The AP U.S. Government and Politics Exam is a two-part test. The chart below illustrates the test’s structure.

There are several types of multiple-choice questions, which we’ll get into in Chapter 1, but they all pull from the five major topics of the AP U.S. Government and Politics course. Not all subjects are tested equally; the following list is a breakdown of how they appear in the newly released 2018–2019 sample test:

|

Subject |

Percent of Questions |

Covered in Chapter # |

|

Foundations of American Democracy |

12 to 20 |

Chapter 4: The Constitutional Underpinnings |

|

Interaction Among Branches of Government |

20 to 30 |

Chapter 8: Institutions of Government Chapter 9: Public Policy |

|

Civil Liberties and Civil Rights |

15 to 20 |

Chapter 10: Civil Rights and Civil Liberties |

|

American Political Ideologies and Beliefs |

10 to 18 |

Chapter 5: Public Opinion and the Media |

|

Political Participation |

20 to 30 |

Chapter 6: Linkage Institutions Chapter 7: Elections |

There are a wide variety of new questions on the exam that expect you to be able to analyze data, get to the heart of short reading passages and quotes, and to compare two distinct thoughts. Don’t be thrown; these questions tend to boil down to the dynamics of how government operates within a political environment. For example, you may be asked how interest groups attempt to influence policy making in Congress and the bureaucracy or how the president attempts to influence Congress through public opinion. The test writers want to know whether you understand the general principles that guide U.S. government and the making of public policy.

In addition to the multiple-choice questions, there are four mandatory free-response questions. You’ll have a total of 100 minutes to answer all of them. You should spend approximately 25 minutes per question, but be aware that you must manage your own time. Additional time spent on one question will reduce the time that you have left to answer the others. Writing more than is necessary to answer the question will not earn you extra points.

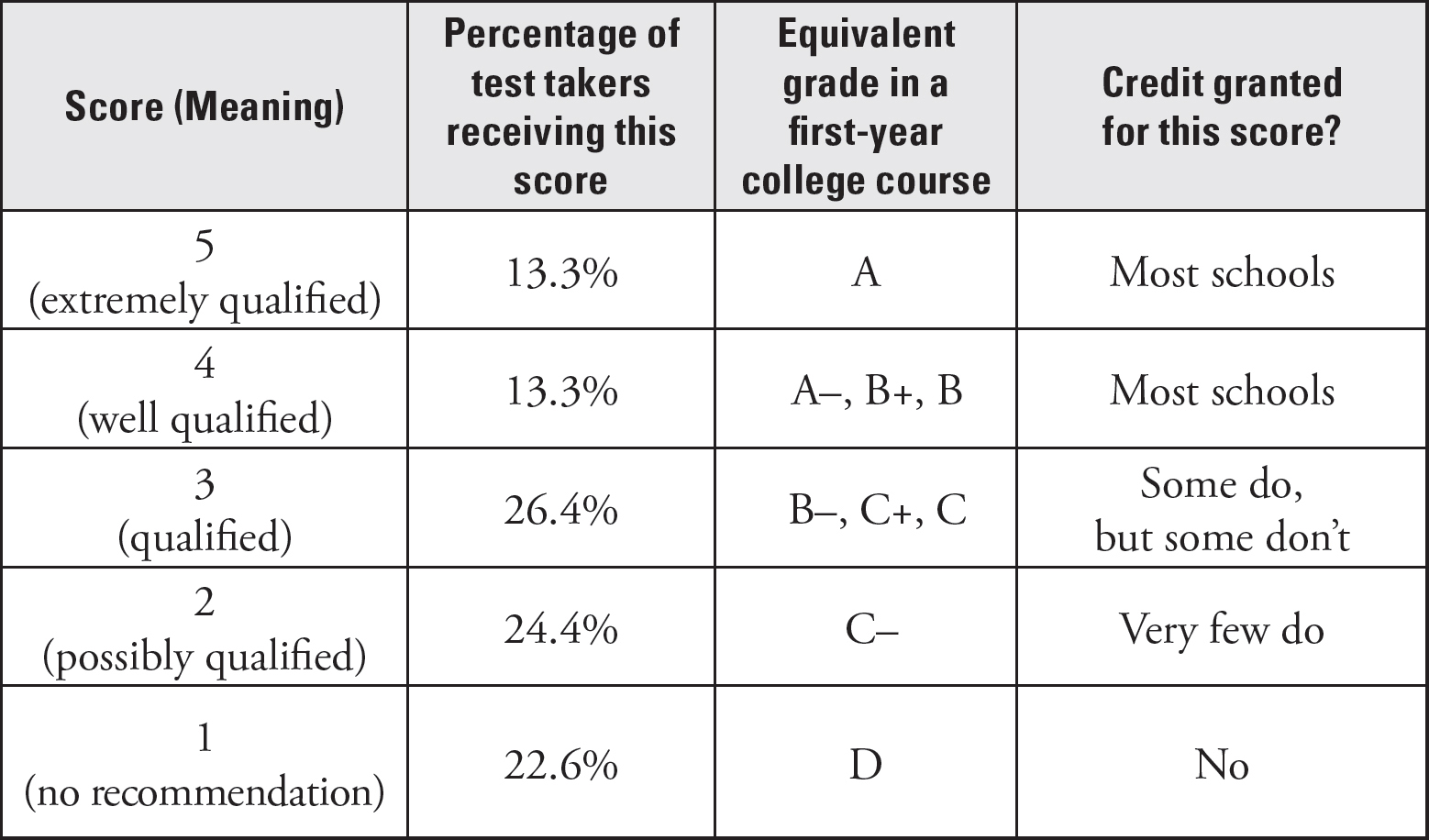

The graders assign each of your free-response answers a numerical score. Weighing the average on the free responses and the score on the multiple-choice questions each as 50%, the graders create a final score from a low of 1 to a high of 5. The chart below tells you what that final score means.

The data above is from the College Board website and based on the May 2018 test administration.

To score your multiple-choice questions, award yourself one point for every correct answer, regardless of whether you guessed the answer or not. (You shouldn’t have left any blanks, but if you did, they are worth nothing.)

Of course, if you follow our advice for how to write a good free-response essay, you could score higher on the free-response section than on the multiple-choice section and thus potentially increase your final score by one point.

As mentioned earlier, questions on the exam fall into five main units:

Foundations of American Democracy

Interaction Among Branches of Government

Civil Liberties and Civil Rights

American Political Ideologies and Beliefs

Political Participation

Here are some key topics that fall into each of these categories:

|

Foundations of American Democracy |

|

|

Interaction Among Branches of Government |

|

|

Civil Liberties and Civil Rights |

|

|

American Political Ideologies and Beliefs |

|

|

Political Participation |

|

As you can see, the primary focus of the test is the nuts and bolts of the federal government. The test also emphasizes political activity—the factors that influence individual political beliefs, the conditions that determine how and why people vote, and the process by which groups form and attempt to influence the government. Be aware that the test is always changing—especially for the 2019 iteration, so keep an eye on every area, such as constitutional issues and civil rights, which are very important for providing context to the new scenario-based questions.

One thing the course now expects from students is that they’ve learned the major details of fifteen different Supreme Court cases and that they are familiar with the ideas behind nine foundational documents. We touch on and reference these in the Part V content review, but you’ll definitely want to go above-and-beyond in familiarizing yourself with the following:

Marbury v. Madison

McCulloch v. Maryland

Schenck v. United States

Brown v. Board of Education

Baker v. Carr

Engel v. Vitale

Gideon v. Wainwright

Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District

New York Times Co. v. United States

Wisconsin v. Yoder

Roe v. Wade

Shaw v. Reno

United States v. Lopez

McDonald v. Chicago

Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission

The Declaration of Independence

The Articles of Confederation

The Constitution of the United States

The Federalist Papers Nos. 10, 51, 70, and 78

Brutus No. 1

“Letter from a Birmingham Jail”

While the primary sources listed above are the only ones that you’ll be required to know for the exam, you should take the opportunity to widen your familiarity with other documents.

Reading political articles in newspapers and magazines, particularly those that present accompanying information in visual formats, can be helpful when preparing for the Quantitative Analysis questions. The Argument Essay in Section II allows you to cite from other sources, and the SCOTUS Comparison question will refer to lesser-known cases (although it will provide you with all the necessary facts).

If you do your own reading—and we highly recommend it!—make sure that you take into account the credibility of your sources. If you intend to reference anything on the test, make sure these other texts are both credible and reliable. That is, make sure they’ve been fact-checked and that they are both well-sourced and up-to-date.

Different colleges use AP exams in different ways, so it is important that you visit a particular college’s website in order to determine how it accepts AP exam scores. The three items below represent the main ways in which AP exam scores can be used.

College Credit. Some colleges will give you college credit if you receive a high score on an AP exam. These credits count toward your graduation requirements, meaning that you can take fewer courses while in college. Given the cost of college, this could be quite a benefit, indeed.

Satisfy Requirements. Some colleges will allow you to “place out” of certain requirements if you do well on an AP exam, even if they do not give you actual college credits. For example, you might not need to take an introductory-level course, or perhaps you might not need to take a class in a certain discipline at all.

Admissions Boost. Even if your AP exam will not result in college credit or even allow you to place out of certain courses, most colleges will respect your decision to push yourself by taking an AP course or, even, an AP exam outside of a course. A high score on an AP exam shows mastery of more difficult content than is typically taught in many high school courses, and colleges may take that into account during the admissions process.

There are many resources available to help you improve your score on the AP U.S. Government and Politics Exam, not the least of which are your teachers. If you are taking an AP course, you may be able to get extra attention from your teacher, such as feedback on your essays. If you are not in an AP course, you can reach out to a teacher who teaches AP U.S. Government and Politics to ask if he or she will review your essays or otherwise help you master the content.

Another wonderful resource is AP Students, the official website of the AP exams. The scope of the information available on this site is quite broad and includes the following:

a course description, which includes further details on what content is covered by the exam

sample questions from the AP U.S. Government and Politics Exam

free-response question prompts and multiple-choice questions from previous years

The AP Students home page address is: https://apstudent.collegeboard.org/home.

Finally, The Princeton Review offers tutoring, small group instruction, and admissions counseling. Our expert instructors can help you refine your strategic approach and enhance your content knowledge. For more information, call 1-800-2REVIEW.

In Part I, you identified some areas of potential improvement. Let’s now delve further into your performance on Practice Test 1, with the goal of developing a study plan appropriate to your needs and time commitment.

Read the answers and explanations associated with the multiple-choice questions (starting at this page). After you have done so, respond to the following questions:

What are your overall goals for using this book?

Review the topic chart on this page. Next to each topic, indicate your rank of the topic as follows: “1” means “I need a lot of work on this,” “2” means “I need to beef up my knowledge,” and “3” means “I know this topic well.”

How many days/weeks/months away is your exam?

What time of day is your best, most focused study time?

How much time per day/week/month will you devote to preparing for your exam?

When will you do this preparation? (Be as specific as possible: Mondays and Wednesdays from 3:00 P.M. to 4:00 P.M., for example)

Based on the answers above, will you focus on strategy (Part IV) or content (Part V) or both?