Bookwheel, from Agostino Ramelli’s Le diverse et artificiose machine, 1588.

THERE ARE TOOLS, such as the handsaw, that develop slowly and are refined over centuries. Others, such as the carpenter’s brace, are adaptations of a new scientific principle. Then there are those inventions that appear seemingly out of the blue. The button, for example, a useful device that secures clothing against cold drafts, was unknown for most of mankind’s history. The ancient Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans wore loose tunics, cloaks, and togas. Buttons were likewise absent in traditional dress throughout the Middle East, Africa, and South Asia. True, the climate in these places is mild, but northern dress was likewise buttonless. Eskimos and Vikings slipped their clothes over their heads and cinched them with belts and straps; Celts wrapped themselves in kilts; the Japanese used sashes to fasten their robes. The Romans did use buttons to ornament clothing, but the buttonhole eluded them. The ancient Chinese invented the toggle and loop, but never went on to the button and buttonhole, which are both simpler to make and more convenient to use. Then, suddenly, in the thirteenth century in northern Europe, the button appeared.1 Or, more precisely, the button and the buttonhole. The invention of this combination—so simple, yet so cunning—is a mystery. There was no scientific or technical breakthrough—buttons can easily be made from wood, horn, or bone; the buttonhole is merely a slit in the fabric. Yet the leap of imagination that this deceptively simple device required is impressive. Try to describe in words the odd flick-and-twist motion as you button and unbutton and you realize just how complicated it is. The other mystery of the button is the manner of its discovery. It is difficult to imagine the button evolving—it either exists or it doesn’t. We don’t know who invented the button and the buttonhole, but he—more likely she—was a genius.

Maybe the screwdriver, like the button, is a medieval invention. I examine a book of engravings and woodcuts by the sixteenth-century artist Albrecht Dürer. Dürer occasionally portrays tools. A woodcut of the Holy Family in Egypt has Joseph using an adze to hollow out a heavy plank. In a Crucifixion scene, a man turns a large auger to drill preparatory holes for the spikes while his mate wields a heavy hammer. The fullest depiction of tools is in the famous engraving Melancolia I. A winged female figure is surrounded by an assortment of woodworking tools: a pair of metal dividers, an open handsaw, iron pincers, a rule, a template, a claw hammer, and four wrought-iron nails. But no screwdriver. Melancolia I includes several magical and allegorical objects such as an alchemist’s crucible, a millstone, and an hourglass, and art historians assume that the tools in Melancolia I were likewise chosen for their symbolic meanings. The hammer and four nails, for example, probably refer to the Crucifixion. Maybe the screwdriver simply lacked metaphorical weight.

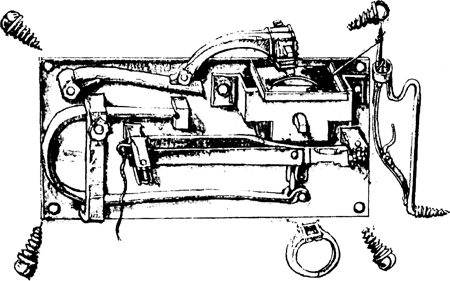

The most famous technological treatise of the sixteenth century was Agostino Ramelli’s Le diverse et artificiose machine (Various and ingenious machines), published in Paris in 1588. Ramelli was an Italian military engineer who had apprenticed with the Marquis of Marigano and moved to France to serve with the Catholic League in their war against the Huguenots. He had a colorful career. During the siege of La Rochelle he was wounded and captured, but escaped—or was exchanged—and a few months later successfully mined under a bastion and breached the fortification. His commander at La Rochelle was Henri d’Anjou, who became Henri III of France, and it was to the king that Ramelli dedicated his book. Capitano Ramelli, as he styled himself, was following in the footsteps of his celebrated countryman Leonardo da Vinci, and he was no less renowned; he is described by a French contemporary as “a true Daedalus as architect and the Archimedes of our age.”2 The frontispiece of Ramelli’s book shows a vigorous, bearded man holding a pair of dividers over a model of a fortification, his other, well-manicured hand resting on a steel cuirassier helmet. The author’s portrait is flanked by allegorical figures symbolizing his two vocations: war and mathematics.

Ramelli’s beautifully illustrated compilation of machines and technological devices was the most influential book of its kind. (Leonardo’s notebooks, while celebrated today, were not published until several centuries after the author’s death.) As is to be expected, the Capitano includes a number of siege engines, cunning pontoon bridges that unfold like accordions, scaling machines, and monstrous catapults. He also presents devices for clandestine break-ins: wrenches for tearing loose door bolts, giant clamps for forcing apart iron gratings and portcullises, and jacks for lifting doors off their hinges, “with great ease and little noise.” The latter claim, at least, is doubtful, since there is no provision for keeping the massive door, once free of the hinge, from crashing to the ground.

The majority of the two hundred machines in his book are peaceful devices. Ramelli was fascinated by the problem of raising water and included a variety of waterwheels, pumps, and bucket conveyor belts. There are also domestic gadgets such as automatic fountains and hand-cranked machines for milling flour. The latter is important since it is the first known example of the use of rollers, rather than millstones. Ramelli’s version of a revolving bookstand is particularly fascinating. Revolving bookstands were not unknown in Ramelli’s day and were used by scholars consulting several heavy tomes in turn. While a conventional bookstand turned horizontally and held four books, Ramelli’s six-foot-diameter bookwheel turned vertically, like a modern Ferris wheel, and could support no fewer than eight books. “This is a beautiful and ingenious machine, very useful and convenient for anyone who takes pleasure in study, especially those who are indisposed and tormented by gout,” he points out with no false modesty.3 The bookwheel was a mechanical tour de force. To ensure that the open books remained at a constant angle while the wheel turned, he incorporated a complicated epicyclic gearing arrangement, a device that had previously been used only in astronomical clocks. Of course, gravity would have done the job equally well (as it does in a Ferris wheel), but the gearing system allowed Ramelli to demonstrate his considerable skill as a mathematician.4

This splendid folly distracts me—I’m supposed to be looking for screwdrivers. As far as I can see, the heavy wooden bookwheel is held together with pegs. However, elsewhere in Ramelli’s book, I do find screws. The iron legs of the hand-cranked flour mill are attached to a wooden base with slotted screws, one of which is shown partially unscrewed to reveal the threads. This is proof that screws—and presumably screwdrivers—were used more than a hundred years earlier than any of my previous sources had suggested.

Another celebrated medieval technical book is De Re Metallica. This treatise on mining and metallurgy was written by Georg Bauer, a Saxon scholar whose Latinized pen name was Georgius Agricola. Agricola, Germany’s first mineralogist, laid the foundation for the systematic and scientific study of geology and mining. De Re Metallica, which appeared in 1556, shortly after his death, is heavily illustrated with woodcuts of mining and smelting machinery: pumps, mining hoists, and furnaces. Since many of the machines are made of wood, Agricola portrays a number of woodworking tools: axes and adzes for preparing heavy timber shoring; hammers and nails; mallets and chisels; and a long-handled auger for hollowing wooden logs into pipes.

He describes how to make the large bellows to be used for smelting iron. The woodcut illustrates the various components: the iron nozzle, the wooden boards, and the leather bellows. Ox hide is superior to horsehide, according to the author, who goes on to advise that “some people do not fix the hide to the bellows-boards and bows by iron nails, but by iron screws, screwed at the same time through strips laid over the hide.”5 I read the passage twice. Yes, he definitely says iron screws, and there, nestled in the bottom left-hand corner of the engraving, is a neat drawing of a screw. The tapered, threaded body is topped by a flat, slotted head. Although the means of driving the screw are not shown, Agricola provides clear evidence of the use of screws as early as the middle of the sixteenth century.

A technical work that predates both Agricola and Ramelli is the so-called Medieval Housebook. This handwritten manuscript, whose author and exact provenance are unknown, is thought to come from southern Germany. It has been described as a household manual for a knight’s castle, a common genre at the time.6 In its present state the book consists of sixty-three parchment leaves, beautifully illustrated and covering a variety of subjects: jousting, hunting, warfare, courtship. Astrological horoscopes describe traits of people born under the sign of different planets: the regal Sun, amorous Venus, warlike Mars. Industrious Mercury is accompanied by a variety of craftsmen: an organ builder; a goldsmith, wearing eyeglasses and hammering out a beaker; and a clockmaker. I examine the drawing through a magnifying glass, helpfully provided by the Frick Collection in New York City, where a traveling exhibition of selected pages from the Housebook is on display. I’m hoping to find a screwdriver on the clockmaker’s workbench, but no luck. The section on smelting includes a water-powered device for working bellows, but there is no indication that screws were used. Further on, several pages are devoted to the technology of war. I pore over each drawing in turn, under the watchful eye of an increasingly suspicious museum guard.

Among the intricate drawings of cannons, battle wagons, and scaling ladders, I find a collection of miscellaneous hardware: an auger, assorted manacles, and mysteriously shaped crowbars that the caption describes as tools for forcing apart iron gratings—ancestors of Ramelli’s portcullis twisters. Although the Housebook drawing shows a wrench, there is no screwdriver. But there is something almost as good. Two of the devices—a leg iron and a pair of manacles—are fastened with slotted screws.

The exact date of the Housebook is unknown. Most scholars believe that it was written between 1475 and 1490, almost a century earlier than the books of Agricola and Ramelli, and more than three hundred years before the Encyclopédie. Since the author of the Housebook included a separate drawing of a screw, one might guess that screws were a novelty. Interestingly, the screws in the Housebook are used to join metal, not wood. Such screws must mate with threaded holes, so these fifteenth-century screws were made with a relatively high degree of precision.

I have not found a screwdriver, but I have found a very old screw. Surely slotted screws were used for something less specialized than attaching leg irons and manacles? I go back to Dürer. Although his religious and allegorical engravings rarely include mechanical devices, an exception is his last etching, made in 1518. The subject is a cannon. It is being towed through a pastoral countryside, the roofs of a peaceful village visible in the valley below. The contrast between the artillery piece and the idyllic landscape is dramatic. This is also a comment on the mechanization of war, for the scene includes a glum-looking group of Oriental warriors holding swords and pikes. Dürer renders the cannon, its wooden carriage, and the two-wheeled limber in great detail. However, the iron parts of the cannon, including a complicated elevating mechanism, are not attached to the wooden frame with screws but with heavy spikes.

Dürer’s etching gives me an idea. Weapons have often been the source of technological invention. Radar and the jet engine, which both originated during the Second World War, are two modern examples. The most dramatic military innovation of the Renaissance was the gun. The first guns were bombards, short heavy mortars firing stone balls. Bombards were fixed to wooden platforms and were dragged from place to place only with great difficulty. Before the end of the fifteenth century, however, bell foundries cast bronze barrels, about eight feet long, that were light enough to be mounted on a wheeled carriage and were fully mobile. One of these innovative weapons is the subject of Dürer’s etching.

Before casting full-size cannons, foundries experimented with small portable weapons. The oldest surviving example of such a “hand-cannon” is a one-foot-long bronze gun barrel, made in Sweden in the mid-1300s.7 The barrel is attached to a straight wooden stock that the gunner either pressed against his body with his elbow or rested atop his shoulder like a modern antitank gun. Italians called the new weapon arcobugio (literally, a hollow crossbow). The Spaniards, who were leaders in gun-making, called it arcabuz, whence the French and English arquebus.

Firing an arquebus was tricky. After loading the gun by the muzzle, the gunner had to balance the heavy weapon with one hand while holding a smoldering match to the touchhole or firing pan with the other. Even when a forked rest or tripod was used, it was difficult to aim properly. In addition, bringing one’s hand close to the priming powder was dangerous since there was always the risk of a premature explosion. Groups of arquebusiers waving burning matches while pouring gunpowder on their priming pans were likely to cause as much damage to themselves as to the enemy.

A solution to the firing problem was developed in the early 1400s. A curved metal arm holding the match was attached to the stock. In the earliest versions, the gunner manually pivoted the arm, gradually moving the match to the touchhole. Eventually, the movement was accomplished by a spring-operated mechanism, the so-called matchlock. The arm holding the match was cocked back, and when a button was depressed, a spring brought it down to the pan. In a further refinement, pressure on a lever-shaped trigger—a feature adapted from the crossbow—slowly lowered the match into the pan. Now the gunner had both hands free to steady and aim the gun. The modern firearm had arrived—lock, stock, and barrel.

The arquebus quickly became popular. In 1471, the army of the duke of Burgundy counted 1,250 armored knights, 1,250 pikemen, 5,000 archers, and 1,250 arquebusiers.8 By 1527, in a French expeditionary force of eight hundred soldiers, more than half were arquebusiers.9 Gunners were common soldiers. Technological innovation often trickles down from the rich to the poor; firearms evolved in the opposite direction. The first arquebuses were disdained by the nobility as unwieldy, and too inaccurate for hunting. Only in the late 1500s did the gun become a gentleman’s weapon.

I go to the arms and armor gallery of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City to see these early firearms for myself. In a glass case I find a matchlock made in Italy in the 1570s. The gun is about three and a half feet long with an odd-shaped, curved wooden stock that resembles a field-hockey stick. This type of gun, known as a petronel, was developed by the French, who called it a poitrinal, since the stock was shaped to rest against the poitrine (chest). Petronels were short-lived—as a skeptical English soldier pointed out, “fewe or none could abide their recoyling”—and they were replaced by guns with so-called Spanish stocks, which rested against the shoulder.10

A musketeer firing his matchlock, 1607.

The petronel in the Metropolitan is elaborately ornamented and was obviously intended for hunting. The steel barrel and lock are engraved, and the stock is inlaid with carved bone. As I look closely at the decorations, my eye is drawn to the lock. The slotted heads of two screws are plainly visible. The lock is screwed—definitely screwed—to the stock.

Screws were probably used instead of nails to ensure that the lock was not loosened by the vibration of successive detonations. This use must have happened early, certainly before the 1570s. Since there are no older matchlocks in the Metropolitan, I consult a well-known reference book, Pollard’s History of Firearms. I find a detailed view of a matchlock in a drawing made in Nuremberg in 1505.11 The moving parts are fixed with rivets, but the mechanism itself is fastened to the stock with four screws, just like the petronel. In this exploded view the screws are shown in their entirety. They have round, slotted heads and threaded cores tapering to sharp points. The oldest depiction of a matchlock in Pollard’s is from a fifteenth-century German manuscript. The stubby weapon resembles a modern sawn-off shotgun. The short barrel sits in a wooden stock whose slightly angled butt suggests that the principle of transforming some of the shock of recoil into vertical movement was beginning to be understood. The precise drawing shows the right side of the gun. The lock is similarly attached to the stock with two slotted screws. The manuscript is dated 1475, about the same period as the Medieval Housebook.12 Here, at last, is a widespread application of early screws.

View of matchlock, 1505.

During the 1500s, the matchlock was replaced by a new type of lock—the so-called wheel lock. The wheel, which was on a spring, was wound up, or “spanned.” The key used to turn the wheel was called a spanner (which is what the English still call a wrench). When the trigger was pulled, the wheel turned rapidly against a piece of iron pyrites, producing a spark (the same principle as a modern cigarette lighter). The spark ignited the priming powder and the gun discharged. The piece of pyrites was held in a set of jaws that were tightened with small screws, and since it was necessary to regularly replace the worn pyrites, the gunner needed to have a screwdriver with him at all times. The solution was a combination tool: the end of the spanner handle was flattened to serve as a screwdriver. This must be the “arquebusier’s screwdriver” mentioned in Diderot’s Encyclopédie.

—

The matchlocks at the Metropolitan Museum are displayed in a small room that is part of a large area devoted to arms and armor. After examining the guns I decide to take a look at the armor. This is not research—I simply have fond boyhood memories of reading Ivanhoe and seeing the Knights of the Round Table at the movies. The centerpiece of the main gallery is a group of knights mounted on armored steeds. The armor, which was tinned to prevent rusting, is shiny. There are banners and colorful pennants, which give the display a jaunty, festive air; it is easy to forget that much of this is killing dress. The day I visit, the place is full of noisy, excited schoolchildren. I stop at a display case containing a utilitarian outfit, painted entirely black—not the Black Knight, just a cheap method of preventing rust. The beak-shaped helm has only a narrow slit for the eyes. “Neat!” the boy beside me exclaims to his companion. “It’s just like Darth Vader.”

The display is German armor from Dresden, dated between 1580 and 1590. This is slightly later than what is generally considered to have been the golden age of armor, which lasted from about 1450 to 1550. Contrary to the movies of my boyhood, King Arthur’s knights, who lived in the sixth century, would have worn chain mail, not steel armor. Protective steel plates came into use only at the end of the thirteenth century. First the knees and shins were covered, then the arms, and by about 1400, the entire body was encased. The common method of connecting the steel plates was with iron, brass, or copper rivets. When a small amount of movement was required between two plates, the rivet was set in a slot instead of a hole. Removable pieces of armor were fastened with cotter pins, turning catches, and pivot hooks; major pieces, such as the breastplate and backplate, were buckled together with leather straps.

The Dresden suit is identified as jousting armor. Jousting, or tilting, originated in martial tournaments in which groups of mounted knights fought with lance, sword, and mace. By the sixteenth century, this rude free-for-all had evolved into a highly regulated sport. Two knights, each carrying a twelve-foot-long blunted wooden lance, rode at each other on either side of a low wooden barricade called the tilt. The aim was to unseat the opponent, have him shatter his lance, or score points by hitting different parts of the body. To protect the wearer, jousting armor was heavily reinforced and weighed more than a hundred pounds (field armor was lighter, weighing between forty and sixty pounds).

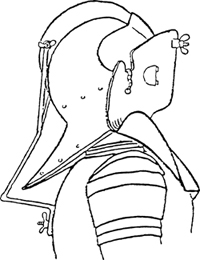

The black Dresden armor was for the scharfrennen, a particularly deadly German form of joust fought with sharpened lances and particularly popular with young men. Such combat required additional protection. The helm, called a rennhut, covered only the head and upper part of the face. The lower part of the face and the neck were protected by the renntartsche, a large molded plate that extended down to cover the left shoulder and was attached to the breastplate. A small shield, called a tilt targe, was fastened to the breastplate. Such “target” pieces were designed to fall off when struck; sometimes they were fitted with springs that caused them to fly dramatically into the air to the delight of the wildly applauding spectators.

Like most of the armor in the gallery, the steel plates of the Dresden suit are held together by rivets and buckled straps. Then I notice something: the renntartsche is screwed to the breastplate—the slotted heads, about half an inch in diameter, are plainly visible. Armorers, too, used screwdrivers! Since armor plate is relatively thin, these screws are probably mated with nuts, although I can’t see them since they are hidden inside the suit. The Greenwich Armory outside London employed a dozen or more general armorers as well as a variety of specialists such as platers, millmen, helmsmiths, mail-makers, and locksmiths. It was probably the latter who fabricated the screws (medieval locks sometimes used threaded turning mechanisms).

We can be fairly sure how these screws and nuts were fabricated. In Mechanick Exercises, Moxon includes a section titled “The Making of Screws and Nuts,” a process that could not have changed much since the Middle Ages. He describes how, after the head and shank are hammered out of a forged blank, the “screw-pin,” that is, the thread, is cut with a die called a screw plate. The screw plate, made of tempered steel, has several threaded holes of different diameters. The blank is placed in a vise, and the screw plate is forced down hard and turned to cut the threads. (The corresponding nut is threaded with a tap, a tapered screw fitted with a handle.) “Screw the Nut in the Vise directly flat, that the hole may stand upright, and put the Screw-tap upright in the hole; then if your Screw-tap have a handle, turn it by the handle hard round in the Hole, so will the Screw-tap work it self into the Hole, and make Grooves in it to fit the Threds [sic] of the Screw-pin.”13 Moxon’s complicated instructions underline the combination of delicacy and brute strength that was needed to make a screw in this fashion.

Looking more closely at the Dresden armor, I see that the helm is attached to the backplate by large wing nuts. Since the highest points in a joust were accorded to a hit to the helm, special precautions had to be taken to protect the head. Field helms were close-fitting and worn over a coif of chain mail; the heavy jousting helm, on the other hand, did not touch the head. It was supported on the shoulders like a modern deep-sea diver’s helmet and attached to the breastplate and backplate with leather straps to keep from getting knocked off. “In suits for the joust or tourney these adjustable fastenings could not always be depended upon,” observes Charles Ffoulkes in a 1912 book on armor, “and the great helm . . . [was] often screwed on to the suit.”14 Wing nuts, such as the ones on the Dresden armor, were a later refinement that allowed the exact angle of the helm to be closely adjusted. This was important. The so-called frog-mouth helm had a narrow, beaklike viewing slit, designed so that the knight could see out as he leaned forward in the saddle, riding toward his adversary. At the last minute, just before the moment of impact, he would straighten up and the lower part of the helm would protect his eyes from stray splinters. It required nerve: galloping down the list, aiming the heavy lance at one’s opponent who was barely visible through the helm’s shaking, narrow slot, then sudden darkness followed by the jarring crash of wood against steel.

Bracket for jousting helm and protective renntartsche, Dresden, sixteenth century.

Multipurpose armorer’s tool, sixteenth century.

It is unclear exactly when screws were substituted for straps. Ffoulkes refers to a French military manual, written in 1446, that provides a detailed description of jousting armor. The text refers to most attachments as cloué (literally “nailed,” as rivets were called arming nails), but in one place describes a piece as being rivez en dedens (fixed from the inside), which sounds like a screw and nut. I came across references to helms being screwed to breastplates as early as 1480.15 The oldest screw in the Metropolitan Museum is part of a steel breastplate that is identified as German or Austrian and dated 1480–90. If screws were used in the 1480s, that would make them the same age as the screws in the matchlock in Pollard’s History of Firearms and the metal screws in the Housebook. Ffoulkes describes the heads of the screws as square or polygonal. However, all the screws I saw at the Metropolitan were slotted.

I look through Ffoulkes’s chapter on “Tools, Appliances, Etc.” According to the author, few armorer’s tools have survived. He describes a display in the British Museum: “In the same case is a pair of armourer’s pincers, which resemble the multum in parvo tools of today, for they include hammer, wire-cutter, nail-drawer, and turnscrew.”16 He refers to a photograph. Excitedly, I turn to plate V.17 I had missed it earlier. Upon closer examination I can make out what looks like a pick at the end of one handle, and at the end of the other—a flat screwdriver blade. The caption beneath the photograph gives the date as the sixteenth century.

Another combination tool. I am disappointed that the oldest screwdriver resembles the kind of gimcrack household gadget that is sold by Hammacher Schlemmer. Although Ffoulkes calls this a turnscrew, like the screwdriver blade that was part of the arquebusier’s spanner, it probably didn’t have a special name. With so few screws, all that was needed was a part-time tool.