Monsignor Escrivá and his daughters

A

car pulled up at the front door of Villa delle Rose, in Castelgandolfo outside Rome, and Monsignor Escrivá got out quickly, eager to see his daughters. He always liked to bring a present when he came to see them. Sometimes he would bring sweets, other times some china ducks or other ornaments for the house. Today, June 17, 1964, it was some records and an antique fan for the collection in their sitting room.

In no time at all, a lively get-together started. Joan McIntosh, an American, asked him why family life was the heart and soul of people’s relations in the Work. Monsignor Escrivá smiled. “As a teacher, you know how to explain it perfectly to other people—but you want to hear me say it, don’t you? You know we call it ‘family life’ because the same atmosphere exists in our houses as in Christian families. Our houses aren’t schools, or convents, or barracks: they’re homes where people with the same parents live. We call God himself Father, and the Mother of God, Mother. What’s more, we really love each other.”

Monsignor Escrivá made an eloquent gesture, interlacing the fingers of both hands like the weave of a basket. “We really love each other! I don’t want anyone in the Work to feel alone!”

1

He often said that he was “not a model for anything,” but he would make one exception. “If I were an example of anything, it would be that of a man who knows how to love.”

Those who lived with him, even for a few hours, could feel that. One of his sons in Opus Dei said, “When you were with the Father you felt looked after, cared for, well treated, and loved. You always received more than you asked for, more than you had realized you needed.

“It wasn’t that he had a fabulous memory, so that on seeing you he was reminded of the problem of that friend of yours, or your mother’s illness. It wasn’t that at all. Your friend’s problem and your mother’s illness really concerned him: he carried them in his heart, because he had a big heart.

“One fine day I got up with a pimple on the tip of my nose. During the morning I met at least eighteen people who told me one after the other, without fail, that I had a pimple on my nose! At some point the Father passed by the place where I was working, but he said nothing, and shortly afterward someone brought me a tube of ointment ‘from the Father, for the pimple.’ “

2

He had a big heart which embraced all his sons. And also his daughters, although he maintained a distance of “5,000” or even “50,000 kilometers” from them. But if it was snowing and he knew two or three of the women from Villa Sacchetti had left early to go to the out-of-town wholesale markets, he would phone to ask whether “those daughters of mine put chains on the wheels of the car.” Monsignor Escrivá’s way of loving was not angelic or theoretical. It meshed with people’s small day-to-day needs.

When the women of the Work went to live permanently in Villa delle Rose, Monsignor Escrivá suggested they get a dog “to guard the house, especially at night time.” One morning they found the dog dead. There was no sign of violence, so they concluded it must have been poisoned. That same day they told Monsignor Escrivá.

“Don’t worry,” he told them, “but get another dog this very day.”

3

In the spring of 1974 the Italian government imposed some fuel restrictions. One was to restrict the use of cars on Sundays and

holidays to those whose plates ended in an odd or an even number, depending on whether the date was odd or even. Monsignor Escrivá immediately talked to Carmen Ramos and Marlies Kücking about it. He was concerned about the women who lived and worked in Albarossa, the catering wing of Cavabianca on the outskirts of Rome, who might find themselves cut off in an emergency since there were many of them and they had only one small van.

“Before Sunday you will need to see to it that these women have another vehicle. Make sure that the plate numbers of the two vehicles are alternate: one odd and the other even. We are poor, but when necessary we spend what we have to.”

4

Around this same time there were demonstrations and disturbances on the streets of Rome, and news of possible attacks by groups of political extremists. Monsignor Escrivá recommended closing windows on the ground floor, having sandbags ready in the garage, and not opening mailboxes.

“I trust our Lord completely, and I know nothing will happen to you. But I think we should use all the available means, humanly speaking, as well.”

5

Force the door open

He adopted security measures for all the centers throughout the world, even to the details of how bars on outside windows and doors could be made decorative.

In Villa Tevere, he ensured that the front door of the women’s house, which opened onto Via di Villa Sacchetti, was secured during the day with a heavy chain on the inside and always opened by two people, so that in case of a robbery or attack one would always be able to raise the alarm. He also had a loud bell installed next to the receptionist’s desk.

“This bell doesn’t need to go off outside but inside the house,” he explained, “because if anything happened, we would be the ones to come and help.”

All were common sense precautions not intended to make it difficult to go out but get in. Applying this to vocation, Monsignor Escrivá would say “the door is always open” to leave the Work, but to join, “I don’t make it easy: you have to push hard—to force the door open.”

After the Carnation Revolution

After the popular Carnation Revolution that began in 1974, Portugal went through a period of political turmoil, involving searches, requisitions, and confiscations. Some people of the Work lost their possessions, homes, and jobs. In these times of instability and fear, people were not only afraid but hungry. Monsignor Escrivá, in Venezuela at the time on his last catechetical journey, instructed two of his daughters, Mercedes Morado and Josefina Ranera, to go to Portugal “to help their sisters in need as far as possible, at least with their presence, serenity, morale, and affection.” On his return to Europe he stopped in Madrid to get direct news of the people of the Work in Portugal.

6

In 1955, the women of Villa Tevere took over the operation of the printing press, previously done by men. Monsignor Escrivá made several recommendations about the use of the machines and in particular called attention to the danger of the cutter. “Look, this contraption cuts through a stack of paper two inches thick like butter,” he told them. “Martha, please make a notice to warn people of the danger, and put it up where everyone can see it.”

He warned about this on several occasions, not ceasing until in 1970 they acquired a high-security cutter with a photo-electric sensor. “What a weight you’ve taken off my shoulders!” he said. “Thank God, because the hand of a daughter of mine is worth more than the best machine in the world.”

7

He was also constantly solicitous that the people who worked with the linotype machines should drink plenty of milk “to neutralize the effects of the lead vapors you breathe in there.”

8

One day Palmira Laguens, Annamaria Notari, Jutta Geiger, and other students of the Roman College were decorating the walls with borders in a new area of Villa Tevere called Il Ridotto. Monsignor Escrivá went to encourage them in their work. On leaving, he called two of them aside; he looked serious, rather sad. “My daughters,” he said, “sometimes you women are very hard. Don’t you have eyes in your heads? You need to have hearts. This sister of yours, Annamaria, is obviously losing weight, she looks like a skeleton, she’s very pale, and she has dark circles under her eyes. Is she ill? Has she lost her appetite? What’s the matter with her? Tell Chus,

9

or whichever doctor is at home now, to see her immediately and say whether she needs a tonic or she should start having a mid-morning snack. Do whatever is necessary to make this daughter of mine fit and healthy again!”

10

“What was the matter with Dora?”

Dora del Hoyo was a domestic worker who had been in Opus Dei since the 1940s. She had successfully done all kinds of work, hard and delicate, and was an expert in linens, ironing, and dry cleaning. When a laundry needed to be installed for a large house, be it Villa Sacchetti or Albarossa, Monsignor Escrivá saw to it that her opinion took precedence over the opinions of the architects and engineers. One evening in December 1973, Monsignor Escrivá had guests for dinner and Dora waited at table. Next morning he asked Mercedes Morado, “What was the matter with Dora last night?”

“Dora? Nothing, Father. I don’t think anything’s the matter with her.”

“Look, don’t just think: find out and tell me, please. Last night she looked awful. Something was wrong with her. Better not ask her directly, so she doesn’t realize I’m worried.”

Dora had a toothache. Monsignor Escrivá noticed this in the face of the woman even though he seemed attentive only to his guests.

11

Stealing a piece of heaven

He could put himself in other people’s shoes. Encarnita Ortega suffered from severe migraine, and Monsignor suffered as if he had migraine himself. On his insistence, Encarnita consulted specialists. After repeated visits to doctors and different methods of treatment with no success, he said finally, “We’ll just have to put up with them, and offer them up, my daughter. I think we’ve done all we could do—all your mother would have done.”

12

He often said, “In Opus Dei the sick are a treasure, for whom we don’t begrudge any effort.” If necessary, “I’d be capable of stealing a bit of heaven for a child of mind who is suffering, and I’m sure our Lord would not be cross with me!”

13

In the 1930s, when Josemaría Escrivá put together the points of

The Way

, he wrote the words “Children” and “the Sick” with capital initial letters. He explained, “The reason is that in little Children and in the Sick, a soul in love sees Him.”

14

Once, shortly before Christmas, José Luis Illanes, a talented and lively student from Andalusia, was in bed with a high temperature. Upset that José Luis could not share in the celebrations everyone was enjoying, he asked Marlies and Mercedes to get the catering staff to prepare “a little Christmas tree like the ones we’ve got in the house, but just a small one, covered with decorations and lots of chocolate figures. The fact is that one of my sons is ill…. I’ve got a tiny figure of Baby Jesus to take to his room. It breaks my heart to think that he has to spend these special family days in bed with a temperature.”

15

In October 1959, Mercedes Morado was told by her doctor that she needed an operation on her gall bladder. When Monsignor Escrivá heard this, he asked her to come to the dining room of Villa Vecchia with Encarnita. Monsignor Escrivá often met his daughters there for personal messages or short conversations.

“Mercedes,” he began, “I don’t know what you think. Of course we’ll do whatever you say, but I’m going to tell you what I think. What would you say if instead of having the operation here, in a hospital in Rome, you were to go to Madrid to get a second opinion and then, if they say the same, have the operation there?”

“But Father, why?” exclaimed Mercedes. “It would be tremendously expensive—not only the journey, but also more doctors!”

“Well, there are two main reasons. First of all because you don’t yet speak Italian properly, and a patient needs to explain to the doctor exactly what the matter is, where it hurts and all the symptoms, as well as understanding what the doctor says. And secondly, your parents live in Segovia, and they’ll want to be near you, naturally, during the days following the operation. If you’re in Madrid it will be a lot easier for them than if you have the operation here.”

16

At that time the financial situation in Villa Tevere was not very strong. But not only did she have the operation in Spain, she stayed there for months while convalescing.

For Monsignor Escrivá, this generosity was perfectly compatible with avoiding waste like leaving taps dripping or lights on in empty rooms, buying useless “bargains,” making lengthy but pointless telephone calls, and so on.

During a meeting one day in the sitting room of La Montagnola in Villa Sacchetti, the phone rang. Someone answered it and, after a couple of brief phrases, hung up. Monsignor Escrivá asked who it was.

“It was from the women’s center of the Work in Milan,” she replied. “I told them to call back later because we were in a meeting.”

“No, my daughter,” Monsignor Escrivá told her, “that wasn’t right. You can’t ignore a long distance call from another city. That’s not poverty, it’s irresponsible, because they weren’t telephoning you for a chat but to tell you something.”

17

Julia herself would never ask for anything

Julia Bustillo had come to Rome with the first group of women when the men were still living in the rented flat of Città Leonina. She was a pleasant, rather forthright woman, a Basque from Baracaldo, who got to know the Work in the 1940s as a cook in the first center of Opus Dei in Bilbao. She was now an elderly lady with a bun at the nape of her neck and never a hair out of place. For everybody in the Work, Julia was a real character, and not just part of the family but part of the very house.

One night in September 1965, Julia did not feel well and had to go to the bathroom. She did not turn the light on so as not to waken anyone. She felt her way along the corridor, but when she reached the stairs she missed a step and fell downstairs, hitting her head and breaking both wrists. A doctor was called, and by dawn she was in the hospital. Monsignor Escrivá was told when it was all over. Extremely concerned, he called a meeting of all the directors of the central advisory and, without mincing words, complained as a father. How could they not have realized that Julia herself would never ask for anything? A woman of nearly seventy should have all she needs in her room and not have to be walking around corridors and staircases at night. Then he asked, “When you called the doctor, did you call the priest too?”

“Well, no, we didn’t. We didn’t think.”

“My daughters, you have to love each other more, you have to love each other better! You worried about her body. Fine. But you didn’t worry about her soul.”

18

When the first Japanese women of Opus Dei came to live in Rome, Monsignor Escrivá insisted that as “women are like fragile porcelain there,” they should be treated with exquisite delicacy and helped “to adapt to the climate, food, language, and Western customs.” Thus: “As they are used to walking on carpets, for the first few days let them use slippers around the house until they get used to our hard floors.”

19

Another time he noticed that a European daughter of his who had lived in Africa for several years had prematurely aged skin. He said, “I don’t know much about these creams and things, but I’m sure there must be some kind of face cream that will revitalize her skin. Buy her some jars to take back to Nigeria with her.”

20

Bertita was a girl from Ecuador who had just arrived in Rome and was living in Villa Sacchetti, helping with the housework. Monsignor Escrivá knew she had had a deprived childhood, with much hardship and suffering. Now that she was living in a center of the Work, he wanted her to find all the love and joy she had lacked. Whenever a pretty package arrived, he would keep the colored ribbons “for my little daughter from Ecuador.” If they received a present of chocolates, he asked the administration to ensure “that Bertita gets one of the biggest ones,” even by “cheating” a little if necessary.

One morning Begoña Alvarez answered the house telephone and was surprised to hear Monsignor Escrivá asking about something quite unexpected. “Do you know if Bertita has any woolen vests?”

“Woolen vests? I don’t know, Father, I’ve no idea!”

“Well, find out, please, and tell me.”

Begoña lived in La Montagnola with the other directors of the advisory. She asked the person who would know, Blanca Fontan. In point of fact, Bertita did not have woolen vests.

“I thought as much,” said Monsignor Escrivá when she reported this. “It’s beginning to get cold in Rome, and this daughter of mine must feel it more than anyone else. Will you make sure that she gets herself a couple of woolen vests before the day is out? Nice soft wool that won’t scratch.”

21

In the summer of 1955, Encarnita Ortega was away from Rome. Monsignor Escrivá spoke to Helena Serrano and Tere Zumalde. “What do you think of maybe giving Encarnita a surprise by painting and decorating her office while she’s away? It’s so dark and shabby! Give it a bit of color, brighten it up, hang a few pictures and some other pleasant little surprise. My daughters, this isn’t a whim of the Father, it’s a small act of justice. When you joined the Work,

you found almost everything in place, but your older sisters, poor women, have been through all kinds of privations: they have lacked clothes, furniture, and basic comforts; they’ve suffered hunger and cold; they worked like pack donkeys to get the Work going. Isn’t it only fair that they should find something nice now? Will you do it? Of course you will, putting your hearts and souls into it.”

22

That same year he traveled a few times to Germany, where the people of the Work were “lifting the cross from the ground,” as they called beginning the apostolate in a new country. On the evening of August 22, Monsignor Escrivá went to Eigelstein, a residence for women students in Cologne, with Don Alvaro and another priest. They were unexpected, and could see the precariousness of the situation and enormous economic difficulties his daughters were having.

Monsignor Escrivá had words of affection and encouragement for each of them: Käthe Retz, Carmen Mouriz, Marlies Kücking, Tasia Alcalde, Pelancho Gaona, and Emilia Llamas. He asked Marlies about her friends, he spoke to Emilia in Italian so she did not forget it, and she told him how she managed to cope in German when they went shopping. He asked Käthe how her parents were, and encouraged Carmen and Pelancho to eat and sleep more, because “you don’t look too well, and you must take care of your body, which is the container of the soul.” He talked about Burgos, Tasia’s hometown. After the conversation, which lasted some time, he took a tour of the residence. At one point he asked, “Where do you wash the sheets and the clothes, yours and the residents’? Don’t you have a washing machine?”

There was embarrassed silence. This was something they would have preferred him not to notice. But he insisted on knowing how and where they did the washing, so Tasia explained, “There’s a machine provided for the use of everyone in this block.”

Monsignor Escrivá made no comment. He went into the oratory again. The walls had been neatly covered with fabric, but not even this embellishment could hide the dire poverty. He said to Don Alvaro, “Alvaro, will you please write to Rome and ask them to paint a nice triptych for the oratory of these daughters of mine.”

Before leaving, he gave them a couple of boxes of Swiss chocolates. “I bet you’d forgotten that such things as chocolates exist!” he said.

At a time when they were counting every lira in Rome, the students of the Roman College used to walk to their lectures because there was no money for bus fares; meat, wine, and coffee were luxury items, served only on the most solemn feast days. But Monsignor Escrivá was alive to “the small, prosaic needs of his children.” The day after his visit, two men from an appliance store arrived at the Eigelstein residence bringing a washing machine, a small spin dryer, and a trolley for transporting the clothes. Don Alvaro had bought these on behalf of Monsignor Escrivá.

23

A song in the laundry

Occasionally, on special days they showed a film in the main hall of Villa Tevere and Monsignor Escrivá watched it with the students of the Roman College. At other times, he watched films with his daughters. If it was a thriller or a mystery, he used to tease them by giving them false clues or threatening to tell them the ending. Now and again he used the loudspeaker for entertainment. One afternoon in 1954, he used it to call Julia and Rosalia, who were working in the laundry.

“Can you hear me? I have Madrid on the line. If you listen hard you can hear the conversation too.”

But what came over the loudspeaker was a song by the singer Agustin Lara. “When you come to Madrid, my darling, I will make you the Empress of Lavapies, / I will carpet the Gran Via with carnations, / and give you fine sherry to bathe in …” They heard Monsignor Escrivá laughing. There was no telephone call at all. “We got this record as a present, and I thought you’d like to hear it!”

24

“We’ve eaten three pianos”

During the 1950s, when the one musical instrument in many people’s homes was still the old gramophone, Monsignor Escrivá wanted a

piano for Villa Tevere so the men in the Roman College could enjoy themselves. Three times, friends gave them the money to buy one, but more urgent needs claimed the money first. Monsignor Escrivá used to say comically, “We’ve eaten three pianos!” One day the piano finally arrived. He brought his sons together in the sitting room and announced the news. A loud cheer went up. When they calmed down he said, “My sons, I can see you are delighted. I am too. But we were thinking—ahem—that maybe we should give the piano to … your sisters in the administration. What do you…?” He did not get to finish the question, as the cheers rose even more loudly.

Later, telling the women in Villa Sacchetti about it, he said, “We had no piano. Then suddenly we got the money for a piano but it turned out we needed it to pay for food … and that happened again and again. This is our blessed poverty! In the end we actually got a piano, and my sons have given it up, with enormous joy, without even having seen it. This is true affection in this family of ours!”

25

This was what he had told the American Joan McIntosh— “We are a Christian family and we really love each other!”

From the start, Monsignor Escrivá taught the members of his supernatural family to love God with the same heart with which they loved their parents, and to love their parents with the same heart with which they loved God. He called “Honor your father and mother” “the sweetest commandment” in Opus Dei.

One day in 1964 he called Begoña Mugica and Helena Serrano to the dining room in Villa Vecchia, though their respective jobs had nothing to do with each other.

Monsignor Escrivá showed them an old Castilian oil lamp. “If you get together, there’s a job here for both of you,” he said. “Begoña, try to clean this metal without destroying the patina on it; and you, Helena, see if you can find a way of changing the silk lining on the lampshades, because it’s worn out. An antique is one thing; dirt is quite another!”

That seemed all he wanted. But then he added, “Do you know that you are both going to Spain to do your annual course? Other people will be doing the same in due course, but you two are going to be the first.”

For people in Opus Dei the “annual course” was a break from ordinary work, a time spent together for three weeks or more, relaxing while studying, or studying while relaxing. In those years of economic hardship, they always did their annual courses near home, to avoid spending money on traveling. Begoña’s and Helena’s surprise showed in their faces. Monsignor Escrivá made the gesture of sealing his lips. “And now, mum’s the word. You don’t know a thing.”

They realized that exactly four years earlier, in 1960, their fathers had died in Spain, and neither had been able to be with their families then.

26

Each case was different. That same year, 1960, Mary Rivero’s father fell ill: he was an elderly man and was going through a bad time economically. When Monsignor Escrivá heard the circumstances of the case, he weighed what it would mean if Mary were to leave Rome and give up her post as central procurator. “My daughter, you know very well how difficult it is for me—and how it hurts me—to have to do without you here. It would be untrue to say that whoever takes your place will do the work as well as you. But you have to go to Bilbao and take care of your father: that’s only fair. We’ll be supporting you from here, and I’m sure you’ll do it very well! And if you put supernatural outlook and a lot of love into it, you’ll be helping us so that the work here won’t be weakened by your absence.”

27

He often encouraged his children to write their parents to tell them what they were doing, send them a photograph, and keep them up to date on the Work.

“Count on your parents,” he told them. “They have a right to feel that you love them. I love them very much, and I pray for them every day. Bring them closer to God. A good way of doing that is to bring them closer to the Work. How could anything we do be pleasing to God if we neglected the souls of those who have loved us most on earth? You owe them your life, the seed of the faith and an upbringing which has made your vocation possible. Love them and count on them.”

28

One day, looking at a small picture of St. Raphael in Villa Vecchia, he said to one of his Spanish daughters, “I really love this little picture. Do you know why? Well, because it’s the Archangel St. Raphael, it comes from Cordoba, and your mother sent it to us!”

29

“Our liabilities, which are blessed”

Carlos Cardona’s father was very ill, and Carlos, who lived in Villa Tevere, had gone to Gerona in Spain. He wrote to Monsignor Escrivá telling him of his father’s death, and in the letter said his parents’ house had deteriorated a lot due to dampness and was not very comfortable; the tiny pension his mother was going to receive as a widow would not be enough for her to move. When he got back to Rome, Monsignor Escrivá welcomed him and almost immediately began to speak about his domestic problem. “Carlitos, don’t you worry about your mother’s house. We’ll help her to move as soon as possible.”

From then until her death years later Mrs. Cardona received a monthly check to help her manage.

30

Needy or sick parents of some people of the Work, whom Monsignor Escrivá called “our liabilities, which are blessed,”

31

were always looked after.

Monsignor Escrivá said, “When your parents need anything which is not opposed to your vocation, we rush to give it to them, because they are a very beloved part of Opus Dei…. I have always impressed upon you that you should love your parents very much and I have stipulated that you should be with them when they are dying. You need to know how to bring them to the warmth of the Work, which is to bring them to God. And whenever necessary the Work will take care of them spiritually and materially too.”

32

Rosalia Lopez, a domestic worker, was one of the women closest to Monsignor Escrivá and served him at table every day at lunch and dinner. She had arrived in Rome in the early days. In 1964 she was going to Spain to spend a few days with her parents, who were

shepherds, simple, forthright people in the province of Burgos. A few days before she left, Monsignor Escrivá said to Begoña Alvarez, “You need to prepare Rosalia’s trip a little. Apart from her parents’ joy at having her visit them, I would like her to take something which they would like and which would be useful at the same time. I thought maybe you could buy a warm jacket for her mother and a shirt for her father. I’m sure they’d enjoy some Italian pasta and an Italian

panettone

. Wrap each gift beautifully, with great care.”

33

Another time it was Martina, an Italian, who was going to spend some days with her family in a little village in Umbria. Her mother was about to give birth to her ninth child, and Monsignor Escrivá wanted Martina to give the family a helping hand. He thought at once of sending a little present: “Some sweets that her little brothers and sisters will enjoy, and maybe a box of biscuits, but not Italian ones—find some foreign ones so it’s a novelty for the children.”

34

Small things, but things that showed his love and care.

One day Marichu Arellano, who lived in Villa Sacchetti, got a letter from her family saying that her father was not well. He had not yet been diagnosed, but they feared the worst. Mercedes Morado, director of the central advisory, waited a couple of days before telling Monsignor Escrivá, because he had known this family for years and was very fond of them. When she told him, he asked, “Does Marichu know yet?”

“Yes, Father. She’s known for the last two days.”

“Two days? And you’re only telling me today? Mercedes, you were wrong not to tell me immediately, because something like this, which affects a daughter of mine, affects me too. And all this time she’s been suffering, I could have given her a little bit of consolation. What’s more, we’ve lost two days when we could have been praying for them all.”

35

But Monsignor Escrivá did not confuse loving parents with emotional dependency. To the younger people in the Work he said, “It grieves me to say this, but so often it’s the family or friends or relatives who thoughtlessly oppose a vocation, because they don’t

understand, or they don’t want to understand, or they don’t want to receive light from God! They end up opposing all the noble things of a life dedicated to God. They even dare to test the vocation of their child, or of a sister, brother, friend or relative, and end up doing the work, the dirty work, of a procurer. And then they claim to be a Christian family. What a shame!”

36

Some verses from Cervantes

During his journeys to South America to speak of the teachings of the Church, a young man in the Work spoke to him of the difficulties his mother had raised, arguing that he should first “try other things, see more of life, taste human love so as to be sure, and then make his choice.” Monsignor Escrivá answered unhesitatingly. “Some verses by Cervantes come to mind, ‘Woman is made of glass, but better not try to see if she will break or not, because everything is possible.’ So better not try to see if you will break. Tell her to leave you in peace! Your mom is mistaken here. She ought not to want you to carry out experiments which would be an offense against God. If she doesn’t leave you alone, she will lose her own peace of mind, confuse her conscience and put her eternal life in jeopardy…. My son, love your mother a lot. Contradict her firmly, but kindly and good-humoredly, because in this she’s wrong, poor woman.”

37

On November 2, 1973 he had a visit from parents of a woman who lived in La Montagnola, a member of the central advisory. As soon as they exchanged greetings, the mother said, “Well, I was very curious to meet the person who was more powerful than I was— because I fought hard against my daughter’s vocation, but it was no use! You were the stronger, and she and you got your own way.”

“I’m sorry to contradict you,” Monsignor Escrivá said, “but it is our Lord who was the stronger, not me. If it were for my sake that your daughter were here, she could go whenever, right now if she wanted. Personally, I don’t need her at all. Not at all! And I didn’t call her: God called her. That is what a vocation is: a grace from

God, a divine calling. And it isn’t a sacrifice for parents if God calls their children. Nor is it a sacrifice for your children to follow our Lord. On the contrary, it’s a huge honor, a great glory, a sign of very special love which God has shown you at a particular moment, but which was in his mind from all eternity. I’d even dare to say this: it’s your own ‘fault,’ because you brought up your daughter in a Christian way. And so our Lord found the spadework done. Your daughter knows she has to be very grateful to you; she’s heard me say so hundreds of times, among other reasons because she owes ninety percent of her vocation to you.”

Next day, after a work session with the central advisory, Monsignor Escrivá said to the daughter in question, “Look here, I want you to write a letter to your mother on my behalf and ask her to forgive me for saying things so bluntly. Explain to her that I am from Aragon, so I like to speak clearly, face to face, without beating about the bush.”

38

“But Father,” she replied, “they were delighted! I could see my mother was pleased, and even

proud

. And my father was so moved when he left you that he asked to speak to a priest. And it’s been many, many years since he last received the sacraments.”

39

Appointments are burdens

Opus Dei does not remove anyone from his or her proper place. Members do their jobs according to their capacity, studies, availability, age, health, education, character, and suitability. There are no jobs of greater or less status. Directors are not appointed for life: this is a job they do for a time, then leave to do other things. No one is congratulated on being appointed director, nor does anyone complain when he or she ceases to be one. There will never be such a thing as an “owner-director.” Monsignor Escrivá said: “The owner-director does not exist. I have killed him off.” It goes without saying there are no grades, levels, social classes, or privileged groups in Opus Dei.

Lawyers are up-to-date in law, doctors study new diagnostic techniques, soldiers perfect their martial skills, cooks their skill in cooking, and business people try to balance their right to legitimate profits with service to society. When some priests of the Work were ordained bishops, Monsignor Escrivá told them, “When you get home, put all your ‘jewelry’ away in a drawer, because in our family no one is greater than anyone else. It is the same if someone is appointed a governor or a minister in his country: in the Work he continues to be loved as before, but he does not acquire any preeminence, nor does he have any special privilege. At home all these honors have no importance whatsoever. Is that quite clear?”

40

In October 1961 Encarnita Ortega left Rome after holding appointments in the government of the Work for almost twenty years. She returned to Spain, where she worked in other fields of apostolate, as well as working professionally in women’s fashion. Monsignor Escrivá’s words on parting were, “Your mission, the mission of someone who has been in the Work for a long time, is not to command or impose your opinion, but to keep quiet and let your good example do the shouting.”

41

He impressed on his spiritual children the importance of “humility and service” to prevent directors from falling into the trap of arrogance or complacency. He himself refused to let people help him on with the cardigan he wore at home over his cassock, or carry his suitcase when he was traveling. On going to bed at night, he insisted on carrying his own camomile tea. “I’ll carry it myself! What are my hands for?” Often he repeated Christ’s words, “I have not come to be served but to serve.”

42

“And the last one for you, boss”

One Sunday morning he called Mercedes Morado and two students from the Roman College who were working on the decoration of Villa Tevere. He wanted to discuss some aspects of their work. On the dining room table in Villa Vecchia was a box of

yemas de San

Leandro,

a sweet from Seville. After making suggestions about ornamental details, he opened the box and shared some sweets. He offered them to Mercedes Morado last, saying, “And the last one for you, boss, because those of us who give the orders should always be last.”

43

He made no distinctions between people or social classes. What made a job important for him was “the love of God with which it is done.” On one occasion he said, “If you asked me which I preferred, a daughter who was a professor at the Sorbonne or another who was washing dishes in the latest hospital you’ve started up out there, I really don’t know the answer! It would depend on how they each carried out their work, on the love of God they put into what they were doing. I’d very often envy the one who was washing dishes.”

44

He also said, “All souls are the same, because they are all made in the image and likeness of God. A university vice-chancellor, an ambassador, or a peasant all have the same rank before God. Except that the souls of simple people are often more beautiful, because you learn good manners by being in contact with well-mannered people. So it is that illiterate souls who speak and listen to God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Spirit, Our Lady, the Holy Angels, and St. Joseph, can become very delicate souls, really delightful ones. They possess divine knowledge which is the essence of wisdom, and know so many things that the learned of this earth do not know.”

45

Some women in the Work have housework as their profession. It is their responsibility that centers of Opus Dei be cozy, clean, cheerful family homes. Monsignor Escrivá sometimes called them “my little daughters.” He felt like “those mothers who are lost in admiration of the child they never expected to have.” In 1964 he told some domestic employees in the Work, “You have a special, outstanding place in the heart of this poor founder. I seldom use the word ‘founder,’ but I am doing so now deliberately. You deserve that special place, because you occupy it in the heart of God.”

46

Marlies Kücking and Mercedes Morado made a written note of his words. “Though not fully understanding the depth of what I was hearing,” Mercedes said, “I clearly realized it was something important in the life of the Work from the Father’s attitude and the emphasis he employed in speaking. It seemed to me the Father had just unveiled certain sentiments of his heart.”

He paid special attention to his favorite daughters. If the people in Villa Tevere were given some sweets and there were not enough to go around, he sent them to Villa Sacchetti “for the staff.” The first rooms to be air conditioned were the kitchen, the server, and the laundry. These rooms also had the most modern equipment. Monsignor Escrivá fostered the setting up of catering schools and colleges in many countries to provide people in the catering profession with scientific and technical knowledge of the highest standard. He also made sure these schools and colleges promoted the image of caterers by giving them education that took in all aspects of the person: spiritual, professional, cultural, aesthetic, social, apostolic, and physical. He also encouraged them to stand up for their rights as citizens.

One day in 1962 in La Montagnola they were installing furniture and putting the finishing touches to the decoration. They wanted Monsignor Escrivá’s opinion on a particular ornament to be placed over the door. They needed a small ladder, and two domestic employees brought one in. Monsignor Escrivá thanked them. When they had left, his expression and tone of voice changed, and he said to the women, “Listen carefully. In the Work all of you are servants of each other. You must never let yourselves be served! You, as directors, ought to be the first in coming forward to do the most difficult, demanding, and unpleasant tasks. That’s where you have to lead!”

47

“Today it’s my turn to serve”

On March 19, 1959, feast of St. Joseph, the patron of Opus Dei, Monsignor Escrivá came to the servery when the dishes were ready for lunch. Picking one up, he took it into the dining room. Seeing

Julia Bustillo, the eldest person there, he went to her and held the dish for her to help herself.

“In the house at Nazareth everyone served each other,” he said. “Today it’s my turn to serve!”

48

Some days later he said to the directors in La Montagnola, “In the Work we don’t have ‘servants.’ Different people do different jobs. We each do our own job and all of us serve God, who is our only Lord. It would be a good idea if sometimes (and it doesn’t need to be a special day or a feast day, but an ordinary day) you serve at table for those who normally serve you because it’s their job.”

49

During her long stay in Rome, Encarnita Ortega visited Cardinal Tedeschini on several occasions and heard him pay tribute to Opus Dei and its founder. He said that of all the people he knew, Monsignor Escrivá was the most attentive to God’s plans and carried them out the soonest. “He is the holiest man I know,” said the cardinal, “maybe the only saint I know.” Then he made another comment: “The biggest miracle achieved by the Father in this Work entrusted to him by God is the vocation of those women who work in the administrations and feel so proud of serving all their lives that they wouldn’t change places with a princess.”

50

In June 1967, Monsignor Escrivá reminded those who had completed their doctorates at the Roman College of the Holy Cross and were leaving, “We don’t create supermen here. You’re not going out there to give orders, still less to interfere! You’re going to serve. You’re going to be the last of all, putting your hearts on the floor as soft carpets for the others to walk on.”

51

The last bedspread

Although people of the Work began to live in Villa Tevere in 1949, they had to share their daily lives with the noise and confusion of builders, plumbers, electricians, and painters for more than ten years. And it was not until 1964 that some details such as bedspreads

were in place. Until then, the beds, of which there were more than 200, were simply covered with blankets. Monsignor Escrivá’s blanket was very worn, with a faded green and brown pattern.

In 1956 they received an unexpected donation, and the women thought of using it to buy material for making bedspreads, but in the end the money had to be used for other, more pressing needs. Some years later they proposed to Monsignor Escrivá that they should get the material for bedspreads little by little. Admittedly, they argued, they were nonessential, but they would complete the bedrooms and give them a cozier, more homelike look. Monsignor Escrivá consented but made them reverse the order they had suggested; they should begin with the bedspreads of his daughters on the domestic staff, followed by those of the teachers and students of the Roman College. Next it would be the turn of the members of the general council. And last of all: “Make mine when everyone else has theirs. I want to be the last one.”

One Sunday in March 1964 the house telephone rang in Mercedes Morado’s office. It was Monsignor Escrivá. “Thank you, my daughter, and God bless you!” he greeted her. “What a surprise I had the other day when I came into my room! I thought I’d gone into the wrong room by mistake. Then I said to myself, ‘Long live luxury and its maker! Josemaría, you’re getting rich!’ Mercedes, my child, when time has gone by and I’m no longer in this world, you will tell your sisters this little story. Why did the Father want to be the last to have a bedspread? For two reasons. First of all, out of the great love I have for my daughters: I wanted you to be first. And secondly, out of poverty. Not having a bedspread simply doesn’t matter! The Work is thirty-six years old. And now, for the first time in thirty-six years, I have a bedspread.”

52

To be of use, you must serve

On June 25, 1975, the day before he died, he spoke to Rolf Thomas about service. He referred to passages in the Gospels where Jesus tells his disciples, “he who is first shall be last,” “do not seek the first

places at table,” “I am in the midst of you as one who serves, because I have not come to be served, but to serve.” He contrasted this strongly with “the climate of pride which is spread all over nowadays, and which makes people reject anything they consider demeaning.” “As a result of your efforts to give life back its Christian meaning,” he said, “many people will wonder, with great joy, about whether they can give themselves to a life of service: to serve everyone, for the love of God. And they will see it as what in fact it is: a great privilege! From all parts of the globe the finest souls will come to the Work, the most spiritual and cultured ones, those who wish above all to identify themselves with Jesus Christ, and they’ll ask for admission to Opus Dei, with a resolute vocation to serve.”

53

Soon afterward, young women graduates from universities and technical colleges in several countries asked to be admitted to Opus Dei, expressing a preference to dedicate themselves to housekeeping tasks. It was a direct challenge to an individualistic, stony-hearted civilization where nurses, teachers, and housewives were considered anachronisms.

Monsignor Escrivá transmitted a code of conduct: para servir, servir

—“to be of use, you must serve.” To be of service, one had to make oneself available with “the healthy psychological attitude of always thinking about others.” And this was service rendered to God himself.

While Monsignor Escrivá regularly recited Psalm 2, which says “serve the Lord with fear” (servite Domino in timore

), after a time he also began to say to his children a verse from Psalm 99, “serve the Lord with gladness” (servite Domino in laetitia

). By directing to the Lord what we do for our fellow men, the act of service is done with the gladness of freedom.

Monsignor Escrivá confronts a head

of government

In June 1974, Monsignor Escrivá had a get-together with several thousand people in the congress center of General San Martin

in Buenos Aires, Argentina. A young man spoke up. “I’m in the Work. My mother, who is almost my whole family, because I don’t have a father—”

Monsignor Escrivá interrupted. “What do you mean, you don’t have a father!” He held up his hands and counted on his fingers. “One, in heaven; another, in heaven; and me: you’ve got three altogether!”

“Well,” said the young man promptly, “as today is Father’s Day: congratulations, Father! Anyway, my mother is very happy about my vocation. But sometimes she worries about what will become of me when I’m old. She says I won’t have a family. She’s here beside me, Father—here she is. I want you to explain to her that we do have a family and love each other a lot.”

“Yes,” agreed Monsignor Escrivá, “sit down. Once, many years ago, a man in Opus Dei in a certain country was not in agreement with the way the head of government acted, and had written some things in a newspaper which offended this person. And this very powerful person got angry and declared that the Opus Dei man had no family. So I, who do have a family, immediately asked for an audience, and they could not deny me one.”

Monsignor Escrivá was referring to an episode that happened in Spain. Rafael Calvo had written an article attacking the Franco regime. The authorities reacted very harshly, and Calvo had to go into exile. Among other insults printed about him was one calling him “a person with no family.” Monsignor Escrivá went to Spain immediately and requested an audience with Franco. In it he said Calvo did have a supernatural family, the Work, and Monsignor Escrivá considered himself his father.

Franco inquired, “What if he goes to jail?”

Monsignor Escrivá answered, “I will respect the decisions of the judiciary; but if he goes to jail, no one can stop me from providing my son with all the spiritual and material assistance he might need.”

He repeated the same thing to Admiral Carrero Blanco, Franco’s right-hand man, who admitted that the founder of Opus Dei was right.

Monsignor Escrivá went on, “… And I said to him, ‘You

have no family, he has mine! You

have no home, he has my home!’ He said he was sorry.”

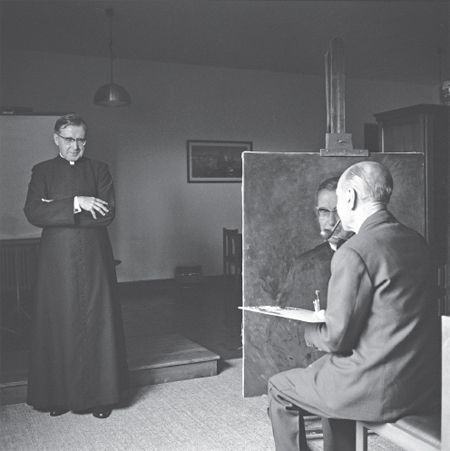

Under the brush of portrait painter Luis Mosquera at Molinoviejo in September 1966.

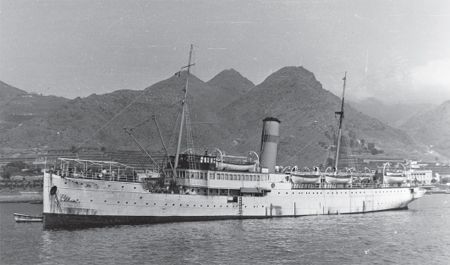

The J.J. Sister

, in which St. Josemaría traveled from Barcelona to Genoa in 1946. Photo taken in the port of Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Canary Islands. The ship was scrapped in 1974.

Above: Buildings at Villa Tevere, Rome, under construction in 1950.

Above right: Aunt Carmen with her boxer, Chato, during Christmas 1956.

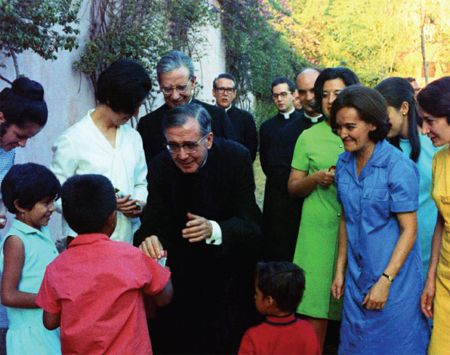

Give-and-take with young men in a get-together in Buenos Aires, Argentina in 1974.

Meeting university students and professional women in Rome in the early 1970s.

Relaxing in 1964. In the left foreground, Bernard Villegas, from the Philippines.

With workers and farmers in Jaltepec, Mexico in 1970.

Meeting families at Montefalco, Mexico in 1970.

The best place to live and the best place to die

Monsignor Escrivá then addressed the mother of the boy who had spoken. “Now you know your son has a family and a home, and that he will die surrounded by his brothers, with immense affection. Happy to live and happy to die! Unafraid of life and unafraid of death! Let’s see who can say that out there! Unafraid of life and unafraid of death! The best place to live and the best place to die: in Opus Dei!”

He paused, threw his head back slightly and closed his eyes. He took a deep breath and exclaimed with all his heart, “How very well off we are, my children!”

54

“I would have willingly got down on my hands and knees”

In February 1950, Don Alvaro fell ill with acute appendicitis and liver problems. Doctor Faelli recommended an operation. Monsignor Escrivá tried to cheer him up by telling him cheerful stories. When he saw how bad the pain was, he began to improvise a funny dance. Don Alvaro and another man in the room started to laugh, which was exactly what Monsignor Escrivá wanted: “I had to do what I could to lessen his pain. From a spiritual point of view, although he was offering up everything with great supernatural vision, I thought our Lord would like him to forget about his pain, so I danced. I would have willingly got down on my hands and knees, whatever, moved by the wonderful reality that we are never really alone: God does not abandon us and neither do our brothers and sisters.”

55

One morning in December 1955, Monsignor Escrivá arrived home after praying beside the body of Ignacio Salord, a young student of the Roman College. He paused for a moment to talk with the girls on telephone duty, who saw that his eyes were red and swollen with crying. “He died as he lived,” said Monsignor Escrivá. “He knew exactly what was happening, that he was dying. He wished to make a general confession of his whole life. I’d say he didn’t need to. Anyway he did!”

56

In October 1960 three young people in the Work were killed in a car crash. A few days later Monsignor Escrivá said to one of his sons, Gumersindo Sanchez, “I got the news late, because I was on my way to France. When I heard it, I could not control myself, and I cried like a child—because I’m a mangy donkey and sometimes I drag the cross reluctantly.”

57

In the early hours of December 11, 1961 Armando Serrano died. He had lived and worked close to Monsignor Escrivá for a long time; among other things, he had been the driver on long car journeys. Monsignor Escrivá was so upset he could not eat break fast but had to leave the dining room in tears and go to the oratory. This was repeated two or three times, and on one of his hasty exits he met two of his daughters. He put his handkerchief in the pocket of his cassock, but could not hide his distress. “This son of mine is dead … Armando …” he said. “Go and tell the others so they can pray for him.”

58

An accident on the island of Guadeloupe

One morning in March 1968 Monsignor Escrivá had a meeting with the women directors of Opus Dei who had come to Rome from different countries for a special course. He entered the sitting room of La Montagnola at ten sharp. As soon as he sat down, he told them sad news: Vladimiro Vince, a Croatian priest of Opus Dei, had been killed in an air crash on the island of Guade loupe. Vlado Vince had met the Work as a refugee exiled in Italy during the war. He had translated The Way

into Croatian.

“I have been to the tabernacle to complain—lovingly, but I did complain—because I find it hard to understand how our Lord, having so few friends in this world, can take those who could serve him, when they are so badly needed! But then, as always, I end up accepting the will of God and saying: Fiat, adimpleatur

—May the most just and most loveable will of God be done, be fulfilled, be praised and eternally exalted above all things. Amen. Amen.”

His voice cracked and he swallowed. Standing up suddenly, he apologized: “I can’t go on speaking to you … Forgive me, my daughters.” And he left the room.

At the same time the next day he returned to the sitting room, looking quite different, even happy. He told them what he had just heard: two or three people of the Work, one of them a priest, had flown from Venezuela to Guadeloupe in an aircraft chartered by Air France for relatives and friends of those in the crash. Miguel Angel Madurga had also gone from Rome, sent by Monsignor Escrivá. The crash site was chaotic: bits of the aircraft, dead bodies, luggage strewn about, and the smell of death. The relatives had come to identify the dead, but one by one retreated to their plane, appalled at the scene. The people of Opus Dei kept searching determinedly until they found some personal belongings of Vladimiro. (Later they sent these to Croatia where his mother was still living, together with a photograph album.) While two continued the search, the priest prayed successive responsories for the dead and at a nearby chapel celebrated several Masses for the souls of those killed.

Monsignor Escrivá concluded his account in La Montagnola by saying, “Together with this tremendous sorrow, God has given me the consolation, the joy, of experiencing once again the fact that we are a family and love each other dearly: your brothers have done more for Wlado than husbands did for their wives, more than fathers for their sons. They have done what others, even actual relatives, did not have the courage to do. Always practice that blessed fraternity— heroically, if necessary.”

59

Sofia, Aunt Carmen

In May 1972 Mercedes Morado told Monsignor Escrivá that Sofia Varvaro, a young Italian, had been diagnosed with cancer. The doctors thought she had only a few months to live. Monsignor Escrivá said he wanted to go and see her immediately.

“Father, Sofia is living in Villino Prati, in Aunt Carmen’s house,” they told him. “In fact, she’s in the same room Aunt Carmen was in when she died.”

“Aunt Carmen” was Carmen Escrivá de Balaguer, Mon signor Escrivá’s sister. She had united her whole life and heart to Opus Dei, though she had never actually belonged to the Work. She looked after the domestic administration of centers before there were any women in the Work and put all her affection at the service of Opus Dei. A foundation stone in the history of the Work, after her death on June 20, 1957 she was buried in Villa Tevere in the crypt.

Her little apartment was at 276 Via degli Scipioni. “You know, I said I never wanted to go back to that house again,” Monsignor Escrivá said now, “and I’ve never been back since then. It holds so many memories! But a daughter is more than a sister. I can’t let Sofia leave us without going to see her and saying some words of consolation.”

A few days later he went to Villino Prati with Father Javier Echevarria. Teresa Acerbis and Itziar Zumalde were waiting for them. He started talking to Sofia before he had even entered her room. “Sofia, mia figlia!”

When he got to the room, he gave her a holy picture of the Blessed Trinity; on the back he had written a short prayer in big, bold letters.

“Shall I read you what it says?” he asked. “Would you like to say it with me? ‘My Lord and my God, into your hands I abandon everything, past, present, and future: big and little, great and small, temporal and eternal.’”

He encouraged her to be cheerful, simple as a child, and let herself be cared for, to take painkillers when she needed them, and to pray for her cure.

“Because there are still very few of you in Italy, and so much apostolate to be done,” he explained. “It would be too easy to go to Paradise. There’s still a lot of work to be done here! Although for us, the most important work is doing God’s will in everything.”

“Father,” she confided, “when they first told me what I had, my reaction was fear. But not fear of suffering or death—fear because I’m a very ordinary person, worth very little, and I don’t want to go to purgatory!”

“How about that! She doesn’t want to go to purgatory! You shan’t go, my daughter. Don’t be afraid, because our Lord is with you. Besides, that’s what everybody in Opus Dei is—ordinary! Our Lord has chosen us and he loves us precisely because we’re ordinary people. And you have to pray to get better because, just as you are, we need you! You have to help us a lot. Now I feel stronger because I’m relying on you. You can rely on me, and don’t be afraid! But if our Lord wants you up there, you’ll have to help us even more from heaven.”

Monsignor Escrivá followed the progress of Sofia’s disease closely. He urged the people looking after her to do all they could for her, with loving care; that they should be “more than a mother or a sister” to her. He told them not to leave her alone, and to help her to say the prayers and fulfill the other norms of piety that everyone in Opus Dei does every day; and to give her painkillers “so this daughter of mine does not suffer unnecessarily.”

He went to visit her again at a private hospital in Rome when she had gotten worse. Before going into her room, he said to Teresa and Itziar, “She mustn’t realize how we are suffering for her. How long will the doctor let us stay so as not to tire her? Well, when the time is up, if I forget, tell me: I’ll only stay as long as the doctor allows.”

He went in with Father Javier Echevarria and sat beside the bed. He spoke softly and encouragingly to Sofia about spiritual matters. Because he knew the value of suffering, he asked her to offer up her pain and physical difficulties “for the Church, for priests, and for the Pope.”

“Sofia,” he asked her, “will you join me in the intentions of my Mass?”

“But, Father, I’m here in bed. I can’t go to Mass any more.”

“My daughter, now you are a constant Mass! And to morrow, when I say Mass, I will place you on the paten.”

Shortly after this, Sofia said she was getting tired. Monsignor Escrivá made the sign of the cross on her forehead and said good-bye.

On December 24, while chatting with a group of Italian women of the Work, he asked, “How is Sofia doing? Every day when I get to the offertory of the Mass, I place all my sons and daughters who are ill or troubled on the paten.”

Sofia was dying. Toward the end, when her caregivers were praying the litany of the Rosary, at the invocation “Gate of heaven,”

Ianua coeli

, she smiled and said “That’s my one.” She died on December 26. Next day, Monsignor Escrivá went to Villa delle Rose in Castelgandolfo as had been planned. As soon as he entered the sitting room he said, “As you know, my daughters, there’s been a lot of coming and going recently. Your sisters are starting the Work in Nigeria, a few days ago I blessed another who should arrive in Australia today, and yesterday … this other daughter of mine left us to go to heaven.”

60

There was indeed a lot of coming and going. That same month, December 1972, Father José María Hernandez de Garnica, a civil engineer and one of the first three priests of Opus Dei, died in Barcelona. His nickname was Chiqui. Monsignor Escrivá had first met him in the 1930s when setting up the students’ residence in Ferraz Street in Madrid. Seeing him come in “dressed like a dandy,” Monsignor Escrivá gave him a hammer and nails, saying, “Come on, Chiqui, get up that ladder and help me put these nails in.”

How much had happened since then! So many apostolic journeys, so much coming and going, helping to establish the Work in half of Europe! So many loving memories!

In Barcelona in October 1972, at a get-together in the Brafa gymnasium, he confessed to those present that although he was delighted to be there, he had to leave. “A sick person is expecting me,” he said. “And I have no right to make a sick person wait—he is always Christ…. He needs his father and mother. And I am both father and mother to him.”

After visiting Father José María, he said to his sons, “I have been with a brother of yours today. I’m having to make a tremendous effort not to cry, because I love you with all my heart…. I hadn’t seen him for a few months. And now I think he looks like a corpse already. He has worked hard and with a lot of love. Maybe our Lord has already decided to give him the glory of heaven.”

61

When Monsignor Escrivá got back to Rome, he had in mind the aspiration

ut in gratiarum semper actione mane amus!

(“that we may always remain in the act of thanks giving”) from an old liturgical prayer. He wrote it in his diary as a “password” for the New Year, 1973, using an exclamation point to emphasize his gratitude, for as he said, echoing St. Paul, “Everything helps to secure the good of those who love God”—

omnia in bonum!

62

A box of crystallized fruit

In May 1975, after going to see the construction underway in Torreciudad, then almost completed, Monsignor Escrivá received a visit from the lord mayor and a councillor of Barbastro. After they left, Father Javier Echevarria and Father Florencio Sanchez Bella came in. They had sad news: Salvador Canals, nicknamed “Babo,” another of the older people in the Work, had just died. It was he who had gone to Rome with Jose Orlandis to pave the way for setting up the Work there.

Monsignor Escrivá began to cry openly. He prayed a responsory for the dead, interrupted by sobbing. Then, weeping silently, he went to one of the armchairs near the big window overlooking the esplanade of Torreciudad. The others sat around him quietly, respecting his prayerful sorrow. He prayed and remembered. After a while, he said, “I love all of you just the same—all of you—but you have to realize that I’ve lived through so much with Babo … so many years! It’s only natural his death should affect me more. It’s a hard blow, even though I knew Babo was dying when I left Rome. I even left everything ready—didn’t I, Alvaro?—so that his funeral could be celebrated in Tiburtino.

“I went to see him in hospital just a few days before coming here. I wanted to take him some sweets he liked, but I couldn’t remember what they were. I asked one of my sons who works in Villa Tevere to find out from the people he’d been living with … they said it was crystallized fruit, and bought a small box of them. Afterwards I had a sudden thought, and I called the women in the administration

in Villa Sacchetti, and asked them to go to a sweet shop and get a much bigger box, with bigger fruit, and they brought one right away. Alvaro and I went to the hospital. You can’t imagine how happy Babo looked to see us. He accepted the box, opened it, and offered us some. Alvaro and I took a small piece each. He looked at the fruits, and chose a really big fat pear. I was delighted! I thought: ‘Goodness, what if I’d brought the little box!’ Besides, like a mother, when I saw him eating it … I got hopeful. But when we left his room, the doctor dashed all our hopes; he said his heart was in a very bad state.”

Monsignor Escrivá took out his handkerchief, took his glasses off and dried his eyes. Night had fallen. Everyone was silent. Looking from one solemn face to the next, he stopped at the architect, César Ortiz-Echagüe, and exclaimed, “My son, Opus Dei is the best place to live and the best place to die. I assure you that it’s worthwhile!”

63