[Space] is (like time) limitless (not infinite).

—Immanuel Kant, Opus Postumum

Wahrscheinlichkeiten fallen hier gar weg, wo es auf Urteile der reinen Vernunft enkommt.

—Immanuel Kant, Critique of Judgment

We still do not know what a frontier is, or even what its nature is, except to be of nature. And we could even say that just that is the frontier: not knowing. We trace frontiers in order to know, but we will know nothing of the frontier itself. Kant is less interested in knowledge per se, pace the neo-Kantians, than in its frontier, where knowledge fails.

If there were in Kant a faculty of the frontier, it would clearly be the faculty of judgment. The success of the operation might be disputed, but the aim of the third Critique seems clear enough: that of throwing a bridge over the abyss that has opened between the world of experience and the world of freedom, between speculative and practical reason.1 The abyss is, it would seem, again what we are here calling the frontier, in a peculiarly exacerbated or exasperated form. But judgment would be the faculty allowing it to be crossed, or at least allowing the two sides to be joined. Judgment would then be reason itself being rational, the pure faculty of relations that are both singular and analogous. But it will turn out, following a fractal logic that has been appearing regularly along our path, that the frontier, and therefore judgment itself, is merely the layered multiplication of its own collapsing structure.

Let’s put this suggestion to the test of reading. We must first note a certain complication in the treatment Kant reserves for judgment. For example, in the first Critique, just where he explains the discursive character of human knowledge, Kant draws from it a primordial place for judgment. The understanding is not an intuitive but discursive faculty, because, unlike mathematics, it gives rise to a knowledge by concepts that it does not construct. But all the understanding can do with concepts is to judge with them:

Now the understanding can make no other use of these concepts than that of judging by means of them. [. . .] Judgment is therefore the mediate cognition of an object, hence the representation of a representation of it. In every judgment there is a concept that holds of many, and that among this many also comprehends a given representation, which is then related immediately to the object. We can, however, trace all actions of the understanding back to judgments, so that the understanding in general can be represented as a faculty for judging [ein Vermögen zu urteilen]. For according to what has been said above it is a faculty for thinking. Thinking is cognition through concepts. (CPR, A68–69/B93–94)

To think is to know via concepts; for us, those concepts have a discursive use; so we use them in order to judge. What is proper to the act of judgment is the fact of identifying, for a concept, a case of that concept, a case that will be subsumed under that concept. Judgment always has to do with cases, whence, a little further along in the first Critique, a more detailed description of its operation, at the very beginning of the chapter entitled “Of Transcendental Judgment in General,” where “judgment” now translates Urteilskraft. As the understanding is the faculty of rules, judgment is the power of subsuming under those rules (i.e., of recognizing cases). General logic cannot contain rules for judgment because (according to a formula Wittgenstein would later make famous) there would have to be a further rule for the application of rules, and then a rule for the application of that rule, and so on ad infinitum. Judgment is an innate capacity that cannot be taught, the Mutterwitz that no knowledge can provide or do without.2

What distinguishes transcendental judgment is that it seems that it can give itself its cases a priori and thus find its object without exposing itself to the risk that Mutterwitz will fail. Given that it deals only with the relation to an object in general, transcendental logic as such presupposes that its case is given, without having to subsume it each time. As there is transcendental logic only insofar as a possible object in general is given, this logic cannot fail to presuppose that object. But as, according to a formula Kant constantly repeats, our knowledge is limited by the bounds of possible experience, even this apparently certain judgment is oriented toward empirical judgments as alone giving it possible content. Judgment as such, then, cannot avoid the singular case, and this is what will give it its peculiar status in Kant: For judgment is presented both as a faculty and as the “faculty” of any possible distinction between faculties, the faculty of their frontiers.3

According to the definitive introduction to the third Critique, judgment has no place in doctrine, in the achieved system of a metaphysics, but only in critique. So it seems there is something properly critical about judgment. From the point of view of doctrine, there are only two types of concepts—of nature, on the one hand; of freedom, on the other. In the system, judgment, situated between these two domains, can be attached to either of these two faculties as needed. Having repeated and justified the division of philosophy into two in its first section, the introduction pulls back to consider “The Domain of Philosophy in General,” “Vom Gebiete der Philosophie überhaupt.” This is where we encounter a famous passage that tries to draw frontiers in this domain, which contains all objects of any possible application of concepts:

Concepts, insofar as they are related to objects, regardless of whether a cognition of the latter is possible or not,4 have their field [ihr Feld], which is determined merely in accordance with the relation which their object has to our faculty of cognition [Erkenntnisvermögen] in general.5—The part of this field within which cognition is possible for us is a territory [Boden, a ground] (territorium) for these concepts and the requisite faculty of cognition. [So the territory is situated within the field, is smaller than it.] The part of the territory [following a concentric progression, then] in which these are legislative [gesetzgebend] is the domain [Gebiet, the same word as for the whole space of philosophy in general: as with all legislation, what irrupts in the center is also the absolute outside] (ditio) of these concepts and of the corresponding faculty of cognition. Thus empirical concepts do indeed have their territory in nature, as the set of all objects of sense, but no domain (only their residence [Aufenthalt], domicilium) [so we are to imagine that the part of the territory that does not fall within the domain is the residence or can give rise to a residence]; because they are, to be sure, lawfully generated, but are not legislative, rather the rules grounded on them are empirical, hence contingent. (CJ, 61–62)

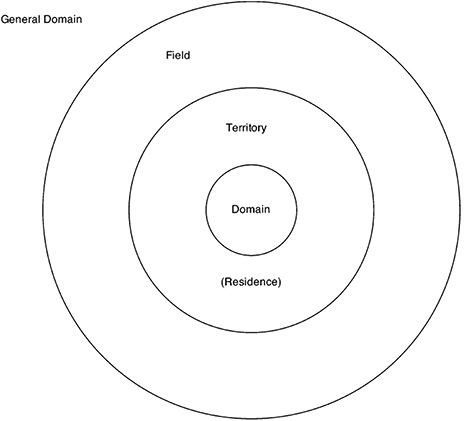

Let’s take this distribution as literally as possible. Kant implicitly invites us to draw a diagram of it, which might look like this:

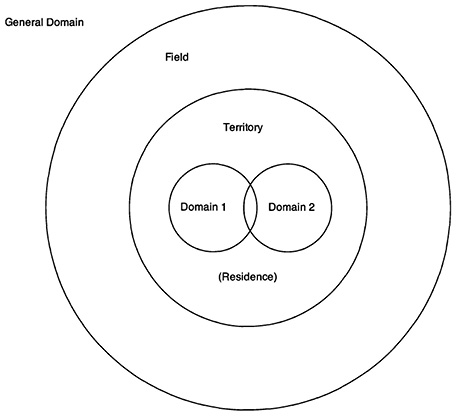

But we have immediately to complicate things, because Kant opens the following paragraph by saying that “our cognitive faculty as a whole has two domains, that of the concepts of nature and that of the concept of freedom; for it is a priori legislative through both” (CJ, 62). But the terrain or territory of these two domains is the same (the terrain of objects of possible experience), and so we must think that they can and even must share some objects, which would give the following diagram:

We shall see this still quite simple topography getting more and more complicated as Kant advances in his description. The fact that the two legislations bear on domains situated on the same terrain (domains that overlap at least somewhat, and perhaps completely) does not give rise to interferences at the level of legislation itself but to a mutual limitation (Kant uses the verb einschranken, which has become familiar to us) at the level of its effects. But the two domains remain separate to the extent that their objects are different in nature, or at least are considered in different lights or perspectives. Concepts of nature present their objects to intuition, as phenomena, whereas concepts of freedom present them as things in themselves, without that presentation taking place in intuition. Where there is theoretical knowledge, there is no thing in itself, and where there are things in themselves, there is no theoretical knowledge. Of such a “knowledge” (which if it claimed to be such would be, in us, finite beings, transcendental illusion), we must indeed have an Idea, which then takes its place in the field, but without giving rise to a terrain or, a fortiori, to a domain:

There is thus an unlimited [unbegrenztes: so we were wrong to draw a frontier around the field within the general domain, but if we erase it we are at a bit of a loss as to how to represent the relations between the field and the general domain] but also inaccessible field for our faculty of cognition as a whole, namely the field of the supersensible, in which we find no territory for ourselves, and thus cannot have on it a domain for theoretical cognition either for the concepts of the understanding or for those of reason, a field that we must certainly occupy with ideas for the sake of the theoretical as well as the practical use of reason, but for which, in relation to the laws from the concept of freedom, we can provide nothing but a practical reality, through which, accordingly, our theoretical cognition is not in the least extended to the supersensible. (CJ, 63)

This already complicates the description given by Kant because, where we thought we were dealing with a concentric arrangement of field, terrain, and domain, we now see that things are more complex. Previously, it appeared that theoretical and practical cognition each had their domain within the terrain; now, the domain of the practical is, if not identified, at least placed in a strange relation with the (now unlimited) field that surrounds the terrain. To understand what is happening here, we clearly need to introduce a dynamic element into the picture, which would allow practical legislation to take place from out of the field while still aiming at the domain inside the terrain apparently occupied by theoretical legislation. This is why the famous gulf or abyss, the unübersehbare Kluft, the cleft over which one cannot see, is not simply a division or accentuated division between two sides of the same type and also why the attempt to throw a bridge over it (the bridge of judgment) is not as easy to conceive as is sometimes thought, unless we imagine a one-way bridge:6

Now although there is an incalculable gulf fixed between the domain of the concept of nature, as the sensible, and the domain of the concept of freedom, as the supersensible, so that from the former to the latter (thus by means of the theoretical use of reason) no transition is possible, just as if there were so many different worlds, the first of which can have no influence on the second: yet the latter should [soll] have an influence on the former, namely the concept of freedom should [soll] make the end that is imposed by its laws real in the sensible world; and nature must [muß] consequently also be able to be conceived in such a way that the lawfulness of its form is at least in agreement with the possibility of the ends that are to be realized in it in accordance with the laws of freedom.—Thus there must [es muß] still be a ground of the unity of the supersensible that grounds nature with that which the concept of freedom contains practically, the concept of which, even if it does not suffice for cognition of it either theoretically or practically, and thus has no proper domain of its own, nevertheless makes possible the transition from the manner of thinking in accordance with the principles of the one to that in accordance with the principles of the other. (CJ, 63)

So if there is a possibility of transition from one domain to the other, this transition happens in one direction only (it is impossible to move from the theoretical to the practical, on pain of transcendental illusion), and this is done not by throwing a bridge over the abyss but by going under, through a tunnel; because the Kluft does have a bottom, it cuts into the common subsoil of the field, a sub-soil that is, however, super-sensible and that is shared by theoretical and practical cognition. This passage, or its possibility, is not itself of the order of theoretical knowledge. That it be possible to pass from the practical to the theoretical (that legislation according to freedom be compatible with legislation according to nature), that the moral law has effects that can be seen in the world, forms part of what makes that law the law that it is. It is duty’s duty to realize itself in the phenomenal world. The moral law must, ought, or has to be able to actualize itself in the sensible world, according to a pre- or archi-moral duty we already signaled as the archi-prescription of prescription (“do it!”): Duty owes it to itself (se doit) to make itself real. But this primary Sollen (which must precede the distinction between nature and freedom, because it is the principle of their separation and their communication), according to which one has to have effects in the world, provokes in return another duty that this time owes it to itself to be a Müssen, according to which the legality of natural legality is such that it must, by its form, lend itself to this realization of moral ends. Only this consequence gives any substance to the archi-duty of duty, because if nature did not respond, duty could owe itself to itself ad infinitum without that duty ever becoming possible to carry out. It is necessary, then, for the duty of duty to be realizable as it ought to be, failing which it would not be duty and there would be no duty. There ought to be the it is necessary that, because it is necessary that duty ought to be done. This originary connivance between necessity and obligation, nature and freedom, müssen and sollen, mechanism and ends, will make judgment (which has not yet been named in the introduction) into an essentially teleological judgment.

The sensible world is thus the end of duty, or because duty is obligatory from the end, it is the end of the end. What Kant has not yet called “judgment” will be the faculty of this doubled-up end or of this movement that carries duty toward its end and ensures that the moral law will find in the natural world the formal condition of its possible realization. Consequently, and contrary to what one might think on reading the “typic” in the second Critique, the form of law, the Gesetzmässigkeit that the moral law supposedly borrows from nature, is, rather, given to nature by the form of law of the moral law. Nature has legal form in order to respond to the moral law; natural necessity is thus dictated by the moral law, which gives a (supersensible) ground to its necessity but, at the same stroke (by digging the tunnel), undermines this ground. Because natural necessity owes itself to duty, it is no longer quite necessary or quite natural. That the (legal) form of nature must accord with the possibility of ends is its end. The end of nature is that law find its end in it. And in this way, even the archi-determinative judgment of the first Critique is already teleological, because it must presuppose that nature is such that it will provide it with cases that fit the law that the understanding is in a position to prescribe to it. This is precisely what allows for the possibility of the transcendental position itself. The understanding is thus legislative with respect to nature in a very strong sense, which involves a prescriptive or pre-scriptive element—the understanding prescribes itself a nature such that the laws it pronounces will find cases in it. Nature is in this way made for the judgment that will make a case, and this made for already gives its end to nature as able to receive practico-moral realizations. Even the subsumptive determinative judgment, then, is determined in return by its apparent other, which returns through the tunnel to pop up in the middle, like a foreign legislator.

Kant says this much later, in §76 of the Critique of Teleological Judgment. Reason demands the unification of the diverse. But the understanding, insofar as it is tied to sensibility and therefore subject to a transcendental logic (for the transcendental is less what rises away from and more what comes back down to the singular and the empirical), can only proceed from the universal to the particular, in which it cannot fail to find something contingent. This contingent element must be brought back under the law, which is done by postulating a purposiveness of the contingent as such:

But now since the particular, as such, contains something contingent with regard to the universal, but reason nevertheless still requires unity, hence lawfulness, in the connection of particular laws of nature (which lawfulness of the contingent is called purposiveness), and the a priori derivation of the particular laws from the universal, as far as what is contingent in the former is concerned, is impossible through the determination of the concept of the object, thus the concept of the purposiveness of nature in its products is a concept that is necessary for the human power of judgment in regard to nature. (CJ, 274)7

The apparently paradoxical consequence is that, for all its legality, nature must be fundamentally contingent. To be able to welcome the law, nature must not be necessary through and through. Natural necessity, seen from the point of view of its end (the law), is that it be contingent. The necessity of necessity is contingency. This chance of contingency (law’s only chance) is not knowable as such but the object of a nonknowledge that calls for what is called judgment. For us to be able to judge from the end, there must be contingency, because only contingency calls for the end as the only chance of its legality. Necessity has no end, it is blind. For the end, this blindness must blind itself again in the contingency of blind chance.

Nature, then, has an end, a purpose: that of having a purposiveness, which it has only in contingency. That there be this end comes under neither theoretical cognition (for if we could demonstrate it, we would reduce contingency to natural necessity; this is why Kant constantly repeats that the principle of judgment—namely, that we must judge as if it were made to be judged—is only subjective, or at least is not objective, while functioning just as if it were objective, because otherwise there would be no “subject”) nor practical cognition (there is no duty here) but underlies the possibility of both domains as the indispensable presupposition of their joining and separation. And yet, if this presupposition is what links the two domains beneath the abyss, it alone gives rise to the abyss. The theoretical and the practical are separated only because they are thus linked together by the purposive legality of the singular judgment. Kant’s problem in the third Critique is thus not to bring together two domains that ran the risk of being too far separated but precisely to think the frontier of these two domains, to think them together as separated. This is why, at the beginning of section 3 of the introduction, Kant repeats that we are not here dealing with a third domain but with what allows us to establish the legality of the other two domains, by tracing their frontiers:

The critique of the faculties of cognition with regard to what they can accomplish a priori has, strictly speaking, no domain with regard to objects, because it is not a doctrine, but only has to investigate whether and how a doctrine is possible through it given the way it is situated with respect to our faculties. Its field [Feld] extends to all the presumptions of that doctrine, in order to set it within its rightful limits [um sie in die Grenzen ihrer Rechtmässigkeit zu setzen]. However, what cannot enter into the division of philosophy can nevertheless enter as a major part into the critique of the pure faculty of cognition in general if, namely, it contains principles that are for themselves fit neither for theoretical nor for practical use. (CJ, §64)

The critical chance of thought (of reason insofar as it is finally, in the end, devoted to morality) would then be the frontier as a separation that allows for a passage. This chance depends on contingency, which alone bears witness to the possibility in nature of a causality other than that of mechanism, and which, extended to the system of nature as such, will tell the truth of mechanism itself, as we shall see. But then, the whole Kantian topography is turned upside down when it comes to specifying the nature and place of judgment. Kant began by establishing the apparent mutual independence of the domains of nature and freedom; he then deduced a quasi-practical quasi-necessity of a one-directional transition between the two, which alone ensured their true separation. Now he is seeking a faculty to take charge of this uniquely critical activity.

Only here does analogy intervene, and as we have had several occasions to note, analogy analogizes endlessly (or bottomlessly). The analogy is not merely the bridge (or the tunnel) that crosses the abyss, it is simultaneously the abyss itself, which is starting to provoke cracks and fissures everywhere in the fields, terrains, and domains delimited so far. Kant takes another look at the frontier between understanding and reason and finds between the two the power of judgment (here named for the first time), “about which one has cause to presume, by analogy [nach der Analogie]” that it could also (by analogy, then, with the faculties of the understanding and of reason) have the means to legislate, or rather (because what is proper to the frontier is that it is not a domain) not to have its own legislation but “a proper principle of its own for seeking laws [ein ihr eigenes Prinzip nach Gesetzen zu suchen].” Which would give judgment, qua bearer of its own principle, if not a domain (“even though it can claim no field of objects as its domain [wenn ihm gleich kein Feld der Gegenstände als sein Gebeit zustände]” says Kant, insouciantly muddying any remaining terminological clarity of his own description), at least a terrain.8

To seek laws, for what is proper to judgment as such (i.e., when it is not simply pressed into the service of theoretical knowledge—which, while being already teleological, as we saw, does not need to judge in a strong sense to the extent that the law is already given to it and it only has to subsume the case)9 is precisely to be seeking its own law. As we said, the whole Kantian system is teleological in that it is organized for the law. But we must not conclude from this, as is perhaps a common thing to do, that the law qua law is already given. To the contrary—and this is precisely why the general contingency of nature passes the understanding, which, for its part, believes in its necessity—purposiveness as legality of the contingent stretches out toward a law that has not yet come. Which is why judgment as such is essentially reflective (determinative judgment being the blind judgment of blind necessity) in search of its law. Qua reflective, judgment does not know how to judge but tries to judge. In judging, it calls for its law for which it can only wait. One can always draw a law from a judgment, but the law of judgment is that that law will never be certain. Judgment is made for a law it can never establish. Judgment itself thus has the structure of a purposiveness without purpose, a legality without law (CJ, §22), and, following the play of analogy, finds this structure in, or projects this structure into, some of the objects of its judgment. So the aesthetic judgment is “aesthetic,” and so on without end.

But this structure is that of transcendentality as such. The transcendental is a movement beyond that comes back. Experience is empirical for the transcendental—in view of the transcendental, viewed from the transcendental—as nature is contingent for the law. The transcendental comes back to the empirical as law comes back to nature. But this means that the transcendental is (no more than) the empirical that comes back (to itself). And this analogy between the transcendental and the law is, rather, an identity. The transcendental names the being-law of law as such.10 This (being-)law names a seeking after the law (still the Seefahrer or perhaps the astronaut), because we do not yet have the law and we will not have it, on pain of dogmatism: We only have the law of the law, which is its endless retreat. So the transcendental is not yet transcendental but what is nowadays called the quasi-transcendental. The transcendental can “be” transcendental only on condition of not being transcendental (for then it would be transcendent). What separates the transcendental from the transcendent is what dynamically separates the transcendental from the transcendent—namely, the frontier “itself.” Saying that this separation is dynamic is also a way of saying that it is not done but that it is doing, as the becoming-transcendent of the transcendental and the becoming transcendental of the transcendent, which is the very tracing of the frontier. Every frontier transcendentalizes to the extent that it separates, and it prevents the achievement of that transcendentalization to the extent that it joins. The transcendental is the abyssal demultiplication of the frontier, along the frontier.

This is why Kant, under the name “cosmopolitanism,” has to think at most an internationalism (the chance of cosmopolitanism lies this side of cosmopolitanism, it needs the frontier whose erasure it also projects) and why the end as (mortal) perpetual peace withdraws as a finality that must never reach its end. The chance of peace is not to be perpetual but perpetually in the process of putting off its perpetuity. Teleology thus understood puts an end to the end; it returns on itself. According to a logic that has been haunting us all along, the end of teleology is the end of teleology. “Zweckmässigkeit ohne Zweck” is no doubt naming nothing but that. “Purposiveness without purpose,” “finality without end” still has too much end in its finality. So as not to be held hostage by the end, perhaps we could try other formulations: ((finality (without end) without end)), or “((finality (without finality)) without end).”11

This could easily bring us back to Epicurus. As we have seen, every time Kant states a crucial problem for his philosophy, the ghost of Epicurus comes to prowl around. And if Epicurus, before, was opposed to Plato for the antinomy in the first Critique, and to the Stoics for the relation between virtue and happiness in the second, here he will be opposed to Spinoza. As always for what we are interested in here, the context is one of antinomy, as expounded in the dialectic of teleological judgment.

The determinative judgment cannot have an antinomy, says Kant, because it is not autonomous, does not lay down a law. However, when we are dealing with the reflective judgment—in which, as we saw, the law is not given, but where judgment gives itself the law—judgment has to follow maxims for guidance, and these maxims can enter into conflict among themselves, giving rise to the possibility of an antinomy and, therefore, a dialectic, which calls for critique. Exploring empirical nature beyond what is legislated determinatively by the categories of the understanding, we are led to invoke the maxim that all natural products must be possible according to mechanical causality but also, sometimes, especially when we come across organisms, the maxim according to which at least this part of nature (but perhaps nature as a whole, understood according to the analogy between it and the organisms it contains) can be explained only by appealing to purposive causality, to final causes. Kant’s presentation can give the impression that this antinomy is simply solved (by the end of §71, and even as early as §70, in the very statement of the antinomy, which on that reading would evaporate immediately) by insisting on the fact that these are merely maxims of investigation, regulative principles of our investigation and not constitutive principles of the objects of that investigation. There would be an obvious contradiction if one were to assert that an object were objectively caused both by natural mechanism and by final causality (a technic of nature) but no contradiction in appealing as a principle for judging nature (without claiming that this gives rise to objective knowledge), on the one hand to the maxim of mechanical causality (I have to judge according to that maxim as far as possible, for only this maxim puts me on the path to knowledge properly speaking, even if that knowledge is not determinative) and, on the other, to the maxim of final causality (when the first maxim no longer serves, I have to judge some natural objects—most notably organisms, and even, following their example, nature as a whole—according to a quite different principle, that of final causality).

Kant’s argument here is extremely delicate. If one were to maintain these two principles dogmatically (making them into determinative principles), there would indeed be an antinomy, because these two principles would be in contradiction. But as Kant points out, this contradiction would not be an antinomy of judgment, because by making these principles into principles determining objects, we would have provoked a contradiction in rational legislation itself with regard to nature, and that contradiction could not be resolved, because human reason cannot determine the objects of empirical nature. We do, of course, prescribe laws to nature, according to transcendental logic, but these laws cannot determine nature qua field of empirical investigation, in which, as we shall see in more detail, objects qua particular cases remain in part contingent with respect to the legislation of reason.

It cannot, therefore, suffice to insist that we are dealing only with maxims, regulative principles for the reflective judgment of empirical nature, in order to solve the antinomy of judgment, because it is only on the level of maxims that there is an antinomy of judgment (rather than of rational legislation itself). And yet Kant, at the end of a paragraph that presents itself as a mere preparation to the solution of the antinomy (§71: “Vorbereitung zur Auflösung obiger Antinomie”), can write the following:

All appearance of an antinomy between the maxims of that kind of explanation which is genuinely physical (mechanical) and that which is teleological (technical) therefore rests on confusing a fundamental principle of the reflecting with that of the determining power of judgment, and on confusing the autonomy of the former (which is valid merely subjectively for the use of our reason in regard to the particular laws of experience) with the heteronomy of the latter, which has to conform to the laws given by the understanding (whether general or particular). (CJ, 261)

But Kant has already explained that an antinomy of judgment can arise only if the maxims of judgment are only maxims of judgment (and not principles determinative of objects). The antinomy of judgment does not result from a confusion of autonomy and heteronomy but from the fact that judgment is autonomous. The antinomy cannot be solved by simply recalling the same antinomy. Any appearance of a legislative antinomy (an insoluble contradiction) is removed by recalling the maxim-status of the mechanistic and finalist principles. It still remains to resolve the properly judgmental antinomy that results—the resolution of the antinomy of judgment is prepared by removing any appearance of an antinomy in the law.

So where exactly do we find the antinomy that remains to be resolved? In the very presentation of the antinomy in §70, Kant seems to suggest that the coexistence of the two maxims is fundamentally peaceful. But this peace of judgment about nature does not result from the equal status of the two maxims but a subordination of the one to the other, in the name of knowledge:

For if I say that I must judge [beurteilen] the possibility of all events in material nature and hence all forms, as their products, in accordance with merely mechanical laws, I do not thereby say that they are possible only in accordance with such laws (to the exclusion of any other kind of causality); rather, that only indicates that I should [soll] always reflect on them in accordance with the principle of the mere mechanism of nature, and hence research the latter, so far as I can, because if it is not made the basis for research then there can be no proper cognition of nature [keine eigentliche Naturerkenntnis]. Now this is not an obstacle to the second maxim for searching after a principle and reflecting upon it which is quite different from explanation in accordance with the mechanisms of nature, namely the principle of final causes, on the proper occasion, namely in the case of some forms of nature (and, at their instance, even the whole of nature). (CJ, 259)

So the point is not to have both maxims available and choose one or other arbitrarily. In the perspective of knowledge, the principle of mechanical causality (in harmony with everything in the understanding that is legislative with respect to nature) comes first, and we stick with it as long as possible, moving to the other maxim only when the mechanistic explanation comes up short (for example, when faced with organisms). However—and this is where the antinomy will come into its own—the odd occasions on which one appeals to the purposive principle of judgment also serve as a pretext or a motive to judge similarly of nature as a whole (judging that nature is fundamentally teleological), which cannot fail to bring about a conflict between the two maxims, which henceforth are trying to apply to the same objects at the same time. The antinomy comes about as a result of abandoning any dogmatic claim to knowledge, which allows free competition between the two maxims of judgment.

We do not know if mechanical causality suffices to account for everything that is in nature, and we do not know this because natural particularities and their laws are, for us, empirical and therefore, at least in part, contingent. So we know that we cannot know nature through and through according to mechanical causality, despite the infinite field for judgment opened up by this principle in the scientific investigation of nature. We know that for us mechanical causality does not account for everything (for example, organisms). We could simply leave things at that (and there would be no antinomy). If our investigation of nature is driven by the search for scientific knowledge, we will follow the mechanistic maxim as far as possible, and the purposive maxim as regards organized beings, without further elaborating the “speculative” question of knowing whether (without making it a determinative principle) this latter maxim does not tend toward an inclusive understanding of nature as such, which would reverse the order of the hierarchy of maxims in favor of the maxim of purposive causality. That maxim tells us to judge as if nature involved a final causality, and for the purposes of the investigation of nature we can and even must remain with this subjective status of the maxim without making more of it. But we might also ask (while ruling out any theoretical knowledge in this respect) whether the invitation nature gives us to judge it according to the maxim of final causality does not take us further:

Now one could leave this question or problem for speculation entirely untouched and unsolved, for if we are satisfied with speculation within the boundaries [Grenzen] of the mere cognition of nature, the above maxims are sufficient for studying nature as far as human powers reach and for probing its most hidden secrets. [But to the extent that we are not satisfied with this, and do try to go beyond those limits] It must therefore be a certain presentiment [Ahnung] of our reason, or a hint as it were given to us by nature, that we could by means of that concept of final causes step beyond nature and even connect it to the highest point in the series of causes if we were to abandon research into nature (even though we have not gotten very far in that), or at least set it aside for a while, and attempt to discover first where that stranger [Fremdling] in natural science, namely the concept of natural ends, leads. (CJ, 261–62)

Suspending scientific research in this way, in the name of speculative reason, does not mean one is falling back into the dogmatism that consisted in taking a subjective principle for a determinative principle but rather opening a question, a problem, as Kant says, “a wide array of controversial problems.” And these controversies have indeed taken place in the tradition: Either it has been asserted that the technic of nature (its at least apparent operation according to final causality) is not intentional (and thus is not really a final causality but rather “identical with the mechanism of nature or dependent on one and the same ground, where, however, since in many products of nature this ground is often too deeply hidden for our research, we attempt to ascribe it to nature by analogy with a subjective principle, namely that of art, i.e., causality in accordance with ideas” [CJ, 181]) or that it is intentional and that there really is a final causality. Kant, running the risk of confusing the reader, calls the claim that the technic of nature is not really one the system of idealism (in the sense that the final causality operates only at the level of the idea) and realism the system according to which there really is such a final causality.

As is often the case in Kant, there is some degree of convergence between the history of philosophy and the a priori deductions of reason: Reason alone suggests a matrix of four possible ways of approaching the problem of the objective purposiveness of nature—and it turns out that these four possibilities have indeed been realized in the texts of the tradition. Kant, very satisfied with this convergence, which means that the dogmatic resources of reason have all been exploited, henceforth leaving room only for critique (according to the schema laid out in the first preface to the first Critique), adds a footnote:

One sees from this that in most speculative matters of pure reason the philosophical schools have usually tried all of the solutions that are possible for a certain question concerning dogmatic assertions. Thus for the sake of the purposiveness of nature either lifeless matter or a lifeless God as well as living matter or a living God have been tried. Nothing is left for us except, if need be, to give up all these objective assertions and to weigh our judgment critically, merely in relation to our cognitive faculty, in order to provide its principle with the non-dogmatic but adequate validity of a maxim for the reliable use of reason. (CJ, 263n)

If we clearly must not conclude too rapidly that, in order to orient himself in thinking, Kant begins by appealing to the tradition, we must also beware of accepting too readily that critique has been able to overcome that tradition. As we shall see, Kant has the greatest difficulty establishing the status of his “maxims” here (the whole drama of this antinomy) and, by the same token, separating the properly critical moment of his thinking from what the tradition presents dogmatically. As we shall not cease verifying, it is contingency that plays a crucial role here, and we shall see that, in spite of appearances, it is again from Epicurus that Kant will have the greatest difficulty taking his distance.

Each of Kant’s two ways of approaching the problem in turn divides into two. On the side of idealism, we have on the one hand, as we saw earlier, Epicurus (and Democritus), and on the other Spinoza:

The idealism of purposiveness (I always mean objective purposiveness here) is now either that of the accidentality or of the fatality of the determination of nature in the purposive form of its products. The first principle concerns the relation of matter to the physical ground of its form, namely the laws of motion; the second concerns the hyperphysical ground of matter and the whole of nature. The system of accidentality, which is ascribed to Epicurus or Democritus, is, if taken literally, so obviously absurd that it need not detain us; by contrast, the system of fatality (of which Spinoza is made the author, although it is to all appearance much older), which appeals to something supersensible, to which our insight therefore does not reach, is not so easy to refute, since its concept of the original being is not intelligible at all [nicht zu verstehen ist]. (CJ, 263)

This “absurdity” of the Epicurean system (Democritus never reappears in the rest of the text and the question of any differences there may be between Democritus and Epicurus, which was to occupy a young German philosopher a few decades later, is not even raised), which is here dismissed in the same way as in the “Universal History” text, is the object a little later of a fuller explanation as to its absurdity:

The systems that contend for the idealism of final causes in nature [i.e., those who argue that there are no such causes objectively speaking] concede to its principle a causality according to laws of motion (through which natural things purposively exist [i.e., there is an appearance of purposive causality, which is really only a mechanical causality]), but they deny intentionality to it, i.e., they deny that nature is intentionally determined to its purposive production, or, in other words, that an end is the cause. This is Epicurus’s kind of explanation, on which the difference between a technique of nature and mere mechanism is completely denied [according to Epicurus there is only mechanical causality that, in some cases, produces effects which misleadingly seem to have been produced by final causality], and blind chance is assumed to be the explanation not only of the correspondence of generated products with our concepts of ends, hence of technique, but even of the determination of the causes of this generation in accordance with laws of motion, hence of their mechanism, and thus nothing is explained, not even the illusion in our teleological judgments, and hence the putative idealism in them is not demonstrated at all. (CJ, 264)

As always, the rejection of Epicurus turns out to be more complicated than Kant’s initial gesture would suggest. For what is the basis of the refutation here? Not, as one might have expected, the fact that Epicurus simply denies all final causality in the name of mere mechanism (which would be enough to motivate rejection on the grounds of dogmatism, as in the first Critique, where, it will be remembered, the ambiguity in the presentation of Epicurus depended on the possibility of making his [anti-]theses into mere hypotheses leading to an enlargement of knowledge) but indeed the way he understands mechanical causality itself when he writes it off to chance. According to Epicurus as read by Kant, the only causality is causality by chance, which immediately removes all possibility of understanding anything at all. The appearance of final causality is then “explained” by the reality of a mechanical causality, which is not even a causality because it rests entirely on chance. Epicurus, called in to show that the appearance of finality in nature is not the result of an intention, shows too much from Kant’s point of view by refusing even the principle of nonintentional mechanical causality, which makes the question of causality in general fall even below the opposition between intentionality and nonintentionality into pure chance, which explains nothing and is absurd by virtue of invoking absurdity (chance) as the principle for explaining anything at all.

So chance remains in an excessive and eccentric position with respect to the needs of Kant’s demonstration. To fill this square in his matrix (the nonintentional/idealist square), Kant did not need a doctrine as radical as that of Epicurus, which, as he presents it, is not even a mechanistic dogmatism. Unless—and this is the suspicion that will henceforth guide our reading of the antinomy—in Kant’s logic, mechanism without final causality will always be doomed to the abysses of chance, in which case, as always, Epicurus, excessive with respect to the position Kant assigns to him in the demonstration he is attempting here, will not really have been dismissed and will continue to prowl around the antinomy as what we might call its negative resource.

Recall Kant’s procedure thus far. The antinomy of judgment results from the possibility for reason to appeal, in its consideration of nature, to two incompatible maxims: This antinomy is an antinomy of judgment—rather than a contradiction in the legislation of reason itself—only to the extent that we are in fact dealing with two maxims (regulative principles). In the perspective of the investigation of nature (in the optic of natural science), the coexistence of these two maxims is not a problem so long as we give priority to the maxim of mechanical explanation and follow it as far as possible, appealing to the finalist maxim only when the former no longer works (i.e., as we shall see, at the moment of contingency). But, following the (natural) movement of speculation, one can suspend this priority of the mechanical maxim and give priority to the finalist maxim, on the grounds that natural contingencies (as seen from the point of view of mechanism) may give us a clue as to a more inclusive natural purposiveness to which our reason cannot be indifferent and which would indeed be the question of transcendental philosophy. In the tradition, there are four main ways of dealing with this problem of at least apparent natural purposiveness, but the Epicurean way is absurd, for not only does it attempt to reduce purposiveness to mechanism (which in itself is not so different from what the naturalist must do to attain a true knowledge of nature), it also reduces mechanism to chance. It remains to be shown that that is the fate of all mechanistic explanation as such (and thus of any knowledge of nature in the theoretical sense and, in the end, of any determinative judgment) if it is not subordinated to the finalist maxim, which by the same token becomes much more than a simple “subjective” maxim. And this disturbs all the oppositions on the basis of which Kant is trying to think here, beginning with the oppositions between the constitutive and the regulative,12 the determinative and the reflective, the contingent and the necessary, among others. In this perspective, the excessive position of Epicurus will give us something like a negative truth of Kant’s thinking.

Kant thus disposes of the four traditional ways of dealing with the question of natural purposiveness: Epicureanism is “absurd,” as we have just seen; Spinozism is unintelligible, in that it ends up positing a “blind necessity” (CJ, 265) that is the counterpart of the “blind chance” (CJ, 264) of Epicureanism; hylozoism is unsatisfactory because not only is the attribution of life to matter a simple category error but it also relies on a vicious circle (we suspect on the basis of organisms that nature as a whole is perhaps also organized in terms of final causality; hylozoism explains the purposiveness of the parts by simply presupposing the purposiveness of the whole, which is what we were supposed to be explaining); and theism is dogmatic in that we would first have to prove the impossibility of an exhaustive explanation according to mechanical causality before having grounds to posit in determinative fashion the existence of a superior intelligence outside nature. Having thus disposed of the four traditional ways of dealing with the problem, Kant needs to motivate the properly critical explanation of the antinomy (and even the bare presentation of the antinomy, because we are still waiting to find out exactly how this antinomy really is an antinomy), and this he attempts in §74. To have grounds for a dogmatic use (for a determinative judgment, then) of the concept of a thing as a natural end (namely the concept of a thing as part of a nature subject to final causality), we would have to be able to establish the objective reality (“objective,” as always in Kant, according to the conditions of possibility of an experience for us) of this concept. One might be tempted to think that this concept must be objective, because it is undeniable that it comes to us in a context of empirical conditions, which must be subject to the laws of the understanding in general, which would then provide the necessary principle of subsumption. But we cannot abstract this concept from experience (i.e., produce it qua concept by a process of abstraction from the singular conditions in which it shows up in given empirical situations), because it is a concept possible only as a rational principle of the judgment we bring to bear on the object. Which amounts to saying that we can never see a natural end as such (in a moment we shall see that all we ever see is a contingency), but we can judge a given object as being the result of a causality other than a mechanistic causality. But judging in this way, according to a rational principle indeed, but one the objective validity of which remains undemonstrable, we cannot be proceeding by subsumption according to a determinative judgment. So the principle remains regulative for a reflective judgment and thus susceptible to a treatment that is merely (but radically) critical (i.e., one that, given the position of judgment as we saw it in the introduction, cannot ever advance beyond critique to doctrine).

Because the judgment brought to bear according to this principle is necessarily brought to bear on the basis of a natural datum (what we judge to be a natural end—an organized being—is indeed found in nature), it seems to involve a contradiction, which will be the formal marker of the impossibility in which we find ourselves of making it into an objectively established concept giving rise to determinative judgments (and therefore objective knowledge). For to the very extent that the object in question is found in nature, it must necessarily involve necessity entailed by laws, whereas qua natural end it involves contingency with respect to those same laws. So the antinomy properly speaking is here: The point is not that we can invoke one or other of two maxims of investigation of which the one relays the other when the first fails, because the concept that guides one of those maxims (at least) (i.e., the one that guides the purposive maxim) is apparently split by two contradictory suppositions, of necessity and of contingency. This antinomy (in the very concept of natural end) can be resolved, says Kant, only by placing “end” and “nature” on radically different planes, which has as a consequence that the concept of natural end can never be objectively established:

As a concept of a natural product it includes natural necessity and yet at the same time a contingency of the form of the object (in relation to mere laws of nature) in one and the same thing as an end; consequently, if there is not to be a contradiction here, it must contain a basis for the possibility of this thing in nature and yet at the same time a basis of the possibility of this nature itself and its relation to something that is not empirically cognizable nature (supersensible) and thus is not cognizable at all for us, in order to be judged in accordance with another kind of causality than that of the mechanism of nature, if its possibility is to be determined. (CJ, 267)

The contingency with respect to mechanical causality revealed by the form of organized beings, then, refers us not only to a different maxim to guide our research but refers us beyond nature as such, or at least toward a thinking of the whole of nature as grounded in something nonnatural and unknowable. The impossibility of getting to the end of our determinative-subsumptive judgments according to mechanical causality, the fact that we stumble over contingencies (namely, objects the organization of which is indubitable and yet escapes our mechanistic explanations), does not allow us to posit a purposive causality as objective (because we understand it not at all) but obliges us to think of the possibility of nature in general, the sphere of mechanical causality, as not itself falling, qua totality, under the law of that same mechanical causality that, in general, holds sway within it.

So the antinomy resides in the fact that, faced with organized beings, we find ourselves unable not to appeal simultaneously to both causalities, and its resolution consists in referring purposive causality (which had appeared in nature in the form of organized beings, which are contingent with respect to mechanical causality) to the unknowable (and hence super-natural) realm of the supersensible. The concept of natural end will, then, remain forever problematic and will never be able to motivate dogmatic responses, be they positive or negative. The concept of purposive causality does indeed exist objectively (as in human art and technology), as does that of a mechanical natural causality; what cannot attain to such objectivity is the concept of a natural purposive causality, for such a concept cannot be drawn from experience (by abstraction, as we were just saying) or posited as necessary for an experience to be possible. Such a concept will remain forever problematic because even if, per impossibile, I managed to show that some natural objects really were the intentional productions of a divine artistic understanding, I would in so doing simply withdraw them from the domain of nature, whereas the problem was that of knowing now to understand them as natural products. We can preserve the naturality of nature only by invoking in a merely problematic way a concept the (positive or negative) objectivity of which will never be established. Nature needs this strange concept of a nature other than simply natural nature, this phantom nature of which all we know is that we need it. I will attempt to show that once again this structure is that of transcendentality itself.

The fact that this concept is fundamentally problematic, then, does not above all mean that we could do without it. The problematic concept of natural end is in a certain sense necessary. How? In that it is necessary for necessity. We saw earlier that the study of nature in view of knowledge must lean toward the maxim of judgment according to mechanical causality, a judgment that is perfectly in accord with the necessary, determining, character of the law of nature (even if that law be, in the event, an empirical one). But the movement of Kant’s thought, which consisted initially in “suspending” this investigation to answer the speculative, transcendental call of the other maxim, leads to the point where, at least when faced with organized beings, it is impossible for us not to invoke the two causalities simultaneously and to refer the second to the unknowable supersensible. But this (“subjective,” regulative, problematic) reference of purposive causality beyond nature as such turns out, after the suspension of scientific investigation, to be indispensable to the progress of that investigation and even to its possibility as such.

Because, as Kant says in §75, the fact of making the concept of natural purposiveness merely a principle of my judgment (the result of the particular, limited, constitution of human rationality) merely confirms the necessity of this concept that escapes natural necessity: “It is in fact indispensable for us to subject nature to the concept of an intention if we would even merely conduct research among its organized products by means of continued observation; and this concept is thus already an absolutely necessary maxim for the use of our reason in experience” (CJ, 269; emphasis added). This necessity as regards organized beings taken piecemeal, as it were, cannot fail, as we have seen, to lead us to thinking about nature as a whole. Now Kant, having established—contrary to the apparent movement of the beginning of the antinomy, which seemed to concede priority when it came to knowledge to the maxim of mechanical causality—that we must necessarily invoke the purposive maxim for all knowledge of organized beings, wants to move on to the totality without giving up on the question of knowledge (the necessity of the purposive maxim for knowledge of some beings must lead us to try it out on nature as a whole) but does not want to suggest that the problem is still essentially situated on the same level. Whence a paragraph that has to start out on the terrain of knowledge in order to jump beyond it:

It is obvious that once we have adopted such a guideline [ein solcher Leitfaden] for studying nature and found it to be reliable we must [müßen] also at least attempt to apply this maxim of the power of judgment to the whole of nature, since by means of it we have been able to discover many laws of nature which, given the limitation of our insights into the inner mechanisms of nature, would otherwise remain hidden from us. [Do not, however, imagine that that is the principal reason for performing that extension:] But with regard to the latter use this maxim of the power of judgment is certainly useful, but not indispensable, because nature as a whole is not given to us as organized (in the strictest sense of the term adduced above). By contrast, this maxim of the reflecting power of judgment is essential [essentially necessary, wesentlich notwendig] for those products of nature which must be judged only as intentionally formed thus and not otherwise, in order to obtain even an experiential cognition of their internal constitution; because even the thought of them as organized things is impossible without associating the thought of a generation with an intention [mit Absicht]. (CJ, 269)

So the finalist maxim leads us, on the basis of its grounding at the level of knowledge, to ask the question of the totality of nature. This question cannot, strictly speaking, be situated at the level of empirical knowledge (the maxim can always serve as a maxim for knowledge but does not essentially enter into the thought of nature as totality). But at least this much follows: The purposive maxim has turned out to be necessary as regards a part of nature (namely, organized beings). And this necessity of the purposive maxim also makes necessary the thought of a certain contingency of nature (thought of as mechanism). But if nature is therefore not thinkable (by us) as entirely necessary, then nature qua totality must itself be considered to be contingent and must therefore, still for us, be thought of as the work of a super-natural intelligence:

Hence natural things which we find possible only as ends constitute the best proof of the contingency of the world-whole [der vornehmsten Beweis für die Zufälligkeit des Weltganzen], and are the only basis for proof valid for both common understanding as well as for philosophers of the dependence of these things on and their origin in a being that exists outside of the world and is (on account of that purposive form) intelligent [verständigen]; thus teleology cannot find a complete answer for its inquiries except in a theology. (CJ, 269)

So by dint of explicating what is merely a maxim of the faculty of reflective judgment, Kant has sent us off beyond nature as such, toward God. But, according to a movement that is none other than the becoming-transcendent of the transcendental, this movement runs the risk of carrying us much too far. The thought of a purposive causality in nature can only refer us beyond nature to God, but it will never demonstrate the existence of God, which remains, then, here at least, a purely subjective necessity of our limited faculty of judgment. We can never establish the existence of God in this way because, as Kant recalls, we can never see natural ends as such, but only certain objects the thought of which we cannot even formulate without judging according to final causality.

The whole teleology, which thus finds its end in a theology, is radically subjective. What does this mean here? That human reason, which is, ex hypothesi, limited compared to the reason of other possible rational beings, cannot do without the purposive maxim (or, therefore, its theological consequence) and that the limit of reason that makes the maxim necessary for us simultaneously makes impossible for us any objective proof in this regard. Such an objective proof (which would establish that final causality is constitutive of the object and not merely regulative for the judgment we are in a position to bring to bear on the object) would be equivalent to showing that the maxim in question was valid not only for us but also for superior intelligences. And one senses the impossibility of such a demonstration: To the very extent that human reason is limited, any conception of a reason that could go beyond those limits is itself limited by the very limits it would be claiming to go beyond, according to the very structure of transcendentality, the structure of the Grenze—we transgress the frontiers of human reason only to the extent that we are transgressing frontiers, which thus by definition hold us short of what such a transgression wanted to achieve. One can cross the frontiers of human reason only the better to draw them. Any “objective” proof is thereby circumscribed, and everything that is not susceptible of objective proof (including the very objectivity of that objectivity, as we shall see in a moment) never will be. So it is not simply that we are condemned to appeal to the purposive maxim because of a negative limit from which superior intelligences would not suffer, because the very idea of such intelligences is positively produced only by the structure of that same limit (and so the infinite is finite). The limit produces both what is limited and what is beyond it, but what is beyond it is beyond it by the very fact of this limit. Reason thus produces itself both as understanding (at home inside the limit, grounding an “objectivity” entirely subordinate to the limit) and as reason (the limit itself as a bilateral frontier folding its outside back toward its inside, whence it cannot fail to externalize itself, to turn itself back out). This is literally what Kant says in the “Remark” that is §76:

Reason is a faculty of principles, and in its most extreme demand it reaches to the unconditioned, while understanding, in contrast, is always at its service only under a certain condition, which must be given. Without concepts of the understanding, however, which must be given objective reality, reason cannot judge at all objectively (synthetically), and by itself it contains, as theoretical reason, absolutely no constitutive principles, but only regulative ones. One soon learns that where the understanding cannot follow, reason becomes excessive, displaying itself in well-grounded ideas (as regulative principles) but not in objectively valid concepts; the understanding, however, which cannot keep up with it, but which would yet be necessary for validity for objects, restricts the validity of those ideas of reason solely to the subject, although still universally for all members of this species, i.e., understanding restricts the validity of those ideas to the condition which, given the nature of our (human) cognitive faculty or even the concept that we can form of the capacity of a finite rational being in general, we cannot and must not conceive otherwise, but without asserting that the basis for such a judgment lies in the object. (CJ, 271–72)

One senses that all of Kant’s frontiers are beginning to tremble here. On the basis of the apparently anodyne antinomy of the faculty of judgment (judge according to mechanism or purposiveness), Kant, having apparently defused the antinomy by appealing to the merely subjective character of the maxims in question, has, by exploring further the very subjectivity of the purposive maxim, exceeded nature as a whole to ground it in a principle of subjectivity that is so radical that it removes any “objective” definition of objectivity. The objectivity of the objective is overtaken by a principle that can never achieve objectivity (while dealing it a radical blow) and whose supposed “subjectivity” de jure precedes the very opposition of subjective and objective. The understanding (and thereby any use of the faculty of determinative judgment) is in the service of a reason that is merely the exposure of that understanding to its own frontier, where its finitude is, as it were, denounced before a principle of excess that is none other than the supposed regulative principle of reflective judgment itself. Qua rational (excessive), the reflective judgment (always, it will be remembered, in search of its law) “grounds” the understanding in an “objectivity” that is strangled by the subjective finitude of a reason that is only its own turning back toward an absolute exteriority. It will follow that henceforth Kant will have the greatest difficulty maintaining clear frontiers between the subjective and the objective, the constitutive and the regulative, the dogmatic and the problematic, the understanding and reason, the critical and the doctrinal.

This consequence can, clearly enough, give rise to two apparently opposite movements. On the one hand, Kant can register a certain satisfaction of human reason, grounded on the resemblance between what is objective and what is subjective but necessary to the subject insofar as it can have objects. He says in §75:

Now if this proposition, grounded on an indispensably necessary maxim of our power of judgment, is completely sufficient for every speculative as well as practical use of our reason in every human respect, I would like to know [so möchte ich wohl wissen] what we lose by being unable to prove it valid for higher beings, on purely objective grounds (which unfortunately exceed our capacity). (CJ, 270; Paul Guyer adds a question mark here not found in the German text)

But this implied rhetorical question (“I would like to know”) and the satisfaction it might indicate if we take it to be a rhetorical question also invite a more literal reading:13 I would like to know, I would really like to know, but everything I have said shows that unhappily I can never know, only judge. Human reason, just now self-satisfied, is here somewhat needy and miserable. What we lack will never be the object of theoretical knowledge for us, just because we lack it. But just this indeterminate lack is the principle of judgment as reflective judgment—that is, as characterized by lack (of the law for the case). The self-sufficiency and self-satisfaction of human reason are thus grounded in its radical insufficiency as understanding, its deficit of objectivity that thus becomes the reason of (human) reason itself.

Human reason is in this way characterized by a certain necessity of contingency. The nonobjectivity of the principle of purposive causality, the absence of the law for some cases at least, the contingency in and of nature are necessary for our understanding. This curious necessity drives Kant to give “examples” in this remark to §76, “examples, which are certainly too important as well as too difficult for them to be immediately pressed upon the reader as proven propositions, but which will still provide material to think over and can serve to elucidate what is our proper concern here.”14

And indeed, two examples will prepare the way for what we have just called the necessity of contingency. First “example”: It is necessary for human understanding to make a distinction between possibility and actuality (Wirklichkeit). We can represent a thing to ourselves (by its concept) without that thing’s being actually given to us. The actuality of things comes to us solely via our sensibility, according to the first Critique’s intuitus derivativus (B72). But we can imagine (in the modality of the possible, then) an understanding that would give itself objects directly by thinking them, without it being necessary for it to go via sensibility. For such an understanding, the distinction between possibility and actuality would be irrelevant, whereas for us (who need such a distinction), such an understanding is thinkable only according to one of the terms of that same opposition. An understanding (impossible for us) that would not recognize the meaning of possible can be represented (possible for us). One of terms of this opposition (necessary for us) allows us to think its nonpertinence. But this radicalization of the possible is only possible. The possible (as opposed to the actual) remains necessary for us so we can represent to ourselves, in the mode of the possible, its disappearance into an identity with the actual. The possibility of representing the end of the possible thus confirms the necessity of the possible. The very fact of the separation of sensibility and understanding allows us to think their nonseparation.

This separation of the possible and the actual for us is none other than the separation between the necessary and the contingent. The absolutely necessary (where the separation of the possible and the actual would lose all relevance) is only possible and thus contingent. The contingent is necessary for us to be able to represent its disappearance in the absolutely necessary.

Second “example.” Just as we must (necessarily) admit necessity (in the mode of the contingent), we are conscious of the moral law, and we must thus presuppose causality through freedom:

Now since here, however, the objective necessity of the action, as duty, is opposed to that which it, as an occurrence, would have if its ground lay in nature and not in freedom (i.e., in the causality of reason), and the action which is morally absolutely necessary [die moralisch-schlechtin-notwendige Handlung] can be regarded physically as entirely contingent (i.e., what necessarily should [sollte] happen often does not), it is clear that it depends only on the subjective constitution of our practical faculty that the moral laws must [müßen] be represented as commands (and the actions which are in accord with them as duties), and that reason expresses this necessity not through a be [Sein] (happening [Geschehen]) but through a should-be [Sein-Sollen]. (CJ, 273)

So there is necessity and necessity. The morally necessary is physically contingent (what ought necessarily to happen must not necessarily happen, and even most often does not happen, might even never happen, is totally contingent, necessarily contingent). Why is this? Because reason is not mankind’s only faculty, it is related to sensibility and thereby to nature (to a possible nature). The thing that gives nature as an object of possible experience, and as object of such an experience, as phenomenon, what gives rise to theoretical knowledge and to the necessity of Sein or Geschehen—namely, sensibility—by the same token withdraws Sein from the intelligible world and gives it the Sollen. And this is another version of the paradox of the possible and the actual that we were just reading. The fact of sensibility here gives the separation of possible and actual as the separation between Sein and Sollen:

Which would not be the case if reason without sensibility (as the subjective condition of its application to objects of nature) were considered, as far as its causality is concerned, as a cause in an intelligible world, corresponding completely with the moral law, where there would be no distinction between what should be done and what is done, between a practical law concerning that which is possible through us and the theoretical law concerning that which is actual through us. (CJ, 273)

Just as it is possible for us to represent to ourselves a world in which the modality of the possible would not have a place, it is equally possible—and in fact we ought, this is duty itself—to represent to ourselves a world from which duty would be absent, in which Sollen would merge with Sein, in which the law would not take the form of a command that constrains us. It is possible for us to do so, and in fact we ought to do so; this means also that we are free to do so. That is what freedom is. If freedom qua “formal condition” of this intelligible world, in which Sollen and Sein merge, remains for us an excessive concept (überschwenglicher Begriff) that can determine nothing as to objective reality, this is because “freedom” has meaning for us (doubly for us: once as our freedom itself, a second time as our concept or Idea of that freedom) only to the extent that it does not dissolve in a purely intelligible world (that would by this very fact be unintelligible for us) in which causality by freedom would merge with causality by necessity and would find its end in that merging. Which is, of course, the meaning of what Kant is trying to think under the name of regulative principle, which brings with it the whole issue of the Ideas of Reason.

So, for us, freedom will consist exemplarily (recall that we are dealing with “examples” in §76) in thinking nonobjectively the end of freedom in the (un)intelligible world. To give any meaning to freedom, we must, then, be in part constrained by a mechanical necessity (in sensible nature) and thus equally constrained by the moral law that presents itself to us as imperative and command. And this free thought of freedom—which is free only by dint of constituting nothing objectively, by dint of its ought-to-be-realized in a world in which, if in fact it were realized, it would not be free—which, says Kant, by making of freedom a mere regulative principle “does not determine the constitution of freedom, as a form of causality, objectively,” this thought in no way devalues freedom by refusing it any objective status but “indeed does so with no less validity than if it did determine freedom objectively [mit nicht minderer Gültigkeit, als ob diese geschähe].” Being able to represent to ourselves a world in which freedom and necessity would merge like actuality and possibility, then, we can only represent such a world to ourselves, and the only chance we have of representing it is by hanging on tight to the very distinction the disappearance of which that representation seems to promise. Our freedom depends on our possibility of representing its end and so depends on our having of freedom a final idea. According to a schema that Kant is about to refine and aggravate, but which we shall see to be the schema of the Ideas as such, the Idea of freedom is an Idea only to the extent that it projects its own end (i.e., the moment at which it would become concept rather than Idea, constitutive rather than regulative principle, or at least the moment at which these distinctions would disappear in what they made possible). Kant says that it has no less value than if it were the case; but if it were the case it would have no value at all, because “being the case” here is precisely geschähe, and as we have seen, geschehen is on the side of Sein, not of Sein-Sollen. The case as such cannot be free.

Freedom considered as the formal condition of an intelligible world is, then, inaccessible to us as an objective concept and must remain forever problematic. But the freedom of freedom consists in precisely this problematic status. And it is precisely this structure (which is, I repeat, the same as that of transcendentality as such) that Kant will formalize under the name of purposiveness. For the two “examples” he has just given serve to elucidate a thinking of purposiveness that thinks together lawfulness and contingency even before the distinctions between concept and Idea, theory and practice, etc.

Recall the abyssally analogical structure of §76, which condenses the very structure of Kant’s thought, at least as it is expounded in the introduction to the third Critique. The examples given by Kant are linked by operators of analogy that have a cumulative effect:

Just as [So wie] in the theoretical consideration of nature reason must assume the idea of an unconditioned necessity of its primordial ground, so, in the case of the practical, it also presupposes [so setzt sie auf] its own unconditioned (in regard to nature) causality, i.e., freedom, because it is aware of its moral command [. . .] Likewise [Ebenso] [. . .] (CJ, 273–74; emphasis added)

The first two examples have opened the way to what will bring the series to an end. They have allowed us to think what one might call a certain free possibility that can only be thought in the evanescent perspective of its own disappearance, a perspective called “Idea.” This thought will now find a formulation that, in the context of a judgment supposed to give a certain mediation between theory and practice, will in fact enfold and transgress them at one and the same time. Ebenso, then:

Likewise, as far as the case before us is concerned [was unsern vorhabende Fall befrifft: that is, the case of judgment (which is always judgment of a case) insofar as it is divided in its antinomy between mechanism and purposiveness], it may be conceded that we would find no distinction between a natural mechanism and a technique of nature, i.e., a connection to ends [Zweckverknüpfung] in it, if our understanding were not of the sort that must go from the universal to the particular, and the power of judgment can thus cognize no purposiveness in the particular, and hence make no determining judgments, without having a universal law under which it can subsume the particular. But now since the particular, as such, contains something contingent [etwas Zufälliges] with regard to the universal, but reason nevertheless still requires unity, hence lawfulness, in the connection of particular laws of nature (which lawfulness of the contingent is called purposiveness [emphasis added]), and the a priori derivation of the particular laws from the universal, as far as what is contingent in the former is concerned, is impossible through the determination of the concept of the object, thus the concept of the purposiveness of nature in its products is a concept that is necessary for the human power of judgment in regard to nature but does not pertain to the determination of the objects themselves, thus a subjective principle of reason for the power of judgment which, as regulative (not constitutive), is just as necessarily valid for our human power of judgment as if it were an objective principle. (CJ, 274)