Acorn Woodpeckers store food in holes. These holes are often about the size you’d expect and, sure enough, often contain an incriminating acorn. Fortunately for all of us, they are far more likely to do this to trees than houses.

As wonderful as birds are, when the natural world collides with our own, sometimes it’s tricky figuring out how to solve the problems: Cardinals shadowboxing with their reflection on our windows. Woodpeckers carving up wood siding. Geese crowding onto the golf green. If I had a nickel for every time someone called my house asking me how to solve a bird-related problem, I’d be wealthy! Some issues are harder than others, but most of the time we can solve bird problems without harming birds. How? I’m glad you asked!

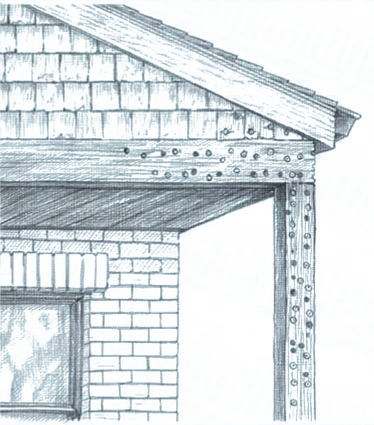

Q For the past few weeks, I’ve woken up to the sound of a woodpecker hammering on the house. I can see where it has been drilling holes under the eaves. I’ve tried chasing it away but it keeps coming back. Why does it keep eating my house?

A Woodpeckers don’t actually eat houses, though that is hardly a comforting technicality when they’re carving holes into your wood siding. They do eat insects in the wood, and they also chop holes into houses when trying to excavate cavities where they can nest, roost, or store their food. If you have the right type of house, they may also drum on it to defend their territories or to attract mates.

Woodpeckers declare their territory by hammering a specific rhythm on the most resonant structure they can find, often beginning early in the morning. Drumming can be loud and annoying, but it doesn’t cause serious damage — usually small dents in the wood, grouped in clusters along the corners or on fascia and trim boards. The holes may sometimes be as large as an inch across, round, cone-shaped, and generally shallow.

If the hammering isn’t particularly loud or rhythmic, the woodpeckers may be looking for food. Sometimes insects work their way into siding, especially grooved plywood siding. Leaf cutter and carpenter bees, grass bagworms, and other insects crawl into grooves in the siding; when woodpeckers hear them, they cut into the wood to get them. Holes made when hunting for insects tend to be small and clustered, usually three to six or so, often in a line.

Woodpeckers also sometimes dig holes in houses to make a place to roost or nest, usually on dark-stained or natural wood houses near wooded areas. These holes are usually dug in springtime and are large enough for the woodpecker to fit into.

Acorn Woodpeckers store food in holes. These holes are often about the size you’d expect and, sure enough, often contain an incriminating acorn. Fortunately for all of us, they are far more likely to do this to trees than houses.

A 2007 Cornell Lab of Ornithology study surveyed 1,400 homes in the area around Ithaca, New York, to learn which ones were most enticing to woodpeckers. It also tested six common long-term deterrents to see how effectively each prevented woodpecker damage.

The study affirmed that damage was most likely on homes infested with ants or carpenter bees. It also found that homes with vinyl or aluminum siding, or painted in light colors, were less likely to be attacked than houses with stained wood siding or siding painted a dark color.

If your house attracts woodpeckers, what do you do about it? The study tested deterrents intended to scare away the woodpeckers, such as life-sized plastic owls with paper wings, reflective streamers, plastic eyes strung on fishing line, and a broadcast system that played woodpecker distress calls and hawk calls. The study also provided alternatives for the woodpeckers, such as ready-made roost boxes and suet feeders. The only deterrent that worked consistently was the plastic streamers, but even they stopped the damage at only 50 percent of the houses.

At least half of the time, addressing woodpecker issues involves more than just trying to scare them away. The Cornell Lab has a great resource to help you identify what the woodpeckers are doing and then find an effective solution. Look for Woodpeckers: Damage, Prevention and Control at www.birds. cornell.edu/wp_about. Suggestions include using wood putty to fill nest and roost holes as soon as they appear and then discouraging woodpeckers from reappearing by covering the area with burlap for a few weeks. Burlap will also discourage drumming, since it dulls the sound.

The problem with insect-infested wood is more difficult, because woodpeckers will continue to come as long as your house harbors food for them. So you have to first get rid of the insects, then completely repair the holes with wood putty, in order to solve that problem.

Q For the last three winters, Blue Jays have been pecking at the south-facing front of our house, removing most of the paint by the end of the winter. Why do they do this, and is there any way we can get them to stop? They’re not only destructive, but it’s very annoying to have them hammering on the house every morning at daybreak!

A During the winter of 2000–2001, Deborah Jasak, a Project FeederWatch participant, called the Cornell Lab of Ornithology to report the same problem with Blue Jays taking paint chips from her New Hampshire house. When FeederWatch staff asked others if they’d had the same problem, they were surprised to hear just how widespread it is. After the Boston Globe ran a story about the issue, Massachusetts Audubon received 160 reports of Blue Jays chipping and eating paint from houses.

Why do they do it? Paint manufacturers use calcium carbonate, or limestone, as an extender pigment in paint, making paint a source of calcium. Another FeederWatch research project found that Blue Jays consumed more than twice as much calcium as other birds do. And they seem to take paint from houses mostly in the Northeast, where soils are unusually low in calcium. When Deborah Jasak put out eggshells, the jays started taking those instead and left her house alone. She tried other sources of calcium, such as oyster shells, sand, dirt, and trace minerals, but eggshells were the only effective deterrent, and if they got buried under snow, the jays returned to peeling paint off the house.

In rare cases, jays may take the eggshells yet continue to peel house paint. These intelligent, social birds develop habits that can be hard to break, and may simply enjoy the activity of paint peeling. You might try covering the painted area they’re damaging with screening or burlap, or hanging shiny helium balloons to float in that area. When I rehabbed birds, I learned that most birds, especially Blue Jays, seemed terrified of helium balloons and their unpredictable movements.

SUSPICIOUS THIEVES

Some Western Scrub-Jays search out their food items on their own, while others raid the food caches stored by other scrub-jays and also by Acorn Woodpeckers and Clark’s Nutcrackers. Researchers have found that when “thieving” scrub-jays hide their food items, they spend a lot of time looking around to check if other jays are watching them; nonthieving scrub-jays seem unsuspicious and don’t look around before hiding their own food. The more a scrub-jay engages in stealing food from others, the more suspicious it becomes.

Some Western Scrub-Jays search out their food items on their own, while others raid the food caches stored by other scrub-jays and also by Acorn Woodpeckers and Clark’s Nutcrackers. Researchers have found that when “thieving” scrub-jays hide their food items, they spend a lot of time looking around to check if other jays are watching them; nonthieving scrub-jays seem unsuspicious and don’t look around before hiding their own food. The more a scrub-jay engages in stealing food from others, the more suspicious it becomes.

Some animals seem to love it when scrub-jays raid them for food — if that food happens to be parasites. Western Scrub-Jays frequently stand on the backs of mule deer picking off and eating ticks. The deer seem to appreciate the help, often standing still and holding up their ears to give the jays access. If you’ve read Jack London stories, you may have noticed that he mentions “moose birds.” These are Gray Jays, which acquired that nickname because they sometimes pick the parasites off moose.

Q A cardinal keeps flying into my kitchen window. I think he’s doing it on purpose, and it’s driving me nuts. How can I make him stop?

A Many territorial birds are incensed when they discover another bird of their species and sex on their territory. Reflections in windows and auto mirrors can appear to be exactly this. Cardinals and robins are the species most likely to start attacking their window reflections, and the attackers are usually males. Sometimes female cardinals or robins will do this, and other species occasionally attack their reflections, too.

In nature, when a cardinal discovers another cardinal on his territory, he may first respond by making a warning call or fly to a perch and sing, or he may instantly lower his crest and make pee-too or chuck call notes. If the intruder doesn’t leave, he’ll lower his body, open his mouth, vibrate his wings, and make various other calls. If the other cardinal still doesn’t leave, he lunges, but usually the intruder escapes before it comes to blows. Wild cardinals often countersing with their neighbors, which may give an outlet for some territorial disputes without the birds resorting to physical battles. Wild cardinals have engaged in fighting and continual chases for as long as 30 minutes, but most physically aggressive encounters last only a few seconds.

Reflections don’t leave, however, and they don’t countersing. To drive the reflected bird away, the cardinal gets into full battle mode, lunging at the glass. But rather than flying away or engaging in a normal “chase,” the reflected bird matches every aggressive posture, and when the real cardinal hits, the window is unyielding. The real cardinal gets so intent on driving the reflection away that he may waste weeks fighting with it.

It’s not too hard to solve the problem if the cardinal is fixated on just one window. Just soap the outside of the window or cover it with screening or newspapers for a few days. Unfortunately, sometimes when a reflection disappears from one window, the cardinal searches for and finds it in other windows.

Sometimes you can scare a bird away by taping helium balloons or shiny streamers on the window. Their unpredictable movements may scare birds from approaching close enough to see their reflection. Usually by the time the helium is gone and the ballons sink, the bird will have moved on. Some people recommend using Great Horned Owl decoys to scare birds away, but I once saw a bird using one of those as a perch from which to more conveniently continue to attack the window.

MIRROR, MIRROR, ON THE WALL

Some birds, especially in the crow family, can probably recognize that a mirror reflection is just that, not a real bird. One experiment showed that magpies marked with bright yellow or red on the throat reacted to their mirror image by scratching at the colored area on their own body; birds marked with black matching their throat feathers didn’t react that way. This ability to recognize oneself in a mirror isn’t known to occur in other animals except primates, dolphins, and elephants. It’s unfortunate that cardinals and robins don’t share this ability!

Some birds, especially in the crow family, can probably recognize that a mirror reflection is just that, not a real bird. One experiment showed that magpies marked with bright yellow or red on the throat reacted to their mirror image by scratching at the colored area on their own body; birds marked with black matching their throat feathers didn’t react that way. This ability to recognize oneself in a mirror isn’t known to occur in other animals except primates, dolphins, and elephants. It’s unfortunate that cardinals and robins don’t share this ability!

No matter what you do, the cardinal won’t attack your windows forever; he’ll usually lose interest when the breeding season advances and passions aren’t running so high.

TURNING LEMONS INTO LEMONADE

Sometimes when people are faced with a bothersome situation, they turn it into a good thing. I had a friend who was dismayed when a Great Blue Heron started feeding in her pond, but she later decided that the beautiful heron enhanced her yard even more than the fish. Another friend invented complicated strategies for keeping squirrels out of his feeders, but none worked. He finally switched to devising feeders to challenge squirrels, rather than to exclude them. He got to know the individual squirrels in his yard, and now finds them as entertaining to watch as the birds.

Sometimes when people are faced with a bothersome situation, they turn it into a good thing. I had a friend who was dismayed when a Great Blue Heron started feeding in her pond, but she later decided that the beautiful heron enhanced her yard even more than the fish. Another friend invented complicated strategies for keeping squirrels out of his feeders, but none worked. He finally switched to devising feeders to challenge squirrels, rather than to exclude them. He got to know the individual squirrels in his yard, and now finds them as entertaining to watch as the birds.

When waxwings, robins, and other birds started devouring the fruit on my husband’s beloved cherry trees, he quickly noticed that the birds concentrated in the top branches. He decided that it was much easier to pick the lower branches anyway. No need to pull out the ladder anymore, he has company while he picks, and we still freeze enough cherries to last until the next year.

HOW TO PREVENT BIRDS FROM COLLIDING WITH WINDOWS

HOW TO PREVENT BIRDS FROM COLLIDING WITH WINDOWS

Of all the troubling issues facing birds in our backyards, windows are one of the most devastating. Current estimates are that every year, worldwide, billions of birds are killed in collisions with window glass. Some crash into lighted windows on tall buildings at nighttime during migration, but a great many collide with windows on our own houses. What can we do to reduce the kill?

There are two different strategies for protecting birds from glass: to make the glass more visible to avoid collisions in the first place, and to make collisions less lethal by placing screening in front of glass.

To make glass more visible, you can try window coverings that are opaque from the outside but provide a good view from the inside. Decals placed on the outer glass are also effective, as long as they’re placed very close together, separated by only 2–4 inches (5–10 cm). Streamers, sun-catchers, or other decorative objects only work if they, too, are placed close enough together and on the outside.

The problem with either of these is that if you set out enough of them to be effective, you can obstruct your own view. Some new decals appear almost clear to our eyes, but because they are visible in the ultraviolet range, birds can easily see them. Again, these must be closely spaced on the outside of the glass to be effective.

Lines drawn on windows with highlighter markers and “invisible markers” that glow under black lights are easily seen by birds and can stop bird collisions if drawn in a tight grid pattern with openings no wider than about 4 inches (10 cm) high and 2 inches (5 cm) wide. To take advantage of the ultraviolet properties of the markers, they need to be used on the outside of the glass, since glass filters out UV light. You must also redraw them frequently because UV inks fade noticeably in less than a week.

You can also make your windows more visible by setting your feeders on the glass or window frame. Birds feeding right there may notice the glass and avoid flying into it. If they do take off toward the glass, especially when an unexpected predator suddenly appears, their speed on takeoff is usually too slow to cause injury if they collide with the glass. It takes only a couple of wing beats before birds are going full speed, so feeders farther than about 6 feet (2 m) from windows are far more dangerous than those right by the window.

To make collisions less dangerous, netting or screening attached to the window frame must be taut and set a couple of inches in front of the glass, so the bird will bounce off before it reaches the glass. Window screen or garden netting can work. Make sure it’s taut enough to serve as a trampoline.

You can learn more about preventing window collisions from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology at www.birds.cornell.edu/Publications/Birdscope/Summer2008/window_screening.html.

Q A phoebe is trying to build a nest on my porch light. We use the light a lot at night, and last year when a phoebe nested there, the eggs never hatched. We suspect they got too hot because of the light, so we really want her to build somewhere else. What should we do?

A Your phoebe has decided, just as you have, that your neighborhood is the right place to raise children. And phoebes make a neighborhood a little better because they eat so many flying insects, including mosquitoes. But a nest on a front porch can certainly be inconvenient for us!

To discourage her from nesting on the light, you can wedge in an insulated work glove or something else that won’t be damaged or cause a fire if it gets hot. To expedite her choosing an alternative site, consider building a nest shelf somewhere else on your house. Plans for building one designed by the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources are available at www.learner.org/jnorth/images/graphics/n-r/robin_nestbox.gif. This plan is designed to serve robins, phoebes, and Barn Swallows.

Monitoring a nest can be fascinating for children, and you can have all the insect-eating benefits of a backyard phoebe without the porch-nesting drawbacks.

Q A mockingbird is singing right outside my window all night long. He doesn’t stop! Short of changing the front yard landscape, what do I need to do to shut him up, at least until sunrise?

A Mockingbirds who sing all night long tend to be young, still-unattached males or older males who have lost their mate, so the best way to quiet him is to entice a female mockingbird to your yard, too. He’s already doing his best to accomplish this, though to the disappointment of both of you, he’s not yet succeeded. The singing will end on its own, usually within a few days or weeks.

Strategies for dealing with the problem for the duration include shutting the sound out of your house, by either closing windows or using ear plugs, or sending him elsewhere. If you can pinpoint the tree he’s singing from, you might place nylon window screen fabric or a fabric with a similar weave atop the tree to discourage him from perching there. Using bird netting risks entangling him and other birds.

The situation brings to mind Robert Frost’s poem, “A Minor Bird”:

I have wished a bird would fly away,

And not sing by my house all day;

Have clapped my hands at him from the door

When it seemed as if I could bear no more.

The fault must partly have been in me.

The bird was not to blame for his key.

And of course there must be something wrong

In wanting to silence any song.

You might want to substitute for the final two lines:

But of course there must be something right

About getting a decent sleep at night.

The mockingbird was Thomas Jefferson’s favorite bird. He wrote a lot about its amazing mimicry abilities and songs, and how England had nothing to compare with it, in his Notes on the State of Virginia. He also had a pet mockingbird named Dick who lived in the White House.

Q If birds have eagle eyes, why do they crash into windows, power lines, and guy wires?

A Window glass is not only clear; it’s reflective. Sky and trees are mirrored in windows, and since there was no such thing as glass in the natural world for the millions of years that birds have been evolving, few wild birds have yet evolved any ability to notice it. Window glass may have been used in Italy nearly 3,000 years ago, but it wasn’t common in England until the seventeenth century. Huge picture windows have become widespread only in recent decades, much too recently for birds to have developed mechanisms to avoid them. Conservative estimates put the number of birds killed by glass every year in the United States from 100 million to as many as one billion.

Unlike branches and other natural structures, power lines and guy wires are straight and relatively thin, so they apparently appear two-dimensional, making it difficult for birds to gauge their distance from one until they’re crashing into it. There is little data in North America, but extrapolating from data in Europe, as many as 174 million birds may be killed in North America each year by high-tension line collisions. Nocturnal migrants are attracted to the vicinity of communications towers and their guy wires by the lights necessary to warn planes of their presence. Again little data are available, but the numbers of birds killed at communications towers and their guy wires is estimated to be from 5 million to 50 million every year.

In places where power line kills are known to be high, little, inexpensive objects called flight diverters can be placed on the lines, significantly reducing the kill. Some of these are as simple as wire coiled into a loose cone shape; others are more complicated, swiveling or rotating in 3 to 5 mph winds. They’re expensive to place on existing power lines but much less so to put on new lines as they’re being installed. Because they are three-dimensional and in some cases make noticeable movements, birds detect them and gauge their distance from them much better than they gauge their distance from wires without them. Encourage your local power company to use them on new wires.

BIRD ON A WIRE

Why is it birds can sit on electrical wires and not get zapped? To get zapped, they need to close the circuit so the current actually flows through their body. If you were standing on a metal ladder and touched a bird on a power line, you’d both get zapped, because the ladder touching the ground would close the circuit. A squirrel can safely run along a power line, but when it reaches the end, if it makes contact with the transformer while it’s still touching the wire, it will be electrocuted. When large birds perch on or very close to transformers and power lines, they often get electrocuted. As a matter of fact, in some areas electrocution is the main cause of mortality for Harris’s Hawks.

Why is it birds can sit on electrical wires and not get zapped? To get zapped, they need to close the circuit so the current actually flows through their body. If you were standing on a metal ladder and touched a bird on a power line, you’d both get zapped, because the ladder touching the ground would close the circuit. A squirrel can safely run along a power line, but when it reaches the end, if it makes contact with the transformer while it’s still touching the wire, it will be electrocuted. When large birds perch on or very close to transformers and power lines, they often get electrocuted. As a matter of fact, in some areas electrocution is the main cause of mortality for Harris’s Hawks.

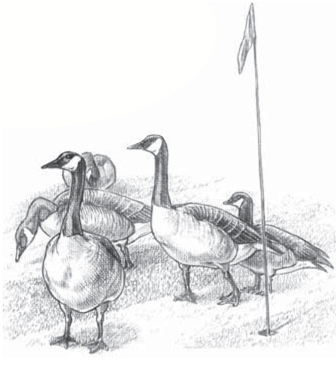

Q The geese on our local golf course are driving us crazy. They hiss whenever we come near, and I’ve slipped on goose poop and fallen on my keister twice! It seems like there are way more of them than there used to be. What can we do about them?

A Some Canada Geese are strongly migratory; they breed in northern Canada and Alaska and are seldom an issue in urban areas. But one subspecies of Canada Goose that isn’t highly migratory has indeed become a serious problem. Ironically, this subspecies, the “Giant” Canada Goose, was on the verge of extinction in the 1950s due to over-hunting and habitat loss. But in 1962 a small flock was discovered wintering in Rochester, Minnesota. Birds from this population were reintroduced to many towns and parks. At the same time, wildlife managers were introducing nonmigratory flocks of Canada Geese to many wildlife refuges throughout the northern tier of states. In most of these areas, no breeding population had existed before. Suddenly Canada Geese were flourishing.

Unfortunately, the ability of geese to digest grass, along with their preference for expansive lawns from which they can see predators approach, has drawn more and more of these human-acclimated “Giant” Canada Geese to urban areas, especially places like airports, golf courses, parks, campuses, and cemeteries. A manicured lawn by a river, stream, pond, or lake is an irresistible invitation to geese.

What’s the best way to deal with them? Allowing native vegetation to grow along shorelines and minimizing turf grass will at least reduce habitat for them. Obviously this isn’t possible at airports or golf courses. In those circumstances, one of the most effective methods of keeping geese at bay is to hire a herding dog and handler to regularly chase the geese off, especially in late winter and early spring to prevent nesting.

In smaller expanses such as individual small lawns, setting plastic netting atop the grass often works, though the netting can be expensive, and it has to be rolled up to mow; some people would rather deal with the geese.

Q Help! A heron is eating the koi in my pond! How can I discourage the bird and keep my fish safe?

A Great Blue Herons flock to koi or goldfish in ponds the way some people flock to sushi bars. They can’t help themselves! And once they’ve discovered a great fishing spot, it’s very tricky to get them to leave. Urban conservationist Rob Fergus writes, “Vigilance is required for homeowners who don’t want their koi pond treated as a giant bird feeder by herons. Since herons are fairly territorial, if one shows up uninvited (but face it, a bright orange fish is a pretty good invitation!), you may be able to drive it away with a life-sized heron decoy, available at many yard or garden centers.”

These decoys don’t always work. Rob warns, “Don’t leave the decoy out in the same place for too long, as herons will quickly learn that an unmoving bird isn’t a threat. It’s probably best to bring it out only when needed, and to move it to a new location at least once a day.”

Don’t bother with fake alligators floating in the water — they simply don’t work as anything but islands for turtles to rest on. Alternative solutions include setting netting above the pond or keeping a dog near the pond (assuming your dog doesn’t develop a taste for fresh-caught koi).

Q My cat Garfield never hurts birds, but my neighbor keeps asking me to keep him in the house. Why are bird lovers so paranoid about cats?

A The exact number of birds killed by cats each year is unknown, but the most conservative authoritative estimates place the annual kill in the United States at close to a hundred million birds every year, and some careful studies place the kill at about half a billion birds every year. Feral cats are a huge problem, but housecats that spend part of their lives outdoors also kill significant numbers.

Cats are “natural killers”; their instincts lead them to hunt small, moving creatures. But they are not natural in the sense that they’re not part of the animal life native to North America. They were brought here by humans and seldom survive to lead long and healthy lives unless they are subsidized by people offering them food and medical attention. When people do provide outdoor cats with medical treatment and care, or even just supplemental feeding, these felines can survive and even thrive, and may decimate local bird populations. They may be especially dangerous for migrating birds passing through unfamiliar areas. Outdoor and feral cats quickly figure out the patterns of when and where new migrants arrive, but these birds have no way of anticipating the presence of cats until it’s too late.

As a former rehabber, I have cared for hundreds of birds that had been attacked by cats. In all but one case, these birds have died from internal injuries or infections from the puncture bites. The only cat-injured bird I’ve ever restored to health required antibiotics for three full weeks.

In my lifetime I’ve taken in five stray cats. They all adapted well to indoor life. It’s harder to confine a cat that has spent its whole life going in and out but it’s not impossible. If you feel you must allow your cat to go outdoors, you can at least try to reduce the harm to birds by letting it out only at night.

Q I was thrilled when chickadees laid eggs in our nest box, but a predator got them before they hatched. How do I keep raccoons, cats, snakes, and other predators out of my birdhouses?

A A wide variety of commercial baffles and predator guards are available at bird specialty stores or on the Internet, or you can fashion your own. Some are designed to keep critters from climbing up the pole or tree, others to keep them from entering or reaching into the entrance hole. Unfortunately, some predator guards cause more problems than they solve, so be careful that your birds don’t have trouble getting in or feeding their young with these guards in place. Because predators vary locally, seek advice whenever possible from others in your community who have birdhouses and who may know about solutions that work in your area.

SOLVING THE FERAL CAT PROBLEM ONE CAT AT A TIME

My daughter Katie and her college roommate Stacey had a problem: a feral cat was eating birds in their Ohio backyard. The cat was young, beautiful, and hungry, but so were the birds she was eating.

My daughter Katie and her college roommate Stacey had a problem: a feral cat was eating birds in their Ohio backyard. The cat was young, beautiful, and hungry, but so were the birds she was eating.

When I visited, I witnessed the cat killing a beautiful Carolina Wren — an adult male who was helping his mate feed nestlings at the time. Without his help, the female wren would have to work much harder to raise their young successfully. The last straw was when I watched the cat stalking the mother wren.

But what to do? I headed to the grocery store and bought a can of cat food, using it to entice her into my car. I took an experimental drive around the block with the cat eating in the back seat. When we got back and I opened the car door, I expected her to make a run for it, but she continued washing her paws in satiated contentment in the back seat. So I drove 800 miles back to Minnesota with her.

“Kasey” was apparently so hungry for regular meals and a home to call her own that she was perfectly happy and well behaved in my car. She was infested with worms and lice, but after a few relatively small vet bills she became a healthy, happy indoor cat and my treasured companion.

Q Recently, I have been seeing cowbirds in my yard. I wish they would go away because I’ve heard that they lay their eggs in other birds’ nests. What can I do about it?

A It’s true that cowbirds lay their eggs in the nests of other birds that raise the hatchling cowbird, often at the expense of at least one or two of their own young. Cow-birds inhabit open grassland areas or areas near the edge of forests, and their range and their numbers in many areas have expanded as humans cut down forests for agriculture and development. In some wildlife refuges and other areas managed for critically endangered songbirds, cowbirds are legally trapped and humanely euthanized. But this isn’t permitted in most areas. Cowbirds are native American birds, covered by the same legal protections as robins and hummingbirds. It’s important to remember that cowbirds are fascinating birds in their own right and can only survive as nest parasites.

The most important thing you can do is to stop subsidizing them. Close down feeders that they visit or switch to foods they don’t like as much, such as striped sunflower or safflower seed. On a wider scale, encourage your local, county, and regional planners to limit the fragmentation of forests. We don’t have much power in most zoning and development situations, and even when our yards are covered with native vegetation rather than turf, roads and driveways create enough openings for cow-birds to feel welcome. So they’re an exceptionally frustrating problem. I wish I had a magic solution!

SEE ALSO: pages 151–155 for more about cowbird behavior.

Q I was excited to see a hawk in my yard a few weeks ago, until it started attacking the birds at my feeder. I even watched it eat one of my doves! What should I do?

A A few hawks, most often Cooper’s Hawks and, in areas of Canada and around the Great Lakes in the United States, Merlins (noisy, small falcons) have adapted to nesting in residential neighborhoods and have discovered that feeding stations are a reliable place to find easy prey. If you don’t want your backyard to be a regular hunting ground for them, it’s a good idea to close down your feeders for a few weeks so the raptors can develop a different routine. If they nest in your yard or a neighbor’s, you may want to keep your feeders closed for the summer and enjoy the opportunity to watch the nesting habits of these interesting raptors. But remember that hawks are birds, too. It’s hard for them to understand that a bird feeder isn’t a place for birds to feed on birds.

Q A Baltimore Oriole has taken over my hummingbird feeder and won’t let the little guys eat. What should I do to help my hummers?

A Like hummingbirds, many orioles feed on nectar. Orioles are considerably larger — a Baltimore Oriole is nine times heavier than a Ruby-throated Hummingbird, so if the oriole is the least bit territorial around the feeder, the hummers will hold back. But hummingbirds are probably the most aggressively territorial feeder birds, so even if your oriole were to leave, the hummingbirds would still fight over your feeder.

Probably the best solution would be to purchase a few more small hummingbird feeders to set in other areas of your yard. If you choose models without perches, the oriole won’t be able to use those, leaving them entirely to the hummingbirds. And by setting out two or three, your hummingbirds will be able to spend more time feeding and less time squabbling among themselves. You’ll be able to enjoy two of our most colorful, beautiful species!

Q A hummingbird got stuck in my neighbor’s garage and died before she could get it out. What should I do if this happens at my house?

A When birds panic, they tend to fly upward where, in their natural environment, they can escape every danger except aerial predators. So don’t chase any bird in the garage. Chances are high that it will stress the bird and cause it to stay up too high, where it can’t find the way out.

First, of course, open the door and windows, and cover with newspapers any windows that can’t be opened. Then try hanging something brilliant red — a hummingbird feeder is the best choice — right at the entrance.

Hummingbirds are often attracted into garages in the first place by the bright red door pulls suspended from many garage doors. If you have a recurring problem with hummingbirds flying in, try covering the door pull with black electrical tape.

Sometimes birds enter homes through windows or open doors. When a bird is trapped in the house, it’s best to try to confine it to a single room, closing all the doors. If you can completely open the windows in that room, sometimes the bird will fly out rather easily. It’s most effective if the windows have shades that can be drawn over the glass so the only visible part of the window is wide open to the outdoors. If you can’t open the windows, then close the drapes to darken the room as much as possible and, moving as quietly as you can, sneak up on the bird and toss a light towel over it. Then scoop it up, take it outside, and release it.

Q I found a pigeon with a band on its leg. It’s very tame and came right into the garage. What should I do?

A This bird is probably a homing pigeon. This breed belongs to the same species as common city pigeons (Rock Pigeons), but has been raised in captivity, so it trusts and depends on people. Like city pigeons, racing pigeons can be a variety of colors. Pure white homing pigeons are often raised for “dove releases,” to be let go at a wedding or other event. All of these homing pigeons usually find their way home directly.

But sometimes a homing pigeon gets lost or exhausted on a long journey, and rarely one gets injured. These birds often turn to strangers, as yours did, for food, water, and shelter.

Tracking down the bird’s owner can be a genuine kindness, both for the bird and the owner. Homing pigeons never wear the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service bands used on wild birds. You can locate the owner through the pigeon racing organization that produced the band, by looking for the letter code on the band. In North America, most bands have one of these codes: AU (American Racing Pigeon Union), CU (Canadian Racing Pigeon Union), IPB (Independent Pigeon Breeders), IF (International Federation of American Pigeon Fanciers), NBRC (National Birmingham Roller Club), or NPA (National Pigeon Association). These organizations’ websites will give you the information you need to find the owner.

Q What should I do if a bird crashes into my window?

A About half of the birds that initially survive a window collision end up dying from their injuries. They may be captured by predators while they are stunned, or succumb to broken wing bones, bruises, and serious internal injuries. But about half do survive.

If a bird gets knocked to the ground and lands upside down, it may lie there, unable to right itself for many minutes, and the entire time it’s on the ground it’s vulnerable to predators; so the best thing is to go outside and pick it up. That may be all the attention it needs — it may fly off instantly. If it pecks at you but can’t fly away, it is probably fairly seriously injured and should be brought to a wildlife rehabilitator immediately. If it is rather lethargic and can’t fly, it may have a minor concussion but may still be able to perch and balance. If that’s the case, place it in a nearby shrub and leave it to its own devices.

If the bird can’t balance or perch, place it in a shoebox lined with paper towels and bring it inside. You can help it stay upright by fashioning a donut cushion from tissues. In winter, keep a bird with extremely thick feathers in a basement or other fairly cool but not cold place rather than in a room that will feel excessively hot to it. Every 15 minutes or so, take the box outside and open it, to see if the bird flies off. Don’t open the box indoors! If the bird doesn’t recover within an hour or two, bring it to a rehabber. Never release any songbird at nighttime. It won’t be able to see well enough to find a safe roosting place.

SEE ALSO: pages 90–91 for information about preventing window collisions.

A HELPING HAND

To find a wildlife rehabber in your area, check the online directory at www.tc.umn.edu/~devo0028/contact.htm.

To find a wildlife rehabber in your area, check the online directory at www.tc.umn.edu/~devo0028/contact.htm.

Q We have a sparrow near our feeder that is just sitting still and not eating much. I’m afraid that it’s sick. What should we do?

A If a bird in your yard seems lethargic, is sitting still with puffed-out feathers, has crusted eyes, or shows other signs of illness, it’s best to immediately bring your feeders inside, clean and air-dry them thoroughly, and don’t begin feeding again for a week or so. This won’t help your sick bird, but it will send other birds away to reduce the chance of the disease spreading to them. If you have reason to believe that the bird was stunned by striking a window or was injured by a cat, then there’s no reason to close down your feeding station.

Don’t catch a possibly sick bird unless you already have discussed it with a wildlife rehabilitation clinic and have been told specifically that they will be able to take it. Many rehabbers are reluctant to take sick birds because they don’t want to put birds they’re already caring for at risk of communicable diseases. And unless you’re qualified and licensed, you may very well be letting yourself in for problems if you try to take care of it yourself. When birds are feeling sick or weak, they seldom preen, and lice and mites multiply quickly.

Q When I was taking a walk with a friend, we came upon an injured bird. We were both afraid to pick it up, so we just kept going. What should we have done?

A If a bird may be sick, it’s best to leave handling it to a wildlife rehabber. Depending on the disease possibilities, it may pose serious dangers to other birds at a rehab facility, and in some rare cases, the illness may even spread to humans, so interfering could cause worse problems.

If you can’t bear to leave a bird, or if it’s injured with little likelihood of making you sick (broken wings and cat bites are not contagious), you can help by transporting it to a wildlife rehabilitator. First put it in a cardboard box or a paper bag. Wear gloves if at all possible — strong leather gloves if the bird has talons (any hawk or owl) or has a sharp, potentially dangerous beak.

I keep a cardboard box lined with Astroturf on the bottom to provide footing (a few layers of soft paper towels can serve) in my car for this kind of emergency. I have a few numbers of local rehab centers written on the outside of the box so I can call the nearest one if I do find an injured bird.

The American Crow appears to be the biggest victim of West Nile virus, a disease introduced to North America in the 1990s. Virtually every crow who is infected dies within one week. No other North American bird is dying at the same rate from the disease, and the loss of crows in some areas has been severe. After the disease dies out in an area, crow numbers do seem to slowly recover.

Diseases that have been in the news in the past decade include a few that affected birds, too. West Nile virus, avian flu, and some salmonella outbreaks have raised everyone’s awareness and concern when they see a dead bird. Dead birds are sometimes of interest to health officials and scientists.

If you’re aware of a disease outbreak or are concerned about health issues, contact your local or county health department or the U.S. Geological Survey’s National Wildlife Health Center (www.nwhc.usgs.gov). Collect or dispose of the dead bird as they direct you. In many cases health departments will not be able to analyze a bird that has already started to decay, so you may be asked to double-bag it and put it in your freezer, or to take it to them immediately.

If you do pick up the bird be sure to wear disposable gloves or insert your hand into a plastic bag, pick up the bird with that hand, and then turn the bag inside out to contain the bird. Even if you’re pretty sure your skin didn’t touch the bird, wash your hands thoroughly afterward.

After any health and safety issues have been resolved, and especially if you know this bird was killed by a cat or in a collision with a window or automobile, or in some other way not associated with disease, you might turn your thoughts to collecting the bird for scientists at a university or museum. Start by contacting a wildlife professional who has a federal and state permit to collect birds or bird parts. (You may find such a person at a nearby university, museum, nature center, or an elementary or high school.)

The Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 protects native American birds, dead and alive, and their parts (feathers, eggs, and nests), by forbidding anyone without a permit to own or handle birds or bird parts. Though at first glance the law may seem overly strict, it serves an important conservation purpose by allowing authorities to curtail activities that harm birds. By having oral permission to salvage the dead bird, you’ll be able to show that you weren’t salvaging it to sell or possess.

If you’re instructed to bring the bird in under the authority of someone else’s permit, remember to record your name and contact information, the date and location, the bird’s species (if known), and a description of the circumstances, including your best guess about the cause of the bird’s death. Use a pencil or permanent ink. If you’re instructed to freeze the bird until you can bring it to the facility, double-bag it in plastic, and put the paper with this information between the two layers.

Q I noticed a House Finch at my feeder that looked like it was sick. When I looked with binoculars, I saw that one of its eyes was all swollen and gunked up. What was wrong with it?

A That bird was suffering from a nasty form of conjunctivitis called House Finch Eye Disease. The disease, caused by Mycoplasma gallisepticum, a common pathogen in domestic turkeys and chickens, had not been reported in songbirds until an outbreak in House Finches was first noticed during the winter of 1993–94 in Virginia and Maryland. The disease isn’t harmful to humans, but it can be fatal to House Finches. Volunteer bird-watchers joined the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s House Finch Disease Survey to help track the spread of the disease across the continent. Their reports helped scientists understand the dynamics of epidemics in birds. To prevent this sick bird from infecting other birds at your feeders, you should close down your feeding station for a couple of weeks. Thoroughly wash your feeders and let them air dry until you put them up again.

Q I was cleaning out my nest boxes and I found a dead adult Tree Swallow in one of them. How did it die?

A Tree Swallows migrate a long way — some of the birds that nest in northern Canada and Alaska winter down in Central America. If they arrive when the temperature is too cold for flying insects, their primary food, they may die of starvation or hypothermia. This is probably what happened to your swallow, especially if swallows or bluebirds have used your nest box successfully in past years.

There are a few other reasons why adult birds may die in a nest box.

If it had obvious injuries, especially on its head, it may have been killed by a House Sparrow trying to take over the box. In most cases, though, these competitors toss out birds after they kill them. Find ways to exclude House Sparrows from your nest boxes at www.sialis.org/hosp.htm.

If it had obvious injuries, especially on its head, it may have been killed by a House Sparrow trying to take over the box. In most cases, though, these competitors toss out birds after they kill them. Find ways to exclude House Sparrows from your nest boxes at www.sialis.org/hosp.htm.

Was the inside front of the box, below the hole, rough or grooved? Sometimes birds get stuck inside boxes because the inside walls are so smooth they can’t climb out. Tacking sandpaper or small strips of wood, making a sort of ladder, will prevent this in the future.

Was the inside front of the box, below the hole, rough or grooved? Sometimes birds get stuck inside boxes because the inside walls are so smooth they can’t climb out. Tacking sandpaper or small strips of wood, making a sort of ladder, will prevent this in the future.

Sometimes an infestation of blowflies or other parasites can become so intense that it kills not only nestlings but also adults. If there was no sign of young, that’s probably not the answer in this case.

Sometimes an infestation of blowflies or other parasites can become so intense that it kills not only nestlings but also adults. If there was no sign of young, that’s probably not the answer in this case.

Some wood preservatives may release harmful gases, especially in hot weather. Make sure any paints or varnishes that you use on your nest boxes are rated safe for indoor or playground use.

Some wood preservatives may release harmful gases, especially in hot weather. Make sure any paints or varnishes that you use on your nest boxes are rated safe for indoor or playground use.

Nestwatch, a citizen-science project of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, provides a wealth of information for people with nest boxes. NestWatch, a citizen-science project of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, provides a wealth of information for people with nest boxes. Consider reporting to NestWatch on the successes or failures of your nesting birds, to help scientists understand more about our breeding birds.

Q A robin missing an eye has turned up in our yard. He seems to be eating and acting normally. Should we help him?

A Many birds adapt to monocular vision and survive for years in the wild with one eye. When the eye is first injured, sometimes potentially dangerous infections set in. If the bird becomes lethargic and easy to catch, it probably is infected and should be captured and brought to a wildlife rehabilitator. (You can locate the nearest one to you at www.tc.umn.edu/~devo0028/contact.htm.) But as long as it’s acting normally and staying well out of reach, it’s doing fine and will be better off if left alone.

Q I saw a chickadee at my feeder with a bill so long and curved that it was having trouble eating. What was wrong with it?

A A large number of chickadees and other birds in Alaska have been developing unusual bills, often overgrown or crossed, in the past two decades. The outer sheath of the bill is made of a type of keratin, much like your fingernails, and in these birds this protective sheath is growing abnormally.

Colleen Handel, a biologist with the USGS Alaska Science Center, has documented bill deformities among 30 species in Alaska, from ravens and magpies to chickadees and nuthatches, and compiled records of at least 2,100 individual deformed chickadees in Alaska between 1991 and 2009 and 420 individuals of other species since 1986. She has been actively soliciting reports of deformed birds from outside Alaska but has received only 30 reports of deformed chickadees and 110 reports of other species from the rest of North America. Alaska has the largest concentration of bill deformities ever documented in the world.

Blood tests on birds with deformed bills found damaged DNA, consistent with environmental contamination or disease, though there have been no other obvious indications of disease. The reports cluster in late winter. Birds manufacture their own vitamin D, as we do, from exposure to sunlight, and vitamin D helps us absorb calcium. So chickadees visiting feeders, eating a higher proportion of seeds than they do on a natural winter diet of insect eggs and pupae, may be vulnerable to calcium deficiencies during the time of year when sunlight is lowest. This doesn’t explain the numbers of other, unrelated species that don’t visit feeders but still exhibit deformed bills.