In the archaic and classical periods, Greek and Roman histories broadly paralleled each other. According to legend, the city of Rome was founded in 753 BCE (about the same time as Sparta), as a kingship; the last of seven kings was reputed to have been overthrown in 509 BCE (almost exactly the same time as Cleisthenes was transforming the Athenian constitution). Following that overthrow, the Romans established the foundations of a regime better able to protect the res publica (in Latin, the ‘people’s thing’, in the sense of their affair or concern). The idea of the res publica has given its name in English to the Roman republic understood as a normative ideal, as the best constitution to protect and advance that common concern.1 In Roman thought, the common concern of the people included an emphasis on the concrete and material: what was publicum paradigmatically included collectively owned lands, revenues and provisions, generating the useful English translation of res publica as ‘commonwealth’.

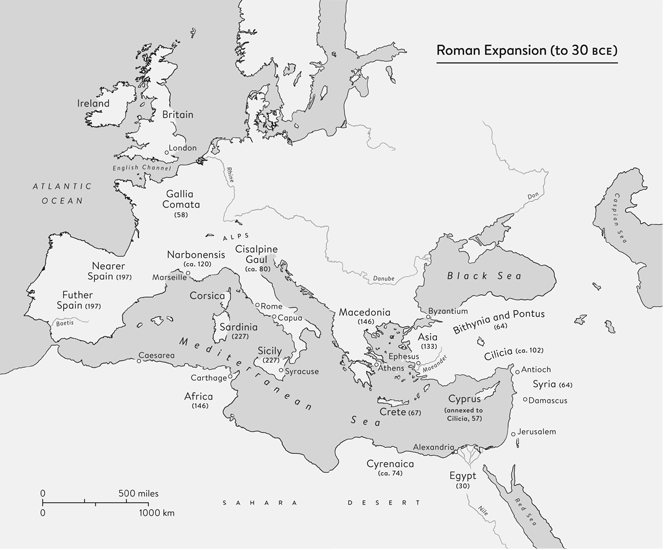

As initially established, the Roman republic replaced the king with two consuls, who exercised executive powers and military powers alongside a deliberative and advisory Senate (dominated initially by patrician aristocrats, eventually selected from the aristocrats and wealthy plebeians who had held high elected office) and a set of popular assemblies that variously elected officials, passed laws and carried out other functions as their convening magistrates set them to do. Over the next centuries, Roman history developed along two intersecting directions of change, which this chapter will explore. On the one hand, the constitutional arrangements of the republic continued to evolve, often prompted by social and political struggles between the nobility and the poor. On the other hand, the republic embarked on a remarkable series of military conquests, first within the peninsula of Italy, then Sicily and Sardinia, Spain, southern Gaul, Illyria and the Balkans and the Greek world more generally, and then further afield still. Concentrating their overseas conquests between 264, when the First Punic War with Carthage for control of Sicily began, and 146, when they destroyed the Carthaginian capital (now Tunis) and the Greek city of Corinth, the Romans would dominate the wider Mediterranean world for centuries to come. Their hegemony over Greek polities, in particular, brought Greek ideas flowing into Rome, and stimulated Roman thinkers to engage with the whole gamut of Greek history, literature and philosophy.

For all of its distinctiveness, the Roman constitution could be defined as a complex combination of the three basic Greek constitutional categories that we discussed in Chapter 2 and have found at work, often elaborated, in many analyses of Greek politics so far. More generally, all of the ideas that we have studied so far primarily in Greek societies and thought have counterparts in Rome, as a brief review of the relevance of each chapter so far to Roman thought will confirm. In Latin, the basic Greek question of whether justice and advantage could be reconciled or must remain at odds (Chapter 1) would be appropriated as a debate as to whether what it is honestas, or ‘honourable’, to do is ever at odds with what is utilitas, or ‘useful’, to the individual. The nature of equality – who counts as an equal citizen, and what political arrangements that entails – was for its part fundamental to understanding Roman politics. So, too, was the complementary value of liberty, which played a large role in Chapter 2.

Both Greek and Roman ideas of freedom, epitomized in the words eleutheria (Greek) and libertas (Latin), pivoted around the conceptual and legal opposition between freedom and slavery. These ideas of freedom could be applied to individuals and to the polity alike, expressing an ideal of independence from the arbitrary will of another individual, group or outside polity, and so related to the ideal of self-rule discussed in the form of Athenian democracy in Chapter 3.2 Virtue was conceived in Rome as a vital attribute of republican citizenship, as it was of citizenship for Socrates, Plato and Aristotle (Chapters 4 and 5). And the Roman constitution could be defended as resting on the Stoic law of nature, as it expanded to include so great a proportion of the known peoples of the time that it could be compared almost with the cosmopolitan ideal of certain Hellenistic philosophers discussed in Chapter 6 (a theme to be picked up in Chapter 8). Like Greek polities of the time, Rome cultivated civic shrines, rites and festivals, though citizens could honour other gods so long as they acknowledged and carried out the common rites.

Yet Rome was also in many important ways different from the Greek cities that we have so far discussed, even as its orbit expanded through negotiation and conquest to include those Greek cities themselves, and its political ideas included subtle innovations as well as variations on Greek models. Given the elaborate formulation of Roman law in practice and in the writings of the jurists who would chronicle and systematize it, legal vocabularies and forms of argument came to furnish especially influential ways of thinking of politics. Romans thought of the political unit as a civitas or a societas. Rather than battling over different kinds of regime for that community, they focused their political struggles (after the inception of the republican constitution) on what the law and the distribution of power should be within it. In other words, political struggles remained within the boundaries of a broadly accepted non-monarchical constitution, even as they effected in practice significant changes in its workings. Sometimes these struggles resulted in major institutional changes: above all, the establishment in 494 BCE of annually elected tribunes (originally two, later expanded to ten), who were able to defend ordinary citizens against violence to their persons and to seek to advance their collective interests. By contrast, attempts over several generations to redistribute, to the poor, public lands that had been appropriated, often corruptly, by the rich, were ultimately unsuccessful.

Despite the legal protections that they won over time, the political voice of the non-elite Romans was in significant ways far more restricted than at Athens, especially in the powers of initiative and accountability. The Roman idea of the republic stands as a model of a constitution that gives an entrenched political authority to a meritocratically chosen elite, alongside an important but partly defensive role for the poor. From a Greek perspective, Rome embedded an oligarchy into the heart of a democracy, even while it protected certain roles of self-assertion and moments of political decisiveness for the poor. The result is a distinctive regime. On the one hand, it may suggest new institutional mechanisms by which modern ‘democratic’ regimes can protect and even empower their poorest citizens;3 on the other hand, it raises uncomfortable questions about the extent to which those modern ‘democracies’ may similarly harbour oligarchical tendencies.

The politics of inclusion and exclusion in relation to citizenship were different in important ways as well. Roman slaves were property, as in Greece, but if they were freed by means of publicly registered procedures, they became citizens with only a few remaining civil disabilities, if also a lingering social stigma. Roman citizenship was gradually extended to pacify newly conquered or allied cities (sometimes originally without the right to vote, but that was gradually extended too), to the extent of there being some 900,000 adult male voters in the last decades before the advent of the principate (to be explained in Chapter 8). A Roman head of household (the paterfamilias) had extensive legal powers over slaves as well as women and children, including even adult sons. But it was possible for women in some circumstances to be emancipated from the need for male tutelage and to own property in their own names, and many women in practice played lively roles in commerce as well as in religious rites and social gatherings.

Observers at the time saw the Roman constitution as distinctive in being a special combination of the three simple Greek constitutional types (one / few / many) introduced in Chapter 2. Rome was seen to be like Sparta in not fitting neatly into any one of these categories, drawing its strength instead from its balancing of elements of each. And what strength it was! Rome had risen to an unparalleled dominance by the middle of the 2nd century BCE, the point at which the first major observer and analyst of its political life whom we will consider (Polybius) encountered it. After looking at his account of the Roman constitution, we will turn to an analyst and participant in Roman life a century later: Cicero. While Polybius will introduce us to Rome through the eyes of an observant Greek marvelling at its rise to geographical hegemony, Cicero will provide a distinctive account of the nature of the res publica from within the tumultuous history of the 1st century BCE, in which the republican allocation of power was repeatedly threatened and ultimately permanently transformed.

Meet Polybius

The question that Polybius thought must, and should, be preoccupying his readers was simple: ‘How, and with what kind of constitution, almost the whole inhabited world was subjected and brought under a single rule, that of the Romans, in less than fifty-three years?’4 He was referring to the ‘less than fifty-three years’ from 220, when the Romans had annexed the Po region of Italy in the course of their rivalry with Carthage (today Tunis, in Tunisia), to Rome’s smashing of the kingdom of Macedon in 168 BCE. That was the timespan that he originally set out to document in his Histories; he would eventually carry the narrative on through 146, the year in which Roman armies sacked both Carthage and Corinth, doing away in a single year with its greatest rival (the Carthaginian general Hannibal had inflicted a shocking defeat on Rome in 216 at Cannae) and with the independence of the cities of mainland Greece. The expansion of Rome had actually begun well before, with the conquest of the other inhabitants of the Italian peninsula below the Po valley; the occupation of Sicily, Sardinia and Corsica in the teeth of Carthage; and power plays that led to Roman domination and influence, expressed in varying ways, over most of the Mediterranean world and beyond.

HIGHLIGHTS OF ROMAN HISTORY DISCUSSED IN THIS CHAPTER

| 753 BCE | Legendary founding of Rome by Romulus |

| 509 BCE | Founding of the republic: overthrow of last king, replaced by two annually elected consuls |

| 5TH CENTURY BCE | |

| 494 BCE | Tribunes of the plebeians established |

| 451–449 BCE | Twelve Tables – basis of Roman law |

| 3RD–2ND CENTURIESBCE | |

| c. 200–c. 118 BCE Lifespan of Polybius | |

| 146 BCE | Roman conquests of Carthage and of Corinth |

| 133 BCE | Tribune Tiberius Gracchus attempts land reform |

| 123, 122 BCE | Tribune Gaius Gracchus attempts similar reforms |

| 2ND – 1ST CENTURIES BCE | |

| 106–43 BCE | Lifespan of Cicero |

| 63 BCE | Cicero becomes consul; exposes Catilina |

| 44 BCE | Julius Caesar assassinated (‘Ides of March’) |

| 43 BCE | Cicero assassinated |

| 27 BCE | Octavian made Augustus Caesar |

Polybius appointed himself the task of answering that question, by writing a history not of Italy or Greece or Egypt alone, but a ‘universal history’ (5.31, 5.33) befitting the rise of Rome through combat or negotiation with virtually all the other powers known to it at the time. He was extraordinarily well qualified by his remarkable life circumstances to do so. He was born around 200 BCE in the relatively recently founded city of Megalopolis (for which a Peripatetic had written the constitution, as we saw in Chapter 6), to a leading family in the Achaean League, a federation of Greek cities in the Peloponnese.5 At the time of his birth, the league had succeeded for some decades in managing its relations with the rising Roman power with sufficient finesse to enjoy a good measure of meaningful political independence. The constituent cities of the league called themselves ‘democracies’, meaning that they were not tyrannies or oligarchies, and that all citizens were entitled to attend the ordinary and extraordinary assemblies that made league policy. But they were moderate regimes very different from classical Athens, say, in affording a larger role in practice to their elites, while empowering their poor to a much lesser extent. They did not pay poor citizens for attending the rotating assemblies of the league, for example, meaning that in practice relatively few would participate. In accordance with this political culture, and like his predecessor as an historian, Thucydides, Polybius was critical not only of tyranny (e.g., 5.11, contrasting tyrant with king), but also of unbridled democracy (which he called an ochlokratia, or ‘mob-rule’, 6.57).

Son of a statesman active in the league, belonging to a family privy to the high councils of diplomacy and frequently playing host to Roman and other foreign guests, Polybius rose to the high office of ‘hipparch’ (cavalry leader) for the federation. But in 167 he was among some 1,000 Achaean citizens whom the Romans seized and held in Italy in the course of a dispute about alliance politics, on the pretext of needing to investigate their denunciation by a pro-Roman fellow citizen. Most of his fellows were kept in provincial peninsular towns where they could not cause trouble. But, perhaps due to family connections, Polybius managed to move to the very heart of Roman urban society and to spend most of what would turn out to be his seventeen years as a hostage there. He became attached as a tutor to the family of Scipio Aemilianus, who would rise to become a successful consul and general, leading the final assault on Carthage in 146 BCE. Polybius watched as those inhabitants who survived his friend’s siege were sold into slavery and the conquered city was set alight and left to burn. Afterwards he took a boat and explored up and down the west coast of Africa (he was an intrepid traveller, having already retraced Hannibal’s journey through the Alps). Meanwhile, in the same year, other Roman troops destroyed the Greek city of Corinth, dissolving the Achaean League and the democratic constitutions of its member cities, including the city in which Polybius had grown up and served as an official as a young man. Polybius, brought in to mediate a political settlement with Rome, was rewarded by both sides, with heroic statues of him erected across the Peloponnese. He would undertake further travels with Scipio Aemilianus and the Roman armies, for example probably witnessing and certainly writing an account of the destruction of Numantia in Spain in 134–133 BCE, which was an important moment in the Roman expansion to the west.6

Polybius had already started to write his Histories while still a hostage. What was perhaps initially designed as a guide to inform his fellow Greek political leaders as they sparred with Rome would become a chronicle and analysis of Rome’s ultimate triumph and its ways of exercising power. As an outsider with unparalleled access to the inside of Roman senatorial politics, steeped in Greek history and philosophy but living long among Greece’s Latin-speaking conquerors, he was in an excellent position to provide an account that tells us a great deal about Rome through the lens of Greek constitutional analysis. We will pay attention to what this lens led him to downplay or exclude, as well as to what he so richly included.

‘In less than fifty-three years’: Explaining Rome’s Rise

Polybius, who was conversant with the works of Thucydides and Plato, held that states succeeded or failed most fundamentally due to their constitution, or politeia. Thucydides had contrasted Spartan stability with Athenian expansionism. According to the Athenian historian, the uniquely austere laws framed by Lycurgus had made Sparta’s domestic constitution stable, but the boldness cultivated by Athens led to its imperial aggrandizement, which was, for a time, more successful. Plato, for his part, had told a story of constitutional change in the Republic, Book 8, which depicts an ideal regime degenerating into a ‘timocracy’, literally, a regime prizing honour and military victory, associated by Plato with Sparta; then into an oligarchy prizing wealth; then into a democracy prizing freedom; and finally into a tyranny prizing the satisfaction of the tyrant’s basest appetites. Later historians and philosophers had offered less stylized accounts of constitutional changes, exploring how oligarchic luxury and arrogance might generate democratic envy and resentment. Aristotle, for example, as we saw in Chapter 5, traced sequences of constitutional change generated by various types of motivation among different groups. To these variations on the classical themes of constitutions governed by one, few or many, either well or badly, the post-classical Epicurean school explored in Chapter 6 had added an emphasis on the original desire for security, which they saw as having prompted the development of laws and constitutions.7

Drawing on the classical schema of one/few/many and the Platonic idea of a characteristic sequence of constitutions, Polybius integrated these with his own vivid dramatization of polities as living organisms that are bound eventually to die. The result was his famous account of a natural cycle of constitutional change that is bound to recur. Humans in a primitive state – a state not confined to prehistory, but one that natural catastrophes like floods or earthquakes may repeatedly produce – will, like animals, follow the strongest leader, the condition of despotism. But in associating together, their natural powers of reason will begin to produce ideas of gratitude, honour and justice, and, most fundamentally, utility (Polybius, on this point, was influenced by the Epicureans), so that they start to conceive of their leader as a king who benefits them rather than simply as a despot of whom they are afraid. Hereditary kings, however, inevitably become corrupt, turning into tyrants, who are then deposed by leading nobles, who establish aristocracies. But the aristocrats become corrupt in their turn, degenerating (as in Plato) into avaricious oligarchs, and it is the common people this time who revolt and establish democracies. Yet corruption will inevitably set in once again, in the person of greedy and ambitious nobles who bribe the common people, until eventually the democracy will be convulsed by massacres and destruction – and despotism will reign again.

So far, so Greek, indeed in many ways so Platonic, though Polybius emphasizes the idea of a natural order of growth and decay more than Plato had done (and the orders of their sequences somewhat differ). But what makes his work most innovative is what happens when he turns to the case of Rome, comparing it with Sparta. For he argues that the instability of each regime in the natural cycle is exacerbated by its unmixed, simple character. A simple oligarchy, for example, has obvious vices, such as the greed of its leading men, and these put it on a straight path to decline, like the rust that naturally corrupts iron (6.10, discussing Lycurgus’ avoidance of this fate for Sparta). But there is a way to sidestep the inevitability of such flaws. This is to establish an equilibrating constitution that can balance the virtues of each kind of constitution, correcting its characteristic vices with the virtues of another kind. Lycurgus did this for Sparta through his legislative wisdom; the Romans did it for themselves through experiment and conflict. An equilibrating constitution can stave off decline, at least for a very considerable period – long enough to explain Rome’s remarkable political ascendancy. It can perch outside the cycle of constitutions, stable and flourishing – perhaps for decades, perhaps for centuries, though ultimately all cities, like natural beings, must die.

To be sure, Polybius found some precedent for the idea of a ‘mixed constitution’ (as this idea in his work is often described)8 in brief discussions in Thucydides, Plato and Aristotle. Thucydides describes the rule of the Five Thousand in Athens – a short-lived successor to the oligarchic coup of 411 BCE – as a ‘moderated mixing’ of the few and the many.9 In Plato’s Laws, Sparta is presented as curbing the arrogance and potential corruption of power partly by Lycurgus’ having ‘blended’ the kings with a council of elders, followed by the establishment of the board of five annually selected ephors to put a ‘bridle’ on the government (the language of ‘bridling’ suggesting an external check rather than an internal blending).10 The unnamed elderly Athenian man who leads the discussion in the Laws offers a more general lesson: that in legislating one must mix together the two ‘mother-constitutions’ of monarchy and democracy for a constitution to be good and stable.11 Aristotle in his Politics focuses rather on the mixing together of oligarchy and democracy as a practical recipe for political stability (as we saw in Chapter 5).12 All of these classical-period writers treat a ‘mixed’ constitution or regime primarily as one in which two constitutional forms – either in the sense of their characteristic institutions or their dominant social groups – are blended together.

While picking up on this classical idea of combining simple constitutional forms, Polybius was more interested in balancing than in blending. In his analysis (perhaps following that hint about the ephors as a ‘bridle’ in the Laws), the mixed constitutions of both Sparta and Rome work by playing off monarchical, aristocratic and democratic elements of the constitution in an ongoing dynamic balance – even a struggle – in which each is responsible for checking the others. This is the most influential source of the idea of checks and balances that would fascinate later republicanism and political theory, as taken up especially by 18th-century French political thinker Montesquieu and by the American founders.13 Polybius describes it succinctly in the case of Sparta, crediting Lycurgus with designing the constitution so that ‘each power being counter-balanced by the others, none of them should determine the inclination or do so for the whole, but being equally balanced and equilibrated according to the principle of opposition, the governing body will continue in permanence forever’ (6.10).

Such delicate balancing might seem necessarily to result from artifice, from deliberate human invention. Yet the Romans, Polybius claims, have attained a mixed constitution ‘not … through reasoned argument [in contrast with Lycurgus], but through many struggles and experiences, constantly drawing the best solution from the learning gained from these trials’ (6.10). Just as the Greek constitutional analysts scratched their heads over Sparta – did its two kings make it a kingship, or its council of elders (the gerousia, literally ‘body of the elderly’, who were elected for life) make it an aristocracy, or its strictly limited citizenship make it a democracy? – so, too, Rome cannot be easily pigeonholed into the simple forms of Greek constitutions: ‘no one, not even those of that land themselves, would be able to say with certainty whether the governing body as a whole is aristocratic or democratic or monarchical’ (6.11). Polybius’ fellow Greeks might be inclined to hold up their noses at Rome, a constitution without the benefit of a founding legislator, but that would be a mistake. The Romans have by experience and struggle attained an acme of constitutional excellence comparable with that bestowed by the most revered legislator of Greece.

The Three Parts of the Roman Constitution

How did Polybius come to view Rome as an equilibrating constitution? He identifies each of three elements in turn as candidates for being the ‘greatest part’ of the constitutional governing body, only to show how each is dependent in practice upon the others. Since none of them can act so unambiguously as to be said to be unqualifiedly dominant, none of them can rightly give its name to the overall constitutional form (as a dominance of the demos would make a regime a democracy). Instead, it is in the balancing of their different roles and powers that the constitution as a whole takes shape. Polybius demonstrates this by examining the elements of the Roman constitution embodying kingship, aristocracy and democracy in turn. He shows that none of these can account for the complex balancing of different sources of power that Rome actually evinced (as he saw it: his observations themselves reflect his particularly Greek theoretical outlook). Each might try, but none in practice could succeed in overbalancing the others so thoroughly as to merit calling the regime exclusively by its name. In other words, Polybius shows that Rome cannot fairly be described as kingship, aristocracy or democracy; it is instead a complex constitution consisting of the balanced competition of all three.

Consider first, as Polybius does, the consuls. These are the candidates who would constitute a monarchical or despotic principle in Rome. The question is whether their power is so great as to warrant considering the constitution a kingship (it can’t literally be a ‘monarchy’, as two consuls served in office simultaneously and collegially). Polybius’ evidence for considering the consuls in the light of kings is the fact that they were believed to have inherited their powers of imperium, which meant strictly their military command, though the term was sometimes used in a wider sense for general power.14 To make the provisional case for the consuls’ making Rome count as a kingship, Polybius says that they give orders to the other magistrates. (In reality, each magistrate had his own sphere of duties, so this hierarchical ordering was less clearly a relation of command than its portrayal in Polybius.) He also claims that the consuls organize all military preparations and command the armies in the field; and they play a role in setting the agenda for the Senate and (some of) the popular assemblies, and execute their decisions (6.12). And they could order the expenditure of public monies for the purposes that are theirs to carry out.

Nevertheless, it is hard to see annually elected officials who were subject to accountability procedures at the end of their term as plausible embodiments of the principle of kingship. And, indeed, Polybius concludes that the existing form of the res publica should not be described as a kingship. He points out that each consul’s exercise of power will be subject to a financial audit at the end of his term and to an oath swearing to have obeyed the laws in general, which can be challenged by prosecution in popular courts (albeit not organized in the same way as the lottery-selected courts of Athens). Moreover, while each consul enjoyed full imperium over his own troops while in the field, drawing money to feed them had to be authorized by the Senate. Indeed, a consul’s very sphere of military activity was decided by the Senate, which set each one in charge of a particular province or military campaign. And while outside the city on campaign, he could not at the same time exercise his consular powers at home. In short, despite the elements of kingly power that had been transferred to the consuls, Rome could not, in Polybius’ view, be plausibly described as a kingship.

Apart from the purposes of exercising their Greek constitutionalist muscles, no Roman would have been inclined to describe the res publica as a kingship. The Romans presented their public actions as the work of the ‘Senate and People of Rome’ (Senatus Populusque Romanus), and it is S.P.Q.R. that is engraved on the monuments of republican rule. No Greek council had been nearly as significant, with the possible exception of the Spartan gerousia – whose members served, like the Roman senators, for life (in the middle republic, the senators were selected from among those who had held the higher magistracies). Was Rome, then, best described as an aristocracy, in virtue of the Senate’s important role within it?

The Senate had originally been the preserve of elite kinship groups. But, over time, wealthy plebeians joined the elite, and together with the original patricians they comprised the nobility. Meanwhile, the Senate’s membership became restricted to the ranks of those who held or had held the higher magistracies. Still, it was that aura of elite status that gave the Senate much of its sway. For, as Polybius points out (and contrary to later theories of the balance and division of powers), the Roman Senate had no power to legislate, all power to do so belonging to the people. Instead its powers were deliberative, investigative, managerial and advisory. The Senate used its powers of deliberation in managing public funds (apart from those specifically assigned to particular magistracies); investigating public crimes; and handling foreign relations. Probably after Polybius had finished his history, the Senate began occasionally to issue a kind of decree called (albeit only twice in surviving sources) senatus consultum ultimum, advising certain magistrates ‘to see to it that no detriment befall the commonwealth’, a decree that put the Senate’s weight behind those magistrates to encourage them to do what they might judge necessary – even if not wholly according to law – to preserve the republic.15 Before and beyond such decrees also, the Senate carried an important gravity and weight. Yet, for all the deference and authority that it enjoyed, the Senate, too, could be checked, in ways demonstrating that the res publica could not well be judged to be a simple aristocracy. As Polybius notes, the tribunes of the plebs (elected by the non-noble plebeians only) could block any senatorial decree and could even bar the Senate from meeting altogether. The people, in their lawmaking capacity, could also more broadly reshape the Senate’s prerogatives.

Given the importance of the popular assemblies’ unique capacity to pass and repeal laws, asks Polybius finally, should Rome be termed a democracy? This is a question that has recently been revived by scholars, with some coming close to saying yes by emphasizing the importance of the democratic element in the constitution.16 Polybius, like these recent scholars, notes that the power to legislate remained solely in the hands of the people throughout the republican period (indeed long into the imperial era). Only the people could pass or repeal laws. The power to make laws also extends into a power of setting other fundamental parameters for the existence of the republic: the people have the sole power of making peace or war, and of ratifying treaties and alliances, issues that would be put to them upon recommendation from the Senate. Polybius links this further to a more general role of what he calls the Roman demos (in Latin, this would be the populus) as being ‘sovereign [kurios] in the politeia over honours and penalties’ (6.14). By ‘honours’, he means primarily the elections of magistrates, and the conferring of every grant of imperium by means of a lex de imperio; by ‘penalties’, he means judicial cases involving the death penalty and heavy fines. (Polybius said relatively little about the powers of the tribunes, who had no exact equivalent in Greek constitutional theories.)

Should these substantial popular powers be enough to classify the state as a ‘democracy’? Against that suggestion, supported by some later scholars, others have noted that the power to pass laws was not the power to frame them. No one had the right to propose a law to a popular assembly except a magistrate or a tribune, and no one had the right to speak in a voting assembly at all; even in those assemblies called for discussion without decision (contiones), no one had the right to speak unless called upon by the presiding magistrate or tribune. (Contrast Athens, for example, where the council setting the agenda for the assembly was selected by lot, and where anyone who wished could speak up in an assembly.) Roman popular assemblies themselves took several different forms, but in all of them votes were cast as a member of a group, whose position was itself determined by majority vote. In one kind of assembly, the groups were called forward in sets determined by status and wealth (they originally correlated to military rank), meaning that some of the later groups would never even get to vote before the question had already been decided. In another, citizens were allocated to another set of groups in ways that made some more highly populated than others, so diminishing the relative influence of individuals within the larger groups.

Polybius’ own answer likewise denies that Rome was best described as a democracy, despite the significant role of the people within its constitution. But he draws on different features of the constitution to make his case. He balances the people’s sovereignty over honours and penalties, laws, war and peace, with their dependence on the Senate for financing public works; the judicial role in civil suits played by senators; and the subjection of individual soldiers (who, until 107 BCE, were conscripted only from those above a certain property threshold) to the imperium of their generals.

Thus Polybius concludes that Rome should no more be classified as a democracy than as an aristocracy or a kingship. Instead, it should be construed as an equilibrating constitution among the three parts that incorporate those tendencies, one that protects the liberty of all of its citizens through the very process of overreaching and adjustment:

For when any of the three parts swells up, becoming intoxicated with winning and with exercising power beyond what is appropriate, it is clear that – none of them being self-determining as the argument so far has shown – each has the power deliberately to counter-balance and catch hold of the others, so that none of the parts is able to swell up or to become overly disdainful (6.18).

Yet the historian believed that even Rome would eventually become unable to ward off corruption, bitter rivalry for power and popular ambition (6.57). He describes that degeneration in deeply Platonic terms, envisaging that Rome would eventually become a constitution called a democracy (demokratia), a name hiding its actual nature as a form of ‘mob-rule’ (ochlokratia, 6.57), one that would ultimately fall prey to despotism in the next turn of the cycle of constitutions.

For Polybius, it is primarily these features – what we might call the checks and balances – of the Roman constitution that answer the question he originally asked: how has Rome been so unprecedentedly and overwhelmingly successful in its imperial expansion? While Polybius classified the Roman constitution in Greek terms with this equilibrating twist, the most influential Roman analyst of the constitution would go further in investigating the internal connections within that constitution between liberty, property, justice and natural law. If Polybius was our guide to the Roman republic’s rise to its zenith, we turn now to Cicero, writing in the later part of the republic’s tumultuous history.

For almost the whole of the 1st century BCE, Rome was shaken by repeated waves of threat and civil war, as individual generals used their armies abroad to manoeuvre for greater forms of power at home, transforming the scope of the various political roles that they and others held either by passing new laws or by bestowing new powers on themselves by bending or breaking the laws. A first wave of civil war in the 80s resulted in Sulla making himself dictator; the patrician Catilina conspired against the republic in 63; the breakdown of an erstwhile alliance of three strongmen in the 50s resulted in Julius Caesar’s invasion of Italy in 49 and a renewed bout of civil war; Caesar was assassinated in 44, but his aides and heir were able to seize power, with an eventual final struggle between Mark Antony and Octavian (Caesar’s heir) being decided in the latter’s favour at the battle of Actium in 31, after which he was able to consolidate power while restoring republican forms, as we will see in Chapter 8. Cicero’s lifetime encompassed the bulk of this traumatic period of Roman history, and he was a political player in many of these events as well as a philosophical interpreter of what the republican constitution meant.

Meet Cicero

As a young man, Cicero left the city of his birth (in 106 BCE) in the south of Italy – where his family were among the lesser landowners in a town that had received full civic rights only relatively recently – to pursue philosophical studies in Rome and Athens, before returning to Rome to embark upon a political career. Despite a ‘harsh and unmodulated’ voice,17 he made his name as a lawyer, beginning with the prosecution of a corrupt governor of Sicily in 70 BCE, and also serving as a defence attorney even as he rose up the cursus honorum (the scale of honours as a magistrate) through sheer brilliance and ambition. His triumph in being elected one of the two consuls for 63 BCE, despite his less than exalted birth and at the youngest legally possible age of forty-two, would prove a fine and yet also a fateful hour for his career.

As consul he exposed a conspiracy led by the patrician Catilina against the republic, but then suppressed it brutally and arguably illegally by putting the ringleaders to death without trial. That act would shadow the immediate glory he had been accorded as ‘Parent of His Country’,18 driving him into exile for a time, even though he himself touted his acts for saving the republic: ‘when I held the helm of the republic, did not arms then yield to the toga? … What military triumph can stand comparison?’19

Having returned from exile, Cicero found himself still gallingly excluded from public affairs. He licked his wounds in philosophical composition from 55 to 51 BCE, producing three of his most important works of political philosophy: the De Oratore (On the Orator), De Re Publica (On the Commonwealth/Republic) and De Legibus (On the Laws) – all modelled stylistically and thematically on Platonic dialogues. He was then given the governorship of a province for a year, in which he could again put some of his theories and ideas into practice. As the republic began to tear itself apart, with powerful men jockeying for power in vertiginously shifting alliances, his position became awkward with the triumph of Julius Caesar in the civil war and his being proclaimed Caesar ‘dictator’ in 49 BCE. (The dictatorship was an office that Roman history and constitutional practice recognized and occasionally conferred, bestowing emergency powers upon one man that allowed him to abrogate other offices and laws for a limited period.) Cicero and Caesar had a complicated relationship compounded of mutual admiration for philosophical and rhetorical abilities, and mutual opposition for most of the time in their political aims. Cicero spent the two years after Caesar’s victory in strategic retirement at his country villa, during which he engaged in his second bout of concentrated philosophical production.

Cicero was not invited to participate in the conspiracy to assassinate Julius Caesar in 44 BCE; the conspirators ‘feared both his nature, as lacking in daring, and his age’ (Cic. 42.2).20 But after the assassination took place, Cicero defended it in a coded form in his De Officiis (On Duties), written some months later in just a few weeks, just as he was also penning the Philippics castigating Caesar’s aide Mark Antony, who was seeking to capture public opinion and power in the wake of Caesar’s death. On account of his hostility to Antony and his miscalculations about the loyalty of others, Cicero himself was murdered in 43 BCE on the orders of the Second Triumvirate (Antony, Lepidus and Octavian: the last of these would sixteen years later become Augustus). His head and his hands were cut off for public display – a warning to other enemies of the new order who harkened back too longingly to the old.21

Unlike the more fragmentary remains of the Hellenistic philosophers, which he had studied (being strongly influenced by the Sceptics and Stoics, and also by Plato, while opposing Epicurean claims), Cicero’s speeches, letters and other writings have been passed down in abundance, though not all are intact and others are lost. We know a good deal about his personal life (he divorced two wives, and was devastated by the death in childbirth of his beloved daughter Tullia),22 and about his work as a lawyer and a politician (his exchange of letters with his brother includes the latter’s instructions on how to win Roman elections).23 His political identity was above all that of an orator, one who allied philosophy to rhetoric in his practice, and who also wrote philosophical dialogues and studies, especially at times when he found himself unable to devote himself to public affairs.

The Romanness of Cicero is nowhere more evident than in his understanding of oratory. Defending his own profession in De Oratore, he insists, in bald opposition to Plato’s Gorgias, that rhetoric is a genuine art, a branch of knowledge, and indeed the supreme art, above even philosophy.24 The rhetorician is no trickster or shyster; he is the fount of good mores (customs and habits), who is uniquely able to instil virtue in his fellow citizens. Cicero assigns expertise in oratory the highest role in enabling him to fulfil his sacred duties to the republic. While philosophy was valuable and important, any man who failed to respond to his country’s call because of its blandishments, or who disdained to use rhetoric when it was called for in place of pure logic, would be a failure as a man because he was a failure as a citizen.

Cicero would write in his own voice that experienced statesmen are wiser than ‘philosophers who have no experience at all of public life’, and celebrate the value of political life: ‘there is nothing in which human virtue approaches the divine more closely than in the founding of new states or the preservation of existing ones.’25 Writing philosophy, and contributing to the forging of a Latin vocabulary and discourse grappling with Greek philosophical ideas, was a way to contribute to the republic when more direct political ways were barred, as well as a personal consolation and source of satisfaction.26 Cicero’s corpus of philosophical texts, together with his speeches and letters, reveal the world of a man concerned to inform and justify his actions in the terms he and others had developed in their engagement with Greek philosophy, while acting at the highest levels of Roman politics.

Cicero on the Roman Constitution

Polybius had provided an analysis of the Roman constitution written in the course of his friendship with the 2nd-century consul Scipio Aemilianus (the conqueror of Carthage whom we met earlier), an analysis that Cicero and his contemporaries studied closely. Perhaps in homage to Polybius, Cicero puts his own account of that same constitution – embedded not in a history of Rome’s rise, but in a Platonic-like dialogue – in the mouths of Scipio Aemilianus and his circle, in the year 129 BCE, a turning point in the history of the republic roughly two decades before Cicero’s own birth. Four years before the dialogue’s dramatic date of 129, Tiberius Gracchus had been elected tribune and had proposed a law to redistribute a body of public lands (lands that had been acquired by the republic by conquest or bequest, and that had been appropriated largely by nobles, often corruptly, for the payment or sometimes non-payment of a low tax) to the landless poor. In the process, he had illegally demoted a fellow tribune who had vetoed the measure. A group of senators, who identified themselves as standing for the interests of the optimates, or ‘best men’, strongly opposed that demotion together with the land redistribution itself. Led by Scipio Nasica, a cousin and associate of Scipio Aemilianus, that opposition group carried out the murder of Tiberius Gracchus and the subsequent undoing of the laws he had championed.

By making Scipio one of the main characters in his dialogue, charged with presenting the arguments in favour of each of the simple forms of constitution and then defending the ‘mixed’ constitution of Rome as best, Cicero exhibits his solidarity with the optimates, who identified Roman liberty overall as resting crucially on the prerogatives of the Senate and on a view of property that dictated a rejection of land redistribution. The historical Scipio, who is presented as Cicero’s spokesman for this part of the dialogue, had died a few days after the dialogue’s dramatic date. Thus the dialogue (surviving only in fragments) is cast as an elegy for a man who might have helped to avoid the further tumults that convulsed the city in subsequent years, including a second attempt at land redistribution by Tiberius’ brother Caius Gracchus, who would be driven to ask a slave to kill him in the midst of an outbreak of violence against this attempted reform.

Whereas Polybius had presented his analysis of the Roman constitution by asking which of the simple forms of Greek constitution it might resemble, Cicero sets his in the more Platonic context of a question about the optimum statum civitatis (1.33): the best condition, or form, of the commonwealth. Scipio is asked to recall his former discussions of this topic with Polybius and another Greek philosopher, in order to explain his view that the constitution inherited by the Romans of their day is actually that best condition. He begins by explaining just who the ‘people’ are who figure in the definition of a res publica as the people’s thing or affair. A people is not just any group or gathering of human beings whatsoever, but ‘a collection of a mass which forms a society by virtue of agreement with respect to justice and sharing in advantage’ (1.39).27

The question is then under what kinds of constitution a res publica – understood in the legal terminology that permeated Roman philosophical argument to be a thing over which the people enjoy certain rights that they may choose to entrust to others – may be enjoyed and protected. Scipio allows that this is possible under all three non-corrupt Greek models. Even in a monarchy, it is possible for there to be sufficient concern for the people’s interests and for what they are owed (we may use ‘rights’ to describe this, though Cicero tends to use the singular), though he concedes that this does not give enough credit to the general understanding of what the people want to possess in possessing the res publica. Scipio then sets out the Polybian-type claim that even where each of the three basic types of constitution is well governed, each has a characteristic flaw, lacking due provision for the characteristic goods provided by the others (1.43). In a monarchy, no one but the king enjoys a share in justice and deliberation; even under a wise and just king, it is hard to argue that a simple monarchy is a very desirable res publica, or ‘people’s thing’, at all. In an aristocracy, by contrast, the people have scarcely any participation in ‘liberty’. And in a democracy, even when the people rule justly and moderately, the equality enjoyed is actually ‘unequal’, since it fails to recognize different degrees of dignity (he is doubtless implying the kind of dignity rightly, in his view, enjoyed by the Roman senators, for example).

Having surveyed these three types, Scipio then presents his own opinion that the best condition of a commonwealth consists of a fourth type: one that is measured and mixed from the original three (1.45; see also 1.69).28 Like his real-life tutor Polybius, he argues that this, happily, is the very condition into which Rome has evolved through the practical experience and statecraft of many generations – indeed, he goes further by claiming that only Rome, not even Sparta or Carthage, has achieved such a mixed constitution, a point he illustrates by offering his own version of the Polybian cycle of regimes. Scipio is said by Augustine to have summed up his argument at the end of the first day of reported dialogue with this claim: ‘What the musicians call harmony with regard to song is concord in the state, the tightest and the best bond of safety in every republic; and that concord can never exist without justice’ (2.69a).29

Property, Justice and Law

While Scipio’s endorsement of justice as the basis of civic concord is deeply Platonic, when he and his friend Gaius Laelius come to discuss the institutions, mores and laws that can foster a true commonwealth, they chastise Plato’s Republic and Spartan customs alike. This is because they see the Platonic and Spartan constitutions as involving a flawed and dangerous understanding of political community: to wit, as based on property held in common rather than privately. The discussion of these topics in De Re Publica hardly survives, however, and so we must turn to Cicero’s other writings to reconstruct his defence of private property and its political implications at the time. Looking at his speeches, we find that he engaged in a reprise of the debates over the land reforms of the Gracchi that form so stark a background to the De Re Publica that he would later write. In 63, one of the newly elected tribunes proposed a new form of agrarian law, which would use an unusual and partial electoral procedure to establish an independent commission with powers to sell, tax, and use various categories of public lands so as to distribute land in Italy among the Roman poor.30 Cicero, as consul in 63, made three speeches against this proposal, one before the Senate and the other two before popular assemblies, which he chose to publish three years later as another effort of land reform was under way.

Cicero attacks primarily the form rather than the substance of the agrarian law proposed in 63: that is, he says less about the benefits and disadvantages of distributing land per se, and more about the arbitrary and tyrannical authority by which it was (he argued) proposed to be done. It is arbitrary insofar as the commissioners would be immunized against any legal challenge: he claims that they will be able to name any property they choose as public property and then to sell it as they wish. This, he urges his fellow senators, will be a threat to their own safety and liberty and dignity. And he argues to the people that the law would also undermine the peace, liberty and leisure that they enjoy, depriving them of their ‘right of voting’ (because of the irregular voting procedure, allowing only a randomly selected subset of voting units to elect the commissioners), and by doing so would deprive them of their ‘liberty’ (2.17, 2.16).31

To fill out Cicero’s views on the importance of law and of property respectively, we can turn to still other writings. He presents his fullest account of law in the dialogue De Legibus, a dialogue that, although he began to write it in the same year that De Re Publica was published (the year in which he himself was serving as governor of the province of Cilicia, 51 BCE), is set in a very different dramatic context. Its protagonists are not admirable ancestors but he himself (as ‘Marcus’), his brother Quintus and his closest friend, Atticus, depicted as talking together at his country estate in Arpinum and discussing the nature of the civil law. This brings them to imagine an ideal law code suitable for the mixed commonwealth of Rome that had been defended in the earlier dialogue.32

Caustic about the petty details (‘party walls and gutters’)33 on which Roman jurists concentrate when they should be considering the fundamental nature of the laws, Marcus insists that law is the embodiment of reason. To understand this, one must move beyond particular written laws to ‘seek the roots of justice in nature’.34 This approach exhibits the Stoic inclinations that Cicero often expressed in his writings about ethics and politics, inclinations to be understood in the context of his moderate Scepticism, which allows him to find certain views more probable than others. Because humans share reason and so this fundamental law with the gods, ‘this whole world must be considered to be a common political community [civitas] of gods and humans’35 – a statement invoking the Stoic Cosmopolitan ideal discussed in Chapter 6.

Marcus makes the fundamental law of nature a critical tool to be wielded against the unjust laws made by either tyrants or certain democrats (using Athenian history for his examples). Nevertheless, most of the laws he proposes are quite close to existing Roman institutions, reflecting a similar view to Scipio’s: that the Roman constitution is actually the best possible condition of a commonwealth. Defending the tribunate but criticizing secret ballots (he proposes instead that the people’s votes be open to the aristocracy to scrutinize), Marcus here demonstrates a reverence for the law as more than the sum of its parts. Particular laws may be changed or improved, but their reference point and justification should always relate to the cosmic reason that is embodied in natural law.

While natural law structures the cosmic order, private property comes about through a more tortuous route. Indeed, Cicero argues in another work, the De Officiis, that ‘by nature there is no private [property]’.36 Land becomes private as it is appropriated by groups of people in settlement, war, agreement or by lottery; so, too, individuals come into private property. Cicero concludes without further ado that ‘each man should hold on to whatever he has obtained’, and that to do otherwise is to violate ‘the law of human association’. This defines justice (respecting what is common as common and what is private as private).

When Cicero later returns to the topic of property, he criticizes a tribune who had, in 104 BCE, proposed an agrarian law tending to an equal distribution of material goods. In doing so, the philosopher adds a particular twist to the Stoic account of natural sociability: ‘Although nature has led men to congregate together, nevertheless they sought to live in cities in the hope of protecting their material things.’37 The life of the advanced political community is based on the motive of protecting private property, and this is a baseline requirement – though not perhaps the highest aspiration – for its justified existence. He goes on to attack those elite politicians (such as Julius Caesar) advocating land reform, known as populares for their policies favourable to the plebeians, for undermining the concord and equity that are the foundations of the political community.

By basing justice firmly on the rights of private property, Cicero advanced a tradition of Roman thought about justice and property that was unabashedly elitist in its context, in at least two ways. He worked to entrench certain entitlements of the political elite, and he rejected any redistribution of certain public lands. These political (and social and economic positions) underpinned his broader ethics of republican probity. As a result, those ethics were influential, though far from universal. In the rivalrous politics of his day, his understanding of justice and property was undeniably partisan. His ideas have, nonetheless, resonated beyond the confines of the debates of his own day.

Duties to Self, to Others and to the Commonwealth

Defending the nature and value of the commonwealth in abstract terms was one thing; determining one’s duty in defending it in practice, when its fundamental provisions for allocating and restraining power were threatened, was something else – though for Cicero the two were intimately related. We find him reflecting on these dilemmas especially in the De Officiis, his last philosophical work, written while he was also composing the series of speeches in which he risked his reflection on them at high stakes: the fourteen Philippics in which he attempted to muster opposition to Mark Antony. In the De Officiis he sought to prove that the duty or obligation (officium) that it was always honourable to perform (honestas) could never contradict one’s advantage or benefit (utilitas). In the Philippics, he pursued a course that he believed honourable, even though it posed the gravest threat to his life, relying on his view that one’s duty as a citizen is the highest and most honourable duty that one has. As he wrote in the Second Philippic (the only one not delivered as a speech at the time), ‘I will freely put my own body on the line, if by my death the liberty of the city may be made present’ (2.119).38

Written in the autumn of 44 BCE, De Officiis was addressed as a work of ethical instruction and exhortation to Cicero’s 21-year-old son, advising him on the duties of a virtuous Roman citizen and upright human being, at a moment when the future prospects for fulfilling those duties within the traditional republican constitution were in grave doubt.39 Nevertheless, he lays out a handbook to honourable political success in the hope that somehow the political world he is describing may not come to an end. He harks back to the mos maiorum, the customs and practices of the ancestral Romans, idealizing their instinctive adherence to the virtues and duties. Even in the case of ten Romans who were captured by Hannibal after Cannae and sent to Rome, bound by an oath that they would return if their mission were unsuccessful, but refused to return to captivity – still Cicero commends the Senate of that time for having stripped them of their citizenship privileges in punishment for having broken their oath (1.40).

The heart of the argument comes in setting out the Roman officia, or duties, that subtly reshape the Greek virtues. The Romans include wisdom and justice, as did the Greeks, but also greatness of spirit and decorum. These latter virtues had featured in Greek writing in various ways, but neither was ever as central in Greek ethics as Cicero makes them for the Roman elite, whom he enjoins to aim for a greatness of spirit that nevertheless disdains human affairs as minor in comparison with the universe (1.72) and to manifest seemly conformity with expected conduct, or decorum, even while striving for renown. His injunctions here are specific. You should not hurry about huffing and puffing; neither should you stroll too languidly (1.131). You should converse wittily (1.134), not build a house beyond your means (1.139), nor elevate learning and study above ordinary social interaction (1.157). All of these ethical duties can be called honestas (virtuous, with the connotation of honourable).

The question, then, is how what is honestas comports with what is utilitas, the seemingly useful or advantageous. In this way, Cicero tackles in his De Officiis the same challenge as had Plato in the central arc of his Republic: is it really to my advantage as an individual to be just? And he gives essentially the same answer: when properly understood, justice (or duty) and advantage can never conflict. An action like stealing ‘destroys the common life and fellowship of men’, as does violence (3.21, 3.26): in acting unnaturally, one violates one’s own nature, in line with the Stoic ideas of natural sociability and natural law that we met in Chapter 6. Treating others unjustly cannot be to anyone’s real advantage, because it breaches the natural ties of solidarity that bind all humans.40

This claim can have a political edge. Cicero does not hesitate to condemn some Roman actions. The Romans’ sacking of Corinth in 146 BCE was, he says, not truly advantageous, for ‘nothing cruel is in fact beneficial’ (3.46). But, whereas Plato had delved into psychology to make his case, focusing on the psychic misery and strife that injustice constitutes, Cicero makes his as a practising lawyer. He confronts specific cases of apparent conflict – many of which had become stock tropes in the Stoic literature and that of their critics – head on.

Does the seller of a house have the duty to disclose all details about its condition, if doing so might lower the price and so his profit? (Yes.) Should one resist temptation to profit at the margins in administering the estate of an orphan (a task that often fell to the lot of prominent Roman men)? (Yes: though Cicero himself divorced his wife to marry an orphan whose estate he was administering, doing so – so thought observers – to get hold of her money.41 Would a good man who has temporary advantage in the corn market tell his buyers that more corn from other sources is on the way – ‘[O]r would he keep silent and sell his own produce at as high a price as possible?’ (3.50). (No: this is concealment in the interests of profit, which will make one appear to be ‘crafty, roguish and sly’ – a reputation that cannot be beneficial to possess.) Here Cicero appeals to the recent innovation in Roman legal practice of formulae banning malicious fraud (3.60): such formulae are exactly the kind of resolution of a legal dispute that he wants to effect in his philosophical analysis. Must one resist all temptation to act unjustly, even if doing so seems necessary in the pursuit of political success and glory – even if one believes that one can best serve the republic by attaining those heights? (Emphatically, yes.)

This pattern of analysis was put to work in a cloaked analogy for the tyrannicide of Julius Caesar, which had occurred not even a year before. ‘What if a good man were to be able to rob of his clothes Phalaris, a cruel and monstrous tyrant, to prevent himself from dying of cold? Might he not do it?’ (3.29). Cicero’s answer is telling. On the one hand, simply trying to stay alive for your own benefit by robbing someone else is against the law of nature. But, on the other hand, if by staying alive you can benefit the political community and human fellowship, you should do so. Similarly, ‘if a man who has deposited money with you were to make war on your country’, you should not return the deposit: ‘for you would be acting contrary to the republic, which ought to be the dearest thing to you’ (3.95). And, even more bitingly, in the case of Phalaris and other tyrants, ‘there can be no fellowship between us and tyrants … and it is not contrary to nature to rob a man … whom it is honourable to kill’ (3.32). This coded justification for tyrannicide would be enormously influential with medieval philosophers, although Cicero’s injunctions to political leaders to demonstrate liberality and good faith in De Officiis would become specific targets in Machiavelli’s The Prince (1513).42

Nevertheless, apart from these extreme cases, the moral duties of universal human fellowship identified by Cicero are limited and largely negative. ‘One should not keep others from fresh water, should allow them to take fire from your fire, should give trustworthy counsel to someone who is seeking advice’ (1.52) – but one has no duty to be generous except insofar as this is compatible with one’s own light shining no less (in the poetic phrase he quotes, 1.51). This is because everyone has special duties of liberality to those close, and also duties of civil law to respect private property once established by law and custom of use. These closer ties arise first from the animal drive to procreate, producing marriage, children, and then family and the bonds of marriage that unite people by blood and by their religious duties to the ancestors. The Cosmopolitan ideas that Cicero entertains find their limits and, for the most part, their practical realization in the attitude one adopts towards one’s ties to more local communities.

While familial bonds are closer and more intimate, Cicero insists that ‘of all fellowships none is more serious, and none dearer, than that of each of us with the republic’ (1.57). Able men have the duty to serve it by engaging in public life and so therefore can achieve and display greatness of spirit (1.72). The Roman republic is the best possible constitution – the argument he had given to Scipio, now in his own voice; and the best human life, perfecting the sociability that animates humans to live together and the justice that they thereby seek to protect, is the life lived in such a regime in which power, deliberation and liberty are allied together.

Cicero had a particular vision of what that required. His hostility to land reform and insistence on deference to the Senate was not shared by all republicans of his time or before or since. In the kind of regime he praised (and even in the most radical populist thinking of his opponents), the Roman poor were accorded none of the powers of initiative or lottery selection, and fewer of the powers of accountability and control that had been exercised by their Athenian counterparts. The particulars of Cicero’s anti-populist stances, as well as his broader vision of popular liberty as secure only when balanced by more informed counsel and by decisive executive powers, have been recurrently adopted in later thought. Most profoundly absorbed by later ages was his model of a citizen’s duties, and his idea of how citizenship and a healthy constitution for the res publica mutually reinforce one another.