CHAPTER 5

Actions Speak Louder in Birds: Bird Behavior

Birds are fascinating! Whether we’re watching cardinals nesting in a shrub near our window, a Red-winged Blackbird chasing a huge Red-tailed Hawk in the sky, or a pair of dancing Western Grebes scooting across a lake on our TV screen, we can’t help but marvel at the ways they go about their daily lives. Current research is establishing that birds are more intelligent than people once believed. Studies are also showing that birds such as chickadees and canaries replace brain neurons every year, allowing them to delete outdated memories and create new ones so their relatively small brain can keep up with their changing world. The more we learn, the more amazing birds prove to be.

How to Think Like a Bird

Q How big are bird brains?

A Bird brains are 6 to 11 times larger than those of similarly sized reptiles — comparable to mammalian brains as a percentage of body mass. Because bird brains are somewhat similar in structure to reptilian ones, scientists have long labeled the structures using the same terminology as for reptile brains. But in 2005, a consortium of neuroscientists proposed renaming bird brain structures to portray birds as more comparable to mammals in their cognitive ability. The scientists asserted that the century-old traditional nomenclature is outdated and does not reflect new studies that reveal the brainpower of birds.

Q I read in a newspaper column that hummingbirds remember the people who feed them. Is this possible?

A Alexander Skutch, who spent many decades studying birds in Costa Rica, wrote in his book The Life of the Hummingbird that after years of observation, he was convinced that they do remember. When a hummingbird comes to your window in spring and looks in as if expecting you to feed it, it’s easy to jump to the conclusion that the bird is the same one you fed the previous summer, and it probably is. But we can’t be absolutely certain about that without marking the bird in some way.

It’s harder to systematically study hummingbirds than larger species; only a handful of people are licensed to band hummingbirds, and the birds are so tiny that leg bands aren’t easy to read without recapturing the birds. Color-marking hummingbird feathers may affect how other birds respond to them, disrupting their normal social interactions and behaviors, and detailed research into the question hasn’t been done. So although my guess is yes, we can’t be scientifically certain.

CROWS NEVER FORGET EITHER

We know that American Crows remember human faces, thanks to a fascinating 2008 study. John M. Marzluff, a wildlife biologist at the University of Washington, noticed that birds he’d previously trapped seemed more wary of him and were harder to catch than crows that hadn’t been trapped by him before. So he devised an experiment to see if the crows really could recognize his face.

To test whether the birds recognized faces separately from clothing, gait, and other characteristics, Dr. Marzluff got some rubber caveman and Dick Cheney masks. Wearing the caveman mask, he and his team trapped and banded seven crows on the university’s campus in Seattle. In the months that followed, Dr. Marzluff and his students and volunteers walked prescribed routes around campus not bothering crows, but wearing either the caveman or the Dick Cheney mask. The crows scolded people in the “dangerous” caveman mask significantly more than they did before they were trapped, even when the mask was disguised with a hat or worn upside down. The Cheney mask provoked little reaction.

Over the following two years, even though no more crows were trapped or banded by people wearing the caveman mask, the effect actually multiplied. Wearing the caveman mask on one walk through campus, Dr. Marzluff was scolded by 47 of the 53 crows he encountered, many more than had experienced or witnessed the initial trapping. He hypothesizes that crows learn to recognize threatening humans from both experience and from their parents and others in their flock.

Then Dr. Marzluff repeated the experiment using more realistic masks made by a professional mask maker, trapping crows at various spots in Seattle while wearing one mask, the “dangerous” one. Afterward, he enlisted volunteers to walk through various areas of Seattle wearing either the dangerous mask or another style that the crows had not seen. The reaction to people wearing the dangerous mask was significant — crows scolded them, and in downtown Seattle even flew at them so close they almost touched them. The crows unerringly scolded the people wearing the dangerous mask rather than people wearing the mask that hadn’t been worn during trapping.

Young American Crows typically do not breed until they are four years or older. In most populations the young help their parents raise new broods for a few years. Families may include up to 15 individuals and contain young from five different years.

Q I seem to remember that when I was a kid, I saw a TV special with a man doing a dance with a Whooping Crane. Did that really happen or was it my imagination?

A You’re remembering a real bird and scientist whose wonderful interactions provided a lot of information about how to successfully rear some “imprinted” Whooping Cranes in captivity. Their bond actually led to a conservation triumph. The man was George Archibald, founder of the International Crane Foundation, and the Whooping Crane was Tex, a bird that had been hatched in the mid-1960s at the San Antonio Zoo and needed special care. Because she was hand-fed, she had imprinted on humans. Before she was old enough to breed, she was sent to the Patuxent Wildlife Center where they worked hard trying to get her to accept another Whooping Crane as a mate. But she clearly preferred her human handlers, never showed any interest in the other bird, and never laid an egg.

In 1975, Tex was moved to the International Crane Foundation in Wisconsin, under Archibald’s care, and the scientist began a long-term experiment to see if this imprinted bird would form a pair bond with a human so she could be induced to ovulate and be artificially inseminated. He moved in with Tex for several months in 1976 and established a pair bond with her, regularly dancing with her. He followed Tex’s lead and flapped and jumped. The next spring, she laid the first egg of her life, at age 10, but it was infertile.

They tried again the next spring and this time she produced a fertile egg, but the chick died just before hatching. In 1979, Tex’s egg was soft-shelled and broke. Finally, on May 3, 1981, Tex laid a fertile egg that hatched into a chick they named Gee Whiz. Tex was killed by raccoons in 1982, but her genes live on: Gee Whiz has fathered many crane chicks, some of which have been released into the wild in the Whooping Crane reintroduction project.

SEE ALSO: pages 141, 150, 213 and 235 for more on Whooping Cranes.

Parasitic Parenting and the Mysteries of Imprinting

Q Last summer I saw a Song Sparrow feeding its baby, only the chick was huge — it looked twice as big as its parent! How common is it for birds to produce such a gigantic baby?

A What you saw wasn’t a giant Song Sparrow — it was a Brown-headed Cowbird. The cowbird female laid her egg in the sparrow nest, and the pair of Song Sparrows raised it as their own chick. When young cowbirds start feeding on their own, they leave their foster parents and join a flock of cowbirds.

Cowbirds are brood parasites. They have no instinct to build a nest at all or to care for their babies directly. Rather, the females spend their spring and early summer searching out bird nests in which to lay their eggs. And cowbirds lay a lot of eggs — some may lay as many as 40 per season!

Cowbirds discover nests by sitting quietly, watching the comings and goings of other birds, and also by landing noisily in leaves while flapping their wings, which probably is done to startle and flush nearby birds off their nests. When they find a nest they wait until the brooding female is gone and then rush in. They usually eat or toss out one egg and lay their own. That parent sparrow is stuck raising the cowbird baby.

A Song Sparrow weighs 0.08 ounces (2.4 g) at hatching. It almost doubles its weight on the first day out of the egg, and by day 11, at the time of fledging, weighs two-thirds of an ounce (18.8 g). A cowbird isn’t much heavier when it first emerges from the egg, but within seven days weighs almost a full ounce (26 g). It begs more loudly and energetically, and its mouth is larger than the sparrow young, so it elicits more feedings than the sparrow nestlings. Unless food is abundant, the sparrow parents simply cannot provide enough food to meet the demands of the cowbird and all of their own young. Very often at least one of their own chicks will starve.

Q Why don’t birds just throw out the cowbird egg or hatchling instead of raising it?

A Most cowbird hosts are smaller than cowbirds, and their beaks are often too small to easily grasp a cowbird egg. In cases where they try, some of their own eggs may get scratched or punctured. A few birds have developed other strategies to get rid of cowbird eggs. When Blue-gray Gnatcatchers detect a cow-bird egg, they sometimes abandon their nest and start anew. Yellow Warblers sometimes build a new floor on their nest, relegating the cowbird egg, and any of their own eggs that were there, into the “cellar” where they won’t be incubated. Some Yellow Warbler nests have been found with as many as six layers, each with at least one cowbird egg!

But with these strategies, gnatcatchers and Yellow Warblers lose all the eggs they’ve already laid. Song Sparrows and most other hosts seldom gain anything if they toss out a cowbird egg in an attempt to protect their own young. Researchers have discovered that cowbirds periodically check nests. If a cowbird egg is suddenly missing, the adult cowbird often destroys the remaining eggs or chicks — researchers call this behavior “mafia retaliation.” So once a cowbird egg is in a nest, most birds have a better chance of successfully raising at least one of their own if they raise the cowbird.

Another reason that many birds raise cowbirds is that, overall, songbirds have an instinctive urge to incubate eggs and to feed young that they find in their nest. If they were suspicious of any egg or chick that didn’t look “right,” they might sometimes reject one of their own eggs or young. When most parent songbirds hear the sounds of a begging chick or see a chick’s colorful mouth opened wide, they instinctively search for food and try to feed it. In one experiment, European Pied Flycatchers continued to bring food to their own young even after the chicks were satiated when researchers played a recording of begging young. Wildlife rehabbers take advantage of this when they sometimes “foster” a baby bird out by placing it in a wild nest of the same species with young of the same age.

Although many bird behaviors, such as the urge to feed nestlings, are instinctive, these behaviors are refined by learning. The high cost of rearing a cowbird apparently leads some experienced birds to start figuring out that adult cowbirds present a problem. Researchers have found that older Song Sparrow females are more often heard making alarm calls when they detect a cowbird skulking near their nest than younger, inexperienced females do. Ironically, older Song Sparrows are also more likely than young ones to end up with a cowbird egg in their nest, probably because by making those alarm calls, they signal the cowbird that they’re nesting nearby.

Q If cowbirds are raised by other birds, why don’t they imprint on those species?

A People are still studying this issue. After cowbirds are independent, they join with other cowbirds and don’t associate with their foster parents any longer. Recent research suggests that female cowbirds may pay attention to their young. There are a handful of records of female cowbirds feeding cowbird nestlings or fledglings, including one record of a banded female feeding a banded chick that was identified as hers. There isn’t solid evidence that cowbirds regularly maintain contact with their young, though I’ve observed adult female cowbirds on the same branch as fledglings and there are many reports of adult female cowbirds feeding fledglings that may have been their own. Whether it’s learned or instinctive, cowbirds do apparently know that they’re cowbirds and not warblers, sparrows, or other species.

The colorful mouths of baby birds elicit feeding behaviors in the parents. In one case, a Northern Cardinal that lost his mate and young spent several days at the edge of a fish pond stuffing food into the colorful mouths of goldfish!

Cowbirds are the only parasitic birds in North America, but worldwide there are several more. Cuckoos, widowbirds, honey-guides, and Black-headed Ducks all must lay their eggs in the nests of other species and leave childcare up to them. Sometimes people use the word “cuckold” in reference to a man who is raising children who are not his own. This word comes straight from a reference to European cuckoos.

Learning about Food

Q Some birds eat all kinds of bugs and seeds, while others ignore what could be perfectly nutritious food and end up starving. How do birds recognize what is and isn’t food?

A Some birds are limited in their food choices by specialized adaptations in their bills, feet, ears, and eyes. A hungry Yellow-rumped Warbler may be able to feed on sunflower seed hearts at a feeder, but can’t crack open shells. Its digestive system, designed for digesting soft foods, can’t grind down the shell if it swallows the seed whole, so yellow-rumps ignore whole sunflower seeds. Unlike other warblers, yellow-rumps can digest bayberries and wax myrtle berries. Some bird bills are designed to extract food items from specific plants, and if birds don’t instinctively feed on the right plants, they’ll learn to or starve.

Hummingbird bills are an extreme example: their length and curvature can be so splendidly adapted to feeding in a specific flower type that they have difficulties getting food from other flowers. As a result, they have few competitors for the flowers they do use.

Shorebirds have bills specialized for taking different types of food at different depths in sand or mud. Ducks, spoonbills, and some other birds that feed on food items from the bottom of shallow open water have bills specialized to strain out the water, keeping the food items inside the mouth to swallow.

Osprey and Great Blue Herons feed on similarly sized fish but in different areas due to their specialized methods of catching them. When an Osprey catches a fish, it can carry it in its talons to the nest. Great Blue Herons have feet adapted for wading and for perching, not for carrying prey. They swallow the fish, fly to the nest, and regurgitate it to their young.

THE TASTE TEST

Birds that are specialized may be limited in food choices by their own bodies. But even generalists are limited in their food choices. Blue Jays are omnivorous, and during the course of their lifetime travels, they encounter many unfamiliar food items. Some berries and insects that seem perfectly fine may actually be toxic.

Birds that are specialized may be limited in food choices by their own bodies. But even generalists are limited in their food choices. Blue Jays are omnivorous, and during the course of their lifetime travels, they encounter many unfamiliar food items. Some berries and insects that seem perfectly fine may actually be toxic.

To test whether a novel item is edible or not, the Blue Jays I’ve observed in captivity take a fairly small taste and wait several minutes before eating more. If the item proves to be noxious, the jay will avoid similar items in the future; if not, the jay won’t delay in feeding on it the next time it’s offered. In one famous case, a captive jay ate a monarch butterfly that quickly made him vomit. After that, the jay always avoided orange butterflies even though other orange species aren’t toxic.

Great Gray Owls normally feed on small mammels, especially meadow voles, which they can hear when the voles are deep in their tunnels, even when those tunnels are buried under 18 inches (46 cm) of snow. The owls’ big ears, large but not very strong talons, and huge wings, which can push this fairly lightweight owl out of deep snow, are adaptations for catching their small, hidden prey. When vole populations crash, the owls may “invade” new areas en masse. Some will continue to feed almost exclusively on voles, but a few will learn to take other species. During the winter of 2004–05, hundreds of Great Gray Owls descended on northern Minnesota; some individuals were documented feeding on rabbits, squirrels, and even muskrats, but the majority stayed in grassy areas searching for voles.

Q How can Bald Eagles survive in northern areas after all the lakes have frozen?

A As much as eagles enjoy fresh fish, they will also dine on carrion and garbage. It may be disconcerting to see the emblem of the United States of America eating at a dump, but the ability of eagles to exploit a wide range of food choices is what makes them so successful.

Crows steal food from other animals. They have been observed distracting a river otter to steal its fish and following Common Mergansers to catch the minnows the ducks were chasing into shallow water. They sometimes follow small songbirds as they arrive from a long migration flight and capture and eat the exhausted birds. They may follow songbirds to their nests to find eggs and young birds. Crows also catch fish on their own, eat from outdoor dog dishes, and take fruit from trees.

EATING ON THE WING

The Common Nighthawk is specialized for taking insects in flight. It has an extremely small beak that is loosely attached to its huge, soft mouth. It opens its mouth wide and flies at moths and other flying insects, which go straight down the throat and esophagus without the bird stopping to swallow. But when the bird is on the ground, the most succulent bug could walk right past without being eaten: the bill is too small and frail, and the vestigial tongue too far back, for even the hungriest nighthawk to pick it up.

The Common Nighthawk is specialized for taking insects in flight. It has an extremely small beak that is loosely attached to its huge, soft mouth. It opens its mouth wide and flies at moths and other flying insects, which go straight down the throat and esophagus without the bird stopping to swallow. But when the bird is on the ground, the most succulent bug could walk right past without being eaten: the bill is too small and frail, and the vestigial tongue too far back, for even the hungriest nighthawk to pick it up.

When I was a licensed wildlife rehabilitator, I specialized in nighthawk care. To feed these birds when they first came to me, I’d have to very gently tease open the mouth, place mealworms or a special food mash in the back of the mouth, and stroke the throat to help get it down. After a few days, birds would run up to me with their mouths wide open to be fed, but they usually needed several days more to be able to swallow items without help. The wonderful adaptations that allow them to so successfully catch insects on the wing, limit their abilities to eat anything else.

WHO ARE YOU CALLING A BIRDBRAIN?

Here are some examples of ways in which birds are smarter than many people think.

In the wild, jays and crows can recollect when, where, and what food they’ve stored.

In the wild, jays and crows can recollect when, where, and what food they’ve stored.

Several species of birds, including nuthatches, have been observed using tools. Brown-headed Nuthatches in the Southeast have been documented using pieces of pine bark to pry off other flakes of bark, to reveal insects beneath. Pygmy Nuthatches in the West have been documented using a twig to probe crevices of a pine in search of insects.

Several species of birds, including nuthatches, have been observed using tools. Brown-headed Nuthatches in the Southeast have been documented using pieces of pine bark to pry off other flakes of bark, to reveal insects beneath. Pygmy Nuthatches in the West have been documented using a twig to probe crevices of a pine in search of insects.

At least one species, the New Caledonian Crow, actually makes tools. One fascinating captive individual named Betty can fashion a hook out of a piece of wire to reach and pull food out of a tube. In the wild, these birds hold pointed sticks or needles in their beaks to extract insects from logs.

At least one species, the New Caledonian Crow, actually makes tools. One fascinating captive individual named Betty can fashion a hook out of a piece of wire to reach and pull food out of a tube. In the wild, these birds hold pointed sticks or needles in their beaks to extract insects from logs.

Some herons catch fish by setting out bait for them. One popular YouTube video shows a Green Heron dropping bread in the water and moving it about while waiting for fish to nibble at it.

Some herons catch fish by setting out bait for them. One popular YouTube video shows a Green Heron dropping bread in the water and moving it about while waiting for fish to nibble at it.

Crows in urban Japan drop hard-shelled nuts onto intersections; they wait for them to be cracked open by cars, and then retrieve them while the cars are stopped after the light turns red.

Crows in urban Japan drop hard-shelled nuts onto intersections; they wait for them to be cracked open by cars, and then retrieve them while the cars are stopped after the light turns red.

A few species in the crow family have been documented dropping whelks (large marine snails) and other shelled animals from the air onto rocks and other hard surfaces; the drop breaks the shell and then the crow flies in for a meal.

A few species in the crow family have been documented dropping whelks (large marine snails) and other shelled animals from the air onto rocks and other hard surfaces; the drop breaks the shell and then the crow flies in for a meal.

Western Scrub-Jays can attribute their own motives to other scrub-jays — those jays that take food from other jays’ food stores are more likely to keep moving and hiding their own food stores to prevent stealing than are “honest” jays.

Western Scrub-Jays can attribute their own motives to other scrub-jays — those jays that take food from other jays’ food stores are more likely to keep moving and hiding their own food stores to prevent stealing than are “honest” jays.

Researcher Irene Pepperberg’s African Gray Parrot, Alex, could identify by word fifty different objects, could recognize quantities up to six, could distinguish seven colors and five shapes, and understood the concepts of bigger, smaller, same, and different.

Researcher Irene Pepperberg’s African Gray Parrot, Alex, could identify by word fifty different objects, could recognize quantities up to six, could distinguish seven colors and five shapes, and understood the concepts of bigger, smaller, same, and different.

Many pet birds, including parrots, mynahs, and magpies, have learned to imitate human speech. Many owners have long insisted that their birds use words in the proper context. Although authorities have typically pooh-poohed this, Alex’s well-documented ability to use language is making many scientists take a second look at human language use in other species.

Many pet birds, including parrots, mynahs, and magpies, have learned to imitate human speech. Many owners have long insisted that their birds use words in the proper context. Although authorities have typically pooh-poohed this, Alex’s well-documented ability to use language is making many scientists take a second look at human language use in other species.

Birds Do the Strangest Things

Q I saw the funniest video of a bird doing a “moon-walk.” Was that real or was it trick photography?

A You were seeing a video of a Red-capped Manakin, a small, plump, colorful bird of Central and South America, doing its courtship dance. The video, which was first aired on an episode of Nature, shows animal behaviorist Kimberly Bostwick in the field with three different species of manakins. Each of the species has developed unique and fascinating sound and visual displays, enhanced by specialized feathers and movements, designed to attract females and show off the male’s fitness.

Females select as mates the best dancers, which probably increases the likelihood that their young will carry the highest quality genes. Manakins make snaps, whistles, and other interesting sounds and jumps that are too fast for the human eye to follow, so Kim filmed them with high-speed video that captures the action at 500 frames per second, showing that the weird buzzes and clicks are produced not vocally but by the vibration of the birds’ wingtips, which can move faster than a hummingbird’s wings. The “moonwalking” Red-capped Manakins take a series of quick backward steps to achieve that Michael Jackson effect.

Is the behavior innate or learned? In most manakin species, two unrelated males form a partnership in which they sing and dance in a complex, coordinated pattern unique to their species, like the red-cap’s moonwalking. In a manakin partnership, one bird is dominant and gets to mate with the majority of females. The other bird is a sort of apprentice, apparently learning from the dominant male and perfecting his own display.

Q When I was walking my dog we came upon an injured Killdeer. At least it acted injured. I thought I should bring it to a rehabber, so I followed it, but suddenly it took off and flew away! One of my friends said Killdeer do that when they’re nesting. Was it really faking us out on purpose?

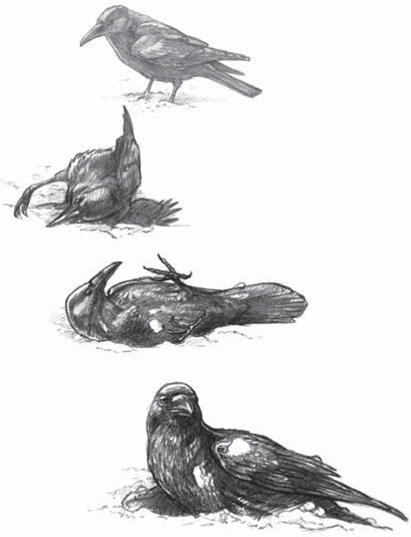

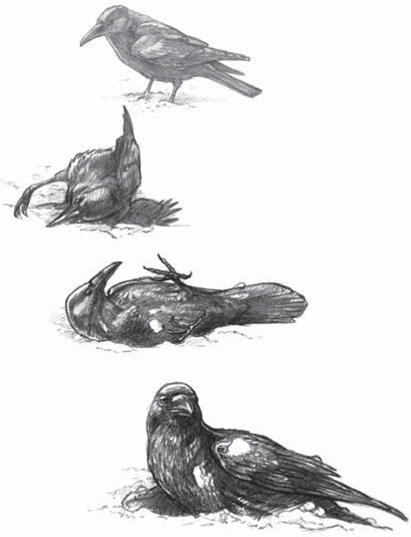

A Killdeer and several other species of birds, from Ostriches to songbirds, perform a distraction display when potential predators come near their eggs or chicks. Feigning injury with loud calls and drooping wings, the bird hobbles persistently away from the young, drawing a curious person or hopeful carnivore in a direction away from the nest. Killdeer seem to match the speed of the approaching animal, moving more slowly when leading people away than when leading dogs away.

Interestingly, Killdeer seem to modify this behavior for herbivores. A cow or bison is unlikely to eat a Killdeer egg but very well may trample it, and cattle are not likely to follow an injured bird regardless, so when a cow approaches a nesting Killdeer, the bird squawks and attacks it. There is even one report of a Killdeer posting itself directly in front of a nest, emitting a loud, high-pitched squawk, and parting a stampeding herd of bison.

Birds engaging in broken-wing distraction displays perform more intensely as the eggs grow closer to hatching and as the chicks get older; the behavior ebbs as the young learn to fly and are able to escape danger on their own.

Q My wife is a birder and when we went to Florida, she wanted to see a rare bird, the Florida Scrub-Jay. We went to a park where the birds are supposed to be and quickly spotted one perched at the top of a tree. She was about to take pictures but as she got her camera set up, a noisy group of people arrived. Instead of flying away, the bird flew right up to them and suddenly in flew five more scrub-jays! They actually landed on the hands of all these noisy people, taking peanuts that the people had brought to offer the birds! Are these birds endangered because they’re too friendly or curious for their own good?

A Florida Scrub-Jays are threatened because their habitat, sandy areas of Florida covered with native scrub vegetation such as palmettos and evergreen oaks, is being destroyed for citrus groves, housing projects, and shopping malls. These jays are adapted physically and behaviorally to this special habitat, which once covered much of central Florida and was maintained in low, open condition by frequent wildfire. Now at least 35 of the plant species in their scrub habitat are listed as endangered or threatened.

These jays are highly sedentary — the most successful ones never move far from their parents’ territory, staying within a total area of about one square mile their entire lives. When their territory is developed, the jays must disperse but cannot find a new territory because all the scrub around them is already occupied by territorial jays.

As human housing projects multiply, the remaining scrub grows tall and dense because of fire suppression management. These areas become unsuitable for the jays, and predators such as house cats have an easier time catching the young birds, so the local Florida Scrub-Jay population becomes extinct. This is happening in every region where this species exists.

Florida Scrub-Jays feed on a variety of arthropods, small vertebrates, berries, and acorns. Their jaw support and beak shape are specially adapted for opening acorns, which they can feed on year-round, even when acorns are not in season. During the fall acorn season, each jay stores thousands of acorns in the sand all around its territory. During the winter, when insects are scarce, they dig up and eat their stored acorns. They’re also known to land on the backs of deer, cattle, and feral hogs, to pull off ticks to eat.

They also frequently land on people who offer acorns, peanuts, or other food. The bird you and your wife found first was a sentinel, watching for predators and rival jay families. When the people arrived with peanuts, the bird probably alerted its family and they quickly appeared in hopes of a handout.

Q I spent a day at an ocean beach watching as Brown Pelicans dived straight into the water, dozens and dozens of times. I’ve been watching American White Pelicans for years without ever seeing them do that. Why do two birds that look so similar act so differently?

A American White Pelicans are specialized for feeding in freshwater, usually in shallow areas of lakes and rivers. If they tried diving into those waters, they’d kill themselves! Instead, they often group into little squadrons and fish cooperatively, forming a tight line and, by beating and dipping their wings and bills, herd fish into the shallowest waters where they can scoop them up.

Brown Pelicans, on the other hand, are marine birds, and although they, too, are extremely sociable and nest and loaf in large colonies, they don’t feed cooperatively. Instead, this species has perfected plunge diving. Brown Pelicans can see fish beneath the surface and can calculate where to dive, correcting for the refraction of light that makes fish appear in a different place than where they really are. During the dive, they pull their head in over their shoulders, pull their legs forward, and bend their wings at the wrist. Interestingly, they also rotate their body to the left, which probably protects their trachea and esophagus as they hit the water. These vital structures are situated on the right side of their neck.

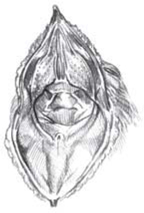

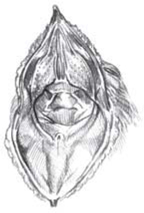

As their bill enters the water, the birds thrust their legs and wings backward, moving their bill toward the fish even faster. Their huge throat pouch expands as it fills with up to 2½ gallons (9.5 l) of water; the pressure forces the lower bill into a distorted bow shape but it doesn’t break, thanks to special muscle adaptations.

The streamlined upper mandible guides the fish into the mouth, the lower bill bounces back into shape, and the bird closes its bill, trapping the fish inside the pouch. It raises the back of its head slowly with the pouch pressed against its breast to drain out the water while retaining the fish, then tosses its head up to swallow the fish. If the dive was unsuccessful, the bird quickly raises its head with the bill open so the water drains out immediately. It takes less than 20 seconds to drain the pouch and swallow the fish.

Q Do birds play?

A Many mammals engage in “play,” that is, activities that enhance learning of motor and sensory skills and social behaviors but otherwise serve no immediate purpose. Young screech-owls pounce at leaves; young crows and jays pick up, inspect, and hide all kinds of shiny objects; young gulls and terns carry small items aloft and drop them, catch them in midair, and drop and catch them again. All these activities probably help birds acquire the skills and coordination they’ll need for hunting and other essential activities as adults.

Some forms of play, called “locomotor play,” seem quite similar to the exhilarating play of children sledding down a steep hill. Some ducks have been observed floating through tidal rapids or fast-moving sections of rivers, and when they’ve reached the end, hurrying back to the beginning to ride over and over. In the air, ravens and crows often rise on air currents only to swoop down toward earth, then glide back upward, again and again.

Common Ravens have been observed taking turns sliding down a snowbank on their tails or rolling over and over down a hill.

LEARNED VS. INSTINCTIVE BEHAVIOR

I receive many questions about learned vs. instinctive behavior. By “instinct,” people usually mean innate behaviors — those a bird does in a particular situation without learning or trying that behavior beforehand. Many innate behavior patterns are refined by learning.

For example, when a robin first hatches, it already knows how to do three things.

If something lands with a soft thud or jostles the nest, the little bird pops up like a jack-in-the-box with its mouth wide open to be fed.

If something lands with a soft thud or jostles the nest, the little bird pops up like a jack-in-the-box with its mouth wide open to be fed.

As soon as the little bird swallows, it backs up and poops.

As soon as the little bird swallows, it backs up and poops.

After it poops, it crouches down again and remains fairly motionless until the next time the nest is disturbed.

After it poops, it crouches down again and remains fairly motionless until the next time the nest is disturbed.

On a visit to the nest, the parent robins feed whichever nestling begs first, extends its neck highest, or holds its beak closest to the parent’s beak. Adults usually follow one or two flight patterns, alighting in the same spots over and over, so nestlings quickly learn, by feeding success, where to direct their beaks. They’re already refining their innate behavior by learning.

Learning Who’s Who and What’s What

For several days after hatching, robin nestlings beg if anything, including people or predators, alights on the nest or overshadows them. About five days after hatching, their eyes open and they start noticing their parents and one another. Once they recognize the birds that feed them, they will crouch down if anything else shows up. By the time they’re 10 or 11 days old, if anything approaches the nest they’ll fly off in a flurry, though they can’t go far and can’t get back up to the nest. (This is why it’s so important to not peek into robin nests after the young are about a week old.) If the young survive this sudden, panicky escape, their parents will continue to feed them and will try to lead them to dense vegetation to keep them hidden.

Robins don’t “imprint” on their parents or each other. For a day or two after leaving the nest, especially if something caused them to leave the nest too soon, a hungry robin chick who cannot find its parents may beg from other bird species or even people. I once saw a robin fledgling begging from my golden retriever! After a robin is flying well, it learns to follow its parents and associate with other robins. After that, it avoids other species.

Robins have a few sharp warning calls, including a high-pitched seeee made when a hawk flies overhead, and peek and tut-tut calls when danger is lower to the ground. Young birds recognize the sounds their parents make and act on these sounds; some of this may be innate and some refined by learning as they notice what their parents do.

Both parents attend to the young after they leave the nest. After the female produces a new clutch, she incubates them as the father stays with the fledglings. Every night he flies to a communal robin roost, and they follow. He will start focusing on his new nestlings after they hatch; by then the fledglings will be independent.

Scratching and Flying

As its feathers start to grow, a young robin scratches with its beak and claws, an innate behavior that is clumsy at first. The bird quickly improves its technique by learning what movements are most comfortable and effective. The young bird innately flaps its wings, and the combination of feather growth, developing muscles, and learning refines those initial awkward efforts into skillful flying.

Making More Robins

Robins are drawn to other robins in big, loose flocks. They stay safe and discover new food sources thanks to the many eyes and ears of the group, until rising hormone levels in spring induce territorial and breeding behaviors. These behaviors are innate but are also refined by the responses the robin gets and how successful each behavior is. Singing robins refine their songs and add phrases unique to the neighborhood they nest in, even though they may have been raised far from there.

When robins lose their young, they move to a new site to re-nest, and sometimes a pair breaks up. If they successfully raise a brood, the same pair will often re-nest two or even three times that season. Although robin pairs work together in raising their young, their bond isn’t quite what romanticists might like. In one study, “extra-pair paternity” occurred in almost 72 percent of all broods. In each of these “EPP” nests, at least one chick wasn’t fathered by the male taking care of it. According to that study, females may be allocating paternity based on their assessment of each male’s parental performance. Females invest a great deal into their eggs, and multiple fathers hedge their bets.

If a mate is killed, sometimes another male will take over rearing the chicks. In my own backyard, a Cooper’s Hawk once killed the male robin nesting in my hedge. The next day, the female had accepted a new mate who helped her feed her nestlings. I wondered if he was the genetic father of one or more of the nestlings, but he apparently never insisted on a paternity test.

Species Specific

Q I am curious about the Turkey Vultures that roost in the tall pine trees a block from our house, right near a cemetery — there is even a sign on the road that says “Dead End”! I never thought of vultures as particularly social — what are their mating and nesting habits?

A Turkey Vultures usually forage individually. By splitting up, each bird sniffing out carcasses, one is eventually going to hit the jackpot and others will notice it dropping down and will join it. In the evening, vultures join together at communal roosts, ranging in size from a few birds to several thousand. Spectacular evening flights “advertise” these roosts.

One 15-year study of tagged Turkey Vultures in Wisconsin suggests that they usually mate for life, but when a bird’s mate dies, it does take a new mate. Although they spend the nesting period together and cooperate closely in incubating eggs and caring for the young, there’s no evidence that a pair migrates or spends winter together.

Turkey Vultures nest on cliffs, hollows beneath fallen logs, rock outcrops, caves, abandoned buildings, and other places isolated from humans. They don’t construct much of anything in the way of a nest for their (usually) two eggs. Both parents develop brood patches, a bare spot on their underside that is pressed against the eggs. Both take turns incubating the eggs, which take over a month (often as long as 40 days) to hatch.

The parents feed their fluffy white chicks the same rotten meat they eat, only in regurgitated form. The chicks make their first flights sometime between 60 and 80 days after hatching. After they leave the nest, they receive little or no care from their parents, but siblings sometimes stay together for a while. They join communal roosts, keep track of other birds in order to locate food as they get practice sniffing out the world, but are generally on their own.

AS SILENT AS THE GRAVE

Turkey Vultures lack a syrinx and the voice-producing muscles associated with it, so they are essentially always silent. They can make a guttural hiss when agitated, either by a disturbance at the nest or when two birds are vying for the same part of a carcass. And nestlings make a characteristic hiss that is almost inaudible while they’re still blind and unable to hold up their heads. By the time they’re a week old or so, they make a specific nestling-hiss when disturbed. This sound has been variously described as a persistent and vigorous wheezing-snoring; a low, throaty, or growling hiss; a snake rattle; or a roaring wind. The sound volume and quality depend on the age of the nestling, the intensity of the hiss, how close the observer is, and the acoustic qualities of the nest area. The sound is often given by both nestlings at once. If disturbed, nestlings can also stomp their feet or loudly flap their wings.

Turkey Vultures lack a syrinx and the voice-producing muscles associated with it, so they are essentially always silent. They can make a guttural hiss when agitated, either by a disturbance at the nest or when two birds are vying for the same part of a carcass. And nestlings make a characteristic hiss that is almost inaudible while they’re still blind and unable to hold up their heads. By the time they’re a week old or so, they make a specific nestling-hiss when disturbed. This sound has been variously described as a persistent and vigorous wheezing-snoring; a low, throaty, or growling hiss; a snake rattle; or a roaring wind. The sound volume and quality depend on the age of the nestling, the intensity of the hiss, how close the observer is, and the acoustic qualities of the nest area. The sound is often given by both nestlings at once. If disturbed, nestlings can also stomp their feet or loudly flap their wings.

Scientists are still trying to tease out the relationship of American vultures to hawks and to storks. Traditionally, vultures have been classified with hawks, based on many features and their need for meat. But in the 1990s, they were placed in the same order as storks based on many similar features, such as bald heads, perforated nostrils, and a curious habit of urinating on their legs to cool off. Then thanks to reanalysis of DNA, they were placed closer to hawks again.

Regardless of where they really belong, it’s appealing to consider the similarities of storks, the birds that most symbolize birth, with vultures, the birds that most symbolize death. And it’s also interesting to note that vultures, as well as crows and ravens, seem to avoid scavenging the carcasses of other large black birds.

Q I often see a crowd of Cedar Waxwings and/or robins on my crabapple trees in the late winter, but once I saw two pairs of Pine Grosbeaks. They stayed for about 20 minutes, eating the fruit and bathing in an icy puddle in the yard. What is their usual habitat and might I see them again here in western Massachusetts?

A Pine Grosbeaks are members of the finch family, along with goldfinches, redpolls, siskins, Purple and House finches, crossbills, and Evening Grosbeaks. They breed in subarctic and boreal forests in Asia, Europe, and, in North America, from eastern Canada to western Alaska. They also breed in coniferous forests of western mountain ranges and in coastal and island rain forests of Alaska and British Columbia. Like other northern finches, Pine Grosbeak migrations are unpredictable. But they move southward less often than, and don’t go as far south as, many other “winter finches.”

They aren’t particularly drawn to robins or waxwings but are attracted to mountain ash and crabapple, and so are often found feeding with them in winter. Male and female Pine Grosbeaks are very territorial during the breeding season — both will fight off members of their own sex that invade their territory. But after the young fledge, Pine Grosbeaks become gregarious and associate in flocks. It’s possible that their winter flocks are composed of family members. As I noted, they come south occasionally but not predictably. When they appear in Massachusetts, it’s something to treasure.

A MAGIC MOMENT

The very first Pine Grosbeak I ever saw was a young male separated from his flock. I heard him before I saw him and whistled back to him when I was still more than a block away. I walked toward the sound of his whistle, continuing to answer his persistent whistles with as good an imitation as I could muster. Soon I saw him at the top of a tree, looking right at me when I whistled. I have no idea what prompted me on a frozen February day, but I took off my glove and raised my hand, and he lighted right on my finger! He looked at me and whistled, I whistled back, and he gave me one last whistle before flitting back into the trees.

The very first Pine Grosbeak I ever saw was a young male separated from his flock. I heard him before I saw him and whistled back to him when I was still more than a block away. I walked toward the sound of his whistle, continuing to answer his persistent whistles with as good an imitation as I could muster. Soon I saw him at the top of a tree, looking right at me when I whistled. I have no idea what prompted me on a frozen February day, but I took off my glove and raised my hand, and he lighted right on my finger! He looked at me and whistled, I whistled back, and he gave me one last whistle before flitting back into the trees.

It was one of the most thrilling moments of my life. But it may well have been one of the most disappointing for the grosbeak. I think my whistling back to him must have given him hope that he’d found another grosbeak flock, but all he found was a clumsy, flightless human.

Q Why are Saw-whet Owls so small?

A Bird size is determined by a combination of things. One of our largest owls is the Great Gray Owl, which specializes on pretty much the same size food that Northern Saw-whet Owls eat — very small rodents. The Great Gray Owl takes advantage of its huge ears to hear meadow voles when they are buried under deep snow or meadow grass; it flies in and plunges to grab the vole, then uses its huge wings to pull back out. The problem with having such a large body is that it must catch a lot of mice to survive.

Northern Saw-whet Owls are too tiny to hunt where snow or grass is so deep, but they live in forests where snow isn’t as deep, especially around tree trunks, so although they don’t eat as many mice as Great Gray Owls do, they can find enough to keep their tiny bodies alive.

Their size makes them very maneuverable in flight, and they can also obtain a good amount of the nutrition they require from large insects in summer. In addition, Northern Saw-whet Owls are small enough to take shelter in woodpecker holes, which Great Gray Owls certainly can’t do!

Bird feathers insulate the bird, protecting it from too much heat and cold, but they can also hold an incubating bird’s heat away from its eggs. So at the time eggs are laid, belly feathers on most female birds, and the males in some species, become loose. The parents pluck them out, often to use as part of their nest lining, so they can press their warm abdominal skin directly on the eggs to heat them.

Q I live 150 miles from the coast. Why do we have seagulls flying around a local strip mall parking lot? I see them all the time.

A The term seagull is technically correct only when referring to Jonathan Livingston or to a gull that happens to be on the ocean, but it’s widely used as a generic term for gulls in general. A great many gulls spend their lives inland. The one that usually frequents fast food restaurants and strip mall parking lots is the Ring-billed Gull. It feeds on slugs, worms, and other invertebrates found on lawns, scavenges on garbage, and mooches from people. I’ve watched Ring-billed Gulls pluck warblers out of the air first thing in the morning when the exhausted, tiny songbirds are coming down after a night’s migration. They also feed on fish. Their mouths are very wide, and their throat and esophagus expand to swallow an entire small fish.

Birds that are specialized may be limited in food choices by their own bodies. But even generalists are limited in their food choices. Blue Jays are omnivorous, and during the course of their lifetime travels, they encounter many unfamiliar food items. Some berries and insects that seem perfectly fine may actually be toxic.

Birds that are specialized may be limited in food choices by their own bodies. But even generalists are limited in their food choices. Blue Jays are omnivorous, and during the course of their lifetime travels, they encounter many unfamiliar food items. Some berries and insects that seem perfectly fine may actually be toxic.

In the wild, jays and crows can recollect when, where, and what food they’ve stored.

In the wild, jays and crows can recollect when, where, and what food they’ve stored.