, flowing black beards, thick eyebrows, aquiline, often rabbinical, noses, large black eyes, fine mouths with very large lips, splendid teeth, chins neither receding nor over-prominent. The colour of their skin is like that of high-roasted chocolate, and I cannot concur with Shortt23 in calling it a dull copper hue.

The measuring of their heads has yielded to me the following results:

The Toda villages are called mund or mott and for the most part are made up of five distinct buildings, three serving as habitations, one as a dairy and temple, and another as a pen for the calves during the night. Their houses are made of bamboo, rattan, and sod, meshed together so tightly as to shut out the least ray of light, the least air bubble. When they have closed the tiny door from within with a real square cork, they are sealed up as though in a box. The houses are 10 feet high, 18 feet long, and 9 feet wide. The door is 32 inches high and 18 inches wide, so that one can enter only by slithering along the ground like a snake. Around the houses there is a stone wall with a narrow entrance, and a gap between house and wall 2 to 3 feet high, with a space of 13 feet by 10 feet. The facade is coloured with coats of red and black.

The inside of the house is 8 to 15 square feet, and only at the centre can a man stand up. It is divided into two parts, a lower one, where you find the fireplace, a few copper and bamboo vessels, the pestle for grinding the rice and other grains, and a hole in the ground, which is the mortar. The upper part, rising 2 feet above the lower, is the bed, and presents only some buffalo and deer hides: there, ten or twelve people of both sexes and of all ages sleep together.

The inhabitants of a mund are generally relatives and are considered one family. Each family may possess two or three mund in various regions of the mountain, to which they will periodically repair in order to graze their buffalo herds, which are almost their sole wealth, their treasure, the first object of their affections, if not their adoration.

The shepherd of the mund is also a priest. He milks the she-buffalo mornings and evenings during the months of monsoon, and in the other months only in the morning. The milk is kept in a dairy which only the priest, or pujari, may enter.

Every family has a recognized head, in the case of whose death the older son almost always succeeds him.

The Todas are a pastoral people who live only on buffalo milk, honey, and gudu, or a grain tribute paid to them by the Badaga and Kota peoples as rent for land, which is considered the Todas’ ancient and legitimate property. They disdain work, are proud, and laugh often and heartily even at the Europeans.

Inheritance is divided equally among the sons; the house goes to the younger son, whose obligation it is to provide for the sustenance of the women of the house.

The Todas, up until recent years, were polyandrous, but now, with infanticide of their newborn girls strictly forbidden by the English, they are becoming monogamous, and I have known some among them to have confessed to being polygamous.

The women embroider red and turquoise into their white mantles, which are made of cotton they buy from their neighbours, they tend to the kitchen and fetch the water. The men take care of the firewood and raise the livestock.

Here are some names the Todas take:

Men’s Names

Kevi: sacred bell of the buffalo

Pernal: great man

Narikut: jackal’s son

Ponkut: son of gold

Tshinkut: idem

Padrithzh: with God who dwells on the mountain

Kedalven: man of the funeral

Alven: man

Beltaven: like silver

Kirneli: small on

Women’s Names

Kathaveli: silver coin

Darzthinir: jewel splinter

Tshinab: golden

Berzth: ?[sic]

Depbili: silver ring

Piltimuruga: white earring

Piltzaras: white ring

Takem: doctor (because she was cured by a European doctor, shortly after birth)

Pondshilkammi: little golden bell worn at the ankle

The Todas dress in a large white cloak or mantle, and go about barefoot and bareheaded. Only recently have some adopted the Hindu turban.

The women wear huge silver earrings, extremely heavy bronze bracelets, and other lighter, more ornate silver ones, and wear rings in various shapes. They tattoo the neck and arms in blue, simple, elegant designs.

They burn their dead like the Hindus, sacrificing buffaloes during the funeral they call the green one, and they let their neighbours the Kotas eat the flesh of the sacrificed animals. They hold a second funeral, which they call the dry one, and which once they would always solemnize two or three months after the first. Today, however, to spare the buffaloes that must be killed on that occasion, they wait at least a year and thus mourn many dead at one time.

For the dry funeral they save fragments of the cremated skull and a tuft of hair and offer these once more to the pyre, after dousing them in the blood of the slaughtered buffaloes. On this occasion, various objects which belonged to the deceased are also burned, together with a flute or a kind of bow and arrow and another sort of buffalo horns. These are sacred symbols and nothing more, since the Todas no longer use bows and arrows and have no weapon but a large, high staff with which they kill the buffaloes in their two funerals.

In the dry funeral they also perform a sacred dance, in which anywhere from twenty to fifty men take part.

It is difficult to gain an accurate sense of the religion of the Todas. They recognize the existence of various divinities, and perhaps their Usuru Swami is also a supreme deity. They have neither idolatry nor fetishism, and offer their gods neither human nor animal sacrifices. They believe in an afterlife, but have no clear ideas about it, unsure if it is only the soul that passes beyond death or whether the body also accompanies it.

The Todas’ place of origin is still uncertain. Marshall, who lived among them a long time and studied them with loving exactitude, thinks it fairly likely that their ancestors lived in the low hills between the Canarese and Tamil districts, in the direction of Hasanur, and that they emigrated from there, breaking up into two different groups. One of them headed northward, to Kollegal, and the other settled in the Nilgiris. Metz25 says they came from Kaligal, and they themselves, when questioned on their origin, reply that they have always lived in the same country. What is certain is that they have always had a relation with the west coast of India, as the ornaments of their women’s face-powdering prove.

The first reports about the Todas, according to Breeks, are found in the journal of the archbishop of Goa, Aleixo de Menezes (Coimbra, 1606). At the Synod of Udiamparur in the State of Chichin held by the same archbishop in 1599, you have information about a Christian people that inhabited an area called Tadamala that had lost its religious beliefs; so it was decided to send certain priests to visit it, including Iacomo Ferreiro. In the account he left of his voyage, he describes the Todas, but says he has found no record among them of Christian faith. They said their fathers had come from the East.

The Todas are discussed also in the Viaggio alle Indie Orientali by Padre F. Vincenzo Maria di Santa Caterina da Siena, procurer-general of the Barefoot Carmelites (Rome, 1672; Venice, 1683). This father made his voyage in 1657, but gathered notes on the coast. This is what he says: ‘The Todri [sic], a small tribe of a rather light-skinned [sic] people, live on the mountains behind Ponane, in the Kingdom of Zamorin, and pray to the buffaloes on which they live. They select the oldest cows and hang on them a little bell, which suffices as a means of adoring them. They allow the buffaloes to wander at will and also to graze in the fields, and everyone considers himself fortunate to eat something that belongs to them. Although the buffaloes are often killed by tigers, the people do not cease on that account to adore them.’

All ethnologists classify the Todas among the Dravidian races, but let me repeat what I have said elsewhere, that we must throw out the concept of a Dravidian race. Dravidian languages exist, but not races, and the philological criterion, as in many other cases, adopted as the sole classificatory criterion for peoples, has led to the gravest errors. The Todas, of Semitic type, speak Dravidian languages, as do the Kotas, as Aryan as the finest European, the athletic coolies of Madras, and the Malaysian-type people of the Malabar coast. For this reason, must we say that men this diverse in skull formation, physiognomy, indeed, all their anatomical characteristics belong to a single race? By that logic one would have to assert that all humans on the face of the earth belong to one race and are but varieties of Linnaeus’s Homo sapiens. Bold as this assertion will sound, for me there are no distinct, well-defined races such as the Dravidians, just as Semites and Aryans do not exist, and it would be wise to erase these distinctions, which in their philological baptism suggest an ancient error, one imposed with the full force of an indisputable, irrevocable tradition on anthropology and ethnology. […]

And these Todas, so splendid, so hale, so happy, what will become of them? What will become of their neighbours? They will vanish, intermingling with races close to them.

Their individuality pales by the day. With their infanticide hindered, and their prosperity increased, they will gradually become monogamous, perhaps also polygamous. They already wear the turban: soon they will be finding trousers and jacket more comfortable. Perhaps they will also become Christians: then they will cross-breed with Hindus, with Muslims, with Eurasians, and their blood will be lost in the great ocean of the human family.

A traveller visiting the south of India two or three centuries hence will glimpse, here and there, some Toda physiognomy, the ancestral glimmer of a lost, and quite ancient, form, and will say, ‘Look, here is a Toda, like one in those photographs by Breeks, Marshall, Mantegazza.’ Perhaps, too, nothing of these black patriarchs I have so lovingly studied will appear again. In the ocean all drops look alike, whether they have come from the glaciers of the Faulhorn or Kanchanyanga, from the forests of Cotopaxi or New Zealand. If all those drops were to tell their stories, they would give us the greatest poem the world would ever know, they would give us the history of the living and the dead, from the tears of a dying man to the dewdrop gathered at dawn from amid the rose-petals: but all those drops sunk into the great seabed fall asleep or murmur a single language, telling us that from the microcosm of an atom to the macrocosm of the universe, existences and forces, actions and reactions war and are reconciled, recuperate the small in the great, preparing for the morrow’s struggles in a moment of respite, while human shades flit across the horizon, like fog dissipated by the rising sun.

[Darjeeling –] The Kanchanyanga – [The Market and the Purchase of a Chonga –] The Puhari – A Trip to the Bhootea Bustee – [My Portrait among the Clouds –] The Himalaya and the Alps – A Ride to Runjit – [A Hand-to-Hand Fight with a Bootia Girl – Master Partridge – My Occupations in Sikkim –] The Wandering Merchants

[…] 19 February, 7:45 a.m. For a half-hour I have been on a hillock behind my bungalow, seated upon a gleaming mica schist. The ground is silvered with hoarfrost, and the grass bare. Facing me is Kanchanyanga,26 which I am seeing for the first time. It is the second, or we might say the foremost, mountain in the world, since Everest is only somewhat higher. It is the finest thing in creation; I would not place a starry sky or stormy sea beside it; the sky we see from the time we are babes, and the sea in its fury is always so convulsive. Here, though, I have before me force without struggle, grandeur without pride.

I saw it at 6:45, on climbing over the edge of a hillock. Behold it, calm, serene, stretching east to west its boundless arms bristling with silver tips and glaciers. Beneath the snows, light, fleecy clouds knit for it a sort of cravat, farther down they weave it a garment, then its whole body plunges into a sea of thick, shapeless clouds. Who can ever count the peaks that the great giant Himalaya commands? To the right they stand out, high and hardy, then lower and lower fade out in a fine, jagged line.

I am dumbfounded, and even if I were not alone would still be speechless. I feel too small in the face of this overlarge scenery. I look for something more like me in its smallness.

Behind me a small Anglican church sleeps calmly in the peace of faith: about me all is silence, and even India’s eternal ravens, which for months now have deafened me with their clamour, have either flown far off or fallen silent.

I rested my eyes on the little church, yet my eyes strayed back to Kanchanyanga, spellbound by that colossus. Just look at him there, he seems mirrored in the ocean of clouds at his feet, and gazes out with pleasure to come off so big, so handsome.

Yes, he is king of all those clouds hugging and squeezing him everywhere, he is their lover. They have just left him practically uncovered; yet they seem to yearn to kiss him again, and run back, collide, dart over his brow, and every so often veil him, hiding him from me. But here comes a more powerful morning breeze, crashing down all those petulant clouds, so that Kanchanyanga again appears quite naked, yet chaste in all his nudity.

My heart is pounding, as I wish I were a poet, a lyric poet at that, to sing the beauties of this giant. Nothing speaks inside me but a hymn. The mountain is silver, diamond too, the flower of stones; it is inorganic nature’s feast, its hymn. And yet, when the clouds gird him and closely cleave to him, I seem to see a little bud of musk rose made for a garden of the heavens and a God of flowers. I catch myself lapsing into the seventeenth century, as the language of men, so inspired before the colossus of Himalaya, turns grotesque. I am a child standing on tiptoe to kiss a giant.

20 February, 6 a.m. This morning the clouds are unwilling to quit the embrace of their giant. In vain does the sun rise behind me at this moment, to give its customary morning kiss to Kanchanyanga. The clouds refuse to uncover him. Some, very, very gently, tear themselves away, into vaporous flakes, rise to fall again to kiss the brow of their lover; other, pinker ones encircle his neck, his breast, all over. And he, motionless, consents to their love and admiration.

It seems proper to me to be witnessing a scene of creation, to make out the face in this chaos of clouds that have a form, yet still find no form in them; I seem to be seeing ancient protoplasm, reduced to an amorphous vapour; seem to be witnessing some occult, mysterious fermentation which moulds and organizes the first peak of Kanchanyanga, the first land of a world to come. No, I am not deceiving myself, what I have before me is Genesis in action. Here is the ocean of protoplasm, here, down in the deep chasm of Himalaya’s valleys, is a borderless grey air on a gradual ascendant; the soft, vaporous grey rises, rounds into swan plumage, wool fleece, cotton flakes, sketching out the first twilights of form.

But behold, this ash-grey ocean is torn at some point, and, like a cliff in the sea, an unimaginably green hillock rises up; on it sits a small human habitation …

21 February. I see you a third time, O Kanchanyanga. You are still beautiful, ever beautiful. You are virgin, O Kanchanyanga – you alone are that. Everywhere that the sun has kissed the earth, a hundred, a thousand creatures have been born, be they dwarf birches or giant well-ingtonias, wart viruses invisible to the naked eye or religious, thousand-armed fig trees, each tree a forest unto itself, bacteria beside which a dust mote is a mountain, or elephants, which are mountains of flesh; deep within the caves or the sea’s chasms, wherever the air has touched the earth, the creatures swarm and crowd.

Our planet is one great marriage bed of easy, tireless loves.

You alone are virgin, O Kanchanyanga, your cliffs are not eaten by lichen nor dressed in moss; over you neither fly nor butterfly’s wing has ever beaten; nor has bird’s voice ever sung. Your snow is still pure of the contact of human feet, that arrogant tread that has touched and sullied everything.

Yet you are too beautiful, O Kanchanyanga, not to love! You make love with the light that intoxicates you as it dresses you in silvers and purples; you make love with the clouds that caress your calm brow; you make love with the sky’s infinite spaces, within which you plunge, with the daring of the strong.

Your loves are eternal, as unliving things are eternal. You are the inorganic world’s feast, its hymn. The plant world has the wellingtonia and the baobab, the animal world the lion and the bird of paradise; the mineral world the Kanchanyanga, Illimani, Mont Blanc. You are the wealth, the beauty, the jewel of mountains. You alone manage to touch the sky so closely you can squeeze it with your mighty arms, so that you can conquer its boundless fields, you are so large you win admiration, and so close to us you win also our love; the love of us poor creatures of a day, who have fixed boundaries and duties levied upon on every sense, our every desire, our every love.

22 February. Ah, today you are naked, my Kanchanyanga; you are naked, yet chaste as a statue by Phidias. Even the most modest ladies allow the companion of their loves to contemplate their naked beauty a moment.

Yet behold how even today I could not truly call you mine, since on your shoulders you wear the sheerest opal-coloured veil, which does not conceal you but multiplies your infinite beauty. It is the roseate flesh of a young girl seen and not seen through a gauze veil.

You are naked and you are beautiful, nor have you need of hands to hide any defect. The most beautiful things do not reach the highest peaks of ecstasy unless they are beautiful from the tips of their feet to the last recalcitrant curl on their head. You are large without being baroque, and the ornaments of your profile are worthy of your immense beauty. Nature, having exalted you to the skies in a surge of giant fecundity, has patiently chiselled you with her hand from head to toe. With my enamoured gaze I follow your silvery outline and count ten, twelve larger peaks, each different from the other and all bound up with other, lesser jagged outlines, petulant as the marble breast of a maiden or as finely serrated as fern leaves. To left and right you stretch the curtain of a hundred peaks, give your hand to Nepal and Bhutan and hide China from my eyes. If a railway could lead me to you, I would touch you in a half-hour of travel, but neither rail nor telegraph wires have yet tamed or conquered you. You stand there like a milestone between the Mongol and Aryan worlds; a giant godfather of two of the greatest civilizations.

And how many tiny new beauties does my eye not discover in your sturdy limbs, how many shadows and penumbrae of polished, blonde silver. You have the full cool, graceful range of white, the purest, most chaste, most virginal of colours. And between one white and another you place black shadows of granite to let the splendours of your silvers stand out all the more dazzlingly. You are a colossus drafted by Michelangelo and chiselled by Cellini. The measureless grandeur of your slopes deprives you of none of the graces of a Grecian statue.

So it often happens that one must also admire in some superb Roman beauty dimples of the face and the unsurpassed loveliness of the pubescent lip – lesser beauties of a divine beauty. So too on the brow of an Arab horse black as night, a miracle of agility, elegance, and strength, you see Nature, insatiable in its aesthetic fecundity, whimsically painting a small silver star.

After great things, small ones; after lyrical emotion, which carries you aloft, the pedestrian walk that takes you along the modest paths of daily life. Thus is man; thus complete life, which rests upon change of sensations, which multiplies the bread and fish of our poor, brief life with the miracle of skilful alternatives.

In fidelity to the plan of my book, I am transcribing other notes from my notebook. […]

Monday, 20 February.27 For many long hours, and with great sensual pleasure, I warmed myself by the blaze of my small fireplace. The notion that I’m in India delights me, the blaze cheers me, and I am just a bit proud that the wood now warming me is magnolia and rhododendron.

Before my meal I step out for a walk alone in the hills. In vain do I search in order to find some specimen of a flowering plant for my friend Sommier, but above the ridge of a higher hill, amid the low shrubs, I discover a place sacred to the Buddhist cult. There are clots of blood, fleeces of wool, and small cloth rags of various colours hanging from the branches of the trees and the nearby shrubs.

Later, on other occasions, I saw the same things in other places, and beside the blood, which came from small animals, I also saw chicken feathers. I have never been able to witness the actual sacrifice.

The bath water is brought to me each day by a poor Indian, lame and ugly as sin. He is no cleaner than his brethren in Sikkim; indeed, if such were possible, he is even dirtier than they. And yet he lives, in two senses, by water.

I have seen a few others similar to him. They do not have the Mongolian face, and tell me they are pahari or puhari.28 They are brown but not yellow, have neither slanted eyes nor prominent cheeks; they have flowing black hair, beards fuller than the Sikkimese. They assure me they were born in Nepal and in the Kshatriya29 caste. If it is true, then they must be the caricature of Mars, for they have nothing bellicose about them, and I think they have never waged any war but against the people of Pediculus,30 by whom they have been invaded, like all their brethren in India. Should you wish to do anthropology in these countries, and even more, should you wish to take photographs in them, for pity’s sake do not forget to bring phenic acid; otherwise you will threaten to populate Europe with some new species of the genus Pediculus, sowing great confusion among the entomologists. […]

21 February. At last I have been able to see the Buddhist temple at Darjeeling. It is reached by a picturesque road winding on the mountain slope that sinks and rises and dips to make way for a streamlet framed by trees and grassy clods of earth that stretches along the edge of the chasms and widens out before certain Bhutanese31 houses that look like swallows’ nests set between sky and earth.

Along the road you find a whole Bhutanese village, a village without streets, because you find no more than two or three houses at the same level; instead they are scattered, or rather, flung helter-skelter, over rock clefts and in the small inlets of the mountain. Men, sleepy-eyed and dishevelled, emerge from them in droves; they seem permanently suspended between the drowsiness of weary lust and narcotic hallucinations, but the Bhutanese girls are much better looking, with cheeks in a deep pink that contrasts with the yellow undertone and their slanted little eyes and their whimsical little noses that give them an air of charming pertness. That dark pinkishness greatly preoccupied me for the length of my stay in Sikkim, because it is a rare colour in the Mongolian races, and at times it seemed I should have to consider it artificial. They blush, however, at your mere glance at them, and this is certainly a natural reddening, contrasting with the free mores of their polyandrous life.

How cheerful those lovely lasses were as they chattered! I saw them upon an esplanade in front of one of their huts, leaping, dancing, and running about with bundles of lit straw which they threw at one another over their shoulders, laughing scornfully with enviable naivety. They offered us their jewellery, their bracelets; yet they always asked permission of their mothers, and lovingly discussed among their family how best to fleece us.

Further on below the Bhutanese village you find the tomb of a lama, almost impudently white, in an extremely simple architectural style of the sort often seen reproduced in travel works. Finally you reach the temple, where the ugliest thing is the church, damnably clashing with the quite splendid panorama of the deep valley, the nearby mountains, the distant giant of Himalaya. A broad fence stands before the temple like the small piazza of one of our small mountain churches, then plunges over the deep and narrow valley. Many quite tall bamboos bear veritable bed-sheets of paper on which are written Tibetan prayers.

The temple is a small lime and brick house with a covered atrium decorated in wood and painted board. On the left, beneath the tiny porch, a lama, seated on the ground, with a rather unscrubbed and, worse still, moronic face, has before him a large book in which he makes a show of reading while constantly spinning with one hand a huge prayer machine, on which are inscribed the customary Tibetan prayers. The large spinning holy machine strikes two bells, small and large, that clang in different tones. On both sides of the atrium, or doorway if you will, you see arrayed two sets of other, smaller prayer wheels, covered in painted and gilt paper. Three other lamas crouching below these ridiculous playthings sing out their nasal psalms.

The famous prayer wheel, or ‘coffee roasting machine,’32 is one of the greatest curiosities of Buddhist worship, and no traveller, however miserly he may be, ever visits Sikkim without taking home one of these odd little machines, which are copper for the poor and silver for the rich, with a cover and a metal ball that helps it to spin, and upon which are almost invariably carved the prophetic words Hom mani padmi hoong,33 Praise be to the lotus flower, praise be to the jewel! When the little machine has a cover, you can have another prayer, any prayer, written on the paper. The devout Buddhist, walking, riding, idling, continually spins the little machine and thinks of quite other things. Meanwhile, however, he is satisfying a religious obligation, and the Eternal Father is satisfied by this mechanical prayer. They look like large-scale mills over which prayers fall like water.

I entered into the temple anything but disposed to worship, and saw, on the ground on both sides, seated in Turkish fashion, some twenty lamas singing through their noses before huge books that a young cleric was perfuming with a sort of burned incense as he passed from one lama to the next. Behind them, little boys were crouching, and in a corner of the church I also espied a large vessel of murva.34 People more lanky, stupid-looking, and abject would be hard to imagine, and one lama, seated apart in the middle of the church, spinning a silver prayer-mill with monotonous regularity, held out his hand and spoke perhaps the one English word he knew: Money, money, money. I felt an unspeakable disgust, a deep shame to be a human being and to see this puerile and debased business dignified with the name of religion.

I bade my interpreter tell the mill-wielding priest that I would give money35 after I had visited the temple, and would pay them well provided they sang well. As though by a spell, scarcely was my thought translated into their language than these twenty singers raised the pitches of their chant, though still reaching them through the nose.

No church more closely resembles one of our own than a Buddhist temple. An inner altar at the farthest end with three gilt gods, entirely decorated with flowers, vases, small vessels with offerings of rice and perfumed little candles burning slowly. At the foot of the altar, the musical instruments of the Buddhist cult, from huge bronze trumpets to a humble shell.

Seeing a basket holding an immense number of little brass vessels for the offerings, I asked an officiating cleric for one, offering of course to pay him for it, and as much as he wanted. The good little priest was perhaps the only one among those slyboots, drunk on music and who knows what preternatural lusts, who truly believed in the religion of which he was minister. He took deep offence at my proposal and firmly refused to sell me one of the little vessels. I begged, implored, but all in vain; then, making an accomplice of one of my travel companions, I stole from him the little vessel he would not sell me. The museum directors, the collectors, numismatists, etc. all are more or less thieves, and now I was too; except that I stole badly, for my cleric exposed me as a sacrilegious thief to the singer-priests, who rose from their places and encircled me. Their imbecilic but malicious faces did not frighten me in the least, however; and I, adding a lie to a theft, denied stealing it and dared the over-zealous little cleric to prove my theft. He gesticulated and shouted like one possessed, saying there were x many little vessels, all of which he would count out in front of everyone until he found one fewer, which would certainly be in my pockets. That diabolical lama in the making had an eagle’s eye!

Except that a European from Monza neither could nor should let himself be defeated by a fanatical little priest from Darjeeling; and having called to my accomplice, while the cleric was deliberately distracted by my friends without realizing it, I set the little vessel back among the others. It was then, dear reader, that, sure of my slightly posthumous but nonetheless genuine innocence, I crossed my arms over my chest, defying my adversary to prove the theft!

He counted, recounted, furrowing his brow to hone his mathematical skill, and had to conclude, with the greatest confusion, that the little vessels were x many and just as many as there should be, and that he had imagined a non-existent thief.

I laughed to myself, but laughed even harder when, on leaving the temple, I saw a fat old lama grin sarcastically and with a wink approach me, and put my hand in his pocket; in it I found the little sacred vessel I had shortly before tried to plunder. I in turn gave an Attic grin and slipped a rupee into the hand of that good lama, who had corrected the over-zeal of the neophyte cleric. The latter, the next day, putting in order the temple’s implements and recounting the little vessels, must have found one fewer and slapped his brow, telling himself who knows how many times he was a befuddled idiot. But I was not the thief!

Those lamas of Darjeeling really are sly! I had tried to buy one of the long bronze slide trumpets which I had seen at the foot of the altar, but however high I kept raising my offering price, all the priests rejected the sacrilegious proposal with horror. This indignation too was false! The next day around sunset, a messenger of the lamas came to my house and my room with a mysterious bundle and laid out before me two of those sacred trumpets. One is now in the hands of the lawyer Michela, the other is an outstanding piece in my museum in Florence.

As I left that temple with its filthy lamas, I could see two of them with large red mitres who, standing together by the church fence, blew their shell trumpets, calling the faithful to prayer. Their notes were echoing mysteriously through the deep valley, and the distant echo repeated the notes with a mocking air.

And I, homeward bound, thought sad thoughts.

Ramdas Sen was quite right to say of Buddhism in his lecture in Calcutta on 19 September 1870, ‘Unfortunately the religion of Buddha no longer finds itself in the state of purity it enjoyed in the days of Sakya Muni.’

The ethical part of the Buddhist religion is genuinely sublime. The Buddha’s Dhammapada, or ‘Way of Virtue,’ is a true brother of the Gospel.36

Fergusson also finds many analogies in the histories of Christianity and Buddhism: ‘Three hundred years after Buddha, Asoka did for Buddhism what Constantine did for Christianity. He adopted it, made it the religion of State, actively cooperating in its propagation. Six centuries after Buddha, Nagarjuna and Kannka did for the Oriental religion what Saint Benedict and Gregory the Great did for the Occidental religion. In the XVIth century we have the Reformation and sixteen centuries after Buddha we have in Sankara Acharjya the Luther of India.’37

If Buddha were to rise up from his tomb, he would not recognize as his disciples the stupid priests of Sikkim; just as the Christ would have to chase from the Temple those who call themselves his followers.

Why is there this conflict?

For many reasons, but this one above all: that religion is the least progressive of human institutions, because its dogmatic form immobilizes it and its indisputability and sanctity make even the least change abhorrent.

From this derives the fact that while arts, sciences, letters advance with a certain concord and considerable parallelism, religion lags behind and no longer responds to the needs, sentiments, or criticism of today. For this reason it can agree only with the tastes of the lowest strata of human society, that is, with those who, straggling behind through their lack of culture and deficiency of thought, find themselves differing less with ancient religion since they belong to a time whose sun has set. And the priests, to make matters worse, speculate in the industry of simony.

The high and intelligent classes no longer side with religion, and the indifferent follow its rituals by tradition but without faith or enthusiasm.

All this does not prove the uselessness of religions, but rather the need for those to be reformed and to follow the destined course of our thought, as happens with every other human institution. There may be, nay, there have been, still are, and always will be men who do not feel the need for a religion, yet the family of man will always be religious, because the hope in a better world, or at least in one different from this one, because the need to believe in things unseen, untouchable, because the love of the mystical are all human and indisputable elements; yet anyone who would redeem religion must be ready to reform it when it no longer responds to the moral and intellectual climate of an era and a people. It is better to bury a glorious corpse than to leave it standing up lifeless, while the ghosts of simony and the drones of superstition devour every shred of its flesh, infecting the air, spreading stench and corruption all about them.

Men have forever walked on high and men will always love ascending to the heights of the ideal world. First, they moved about on their feet, then on the backs of horses and elephants, then on steamers, and, who knows, someday perhaps they will go flying about.

Religion too bears us aloft, and one should not, must not suppress it, but for the pedestrian religion of the savage or the religion borne upon the backs of great thinkers, one must spread the wings of all poetries, all the hopes, all the ideals of the family of man.

21 February. Yesterday for the first time I saw a surprising spectacle. I was roaming over these charming mountains when all at once, casting my gaze toward the valley, I saw my head reproduced on a giant scale over a facing cloud-bank: and the sun, at my back, was surrounding my fantastic image with a halo of shining, iridescent rays. For many minutes I was stunned; then, like a boy, I took to moving my head and arms, enchanted to see my portrait drawn in giant proportions by the sun over the clouds of Himalaya.

I really am in an enchanted region, and Hooker38 may not be exaggerating in calling Darjeeling the most beautiful spot on the planet. I too have toured a fair share of the world, and of all I have seen of Europe, Asia, Africa, and America, I would not hesitate to say that coastal Rio de Janeiro and landlocked Darjeeling are the two natural settings I have most admired.

Here, truly, I find all the forms of the beautiful – the grand, boundless beautiful that leaves you humbled and small, like a grain of sand amid the deserts of the Sahara, and the graceful beautiful that you can fondle with your hands and almost kiss with your lips. Before your insatiable eyes rises the greatest mountain chain the planet can boast; and between you and Himalaya lies an ocean of mountains, hillocks, hills; ever green forests of magnolias, rhododendrons, and conifers, with villages scattered through the greenery like little swallows’ nests, and above all that world of stones and greenery, another ocean of sky and clouds and fogs ever in motion, now about to be chased after, now lying still on the giant basins of the valleys. Nowhere have I seen such restless, turbulent clouds; they move from vale to vale, plunge from a mountain gorge, as though an invisible hand wanted to pour them into and completely fill the valleys below. Then, all of a sudden, a capricious wind seizes on some winged fleece that flies and flies, and to your great envy it rushes off on a junket to Tibet, and a few moment later, seeing that all’s well in China, returns to you in India, only to pour itself into the infinite lake of other, sister clouds.

How happily the sun sports, how it amuses itself amid that ocean of clouds, how the moon revels on high amid those thousand shadows and penumbrae of the little dales, the inlets, the deep clefts. The most colossal trees seem from afar to be the silken down on a baby’s face, and the tree ferns jutting far off the edge of a precipice seem like those ‘flaws,’ those cherished beauty marks that prodigal, gallant Nature sometimes plants on the face of our loveliest ladies.

One sometimes feels weary from too much admiration, one feels the need to take refuge in the woods, to sit at the feet of a magnolia with one’s eyes shut. Today I have hidden in a forest and for a long time have remained seated on the dry leaves, savouring the voluptuousness of a long silence. When my restless hand moved to rummage in that bed of leaves, I found beneath them a carpet of gilt soft ferns and of bronze-coloured true ferns delicate as Brussels lace; and amid the ferns I picked a white violet with blue stripes. It was the first flower that spring let bloom on the first steps of Himalaya.

Which are more beautiful, the Alps or Himalaya?

If love of country does not befog my judgment, I would say that the Alps are not only more beautiful than all the mountains of Europe but also than the Cordilleras of the Andes and Himalaya. Nature has fashioned them with a richer aesthetic, caressed them with greater coquetry of profiles, outlines, and colours. They are the worthy frame of that gem of our planet that is Italy: they open the gates to the earthly paradise of art. Himalaya is grander, more severe; it is the curtain worthy of parting the two most populous families of man, the Mongol and the Aryan, the Chinese world and the Indo-European.

25 February. Having had, through no fault of my own, to abandon a voyage to Tumlong, the capital of independent Sikkim, I wanted at least to say that I had been to China, or in some tributary state to it, so with my companions and other young Russians and Frenchmen I made an excursion on the River Runjit. On the descent they all took the route on foot; I being older, lazier, and, above all, surer of the ability of my Tibetan pooni, made the whole way on horseback. And no beauty he was, my pooni! A dirty bay, completely dishevelled, gaunt, he seemed made more of wood than flesh. He did not neigh, did not shake his ugly head, did not impatiently paw the ground; yet what assurance in the way he slipped through those abysses, what an eye, what sureness of step, what indefatigability! He never stumbled, never showed the least tiredness, never bent his back. Although a mere quadruped, he was much more likeable than the green biped who accompanied me as my coolie. He was taciturn, sullen, unpleasant, and you can’t imagine the ugly face he made to me when I, with the kindest smile in the world, offered him one of my sandwiches. It contained beef, and he was a thrice-orthodox Hindu!

But then all our coolies were quite unpleasant. Another, without warning me, threw over into the valley a splendid bamboo knot which I had bought along the road for the mere pocket-change of two annas. It was more than a half-metre in circumference, and I had planned, once back in Florence, to make from it the most beautiful and unusual cup in the world. And I had even promised him a one-rupee tip. But he was a coolie, not a porter, and could not lower himself to carry a bamboo for me. I had engaged a third man to carry for me a narguileh39 of bamboo and terra cotta that I had bought from a travelling merchant; but he threw the pipe away, snorting and disdainful. I had offended him: he was no porter. I begged him, implored him, promised him a suitable tip, but he would not yield, until I myself had put into my pocket a piece of the narguileh, indeed the heaviest. Just as well: his honour was saved, and my pipe in safe keeping.

These, however, were but insignificant stings amid the magnificent world surrounding me on every side. The deep green tea plantations alternated at every turn with the virgin forests, where the most enormous trees bore hundreds and thousands of orchids on their boughs. The tree ferns, in their slender elegance, raised their heads over the edges of the abyss, reunited in little families of three, four, and five individuals. The flora grew richer the farther one descended into the deepest, hottest valley, and the ferns, in a hundred different species, revealed to me all the most delicate, aristocratic, and multicoloured forms in their exquisitely beautiful family.

After traversing ten miles among the charms of a landscape unique in the world, we arrived at the Runjit, a river crossed over by a very unsafe and shaky wooden bridge. On foot I wanted to see where this river joins the Teesta. The latter has cold, sea-coloured water, whereas the Runjit has dark green water, bright as emerald, and warmer. The two waters flow together a long way, without fusing, until, tamed by long contact, they embrace, merging into a single wave.

The Runjit forms the border between independent Sikkim and Bhutan. I crossed it in a giant canoe dug out of a single tree-trunk. One could not even consider crossing it on the rattan suspension bridge, so worn not even a monkey could safely use it. I was unable then to experience the feeling of motion these most ingenious bridges give, slung like hammocks between sky and water and on which only one person at a time can cross. At the bottom of this water many motionless trouts were visible.

Beyond the river I came upon a very poor village, from whose wooden houses were emerging dirty, dishevelled, ragged people. They spoke of being Magìa, but who knows what they meant by this word. To me they looked like Limbù.40

They were extremely greedy for money, and for that money they were willing to show me their hands, and sold me jewels and a sacred trumpet made from a human femur. A girl fled in fear into her hut and shut herself in there because I had asked to see her necklace with the goal of buying it. I gave another pretty girl a box of wax matches decorated with a small mirror, which made her beam ecstatically before the object, so new and curious. Some men wanted to grab it away from her, but I made them give it back to her, for which she showed me great gratitude. It was impossible to persuade a fisherman to sell me a splendid sort of net that I have seen used in several places across India, most often on the banks of the Ganges. He replied to me that without that net he could not eat and so would die of hunger. I kept piling up the number of rupees in my hand and, jiggling them about fondly, answered him (always through an interpreter) that with those fine silver coins he could have made himself another net and bought other things too. He stared at the rupees, looked at the net; yet I kept my money and he his net.

An old drunk emerged from a hut, but no one except some boys laughed at him. On the contrary, everyone else was visibly ashamed, and happy only when they had him removed from my sight.

I crossed back over the river in the same pirogue; but when I wanted to try to play my trumpet made from a human femur, I saw the most unfathomable dismay come over the face of my oarsmen, and a Lepcha41 flung himself at my knees, imploring me not to play, since if I did, we would all be drowned.

I dared not continue, since the distress written across that poor Lepcha was too harrowing, and I stepped back down onto the right bank of the river, re-entering English India, where a curious incident awaited me that threatened to become an outright accident. A native was scooping some water from the river with a lovely cup made of tree-bark and with a graceful handle. I had never seen anything like it before and wanted to have it for my museum. Bargaining, I got it for eight annas.

I was proud of this acquisition and went about showing it at a distance to my companions, when suddenly out of a hut came a young, not unattractive woman, who flung herself upon me and, without leaving me a second in which to defend myself, seized the precious cup from me, screaming and hurling who knows what curses against me. I called out for my interpreter and companions, but no one heard me; and I grappled with this strapping woman, who, stronger than me, kept the cup tightly tucked in an armpit. Seeing, however, that it was not very safe there, she moved it between her thighs, which I could approach at my peril, thus paying for my decency with my property rights. I was still trying to resolve the problem for the best when I found myself surrounded by many Indians armed with bows, sticks, and their wrath, who closed ranks about me with threatening cries.

Thereupon my travel companions became aware of my struggle and, laughing, ran to my aid, thinking, however, that I had wanted something quite other from this young woman than my cup. For a few moments I was considered victim to an access of erotic fury. A young Russian, however, correctly grasped the situation and helped me wrest the cup back from the woman. I then gave her to understand, through the interpreter, that the cup was mine, since I had bought it from an Indian man, and having suddenly seen him among the many men who had rushed toward me, I pointed him out to the young shrew. It turned out that this man was her husband, and without consulting her had sold an object that not only was hers but was cherished by her.

Ope, ye heavens! Never shall I forget the look of shame and compunction on the face of that poor husband. She punched him with her fists and scolded him with words I could not understand but that must have been extremely harsh, given the effect they produced. He was silent, visibly repentant, and implored me with his gaze to return the cup to the aggrieved woman without whose permission he had sold it. The bad thing was that he did not want to return the eight annas to me; and I wanted either the cup or my money. I doubled, tripled the price; but there was no way of obtaining the cup. I took back the money, and the woman retrieved the cup, which, without the intervention of the courteous Russian and the explanations and translations of my interpreter, might well have landed me in a very bad position.

Our meal was in the entryway of a small mud house, which also served as a shop, and I ate with a poet’s appetite, devouring chocolate, bread, a sandwich, oranges. Some itinerant merchants were watching us, sternly silent. Their natures did not correspond with ours. And yet I felt a keen need to make contact with those men.

A sprightly, cheerful child was grazing some kid goats close by us; and with some effort I made friends with him, by gifts of oranges and paise. He put out his hand, then brought it reverently to his brow and saluted me, with a beautiful smile. He, at least, was a brother to me.

While we sweated on the bank of the Runjit, in Darjeeling it was snowing heavily, and upon our return the snow was still whitening the very tops of the hills of the capital of English Sikkim.

The Himalayan chain was a dazzling, adamantine white on the blue horizon, hundred-peaked, and a deep sigh scarcely sufficed to pour out the fullness of emotions that flooded me.

What a beautiful day I had spent! I had touched the soil of independent Sikkim, had seen the trouts of the Runjit, and struggled bodily with a Lepcha woman! […]

Monday, 6 March. I am leaving Darjeeling and Sikkim, tenderly and for the last time saying goodbye to the Kanchanyanga. My Bhutanese and Nepalese merchants come to say goodbye to me too, sad to see the departure of one of the good victims whom they have been fleecing on a daily basis for nearly a month.

Shortly after waking up, I looked out the window and saw them already crouching on the ground on the esplanade of the Doyls Hotel. I quickly hid myself and shut myself up to write and work. But to take my meal I had to leave my rooms, and however much I ran, they had already snagged me, offering me a large Nepalese knife, a prayer machine, a rosary, or a trumpet made of a human femur.

‘After breakfast, after breakfast …’ And off I went.