In 2006, Americans spent about $4 billion on bird seed and other food for wild birds and other animals. To put this in perspective, that same year they spent $7.1 billion on plasma TV sets, $11 billion on bottled water, $13.5 billion on home video and computer games, $24.1 billion on DVD rentals and purchases, and $58.5 billion on weddings. But that’s still a lot of bird seed!

People who spend their hard-earned dollars feeding birds want to ensure that they are helping, not hurting, them. And naturally we also want to provide food for the birds we most enjoy watching, like chickadees and cardinals. Many people consider squirrels and blackbirds to be nuisances. Some communities fine people if pigeons visit their feeders. Small wonder that I get hundreds of questions about bird feeding every year!

Q I love watching the birds that visit my feeders in winter, but I worry that the birds might become too dependent on me. Is it okay to keep feeding them?

A Yes. A study of 348 color-banded Black-capped Chickadees in Wisconsin found that the birds took only about 21 percent of their daily energy from feeders. The study concluded that although natural food supplied most of their needs, feeders provided an important supplement to their natural diet. The same researchers found that Black-capped Chickadees with access to feeders were more likely to survive very harsh winters. So your feeders can make tough times easier for the birds, but even when they visit feeders regularly, the birds still know how to find natural sources of food.

Q It seems like a bad idea to feed birds during spring, summer, and fall. Doesn’t it turn them into moochers and mess up their urge to migrate?

A Nope! The main cue that urges birds to migrate is the change in day length during spring and fall. Studies show that this instinct is so strong that when migratory birds are temporarily held in captivity with plenty of food, they become restless when it’s time to migrate. They even fly against the side of the cage facing the direction they must travel.

Migrating birds are typically in a hurry to reach their breeding grounds in spring or to travel to their wintering grounds in fall. Even if they find your feeder along the way, most birds typically won’t stop for more than a few days unless weather conditions are dire or they’ve lost a critical amount of weight and need to fatten up. During especially bad weather, feeders may mean the difference between life and death for some of these birds.

During spells of bad weather over the course of spring migration, when there may be little food available before the burst of plant growth and emerging insects, birds that seldom come to feeders, such as warblers and tanagers, may visit, particularly for suet. Keeping feeders active during spring and fall will attract local birds that are searching for the most reliable feeding areas, and their presence will entice migrants passing through your neighborhood to visit.

At times, a lost or injured bird may show up at your feeder, but remember that the injury or mix-up in the bird’s migratory instinct wasn’t caused by your feeders. Your feeders can buy some time for these individuals and give them a better chance to move on when they are ready.

Some people stop feeding birds throughout the summer months when other sources of food are more abundant. However, the nesting season demands a lot of energy from birds as they produce eggs and bring food (mostly insects) to their young. At these times, birds may welcome the opportunity to visit a feeder for a quick meal. I do close down my feeders if local birds start bringing their fledglings, because growing birds require a lot of protein and calcium, which birdseed and suet just don’t provide.

FEEDING AN ADDICTION (OURS!)

In addition to helping out the bird population, keeping bird feeders provides humans with enjoyment and satisfaction, affording us intimate glimpses of, and connections to, the natural world in our own backyards. Bird feeding often serves as a “gateway” activity that leads people into deeper experiences with nature, benefiting themselves and often leading them into active conservation activities that benefit the birds in return.

In addition to helping out the bird population, keeping bird feeders provides humans with enjoyment and satisfaction, affording us intimate glimpses of, and connections to, the natural world in our own backyards. Bird feeding often serves as a “gateway” activity that leads people into deeper experiences with nature, benefiting themselves and often leading them into active conservation activities that benefit the birds in return.

Q I’ve been feeding birds for decades, but now I find myself on a pretty rigid budget and can’t afford to spend so much. How can I keep feeding my chickadees and other favorite birds without going broke?

A Don’t economize by buying cheap mixtures: you’ll do more harm than good for the birds and won’t attract as diverse an assortment of species. Your best bet is to buy sunflower seeds and a couple of very small window feeders (which will exclude pigeons, jays, and all but the most brazen squirrels). Fill them with a small amount of food at the same time each day. During times when there are more birds than the food can accommodate, they’ll figure out alternative food sources, but your chickadees and their associates should quickly get into the habit of coming to feed at the same time each day.

In the long run, it’s most economical to buy quality seed in large quantities. If you do this when you’re feeding just a small amount each day, be sure to store your seed in a cool, dry place.

Q I set out my feeders a month ago and still haven’t seen a single bird! What’s wrong?

A It often takes a while for birds to discover a new feeding station, especially during the most severe periods of winter and the middle of summer. Local birds explore their area for new feeding opportunities during mild periods in winter. (That’s why the busiest feeders have far fewer birds on nice days than during bad weather.) Once a few local birds discover a feeder, they’ll draw the attention of others.

If you’re still having trouble attracting birds, you may need to make the area around your feeders more enticing to birds.

Q Where is the best place to put bird feeders?

A Place your bird feeders where you can enjoy the view, and where you can keep the birds safe. To minimize the chances that birds will collide with your windows, place feeders on poles or trees within three feet of a window. Feeders six feet or more from a window are the ones most often associated with fatal collisions.

Feeders affixed to windows don’t give birds enough distance to build up the kind of momentum that can kill or injure them if they do fly into the window. You can also place feeders directly on the window frame, or attach a window feeder to the glass with suction cups. As an extra measure of safety, select a location fairly close to trees or shrubs where birds can retreat when a predator approaches.

ATTRACTING BIRDS TO YOUR BACKYARD

ATTRACTING BIRDS TO YOUR BACKYARD

Even the most attractive feeding station is no more than a fast food restaurant for birds without the other necessities that will make them want to stick around. Native plants that provide food, cover, and nest sites are your best choices. Locally native plants are perfectly adapted for the soil and water conditions of your area and perfectly suited to the needs of native local wildlife as well. You’ll want an assortment of types, including nectar-producing flowering plants, fruit-producing shrubs and trees, and a variety of other trees for seeds, nuts, and nesting sites. Try to root out invasive weeds. Good sources of information about choices include local gardening and birding clubs, your county extension office, and your state or provincial department of natural resources.

A supply of clean water for drinking and bathing is also important. Many birds are attracted to birdbaths. Birds are especially drawn to the sound of dripping or flowing water, so setting up a plastic bottle with a small hole in the bottom above your birdbath to provide a slow, steady drip will bring in more individuals and more species than a birdbath alone.

Providing nest boxes and nest platforms will promote nesting. Fostering lichens and spiders will encourage tiny birds such as gnatcatchers and hummingbirds to nest nearby — they need bits of lichen and spider silk to construct their nests. You can also offer natural nesting materials such as cotton batting and short lengths of twine, placed in a clean suet cage or simply wedged into tree bark.

Q How do I attract orioles to my feeders?

A Orioles enjoy nectar and fruit. You can attract them with sugar water in hummingbird feeders, but make sure the perches are large enough for them. Some manufacturers make sugar water feeders specifically for orioles. Orioles can also be attracted to grape jelly, although never offer this in amounts larger than a teaspoon — it’s sticky! If you do offer jelly, it’s best in small containers such as jar lids.

Orioles also come to fruits. You can offer orange and apple halves on platform feeders or by skewering them on manufactured feeders or on nails pounded into a small board. You can also try setting out fresh grapes or berries, or raisins and currants (softened by soaking first), in a cereal bowl or other small container. Make sure to throw away or compost any fruits that get moldy.

Many people construct small backyard ponds to attract birds. These often attract insects, which will provide food for a broader selection of backyard birds. Make sure the water can’t become stagnant or it will be a breeding nursery for mosquitoes. Once the pond is established, if toads and frogs lay their eggs in it, the tadpoles will help keep mosquito larvae in check, as will any young dragonflies and damselflies during their nymph stage before they emerge as adults. These insects are doubly helpful because the adults feed on adult mosquitoes.

Many people construct small backyard ponds to attract birds. These often attract insects, which will provide food for a broader selection of backyard birds. Make sure the water can’t become stagnant or it will be a breeding nursery for mosquitoes. Once the pond is established, if toads and frogs lay their eggs in it, the tadpoles will help keep mosquito larvae in check, as will any young dragonflies and damselflies during their nymph stage before they emerge as adults. These insects are doubly helpful because the adults feed on adult mosquitoes.

Q I live in a high-rise apartment with a tiny balcony. Is there any way I can attract birds all the way up on the 17th floor?

A Depending on what the habitat below you is like, it may take some time for birds to discover your balcony. Bird feeders in high-rises along lakes and rivers are fairly likely to be discovered during migration. Feeders in any neighborhood are more likely to attract birds if there are trees and other vegetation at ground level, and the more plants on your balcony, the more likely curious birds will check it out. Providing food and nectar-producing plants may lure birds in, and will make your balcony more pleasant for you whether or not they ever arrive. You can learn more about attracting birds to city yards and balconies online at www.celebrateurbanbirds.org.

Q I love watching warblers and wish they would come to my feeders. Why don’t they?

A Warblers are insectivores, not seed eaters. Some people offer mealworms at bird feeders, but most warblers instinctively search for insects in specific areas within specific kinds of trees, rather than searching in a spot that might lead them to a feeder. The time warblers are most likely to discover a mealworm or suet feeder is during migration, especially during harsh weather. When they’re in an unfamiliar area, warblers often associate with chickadees, and a hungry warbler may notice the chickadees flitting back and forth from a feeder. After one warbler does discover a feeder, others may join it.

Pine Warblers and Yellow-rumped Warblers appear at suet feeders more often than most of their relatives, sometimes visiting a feeding station throughout a winter. Cape May Warblers, which drink nectar and feed on sap oozing out of holes drilled in trees by Yellow-bellied Sapsuckers, sometimes visit hummingbird feeders or an offering of sliced oranges.

Goldfinches are among the strictest vegetarians in the bird world, selecting an entirely vegetable diet and only inadvertently swallowing an occasional insect. Goldfinches even feed their nestlings regurgitated seeds, rather than the insects that most songbirds feed their young.

Q Someone told me that bird seed mixes aren’t good for birds — that I should be feeding them just sunflower seeds. But wouldn’t mixtures give a more balanced diet?

A According to results of the Seed Preference Test conducted by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, black-oil sunflower seeds attract the widest variety of species. Sunflower seeds have a high meat-to-shell ratio; they are high in fat (an important energy source for birds); and their small size and thin shell make them easy for small birds to handle and crack. (Striped sunflower seeds are larger and have thicker seed coats.)

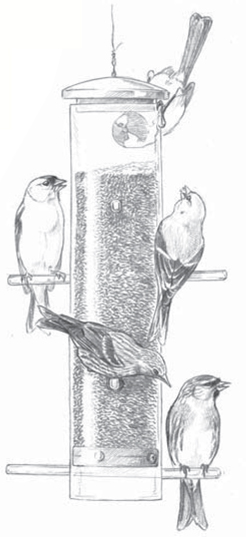

Most mixtures include less expensive “filler” seeds such as millet and milo, which are often left behind as birds eat the good stuff. When these and other seeds in a mixture are left uneaten, they can start molding and can contaminate fresh seed. The Seed Preference Test showed that millet is popular with sparrows, blackbirds, pigeons, and doves but ignored by other birds; milo is preferred only by jays, pigeons, and doves. Nyjer seed attracts goldfinches, redpolls, and siskins.

Q I was told that it is bad to feed birds in the spring when they are feeding their young because the adults will feed the babies the sunflower seeds from the feeders rather than the more varied diet they should be feeding them. Is this true? Do I have to give up my feeders in the spring?

A That all depends. If goldfinches or siskins are bringing sunflowers to the babies, it won’t hurt them — those nestlings or fledglings are pretty much vegetarians anyway. But once summer is underway, it might be bad to let cardinals, Rose-breasted Grosbeaks, or most other birds feed their babies too much sunflower seed or grape jelly, which don’t have enough protein for growing babies. As long as the families are only coming to the feeders once or twice a day, they should be getting plenty of other proper food.

Sadly, a few bird parents are as clueless as a few human parents are about their responsibilities. A 2009 study by researchers at Binghamton University showed that some urban crows overfeed their young junk food, preferring items that were easier to obtain over more nutritious fare. Fortunately, most birds innately feed their chicks a natural, protein-rich diet.

Summer feeders are especially helpful when incubating birds need a quick bite before they need to return to the nest, and when adult birds are spending every waking hour searching out insects for their babies. A bird feeder can give them some quick energy to keep doing what needs to be done for their babies.

Q I was trying to buy some thistle seed to attract goldfinches, and the woman in the bird-feed store said they didn’t sell it and wanted me to try something called “Nyjer seed.” What is that, and how is it different from thistle seed?

A Nyjer seed, also spelled niger seed, is a tiny black seed that resembles thistle, and it’s just as attractive to goldfinches, siskins, and redpolls. It can be fed in fabric tube feeders, called “thistle socks,” or in tube feeders with tiny openings. It is heat sterilized to prevent germination. If a few weeds with yellow flowers do sprout up under your feeder, pull them before they go to seed.

Q My goldfinches seem to love Nyjer seed, but after they’ve been feeding there is so much wasted seed on the ground! How can they possibly be getting any nutrition?

A What look like seeds on the ground beneath a feeder filled with Nyjer seed are mostly just the emptied-out outer shells. Finches slit open the outer coat and use their tongue to extract the tiny seed inside. Of course, the seeds are so tiny that when a finch pulls out one seed, a few others do spill on the ground. But finches usually arrive at feeders in flocks, and while some birds are sitting at the feeders, others are on the ground picking up the spilled seed.

Q How can suet be good for birds? Shouldn’t we be concerned about their cholesterol levels?

A Most birds thrive on a diet high in fats and proteins. Unadulterated animal fat is actually good for them, especially during cold weather. Unlike humans, birds metabolize fat very efficiently. This gives them the energy they need to maintain their body temperature.

Never offer suet when temperatures get warm enough to make it goopy — it may coat the feathers, making them harder to preen and less effective at insulating the bird. If the bird is nesting, some of the soft fat may be transferred to eggs, plugging the tiny pores that provide oxygen to the embryonic chicks. Also, warm raw suet grows rancid rather quickly.

If you feed suet when temperatures are above freezing, it should be rendered, that is, cooked so that the impurities can be strained off. Suet cakes sold in stores have been rendered and are usually okay for summer feeding during mild weather.

BANNING BACON

A great many birds love the taste of bacon fat. But like other processed meats, bacon contains nitrosamines, carcinogenic compounds formed from some of the preservatives used to cure the meat. Although nitrosamine levels in processed meats are far lower than they were in past decades, bacon does have detectable amounts of it. Compounding that, the very high cooking temperatures involved in frying bacon are conducive to nitrosamine formation. So despite the fact that birds love it, bacon and bacon fat pose too much of a risk to the long-term health of birds to warrant using it.

A great many birds love the taste of bacon fat. But like other processed meats, bacon contains nitrosamines, carcinogenic compounds formed from some of the preservatives used to cure the meat. Although nitrosamine levels in processed meats are far lower than they were in past decades, bacon does have detectable amounts of it. Compounding that, the very high cooking temperatures involved in frying bacon are conducive to nitrosamine formation. So despite the fact that birds love it, bacon and bacon fat pose too much of a risk to the long-term health of birds to warrant using it.

Q I bought some suet cakes that were recalled because they’d been tainted with salmonella. Is this a common problem?

A No, it’s not. Salmonella is unlikely to be a problem in rendered suet. In 2009, some suet cakes that contained peanut products were recalled because the peanuts had been contaminated during processing.

Peanuts and corn are exceptionally susceptible to contamination by bacteria and, especially, a fungus that produces extremely dangerous toxins, so those sold for human, pet, or livestock consumption are carefully screened. Screening is not required for products sold for wildlife consumption. For that reason, I prefer to buy suet cakes that don’t contain peanuts or corn, although they are usually safe, and conscientious manufacturers do recall them if a problem is discovered. Whether you’re feeding your birds pure, unadulterated fat or suet cakes made with other products, it’s best to stop offering it if birds aren’t finishing it quickly, especially in warm weather.

Red-tailed Hawks have been seen hunting as a pair, guarding opposite sides of the same tree to catch tree squirrels.

Q Is it okay to feed bread to birds?

A Bread gets moldy quickly, attracts rats and mice, and lacks the nutrients that most birds need. I strongly recommend other feeder offerings instead, especially sunflower seeds.

Ducks and pigeons can grow very fond of bread; it’s especially important to leave bread off the bird-feeding menu in cities that prohibit the feeding of these birds.

Q My neighbor puts out eggshells for birds to eat because she says it helps them get the calcium they need. Is that true?

A Yes. Especially during the nesting season, female birds require calcium to form strong eggshells. Birds can get calcium from natural foods, such as small snails, sow bugs, and slugs. But recent studies have found that in some areas acid rain leaches calcium out of the soil, possibly making it harder for these prey species to get enough calcium, ultimately affecting the birds.

You can provide a good source of calcium for the birds by crushing shells from hard-boiled eggs and setting them out for the birds to eat. If you use shells that haven’t been cooked, bake them in the oven at 250 degrees for 20 minutes to protect birds from salmonella. Don’t microwave them — they may shatter!

When birds are suffering from calcium deficiencies, they sometimes eat inappropriate substitutes. Blue Jays have been observed chipping and consuming house paint, especially in the Northeast when snow is covering the ground. Researchers believe the Blue Jays are interested in the calcium found in paint and that they are stockpiling the paint chips for spring. Unfortunately, paint also contains ingredients that might not be so healthy for the birds. Providing eggshells can help them while preserving your house!

WEDDING RICE — BAD FOR BIRDS?

Rice absorbs a lot of water when cooked, so some people worry that it might swell in birds’ stomachs, causing their stomachs to explode. But many birds eat uncooked rice in the wild. Bobolinks are even nicknamed ricebirds for this food preference. Even though rice thrown at weddings won’t result in exploded birds, some places ban throwing rice or birdseed at weddings for other reasons: slippery seed can be a hazard for wedding guests wearing smooth-soled dress shoes, and leftover seed or rice on the ground may attract mice.

Rice absorbs a lot of water when cooked, so some people worry that it might swell in birds’ stomachs, causing their stomachs to explode. But many birds eat uncooked rice in the wild. Bobolinks are even nicknamed ricebirds for this food preference. Even though rice thrown at weddings won’t result in exploded birds, some places ban throwing rice or birdseed at weddings for other reasons: slippery seed can be a hazard for wedding guests wearing smooth-soled dress shoes, and leftover seed or rice on the ground may attract mice.

Q Is it okay to feed peanuts to birds? Should they be salted or unsalted?

A You can feed birds unsalted peanuts, but beware of what you buy. Peanuts can harbor dangerous toxins produced by either of two harmful fungi, Aspergillus parasiticus or Aspergillus flavus. These aflatoxins can be lethal for humans and livestock, so peanuts sold for human consumption or for livestock feed must be screened for them. But there are no similar regulations regarding peanuts sold for feeding wild birds, so these dangerous poisons may be present in peanuts sold at bird-feed stores.

Peanuts sold in grocery stores have been screened. If you buy peanuts specifically sold as bird feed, make sure they’re clearly labeled as free of aflatoxins. Always store peanuts (for yourself as well as for birds) where they will stay completely dry, since moisture encourages fungal growth.

I would not use salted nuts. There are no indications that any birds prefer salted over unsalted, and the salt may be harmful.

Q Does peanut butter stick to birds’ mouths so they can’t eat, and they eventually starve?

A I know of no studies that support this, but it seems prudent, especially in warmer weather, to mix peanut butter with something gritty such as crushed eggshells or cornmeal.

If the weather is warm enough that peanut butter gets goopy, bring it in. Softened peanut butter can stick to belly feathers, reducing their waterproofing and insulation; and worse, if the bird is incubating eggs or brooding young, those sticky feathers may smear the oil onto eggs or baby birds.

Q What are mealworms and is it good to feed them to wild birds?

A Mealworms are larvae of a flightless beetle of the species Tenebrio molitor, and many birds love them. Mealworms are probably the single most inviting feeder offering for bluebirds, and if tanagers or warblers discover them, they may come right to your window to feed.

You can purchase mealworms in small quantities from bird-feed stores and bait shops, or in larger quantities from mail order distributors. Mealworms can be a pest insect in granaries, but in captivity they are easy to keep in small containers such as ice cream buckets or plastic tubs.

Feed the mealworms oatmeal and grains along with a few small pieces of potato, carrots, or apple as a water source. If mealworms arrive packaged in wadded newspaper, transfer them into buckets with proper food as soon as possible. They eat paper, and the toxic inks that may be present on the paper would be swallowed, which is probably bad for birds. In a cool basement, mealworms can be kept alive without reaching their adult stage for weeks. (Birds seem to prefer eating the larval-stage grubs to the pupae or adult beetles.)

Offer mealworms in small bowls or small acrylic bird feeders. (Tape any drainage holes closed to prevent the grubs from squeezing out.) Once birds discover them, you may be inundated. Your best strategy is to set out a small handful at one or more specific times of day. If you whistle every time you set them out, your chickadees may soon start flying in the moment they hear you.

Q Great Blue Herons, loons, eagles, and puffins all specialize on catching and eating fish, but they look so different! I thought things that caught and ate the same food evolved to look similar.

A All of these species do eat fish, but each has evolved a different way of capturing them and feeding them to their young. Herons stab or grab their fish from a standing position. Their bill and neck muscles are powerful and their feet are wide to support their bodies in wet mud without sinking. They catch most of their food in shallower water than do loons, which chase their fish through deeper water. Like herons, loons grab or stab a fish with their bills. In both cases, the feet and bill are well adapted for catching fish but are useless for carrying or tearing fish apart, so they swallow a fish whole.

Herons nest in trees, and their nestlings remain in the nest for several weeks after hatching. To feed them, herons first swallow the fish catch. With the weight in their stomachs, close to their center of gravity, they fly back to the nest to regurgitate the semidigested fish right into their nestlings’ mouths. Loon chicks follow their parents, who give them tiny fish and large aquatic insects until the babies learn to catch them on their own. They don’t need to transport fish anywhere.

When puffins spy a school of fish from the air, they dive into the water and start snapping up the little fish. They swallow some under water, or when the fish are abundant, may catch several to eat at the surface. Puffins nest in burrows. They feed their young whole little fish, which they carry back to land in their bills. The roofs of puffin mouths and their thick, muscular tongues have backward-facing spines that help them hold fish in their mouths even as they’re catching more.

When fish are abundant, puffins catch them close to their nesting sites, but because they may have to travel as much as 80 miles, or even more when fishing is poor, the adaptations that allow them to carry many fish at once help reduce the number of trips they must make to the nest. They can hold a dozen or more fish in their bills at one time. It’s a myth that they line up the fish with the heads facing alternate ways.

Bald Eagles and Osprey catch their fish with their feet, which are conveniently located near their center of gravity, so they can easily carry the entire fish back to their nests to feed their young. These raptors have sharp, hooked bills designed for tearing apart fish, so they eat, and then feed their young, chunks of fish rather than swallowing them whole.

Q Which birds especially like to eat bees?

A Bees are dangerous! Unless a bird knows instinctively how to safely catch and eat bees, either by selecting drones (which have no stingers) or by removing the stinger before swallowing its prey, it can be harmed or killed. I once witnessed a year-old captive American Crow catching a wasp in midair. The wasp stung its upper throat, and the bird died within minutes. Bees are loaded with nutrients and are fairly large, however, so it’s not surprising that some birds would have adapted to overcome their powerful defenses.

In North America, two birds are so good at catching bees that both are nicknamed the “bee bird.” One is the Eastern Kingbird. One study found that more than 32 percent of an Eastern Kingbird’s summer diet is composed of bees, ants, and wasps. Western Kingbirds also eat a great many bees.

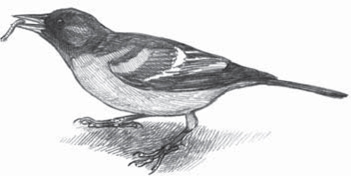

The other is the Summer Tanager, which is often found near apiaries. A Summer Tanager snaps bees in its bill (which is longer than most tanager bills, perhaps to hold these dangerous insects farther from its face) and carries the bee to a perch where it first slams it repeatedly against the perch to kill it and then removes the stinger by wiping the dead insect on the branch.

Beyond North America, one bird family, the bee-eaters (Meropidae, in the same order as our kingfishers), specializes on catching bees. Bee-eaters, found in Africa, southern Europe, southern Asia, Australia, and New Guinea, are beautifully colored birds. They catch bees in their long bill, and then, like our Summer Tanager, swallow the bee only after removing the stinger.

Q I often see flickers in my yard picking at the ground. Do they eat ticks?

A No, flickers specialize on ants. When a flicker finds an anthill, its long, sticky tongue traces the deep tunnels and pulls out lots of delicious ants. Of course, ants aren’t so delicious to most birds — their bodies contain formic acid (their family name, Formicidae, highlights this fact). In the 1800s, when many people bought birds at town markets to consume, some relished the spicy flavor of flickers while others abhorred it. John James Audubon, who tasted every bird he painted, wrote of the flicker, “I look upon the flesh as very disagreeable, it having a strong flavour of ants.”

American Goldfinches spend their entire winter eating sunflower and Nyjer seeds at feeders, and dried weed seeds in the wild. In spring, when the first dandelions go to seed, and as other natural food sources become available, goldfinches begin spending most of their time eating far from feeders. It’s very disappointing for those of us who watch feeder birds, because this usually happens right as the goldfinches are coming into their most gorgeous plumage.

American Goldfinches spend their entire winter eating sunflower and Nyjer seeds at feeders, and dried weed seeds in the wild. In spring, when the first dandelions go to seed, and as other natural food sources become available, goldfinches begin spending most of their time eating far from feeders. It’s very disappointing for those of us who watch feeder birds, because this usually happens right as the goldfinches are coming into their most gorgeous plumage.

Although goldfinches start pairing in April, they do not begin nesting until much later. Indeed, the American Goldfinch is one of the latest nesters in North America. In the East, goldfinches normally wait to begin nesting until late June or early July, when thistles, milkweed, and other plants with fibrous seeds have gone to seed. They use this downy material in nest construction, and the seeds themselves provide food for the chicks.

Q We’ve noticed that every year around mid-April, many of our backyard birds seem to disappear for about two weeks. Where do they go or what is happening?

A In April, many birds that spent the winter with us have migrated farther north. You won’t see them at your feeders again until late fall. At the same time, as natural foods, usually including insects, become more abundant, many year-round residents lose interest in feeders. Also, many resident birds gravitate to the areas where they’ll nest to feed, so they can spend more time courting and defending their territories.

Meanwhile, depending on weather, some birds that wintered in the southern states, such as White-throated Sparrows, haven’t yet arrived at their summer places, and Neotropical migrants are still even farther south. During the lull, we get a bit of time to savor robins, bluebirds, phoebes, and other early migrants before the floodgates of May open.

Q I’ve been a casual bird-watcher for many years but only recently started feeding them, and it’s opened a whole new world to me! It’s such fun going beyond just identifying them to observing their behavior. But now that I’m paying attention, I’m wondering why my chickadees come in flocks the way my goldfinches do, but the chickadees never sit side by side and eat together the way the finches do. Why is that?

A I agree that watching bird behavior is fascinating! Every species has its own set of behaviors that make it successful in its own habitat.

Goldfinches are one of the rare species that eat almost entirely seeds, even feeding their nestlings mostly a seed diet rather than the insects that most growing young songbirds need for protein. Goldfinches and their relatives tend to eat food items that are “patchy” — abundant in a few spots at a time while not at all available in other places. By spending time in a flock and wandering widely, they have plenty of opportunities to discover new patches of appropriate food. But these food supplies can be depleted within a short window of time, either as goldfinches or other animals eat them or as the plant sheds them. This is factored into the game plan of nomadic flocking birds: when the food is used up, they move on. So whether in the wild or at your feeders, normal goldfinch behavior is to feed together.

Chickadees aren’t nomadic — a winter flock stays within an area of about 25 acres (10 ha) for the entire season. Chickadee flocks benefit from many eyes to spot predators and new food resources, but individual birds hide and store seeds and other items for later feeding, so individuals prefer to keep more distance between themselves and other flock members. Usually chickadees space themselves from about 3 to 30 feet (1–10 m) apart, whereas the distance between goldfinches at a feeder can be measured in inches.

PUTTING YOUR OBSERVATIONS TO WORK

If you enjoy feeding birds, consider joining Project FeederWatch at www.feederwatch.org and contributing observations of all your feeder birds. Your sightings help scientists understand which changes at your feeders represent declines of birds across large areas, and which ones may reflect normal changes in the abundance of birds from one season to the next.

If you enjoy feeding birds, consider joining Project FeederWatch at www.feederwatch.org and contributing observations of all your feeder birds. Your sightings help scientists understand which changes at your feeders represent declines of birds across large areas, and which ones may reflect normal changes in the abundance of birds from one season to the next.

Q My grandmother in upstate New York has had bird feeders for as long as I can remember. The first Evening Grosbeaks I ever saw were swarming all over her feeder. Now she says that the grosbeaks hardly ever come to her feeders any more, and when they do, there are only a few. Are they becoming rarer than they used to be?

A Yes, unfortunately. The decline has been documented by participants in Project FeederWatch, which asks bird-watchers to count and report the number of birds they see at their feeders during winter. FeederWatch data gathered between 1988 and 2006 showed a 50 percent decline in the percentage of sites reporting Evening Grosbeaks. At locations where the grosbeaks were still being seen, average flock size had decreased by 27 percent. The cause is still unknown, but data from FeederWatch are bringing more attention to this worrisome decline and may eventually help us understand why it’s happening.

Q I went on a local field trip and the leader said chickadees eat a lot of insects in the winter. How is that possible?

A Because insects are cold-blooded, they may not be active in winter — but they’re out there! Many spend the winter months as eggs or pupae hidden in crevices in bark and twigs. Black-capped Chickadees are masters at locating them with their sharp eyes and at grabbing them with their tiny beaks, which can reach into crevices to pull them out. Chickadees also occasionally chip frozen fat or meat from carcasses. This shouldn’t be surprising considering they also feed on suet.

When someone offers mealworms, or a chickadee discovers an abundant source of insects, it may start storing, or caching its prey, but normally chickadees eat insects as they discover them in winter, caching seeds instead.

Although primarily insectivorous, the Black Phoebe occasionally catches fish. It dives into ponds to catch small minnows or other tiny fish and may even feed fish to its nestlings.

Q What’s the best thing to feed hummingbirds — honey or sugar? And should I use food coloring?

A Use a sugar solution, leave out the food coloring, and never use honey. Honey is more natural than processed sugar, and so some people assume it’s more nutritious. But honey fosters rapid bacterial and fungal growth. Always use regular processed sugar in your hummingbird feeders.

Hummingbirds are attracted to the color red, so some people add red food coloring to the sugar solution. Food coloring adds no nutritional value, however, and is harmful to hummingbirds. Attract the hummingbirds by choosing a feeder with bright red parts.

To make a sugar solution, mix 1/4 cup of sugar per cup of water, a good ratio especially during hot, dry conditions when hummingbirds may be somewhat dehydrated. During cold, wet periods you can strengthen the mixture, especially during spring and fall migrations, to 1/3 cup of sugar per cup of water. Boiling isn’t necessary if you use clean containers for measuring, use the sugar solution immediately, and change the solution every two or three days. If you mix up larger batches to be stored in the refrigerator, boiling is a good idea.

To make a sugar solution, mix 1/4 cup of sugar per cup of water, a good ratio especially during hot, dry conditions when hummingbirds may be somewhat dehydrated. During cold, wet periods you can strengthen the mixture, especially during spring and fall migrations, to 1/3 cup of sugar per cup of water. Boiling isn’t necessary if you use clean containers for measuring, use the sugar solution immediately, and change the solution every two or three days. If you mix up larger batches to be stored in the refrigerator, boiling is a good idea.

Q My hummingbird feeders keep attracting wasps and ants. What should I do?

A Ants can easily be controlled at suspended hummingbird feeders that are designed with a central moat at the bottom of the suspension wire rod. Fill the moat with plain water and ants won’t be able to reach the sugar water at all.

Unfortunately, there isn’t such a simple solution for discouraging bees and wasps. I’m not sure why so many feeders are equipped with yellow bee guards because bees and wasps are attracted to the color yellow, so the bee guards actually attract their attention. If solution drips from the feeder ports onto the guards, the bees get a tasty meal. I would never set out wasp traps or put anything toxic, such as insect repellents, on feeder ports — the risk of contaminating the food is too high.

I learned of one effective way of dealing with bees from an Oklahoma birder named Phil Floyd, whose wife figured out how to lure the wasps away from the hummingbird feeders without harming them. Phil wrote, “She filled another feeder with extra sugar content and also sprayed the outside of that feeder with the stronger sugar solution. She hung it in an area away from the other feeders. Then she went to the hummingbird feeders covered with bees, scraped several of them off into a jar, and took them to the new target feeder. She repeated this a couple of times until word among the bees spread and they all started going to the new feeder. We continued to keep the ‘bee feeder’ full of extra sugary water and kept spraying the outside with that same sugar solution. The bees took only to that one. Problem solved!” The heavy bee activity at the extra-sugary feeder discouraged hummingbirds from visiting that feeder.

Q I’ve heard that we should bring in our hummingbird feeders before Labor Day; otherwise hummingbirds might stay at the feeders instead of migrating. Is that true?

A No. Like other migratory birds, hummingbirds grow restless as day length decreases in fall, and not even the most wonderful feeding station can hold a hummingbird when the urge to migrate kicks in.

Stragglers aren’t stupid or lazy birds being enticed to remain by our feeders. Their bodies just weren’t quite fat and muscled enough to start the journey when the others departed. A few late Ruby-throated Hummingbirds are adult females whose first nest failed. It takes time for hummingbirds to recover after raising young, and our feeders can help them get enough calories to fatten up, which is especially important as flowers start drying up. Most late ruby-throats are juveniles that haven’t yet fully bulked up before they can leave. Our feeders can make the difference between life and death for some of these, especially after the first frosts.

Q The hummingbirds at my feeder seem to fight all the time. My feeder has eight ports — why can’t they share?

A Hummingbirds are aggressive for a good reason: they can’t afford to share flowers during times when not many blossoms are available. They may have to wander a long way after nectar is depleted. This aggression is so deeply ingrained that they just can’t figure out that the “nectar” in feeders virtually never runs out and doesn’t really need to be defended.

Overall, you’ll feed far more hummingbirds by setting out four tiny one-port feeders, spread out so a bird at one doesn’t easily see the others. You’ll get to watch hummingbirds through more windows, and they’ll be much happier, too.

RARE VISITORS: VAGRANT HUMMINGBIRDS

If you keep your hummingbird feeders up during the fall anywhere in the United States and southern Canada, you may get a surprise visitor. Hummingbirds from the tropics may suddenly appear, even as late as December. These poor birds are often doomed, but since our feeders are their only chance of survival, we can add days, weeks, or months to their lives. Some may even survive long-term, eventually heading back to more appropriate areas.

If you keep your hummingbird feeders up during the fall anywhere in the United States and southern Canada, you may get a surprise visitor. Hummingbirds from the tropics may suddenly appear, even as late as December. These poor birds are often doomed, but since our feeders are their only chance of survival, we can add days, weeks, or months to their lives. Some may even survive long-term, eventually heading back to more appropriate areas.

Rufous Hummingbirds breed in the northern Rocky Mountains and usually winter in Mexico and the Southwest. Some individuals winter in the southeastern states, and a handful even spend early winter in central and northeastern states.

Q My hummingbirds seem to be acting okay, but a yellowish powdery substance seems to be covering their faces and the base of their bills. I once read that hummers get a fungal disease when people feed them honey. Is this what’s happened to my birds?

A Honey does foster mold and bacteria growth, so don’t offer honey in a feeder. But from your description, your birds don’t sound ill at all — hummingbirds have such a high metabolic rate that when they get an infection, they get obviously sick and die pretty quickly. The yellowish powder on their faces and bills is probably pollen from the flowers they’ve been feeding on.

Mourning Doves usually feed on the ground, swallowing seeds and storing them in an enlargement of the esophagus called the “crop.” Once they’ve filled it (the record is 17,200 bluegrass seeds in a single crop!), they can fly to a safe perch to digest the meal.

Q So many grackles are pigging out at my feeders that the little birds can’t get in. What should I do?

A Grackles and most other blackbirds have bills that aren’t designed to crack open seeds with thick shells. Try offering striped sunflower seeds only, rather than seed mixtures or black oil sunflower seeds. Black oil sunflower is a little more nutritious but has a much thinner shell, easier for grackles and also House Sparrows to open. If you have a platform feeder, you can also try switching to a tube feeder, since grackles don’t usually visit hanging feeders.

Switching to striped sunflower seeds may also deter other birds that may be unwelcome feeder visitors, such as European Starlings and House Sparrows. These invasive species were brought to America from Europe. They nest in cavities but cannot excavate them themselves, so they take them from woodpeckers, bluebirds, and other vulnerable native species. It’s best to avoid subsidizing starlings and House Sparrows if you can.

Great-tailed Grackles are abundant and noisy, so they are generally considered nuisances in their range. But I will always have a soft spot for them. One morning when I was birding in Las Vegas with my first baby, I set him in his car seat on a picnic table in a city park while I scanned nearby trees. The Great-tailed Grackles were courting, which means they were making loud, bizarre whistles, rattles, and a variety of other cool noises. Joey giggled and cooed, happily engaged and entertained for more than 45 minutes while I looked at a variety of other birds I’d never have been able to enjoy but for those grackles.

Great-tailed Grackles are abundant and noisy, so they are generally considered nuisances in their range. But I will always have a soft spot for them. One morning when I was birding in Las Vegas with my first baby, I set him in his car seat on a picnic table in a city park while I scanned nearby trees. The Great-tailed Grackles were courting, which means they were making loud, bizarre whistles, rattles, and a variety of other cool noises. Joey giggled and cooed, happily engaged and entertained for more than 45 minutes while I looked at a variety of other birds I’d never have been able to enjoy but for those grackles.

Q My friend has a 40-foot pond with ducks in a rural setting in Arizona. She has a problem with a large population of grackles. Their noise and mess are driving her nuts. She wants to know what to do to get them to leave the area.

A Remember the line from the movie Field of Dreams, “If you build it, they will come”? In the case of Great-tailed Grackles in Arizona, if you provide water, they will come. These birds are so well adapted to urban, suburban, and rural areas with human habitation that once they colonize an area, they are very difficult to disperse. No matter what your friend does to discourage them, she may lose all her other birds before the grackles take the hint.

Tell her to make sure she’s not subsidizing them with food (all her feeders should be a type that excludes large birds), but if there are good supplies of natural food, she may simply be stuck. A simple solution if she happens to have a dog who chases birds and the time and patience to be vigilant for a few weeks: let the dog out to scare off the grackles whenever they make an appearance.

Q Can you name one good thing about pigeons?

A Pigeons came to America with early settlers, who brought them from Britain and Europe for food and sport. Pigeons have saved human lives by carrying critical messages during emergencies and wartime. One English hospital uses pigeons to transport blood samples to its laboratory across town, saving money and avoiding traffic jams.

Charles Darwin watched pigeons closely as well as raising his own, honing his theories by studying how different forms evolved due to selective breeding. Psychologist B.F. Skinner conducted many experiments on pigeons to study learning, and claimed that they were extremely intelligent animals.

At feeders, pigeons may be large and sometimes numerous, but they’re not particularly aggressive toward other birds. They don’t compete with native American birds for food or nest sites, and they do provide food for urban Peregrine Falcons.

Many people who feed birds wonder how to attract them without bringing in squirrels. Whole industries appear to have sprung up around creating the perfect way to foil squirrels, but often that tiny rodent brain seems more than a match for the average engineer.

My father-in-law designed an effective squirrel baffle using a large pizza pan. He cut a hole in the center, just a little larger in diameter than his feeder pole. He wrapped electrical tape around and around the pole where he wanted the baffle and then placed the pizza pan above the tape. Squirrels could not climb up the pole with the pan blocking the way, and couldn’t leap on the pan because it was so floppy they couldn’t get a footing. A cone of aluminum sheeting can also keep squirrels from climbing up the pole. Commercial baffles are also available.

But baffles work only if the feeder is too high and too far from trees for squirrels to leap to directly. If your feeder is anywhere within 8 feet (2.4 m) or so of a tree, a squirrel is eventually going to jump across and then teach its friends. Feeders on windows are also fair game. If there is a tree near your house, any self-respecting squirrel will quickly figure out how to leap to the roof and drop to the feeder from there. I’ve even seen large gray squirrels squeeze into my tiny acrylic window feeders.

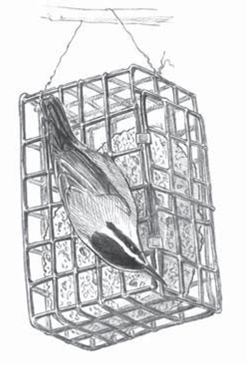

Another option is to purchase a feeder that has a cage around it, allowing small birds, but not squirrels, to get in and reach the seeds. These feeders may not be as aesthetically pleasing, but they will prevent squirrels from demolishing the seed supply. Of course, there is one more option — learn to enjoy squirrels and their antics.

A pigeonhole is a small, open compartment (as in a desk or cabinet) for keeping letters or documents; when we “pigeonhole” people or things, we place them in categories, usually failing to reflect their actual complexities. The term comes from the small nest compartments in pigeon coops.

Q It’s illegal to feed pigeons where I live. How can I keep them out of my bird feeders so I don’t have to pay a fine?

A If pigeons are coming regularly to your feeders, it may take some time and ingenuity to shoo them elsewhere. First and foremost, make sure seed doesn’t collect on the ground beneath your feeders. Also, pigeons are far more likely to come to platform feeders than any other kind, so you may want to close down those feeders and offer alternatives for the duration. Try a hanging feeder, since pigeons virtually never come to hanging feeders of any kind.

Q What’s the best way to clean a feeder?

A Hold it under running water in a laundry tub or with a hose in the yard while scrubbing with a brush. If you do this every few weeks and there is no evidence of illness in birds in your yard, you don’t need to do anything more.

Beyond keeping your feeders clean, it’s a good idea to rake up old seeds and shells beneath your feeders every few weeks, and more often during wet spells.

Q How often should I clean my birdbath?

A Clean your birdbath whenever it is visibly dirty, and at the very least every four or five days to prevent any mosquito eggs from hatching and the larvae from emerging. This is important not only because mosquitoes are pests to humans but also because they can spread disease, including West Nile virus. The best way to deal with algae without harming birds or our environment is to be proactive, scrubbing at the first sign of algae and rinsing thoroughly rather than resorting to detergents or bleach. Use clean water and a stiff scrub brush.

I’m sometimes asked about providing heated birdbaths in the winter. Generally, this isn’t a good idea. All animals require drinking water, and birds are no exception. They’re drawn to open water, and find birdbaths especially attractive when natural sources of open water are scarce.

I’m sometimes asked about providing heated birdbaths in the winter. Generally, this isn’t a good idea. All animals require drinking water, and birds are no exception. They’re drawn to open water, and find birdbaths especially attractive when natural sources of open water are scarce.

But when temperatures are well below freezing, open water steams up, and birds visiting it may become coated with ice. Worse, some birds may be tempted to bathe rather than simply drink, and when they hop out of the water, ice may form on their feathers, making flight impossible. I’ve heard firsthand accounts of this happening to European Starlings and to Mourning Doves.

I would never use a heated bath when temperatures were below about 20°F (–7°C) to prevent steam from coating feathers. If using a heated bath, it’s also a good idea to cover it with a grille of wooden dowels that allow birds to insert their beaks for drinking without being able to get their bodies into the water.

One thing to consider before buying a heated birdbath is whether it’s worth expending the natural resources to run the electricity. I often set a sturdy plastic bowl filled with water on my window platform feeder in the morning, and I bring it in when ice forms. Thirsty birds can get a drink, but since they can also get the water they need from snow and dripping icicles, I don’t feel that they’re deprived.

Q My neighbor says bird feeders are dangerous for birds because they foster the spread of diseases. Is this true?

A When birds are extremely concentrated, in either natural situations or at feeding stations, sick individuals can spread their germs to the other birds, so it’s prudent to close down your feeding station if you spot any sick birds. Wait several days after seeing the sick bird to replace the feeders, and thoroughly clean them and set out new seed when you do.

It’s also important to keep the ground beneath your feeders raked and clean of old, moldy seeds. When seeds collect on the ground beneath feeders and start to rot, birds may pick them up in their mouths. Bacteria growing on rotten seeds may spread to clean seed. Birds may get sick at one feeder and then spread their illnesses to other feeding stations through their droppings.

Although it’s possible for birds to become sick at feeders, I don’t want to overstate the potential harm. Our children may be exposed to dangerous germs at school, but overall the advantages far outweigh this small possibility, and we trust that conscientious parents will keep sick children home to minimize the danger. If there’s a risk of a serious epidemic, schools are closed. In the same way, the advantages of feeders usually outweigh the dangers as long as we’re proactive about cleanliness and quick to react when a sick bird does show up.

SEE ALSO: chapter 3 for more on dealing with sick birds.

Q Can bird feeders give people diseases?

A Public health departments don’t consider bird feeding a risk to humans. The vast majority of bird diseases don’t affect humans and the few that can, such as botulism and salmonella, are virtually never passed on to humans through contact with feeders. However, you should take a few easy and common-sense steps to ensure that bird feeders are safe for you and the birds.

Washing your hands after handling feeders and seeds is always prudent. You should also keep feeding stations clean and rake the area beneath feeders. Because the bacterium that causes botulism is found in soil regardless of the presence of bird feeders, it’s also prudent to wash hands after raking leaves or doing other yard work.

If you discover a sick bird in your yard or a bird that may have died of illness, close down your feeding station for at least a couple of weeks to prevent disease from spreading to other birds.

Q My landlord says he doesn’t want any bird feeders in our apartment complex. He claims that bird feeders attract pigeons, rats, and other vermin. Is this reasonable?

A Pigeons, rats, mice, and other animals that associate with humans are always searching for food resources, so if your feeders or spilled seed are accessible to them, they’ll come. Because rats and mice pose serious human health issues in urban areas and are difficult to control, it’s very important to be proactive.

Choose feeders on poles that rats and mice can’t climb, with wire mesh or weighted perches that exclude larger birds and squirrels. A seed catcher beneath to prevent seed from spilling on the ground is also a good idea. Keep your feeders meticulously clean, and clean up any spilled seed and hulls daily. Sometimes landlords are concerned about general sanitation, since rotting seed hulls building up near a building’s foundation can cause structural problems. If you can assure your landlord that you take his concerns seriously and are willing to do the work necessary to prevent problems, you may be able to change his mind.

Q I have wasps in my birdhouse. What should I do?

A Wasps and bees seldom usurp boxes from nesting birds. They are mostly found in empty boxes. If these insects are found in a box, it is best to let them be and not take any active measures to exterminate them. Instead, wait to clean them out in the fall when the weather is cooler and their activity has halted. You can prevent wasps and bees from establishing themselves by applying a thin layer of soap (use bar soap) onto the inside surface of the roof. This will create a slippery surface between the insects and the roof of the box. Never use insecticides in any nest box.