9

A Historical Figure?

Before continuing with our investigation in the area of Britain that once comprised the adjacent kingdoms of Gwynedd and Powys, we need to directly appraise the case for Arthur’s existence. In the first chapter I said that even before I began my search for his final resting place, I had compelling reason to believe King Arthur had been a historical figure. It is time to elucidate. I have left it until now, because to appreciate my reasoning requires knowing something about the period in which Arthur is said to have lived; for example, the Roman occupation of Britain, the fall of the Western Empire, and the political and military upheavals in both Europe and the British Isles during the fifth century. We would also need to have examined the Anglo-Saxons and the Celts, the division of Britain into separate kingdoms, where these kingdoms were, who ruled them, and so forth. By the time we got round to considering evidence specifically concerning Arthur himself, we would be halfway through the book. Instead, I have now covered such relevant background material while recounting my search for the man behind the legend, just as it occurred. Furthermore, we have also explored the various themes within the Arthurian saga, discovering how, when, and why they emerged, preparing us to address the principal argument against King Arthur as a historical figure. So before presenting the case for him having been a real living person, let’s evaluate the case for the opposition.

The way I see it, the essential reason most skeptics refuse to believe King Arthur could possibly have existed is that the tales about him are just too unbelievable. In which case, they would argue, why bother searching for any truth behind the Arthurian legend? Consequently, merely to associate your name with such an investigation is enough to prompt scorn in academic circles, which is why many historians, archaeologists, and literary scholars tend to steer clear of the subject altogether. (Indeed, this is one of the main reasons that the true origins of the legend remained uncovered for so long.) The skepticism is quite understandable. Initially, the story of King Arthur seems completely fictitious. It includes mystical items, such as the Holy Grail, Excalibur, and the sword in the stone, and fabulous themes, such as Avalon, the round table, and Camelot; and there are mythical beings, such as wizards, water nymphs, and dragons. However, one by one, we have seen these seemingly fanciful elements removed as a reasonable argument against Arthur’s existence. Often we have found such themes to have derived from genuine Dark Age traditions, characters, and events. For example, the round-table notion might have derived from the Celtic practice of chieftains and their leading warriors sitting in a circle so that feuding over precedence could be avoided; the Isle of Avalon and its nine guardian maidens seem to have arisen from the Celtic practice of sacred lake islands occupied by nine priestesses; and the casting of Excalibur to the Lady of the Lake probably originated with the custom of a votive offering to an ancient water deity. All these traditions existed around AD 500, so it is hardly surprising to find them interpolated into tales of a prominent British leader who lived at that time. The same applies to various characters in the Arthurian saga having Dark Age mythological counterparts: for example, Morgan le Fey and Mórrígan, Guinevere and Gwenhwyfar, and the Grail guardian Bron as the legendary hero Bran. They were all incorporated within mythology as it existed during the period Arthur is said to have lived. And we have also discovered that some of the key players in the saga, such as Merlin, Uther, and Vortigern, were almost certainly based on real people who lived in the right place and at the right time to have been associated with a genuine King Arthur’s life. Even the dragons can no longer be seen as a reason to dismiss Arthur as a historical figure.

The tale of the two dragons Merlin is said to have released from a cave under Vortigern’s fort at Dinas Emrys originated with a legend concerning Ambrosius that existed centuries before the medieval romances were composed. In fact, the legend related by Nennius might even have been based on an actual event, not involving real beasts, of course, or even drug-induced hallucinations, but on the discovery of a historical relic. In his narrative Nennius uses the terms dragons and serpents when referring to the creatures: “The two serpents are two dragons,” he says at the end of the anecdote. Today the word serpent generally means “snake,” but in Nennius’s time it also meant a mythical snakelike creature with legs and wings that breathed fire: in other words, a dragon. Dragons came into British mythology from the Romans, who took the concept from the Greeks. (The Greeks had adopted the idea from the Persians, via India, and originally China.) The confusion between the word for snake and dragon came about because the Greek word drákōn, from which the Latin and Brythonic words draconem and draig derived, meant both “dragon” and “snake.”1 The Dinas Emrys dragons, described this time as “serpents,” appear in an early Welsh tale called Lludd and Llefelys, preserved in The Red Book of Hergest.2 It actually explains how they came to be where they were: the two serpents, the tale relates, were originally hidden in the Dinas Emrys cave by one King Lludd, a legendary character who is said to have ruled Britain before the Romans came. Interestingly, these serpents were not huge fire-breathing dragons as we might imagine, but small enough to be placed in a cauldron, so presumable little more than a couple of feet long. They weren’t even living beasts, according to the Welsh triad, The Three Concealments.3 This poem specifically refers to the twin serpents as a sacred relic. The “concealments,” we are told, were the head of Bran, the bones of a saint, and “the dragons which Lludd son of Beli buried in Dinas Emrys.” All three were said to be talismans to ward off invasion. In other words, the two serpents were some kind of artifacts. They may even have been a single figurine of some kind, depicting intertwined serpents.

In Welsh legend Lludd was the last high king of Britain before the Romans invaded. It’s doubtful the Britons had such a supreme leader at the time—the Romans certainly don’t refer to one—but during the fifth century the tradition existed that Lludd had been a real king. Judging by Welsh literature, at the time Ambrosius lived this legendary king was considered to have long ago united the country. Presumably, therefore, the young Ambrosius, being the one to find Lludd’s twin serpents, implied that the boy was destined to reunite and lead the Britons in their struggle against foreign invasion. The double-serpent motif is found elsewhere in the Arthurian saga with regard to Arthur’s sword. Its earliest description is found in a Welsh tale preserved in The Red Book of Hergest, The Dream of Rhonabwy, which describes the sword as having “a design of two serpents on the golden hilt.”4 In the medieval romances, Excalibur was Arthur’s symbol of authority. Accordingly, something decorated with twin serpents is Arthur’s verification as king, just as the two dragons found by the young Ambrosius attest to his future leadership. This suggests that Lludd’s talismans may, like the sword, also have been a single item bearing similar ornamentation. But why this particular design? The answer seems to be that the twin-serpent motif had been the emblem of a chief god of the ancient Celts.

According to Julius Caesar in his Gallic War, the Celts “worship principally the god Mercury, having many images of him.”5 He goes on to say that the deity was believed to guide them in battle and grant them great influence and acquisitions. As we saw in chapter 5, the Romans usually equated foreign deities with their own, such as Minerva being the name they used for a British water goddess. As such, Caesar is using the god Mercury as the nearest equivalent in the Roman pantheon to this particular Celtic deity, although the Celts would have called him by another name that is now unknown. An apparent depiction of this god survives in the decoration on a silver cauldron found in a peat bog near Gundestrup, Denmark, in 1891. The so-called Gundestrup Cauldron is a bowl thought to have been used for ceremonial purposes. Dating to the first or second century BC, it was made by the Celtic people who migrated to Denmark from Gaul. A number of mythological images are depicted on the cauldron, but one panel appears to show the chief Celtic god. He is sitting in a kind of half-lotus position with his eyes closed as if meditating; on his head he wears an antler headdress, and in one hand he holds a huge serpent.6 This representation of the deity makes it clear why Caesar would have associated him with Mercury. In Roman art Mercury was depicted with a winged helmet, similar to the antler headdress of the Celtic god, and he held a serpent wand. Mercury’s wand was a short rod with two snakes entwined around it. Known as the caduceus, it symbolized, among other things, unity. The motif of two serpents said to have decorated Excalibur’s hilt probably had the same meaning as the dragons, or more likely a twin-serpent talisman, said to have been uncovered by Ambrosius. They symbolized British unity: their owner was the fated overlord of the Briton’s chieftains and kings.

As seen, the Arthurian legend seems to have had its roots in the area once encompassing Gwynedd and Powys, and there is persuasive, historical evidence that the first of these kingdoms already had the dual serpent as its tribal emblem well before the late fifth century. The Notitia Dignitatutm (Register of Dignitaries), a Roman document illustrated with military insignia compiled in the early 400s, includes a picture of a shield bearing the insignia of two crossed serpents.7 The accompanying text identifies it as the crest of a military “regiment” called the Segontienses Auxilium Palatinum or Segontium Imperial Support Unit in English. This unit, consisting of around a thousand men, was comprised of British soldiers enlisted to patrol the area that later became the kingdom of Gwynedd.8 (The city of Segontium, modern Caernarfon, was the regional capital.) Such auxiliary troops, being made up of local people, often adopted the region’s tribal emblem as their unit’s insignia. The dual serpent was therefore probably the emblem of the Deceangli tribe, native to northwest Wales. In conclusion, like many of the other Arthurian themes that at first appear purely imaginary concepts, the Dinas Emrys dragons have a firm, historical foundation in the post-Roman era.

Having examined the seemingly fanciful themes contained in the Arthurian saga, we can now appreciate that contrary to making a case for refuting Arthur as a historical figure, they actually help bolster it. They nearly all seem to have been based on genuine historical or mythological matters contemporary with the period Arthur is said to have lived. Rather than being medieval fables, they have authentic post-Roman counterparts that might easily have surrounded an important British leader who lived around AD 500.

One final issue regarding the case against Arthur as a historical figure concerns the anachronous setting for the events. The Arthurian romances, written between the mid-twelfth and mid-fifteenth centuries, depict Arthur as a medieval king: he fights with a lance and broadsword, is surrounded by knights in shining armor, and lives in a Gothic castle. However, if the action took place around AD 500, as these stories imply, then the entire scenario would have been very different. Arthur’s warriors would certainly not have been “knights,” as both the term and the institution of such honored fighting men did not exist much before 1100; neither would they have worn the kind of elaborate plate armor we normally associate with the Knights of the Round Table, as it wasn’t invented until the period during which these stories were composed. Weapons like the mace, the jousting lance, the longbow, and the broadsword, often seen in romantic Arthurian paintings, movies, and TV shows, weren’t developed until the later Middle Ages either. Soldiers of the early Dark Ages would have had late Roman-style clothing and armaments: lighter swords, short-range bows, slow-to-load crossbows, and chainmail and leather for protection—though unlike the earlier Roman army, helmets would have been a rarity, reserved for the elite. Even such reasonably equipped soldiers were few. As Britain was in a state of turmoil and Roman-type civilization had virtually collapsed, steel making and weapon manufacture had been reduced to little more than cottage industries, meaning that most native Britons went into battle with no protection at all, beyond a wooden shield, and armed with a simple spear or farm implements adapted for the purpose. The great castles with thick stone walls, battlements, turrets, moats, and drawbridges were also features of the later Middle Ages. Fortifications in post-Roman Britain would have been wooden stockades, built atop earthen ramparts, surrounded by ditches.9 Such glaring inaccuracies, skeptics argue, make the entire Arthurian story completely implausible. Not at all: medieval writers simply had limited knowledge of the early Dark Ages.

Although the medieval Arthurian romances were based on earlier Dark Age accounts and traditions, they were set against a background of life, morality, religion, social status, and warfare as it existed at the time of writing during the Middle Ages. Accordingly, warriors were knights, chieftains were kings, bards were wizards, forts were castles, and so forth. Medieval authors had no idea what ancient times were really like. All they had to go on were written and oral accounts concerning the purported actions of Arthur and his contemporaries, with no detail regarding their life and times. It was a good few centuries after the romances were composed before scholars learned what we now know about the Roman and post-Roman eras. Just take a look at any medieval painting of the Crucifixion, for example, and you will see the participants dressed in the clothing contemporary with the period of the artist. Even in the late 1500s, Shakespeare’s plays concerning the ancient world are filled with anachronisms: in Julius Caesar and Antony and Cleopatra, for instance, the stage sets depicted Gothic castles and Tudor mansions, while actors performed the part of Roman dignitaries in the costume of Elizabethan courtiers. Murals, mosaics, and sculptures did survive from the Roman era, but there were few to be found in Britain before the advent of archaeology in the nineteenth century. Even such works of art that survived in plain sight in mainland Europe could not be put into any kind of historical context until after the collapse of the Byzantine Empire in the mid-fifteenth century, when Roman historical records found their way into Western Europe (see chapter 7). And it was not until two centuries later that Western scholars finally began piecing ancient history together.

It was on such grounds that I had already addressed the case for disregarding King Arthur as a historical figure. What reason, however, had I to believe the legend was based on a real-life individual? To begin with, there was the historical context. Arthur is said to have been a powerful leader who united the Britons against the invading Anglo-Saxons in the late fifth or early sixth centuries. Even if there had never been a man named Arthur, someone who precisely played this role around the year AD 500 did certainly exist.

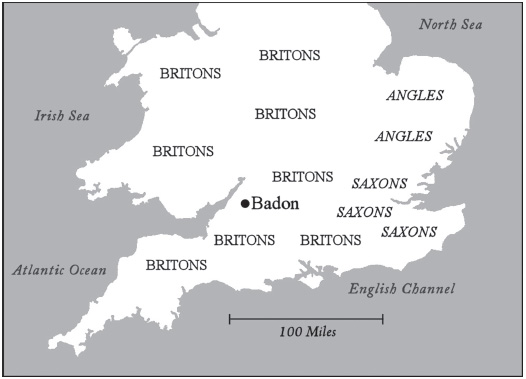

In chapter 8 we examined how, after the time Ambrosius led the Britons in the 470s, both the archaeological and historical evidence reveals that the Anglo-Saxons were on the offensive again in southern England. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records new Saxon invasions in the modern counties of West and East Sussex and in Hampshire.10 In alliance with the Saxons in the southeast—in today’s counties of Kent, Middlesex, and Essex—by the mid-490s they were advancing northwest toward the modern counties of Wiltshire and Somerset. Gildas and Bede give no specific information concerning this period, other than to say that there were successes and failures on both sides. But then everything changed. The Chronicle records no Saxon victories between 495 and 508, except for an isolated skirmish on the south coast in which a British noble was killed. As noted, this in no way means that nothing was going on. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle celebrated Anglo-Saxon victories and pretty much left out British accomplishments altogether. For example, it makes no mention of Ambrosius or his period of triumph over the invaders. In reality, it seems as though the Anglo-Saxons endured a crushing defeat at this very time. According to Gildas, who wrote within living memory of the events, the Britons achieved a crucial victory at a place called Badon Hill.11 Even Bede, an Anglo-Saxon, concurs with this.12 The very similar Baddon (pronounced “Bathon”) was the Brythonic name for the city of Bath, leading many historians to conclude that the battle took place somewhere in that area, probably at a fort on Little Solsbury Hill, just outside the town. If this is right, then the battle was of extreme strategic importance. Bath is close to the English west coast, meaning that had the Britons lost, the British forces in central England and Wales would have been completely separated from their compatriots in the south and southwest. Divide and conquer, as the saying goes.

A precise date for the Battle of Badon—as it is usually referred—is difficult to determine. Gildas is the only source for establishing when it occurred. However, when he refers to the event, Gildas’s Latin is somewhat confusing. His dating translates as: “And this happened, I know for certain, as the forty-fourth year, with one month now elapsed; it is also the year of my birth.”13 He tells us it occurred the year he was born, that much is clear, but the allusion to forty-four years is rather vague. Some historians consider it to mean that the battle took place forty-four years after the Anglo-Saxons were invited into Britain by Vortigern, something Gildas discusses earlier. Gildas gives no date for this particular event, but the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records it as 449, which would mean the Battle of Badon occurred in 493. Others, however, interpret Gildas to mean that the battle occurred forty-four years before the time he was writing, which, based on the contemporary events described in his work, was in the mid-540s, dating Badon to AD 500, give or take a year or so. One way or the other, the Battle of Badon had to have been fought somewhere between around 493 and 503. It was certainly a significant turning point in the struggle between the two sides, as both archaeology and the surviving historical sources evince that the Saxons withdrew to the southeast for well over half a century. For example, the kingdom of Sussex, which had initially been so militarily successful, appears to have been completely eradicated by the Britons, as the Chronicle makes no further reference to it or its kings until it was reestablished one and a half centuries later, while archaeology has discovered no evidence of Saxon burials outside the southeast for almost the entire sixth century.14

All this implies that sometime during the 490s the Britons had, as during the period of Ambrosius’s leadership in the 470s, again united behind a strong leader and successful military commander. The problem is that no inscription or contemporary source still survives to reveal who this was. Whoever this person may have been, he presumably led the Britons at the Battle of Badon, but frustratingly Gildas fails to name him; neither does Bede. So there is a gaping hole in our historical knowledge concerning the important period around AD 500. The Britons clearly had a powerful, unifying leader who dealt a crushing blow to the Anglo-Saxons at the very time Arthur is said to have been just such a figure. If a man called Arthur did not exist, then someone who did exactly what he is said to have done certainly did. Arthur, however, was the only name linked to this battle during the Dark Ages.

Fig. 9.1. Southern Britain before the Battle of Badon.

Other than in the works of Gildas and Bede, the oldest surviving reference to the Battle of Badon is found in Nennius’s Historia Brittonum, written around AD 830. The other two monks may not name the Briton’s leader at the battle, but Nennius does—he identifies him as Arthur.15 Actually, he lists twelve battles Arthur foughtagainst the Anglo-Saxons, Badon being the last. You might think the fact that one of the chief literary Dark Age sources names Arthur in association with the battle would be reason enough for scholars to accept that he was probably a historical figure. However, Nennius’s description of the battle, although brief, has been interpreted as legend rather than history. Nennius tells us: “The twelfth battle was on Mount Badon, in which nine hundred and sixty men fell in one day from one attack by Arthur, and no one overthrew them except himself alone.”16 Skeptics infer from this that Nennius was saying that only Arthur, and no other warrior, fought on the British side. In other words, he killed 960 Saxons all by himself. Conversely, the sentence can just as easily be interpreted to mean that Arthur was the only British leader involved in the fight: no other regional king or chieftain was involved, and it was Arthur’s personal army that beat the Saxons unaided by others. As conflicts are so often described throughout history, the victors’ leader is said to have prevailed: Julius Caesar conquered Gaul; George Washington defeated the British; Alexander the Great overthrew the mighty Persian Empire. It’s just a figure of speech. None of these people did it all alone; when we write about them today, we are not implying they did. It is simply easier to say “Julius Caesar conquered Gaul” than “Julius Caesar and the Roman legions under his command conquered Gaul.” Ancient historical commentators, no matter in what language they wrote, were no different from us. As far as I was concerned, the argument that Nennius’s reference to the Battle of Badon was farfetched just did not hold water.

Another Dark Age historical source also mentions the Battle of Badon, again associating it with Arthur. The Welsh Annals contains the entry: “The battle of Badon, in which Arthur carried the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ on his shoulders for three days and three nights, and the Britons were victorious.”17 Skeptics have two main objections to this as evidence for Arthur’s existence. First, it sounds ridiculous: a British general leading his troops while dragging around a huge wooden cross for three days. However, the phrase “carry the cross” meant, as it still does today, to keep the faith. The scribe was probably implying that it was Arthur’s faith in the Lord that allowed him to prevail. The skeptics’ argument got me thinking about a line from the nineteenth-century hymn “Keep Thou My Way.” The phrase “gladly the cross I’ll bear” has been creatively misheard as “gladly the cross-eyed bear.” I found myself calling such pedantic arguments “the gladly syndrome.” The gladly syndrome aside, the skeptics have another case for rejecting the Welsh Annals’ Badon reference that requires greater consideration. It lists the battle for the year 518, seemingly much too late to have been the period of the event described by Gildas.

In its surviving form, the Welsh Annals was compiled around 954. It does not actually use the AD system of dating, which did not come into standard usage until the later Middle Ages. Instead, it starts with the year Vortigern first invited in the Anglo-Saxon mercenaries, calling this “year 1.” It was a significant date, as it marked the so-called Saxon Advent, the beginning of much tribulation for the native Britons (see chapter 7). Bede, who did use the AD dating system, records the Saxon Advent as occurring in 447, so some historians infer this to be the Annals’ year 1. The Battle of Badon is inserted in what the Annals record as year 72, so if the year 1 is 447, the year 72 is 518. However, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle gives the year of the Saxon Advent as 449, which would mean that year 72 is 520, according to other historians. In fact, modern scholars have obtained additional dates for Vortigern’s invitation to the Anglo-Saxons, and so various translations of the Welsh Annals provide different dates for the battle, fluctuating by a decade or so either way. Nevertheless, we have seen that, from both the historical and archaeological perspective, the Saxon Advent seems to have occurred around 449, so the Annals’ year 72 does appear to be sometime in the late second or early third decade of the sixth century. In other words, the dating appears to be historically inaccurate. And if the dating is out by a couple of decades, the reference to the Battle of Badon is dubious, skeptics maintain. However, this does not necessarily follow. The evidently erroneous dating of the Battle of Badon in the Welsh Annals may well be due to the different chronology schemes employed during the Dark Ages. Some authors, like Bede, used the AD system, placing the year 1 at the birth of Christ, while others began year 1 at the Crucifixion. This actually resulted in more than just two dating systems, as scribes were uncertain as to when exactly Jesus was born or died. It was only later, after examination of second-century Roman texts, that a standard year for the Nativity was agreed.18 During the period the Welsh Annals was compiled, the texts transcribed to form the work would no doubt have varied wildly regarding specific dating. It is hardly surprising, then, that the surviving Annals exhibits confusion regarding some of its chronology. Consequently, the Welsh Annals placing Badon too late to fit into a historical context is no reason to dismiss the chronicler’s assertion that Arthur was the Briton’s leader at the battle.

So where does this leave us? As discussed in chapter 7, the key historical Dark Age sources covering Britain of the post-Roman period are limited to just five: Gildas, Bede, Nennius, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, and the Welsh Annals. As four of them reference the Battle of Badon, one of them written within living memory of the conflict, we can be fairly confident that it was a historical event. The only source that fails to mention it is the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which excludes almost entirely any success by the Britons. Of the four, two fail to say who led the Britons, while two say it was Arthur. As these historical sources associate no one other than Arthur with British leadership at the Battle of Badon, I decided that, on balance, it was a fair conclusion that he had been a historical figure. Indeed, closer examination of Nennius’s work further convinced me that there was a real King Arthur behind the legend.

Fig. 9.2. Southern Britain after the Battle of Badon.

Skeptics have argued that Nennius should not be trusted as a reliable historian because he includes many purely mythological accounts in his narrative, such as the Britons being descended from the legendary Brutus of Troy (see chapter 2). However, in his history of Britain, Nennius usually includes details that prove remarkably accurate when compared with contemporary Roman accounts; for example, Caesar’s attempted invasions of Britain in 55 and 54 BC. Nennius was simply transcribing earlier material he had at his disposal. He tells us this himself at the start of his narrative: “I have heaped together all that I found, from the annals of the Romans, the chronicles of the Holy Fathers . . . the writings of the Irish and the Saxons, and the traditions of our own wise men [the Britons].”19 He is well aware that some of this material may be unreliable and apologizes: “I ask everyone who reads this book to pardon me for daring to write . . . I yield to whoever may be better acquainted with this skill than I.”20 He admits to be no expert historian, but feels he must preserve what he has compiled before it is lost to future generations. He leaves it to us to decide what is accurate and what is not. Although we should treat Nennius’s work with caution, it includes much reliable history. Accordingly, certain of his accounts that cannot be collaborated, when unfettered by myth and elaboration, should not be dismissed out of hand—such as the account concerning Arthur. Nennius simply, almost matter-of-factly, refers to Arthur as a warrior who led the Britons to victory over the Anglo-Saxons. He records when he lived and lists his battles, and that’s it. There is no attempt to elucidate or make Arthur part of a larger or fanciful picture. On the contrary, he tells us frustratingly little: nothing concerning Arthur’s origins, the location of his seat of power, or how, where, and when he died. All we really know comes down to a couple of lines.

In that time the Saxons strengthened in multitude and grew in Britain. On the death of Hengist, Octha his son passed from the northern part of Britain to the kingdom of Kent and from him descend the kings of the Kent [he became Kent’s king]. Then Arthur fought against them in those days with the kings of the Britons, but he himself was leader of battles. 21

There is nothing fanciful about this passage. Quite the opposite: it fits perfectly into a historical context. We know that Hengist was a historical figure who enjoyed considerable success fighting the Britons in 473, just before Ambrosius went on the offensive (see chapter 7). We also know that Kent was a kingdom that remained firmly under Saxon control throughout the era. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle repeatedly records Hengist as a king of Kent, although the year of his death is unknown. Octha is not mentioned in the Chronicle, but he too appears to have historically existed. He is named in an Anglo-Saxon genealogy contained in a manuscript cataloged as Cotton MS Vespasian B vi in the British Library, dating from around AD 810. Here Octha is recorded as a king of Kent under the Old English Ocga Hengesting (Octha, son of Hengist). It seems he was indeed Hengist’s son as Nennius states. Nennius’s assertion that Arthur began his fight against the Saxons at the time Octha succeeded to the Kentish throne makes perfect sense. Going by the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and the genealogy in the Cotton Vespasian, this would have to have been in the late 400s, precisely the time Arthur is said to have come to power.

So there you have it. All this may not prove that Arthur historically existed, but it gave me, as I stated in chapter 1, good reason to regard him as an enigma worthy of further investigation. And that investigation had led me to the British kingdoms of Gwynedd and Powys.