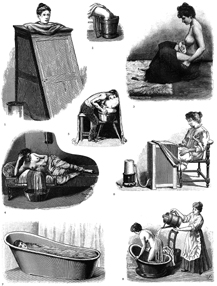

The water cure advised patients to take water in a variety of ways, from steam baths and full tubs to showers and foot and sitz baths. Each application served a specific purpose in the hydropathic regimen and was specially prescribed depending on the patient’s particular ailment and her ability to endure treatment. (Anatomical and Medical Illustrations, ed. Jim Harter, Dover Publications, 1991)

Announcing the November 1850 birth of his daughter in the pages of the Water-Cure Journal, Thomas Nichols declared that childbirth could be both easy and nearly pain free for women. His wasn’t the smug and unknowing opinion of a man standing idly by while his wife labored for hours in another room. His wife, in fact, fully agreed with him.

Mary Gove Nichols achieved her miraculous birth with a strict daily regimen. She avoided alcohol, caffeine, dirt, and all medicines. She exercised regularly, ate healthy foods, wore comfortable clothes, and took daily baths in cold water—and it hadn’t worked just for her. As a midwife to others, Mary described the pain experienced by women under her care as “slight” and not the “pangs worse than those of death” experienced by most women. Throughout her own pregnancy, Mary published reams of advice on how to achieve pain-free childbirth that were hardly a guarantee, much less a panacea, despite her devotion.

Mary’s secret was hydropathy, a system of healing that relied on the power of cold, pure water. Both husband and wife knew that water produced healthy pregnancies from Mary’s own experience. She’d suffered the agony of four successive stillbirths before submitting to its rigorous but healthful routine. The efficacy of the water cure for pregnancy and childbirth “comes so near the miraculous, that I hardly expect to be believed,” wrote Thomas.1 But believe people did, especially since the advice came from the Nicholses, who went on to become two of the most influential and authoritative advocates of hydropathy in the nation.

Today, when it seems that most Americans carry a water bottle to drink their eight daily glasses, the importance of water to health seems obvious. But for hydropaths, water was more than just a sugar-and calorie-free drink: it was a social good able to cure nearly every disease as well as the social and cultural ills that threatened the health and stability of society. Drinking was not the only way to enjoy water’s munificence, though; water was also to be experienced through elaborate rituals of bathing, showering, soaking, sweating, and wrapping. This diversity of baths, not to mention the idea of bathing itself, was highly unusual for most Americans. In 1835, a letter from a reader in the Boston Moral Reformer asked, “I have been in the habit during the past winter of taking a warm bath every three weeks. Is this too often to follow the year round?”2 Hydropathy was not a medical system in the traditional sense of a doctor administering treatment to a sick patient. Instead, it functioned more as a water-based lifestyle plan with a vision of radically transforming the world through personal health achieved through nature’s purest substance.

Hydropathy grew out of the observations and experiments of Vincent Priessnitz. A peasant born in 1799 on a farm in Silesian Austria, located in today’s Czech Republic, Priessnitz noticed as a child how cold-water compresses could ease the pain of sprains and bruises. Water’s potential as a cure-all revealed itself to him after an 1816 farm accident. One day while he was baling hay, a runaway horse and wagon trampled the teenaged Priessnitz, leaving him with several broken ribs and a bruised left arm. The doctor from a nearby town told him that the severity of his injuries made it unlikely he’d ever work again. Priessnitz, however, refused to accept this prognosis.3

Priessnitz began testing the power of water to ease what drugs and heroic therapies could not. He wrapped himself in wet cloths and ate very little while consuming large quantities of cold water. To reset his broken ribs, he pressed his abdomen against a chair and inhaled deeply, allowing the expansion of his chest to push his ribs back into place. Priessnitz eventually recovered from his injuries, and the success of his self-cure led him to broaden his investigation into the curing power of water. Similar to those of his irregular healing brethren, his story of discovery became an integral part of his developing system, a “personal revelation” about the failure of regular medicine and an awakening to the possibilities of a cold-water cure.4

As word of Priessnitz’s success spread throughout his village, others came seeking his council. Priessnitz treated people with water internally and externally. He soon gained a notable reputation for his achievements. To care for all who came to him for help, Priessnitz opened the Grafenberg Water Cure, sometimes referred to as “Water University,” in the mountains of Silesia in 1826. By 1829, he had perfected his method of water-based healing.5

Priessnitz treated patients with water in three ways: externally, by bath or shower; locally on certain parts of the body, through washing and soaking; and internally, through drinking or enemas. Nearly as important as the water, he stressed the importance of the doctor-patient relationship, and how clear communication and human touch contributed to wellness.

It’s not clear if Priessnitz actually understood how his system worked. He made hazy reference to cold water’s ability to relieve inflammation and to restore healthy fluids lost by disease. But mostly he fell back on perhaps the most intuitive and basic explanation for its efficacy based on his observations: water dissolved disease particles and carried them to the skin, where they could be washed away. Priessnitz believed that sickness resulted from some kind of contamination in the body that he called morbid matter, an idea common among both regular and irregular medical practitioners. Bleeding, vomiting, and drugging, the tools regular medicine used to eliminate disease, only weakened the body and ruined its natural systems, argued Priessnitz.6 The process of expelling disease in his system caused a “crisis” in the body that produced visible results such as boils, rashes, diarrhea, sores, and sweating. All were signs that the treatment was working. Priessnitz prescribed cold baths, cold showers, cold compresses, and wet bandaging or blanketing to cleanse and open the pores, aid circulation, and invigorate the skin as it drew putrid matter out of the body. As if that wasn’t enough water, he also ordered patients to drink a minimum of ten to twelve glasses of cold water per day. Taking Priessnitz perhaps a bit too literally, English doctor James Wilson claimed to have drunk thirty glasses of water before breakfast each day of the eight months he spent at Grafenberg.7 He also took nearly one thousand baths and spent 480 combined hours wrapped in wet sheets during his stay.8

The idea of therapeutic bathing wasn’t new. Humans have soaked in communal baths and natural mineral springs since antiquity. The ancient Romans, for instance, took bathing to elaborate heights, constructing ornate baths near mineral springs where the wealthy could “take the waters” while also indulging in other pleasures of the flesh. The Japanese have enjoyed hot springs known as onsen for at least a thousand years, and many European explorers noted the bathing rituals and sweat lodges used by some Native Americans in North America. Most of these early bathing practitioners did not attribute the health benefits to the water itself. Instead, the water was thought to have mystical qualities or to contain spirits released by the action of the water. Hydropaths, in contrast, viewed water as the cure in and of itself.9

Priessnitz’s method also differed from the spa therapy that had accompanied regular medicine in Europe for centuries. Most noticeably, the waters at Grafenberg had no particular chemical distinction, unlike the famous spas of Bath in England and Karlsbad in Germany, where patients soaked in warm springs and drank the mineral waters. At these spas, water was administered in only two forms—drinking or dipping—and it was always warm and never cold. Regular physicians recommended spa therapy for only a small number of conditions, including rheumatism, gout, and bladder stones. Even at its height in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, spa therapy comprised only a tiny fraction of a doctor’s regular practice, and water was never the sole therapeutic agent; water was simply one part of a treatment plan that usually involved the more common heroic therapies of bleeding and purging. Perhaps the biggest difference between spa therapy and hydropathy, though, was the atmosphere. Many people were drawn to the therapies at Bath Spa in England not for medical purposes but to enjoy the dancing, drinking, gambling, and seducing that occurred in and around these popular watering holes. Hydropathy, in contrast, focused almost exclusively on healthful activities, and its patients tended toward the earnest and somber. Merriment and debauchery would only distract them from their goal: the perfection of humanity through individual health.10

The medical benefits of cold water were not unknown to regular doctors. Despite the popularity of spas, many physicians criticized the value of warm mineral springs for fighting disease, not to mention the unhygienic conditions that existed inside many of the bathhouses. These critiques led to countless books on the curative powers of cold water in the eighteenth century with titles like Psychrolusia, or History of Cold-Bathing; The Curiosities of Cold Water; and An Essay on the External Use of Water.11 John Wesley’s popular eighteenth-century medical manual, Primitive Physick: Or, an Easy and Natural Method of Curing Most Diseases, asserted that cold water could cure nearly every disease if properly administered.12 These ideas were common in the United States, too. Benjamin Rush advocated the use of cold bathing to “wash off impurities from the skin.”13 Even with this attention to the medical benefits of water, cold water played only a small therapeutic role until Priessnitz popularized it as the one and only cure to all disease.

Washing disease away wasn’t Priessnitz’s only concern, however; he also sought to deny it entry into the body through a healthy lifestyle of diet and exercise. Hydropathy emphasized hygiene and healthy lifestyle choices far more than regular medicine and even more than other irregulars. Priessnitz argued that filth and poor diet gave disease easy access into the body. In The Hydropathic Encyclopedia, American hydropath Dr. Russell Trall explained that disease was “produced by bad air, improper light, impure food and drink, excessive or defective alimentation, indolence or over-exertion, [or] unregulated passion.” For Trall, it all boiled down to “unphysiological voluntary habits.”14 In other words, sickness resulted from laziness, a lack of exercise, and junk food, the familiar chords of obesity debates to this day.

Believing hot food, like hot water, dangerous, Priessnitz recommended cold foods at mealtimes and a diet free from stimulants such as alcohol, coffee, and tea. He also took the flavor out of most meals by outlawing mustard, pepper, and most spices. Hydropathic food tended toward the coarse and heavy for a sound and fibrous internal cleansing. Priessnitz explained that the way to strengthen a “weakened stomach is to avoid all the causes that have contributed towards destroying its tone.”15

Priessnitz also prescribed large amounts of exercise throughout the day. Working out, particularly after cold baths, helped to “stimulate the proper therapeutic reaction.”16 Walking outdoors became the most popular form of exercise, but in bad weather, patients could do gymnastics or even dance indoors. For some conditions, patients lifted weights or jumped rope. Others chopped wood. Women received the same prescriptions for physical activity as men; that women exercised and were highly encouraged to do so was very unusual at a time when frailty and fainting were prized feminine qualities.17

Priessnitz’s water cure in Grafenberg became renowned throughout the Western Hemisphere. Thousands came to take the cure, including many European princes and princesses, barons, and counts. Visitors marveled at Priessnitz’s ability to diagnose disease and devise a treatment plan simply by studying the quality and cast of a patient’s skin. He never checked the pulse, looked at the tongue, or asked patients about their complaints, the standard methods of disease detection. One patient who made the trip to see Priessnitz was Elizabeth Blackwell. Although not a fan of irregular medicine generally, she came in 1850 seeking relief for an inflamed eye. Diet and exercise strengthened Blackwell’s overall health, but her badly inflamed eye never cleared and eventually required removal. Even though his treatment failed Blackwell, Priessnitz’s therapy proved effective for most ailments, and by 1840, nearly seventeen hundred patients per year sought treatment at Grafenberg.18

Priessnitz’s success spurred countless imitators and admirers. Hydropathic institutes opened in England in the 1840s. Dr. James Wilson, of the thirty glasses of water before breakfast, opened his own water cure called Grafenberg House in Malvern, England, in 1842. Wilson gave each patient a Grafenberg flask so that they, too, could drink a few gallons of water before breakfast. Older health spas at Bath and Brighton refurbished and adopted Priessnitz’s now fashionable regimen. These English water cures attracted all kinds of people, including Scottish historian and writer Thomas Carlyle, author Charles Dickens, scientist Charles Darwin, and poet Alfred (Lord) Tennyson. Of these, Darwin was perhaps the most enamored of hydropathy. He returned home from Malvern and constructed an outdoor shower and bath in his garden that he used daily for five years under the ministrations of his butler. He also bought a horse for exercise and limited his work to two and a half hours daily, which he reported renewed his strength.19

Not everyone was so taken with Priessnitz’s successes, though. In the mid-1820s, physicians in the neighboring town of Friewaldau brought Priessnitz to court for practicing without a medical license. The court found Priessnitz not guilty, however. Because he used only water and no drugs of any kind, the judge determined that Priessnitz could not be said to be unlawfully practicing medicine. His acquittal won him and hydropathy even greater renown.20

Hydropaths trumpeted the ability of water to cure—or at the very least alleviate—all manner of acute and debilitating diseases that regular medicine had failed to treat. They emphasized water’s ability to cleanse, purify, soothe, cool, relax, renew, and wash away ills. Even with hydropathy’s sometimes hyperbolic praise of its power, water both gave and sustained life on earth, so critics struggled to deny its primacy and importance to health. Good health was natural, hydropaths argued, and it was the way God intended people to be. While hydropaths didn’t tend to claim spiritual awakening or communion for those who took the cure, they also didn’t deny these encounters if they happened to occur when someone was taking the waters.21

The first water cure in the United States opened its doors in 1843, followed by a second the next year. Both were in New York City and were operated by disillusioned regular doctors.22 Even before they opened, Americans had some familiarity with hydropathy. Newspapers and medical journals had carried stories and reports on hydropathy in Europe throughout the 1830s. Medical journals tended to be critical of the practice, pointing out the dangers and shortcomings of a single-remedy system just as they had done with Thomsonism. Some Americans had even visited water cures while traveling in Europe, bringing back firsthand accounts of their experiences. Americans had examples of water cures closer to home, too. Travelers had long raved about the healing merits of Saratoga Springs in New York, White Sulphur Springs in West Virginia, and Hot Springs in Virginia.23

Hydropathy spread quickly throughout the United States, largely due to the efforts of physicians Joel Shew and Russell Thacher Trall. In 1843 Shew abandoned his regular medical practice to open the nation’s first hydropathic institute. Tireless in his reform advocacy, Shew owned and operated several water cures over his life, partnered on others, and wrote books and articles extolling the power of water and the significance of the water cure to the history of medicine. Trall, another disaffected regular doctor, opened the country’s second water cure in 1844 and transformed hydropathy into an all-inclusive and very American healing philosophy that emphasized self-improvement and reform. Merging his interests in hygiene, food reform, phrenology, temperance, and vegetarianism, Trall crafted a system that left virtually no aspect of life unregulated, from work to sleep to meals and morals. For patients suffering from mental ailments, including “ungovernable passions” like anxiety, jealousy, and narcissism as well as other ailments like depression and sleepwalking, he recommended “mental medication” of “pleasant, cheerful, and sensible company, with a light and easy, yet regular and steady business occupation.” He suggested several options for sleep disturbances, including “Walking the room in a state of entire nudity,” which Trall declared produced “remarkably quiet and refreshing sleep” among some of his patients. Besides disease, he also counseled on the proper age of marriage, claiming that children born of young parents “are more animal and less moral and intellectual than those born nearer the middle period of the life of the parents.” He advised that the best marriages and the best children came from women aged twenty-two to twenty-five who married men between twenty-five and thirty years old.24 Not content to trust his patients to understand his dietary advice, Trall even published a hydropathic cookbook filled with bland, spice-free, mostly vegetarian recipes for whole-grain breads, gruels, and boiled vegetables.25 Trall based his theory on the laws of nature and made his hygienic system, with water as the central element, one that anyone could use, understand, and benefit from.26

Dissatisfied with the speculative nature of Priessnitz’s system, some American hydropaths did try to come up with their own theories for how hydropathy worked. Those that had converted to the field from regular medicine used their knowledge of disease and physiology to imagine how various impurities could invade the body. Germs were still decades away from discovery. These hydropaths proposed theories far more complex and sophisticated than those of the peasant Priessnitz to explain how cold water could heal everything: it dissolved morbid accumulations in the system and ejected them through the skin, lungs, bowels, and kidneys; it stimulated stronger action in the capillaries; it invigorated nerves; or maybe it drew blood from a place of excess to a deficient part.27

The water-cure movement spread through word of mouth and patient testimonials, a process fostered in large part by the Water-Cure Journal and the Herald of Reform and similar publications. These publications reported hydropathic innovations and dramatically highlighted amazing water-cure successes as well as the horrible failures of regular medicine. The Water-Cure Journal enjoyed remarkable success from its founding in 1845, acquiring more than fifty thousand subscribers by 1850, and surviving, under various names, until 1897.28 Some of that success may be attributable to phrenologists Orson and Lorenzo Fowler, who took over publication of the journal in 1848. Master salesmen but also true believers in both phrenology and hydropathy, the Fowlers occasionally touted the benefits of the water cure in the pages of their other popular periodical, the American Phrenological Journal.29 The mixing of these topics invited the criticism of the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal in 1846, for combining the “false schemes” of hydropathy with the “noble and lofty views which are the characteristics of Mr. Fowler’s [phrenological] philosophy.”30

Despite its generally low regard in many regular medical circles, hydropathy became incredibly popular among the American public. Hydropaths claimed their system aided rather than interfered with nature in its fight against disease, a popular position also claimed by Thomson and his botanics. Its natural curing agent and simple theory of disease offered a welcome and comprehensible alternative to the harsh drugs and the inaccessible language of regular medicine. Relying on the application and drinking of pure water rather than special mineral waters also allowed hydropathy to be easily adaptable to home use, which held particular appeal in a nation that expanded faster than it could produce trained doctors of any kind. Perhaps most appealing of all, though, was hydropathy’s new concept of healthful living: the promise of personal perfection through the adoption of the water cure. The system’s rules for eating, drinking, exercise, and sleeping provided a sense of meaning and order to followers while also giving them the autonomy to treat themselves: it was personal freedom within tightly controlled strictures. Many hydropaths set themselves up as lifestyle coaches, offering advice and answering questions on nearly every aspect of life. Hydropathy’s moral earnestness—many followers also advocated for temperance, vegetarianism, and even abolition—appealed strongly to lower- and middle-class Americans looking to improve their social and economic status.31

Hydropaths strongly believed, like many other kinds of nineteenth-century reformers, that improving the habits of the individual would uplift all of American culture if not the whole of humanity. They shared their generation’s boundless optimism in human potential and a romantic notion that Americans could achieve greatness through an act of individual will. Unlike other reformers, though, hydropaths avoided organized and formal political involvement. For the hydropaths, the clearest and best path to improvement lay in personal health. They painted a compelling vision of the good life and supplied the entire system by which they believed it could be achieved. “We labor for the Physical Regeneration of the Race, well knowing that only through this can we successfully promote the Intellectual and Moral Elevation of our fellow-men,” proclaimed the Water-Cure Journal. “We ask all who have brothers and sisters of the Human Family, to aid in this work, by becoming Co-Workers with us in the great cause of HUMAN HEALTH.”32 Hydropathy seemed to promise that if every person followed its method, humans could eliminate not only disease but all human suffering. The harmonious and moral society that would result would allow everyone to create and control his or her own future. Hydropaths were realistic, though. They realized that not every person would achieve their vision of perfection, but they applauded those who strove to reach it anyway.33

Mary Gove Nichols was a prolific writer and vocal advocate for the benefits of the water cure and of women understanding the workings of their own bodies. (Sarah J. Hale, ed., Woman’s Record [1853])

At the same time that Shew and Trall expanded hydropathy’s reach and theoretical underpinnings, it was Mary Gove Nichols and her husband, Thomas, who made hydropathy famous, even before they began flaunting the pain-free birth of their daughter. Born in Goffstown, New Hampshire, in 1810, Mary Sargeant Neal was the precocious daughter of a freethinking father who encouraged her active and curious mind. She started school at age two, and by age six, she had read all of Plutarch. After her family moved to Vermont, her formal schooling became more sporadic, but she continued her self-education by reading everything she could get her hands on. As a teenager, she pored over the pages of the books her medical student brother brought home, fascinated by the workings of the human body but perhaps also wondering why she could find so little information on the health of women like herself.

An unhappy marriage in 1831 to Hiram Gove, who disdained her reading and creative writing, helped turn Mary into a champion of women’s rights and a prominent health reformer. Trained as a hatter, Hiram lacked the skills to support his family, so Mary taught, sewed, and published stories and poems to sustain them, all the while enduring his contempt of her writing and personal correspondence. Marriage without love made each hour “an eternity of misery,” she wrote. Despite her unhappiness, Hiram refused her a divorce. To ease her mental and physical suffering, Mary defied her husband and turned back to the medical books that had so enthralled her as a child. She discovered Sylvester Graham, an early advocate of dietary reform, vegetarianism, and hygienic reform and determined that women’s well-being and happiness depended on the freedom achieved through personal health.34 Excited by her newfound knowledge, Mary wanted to share her message with others. She particularly wanted to tell other women of the salvation that could be found in knowing about and taking charge of their own bodies. Her husband’s disapproval of her activities, even as he benefited from the money she earned from her advocacy, only fueled her “burning zeal to save women from the miseries she saw, and from some that she endured.”35

In 1838, Mary Gove made a name for herself lecturing (a scandal in and of itself for a woman) on the shocking topics of women’s health, anatomy, and physiology. Women’s health was a topic rarely, if ever, discussed at the time, much less in public. With no women regular doctors, many women ignored their own health problems and endured in silence to avoid being seen by male doctors, which many deemed improper. An often sickly woman herself, much of it brought on by the stress of her terrible marriage, Mary made it her mission to relieve other women of the crushing burden of physical and mental suffering. Hundreds packed lecture halls to see the thin, dark-haired woman with an open and intelligent face and exuberant brown eyes discuss the healthy female body.36

In the summer of 1845, finally free of her husband after leaving him and returning to her parents’ home in 1841, Mary traveled to Brattleboro, Vermont, to investigate the water cure recently opened there by Priessnitz disciple Dr. Robert Wesselhoeft. Hydropathy wasn’t new to her; she’d been reading about it and advocating many of its principles in her lectures and writing for several years, but she lacked formal training in its tenets and use. Impressed by what she saw, she began training as a water-cure physician, offering physiology lessons to patients in exchange for her education.

The town of Brattleboro sat on the Connecticut River where it met Whetstone Brook and the West River in southeastern Vermont. Surrounded by mountains, forests, meadows, gorges, and waterfalls, the area offered plenty of outdoor recreational opportunities for patients taking the cure. “A more suitable spot for such an undertaking could not well have been chosen,” proclaimed one patient.37 Although Shew and Trall had opened urban water cures, most institutions operated in rural areas along rivers, streams, and lakes. Hundreds opened around the country in the 1840s and 1850s, some operating only a few months while others lasted more than a century. Most people who went to a water cure suffered from chronic diseases like asthma, dyspepsia, or gout. Visits tended to last one to three months. Nestled in bucolic settings, these facilities sold hydropathy but also the beauty and tranquility of the surroundings as a respite from the ills of a hectic urban life. The Elmira Water Cure in New York boasted of its sweeping hills and woods, “overlooking the entire city, the river and valley of the Chemung, and the hills around, giving miles of the most varied and beautiful scenery. Our elevation gives us dry and bracing air, so necessary in the cure of Catarrah, Throat and Lung diseases, Rheumatism, Neuralgia, and Scrofula.”38 Many of the larger water cures had sleeping quarters, a dining hall, a bathing area, and an exercise hall. To protect women’s modesty, most cures had separate bathing facilities for men and women as well as female bath attendants, nurses, and even doctors.39

Water cures often aimed their services at a particular clientele—women, teachers, weary ministers, or people suffering from certain illnesses—but they also serviced a variety of patients who made their choice based on the scenery or attractions offered rather than on medical specifics. Round Hill House in Massachusetts recruited healthy people to come “for a season of recreation from the cares of business, where pure air, pure water, lovely walks and rides, and captivating scenery, may be enjoyed, without ‘stint or measure.’”40 Round Hill was one of any number of water cures attempting to attract those less interested in medical care than in recreation and social opportunities. Mark Twain found his visit to a European cure so pleasant he quipped, “If I hadn’t had a disease I would have borrowed one just to have a pretext for going on.”41

Wesselhoeft’s Brattleboro Hydropathic Institution was one of the most exclusive and expensive water cures in the United States. Initially welcoming eighteen patients, it eventually grew to accommodate two hundred at a time, among them some of the nation’s leading politicians, social reformers, and writers, including President Martin Van Buren and writer Harriet Beecher Stowe. Wesselhoeft had carefully examined several other springs before determining Brattleboro’s to be of superior quality and purity for the institution he planned. It also helped that the town was only a one day’s journey by train from Boston, New York, and Albany, major population centers that would provide clients to his fledgling business. Located on a quiet street away from Brattleboro’s main business district, the institute’s main buildings formed a square enclosing a courtyard with an elaborate fountain. Covered verandas offered areas for exercise in bad weather and cool breezes in the summer. Cold running water pumped into the separate buildings for men and women, each equipped with a variety of baths, as well as single and double rooms for sleeping. A “dancing saloon and parlor” connected the men’s and women’s buildings. Fresh water from springs located in the hills surrounding the town flowed continually into the plunge baths, twenty-five feet long and fifteen feet wide. In the nearby woods, patients found showers, twelve sitz baths (a waist-high bath used to treat lower-body ailments), an eye bath, an ear bath, and a river shower. Further on, a wave bath fed by the flume of a small millpond was located on the high bank of the Whetstone Brook.

Coaches met patients at the Brattleboro train station and brought them directly to the institute. One week’s stay cost eleven dollars in the winter and ten in the summer. The difference in price reflected the hydropathic insistence that cooler temperatures, like cooler water, made for more effective and comfortable cures; “even the severe cold of winter is no real obstacle to [the cure’s] continuance.”42 The price didn’t include the hefty supply of sheets and other equipment patients were expected to bring. Each patient was instructed to supply at least two large woolen blankets, a feather bed or three comforters, a course linen sheet for cutting into bandages, two course cotton sheets, six towels, and one injection instrument for enemas. Supplies could also be purchased on site. To save money, patients could also stay at a boardinghouse in Brattleboro and use the outdoor baths for the discounted rate of five dollars per week.43 Nonetheless, few Americans could afford the indulgence of a trip to Brattleboro at a time when the average wage of a male factory worker in the 1850s hovered around one dollar daily.44

Water treatment protocols differed from practitioner to practitioner and from patient to patient, but most hydropaths followed the pattern set by Shew’s first New York City cure. The wet sheet became the usual and most popular mode of application because it “cools febrile action, excites the action of the skin, equalizes the circulation, removes obstructions, brings out eruptive diseases, controls spasms, and relieves pain like a charm.” While the icy coldness of the fabric could be shocking at first, Thomas Low Nichols described a near immediate “pleasant glow, a calm, and usually a profound sleep” that quickly followed.45 While Priessnitz’s original system called for water to be used both internally and externally, most American hydropaths believed that water worked best when applied gradually through the skin. The wet sheet became the standard method of application. First, the attendant would dip a sheet of cotton or linen in cold water and spread it on several thick wool blankets. The patient would then be wound up in the sheet and blankets by the attendant and secured with pins or tape. Once wrapped, patients would shiver and then lie sweating on feather beds for anywhere from twenty-five minutes to several hours depending on the seriousness of the illness. After they worked up a good sweat, the attendant unwrapped them and plunged them in a cold bath followed by a brisk drying. For severely debilitated patients, the wet-sheet treatment could be too much, so an alternative known as the wet dress was used instead. A loose-fitting, nightgown-like garment, the wet dress allowed patients to dispense with the services of an attendant and to walk comfortably while also soaking up water. Most wet-dress patients also went to bed in the outfit, a damp and presumably clammy night of sleep.46

The wet dress soon found a following outside the water cure as well, influencing the mid-nineteenth-century Bloomer costume for women, the semiofficial dress of women’s liberation. The loose gown with wide sleeves and a skirt falling over baggy trousers seemed the perfect outfit for healthy women who sought comfort and freedom from the strictures of standard women’s wear. Popular fashion of the time called for tightly laced corsets, layers of petticoats, and floor-length dresses. Some women dragged fifty pounds of clothing around with them, making walking, not to mention breathing, challenging. Female water-cure patients reveled in the freedom of the wet dress, and they often took that freedom one step further and cut their long hair short for easy drying.47

Fed up with their restrictive clothing, many women—along with many progressive men—began advocating for dress reform as one part of a whole package of rights and freedoms for women. Elizabeth Smith introduced her modified-for-street-wear wet dress to the fashion world in 1851 after sharing her new style with her cousin and women’s rights leader, Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Journalist Amelia Bloomer discovered it when Stanton came for a visit and showed off the new style. Bloomer soon began writing enthusiastically about it in the Lily, the nation’s first reform newspaper for women. So great was Bloomer’s fervor that her name became indelibly linked with the style, though Bloomer and her fellow wearers suffered merciless ridicule for their fashion choice. Bloomer abandoned the style in 1859 but not her desire for more reasonable clothes as she continued to advocate for sensible women’s clothing throughout her life.48

The wet sheet and dress were but one tool in an intense regimen of bathing, soaking, walking, and showering. Educator Catharine Beecher was an early and active promoter of hydropathy, and she came to Brattleboro in the summer of 1846 seeking ways to improve her health. Rarely sick as a child, Beecher claimed that it was only once she had to earn a living as a teacher, confined indoors all day, that she suffered her first nervous breakdown.49 Packed into a wet sheet at 4 a.m., Beecher remained wrapped like a waterlogged mummy for hours. As her body heat warmed the sheet, she began to sweat profusely beneath her tight wrappings. Beecher was then unwrapped and immersed in a cold plunge bath. This morning soak was only the beginning of her day. She was then sent outdoors to walk as far as she could, drinking five or six tumblers of cold water to stay hydrated before and after her exercise. Many patients walked to Cold Spring, a beautiful pure water stream running down from the mountains. Another path meandered from Elliot Street, where the institute was located, past a woolen mill, along shaded roads and trout streams, to Centerville and back. Returning from her walk, Beecher stood under an eighteen-foot-tall cold-water shower for ten minutes. After this she walked and drank some more. At 3 p.m., Beecher sat in a sitz bath filled with cold water for thirty minutes. She then walked and drank again. At 9 p.m., she sat for thirty minutes with her feet resting in a bucket of cold water. Beecher ended her day as it began nearly seventeen hours earlier, wrapped in wet bandages. She repeated this experience every day of her three-month stay. Her experience and those of others she’d observed convinced her that water cures should be “multiplied all over the land, as the safest and surest methods of relieving debilitated constitutions and curing chronic ailments.” “Without exception,” declared Beecher, “all are improved in general health, [and] . . . none are injured.”50

Methods varied depending on the nature of the complaint. In 1849, a thirty-two-year-old woman with dark hair, gray eyes, and a ruddy complexion came to Dr. Wesselhoeft seeking relief for dyspepsia (indigestion), back pain, and fatigue. She’d tried everything, from pills, powders, herbs, and teas to Thomsonism with no relief. She estimated she’d been bled at least twenty times. Wesselhoeft examined her and determined that her dyspepsia was long gone, replaced by sickness generated from all of the medicines and treatments she’d tried. He first had her bathe before he wrapped wet bandages around her stomach and abdomen. She drank water and received several enemas. He then wrapped her in a wet sheet until boils appeared, “sure that all would go on well.” The boils healed but the patient only felt worse. The next day, she began to “vomit large quantities of bile and—worms! Yes! This was her disease!” Wesselhoeft instructed her to drink sixteen tumblers of water and an attendant gave her four water enemas daily. She was told to eat nothing but peas, beans, and coarse bread, fiber to help the worms pass through her system. Finally, she endured three days of diarrhea, evacuating most of the worms and much of her strength in the process. Exhausted and weak from her ordeal, the woman then underwent a rehabilitation process that Wesselhoeft began to “return her to health.” He kept her wrapped in wet bandages, removing them each day as they grew brown and crusty as the disease left her body. More than a month later, the woman claimed her health at long last restored.51 Intestinal worms can cause vomiting and diarrhea, though it’s unlikely that this woman actually vomited worms. Most intestinal parasites come from contaminated food or water or from contact with larva-infested soil. Fibrous foods can help them pass out of the body through the bowels, so Wesselhoeft’s treatment may have aided this patient’s natural body process of eliminating the worms. Hydropathy’s hygiene regimen perhaps helped to prevent reinfection and rehabilitated her with whole foods and water.

Wesselhoeft taught his students, Mary Gove among them, the art of individual prescription, adapting cures to each patient’s symptoms, stamina, and age. “The same treatment that would cure one might fail entirely with another,” she later noted.52 Hydropathy was very physical work for the physicians and attendants, too, requiring great strength to rub patients, lift blankets drenched with water, and to assist people in getting in and out of their beds, baths, and wraps. Mary left Brattleboro with a profound respect for the healing power of pure, cold water to cure nearly all disease given the appropriate skill, time, and dedication.53

After three months in Brattleboro, Mary became the resident physician at the New Lebanon Springs Water Cure in New York. But the rigorous physical demands of the work proved too much for her. She moved to New York City in 1846 and began giving lectures and writing articles and books on health and hydropathy. Twenty women signed up for her first series of twenty two-hour lectures on the structure and function of the body. That same year, 1846, her Lectures to Ladies on Anatomy and Physiology, first published in 1842, earned a second and much wider printing, as well as a positive review from the poet Walt Whitman and even the regular medicine periodical the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal. Edgar Allan Poe, writing in Godey’s Lady’s Book, praised her enthusiasm and speaking skills, proclaiming her “in many respects a very interesting woman.” Mary’s evident charms and reformist impulses attracted a variety of writers, philosophers, musicians, and artists to her home, including Poe, who recited “The Raven” in her living room, but also social reformer Albert Brisbane. Mary Gove’s clear and rational writing greatly enhanced the popularity of the water cure, and her references to the medical works of Hippocrates, Galen, and French physiologist Francois Magendie inspired reader confidence in her breadth of medical knowledge. Rather than adopting inaccessible medical jargon, she followed in the path of her fellow hydropaths and medical irregulars like Thomson. She appealed to the intelligence of her readers and spoke plainly to educate patients and practitioners. Mary continued to treat patients, many of whom traveled across the country seeking her services and advice. Though she’d never attended medical school, by the late 1840s, she led a doctor’s life and had earned a reputation as a trustworthy medical expert.54

Things were looking up in her personal life, too. Mary’s husband, Hiram Gove, finally consented to a divorce in 1847. That same year on Christmas Eve, she met a young writer named Thomas Low Nichols, whose writing and progressive views on women she admired. The two married the following July. Inspired by his new wife’s work in hydropathy, Thomas enrolled in medical school to study “the very errors and absurdities” of regular medicine, graduating from New York University with a medical degree in 1850.55

While residential water cures and the personalized services of practicing hydropaths like Nichols did attract the wealthy and famous like Mark Twain, Brigham Young, Susan B. Anthony, and Catharine Beecher, hydropaths consistently emphasized the importance of keeping their cures affordable. Yet, in the mid-nineteenth century, the average cost of a visit to a water cure ranged from five to fifteen dollars a week with additional charges for other services. Some institutions offered discounted rates to those patients who brought their own food and washed their own clothes. Even so, a visit to a water cure remained out of reach for many Americans, who could ill afford to miss work and spend half a month’s wages on a week’s worth of care. Most of those who could afford to visit a cure could also afford other kinds of health care, including regular medicine, so both regulars and hydropaths competed, at some level, for patients of a similar socioeconomic class.56

But, unlike regulars, hydropaths also made a philosophical commitment to accessibility and stressed the value of home care. Like the Thomsonians, hydropaths strongly believed that everyone should have access to health care and medical knowledge. They also recognized the pragmatic benefits of domestic hydropathy in spreading the water cure as widely as possible. Many hydropaths published home medical manuals and guides for self-doctoring that detailed the kinds, timing, frequency, and duration of baths required for particular illnesses, as well as information on exercise and diet.57

Hydropathy translated well to home use because of the responsibility it placed on patients for affecting their own cure. Passivity had no place in hydropathy. Patient cooperation and dedication to the process was essential, no matter where treatment occurred. Unlike regular medicine, hydropaths deemphasized the authority of the physician in favor of creating independent patients able to diagnose and care for themselves. Patients thus had a substantial responsibility for their own outcomes. “If a patient thoroughly understands his or her disease, and has the requisite energy to accomplish a cure,” wrote Mary Gove Nichols, “it may be done almost anywhere, and with very meager advantages.” She recounted stories of female patients who managed to heal themselves even while weak with disease through their own “indomitable energy.”58 Hydropaths believed that hygienic habits were best mastered through willpower and self-control, an ideology that mirrored wider societal beliefs about personal responsibility and social improvement. While this had the potential to render ill health a personal and moral failing, adherence to a system placed some but not all responsibility for healing on the efficacy of the system itself. Self-care allowed everyone to participate in hydropathy, and the success of the treatments, whether achieved at home or at a water cure, were widely publicized and given equal treatment in hydropathic journals.59

Empowering people to care for themselves went hand in hand with hydropathy’s rejection of university training as a prerequisite for practicing. Hydropathy was far less hierarchical than regular medicine and even other nineteenth-century irregular systems like homeopathy, in part because hydropaths never sought professional medical status. Anyone could practice hydropathy and find success, including the self-taught. While some debate arose in the 1850s over whether to establish uniform credentials and standards, proponents arguing that it would improve care and patient outcomes, hydropaths never seriously acted on the issue and it did not come up again in an organized fashion. Most hydropaths believed that the only qualifications necessary should be a personal commitment to the principles of hydropathy and a willingness and ability to practice them responsibly.60 Clearly, these principles and hygienic living were intended to eliminate the need for drugs and heroic therapies, and many hydropaths did insist that water cure and regular medicine shared no common ground or interests. But rather than compete directly with regular medicine, hydropaths instead believed that regular medicine would naturally fade away as it became increasingly irrelevant in the face of rising universal health and social harmony.61

Despite the egalitarian views of many hydropathic practitioners, in 1851, Mary Gove Nichols and her new husband, Thomas Nichols, opened the nation’s first hydropathic medical school, the American Hydropathic Institute, in New York City. Concerned about the dangers of the misapplication of cold water, not to mention charlatans masquerading as hydropaths for profit, the Nicholses believed that the potency of water required expert guidance. They hoped their school would make water-cure training more formal and respectable—a more professional alternative to regular medicine. Similar efforts continued among some hydropaths until well after the Civil War, most notably in New York City, where Russell Trall opened his New York Hydropathic School, later the Hygeio-Therapeutic College, in 1853. The Nicholses’ school offered a full medical course in anatomy, physiology, chemistry, surgery, and obstetrics and had all the necessary plumbing for a complete hydropathic education. Students could also visit hospitals, clinics, anatomical museums, and medical libraries in the city for additional learning opportunities. More than teaching about water, though, Nichols wanted to provide a medical education for women to meet the national demand for female doctors.62

With few exceptions, most of the nation’s medical schools refused to admit women. Elizabeth Blackwell had only been admitted to New York’s Geneva Medical College on a technicality after faculty passed the decision of whether to allow her admission on to the all-male student body. As a joke, they voted yes, and Blackwell matriculated despite the opposition of most of the students and faculty to her presence.63 At the American Hydropathic Institute’s inaugural ceremonies, Mary Nichols delivered an address entitled “Woman the Physician” that argued for the importance of female doctors. Rather than reject cultural assumptions about women’s caring nature, she claimed women’s innate talents uniquely qualified them for the profession. “Women are peculiarly fitted to practice the art of healing . . . [because of the] tenderer love, the sublimer devotion, the never to be wearied patience and kindness of woman,” she proclaimed.64 Thomas echoed his wife’s sentiments, writing in the Water-Cure Journal that women’s “diseases have been the subject of mercenary speculations, of mischievous medications, of torturing mechanical inventions, of nameless brutalities, and detestable charlatanism” with “little or no relief.”65 Enrollees in the American Hydropathic Institute understood from the start the reformist goals of its founders, and the Institute’s first graduating class included nine women and eleven men.66

The Nicholses’ progressive views of women aligned perfectly with hydropathy’s expansive view of women and women’s health. Hydropaths shared their era’s belief in women’s softer, more caring nature: they just did not see this as a justification for keeping women out of the medical profession. At the time, regular medicine tended to regard being female as a disease in and of itself. Ruled by reproduction, women were deemed irrational, intellectually inferior, and emotional, and their biological processes treated as illnesses in need of containment. Physician Edward Johnson, who used hydropathy alongside heroic therapies, fumed that regular approaches to childbirth were “irrational, indefensible and most preposterously foolish” in treating birth as though “it were some formidable and dangerous malady.”67 Hydropathy took the radical step of naturalizing women’s life stages. For hydropaths, puberty, menstruation, childbearing, and menopause were not dread diseases needing intervention but natural processes in a woman’s life. Women did not become weak and ill because of their gender but because of some outside cause, just like men. Hydropaths celebrated women’s nature and exalted rather than denied their historic role as family and community caretakers. They urged women to take an active role in their own health, and to maximize their health and happiness through diet, exercise, and other hygienic practices, all of which dramatically expanded women’s power to determine and control their own lives within the hydropathic worldview.68 As a result, hydropathy provided a refuge for progressive women, and many of America’s first generation of women doctors came out of hydropathy.

Encouraging women to get involved in hydropathy contributed to the financial health of the nation’s water cures as well. To attract women and their money, hydropaths needed female attendants and practitioners to serve them. Modesty and the intimate nature of the treatment demanded that women be treated and served only by other women. The large cures had at least one woman physician on staff, and most cures boasted of their male- and female-only bathing facilities in advertisements. A few cures had exclusively female staff and clients. It seemed to work. Women consistently outnumbered men in attendance at hydropathic institutes. It’s not hard to imagine why.69

For many women, visiting a water cure was the first, and perhaps only, time their needs were put above those of their husbands and children. As Dr. Silas O. Gleason of the Elmira Water Cure explained, “[T]here was a large class of patients for whom physicians could do little in their home environment. They needed a change of scene, systematic and constant oversight and the most healthful of mental, moral and physical aid, free from the cares and despondency that came of a routine that had grown depressing.”70 Gleason operated his cure with his wife, Rachel Brooks Gleason, a respected doctor in her own right, who counted Mark Twain’s wife, Olivia Langdon Clemens, among her patients.71 Writer Harriet Beecher Stowe was among the women who relished the break from her husband, children, and housework when she took the cure at Brattleboro. “Not for years, have I enjoyed life as I have here,” she admitted, “real keen enjoyment—everything agrees with me.” She loved the daily exercise—a real change from simply running after her children—and the companionship of the other women at the cure, which included, for a time, her sister Catharine Beecher. Stowe’s husband, Calvin, on the other hand, couldn’t wait for her return, reminding her that it had been “almost 18 months since I have had a wife to sleep with me. It is enough to kill any man.”72

Hydropathy’s popularity and the glowing testimonials to its curative powers did not mean that taking the cure was always pleasant. Some treatments, especially cold-water enemas, were common practices that few hydropaths discussed openly. That’s probably for good reason. For constipation or diarrhea, patients quickly drank at least two pints of water, enough to produce distension of the colon in some people. Sufferers of chronic or acute mucous discharges and other genital conditions received cold injections via a zinc wire straight into the vagina or urethra.73 The wet sheet wasn’t always a treat either. One Boston man reported that his sheet froze stiff in less than three minutes during a visit to a cure one winter. Even so, he still reported that it had done him good.74

Worse than the wet sheet was the shower for many patients. At a time when few people bathed regularly, let alone had ever experienced a shower, a cold hydropathic stream falling from a height of at least ten feet offered a rude introduction. Some patients shouted, struggled, and attempted to run away when the spray hit them. First-timers could be pounded flat by the force of the stream. One English patient recalled being knocked over “like a ninepin.” Another woman tried to lessen the force of the water by standing on a chair to decrease the distance between her head and that of the shower, but the water felled them both. The shower became even more perilous in winter when icicles could form and fall like daggers on the patient below.75

Drinking too much water could be deadly, too. Ingesting more water than the kidneys can properly handle can dilute the concentration of salt in the blood necessary for proper functioning of the body, a condition known as hyponatremia. Left untreated, a patient may lapse into a coma that can lead to death. It takes a lot of water to cause hyponatremia, but James Wilson perhaps flirted with danger, though unknown at the time, by drinking so many glasses of water before breakfast.76

Hydropathy’s critics delighted in recounting patients’ tales of peril from the nation’s water cures and heaped abuse on hydropaths. American medical journals did their best to discredit hydropathy by making frequent references to Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s harrowing 1736 experience at a water cure, where, Rousseau claimed, the waters had “nearly relieved me, not only of my ills, but of my life.” Few seemed to care that Rousseau’s visit occurred a century before Priessnitz had developed his system. Cartoonists loved to depict water-cure patients so swollen with water that they exploded or, alternatively, patients so saturated that they needed wringing out.77 After Catharine Beecher’s ringing endorsement of hydropathy and her experiences at Brattleboro appeared in the pages of the New York Observer, the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal sarcastically rejoined, “Ah! Blessed era for the washerwomen! How should the hotel chamber-maids rejoice? There is no longer need of airing or drying sheets . . . the miserable wretches who have gone out of the world with pleurisy and rheumatism, from sleeping in these damp envelopes, were entirely mistaken; they were actually better for it, or would have been had they not stopped too soon.”78

Not many irregular medical systems escaped the harsh gaze and withering critiques of Oliver Wendell Holmes, who traced the evolution of the water cure while critiquing another of his favorite targets, homeopathy, as yet another ridiculous and illogical system. Holmes characterized Dr. Wesselhoeft as one of many “empirics, ignorant barbers, and men of that sort . . . who announce themselves ready to relinquish all the accumulated treasure of our art, to trifle with life upon the strength of these fantastic theories.79 Many other people, including some outside medicine, agreed with him. On a trip to Europe, American writer John W. DeForest visited Priessnitz’s cure at Grafenberg. He complained not only of the treatment he received but also of the climate, the water regimen itself, and the food, which he called “an insult to the palate and an injury to the stomach.”80 Poet and writer John Townsend Trowbridge was more generous than Holmes and DeForest, praising the restful conditions he experienced while visiting a water cure even though the treatments provided him little relief from his so-called “nervous debility” that kept his mind constantly whirring and disrupted his sleep. He was less impressed with his fellow patients, however, whom he accused of being self-absorbed, concerned only with their invalidism, a topic of conversation he found “not cheeringly tonic.”81

Although hydropathy continued to be widely popular, pessimistic reports on the validity of a single-cure system continued to appear through the mid-nineteenth century. The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal reported that water had proved unsuccessful at treating most illnesses. Many regular doctors were convinced that hydropathic patients got better not because of the treatment but because its very mildness let nature do its job.82 And it was true that most patients who visited water cures got better. In part, it was because most patients had to travel to a water cure, which virtually excluded those with serious acute or critical conditions from the start. Even those who practiced at home had to have the strength and stamina to follow the routine. Most patients suffered mild or chronic complaints often brought on or aggravated by the stresses of modern urban living. To feel better, they needed only some rest and relaxation, which hydropathy usually provided. Some critics also pointed out that despite hydropaths’ claims to the contrary, the water-cure regimen was just as rigorous and invasive as heroic medicine with its weeks of wraps, long walks, showers, enemas, injections, and demands to drink more than ten glasses of water a day. Maybe it was better to be bled once than to endure more than fifteen hours a day in treatment, even if it was only water.83

Hydropaths themselves struggled to stay loyal to water as a cure-all. Practitioners came to hydropathy with varying levels of qualifications, experience, and motivations for practicing. From the very beginning, some followers combined water cure with homeopathy, vegetarianism, medical gymnastics, and vapor baths. Sylvester Graham’s hygiene program, especially its promotion of vegetarianism and exercise, formed a natural partnership with hydropathy, and the two often coexisted at water-cure institutions. Grahamites liked hydropathy because it was natural and did not involve drugs, which they, too, saw as unnecessary and harmful. Temperance advocates also found common cause with hydropaths, who shared their high regard for water as the only healthful beverage.84

All of these practices peaceably coexisted because unlike Samuel Thomson, hydropaths never enforced a dogmatic adherence to a strict theory and set of practices; all practitioners, more or less, agreed on the basics of the system but were free to carry them out however they saw fit. At Brattleboro, Dr. Wesselhoeft allowed small doses of regular medicine when used in combination with hydropathy. Mary Gove Nichols blended hydropathy with other theories and systems when treating patients. She allowed her patients to use homeopathy on occasion, figuring that dabbling in other irregular systems was always preferable to regular medicine. She herself had run a Grahamite boardinghouse in Boston before turning to hydropathy. While this flexibility allowed for much more personal interpretation and camaraderie among hydropaths and other reformers, it also undermined hydropathy in the end by minimizing the very things that made hydropathy unique as a healing system. A diversity of personalities and beliefs discouraged standardization and sometimes even led to practices that contradicted pure hydropathic theory.85 This became increasingly true as overall health hygiene—clean drinking water, waste disposal, sanitary housing—began to supplant water as the primary healer in the mid-nineteenth century. Hydropaths came to place as much faith in diet and exercise as water as the century wore on, a shift that removed the distinctive healing properties attributed solely to water. They gave up their systematic approach to water without offering an alternative means of advancing their principles. Without water, hydropathy lost its core value as well as its rationale for wrapping, bathing, and other water-related treatments.86

The hydropathic embrace of other therapies and novel ideas had its limits, though: most hydropaths ignored new discoveries and innovations in regular medical therapies and research, such as vaccinations, which cost them in the end. Scientific advances in the second half of the nineteenth century elevated the hospital and the laboratory to prominence, relegating self-taught and untrained doctors to the periphery of the emerging professional and scientifically oriented medical field.87 In a world that seemed increasingly complex, Americans began turning to experts to guide them. With hydropaths unwilling to distinguish between degree-trained practitioners and those who came to water cure by experience, they no longer appeared to be on the cutting edge of reform.88

Hydropathy also continued to resist national organizations and professional schools at the same time that regular medicine and even other irregulars were finding identity as cohesive and institutional powers. The Nicholses’ drive toward a professional education for hydropaths with the opening of their American Hydropathic Institute failed to gain traction. They operated the school for three terms and then abandoned it. Trall’s New York school suffered from low standards and a “woefully inadequate” staff, according to one chronicler.89 Other hydropathic schools opened in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, and Minnesota, but most closed quickly. Moreover, rigorous standards and formal training were contrary to the democratic tenets of hydropathy, so these educational efforts were handicapped from the start.90

To ensure a more secure economic and social position for themselves, regular doctors established medical societies and legislative standards aimed at excluding hydropaths from participating in the growing field of public health. Medical councils, hospitals, and city boards of health banned hydropaths from serving even as the issues they often addressed, like sanitation and green spaces, were much the same hygienic measures promoted for decades by hydropaths for health and healing. Hydropaths tried to fight back by criticizing regular doctors for taking the power of choice away from patients in deciding who could and could not practice medicine.91

Despite regular medicine’s refusal to recognize them as legitimate doctors, though, many of the hydropaths’ principles and innovations slowly became incorporated into regular medicine over succeeding decades. Advances in the germ theory of disease in the 1860s and 1870s led to an appreciation of bathing and overall cleanliness among regular doctors, who began to adopt and endorse the lifestyle recommendations long advocated by hydropaths. Bathing and staying hydrated with water appeared in a range of late-nineteenth-century health literature authored not by hydropaths but by new self-proclaimed experts in hygiene and public health maintenance. Later, in the early twentieth century, medical scientists also joined with public health proponents to address many of the issues that hydropaths and other hygiene reformers had long fought for like sanitation, diet, and exercise.92

The nation’s changing political and social culture also drowned hydropathy. The Civil War in particular brutalized hydropaths’ dreams of achieving individual and cultural perfection and harmony through their tenets of self-control and good health. They found that their idealism could not stand up against the harsh realities of a war that pitted Americans against one another.

The upheavals of the Civil War sped along shifting tides in popular culture as well. Following the war, what made for a good citizen changed. The self-denial and self-control that marked the early nineteenth century gave way to a more self-indulgent, pleasure-seeking, and consumer-oriented American people. Restraint and moderation, hydropathy’s unspoken mottos, were not the way to make a fortune in urban industrial America. Women also gained more public influence in other areas, eclipsing what had been a unique and empowering aspect of hydropathy. Many women joined a variety of social and political reform movements, including suffrage and labor activism, that invited the active participation of both men and women.93

Many water cures that survived the Civil War raised the temperature of their water and introduced gentler treatments to maintain their business. The increasing availability of in-home plumbing made the water cure less unique, so institutions added more non-water offerings to attract clients. Cures in Massachusetts and New York added billiards, dancing, vaudeville performances, and bowling. The cold-water cures also faced competition from luxurious resorts that catered to the conspicuous leisure of the wealthy and fostered a concept of health that was far more passive and recreation oriented—much more like the spas of old.94

Even with hydropathy’s decline, Mary Gove Nichols never stopped working and advocating for the causes in which she believed. In the 1850s the Nicholses turned increasingly from treating women’s illnesses to a more radical attack on what Mary believed to be the ultimate source of their troubles: marriage. Despite being happily married to Thomas, Mary never forgot the personal injury she suffered at the hands of her first husband. True marriage, she argued, came from love, not the legally binding strictures that largely left women powerless victims of their husbands. Thomas agreed. The idea of marriage as an institution outside the law was a real shocker in 1850s America, though, and earned the Nicholses branding as “free lovers.” Not to be confused with the 1960s idea, free love in the 1850s was a movement opposed to marriage, at least as an institution regulated by government. Many advocates equated marriage with slavery for the wife. Even among hydropaths, the Nicholses’ views on marriage were pretty far out there, driving them to the fringes of the main current of health reform. In 1861, at the outbreak of the Civil War, Mary and Thomas sailed to England and rode out the war abroad, publishing stories and articles that had little do with health, medicine, or hydropathy. After the war, they returned to health reform, operating a health resort in Malvern, England, the same town that hosted the institution of the water-guzzling James Wilson. They also wrote on medical topics, though without the overtones of free love that sank their reputation in the United States.95

At the end of her life, Mary joined the ranks of another health trend, mesmerism, and relied more on magnetic power than water to heal patients. She passed her hands over injuries and provided magnetized objects to patients that cured without physical contact. In 1882, Mary received a diagnosis of breast cancer and soon attempted to treat herself with the methods she had long advocated for others. Every morning and every evening she magnetized her body for ten minutes. Bathing remained integral to her routine, and she took almost daily baths for health. She also exercised regularly and maintained a Grahamite vegetarian diet. She practiced a little homeopathy. Through it all, Mary continued to see and treat patients until two weeks before her death on May 30, 1884, dedicated to the end to improving the health of humanity and the prospects of women—a truly visionary and progressive woman. Mary’s frankness on the physiology of women’s bodies and the constraints of marriage contrasted sharply with the prudery of her age.96

Hydropathy was not a complete failure: that Americans bathe regularly, drink lots of water, aspire to regular exercise, praise a low-fat and high-fiber diet, and wear nonconstricting clothing all reflect hydropathy’s early influence. These preventative health measures theorized and practiced by hydropaths in the nineteenth century became the foundation of modern healthy living still practiced and advocated by many nutritionists and doctors today. Few gyms, health and beauty spas, or athletic training rooms fail to provide users with some form of hydropathic therapy, be it a whirlpool, steam room, sauna, or swimming pool. The entire industry that exists in spas, Jacuzzis, hot tubs, and swimming facilities hearkens back to hydropathy’s insistence on the importance of water to human health. Water resorts, while no longer hydropathic, still promise vacationers relaxation and renewal, the same promises made by water cures. These destinations continue to attract visitors with their beautiful views, entertainment options, and flowing water.97

Perhaps hydropathy’s most visible legacy is in the popularly held belief in drinking eight glasses of water a day. This notion was appropriated and echoed with increasing fervor in the late nineteenth century by the temperance movement. By the 1910s and 1920s, American newspapers and magazines were filled with exhortations to consume eight glasses of water for health on a daily basis. Although scientists and doctors continue to disagree over how much water is enough, the idea of drinking fluids regularly for health remains undisputed.98

Although hydropaths appear not to have called disease “toxins,” their theory of using water to remove a disease-causing agent expressed this concept still very present in modern conversations about health. Today, many irregular therapies promise to flush toxins from the body through various methods, including water, in detox and cleansing diets and also advocate whole foods and exercise. The idea of flushing toxins likely predates hydropathy, but the system nonetheless provided a very clear articulation of an idea that became wildly popular and influential in irregular health.

Hydropathy also informed the reform movements that fought to clean up cities in the late nineteenth century. The emphasis of hydropaths on the importance of nature and fresh air in their treatments, and of renewal and possible perfection in the beautiful natural areas where they located their water cures, influenced the drive to create parks and green spaces in major cities. A visit to a park, like a stay at a water cure, was seen as the antidote to the ills of modern life. Efforts to improve city services for hygiene and to curb disease, particularly sewers and indoor plumbing, also have their antecedents in hydropathy.

Hydropathy lives on today as hydrotherapy and consists primarily of therapies performed in water, hot and cold packings for injuries, steam baths, foot baths, and wet compresses. Sebastian Kneipp, a German priest, is largely credited with reviving hydropathy in the late nineteenth century and transforming it into its modern form. Building on Priessnitz’s work, Kneipp added various water temperatures and pressures to the therapy regimen. Kneipp water baths, mineral bath salts, and other bathing products are still sold today. Hydropathy also plays a large part in modern sports medicine, which emphasizes the importance of water as an anesthetic, sedative, energizer, and aid to muscular exertion. Athletes often soak in ice-filled tubs after exertion to improve recovery, though some studies have questioned the efficacy of this practice, while other people use hot baths to ease sore muscles.99

What has changed between hydropathy then and now is the value attached to diet, exercise, and water. Today, these practices are less of a universal social good and more of a personal choice. None of the current rhetoric around spas, exercise, and drinking water offers to perfect humanity in the process, but it remains a primary means of self-improvement. Both today and in the nineteenth century, Americans’ near obsessive concern with physical fitness and health corresponded with a highly competitive, industrial life where fitness represented yet another asset with the potential to improve performance and individual advancement. This pursuit of fulfillment and meaning through health may represent an attempt at order and control in the midst of forces that seem large and unmanageable.100

So hydropathy’s decline did not mean the end of its principles and ideas. Much of what had once seemed strange and highly irregular advice—to exercise, drink water, bathe regularly, to breathe in fresh air—had become more widely accepted as common sense by the late nineteenth century among a broad swath of Americans, including regular doctors. Some hydropaths continued to practice while still others became homeopaths, joining what had become an increasingly powerful and organized challenge to regular medicine by the time the Civil War broke out. Both hydropaths and homeopaths condemned heroic therapies and believed in more natural remedies and clean living, but homeopaths would take their system to more mystical ends. They also became more powerful. Homeopaths converted untold numbers of regular doctors, opened dozens of medical schools, formed local and national associations, and published journals that rivaled and even bested much of what regular medicine had to offer, earning homeopathy regular medicine’s most vitriolic condemnation and the best chance of vanquishing heroic medicine.